-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Peter Holman, Handel’s harpsichords revisited Part I: Handel and Ruckers harpsichords, Early Music, Volume 49, Issue 2, May 2021, Pages 227–243, https://doi.org/10.1093/em/caab027

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The harpsichords supposedly owned or played by Handel have long been the subject of scholarly enquiry, in recent years mainly to try to match their compasses and disposition to his solo music, a strategy also used, for instance, with instruments associated with J. S. Bach and Mozart. Similarly, Grant O’Brien, John Koster and others have tried to determine how Ruckers-family instruments might have been used to play early 17th-century keyboard music.

In these two articles I will survey the plucked keyboard instruments that have been associated with Handel from the composer’s time to the present. The focus in Part I is on three surviving Ruckers harpsichords that were promoted as ‘Handel’s harpsichord’ in the 18th and 19th centuries. A good deal of new information about them has come to light as the result of the recent projects to digitize newspapers, journals and other 18th- and 19th-century documents. This has enabled me to trace their provenance in greater detail than before, and to place them in the context of the process of importing, modernizing and circulating instruments by the Ruckers-Couchet family of Antwerp in 18th-century England. Evidence has also come to light of three more Ruckers instruments said to have been owned and used by Handel or his followers, making six in all, helping us to understand how they were used and why they might have preferred these obsolete instruments to the larger and more modern ones by London makers such as Shudi and Kirkman.

The harpsichords supposedly owned or played by Handel have long been the subject of scholarly enquiry,1 in recent years mainly to try to match their compasses and disposition to his solo music. This strategy has also been used, for instance, with instruments associated with J. S. Bach and Mozart.2 Similarly, Grant O’Brien, John Koster and others have tried to determine how Ruckers-family instruments might have been used to play early 17th-century keyboard music.3 However, this approach will not necessarily work for Handel because it seems that he used a number of harpsichords as the keyboards from which he directed oratorios, playing continuo rather than solos—a practice followed by his associates and followers. This explains why one of the instruments long associated with him, the single-manual Andreas Ruckers harpsichord now at Yale (1640a ar in Grant O’Brien’s catalogue),4 was extremely small and completely outdated by 18th-century standards. It has a restricted compass, C–d′′′, and still has its original 8′ × 4′ disposition, without a second 8′ stop and with the registers projecting through the cheek instead of being connected to stop knobs on the nameboard (see illus.1).

Harpsichord by Andreas Ruckers the Elder (Antwerp, 1640; O’Brien 1640a ar); The Belle Skinner Collection, acc. no. 4878.1960 (courtesy of the Yale University Collection of Musical Instruments, New Haven, Connecticut; photo credit: Christopher Gardner)

In these two articles I will survey the plucked keyboard instruments that have been associated with Handel from the composer’s time to the present. The focus in Part I is on three surviving Ruckers harpsichords that were promoted as ‘Handel’s harpsichord’ in the 18th and 19th centuries. A good deal of new information about them has come to light as the result of the recent projects to digitize newspapers, journals and other 18th- and 19th-century documents.5 This has enabled me to trace their provenance in greater detail than before, and to place them in the context of the process of importing, modernizing and circulating instruments by the Ruckers-Couchet family of Antwerp in 18th-century England. Evidence has also come to light of three more Ruckers instruments said to have been owned and used by Handel or his followers, making six in all. Tracing the history of these instruments can help us to understand how they were used, and why these obsolete instruments might have been preferred to the larger and more modern ones by London makers such as Shudi and Kirkman.

In Part II (in the next issue of Early Music) I focus on the other plucked keyboard instruments said to have been owned by Handel: (1) a large harpsichord known from a design by Sir James Thornhill for its lid painting; (2) a harpsichord said to have been made by Burkat Shudi in 1729 and to have been given by Handel to the singer Anna Maria Strada; (3) the small harpsichord in Mercier’s portrait of the composer; (4) a large Shudi harpsichord with a 16′ stop advertised twice in the 1780s with the claim that it had belonged to Handel; and (5) a Hitchcock spinet said to have been given by Handel to the trumpeter and violinist Andrew George Lemon. Not all of the claims made for these eleven instruments stand up to scrutiny, as we shall see, but a surprising number of them can be traced back to Handel’s milieu, and I argue that the composer needed a large number of instruments for his varied activities as a composer, solo keyboard virtuoso, teacher and musical director. Part I therefore focuses on instruments he would have used in his oratorio seasons at Covent Garden, and Part II on those he would have used in the private sphere, at home in Brook Street.

Ruckers harpsichords in England

Sir John Hawkins wrote that ‘The harpsichords of the Ruckers have long been valued for the fullness and sweetness of their tone, but are at this time less in use than formerly, on account of the narrowness of their compass, compared with the modern ones’.6 Nevertheless, they were highly prized throughout the 18th century, enjoying a cachet equivalent to the roughly contemporary violins of the Amati family, particularly when enlarged and modernized in England in a process equivalent to the ravalement applied to Ruckers instruments in France and the Netherlands.7 So far I have found evidence of more than 90 Ruckers and Couchet instruments offered for sale in 18th-century Britain,8 with frequent references to their brilliant tone, their elaborate soundboard and case decoration, and occasionally to the fine Flemish paintings on their lids—which originally doubled the price.9 In 1884, when harpsichords had been out of general use for about 80 years and the modern revival had hardly begun,10 Puttick and Simpson featured 1623 ar, the two-manual 1623 harpsichord by Andreas Ruckers,11 in the sale of the music library of the composer and organist John Hullah.12 An advertisement emphasized that Ruckers harpsichords ‘have become very scarce’ and urged ‘Amateurs of old Key-board Instruments’ to ‘watch this opportunity to acquire a fine example of the best makers who, as a family, rivalled the great families of Cremona violin-makers’.13

Given the cachet Ruckers harpsichords enjoyed throughout the 18th century, it is hardly surprising that Handel was attracted to them. He was extremely status-conscious and usually had the income to acquire the best musical instruments, along with luxuries such as his extraordinary art collection, filled with Dutch and Flemish paintings, some from the same Antwerp milieu as the Ruckers instruments.14 Using harpsichords by an internationally famous brand went hand-in-hand with his art connoisseurship, which, as Thomas McGeary has put it, was ‘one facet of his naturalization and socialization as an English gentleman, and a way of joining with the interests of aristocrats, the gentry and the upper class of his adopted homeland’.15 In addition to their musical qualities, Ruckers harpsichords, like Dutch and Flemish paintings, were status symbols collected by a wide cross-section of the upper classes.

