-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Martin Halle, Melanie Heitkamp, Prevention of cardiovascular disease: does ‘every step counts’ apply for occupational work?, European Heart Journal, Volume 42, Issue 15, 14 April 2021, Pages 1512–1515, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab105

Close - Share Icon Share

This editorial refers to ‘The physical activity paradox in cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: the contemporary Copenhagen General Population Study with 104 046 adults’†, by A. Holtermann et al., on page 1499.

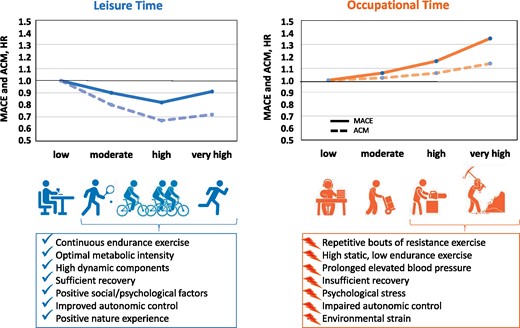

Leisure time physical activity and occupational physical activity in relation to major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and all-cause mortality (ACM). Cox regression models were adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, smoking, years in school, diabetes, systolic blood pressure, blood pressure medication, dietary preferences, alcohol consumption, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) stage, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol and triglycerides, resting heart rate, vital exhaustion score, occupation, cohabitation, marital status, and household income.1 The potential role of preventive factors of leisure activity and negative factors increasing risk. HR, hazard ratio.

In this issue of the European Heart Journal, Holtermann and colleagues from Denmark report interesting data from the Copenhagen General Population Study, a large national cohort of 104 046 adults including national health registry data with baseline measurements in 2003–2014 and a median follow-up of 10 years, adjusting for several important confounders such as socioeconomic status, lifestyle, and living conditions.1 They confirmed their previous hypothesis that self-reported physical activity performed during leisure time is associated with reduced major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) as well as all-cause mortality, whereas occupational physical activity is associated with an increased risk. This relationship has previously been termed the ‘physical activity paradox’.2 , 3

Compared with low leisure time physical activity, data analysis revealed a significant risk reduction for MACE for leisure time physical activity when performed at moderate, high, or very high volume (intensity × duration) of 10, 18, and 9%, respectively.1 In contrast, those groups reporting a high or very high volume of occupational physical activity revealed a significantly increased risk of MACE of 16% and 35%, respectively. Importantly, the two physical activity domains were revealed to be independent risk predictors. Higher levels of leisure time physical activity had a clear protective effect in those who had reported a sedentary job. Instead, leisure time activity had no benefit in those with high or very high levels of occupational activity, which underlines the independently increased health risk for blue collar workers, involved in heavy manual work.1

Evidence from history: physical activity at work reduces cardiovascular risk

Almost 70 years ago, Jeremiah Noah (‘Jerry’) Morris and his colleagues published a landmark study in The Lancet in 1953, which launched a new era of research recognizing the role of physical activity in the prevention of heart disease and its impact on public health overall. Morris et al. conducted a large survey of 31 000 employees aged 35–65 years from the London Transport Executive, e.g. drivers and conductors of trams and trolleybuses, and driver and guards on the underground railways, and observed that men in physically active jobs had a lower incidence of coronary (ischaemic) heart disease than men in physically inactive jobs.4 Specifically they observed that drivers, who mainly sit during their work, were at an almost two-fold higher risk of first lethal ischaemic cardiac event compared with their conductor peers, who constantly climb the stairs and walk through the aisles of double-decker buses. The authors concluded that physically active jobs are protective for heart disease, acknowledging, however, other factors that may also have influenced this association, e.g. physical disabilities or underlying coronary heart disease, as reasons to change from a heavy to a light, more sedentary occupation.4

Since that time, evidence from numerous populations and continents has broadly and consistently shown that regular physical activity has extensive beneficial effects on cardiovascular health and premature mortality, a scientific finding which has been widely implemented in recommendations of the World Health Organization as well as guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology.5 , 6

‘Every step counts’ as a key factor for cardiovascular prevention?

