-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Shaun Colburn, David G. Benditt, Age at first syncope: a consideration for assessing probable cause?, European Heart Journal, Volume 43, Issue 22, 7 June 2022, Pages 2124–2126, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehac122

Close - Share Icon Share

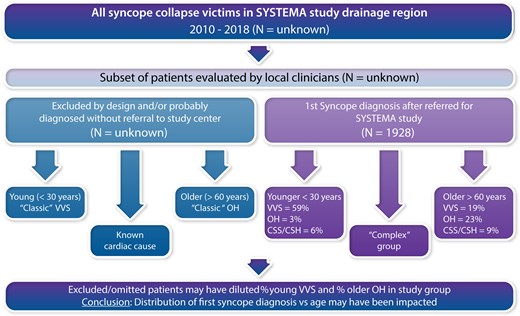

Illustration depicting how patient selection may bias findings. It may reasonably be assumed that only a portion of all syncope/collapse patients are evaluated and from that subset of all patients many were excluded from the study (Left) for various reasons. These excluded patients (e.g., classic VVS or OH cases) would impact the subset of the overall patient population evaluated for first syncope (Right) and inevitably the conclusion that age at first syncope may be a helpful diagnostic tool (see subsection entitled Limitations in this Editorial).

This editorial refers to ‘Early- and late-onset syncope: insight into mechanisms’, by P. Torabi et al., https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehac017.

In this issue of the European Heart Journal, Torabi et al. examine how apparent causes of suspected first syncope events change as the population ages.1 The findings are derived from a database [SYSTEMA (Syncope Study of Unselected Population in Malmo), Lund University, Malmo, Sweden)2,3 based on diagnostic evaluation of referred syncope/collapse patients undertaken over an ∼10-year period.

Main findings

The authors provide two key findings. First, they observed a bimodal distribution of syncope occurrences with increasing age; an initial peak occurred at late adolescence, and a second at approximately age >60 years. Second, excluding patients with established cardiac syncope, the identified causes of syncope in the study population differed with patient age. Vasovagal syncope (VVS) was most common when first symptoms presented at a young age; orthostatic hypotension (OH) or carotid sinus syndrome/hypersensitivity (CSS/CSH) became more prevalent when first syncope events occurred in older patients.

In terms of syncope as a function of age, as Torabi et al. acknowledge,1 the distribution of first syncope events has been reported previously to be bimodal, with peaks at ∼15 years of age and another around age 70 years;4,5 further, the bimodal nature of the distribution would probably be accentuated if cardiac syncope causes were included in the analysis, as cardiac causes inevitably become more common as the population ages. On the other hand, existing reports supporting a bimodal distribution are relatively weak, having been based on small or ill-defined populations. The SYSTEMA study,1 given its large size and investigator expertise, provides stronger evidence for such a distribution, with VVS, not unexpectedly, being the predominant driver in the younger individuals. In this regard, to be fair, the patient population studied did not include young patients with known congenital structural heart disease or identified channelopathy. The absence of such individuals would be expected to enrich the VVS contribution in the younger age group. Thus, without a full complement of patient diagnoses in the population, age cannot be used alone as a confident diagnostic instrument.

Understanding the cause of first syncope events as provided in the current report by Torabi and colleagues1 is of more than academic interest given the potential impact of syncope on subsequent mortality risk, need for device implantation in certain cases, and overall quality of life. By way of example, the Danish National Patient register database comprising >37 000 syncope patients and 185 000 controls6 indicates that first syncope events, even in seemingly healthy individuals, are associated with increased mortality risk. All-cause mortality was significantly greater in those with syncope [8.2% vs. 7.1%; hazard ratio (HR) 1.06; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.02–1.10]. Recurrent syncope, cardiac event hospitalization, stroke, and cardiac device implantation were also more frequent. Notably, and somewhat surprisingly, the increased mortality risk was particularly evident in a middle-aged cohort (26–44 years of age; HR 2.29, 95% CI 1.87–2.80, P < 0.0001 vs. controls).

In brief, the current SYSTEMA database observations1 not only tend to be supportive of prior reports with regard to the age distribution and nature of first syncope events, but also provide substantially greater numerical granularity; consequently, these findings contribute to better understanding of the causes of syncope in various age groups.

Limitations

Certain cautions need to be considered in interpreting the current SYSTEMA observations; a number of these are summarized here.

First, it is important to understand the nature of the SYSTEMA population, specifically in this case the 1972 patients who underwent head-up tilt testing (HUT) between 2008 and 2018. SYSTEMA was designed to evaluate patients referred to an expert centre for further assessment of unexplained syncope/collapse.2 By 2020, >2100 patients had been enrolled.7 The authors indicate that patients with known cardiac syncope or non-syncope collapse were excluded.

The basis for patient referral provides an important potential opportunity for interpretive bias since it may be reasonable to conclude that individuals with a presumed firm diagnosis at the primary care level would not be referred. For instance, one might anticipate that compared with older syncope patients, younger VVS patients who present with a full complement of symptoms derived from robust autonomic activation may be readily diagnosed at the primary care level; these individuals would not typically require diagnostic referral (although help with preventive treatment may still be needed). Conversely, fewer older patients have or report prodromal symptoms (in this study 26% in the older group vs. 64% in the younger group). Thus, there may be a tendency for older VVS patients to be more likely to be sent for higher level diagnostic assessment. The net effect would be inadvertent enrichment of the overall population with older VVS patients at the expense of the younger group. Consequently, the study population in the current report may not be truly ‘unselected’; optimally, the epidemiological conclusions would necessarily need to incorporate those individuals who for one reason or another were omitted from the current study population. The latter may not be possible at this stage, but the uncertainty indicates that only by beginning recruitment at the primary care level can a full appreciation of syncope epidemiology be achieved.