The earliest Ruckers harpsichord known to have been imported into England has a particular importance because we know a lot about it from correspondence between its first owner, Sir Francis Windebank (1582–1646), one of Charles I’s secretaries of state, and Balthasar Gerbier, the English resident at the Brussels court, who acted as a go-between with Joannes Ruckers in Antwerp.16 Windebank acquired it in 1639 after rejecting a double-manual harpsichord the previous year because of its short octave; he insisted on an instrument with a chromatic compass down to C, needed for English solo keyboard music and the continuo parts of ensemble music.17 Paula Woods suggested that this instrument survives today as 1639 ir, the Joannes Ruckers harpsichord now in the Victoria and Albert Museum.18 It was originally similar to 1640a ar, though with a chromatic compass C–d′′′ (1640a ar originally had a short octave), and was rebuilt with a second 8′ register in late 17th- or early 18th-century England.

The process of modernization was crucial to the continuing popularity of Ruckers harpsichords in England, as elsewhere in Europe, keeping them up to date with changing musical requirements. To summarize a complex situation, it typically involved combinations of four processes: changing the 1 × 8′, 1 × 4′ disposition to 2 × 8′; adding an extra register, making 2 × 8′, 1 × 4′; enlarging the compass and removing short octaves in the process; changing single-manuals into double-manuals; and in particular, turning transposing doubles (with the two keyboards usually a 4th apart) into aligned instruments with both keyboards at the same pitch. Counterfeit Ruckers harpsichords were also made to cater for the demand, sometimes with little or no genuine material. An unidentified early 18th-century English craftsman made ‘1634 ir’, the double- manual at Ham House in Richmond, inscribed ‘IOANNES RUCKERS ME FECIT ANTVERPIAE’ and dated 1634, and ‘1646 ar’, the single-manual at Helmingham Hall in Suffolk, inscribed ‘ANDREAS RUCKERS ME FECIT ANTWERPIAE’ and dated 1646, as well as the unattributed double-manual dated 1623, now in the Cobbe Collection at Hatchlands Park in Surrey.19

We know little at present about the process of importing Ruckers harpsichords into England, though it is likely that London’s immigrant instrument-makers used their contacts in France and the Netherlands to acquire them. On 18 April 1711 Peter Bressan from Bourg-en-Bresse in eastern France, the leading London recorder- and oboe-maker, included two ‘extraordinarily good Ruckers Harpsichords of Antwerp, each of them 2 Setts of Keys, approv’d of by the best Masters in England’ in an auction at his premises, Duchy House in Somerset House Yard.20 A number of London’s harpsichord-makers were also immigrants, and are therefore likely to have had contacts enabling them to locate and import Ruckers instruments. They include Joseph Tisseran, possibly a French Huguenot; Hermann Tabel from Amsterdam; Burkat Tschudi or Shudi from the canton of Glarus in Switzerland; Rutger or Roger Plenius from Amsterdam; and Jacob Kirchmann or Kirkman from Bischwiller in Alsace.21 Advertisements for an auction of Plenius’s bankrupt stock on 14 December 1756 included ‘one Harpsichord, by Ruckers, of Antwerp’,22 while A. J. Hipkins wrote that in 1772–3 Broadwood’s (the successor firm to Shudi’s) hired out Ruckers harpsichords to ‘the Duchess of Richmond, Lady Pembroke, Lady Catherine Murray, etc. etc.’.23 Broadwood’s still had two Ruckers harpsichords for hire until 1790 and 1792, when they were sold off to Lord Camden and a Mr Williams.24

At least twelve of the surviving Ruckers-family harpsichords accepted as authentic by Grant O’Brien seem to have been modernized in England, including 1639 ir (already discussed) and the three associated with Handel to be discussed later: 1612a hr, 1651b ar and 1640a ar.25 In nearly all cases it is unclear who carried out the work, though John Koster has recently argued that 1617 ir, originally a Joannes Ruckers transposing double, was modernized by the London harpsichord-maker and organ-builder John Crang around 1740–50.26 This instrument was perhaps the ‘EXCELLENT HARPSICHORD Made by RUCKER, a. d. 1617, well preserved, of a brilliant powerful Tone’ offered for sale in Bath in January 1788.27 A few advertisements mention that instruments had been modernized, as in March 1775 when the music publisher James Bremner offered a ‘Harpsichord, by Andrew Rucker … An exceeding fine-toned one, made Anno 1604, included in a new Mahogany Case, with a new Set of Keys, Buff Stop and Pedal, by Schudi’;28 or when George Downing, announcing himself in December 1777 as a dealer in second-hand harpsichords, offered ‘an excellent one by Couchett, and another by Rucker, both made at Antwerp; one in 1634; the other in 1638’.29 He added that they had both been ‘substantially repaired by Messrs. Kirkmans’. Interestingly, virtually none of the many dated Ruckers harpsichords mentioned in 18th-century advertisements seem to match instruments surviving today.