Beyond the role of regular physical activity in cardiovascular health, even higher levels of total physical activity well beyond the current recommendations are associated with substantially reduced morbidity and mortality.7 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis including 48 prospective cohort studies has shown that compared with the recommended ‘volume’ of physical activity [750 metabolic equivalent of task (MET) min/week; equivalent to 3 h of brisk walking per week], mortality risk was even lower for physical activity levels exceeding the recommendations, for all-cause mortality by 14% and cardiovascular mortality by 27%. Moreover, even weekly vigorous physical activity of 10–12 h had no negative effect on survival.7

Accordingly, current guidelines recommend physical activity in any form and do not distinguish between different domains, e.g. physical activity conducted during leisure time, household, or occupational time.5 This evidence is supported by cohort analyses from different countries with a broad range of socioeconomic differences as performed in the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study (>130 000 participants without pre-existing cardiovascular disease). Questionnaires assessing physical activity revealed that compared with low physical activity (<600 MET min/week or <150 min/week of moderate intensity physical activity), moderate (600–3000 MET min/week or 150–750 min/week) and high physical activity (>3000 MET min/week or >750 min/week) were associated with a graded reduction in mortality (hazard ratio 0.80 and 0.65; P < 0.0001) and major cardiovascular disease (0.86 and 0.75; P < 0.001). Although, in general, physical activity in high-income countries is mainly recreational, whereas in lower income countries it is mainly non-recreational, the PURE data show that overall higher physical activity is associated with lower risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality irrespective of the socioeconomic status.8

Evidence for a physical activity paradox?

These global data seem contradictory to the current findings by Holtermann et al. Support comes from another Scandinavian cohort study from Norway assessing 17 697 men and women with a mean age of 47.2 years examined in 1987–1988 and followed for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality for 26 years. This analysis also showed a U-shaped relationship between occupational physical activity and mortality.9 Compared with the ‘moderate’ group characterized by walking or lifting tasks as part of their occupation, a 16% higher all-cause mortality was observed in the sedentary and a 13% higher all-cause mortality in those with heavy manual jobs.9 The equivocal constellation is reflected by a recent umbrella review on the influence of occupational physical activity on health, which highlighted the heterogeneous evidence concerning this topic.10

Importantly, evidence for most of the physical activity data including the Copenhagen General Population Study is generated by observational cohort studies. As also stated by Holtermann et al., these studies are limited by unknown confounding, selection bias, and information bias, and do not allow for excluding reverse causality.1 Moreover, leisure time and occupational physical activity were rather crudely assessed by four categories. Furthermore, cardiorespiratory fitness as an important predictor of mortality9 was not assessed but adjusted for resting heart rate at baseline only, which is a relatively weak indicator of physical fitness. It should also be underlined that, in the current study, the very high occupational physical activity group had a higher prevalence of current smokers, greater body mass index ≥30 kg/m2, lower level of education, and a higher weekly alcohol consumption compared with the group with low occupational physical activity.1 Unexpectedly, for those with heavy manual jobs, they also report a high prevalence of very high leisure time physical activity and high adherence to dietary guidelines. This overall indicates the important limitations of self-reported data on lifestyle, which are often affected by misclassification due to social desirability or recall bias, often resulting in overestimation of physical activity.11 Nonetheless, the large cohort and the methodological strengths of the Copenhagen General Population Study make an important and significant contribution to the cardiovascular and overall risk of occupational work, which has to be followed and differentiated in future studies.

Explanation for a physical activity paradox

Physical exercise performed during leisure or work time is different in character as leisure time exercise comprises more aerobic endurance exercise whereas occupational exercise primarily involves repetitive resistance exercise of short bouts and often insufficient recovery time.12 Moreover, workers in heavy manual jobs may be particularly exposed to psychological factors (e.g. night shifts and environmental stressors such as noise or air pollution), which are less frequent in sedentary jobs (e.g. office work)12 (Graphical Abstract). These stress factors may clearly affect the relationship between physical work as part of an occupation and cardiovascular risk factors, e.g. arterial hypertension, increased inflammation, vascular dysfunction, atherosclerosis, and cardiovascular events.13 , 14 These factors may also be responsible for excess overall mortality in this group.

What are the consequences for science and occupational health?

For science

To identify and clearly define high-risk group workers, precisely defining occupational tasks and assessing specific psychological and environmental stressors.

To conduct randomized controlled trails focusing on the high-risk group including tailored interventions to target specific risks in relation to occupational stressors and considering cardiorespiratory fitness as an intermediate and cardiovascular events as a clinical endpoint.

For occupational health

Companies should offer breaks and recovery time during work, sufficient recreational breaks, and complementary exercise training for their employees, especially for workers in heavy manual jobs.

Occupational health management strategies, e.g. addressing normal weight, low alcohol consumption, and smoking cessation, should be implemented, evaluated, and improved, targeting high-risk workers in particular.

Healthcare professionals should assess and address the particularly elevated risk of heavy work occupations and emphasize a healthy lifestyle in these high-risk patients at an early stage.

Acknowledgements

We thank Pascale Heim-Ohmayer BSc, Technical University of Munich, for her support and scientific input.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

The opinions expressed in this article are not necessarily those of the Editors of the European Heart Journal or of the European Society of Cardiology.

Footnotes

† doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehab087.

References