-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Annabelle Page, Music and love in Sigismondo Fanti’s Triompho di Fortuna (1527), Early Music, Volume 51, Issue 1, February 2023, Pages 69–90, https://doi.org/10.1093/em/caac068

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

As he explains at great length in his introduction, Sigismondo Fanti painstakingly calculated and constructed his Triompho di Fortuna with the purpose of enlightening its reader as to their fortunes following on from a given situation in their life. Every step along the somewhat convoluted journey towards discovering one’s fortune is accompanied by richly meaningful imagery. The illustrations not only, in some cases, summarize the text, but also make persistent connections between the playing of the game and broader intellectual, military and artistic culture.

Music appears in multiple visual forms throughout the book. Some of the ‘Wheels’ forming part of the journey through the game are given musical characters (‘Wheel of Music’, ‘Wheel of the Lyre’). A very large cycle of portraits appearing alongside some segments of the game includes musicians ranging from mythological figures to Fanti’s contemporaries. And among the tiny woodcut scenes that accompany and characterize the various fortunes at the end of the book are several musical scenes. A substantial proportion of the questions and answers provided by the book concern love, and it is with fortunes concerned with love that musical scenes are most often associated, shading across the topics of sex, romance, decorum and faithfulness.

In this article—the first to expose Fanti’s the Triompho di Fortuna as a rich, multidisciplinary source—the connections proposed in the book between different aspects of love and their musical characterization will be discussed and contextualized.

As he explains at length in the introduction to his Triompho di Fortuna (Venice, 1526), Sigismondo Fanti painstakingly calculated and constructed his remarkable fortune-telling game to enlighten its readers as to their futures, following on from a given situation in their life. Every step along the somewhat convoluted journey towards discovering one’s fortune is accompanied by richly meaningful imagery. The illustrations not only, in some cases, summarize the text, but also make persistent connections between the playing of the game and broader intellectual, military and artistic culture. Fanti’s Triompho belongs within a larger corpus of games, gaming books and verbal entertainment devices that were enjoyed in the salons of early modern Italy. The references to a shared contemporary culture aided connection between party guests. The likes of Straparola’s Lucrezia and Castiglione’s Emilia could thus become mistresses of veglie, the convivial gatherings at which, in some cases, women could interact with and among male guests as equals.1 Such social contexts provided fertile ground for discussions of particular topics: love, gender and sexuality.

Music appears in multiple visual forms throughout the book. Some of the Rote or ‘Wheels’, the game’s interactive element, are given musical characters (‘Wheel of Music’, ‘Wheel of the Lyre’). A substantial cycle of portraits accompanying the Sphere (Spheres) section includes musicians ranging from mythological figures to Fanti’s contemporaries. And among the Figure, the tiny woodcuts that accompany and characterize the various fortunes at the end of the book, are several musical scenes. A substantial proportion of the questions and answers provided by the book concern love, and it is with fortunes concerned with love that musical scenes are most often associated—shading across the topics of sex, romance, decorum and faithfulness. These repeated connections between love and the musical images illustrate the versatile role given to music in 16th-century Italian visual culture, with its ability to evoke real-life ideas and scenarios, both virtuous and illicit.

This article—the first to expose the musical treasures of the Triompho di Fortuna, as a rich, multidisciplinary source—focuses on the discussion and contextualization of the different aspects of love and their musical characterization in Fanti’s text. I first situate the Triompho within its historical context, before discussing the structure of the book and identifying its musical references. I then go on to spotlight the music-and-love-related Figure by describing a series of ‘play-throughs’, designed to exemplify an imagined player’s experience of the musical references in the book, whilst at the same time proffering an analysis of its themes.

Fanti and the Triompho di Fortuna

Fanti’s Triompho is a curious fortune-telling game in book form, printed in Venice by Agostino Zani at the instigation of Jacomo Giunta in January 1527, under both papal and Venetian privileges.2 An enormous volume, running to nearly 300 folio-sized pages, the Triompho’s graphic design and extensive suite of woodcut illustrations are yet to be conclusively attributed; some have argued for the involvement of Ferrarese Dosso Dossi, and perhaps a team of other, less-experienced local artists. The elaborate frontispiece (based on a pen drawing held at the picture gallery of Christ Church, Oxford) has been attributed to Baldassare Peruzzi.3 The book is dedicated to Pope Clement VII, who is represented on the frontispiece perched perilously atop a globe rocked by contrary fortunes, caught in a moment of choice between virtue and physical pleasure (illus.1).4 This striking image evidently connects with the circumstances of the Italian Wars of the 1520s, during which Clement’s weak leadership (in the opinion of many contemporaries) directly contributed to the disastrous Sack of Rome in 1527.

![Sigismondo Fanti, Triompho di Fortuna (Venice, 1527), frontispiece, sig.[aa]r (all images from the Triompho in this and succeeding illustrations are Public Domain, taken from the digitized copy in the Lessing J. Rosenwald collection, Library of Congress, Washington DC, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, call no. gv1302.f3; see https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.rbc/Rosenwald.0817)](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/em/51/1/10.1093_em_caac068/1/m_caac068_fig1.jpeg?Expires=1747881849&Signature=TYKie9mfPQU4bDLLygzBHK0E5djpvw9MmEOfYrwzQihWrP8jLcD35uSfwF~3pea2BuHtfb2GM3nNL5HI~EW5dFy5Fg0MbOGhx-lyhxwfBdpt6evGXt5lSomiU8PTvSaT~WllxbmyyfT~5WNnuzuKNFQGn9zTASbQBpgD4jMQ64H4ycH-5uE5OxMbOB2P998-uB7aHFYFQYqazo1sC-yUw8JqfHhCSm2nnh-O0R38p2P0QU-Sy15l9LgKn9EuBq3NMULZLZzLMharooUK9pXSpPEEXbw5qVk5yssr4DD2XIrL6mM0zD4m5uDmJdD3W2EJTgelzJBjKOcJ4lDpIiLAJg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Sigismondo Fanti, Triompho di Fortuna (Venice, 1527), frontispiece, sig.[aa]r (all images from the Triompho in this and succeeding illustrations are Public Domain, taken from the digitized copy in the Lessing J. Rosenwald collection, Library of Congress, Washington DC, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, call no. gv1302.f3; see https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.rbc/Rosenwald.0817)

Fanti himself is a rather enigmatic figure. A native of Ferrara, it is clear from numerous features of the Triompho that he was closely familiar with the Este court and felt motivated to celebrate it. Indeed, a letter of 1521 published by Albano Biondi indicates that he owed allegiance to Duke Alfonso I d’Este at that time.5 Exactly what was his role at court is a little difficult to determine because Fanti is, himself, his main biographer, and he makes what are self-evidently exaggerated claims regarding his qualifications and professional competencies. However, his principal career appears to have been as a soldier and military engineer, a capacity in which he was serving in Venice at the time of the 1521 letter, and in which the government of Venice again secured his services in 1526, according to Marino Sanudo.6 If Fanti’s scholarly pursuits were amateur, they were nonetheless impressive and extensive. In 1514 he published a high-minded vernacular handwriting manual entitled Theorica et practica … de modo scribendi fabricandique omnes litterarum species, dedicated to Alfonso d’Este, which analyses letter shapes using geometrical principles. It enjoyed several reprints and inspired numerous imitators. In the preface to that work Fanti claims authorship of a long list of further treatises on geometrical and astrological topics, which apparently have not survived. Overall, Fanti’s scholarly focus was clearly Quadrivial, and in that respect his engineering pursuits were of a kind with his other interests. His earliest biographer, the Ferrarese historian Marco Antonio Guarini, called him a Matematico perfettissimo (very perfect mathematician).7

The Renaissance fashion for astrology centred predominantly upon prediction-making on demand, with many astrologers constructing identities as counsellors and advisers.8 Fanti’s fortune-telling game is not dissimilar, culminating as it does in an advisory fortune for the reader. Texts that were widely disseminated in the late 15th and early 16th century propagated this counselling style of astronomy, among them Ptolemy’s Tetrabiblos, Abohali’s Book of Births and Albumasar’s Introductorium, alongside contemporary efforts such as the Almanach Nova by Johannes Stöffler, which enjoyed six printed editions in Italy between 1499 and 1531.9 The Triompho has been categorized specifically as a ‘lottery-oracle book’, alongside Lorenzo Spirito’s manuscript Libro delle Sorti of 1482 (Venezia, Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, Ms. It. ix, 87=6226) and Francesco Marcolini’s printed Giardino di Pensieri (Venice: Marcolini, 1540), a type in which the reader selects a question from a list and is directed through to an answer via some sort of chance operation.10 For this chance operation, Fanti created an interaction with a Rota Fortunae motif, situating the Triompho within a popular tradition of ludic use of Fortune’s wheel, as exemplified earlier by manuscripts such as Konrad Bollstatter’s compendium of ten lottery books, c.1450–73.11