Handel would have come across at least two Ruckers instruments early in his career in England. ‘A Rucker’s Virginal, thought to be the best in Europe’ was in the collection of the musical coal merchant Thomas Britton, sold after his death in 1714.30 Sir John Hawkins, who printed the sale catalogue and provided most of the known information about Britton’s famous concerts in the ‘very long and narrow’ concert room above his warehouse in Clerkenwell, wrote that ‘Dr. Pepusch, and frequently Mr. Handel, played the harpsichord’ in them.31 However, a Ruckers virginal is unlikely to have been more than an antique curiosity to Handel. To judge from 18th-century advertisements, English interest in Ruckers instruments was focused almost entirely on their harpsichords: the only other unambiguous references to virginals or spinets so far discovered are to ‘AN undoubted OCTAVE SPINNET of James [sic] Ruckers, of a fine brilliant Tone, and well preserved’ offered for 10 guineas in December 1751,32 and ‘a good-toned Virginal by Rucker’ auctioned on 29 December 1777.33

Handel would have encountered a remarkable Ruckers instrument a few years after Britton’s death, at Cannons, the country estate of James Brydges, Earl of Carnarvon (later Duke of Chandos), where he worked for a few years from 1717. According to the catalogue of the duke’s instruments drawn up in 1720, pride of place among those at Cannons (listed second, after the Abraham Jordan organ in the chapel) was given to ‘A four square Harpsicord with two Rows of Keys at one End and a Spinet on the side made at Antwerp by John Ruckers, the Lid is painted and represents the Mount Parnassus with the nine Muses and Minerva coming to instruct them, painted by A Tilens in the year 1625’.34 At the Cannons sale in 1747 prior to the building’s demolition it was in the duke’s study, valued at £31 10s.35 It may have been acquired at that time by J. C. Pepusch, the former musical director at Cannons, if it can be identified with the ‘Fine-toned Rucker Harpsichord and Virginal, formerly in the possession of the celebrated Dr. PEPUSCH’ advertised by the auctioneer James Christie in May 1785.36 It was offered twice more in June 1785,37 and was presumably the ‘curious double key’d Harpsichord, with a Virginal, made by Rucke’ advertised in June 1787 by the music-seller George Smart, father of Sir George Smart.38 It does not seem to survive today.

The Cannons instrument was an example of the most elaborate and expensive model made by members of the Ruckers family, a double-manual harpsichord with a virginal incorporated in its case and a valuable Flemish painting on the inside of the lid.39 Assuming that the harpsichord part had been modernized with the keyboard aligned and the compass extended, Handel might have used it to play the solo music he seems to have written at Cannons, including one or two of the pieces conceived specifically for a double-manual harpsichord, hwv466, 470, 485 and 579.40 However, there were other two-manual harpsichords at Cannons, including one by Hermann Tabel,41 and these would doubtless have been more compact and convenient for directing the major works he wrote there—including the first versions of Acis and Galatea (June 1718) and Esther (probably summer 1720).42

Ruckers harpsichords and Handel’s oratorio seasons

We now turn to the various Ruckers harpsichords said to have belonged to Handel. I will argue that they were mostly acquired and used by him and his successors in the Lenten oratorio seasons at Covent Garden. Handel’s loss of sight required his assistant John Christopher Smith to take over their direction starting from the 1753 season, or perhaps a little earlier, leaving the composer just playing organ concertos between the acts.43 Smith (1712–95; illus.2), continued the Covent Garden seasons after Handel’s death, going into partnership with John Stanley (1712–86) with a similar arrangement, Smith mostly directing the oratorios and Stanley playing organ concertos. They moved the operation to Drury Lane in 1770, and Smith retired after the 1774 season, leaving Stanley to struggle on alone in 1775. Stanley went into partnership with Thomas Linley senior the next year, which lasted until shortly before Stanley’s death in 1786.

Johann Zoffany, John Christopher Smith (c.1763) (© Gerald Coke Handel Foundation)

J. C. Smith’s activities are central to understanding how, when and why Handel acquired his Ruckers harpsichords, and the crucial piece of evidence is the bequest in Handel’s will, written on 1 June 1750: ‘I give and bequeath to Mr Christopher Smith [Senior deleted] my large Harpsicord, my little House Organ, my Musick Books, and five hundred Pounds Sterl<ing>’ (illus.3).44 Christopher Smith (1683–1763) was J. C. Smith’s father and Handel’s principal music copyist.45 In turn, Smith senior bequeathed at least some of these items to his son in his own will, made on 16 December 1762 and proved on 10 January 1763: ‘All my Musick Books and Pieces of Musick whether Manuscript or otherwise which were left to me in & by the last Will & Testament of my Friend George Frederick Handel deceased’, as well as ‘all my other Musick & Books of Musick both in print and manuscript and all my Instruments of Musick which I shall be possessed of at the time of my decease’.46 Musical instruments are not mentioned in J. C. Smith’s own will, made on 13 May 1786.47

The first page of Handel’s will, 1 June 1750, from the copy in the Gerald Coke Handel Collection (© Gerald Coke Handel Foundation)

Whether ‘all my Instruments of Musick’ included Handel’s ‘large Harpsicord’ and his ‘little House Organ’ is not clear, and nothing more was heard of the organ, though the harpsichord in Handel’s will has traditionally been identified with two Ruckers harpsichords to be discussed shortly: 1612a hr, in the Royal Collection, and 1651b ar, now in the Victoria and Albert Museum. However, it is unlikely that Handel (or anyone else at the time) would have thought of them as ‘my large Harpsicord’, and the situation is complicated by a number of other candidates, including three other Ruckers harpsichords mentioned in 18th-century documents but not readily identifiable with surviving instruments, to say nothing of a Shudi harpsichord that must have been very large, to be discussed in Part II.