A second difficulty with interpretation of the current results arises by virtue of use of the term ‘syncope’ itself. By consensus definition,8,9 syncope implies transient loss of consciousness (TLOC) due to temporary inadequacy of cerebral oxygenation (most commonly the result of a hypotensive event). Consequently, in evaluating the epidemiology of ‘true’ syncope, patients with collapse of other causes (e.g. seizures or concussions) must be excluded. As noted earlier, the authors indicate that patients with known cardiac syncope or non-syncope collapse were excluded. However, for most readers, this step is not straightforward. In fact, the latter step may be a substantial challenge even in the setting of a tertiary referral centre given the often considerable temporal discontinuity between the event in question and the initiation of expert evaluation. As time passes, eyewitness reports tend to become second hand (or lost entirely), and the victim’s memory of warning symptoms may become murky, especially in older individuals in whom, apart from retrograde amnesia, cognitive dysfunction is a frequent comorbidity.10–13 In such circumstances, conventional diagnostic tools are inevitably of diminished value. It would be useful to have an estimate of how long patients waited before evaluation, and how many referred patients were removed from consideration due to uncertainty regarding the initial diagnosis being ‘true syncope’. The authors allude to this problem briefly in discussion of the patient population and in the limitations, but the impact on interpretation of the findings is unstated.

A third consideration is the precision with which patients are able to recall details of remote events. The authors raise this issue in the limitations section, and it is important. As noted above, previous studies indicate that retrograde amnesia is a common accompaniment of true syncope especially in older individuals (not to speak of any effects of possible concomitant head injury that may be associated with a collapse event).12,13 While comorbidities are detailed extensively in their table 2, the occurrence of head injury either recently or in the past is unaddressed.

A further issue among the interpretation concerns is that reliance on laboratory observations may be misleading, particularly if not established by symptom reproduction. By way of an example, the authors correctly point out that the reproduction of symptoms was an essential component of their differentiating CSS from CSH. However, it is unclear whether CSH alone was ever considered an adequate diagnostic endpoint. An analogous dilemma arises in the interpretation of ‘complex syncope’ in which abnormalities may have been identified, but symptoms not reproduced. Additionally, the authors point to the importance of HUT as both a reason for referral as well as a basis for making a diagnosis of VVS. However, in most cases (especially in younger patients), it is the history and eyewitness accounts that best establish the VVS diagnosis.

An additional diagnostic dilemma is raised by the designation ‘complex syncope’. This is a novel diagnostic category that to our knowledge is not widely employed and which the authors themselves have not used previously; nonetheless, it accounted for ∼30% of diagnoses in patients across all age groups. In this report, ‘complex syncope’ was defined as detection of two or more possible causes for syncope in a given individual; the result was that a definite single diagnosis could not be offered. Such a situation is a common problem, especially in older patients, thereby necessitating judgement by the experienced attending physician (a skill that has been acknowledged to be quite valuable in prior reports), along with a careful conversation outlining the diagnostic uncertainty with the patient and family. Thus, for example, the presence of both CSS/CSH and OH in an older person is a common finding. In such cases, the specific diagnosis may come down to historical details and witness accounts. Similarly, conduction system disorders and cardiac autonomic disorders are often observed in patients suffering from various neurological diseases (e.g. synucleinopathies, myotonic dystrophy, or Parkinson’s disease); such combinations may be associated with serious cardiac arrhythmias as well as chronotropic incompetence and increased OH susceptibility.14,15 It is not clear how one should adjudicate such cases; perhaps simply stating that the diagnosis is ‘indeterminate’ would be best.

Apart from the uncertainty raised by introducing the ‘complex’ syncope concept, it raises the confounding issue of whether, for a given individual, a single diagnosis is either appropriate or adequate over a lifetime. We think that the authors would agree that even though, for example, if VVS is considered to have been the problem at one point in time, one cannot safely rely on subsequent events being due to the same cause. The importance of determining and addressing a specific diagnosis for each event was highlighted by Ruwald et al. 16 These investigators found that over a wide age range (15–39, 40–59, and 60–89 years) recurrent syncope was associated with an approximate two- to three-fold increased all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality. It is unlikely that recurrent VVS was at fault as time passed. Perhaps the initial diagnosis was wrong. Alternatively, and more likely, as time passes the cause(s) of subsequent events change. In essence, careful assessment is needed to establish a specific diagnosis for each syncope presentation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the SYSTEMA study investigators provide important insights furthering understanding of the epidemiology of syncope/collapse across age groups. The large size of the study population, and the consistent approach to diagnosis by acknowledged experts, are particular strengths. Not unexpectedly, however, increased understanding inevitably raises additional issues that merit consideration. We have endeavoured to highlight certain of these issues here, with the hope that they will provide a source of inspiration for future study.

Funding

D.G.B. has been supported by a grant from the Dr Earl E. Bakken family in support of heart–brain research.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

Author notes

The opinions expressed in this article are not necessarily those of the Editors of the European Heart Journal or of the European Society of Cardiology.