However, reaching an advisory horoscope is evidently only one part of the purpose of this extraordinary book. Fanti takes every opportunity, both visual and verbal, to surround the player’s path through the game with advisory and polemical commentary, to the extent that it is perhaps better understood as a conduct manual in the form of a game.12 The astrological content is presented in such a pompous manner, and yet seems paradoxically to be of such limited and tangential relevance to the player’s experience of the game, that it feels more playful and satirical than it does scientific. Baldassare Castiglione’s closely contemporary Il Cortegiano, although now more often read straightforwardly as an advice manual, is of course also ludic in character: an example of the kind of conversation game described in Thomas Crane’s classic study.13 Playing the Triompho also represents a kind of ludic dialogue—with the book, and through it with Fanti, whilst simultaneously stimulating dialogue with companions. It is itself, potentially at least, a conversation game ranging across questions of ethics, behaviour and human nature. Classical and contemporary cultural references are woven throughout to imbue the game with additional layers of meaning, with visual and textual references to music functioning as a tool to this end—particularly in relation to discussions of love. In this way the Triompho could be compared to a cultural knowledge-based word game, such as giuoco dell’hoste (the game of the host).14

Playing the game

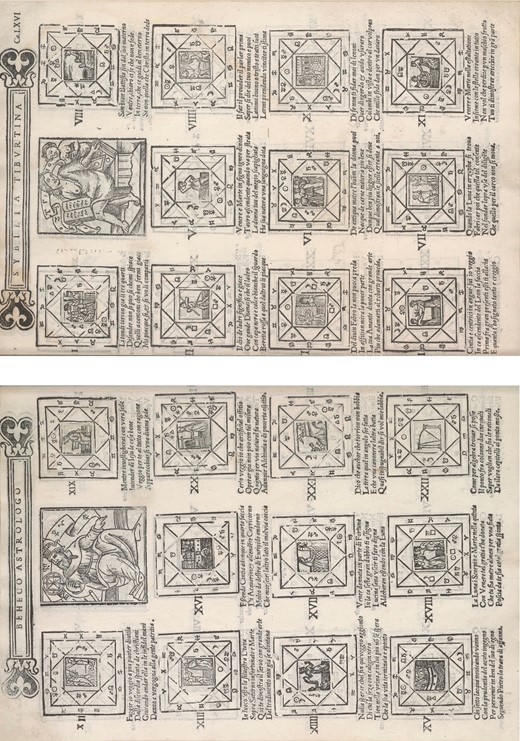

After a grandiose preface and playing instructions, the game begins with the set of Domande (initial Questions), each one accompanied by three small square Figure (Images) and a short commentary which together expand upon and clarify issues raised by the Domanda (illus.2).

![Fanti, Triompho di Fortuna: selection of Domande (initial Questions; sig.[cc1]r)](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/em/51/1/10.1093_em_caac068/1/m_caac068_fig2.jpeg?Expires=1747881849&Signature=2WkoKQi599bPSFm2j0hMUnasRAcxDAKnsCa7dwdyVSaRXiB7a6jgVeGMCKhUa~eRZOtjqIxZqTDndtBH~nTP-04bMEpaBJyDxFBw~TinVo~DQ-xABcg0IySAA3GYUDbn44gO9RwT7pLe-gH7xdEiCVELrU4BaczW6aPukF1q2WCI4zatSx-gzZ-mEifZHtErtID490S~anWsupbJX-XL3N9yT-9VCUNvw-8gNruQszU7kJ4qtAVWU4OOjuOKVERz~y-q22Cku0-A1J6gArwjziJHS0bkgpfTOp6ly-xitg~aX-Auz6FdynIqu7rGs5Yq7XVssS73jWar8Nq7U9DM1w__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Fanti, Triompho di Fortuna: selection of Domande (initial Questions; sig.[cc1]r)

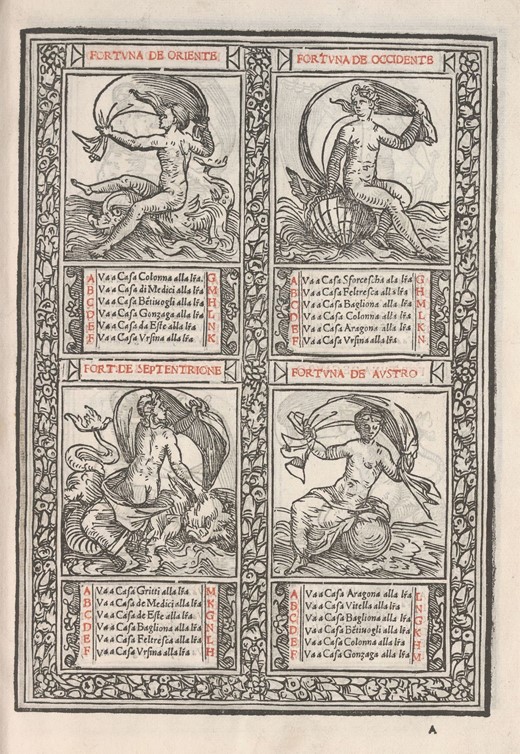

The questions range from matters of statecraft (for example, when to wage war) to more mundane life challenges (when to take a trip; when to make a purchase), and a great deal in between. Once the player has selected the question that best fits their situation, they read the instruction directing them forward to a specific letter marker within one of twelve Fortune (Fortunes; illus.3). These are named for the winds (and thus, by extension, the cardinal directions), and in turn direct the player on to a specific letter marker within one of twelve Case (Houses), named after prominent Italian ruling and noble families.

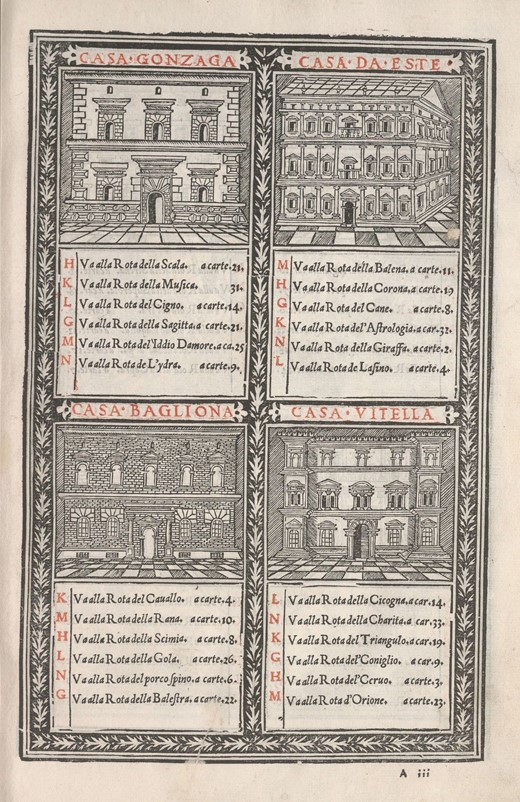

The Houses are represented by elegant images of palaces (illus.4). Each of the Houses has six exit routes, each pointing to a different Rota (Wheel), with no repetitions. In fact in terms of reaching a horoscope, the Fortunes and Houses are functionally redundant: there are 72 Questions, 72 routes through the Fortunes and 72 routes through the Houses. Thus Fanti could have connected the Questions directly to the Wheels and saved the player a lot of bother. The fact that he did not hints at the importance of the journey through the game, as opposed to its final objective, in Fanti’s conception.