The first Ruckers offered for sale as Handel’s harpsichord appeared in an announcement for a benefit concert on 9 March 1769 given by the violinist Gaetano Pugnani at Almack’s Great Room in King Street, St James’s.48 At the bottom of the announcement is the sentence: ‘And at Mr. Pugnani’s is to be sold, an Harpsichord of J. Rucker, of the late Mr. Handel’s’. Pugnani gave his address as ‘Mr. Lombardi’s, Operator for the Teeth, in the Haymarket’. He was leader of the opera orchestra at the nearby King’s Theatre and was to go back to Italy at the end of that season.49 He was presumably disposing of his Ruckers harpsichord before his departure.

A second Ruckers harpsichord associated with Handel was sold six years later, in an auction at Christie’s Great Room in Pall Mall in April 1775: ‘THAT much-admired double key’d HARPSICHORD, by RUCKER, remarkable for its fine Tone, and keeping well in Tune; which Mr. Handel performed upon in his Oratorios, and has ever since his Time been used for that Purpose by Mess. Stanley and Smith’.50 The date of this sale, Saturday 8 April 1775, may be significant because the Drury Lane oratorio season had ended the day before.51 As already mentioned, after J. C. Smith retired in 1774 John Stanley ran the 1775 season alone. This turned out to be financially disastrous, mainly because of direct competition from J. C. Bach and Abel at the King’s Theatre, to the extent that Stanley was unable to pay his musicians in full and had to be bailed out by David Garrick.52 Thus it may be that, in an hour of need, Stanley was forced to sell his prized harpsichord with its Handel associations.

So far as is known, this instrument does not survive, or cannot readily be identified with any surviving two-manual Ruckers. However, John Stanley either acquired another Ruckers after 1775 or had more than one all along, for ‘A remarkable full-toned single-keyed ditto [harpsichord], undoubted, by O. Rucker and leather cover’ appeared in the auction of his effects, held by Christie’s on 24 June 1786.53 ‘O. Rucker’ seems to have been Christie’s shorthand for ‘old Rucker’—that is Hans Ruckers rather than his sons Joannes and Andreas. In the advertisements for the sale it is listed as ‘an UNDOUBTED SINGULAR FULL TONED ditto [harpsichord], by old RUCKER’.54 Christie used the same formula in February 1775 when advertising a ‘Harpsichord by O. Rucker, of peculiar excellence’.55 It is unclear whether Stanley’s Ruckers was also one of those that had been used by Handel.

The Royal Ruckers

The best known of the three surviving harpsichords associated with Handel is 1612a hr (illus.4), the 1612 Joannes Ruckers in the Royal Collection, now on loan to the Benton Fletcher Collection at Fenton House in London.56 It is an English 18th-century modernization of a double-manual harpsichord, shown by O’Brien to be the unique surviving example of an instrument originally made with keyboards pitched a tone apart.57 Its later provenance is worth setting out in detail because it has often been doubted that it was owned by J. C. Smith and should therefore be considered as a possible Handel harpsichord.58

Harpsichord by Johannes Ruckers (Antwerp, 1612; O’Brien 1612a hr), The Royal Collection, rcin 69028; on loan to the Benton Fletcher Collection, Fenton House, Hampstead (The Royal Collection Trust, © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, 2021)

In 1776 Hawkins mentioned, as an illustration of Handel’s single-minded devotion to his art, that the composer ‘had a favourite Rucker harpsichord, the keys whereof, by incessant practice, were hollowed like the bowl of a spoon’.59 This striking feature was also mentioned in the anonymous biography of J. C. Smith, apparently by the Rev William Coxe,60 Smith’s stepson, which stated that his stepfather had presented the harpsichord, ‘so remarkable for the ivory being indented by Handel’s continuous exertions’ to George III, together with ‘the rich legacy which Handel had left him, of all his manuscript music, in score’.61

We do not know exactly when this presentation took place, but it was presumably between the end of the 1774 oratorio season at Drury Lane, when Smith retired to Bath,62 and 7 November 1784, when George III referred to a list of the Handel manuscripts in a letter to Mrs Delany.63 This list was printed the next year in Charles Burney’s book about the Handel Commemoration.64 The Handel manuscripts remained in London and were eventually housed at Buckingham Palace,65 but William Coxe wrote that George III sent the harpsichord to Windsor Castle together with the bust of Handel by Louis-François Roubillac, which the king had also received from Smith.66 They may both have been placed in the Music Room at Windsor, created in 1794.67

1612a hr was seen at Windsor a number of times in the early 19th century by those reporting on George III’s madness. There are descriptions of the king playing a harpsichord at Windsor in 1811, 1812 and 1814,68 and one report in 1811, printing ‘A letter from Windsor’, specifically stated that ‘the harpsichord on which his Majesty plays, formerly belonged to the great Handel, and is supposed to have been manufactured at Antwerp in the year 1612’.69 It was said to be in the king’s sitting room in the Blenheim Tower. Another report mentioned that the king used ‘to shew it to his musical friends with much pleasure, and explain to them whom it belonged to, and that the keys were worn away by HANDEL’s fingers’,70 which confirms that 1612a hr was the instrument given by J. C. Smith to George III. Inscriptions stamped on its bottom boards, ‘V[ictoria] R[egina], 866, Windsor Castle, Room 528’, confirm its location as the Grand Vestibule at Windsor Castle during Queen Victoria’s reign.71

In 1883 A. J. Hipkins, a manager at Broadwood’s and at the time Britain’s leading authority on early keyboard instruments,72 saw 1612a hr at Windsor, reporting that it had recently been discovered ‘with some old sedan chairs, in an almost forgotten store-room’ and that ‘some of the ivory of the keys’ had been ‘detached and purloined’.73 However, those keys were not the original hollowed-out ones: Hipkins stated that it had ‘two modern sets’, adding: ‘with new strings and jacks and some necessary repairs I believe this instrument could be made playable again, were it placed in skilled hands’. He evidently arranged for that to happen, writing in 1893 that ‘The keyboards were again renewed by Messrs. Broadwood’ before being exhibited at the 1885 Inventions Exhibition.74 It was lent to the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1912 and to the Benton Fletcher Collection in the 1940s, being transferred with it to Fenton House in 1952.75 It was restored three times in the 20th century, and is now a strange hybrid. It has its original decorated soundboard and rose; a largely 18th-century case and lid but with a modern lacquer finish; late 19th-century keyboards; a stand reportedly adapted from one made for a square piano;76 and modern copies of original Ruckers decorative papers in the keywell.