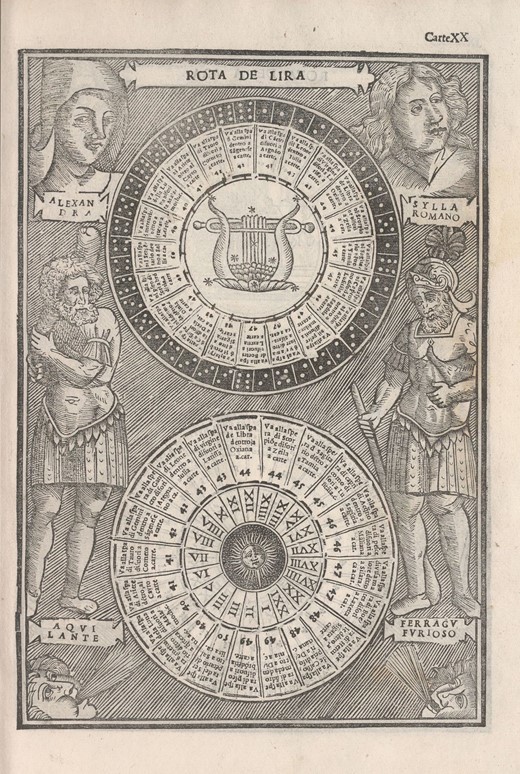

From this point things quickly become quite complicated, so for ease of navigation the rest of the book is organized into clearly labelled Carte (essentially, folios). Carte 1–36 contain the next phase of the game: the Rote (Wheels; illus.5). These are named after a bewildering variety of objects: 20 animals, two trees, the lily, crown, triangle, lyre and (pagan) altar; stairs, three ballistic weapons, Cepheus, Orion, Vulcan and Bacchus; the heart (pierced by an arrow), Cupid (as the God of Love), the seven deadly sins, the seven Liberal Arts (including Music), the theological and cardinal virtues, and finally Fortuna. Each Rota in fact has two wheels: an upper and a lower, one responding to a throw of two dice, the other to the time of day. This, presumably, is to allow for the possibility that no dice are to hand when playing the game. The upper wheel contains an illustration of the page’s titular entity; in cases where that entity was known as a constellation (such as Lyra), the stars are overlaid onto the illustration, giving the page a veneer of earnest astrological endeavour.

Fanti, Triompho di Fortuna: ‘Rota de Lire’ (Wheel of the Lyre; carta 20r)

The decorative borders of the Rote are rather elaborate. Most pages incorporate four portraits, each using an image drawn from a narrow range of types, but given a different name label upon each repetition—amounting to a huge portfolio of noteworthy persons both ancient and modern. The upper two portraits are busts in profile, while the lower two are full length (standing or seated). Some of the full-length portrait types leave space for a further pair of named portrait busts at the foot of the page, for a total of six. In all, there are 326 portraits among the Rote. The full-length portrait types include a standing man in sober dress featuring long robes and a Venetian bareta, playing the lira da braccio (illus.6) and a seated lutenist in more foppish courtly attire (illus.7). This dress style overlaps with that of the romantic canterino, a pastoral lutenist trope described in detail by Tim Shephard, Sanna Raninen, Serenella Sessini and Laura Stefanescu.15 Each of these lira and lute portraits is repeated nine times, with the majority of instances given the names of contemporary musicians, some of them easily identified: the Ferrarese court musicians Pietrobono (lute; carta 3v), (probably) Niccolo Tedesco (lute; carta 18v) and Agostino da Ferrara (lira; carta 21r), for example, and the celebrated poet-musicians Serafino Aquilano (lute; carta 15v) and Notturno Napoletano (lira; carta 26r). Ancient musicians are also in evidence, including the biblical Tubal (carta 5r),16 and the classical Orpheus and Arion, all playing the lira (carte 2v and 16v respectively). A few portraits have less-familiar names attached to them, such as ‘Frontino’ (lute, cartaIX;illus.7).17 Although these portraits as a whole have no technical function within the game, it is as if they are mirroring the environs of the player, ‘accompanying’ the game much as real-life musicians might have accompanied the participants in their post-dinner revelries.18 Perhaps, as they accompany the chance element of the game, they also suggest music’s manipulative abilities—a theme that will recur within the advisory horoscopes.

Portrait of Orpheus playing the lira da bracchio; detail from Fanti, Triompho di Fortuna: ‘Rota della Panthera’ (Wheel of the Panther; carta 2v)

Portrait of the poet and lutenist Serafino Aquilano (1466–1500); detail from Fanti, Triompho di Fortuna: ‘Rota de Pavone’ (Wheel of the Peacock; carta 15v)

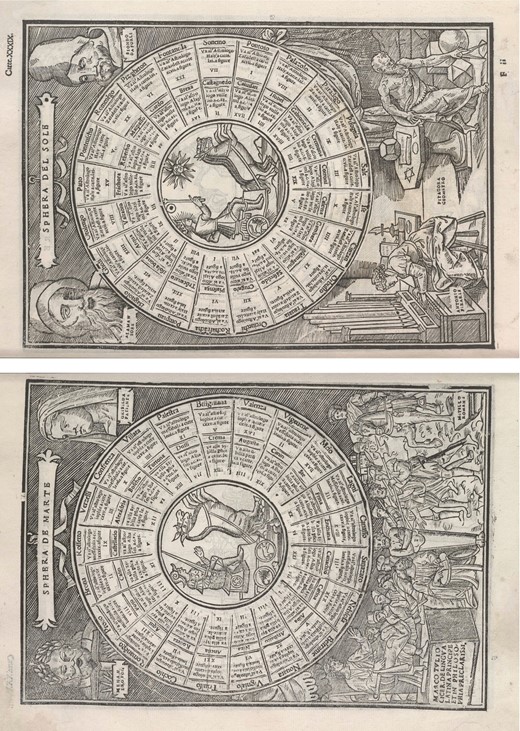

Each of the two Wheels on each page is split into 21 segments, each segment corresponding to a different outcome from throwing two dice, or a different hour of the day.19 These segments contain instructions as to how to proceed to the next phase of play, which is organized into Sphere (Spheres). The instruction in each segment states which Sphera to find, on which Carta; and within the Sphere, whether to seek the outer or inner circle, and which identifying word to look for. Each combination appears only once. The Spheres themselves (illus.8) are named after the eight mobile spheres (that is, the Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun; Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, the stars), 23 constellations, four elements (earth, water, air and fire), and finally hell (l’inferno).

Fanti, Triompho di Fortuna: two of the Sphere (Spheres; carte 38v–39r)

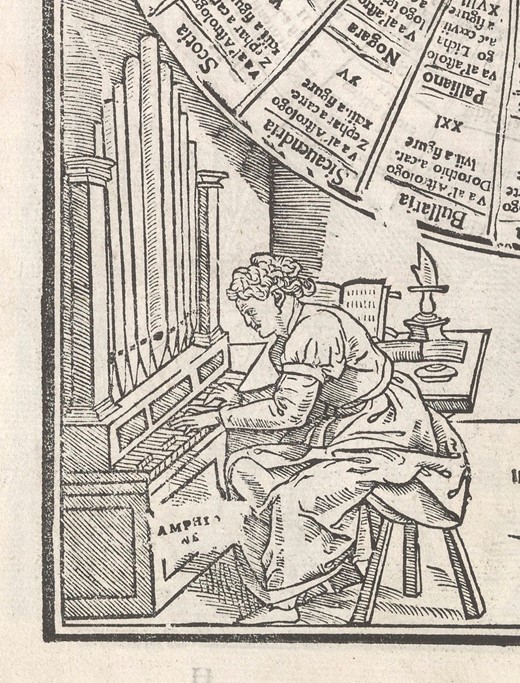

The decorative additions to the pages of Spheres comprise a gallery of famous orators, soldiers, sculptors, architects, musicians and geometricians in the lower margin, represented in vignettes that are repeated with different name labels; and a gallery of busts in the upper margin, again with repeating types given different names, featuring praiseworthy individuals—women as well as men—drawn largely from antiquity.20 Among these the musicians are presented as musical experts, or perhaps as composers of notated compositions: playing on an organ with a writing desk to their right-hand side, sitting on a stool that would allow easy transition between playing and writing (illus.9). Many of the names are evidently contemporary musicians—some of them easily identified, such as Antonio dall’Organo and Rudolph Agricola, both organists associated with the Este court chapel in Ferrara—but there is also the mythological musician Amphion. By contrasting with the musical portraits of the Rote, these are the most decorous and intellectual references to music in the Triompho, and present music-making unromantically, as a scholarly pursuit. Their inclusion here articulates erudition, contributing to Fanti’s scholarly guise—though in the ludic context, the impression created may have been rather more tongue-in-cheek.

Portrait of Amphion as an organist, from Fanti, Triompho di Fortuna: ‘Sphera de l’inferno’ (Sphere of Hell; carta 54v)

The Sphere themselves each contain two concentric circles of text, divided into segments. Each segment in each circle is titled; within a given Sphere the titles are all drawn from a single geographical category (for example: cities, countries, regions or rivers). Beneath each title is a concise instruction concerning to which astronomer or sibyl, on which Carta and with reference to which Figura, the reader should next proceed. Four astronomers or sibyls are named on each sphere.

The final and largest section of the book, running from carta 55 to carta 128, presents the horoscopes—that is, the answers to the questions posed at the outset (illus.10). Each Carta is presided over by a different noteworthy astrologer or sibyl, whose portrait (from a small selection of types) stands at its head. Each numbered answer comprises a quatrain (for the dubious poetic quality of which Fanti apologises in the preface), and a square image (Figura) which relates symbolically to the quatrain; each image appears at the centre of a small sky map or thema coeli, an arrangement commonly used in contemporary astrological guidebooks to indicate the particular celestial conjunctions that produce a given outcome.21 The subjects of the quatrains range from the direct to the ambiguous, encompassing both the erotic and the humorous. From the ensemble of Figura, thema coeli and poetic quatrain the reader is to infer the answer to the question that initiated their route through the game.

Fanti, Triompho di Fortuna: two carte (folios) showing Figure (woodcuts illustrating the fortunes told by the game; carte 55v–56r)

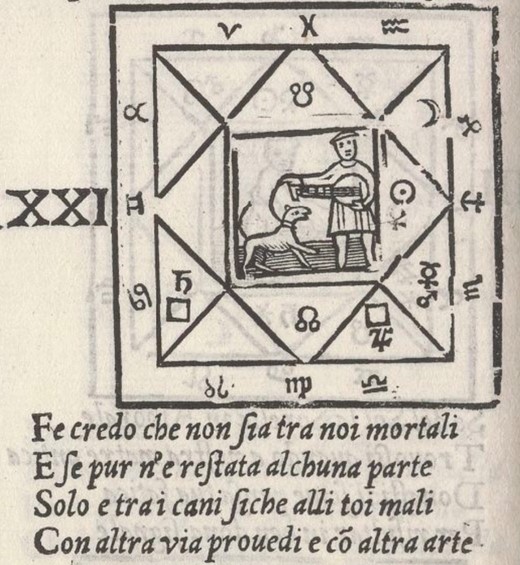

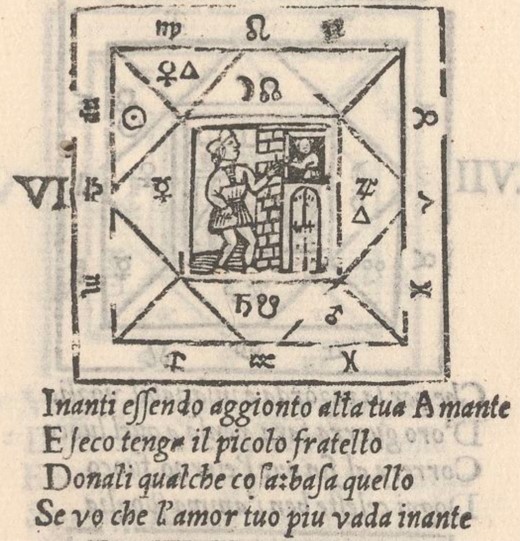

Among the repertory of Figure used in the opening and closing sections of the book are four which are explicitly or implicitly musical. One features an angel with a trumpet (illus.11, used three times); one a man holding a lute with a dog on a lead (illus.12, used four times); another a lutenist serenading a lady who stands in a doorway (illus.13, used seven times), while the fourth has a man addressing a woman who stands at a window or balcony (illus.14, used eight times). This final ensemble is strongly reminiscent of contemporary images showing the practice of bawdy (and, in many parts of Italy, illegal) nocturnal serenading known as mattinate.22 Each of the latter three images is used by Fanti in contexts connected with love in its various forms, and it is these images that form the focus of the remainder of this study (illuss.12–14).23

Fanti, Triompho di Fortuna: Figura showing an angel playing the trumpet (detail from carta 55v, XXI)

Fanti, Triompho di Fortuna: Figura showing a lutenist with a dog (detail from carta 56v, XXI; translation: Faith, I believe, is not among us mortals / And if it remains at all / It is only among the dogs; therefore for your ills / You must make provision in a different way and with a different art)

Fanti, Triompho di Fortuna: Figura showing a lutenist serenading a lady (carta 73r, VI; translation: With the head of a dragon on the fifth turn / The Lord ascends with Gemini; / Elegantly your lady allows / That she offers more the more you aim for)

Fanti, Triompho di Fortuna: Figura showing a balcony serenade (detail from carta 107r, VI; translation: Before being joined to your lover / Take in hand the little friar / Give it something: this is the foundation / If you want your love to go further)

Interpreting the musical Figure

That musical images in the Triompho are principally associated with matters of the heart is hardly surprising. As many scholars have observed and documented, music was paradigmatically associated with love in this as in many other periods—used by poets as a metaphor for romantic accord, cited as an effective tool for seducing both men and women, and serving as a vehicle for the expression of amorous sentiments in song.24 Music-making was also considered part of the courtship ritual, symbolic even of an elevated form of foreplay.25 Both the shapes of musical instruments and the movements required to play them were overlaid with widely known double entendres, and the sounds of singing likened to the passionate exclamations of sexual partners. If the association of music with love is entirely conventional, however, the Triompho images offer an interesting application thereof. Each occurrence of each image is either subtly or dramatically recontextualized by the changing questions, routes and quatrains by which the reader is guided to arrive at it. By virtue of music’s versatility as a vehicle for expression, a small repertory of musical scenes is able to deliver commentary on a wide range of ideas regarding the amorous relations of men and women of the period.

The introductory matter of the Triompho includes a section explaining the significance of the Figure, both in general terms and in some specific cases, making it clear that they deploy symbolism in a fairly straightforward way. The image showing man, lute and dog is discussed here alongside an image showing man, dog and elephant, and another showing Justice, as referring to good faith (illus.15). Fanti offers a detailed explanation in the text beneath:

![Fanti, Triompho di Fortuna: explanation of the Figure and quatrains (sig.[cc4]r–v)](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/em/51/1/10.1093_em_caac068/1/m_caac068_fig15.jpeg?Expires=1747881849&Signature=GmEwGvabMPHQgwtwZ8AGVDvv-Il2Wn4AWRzg5KYB3dSeBqapJAuFae92PSRVfx9QCaoF61dpXduieLC5ecc-TV8Z5wYOUfWH96LDXXFFayN1hhO3jyTdaAMr4y7GSBQtz8c8RlFn8mbKM5VjMbktiKXZKsar~ydjjv9NlLt9h5zJGsU1qaAPw1bANKKgCzA9-lU1rImlESpGbRKLdlxPtsaQUwvxayErhbhqwTezBfonUDGE3-WTEgu0XceOSkuu4IToKxcGZja2yyFQYtujaOq8XX4d2dMPFi-Yd~6ENTVeTcqEMLpxEOBwoaqpm1vGO7NZowcy8RXyrZHw9WULLA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Fanti, Triompho di Fortuna: explanation of the Figure and quatrains (sig.[cc4]r–v)

See here that the carefully designed image has its own particular meaning, as in the case of the image of the elephant and the dog, which are thought to be the most faithful animals in the world, and as the Author says much more faithful than man, because I submit that if you have your wife, or really any of your relatives whether of blood or of true friendship, they immediately disdain one another and do not want to come back any more, whereas with the faithfulness of the dog, or the elephant, this does not occur, but rather they always seek to return at any time. For that reason, the Author says in this quatrain, which is well worth committing to memory, which to be exact you will find under the dominion of the astrologer Albertegno:

Faith, I believe, is not among us mortals

And if it remains at all

It is only among the dogs; therefore for your ills

You must make provision in a different way and with a different art.26

Although this explanation seems to refer specifically to the image with the elephant and the dog, the quatrain appears again under the patronage of Albertegno at the other end of the book, accompanied by the image with dog and lute; thus it is clear that the interpretation applies to both dog-related images. Fanti makes no reference to the lute in either explanation or poem, but in contemporary works the instrument commonly appears in both verse and moralizing commentary as a symbol of the accord between friends or lovers, via the harmonious tuning and sympathetic resonance of its strings.27 In Andrea Alciato’s 1531 Emblematum liber, for instance, the lute is a symbol of good faith and friendship between rulers.28 Thus it is reasonable to read the lute in this particular image as, like the dog, a symbol of faithful friendship. Indeed, the image is reminiscent of the blind beggar-singer trope, in which a man is typically depicted with a stringed instrument and a dog.29 As one can just about make out from illustrations 12 and 15, the lutenist’s eyes are dots or lines, contrasting distinctly with the dog’s large, open eye. Faithful friendship, in that case, is even more poignant, given the marginalized and impoverished nature of the lutenist, and his reliance upon the dog for vision as well as safety and companionship.