The Winchester Ruckers

The second surviving Ruckers harpsichord associated with Handel is 1651b ar (illus.5), the double-manual instrument now in the Victoria and Albert Museum.77 This is another example of an early 18th-century English modernization and enlargement, in this case carried out on a single-manual instrument originally similar to 1640a ar. It has traditionally been dated on the basis of the inscription ‘ANDREAS RUCKERS ME FECIT ANTWERPIAE 1651’, but Sheridan Germann argued that its soundboard painting and other decoration suggest that it was made about 20 years earlier, and that the date might originally have read ‘1631’.78

Harpsichord by Andreas Ruckers the Elder (Antwerp, 1631 or 1651; O’Brien 1651b ar); V&A, 1079–1868 (© Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

The 1651 (or 1631) Ruckers was acquired by Broadwood’s in Winchester in 1852 and was promoted by them as Handel’s harpsichord, notably in the historical recitals given by Charles Salaman in London in 1855.79 An article about Broadwood’s published three years later mentioned that ‘Handel’s favourite harpsichord’ could be seen at their premises in Great Pulteney Street.80 By the time they presented it to the South Kensington Museum in 1868 it was no longer playable, as they made clear in a covering letter dated 18 November that year, probably written by Hipkins or under his direction.81 The letter set out the instrument’s Handelian credentials and described its current state, pointing out among other things that the keyboards were ‘undoubtedly modern’; that it was ‘not now capable of being tuned’; and that ‘any attempt to improve the accord of it might prove disastrous by the sounding-board giving way altogether’; ‘tuning should not be attempted’. Broadwood’s also supplied a letter from George William Chard (1765–1849), organist of Winchester Cathedral,82 to the Rev George Coxe (1758–1844), Rector of St Michael’s, Winchester, younger brother of William Coxe, and also therefore a stepson of J. C. Smith.83 George Coxe responded by certifying the correctness of Chard’s letter ‘As far as my knowledge goes’, dating it ‘Twyford [the village south of Winchester], May 13th, 1842’.

To summarize Chard’s letter to George Cox: he asserted that the instrument was Handel’s ‘favourite fine double-keyed harpsichord’; that the composer had presented it to J. C. Smith; that it was the instrument ‘you have heard repeatedly Mr. Schmidt play on’; that on Smith’s death in 1795 it ‘came into the hands … of the Dowager Lady Rivers’ (Lady Martha Rivers Gay (1749–1835), George Coxe’s sister, who lived in Winchester);84 and that it was then successively owned by three Winchester worthies: ‘Mr. Wickham, surgeon’, presumably William John Wickham (d.1864);85 ‘the Rev. Mr. Hawtry, Prebendary of Winchester Cathedral’, that is Prebendary John Hawtrey (d.1817);86 and Chard himself ‘in whose possession it still remains’. Chard died in 1849, and Broadwood’s stated that they had purchased the harpsichord in 1852 from ‘Mr. Hooper, a piano-forte tuner at Winchester’.

The flaw in all this, as Hipkins realized, is that tracing the history of 1651b ar back to J. C. Smith does not prove that it came from Handel, despite Chard’s assertion to that effect. Indeed, Hipkins was clearly aware that 1612a hr had the better claim, writing that ‘Handel’s large harpsichord did not go to Winchester, but to Windsor’.87 As he pointed out, the Winchester Ruckers is ‘a rather small harpsichord’; it is only 2,020mm by 915mm. It certainly could not be described as Handel’s ‘large Harpsicord’, though it might have been another instrument used by the composer and/or J. C. Smith at Covent Garden.

The Twining Ruckers

A third surviving Ruckers harpsichord associated with Handel is 1640a ar (illus.1), the single-manual Andreas Ruckers now at Yale. Although not so well known as the other two, this instrument has a reasonably convincing connection with Handel, with a provenance reaching back at least to the early 1760s. It is first mentioned in a letter of 31 January 1774 written by the Rev Thomas Twining (1735–1804) to his friend Charles Burney. Thomas Twining, son of the tea trader Daniel Twining, was curate of Fordham near Colchester (and later rector of St Mary at the Walls in Colchester), a Classical scholar and accomplished amateur musician.88 He wrote to Burney about purchasing a new Pohlmann piano, describing his harpsichords in the process:

I have hitherto made shift with a little Andrew Ruckers; but the want of compass is miserable. The tone is very fine in the middle, & has a certain silver crispness (I cannot help my own ideas!) that is not in any other harpsichord that I know of. But the sweetness, the equality & the firm bases of Kirkman’s are far beyond. I have likewise a 2 Unis<on> Kirkman which was Mrs. T[wining]’s, & has hitherto stood at Colchester. This I shall carry to Fordham, & sell my Ruckers if I can get anything for it. Do you know any body I could impose upon? It was the very harpsichord that Handel used for some years at Covent Garden: I think my father bought it of Kirkman—Shudi—I don’t know which. Seriously, pray tell me what is the best way of parting with it, & what I may reasonably expect to get for it.89