Good faith transpires to be one of Fanti’s principal preoccupations in the Triompho, furnishing the subject for several of the longer commentaries in the Domande section. Among the concluding horoscopes to which the man, lute and dog image (illus.12) is also attached is one in answer to Domanda VII: ‘Whether the man will be grateful to his lord, or in reality to other princes’.30 The lengthy commentary appended to this question clarifies its meaning: Fanti rails against rulers who break faith with their subjects, servants and courtiers by failing to reward their years of good service. Following a route through Fortuna de Cauro (lettera A), Casa Vitella (lettera H), the Rota del Cervo (dice 3 + 5 / hour 9) and the Sphera de Gemini (Montesperello), the player reaches the following disheartening answer:

Povero te, come dispense li anni

Credendo gratia haver dal tuo signore

Perche il cortegi dimostra difuore

Un altro amor coperto de piu inganni.31

Poor you, spending years

Believing you have the favour of your lord,

Because his courtesy shows that externally

Whilst concealing another love with great deception.

Thus recontextualized, the accompanying image of a man with a dog and lute comes to represent a faithful retainer who, duped into thinking himself in favour, will in reality soon be betrayed by his lord who prefers another.

The question of good faith between men is given a powerfully gendered aspect in two game-paths which lead to horoscopes illustrated with the mattinata-like image (illus.14). Domanda XII, ‘If a man should follow the advice of a friend, or rather search his own soul’,32 calls forth from Fanti a lengthy diatribe against those who feign friendship to win the trust of another, only to take advantage of them later on. Such false friendship is increasingly common, Fanti notes, such that to guard against it ‘man should not seek any other friendship than that of God, or even that of himself, or of some small animal’ (recalling the dog).33 A route through Fortuna di Borea (lettera D), Casa Bagliona (lettera H), the Rota della Scimia (dice 2 + 2 / hour 12) and the Sphera de l’Inferno (Ussara), leads to an answer wholly in keeping with this jaundiced view of human relations:

Con fortunate le parte de amicitia

Con Gemini congionta egli ascendente

Gelosia te dimostra transparente

Cosa che gia non puoco del initia.34

With luck the parts of friendship

Ascend conjoined with Gemini

Showing you jealousy very clearly

Something which is already quite a sad beginning.

The nature of the jealousy that will eventually turn friendship into betrayal is implied by the accompanying mattinata image, which in essence presents a man attempting, under cover of darkness, to seduce another’s wife. Whilst the dog-loving lutenist presents sound as a metaphor for friendly accord, here sound takes on a quite different character, its ephemeral nature allowing it to penetrate the wifely decorum otherwise preserved by the walls of the house, as Flora Dennis has observed. Windows and balconies were problematic sites of feminine self-display in early modern cities, the limited accessibility they afforded in tension with the secure enclosures of both house and body—a dialogue highlighted in the image through the firmly shut doors visible beneath the woman at ground-floor level.35 Here, the sonic violation of both house and marriage, perhaps by a trusted friend, is a powerful symbol of betrayal. The immorality of the unfaithful seduction is mirrored by the illegality of the mattinata, extending the violation of house and marriage to that of the state and its law. Tellingly, the same horoscope can also be reached by another route, beginning with Domanda LXVII, ‘When is a good time to sell, or buy?’36 Fanti’s theme here, clarified in the commentary accompanying the question, is fraudulent dealing—another example of bad faith.

For Fanti, women are no mere pawns in this game of betrayal. ‘All the misfortunes and adverse events, which can assail a man in this life, almost always arise from women’, he complains in his commentary on Domanda XXVII, which asks ‘How will matters unfold between husband and wife, and what can the husband do to avert it before he takes her home?’.37 He goes on to advise grooms that they should take receipt of their dowry before allowing their bride into their house—otherwise dishonest dealings will surely follow. This question stands at the head of a route through Fortuna de Septentrione (lettera D), Casa Bagliona (lettera N), the Rota del Porco Spino (dice 3 + 5 / hour 16) and the Sphera de Scorpione (Zailani), culminating in another instance of the mattinata image, this time accompanying a quatrain on a decidedly unhappy marriage:

Ligato essendo nel Hymineo laccio

Di Marte in l’hora Acquario ascendete

Infelice la Luna ella dolente

La veggio star che sei fredo qual giaccio.38

Being trapped in Hymen’s snare

Of Mars ascending in the hour of Aquarius

Unhappy the Moon, she in sorrow

I see remain there as cold as ice.

Here the mattinata scenario reinforces the idea of rejection, though it could also imply infidelity as the reason for the infelicitous match, as we see the wife wooed by another man. This is a situation to which Fanti thinks women particularly susceptible, as he reveals in his commentary to Domanda XXV, ‘How many husbands will the woman have?’.39 Here, the Author exhorts every woman to have no more than two husbands, or three at the most, when she cannot do otherwise, in order to preserve her honour.40 If she has more, she gives a very clear sign of being unchaste—and all the more so when she abandons her young children for her new husband. Fanti says that the love of the father for his children is much greater than that of the mother, because the father never abandons them, whereas she does so in order to satisfy her ‘dishonest’ appetite (‘disshonesto appetito’). This question does not yield a path to a horoscope with a musical image, but the Figura of a lutenist serenading a woman is one of the three images printed alongside the question itself, citing once again the role of music in dishonestly undoing Hymen’s knot.

A more charitable view of wives is allowed by Fanti in response to Domanda XXIII, ‘Whether it is better to take to himself a beautiful, or an ugly woman’.41 In the question commentary, Fanti lauds the happiness of those whose wives are both beautiful and good: ‘but because no one can be found who is perfectly beautiful, he says that at least, for your satisfaction, she ought to be beautiful in some respect, although beauty is understood in many ways’.42 The answers reached from this question, accordingly, describe different ways in which women can offer their prospective husbands more than first meets the eye. Two paths pass through the Rota del Giglio (Wheel of the Lily—a symbol of virginity) to horoscopes illustrated by the lutenist serenading a lady. One (dice 4 + 6 / hour 10) leads to the quatrain ‘Because Venus is renewed with Jupiter / Rays flashing in the midst of the sky / At their birth, by her cheeks I conceal / Her high beauty amidst the other renewal’, implying that at certain times the beloved’s face will flush, revealing her beauty.43 There is an implication in this ensemble that making music to your lover—an activity regularly cited in the period as causing a quickened pulse and a state of arousal, especially in women—may be precisely what is needed to bring out her hidden beauty.44 The other path (dice 3 + 4 / hour 5) leads to another iteration of the serenading lutenist, and carries a similar implication that the man can coax greater perfection out of his beloved: ‘Elegantly your lady allows / That she offers more the more you aim for’.45 If these horoscopes are consonant with contemporary ideas on the role of music in seduction, they also recall commonplace advice to husbands that they must coach and mould their wives, correcting their purported faults. One of the wifely discussants in Erasmus’s Christiani matrimonii institutio, which reached print in 1526, exclaims after such tuition: ‘Oh, how lucky I was to find such a husband! What a mindless creature I would have been without such a teacher!’46 Thus, without losing its sensuous physiological effect, music-making pivots in these cases from dangerous seduction to entirely proper, conjugal coaxing and cultivating.

The implication that external beauty and internal virtue go hand in hand, a commonplace of contemporary culture, is extended by Fanti to men.47 In his commentary on the question ‘If the man’s physiognomy is good, or not’, he claims that he will reveal, thanks to the ancient and exotic science of physiognomy, ‘the true knowledge of the nature of any man, by means of the lineaments of the face, and the proportion of the members’.48 Despite the grand claim (itself perhaps for comic effect), Fanti exploits this topic for its humorous potential. Following a route through Fortuna de Borea (lettera F), Casa Colonna (lettera M), the Rota di Cepheo (dice 2 + 4 / hour 19) and the Sphera della Terra (Silda), the player reaches an extremely insulting quatrain accompanied by the Figura of the lutenist serenading a lady, clearly intended to provoke mirth in the player’s companions:

Large narice e grosse al naso infisse

L’huomo disigna esser venero certo

Et chi piu larghe l’ha io dico aperto

Piu fia sdegnoso in l’amorose risse.49

Big fat nostrils attached to the nose

He wishes to be revered for sure

And he who has a bigger one, I say openly,

Will be more contemptuous in the battles of love.50

It is initially perhaps a little surprising that this Pantalone-like lover, a figure of ridicule with a nose as big as his ego, is paired with the image of a lutenist serenading a lady. In this case, rather than a solicitous husband playing for the stimulation and improvement of his imperfect wife, the scene is turned on its head to amplify the man’s amorous absurdity. In a much-cited passage from Il Cortegiano, Castiglione’s Messer Federico pronounced that old men should not perform music in the presence of ladies, as their unlovely appearance (specifically: hoary, toothless and wrinkled) makes the protestations of love in their songs seem ridiculous.51 Similarly, Fanti’s ‘revered’ big-nose is all the more absurd for having taken up his lute to enter a battle of love. Nevertheless, Fanti offers the player a ray of hope in their unfortunate situation: in the question commentary he encourages the ugly to counteract their evil nature through good and holy conduct. This comment reflects contemporary advice concerning the careful fashioning of the self with the help of inspiring props—such as portraits of praiseworthy ancestors, and a mirror to check how your own countenance shapes up to their noble features.52

Two further Domande lead to multiple musical images. Both are concerned with courtship in what Fanti clearly considers a more light-hearted vein, without engaging ethical issues to any great extent, as indicated by their commentaries. Domanda XVI asks ‘If the Beloved returns the love of the Lover’, leading, appropriately, to the Rota del Dio d’Amore.53 Both musical routes leading from this question refer to jilted lovers of classical antiquity. One (dice 5 + 6 / hour 19) takes the player to a quatrain revealing the player’s lover to be ‘non quella di Cartago’ (not that of Carthage): unlike the faithful Queen Dido, who committed suicide when abandoned by Aeneas, the beloved is receptive to the adulterous advances of the mattinata performer beneath her window.54 The other route (dice 1 + 6 / hour 5) leads to the image showing a lutenist serenading a lady, and a quatrain referring to Vulcan’s plot to catch his adulterous wife Venus in the act with her lover Mars. The player can only watch the depicted serenade in despair, because under the influence of a musical seduction, ‘Rather than loving you, she prepares to reject you’.55 Here, we are back on the theme of good faith, about which Fanti was so much exercised.

By far the largest number of routes (six) to a musical Figura start out from Domanda XVII, ‘If you wish to be loved by your beloved’,56 and pass through the Rota della Speranza. The answers give morally questionable advice on seduction—somewhat in the vein of Ovid’s Ars Amatoria, which was a print bestseller in the period. Indeed, Fanti notes that he included the question ‘solely to have a reason to treat of secret cases of love, where he narrates many subtle inventions and tricks, very delightful to hear of, that lovers are prone to use towards each other’.57

Three of the musical horoscopes to which this question can lead (dice 1 + 4 / hour 9; dice 6 + 6 / hour 5; dice 5 + 5 / hour 3) suggest ways in which the lover might woo his beloved, accompanying this advice with the image of a lutenist serenading a lady. Two of these stress the value of strategically ‘bumping into’ one’s beloved whilst showing off at parties, with the implication (in one case explicitly mentioned in the quatrain) that musical skills are valuable in that context; the third advises showering her with beautiful clothes and jewellery, because ‘che in cose tal spesso dame vanegia’ (ladies are crazy about things like these).58 As Tim Shephard and his colleagues have recently observed, in the course of the first three decades of the 16th century in Italy the image of a youthful lutenist became firmly established as a shorthand for an amorous inclination, formulated loosely within the parameters of Pietro Bembo’s elegant and popular blending of petrarchismo and Neoplatonism.59 A player could relate the lutenist Figure to Fanti’s Rote portraits of contemporary (self-fashioned) canterini, such as Serafino Aquilano, uniting the visual and aural senses and reinforcing the fusion of music and romance.60 In the case of these three horoscopes, the image of a man playing his lute to a woman is taken to be a sufficiently generic representation of courtship to apply to any such situation, whether or not music is specifically mentioned by the quatrain.

The other three musical predictions (dice 1 + 3 / hour 8; dice 1 + 1 / hour 6; dice 4 + 4 / hour 21) use the mattinata image alongside quatrains that explicitly engage with the setting of a midnight tryst. One notes that, if a lover (from her balcony) is giving eye and ear to one’s performance despite the wind, rain and ice of a midnight storm, ‘It is impossible that love in the end will not place her in your arms’.61 The remaining two give advice for the illicit sexual encounter that may follow. The lover is directed to masturbate beforehand so that the intercourse can last longer:

Inanti essendo aggionto alla tua Amante

E seco tenga il picolo fratello

Donali qualche cosa: basa quello

Se vo che l’amor tuo piu vada inante.62

Before being joined to your lover

Take in hand the little friar63

Give it something: this is the foundation

If you want your love to go further.

And Fanti describes one of the ‘subtle inventions’ used to kindle stronger love between lovers:

Solicito e secreto esser conviensi

Giongervolendo al disiato luoco

Il permetter l’anel curalo puoco

Et fa che occulti itoi piacer despensi.64

Solicitous and secret, to gain admittance

Wishing to join at the desired place

Allow it to attend to the ring a little

And make it so that in hiding your pleasures are dispensed.

Fanti’s advice to the player (notably, probably a woman in this case) is to allow anal sex in order to gain love from their lover.65 Framing this advisory quatrain is Pietro Aretino’s scandalous Ragionamenti, first printed in 1534. In it, the courtesan Nanna notes that men seemed to relish anal sex more than did women, who in her experience did not enjoy it—presumably, hence the need for women to be persuaded by the promise of love in return. The phrase ‘gain admittance’ invokes the doors, currently closed beneath the woman at the balcony, and the persuasive, perhaps bargaining element of this quatrain.66

Together, these vignettes clarify and characterize the balcony scene, confirming the implications it brings to its other uses discussed above: it is an illicit sonic performance designed to seduce and cuckold. Stories of such night-time encounters were reasonably common in the popular literature of the day—told by Boccaccio, and by Poggio Bracciolini in his bestselling Facetiae (1470), for example. The entertaining tone of these novellae is closely aligned with Fanti’s stated intention to delight the reader with the secret connivances of lovers, and contrasts sharply with the hectoring and high-minded mode found in some other portions of the Triompho.

*

For all the humour and eroticism infused in these latter two quatrains, issues of gender underpin the thematic contexts of music and love throughout Fanti’s Triompho, and are the subject of the most moralizing, critical and problematic content in the book. For the purposes of this study, it is worth highlighting the binary gender characterization depicted by Fanti in his musical images, and their corresponding fortunes. Women’s involvement within the book is significant: the fact that they are considered active users of the book, rather than assuming a men-only readership, is notable (for example, as we have seen, they are exhorted to take as few husbands as possible). However, one cannot ignore the fact that women are often described in a derisive tone, and using misogynistic tropes. Despite the marginally more nuanced discussions of, for example, female beauty, the repeated musical Figure convey negative messages about women and their ‘natures’; their infidelity, their manipulability, and other generalized, negative framings of their behaviour such as their sexual appetites and vanity. For example, the mattinate image, conveying a woman in the liminal space between private and public spheres, is often accompanied by the sexually explicit Fortune. This reinforces the idea that women with any amount of freedom (as represented by the balcony) are prone to act immorally, and thus (Fanti tells us repeatedly) must be controlled, coerced and dominated (represented, in part, by the closed doors of the image).