Twining mentioned Burney’s reply (now apparently lost) in his next letter, on 7 March:

Thank you for your opinion about my Ruckers. Here is fresh exercise for my patience. If any fool would give me but 18 guineas for it, I think I should be easy. Why, Sir, the mere curiosity of the stops coming strait out at the sides, as they did in Jubal’s harpsichord, if he made any, is worth the money. (I should like to rub out the name & date, & put it in an auction as a Jubal.)90

In the event, Twining did not sell his Ruckers. It is not mentioned specifically in his will,91 but A. J. Hipkins, outlining its provenance up to 1893,92 stated that it passed to his nephew Richard (1772–1857),93 also a member of the tea-trading firm, and then to Richard’s daughter Elizabeth (1805–89), a botanical artist.94 Elizabeth Twining lent it to the exhibition of ‘ancient musical instruments’ organized by Carl Engel at South Kensington in 1872, when it was said that it ‘once belonged to the celebrated composer Handel, and was used by him in composing his Oratorios’.95 According to Hipkins, Elizabeth bequeathed the harpsichord to her niece Agnes Emily, the wife of the artist Andrew Brown Donaldson.96 It was next owned by Sir Algernon Oliphant, who must have acquired it after Agnes Donaldson’s death in 1918 or her husband’s the following year. Hipkins stated that it was ‘an unrestored Andrew Ruckers single keyboard harpsichord, dated 1640’, which identifies it securely with 1640a ar, now in the Belle Skinner Collection at Yale University.97 Oliphant’s collection was auctioned in New York in April 1922, which is when Skinner acquired it.98

By the 1770s Twining’s Ruckers must have seemed like an antique. He complained about its miserable ‘want of compass’; it is now C–d′′′, the result of what O’Brien calls ‘a conservative petit ravalement’, probably in England around 1700, but was originally C/E–c′′′ with a short octave. Twining made fun of the fact that it retained the original arrangement with the registers projecting through the cheek, likening it to a harpsichord that might have been made by Jubal, the musician in Genesis. It is remarkable, however, that Twining did not complain that his Ruckers retained its original disposition of 1 × 4′, 1 × 8′, standard in the 16th century but completely outmoded by the 1770s.99

We might think that Handel would have had no use for such an obsolete instrument, but Twining told Burney that it was ‘the very harpsichord that Handel used for some years at Covent Garden’, meaning that the composer used it for the direction of oratorios, not to play solo music. Its small compass would not have mattered had it been used just for continuo playing. Twining also stated that his father Daniel (1713–62) had purchased the harpsichord from Kirkman’s or Shudi’s, and the obvious moment for this to have happened was after Handel’s death in 1759, when Smith might understandably have wanted to replace it with a more modern instrument. Thomas was Daniel’s eldest son and the most obviously musical member of the family, so it is likely that his family’s Ruckers was passed on to him at or before his father’s death.

This, however, does not explain why Handel might have wanted to acquire such an instrument. An obvious answer is that he valued it for its sound; as Twining put it: ‘The tone is very fine in the middle, & has a certain silver crispness … that is not in any other harpsichord that I know of’. Similar things were often said of Ruckers harpsichords at the time, as today. In February 1729 the auctioneer Christopher Cock advertised ‘a Harpsicord of the Silver Tone, by the famous Hans Ruckers’,100 while Christie’s included ‘a brilliant fine-ton’d HARPSICHORD by JOHN RUCKERS of ANTWERP’ in an auction on 11 and 12 March 1772.101 Three years before, in February 1769, Christie’s had advertised ‘An HARPSICHORD by Rooker of Antwerp, ESTEEMED by the most eminent Masters to have the finest Tone of any in England, in it’s original Case, as finished by Rooker, and fuller Compass than most of his making’.102 Its value was emphasized: ‘To prevent Trouble, the lowest Price is Eighty Guineas’. Sweetness of tone was sometimes specifically mentioned, as in February 1791, when the Repository at 115 Great Portland Street advertised ‘a real Rucker Harpsichord, very sweet tone, with a pedal for double bass occasionally’.103 As already mentioned, Hawkins wrote that Ruckers harpsichords had ‘long been valued for the fullness and sweetness of their tone’.

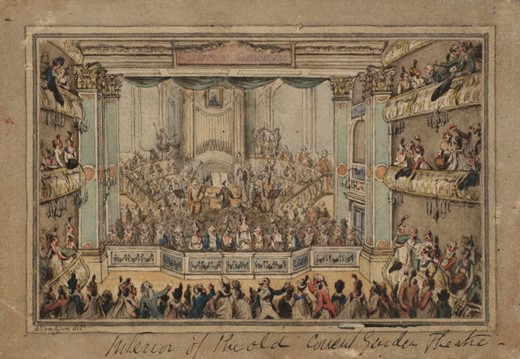

Another reason why Handel might have valued 1640a ar in particular was its extremely small size. It is only 1,813mm by 708mm, yet it has a powerful and brilliant sound to judge from recordings,104 and this would have been a real asset in a cramped performing area. In the 1740s Handel performed oratorios with everyone on the stage of the theatre. The evidence, sketchy for his time but more abundant for that of his successors, suggests that he sat at a harpsichord in the middle of the performing area which was connected by a ‘long movement’ of trackers to a large organ at the back.105 There was no need to connect the two instruments: the harpsichord (later a piano) was evidently placed on a special stand that incorporated an organ console with a projecting keyboard, producing a two- or three-manual composite harpsichord-organ, with the lowest keyboard connected to the organ. Handel used the harpsichord to accompany the arias and recitatives of oratorios and the organ mainly for the choruses. All of his singers stood at the front, his continuo players were grouped around him and the remaining members of the orchestra were placed in tiers rising at the sides. A watercolour of an oratorio performance at Covent Garden between 1792 and 1803 certainly suggests that space was at a premium (illus.6).106