Fanti’s stereotyping of men is much more limited in relation to these musical Figure: ultimately men are framed as capable of utilizing music to manipulate women, and are also identified as the victims of unfaithful (manipulated?) women. The most negative association with male behaviour in the context of the musical images is one of infidelity, not in their romantic relationships with women, but with regards to their friendships with other men. Early in the book we encounter this unfaithfulness in the context of the court (though there is much more to be said on the ‘favour’ of Lords in a courtly context, which could add greatly to the discussion of love and gender), with the lutenist and dog image anchoring the theme of fidelity. Later, we may encounter male infidelity in terms ‘stealing’ another man’s wife or lover. This is still framed in terms of the woman’s bad nature, rather than the immoral behaviour of the man; the instance of male infidelity is merely implied. In any case, Fanti depicts men as powerful and capable of control—unless, of course, their physical appearance subverted the cultural norm (another topic ripe for discussion).

To conclude, it is worth returning to the book’s self-declared purpose: to be a ‘magnificent game’. Though the Triompho is indeed a game, it does not rely upon (although it also does not exclude) interactive gameplay to entertain the player. Rather, it is about the journey through the book, from the Domande to the quatrains, passing through each stage, encountering Fanti’s carefully placed pictorial references to contemporary culture, and thereby amusing, insulting, instructing and delighting the player or reader. Throughout gameplay, one encounters multiple musical references, from portraits of lauded 16th-century musicians to quatrains utilizing music to communicate about love. Thanks to the versatility of these repeated images, and the ubiquity of music in the cultural fabric, the mere depiction of a lutenist or singer at a balcony could convey numerous relatable narratives, shared values and ideas, enriching the experience of the player. Continued investigation of this work will undoubtedly reveal further insights.

Annabelle Page is a Musicology DPhil student at the University of Oxford, studying the development of Claudio Monteverdi’s public image and persona over the course of his career. She completed a Masters in Musicology at the University of Sheffield in 2018, in which she began to explore the musical imagery in the Triompho di Fortuna. [email protected]

Footnotes

On this form of upper-class early modern gaming, see Don Beecher’s introduction to Straparola’s The Pleasant Nights (Toronto, 2012), esp. pp.28–38. On women in Veglie, see M. Feldman. Opera and sovereignty: transforming myths in eighteenth-century Italy (Chicago, 2007), p.357.

The date is given in the colophon as January 1526 according to contemporary Venetian usage; thus some copies are miscatalogued with a date of 1526.

Sigismondo Fanti, Triompho di Fortuna (Venice, 1527), sig.[aa]r; Christ Church Picture Gallery, jbs 358 (inv. 0137). Sheryl E. Reiss gives a brief history of the attribution debate in From Raphael to Carracci: the art of papal Rome, ed. D. Franklin (Ottawa, 2009), p.171. Some have compared Peruzzi’s style directly with the Triompho’s Fortune (see illus.3); see G. Gandolfi and M. Calabresi, ‘Et summis surgentia tecta sub astris: Villa Farnesina come edificio astrologicamente orientato’, in Ex Oriente: Mithra and the others, ed. E. Antonello (Padua, 2021), pp.223–42, at p.234. However, the gallery suggested that their drawing could well have been obtained by the printer or publisher and used without Peruzzi’s involvement. I have found a portrait of ‘Baldasar Senese’, likely the Sienese Peruzzi, on the ‘Rota del Barbigianni’ (carta XVI), indicating that Fanti at the very least held knowledge of the artist, and saw him as culturally significant. By comparison, accompanying the ‘Rote delle Fede’ (Wheel of Faith) there is a ‘Fanto Fer.’ portrait opposite one labelled ‘Dosso Pictor’. Given the significance of faithfulness in the book, I am inclined to believe that this could refer to some form of collaboration. I am very grateful to Jacqueline Thalmann from the CCPG for her input on this matter.

Since the Triompho di Fortuna does not contain page numbers, I use the printer’s signatures to refer to specific locations up to sig.a3v. Thereafter references refer to the labelled carte, I–CXXVIII, though adopting Arabic numerals; any Roman numeral following this refers to the specific numbered item (usually a poetic quatrain and accompanying Figura) on the page. So, for example, ‘carta 123v, XXI’ would refer to the quatrain labelled ‘XXI’ on the reverse of the page labelled ‘[carta] CXXIII’.

A. Biondi, ‘Sigismondo Fanti e i libri de la sorte’, in Triompho di Fortuna, facs. edn (Modena, 1983), p.8.

Marino Sanudo, I diarii di Marino Sanuto [1496–1533], xliii (Venice, 1895), p.421.

Marcantonio Guarini, Compendio historico … della diocesi di Ferrara (Ferrara, 1621), Lib.3, fol.274.

B. Dooley, A companion to astrology in the Renaissance (Boston, 2014), p.9.

Dooley, Companion to astrology, p.3.

R. Eisler, ‘The frontispiece to Sigismondo Fanti’s Triompho di Fortuna’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, x (1947), pp.155–9, at p.157.

See J. Kelly, ‘Predictive play: wheels of fortune in the early modern lottery book’, in Playthings in early modernity: party games, word games, mind games, ed. A. Levy (Kalamazoo, 2017), pp.145–66, at pp.147–8.

Play and morality/moralizing frequently overlapped in 16th-century games; see A. L. Palmer, ‘Lorenzo “Spirit” Gualtieri’s “Libro Delle Sorti” in Renaissance Perugia’, The Sixteenth Century Journal, xlvii/3 (2016), pp.557–78, at p.558; K. Wood, ‘Chancing it: print, play, and gambling games at the end of the sixteenth century’, Art History, xlii/3 (2019), pp.450–81, at pp.460–64.

T. F. Crane, Italian social customs of the sixteenth century (New Haven, 1920), pp.263–4.

K. Wood, ‘Performing pictures: parlor games and visual engagement in Ascanio de’ Mori’s Giuoco piacevole’, in Playthings in early modernity, ed. Levy, pp.9–28, at pp.12–16. A detailed comparison between game books would be labour-intensive but enlightening. I have observed commonalities between Marcolini, Spirito, Bollstatter and Fanti including wheels of fortune, portraits (of some description), questions on love and relationships, classical references and a similar approach to the mechanics of the game (such as a chance element, question-and-answer format). So far, Fanti seems to be the most prolific user of musical references, though further study is required to corroborate this.

T. Shephard, S. Raninen, S. Sessini and L. Stefanescu, Music in the art of Renaissance Italy 1420–1540 (London, 2020), pp.256, 264, 310–11, 316, 324; see also C. Henry, ‘Alter Orpheus: masks of virtuosity in Renaissance portraits of musical improvisers’, Italian Studies, lxxi/2 (2016), pp.238–58, at p.243.

Although it is Jubal who is more commonly depicted with his lyre as Father of Music, the Rota del Dracone clearly labels its lira da bracchio player as ‘Tubal’. There is perhaps some confusion here with Jubal’s half-brother in Genesis iv, Tubal-Cain, though note that Nicolò Malermi’s Italian Bible of 1471 says that ‘tubal esso fu patre de li cantanti in cythara & organo’ (Tubal was the father of singing on the cithara and organ); see for example Malermi, Biblia vulgare istoriata (Venice: Giovanni Ragazzo, for Lucantonio Giunta, 1490), fol.b2r; Oxford, Bodleian Library, Douce 244, digitized at https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/492fe240-6937-411b-80a5-90bceed299fe/surfaces/b2701038-ebcb-456f-95f9-266815b114de/ (accessed 17 October 2022).

An in-depth study of these portraits would make a compelling study. Identifying them has been a difficult task, and there are still a few without a clear identity, including ‘Frontino’. My thanks to Bonnie J. Blackburn for her contribution to identifying some of these mysterious figures.

The salon environment in which games such as the Triompho would have been played is described vividly in Wood, ‘Performing pictures’, pp.12–14.

Fanti’s instructions on sig.aa3r note that for hours 22:00, 23:00 and 24:00, the player should adopt the instructions of segments 01:00, 02:00 and 03:00 respectively. No explanation is given for the dice rolls (as far as I have found), so one assumes that the player must reroll until they roll one of the 21 totals given by Fanti.

There are 144 portraits in total in the Sphere section, nine of which are organists; each set of four portraits is repeated nine times.

G. Bezza, ‘Representation of the skies and the astrological chart’, in A companion to astrology in the Renaissance, ed. Dooley, p.59.

Compare the mattinata images discussed in F. Dennis, ‘Sound and domestic space in fifteenth and sixteenth-century Italy’, Studies in the Decorative Arts, xvi/1 (2008–9), pp.7–19, at pp.13–15; and F. Dennis, ‘Unlocking the gates of chastity: music and the erotic in the domestic sphere in fifteenth and sixteenth-century Italy’, in Erotic cultures of Renaissance Italy, ed. S. F. Matthews-Grieco (Aldershot, 2010), pp.223–45, at pp.235–7.

Illustrations 12–14 show examples of these three musical Figure, each alongside one of its associated quatrains. The romantic and sexual natures of illustrations 13 and 14 will be analysed and discussed later in the article. All translations from the Triompho in this study are my own.

See especially M. Feldman and B. Gordon, The courtesan’s arts (Oxford, 2006); Dennis, ‘Unlocking the gates of chastity’; B. J. Blackburn and L. Stras, Eroticism in early modern music (New York, 2015); and Shephard et al., Music in the art of Renaissance Italy, pp.223–43.

This is illustrated by the ‘ubiquitous’ Garden of Love print by Baccio Baldini; see C. Henry, ‘Leonardo da Vinci, parody and pictorial magic’, in Playthings in early modernity, ed. Levy, pp.73–96, at pp.81 and 83.

Fanti, Triompho di Fortuna, sig.[cc4]r–v; for the original Italian, see illustration 15.

For examples, see Shephard et al., Music in the art of Renaissance Italy, pp.256, 264, 310–11, 316, 324.

Andrea Alciato, Emblematum liber (Augsburg: Heinrich Steyner, 1531), sig.a2v–a3r.

C. Henry, ‘From beggar to virtuoso: the street singer in the Netherlandish visual tradition, 1500–1600’, Renaissance Studies, xxxiii (2019), pp.136–58, at p.140.

Fanti, Triompho di Fortuna, sig.bb2r: ‘Se l’huomo sara grato suo signore o veramente ad altri principi’.

Fanti, Triompho, carta 103r, VI.

Fanti, Triompho, sig.bb3r: ‘Se l’huomo si de riposare sopra le parole del amico, omeglio ricercar del animo suo’.

Fanti, Triompho, sig.bb3v: ‘che l’huomo non debba cercare altra amicitial che qualla di Dio, e puoi qualla di se medesimo, e di qualche animaletto …’.

Fanti, Triompho, carta 92v, XIX.

A. Cowan, ‘Seeing is believing: urban gossip and the balcony in early modern Venice’, in Gender and the city before modernity, ed. L. Foxhall and G. Neher (Hoboken, NJ, 2012), pp.231–48, at p.235.

Fanti, Triompho, sig.[cc3]r: ‘Quando e buon vendere, o comprare’.

Fanti, Triompho, sig.bb5r: ‘come tutti glinfortuni e casi aversi, che a l’huomo possa nella presente vita intervenire, nascono quasi sempre dale femine’; ‘Quello che fra’l marito e la moglie de avenire, et quello, che il marito de avertire prima che se la meni a casa’.

Fanti, Triompho, carta 72v, XIX.

Fanti, Triompho, sig.bb5r: ‘Quanti mariti havera la donna’.

Fanti does not specify when the women should take these husbands, but one imagines he means in succession, if widowed. It is interesting to compare this with the male equivalent question on sig.bb4v, ‘Quante donne l’huomo debbe pigliar’ (how many women should a man take?). Fanti suggests the same number, two to three, exhorting men not to take more and show themselves to be ruffiani (pimps), making a marcatatia di femine (a market for women). It is still unclear, however, if Fanti means for men to take no more than two or three women at once, or in succession—‘taking women’ is more ambiguous (with ‘take’ in particular reasserting the unequal power dynamic between men and women) than ‘having husbands’.

Fanti, Triompho, sig.bb4v: ‘Se glie bene a pigliar bella, or bruta donna’.

Fanti, Triompho, sig.bb4v: ‘Ma perche nessuna sene trova, che sia perfettamente bella dice, che almeno, per sua satisfatione, la debba torre, che n’habbia qualche parte, quantunque le bellezze s’intendano in piu modi …’.

Fanti, Triompho, carta 78r, XI: ‘Per che Vener con Giove se rinova / I lampegianti raggi in megio il cielo / Nel nascer suoi per le sue guanze io celo / L’alta beltate sua tra l’altre nova’.

On the influence of music on pulse in contemporary medical understanding, see J. Hatter, ‘Col tempo: musical time, aging and sexuality in 16th-century Venetian paintings’, Early Music, xxxix/1 (2011), pp.3–14.

Fanti, Triompho, carta 73r, VI; for the original Italian see illustration 13.

J. W. O’Malley and L. A. Perraud, Collected works of Erasmus: Spiritualia and Pastoralia (Toronto, 1999), p.375.

On beauty and virtue, see, among others, L. Syson and D. Thornton, Objects of virtue: art in Renaissance Italy (London, 2001), pp.51–6.

Fanti, Triompho, sig.[bb6]r, Domanda XXXVI: ‘se la phisonomia de l’huomo e buona, o no’; ‘… la vera cognitione della natura di qualunque huomo, mediate I liniamenti del volto, e la proportione de membri …’.

Fanti, Triompho, carta 94r, VIII.

There is a potential argument that the ‘nostrils’ and ‘nose’ in this quatrain are a phallic cipher, and that Fanti is warning players that size is no insurance of a good lover. The nose–penis link is associated with an adage attributed to Ovid, ‘Noscitur e naso quanta sit hasta viro’ (A man’s penis is known from the size of his nose), but it is also a feature of early modern antisemitism; see D. Harrán, ‘The Jewish nose in early modern art and music’, Renaissance Studies, xxviii/1 (2014), pp.50–70, particularly p.58 onwards.

Baldassare Castiglione, The book of the courtier, trans. G. Bull (London, 1967), p.121.

See T. Shephard, ‘A mirror for princes: the Ferrarese mirror frame in the V&A and the instruction of heirs’, Journal of Design History, xxvi/1 (2013), pp.104–14.

Fanti, Triompho, sig.bb4r: ‘Se l’Amata con l’Amante corrisponde in Amore’.

Fanti, Triompho, carta 88r, IIII.

Fanti, Triompho, carta 66r, III: ‘Piu che adamarti al rebarti proveda’.

Fanti, Triompho, sig.bb4r, ‘Se d’esser amato dall’Amata desideri’.

Fanti, Triompho, sig.bb4r: ‘La presenteperposta e’ fatta dall’auttore solamente per haver cagione da puoter trattar de secreti casi d’amore, dove narra assai sotili inventioni e astutie, molto dilettevoli ad intendere, che gli amanti sogliono l’uno verso dell’altro usare’.

Fanti, Triompho, carta 102r, I (this carta is misnumbered 105).

Shephard et al., Music in the art of Renaissance Italy, pp.305–14. See also V. Coelho, ‘Bronzino’s lute player: music and youth culture in Renaissance Florence’, in Renaissance studies in honor of Joseph Connors, ed. M. Israëls and L. A. Waldman, 2 vols. (Cambridge, MA, 2013), pp.650–59.

A description of the interplay between parlour games, including those in books, and the senses is given in Wood, ‘Performing pictures’, p.24. On Serafino Aquilano’s canterino status, see for example B. Wilson, ‘The Cantastorie/Canterino/Cantimbanco as musician’, Italian Studies, lxxi/2 (2016), pp.154–70, at p.166.

Fanti, Triompho, carta 101v, XXI: ‘Esser gia non puotra cotanto proda/ Che amor al fin non te la poggia in braccio’.

Fanti, Triompho, carta 107r, VI.

On the translation and interpretation of the euphemism ‘picolo fratello’ (little friar = penis), see V. Boggione and G. Casalegno, Dizionario del lessico erotico (Turin, 2004), p.230.

Fanti, Triompho, carta 99v, XIX.

This could be read as a humorous suggestion from Fanti, who claimed that he included the associated Domanda so that he could discuss the ‘tricks’ and ‘inventions’ used by lovers to love one another—subjects befitting the convivial setting in which this game book would be played. However, it could also be read in terms of its coercive nature: if the woman wants romantic love from her lover, Fanti suggests, she may get it by allowing a sexual act she would not usually consent to (if we are to believe Aretino’s writings; see n.66 below). In the context of Fanti’s statements on the necessity of men controlling women, perhaps this should be read as another normalization of the coercion of women by men, this time, in a sexual context.

Aretino’s dialogues, ed. and trans. M. Rosenthal and R. Rosenthal (Toronto, 2018), p.34; Pietro Aretino, The school of whoredom (London, 2003), p.11.