Benedict Anthony van Assen, Interior of the Old Covent Garden Theatre; V&A, s. 19–1997, detail (© Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

Conclusion

We can now see that Handel was not unusual in 18th-century England in his preference for Ruckers harpsichords: they were simply thought to be the best instruments, equivalent to Amati violins. Handel, J. C. Smith and Stanley were clearly prepared to use small instruments with a restricted compass, though most of them would have been enlarged and modernized to a lesser or greater extent; Twining’s 1640a ar must have been one of the least modified Ruckers in use in England at the time. Handel and his followers seem not to have used them to play solos, since keyboard concertos between the acts of oratorios were played on the organ. As continuo instruments, however, their small size and brilliant tone—what we might call an advantageous power to size ratio—would have been real assets in a crowded performing area. All a continuo player needed was an instrument with chromatic bass down to C, and even 1640a ar provides that.

We can now identify six Ruckers harpsichords with some claim to have been owned and used by Handel and/or his followers. Three are known only from 18th-century documents: (1) the Joannes Ruckers instrument sold by Pugnani in 1769; (2) the double-manual sold by Christies in 1775, perhaps for John Stanley; and (3) the single-manual in the sale of Stanley’s effects in 1786. Then there are three surviving instruments: (4) the Royal Ruckers 1612a hr, with a convincing provenance back to J. C. Smith; (5) the Winchester two-manual Andreas Ruckers 1651b ar, also with a reasonably convincing provenance back to Smith; and last but not least (6) the little Andreas Ruckers single-manual 1640a ar, perhaps acquired by Daniel Twining from Handel’s estate shortly after the composer’s death, and in the Twining family’s possession until the 20th century.

Why would Handel and his followers have needed so many Ruckers harpsichords? It is easy to imagine that these relatively light and delicate instruments, without the massive oak spines of Kirkmans and Shudis, would have been easily damaged in the hurly-burly of oratorio seasons. This would have involved clearing the stage after each Wednesday and Friday performance to allow for the theatre to be reclaimed by the separate company that put on ordinary spoken plays the rest of the week, doubtless often leaving keyboard instruments vulnerable behind the scenes. Even without damage, they probably wore out quite quickly, and it may be that the oratorio managers found it easier to dispose of them and acquire replacements second-hand rather than expend time and trouble on having them repaired.

None of these Ruckers instruments could credibly have been the large harpsichord that Handel left to Christopher Smith in his will. In Part II of this article I will discuss the evidence that Handel did own at least two harpsichords much larger than 1612a hr, the largest of the three surviving Ruckers associated with Handel. I will also argue that 1612a hr, reportedly left by Handel with its famous keyboard ‘hollowed like the bowl of a spoon’ by ‘incessant practice’, was not used in oratorios, but was kept by Handel at his house in Brook Street.

Peter Holman, Emeritus Professor at the University of Leeds, has wide interests in English music from about 1550 to 1850, performance practice and the history of instruments and instrumental music. His most recent book, Before the baton: musical direction and conducting in Stuart and Georgian Britain, was published by Boydell in February 2020. As a performer he is director of The Parley of Instruments, the Suffolk Villages Festival, and Leeds Baroque.

I am particularly grateful to Thomas McGeary for his characteristically detailed and thoughtful responses to drafts of this article, and to John Koster for much useful information and advice. I must also thank Donald Burrows, Michael Cole, Dominic Gwynn, John Greenacombe, Chris Gutteridge, Katherine Hogg, David Hunter, Jenny Nex, Gabriele Rossi Rognoni, Luke Shackell, Susan Sloman, Barbara Small, Michael Talbot, Rebecca Virag and Lance Whitehead for reading drafts and/or for help of various kinds. These articles were written in 2020 during the coronavirus pandemic when libraries and museums were closed, and for this reason some research avenues remain to be explored.

Footnotes

See A. J. Hipkins, ‘Handel’s harpsichords’, Athenaeum, no.2917 (22 September 1883), pp.378–9; Hipkins, ‘Handel’s harpsichords’, The Musical Times, special Handel supplement (14 December 1893), pp.30–33; R. Russell, The harpsichord and clavichord: an introductory study (London, 1959), pp.165–8; Handel: a celebration of his life and times 1685–1759, ed. J. Simon (London, 1985), pp.175–6; T. Best, ‘Handel and the keyboard’, in The Cambridge companion to Handel, ed. D. Burrows (Cambridge, 1997), pp.208–23, at pp.222–3; Best, ‘George Frideric (Frederick) Handel’, in The harpsichord and clavichord, an encyclopedia, ed. I. Kipnis (New York and Abingdon, 2/2015), pp.216–18; R. L. Marshall, ‘Bach, Handel and the harpsichord’, in The Cambridge companion to the harpsichord, ed. M. Kroll (Cambridge, 2019), pp.263–98, at pp.265–6. See also G. O’Brien, ‘The double-manual harpsichord by Francis Coston, London, c.1725’, Galpin Society Journal, xlvii (1994), pp.2–32, at pp.19–26.

For harpsichords associated with Bach, see Marshall, ‘Bach, Handel and the harpsichord’, esp. pp.266–8 and the literature cited there. For keyboard instruments associated with Mozart, see esp. R. Maunder, ‘Mozart’s keyboard instruments’, Early Music, xx/2 (1992), pp.207–19; Maunder, Keyboard instruments in eighteenth-century Vienna (Oxford, 1998).

G. O’Brien, Ruckers: a harpsichord and virginal building tradition (Cambridge, 2/2008), esp. pp.218–35; J. Koster, ‘The musical uses of Ruckers harpsichords’, in The golden age of Flemish harpsichord making, ed. P. Vandervellen (Brussels, 2017), pp.50–69, 399–404; Koster, ‘The harpsichord of the virginalists’, in Aspects of English keyboard music before c.1630, ed. D. J. Smith (Abingdon and New York, 2019), pp.29–48.

O’Brien, Ruckers, p.266; see also D. H. Boalch, rev. C. Mould, Makers of the harpsichord and clavichord 1440–1840 (Oxford, 3/1995), p.561.

Principally British Periodicals, https://www.proquest.com/products-services/british_periodicals.html; Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Burney Newspapers Collection, https://www.gale.com/intl/c/17th-and-18th-century-burney-newspapers-collection; British Library Newspapers, part I: 1800–1900, https://www.gale.com/intl/c/british-library-newspapers-part-i; The British Newspaper Archivehttps://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/.

Sir John Hawkins, A general history of the science and practice of music, 5 vols. (London, 1776), repr. in 2 vols. (London, 2/1853; repr. New York, 1963), ii, p.627.

See esp. O’Brien, Ruckers, pp.231–5; J. Koster, ‘Ravalement’, in The harpsichord and clavichord, ed. Kipnis, pp.394–5.

I will set out the new documentary material in full in ‘“Long valued for the fullness and sweetness of their tone”: 250 years of Ruckers harpsichords in Britain’, forthcoming in the Galpin Society Journal.

S. Germann, ‘Decoration’, in The harpsichord and clavichord, ed. Kipnis, pp.115–46, at p.127.

See P. Holman, ‘The harpsichord in nineteenth-century Britain’, Harpsichord & Fortepiano, xxiv/2 (Spring 2020), pp.4–14.

O’Brien, Ruckers, pp.260–61; Makers of the harpsichord and clavichord, pp.555–6.

For the sale, on 25 June 1884, see Athenaeum, no.2956 (21 June 1884), p.778; Musical Opinion, vii (July 1884), p.473; A. Hyatt King, Some British collectors of music (Cambridge, 1963), pp.54, 139.

Athenaeum, no.2952 (24 May 1884), p.651.

For Handel’s income and wealth, see esp. D. Hunter, The lives of George Frideric Handel (Woodbridge, 2015), pp.197–207. For his art collection, see T. McGeary, ‘Handel as art collector: art, connoisseurship and taste in Hanoverian Britain’, Early Music, xxxvii/4 (2009), pp.533–74.

McGeary, ‘Handel as art collector’, p.565.

P. Woods, ‘The Gerbier–Windebank correspondence: two Ruckers harpsichords in England’, Galpin Society Journal, liv (2001), pp.76–89. Four of the 14 documents were published in William N. Sainsbury, Original unpublished papers illustrative of the life of Sir Peter Paul Rubens as an artist and a diplomatist (London, 1859), pp.208–10, and were used by Hipkins in his remarkable article ‘Ruckers’, published in 1883 in A dictionary of music and musicians, ed. George Grove, 4 vols. (London, 1878–90), iii, pp.193–9, at p.196; it was reprinted after Hipkins’s death in 1903, with corrections and additions by Edith Hipkins and J. A. Fuller-Maitland, in Grove’s dictionary of music and musicians, ed. Fuller-Maitland, 5 vols. (London, 2/1904–10), iii, pp.180–9.

See esp. Koster, ‘The harpsichord of the virginalists’, pp.35–40.

Woods, ‘The Gerbier–Windebank correspondence’, pp.86–8, an identification accepted in Koster, ‘The harpsichord of the virginalists’, p.40. For the instrument, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, no.1739–1869, see O’Brien, Ruckers, p.253; also Makers of the harpsichord and clavichord, p.592; Catalogue of musical instruments in the Victoria and Albert Museum, Part 1: Keyboard instruments, comp. H. Schott (London, 2/1985), pp.57–8, quoted at https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O169594/harpsichord-ruckers-ioannes/ (accessed 22 January 2021). I will discuss its provenance in ‘“Long valued for the fullness and sweetness of their tone”: 250 years of Ruckers harpsichords in Britain’.

For these instruments see esp. O’Brien, Ruckers, pp.281, 283; C. Nobbs, ‘Counterfeiter and innovator: the maker of the Ham House harpsichord’, in Ham House: 400 years of collecting and patronage, ed. C. Rowell (New Haven, 2013), pp.337–47, 508–9.

Spectator, 17 April 1711; Daily Courant, 18 April 1711. For Bressan, see A biographical dictionary of English court musicians 1485–1714, compiled by A. Ashbee and D. Lasocki et al., 2 vols. (Aldershot, 1998), i, pp.187–91.

For these makers, see esp. Makers of the harpsichord and clavichord, pp.103–8, 147–8, 173–7, 188–9, 193. For evidence that Tabel came from Amsterdam rather than Antwerp as is traditionally said, see C. Mould, P. Mole and T. Strange, Jacob Kirkman, harpsichord maker to her Majesty (Ellesmere, 2016), pp.9, 42–4; M. Cole, Michael’s Blog: Square Pianos, 8 August 2017, https://www.squarepianos.com/blog-2017b.html (accessed 22 January 2021).

Public Advertiser, 8 December 1756; Gazeteer and New Daily Advertiser, 11 December 1756. See also L. Whitehead and J. Nex, supplementary material to ‘The insurance of musical London and the Sun Fire Office 1710–1779’, Galpin Society Journal, lxvii (2014), p.255, http://www.galpinsociety.org/supplementary%20material.htm (accessed 22 January 2021).

Hipkins, ‘Ruckers’, p.193.

W. Dale, Tschudi the harpsichord maker (London, 1913), p.72; C. Mould, ‘The Broadwood books’, English Harpsichord Magazine, i/1, 2 (1974), pp.[1–10, at p.4] http://www.harpsichord.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Broadwood.pdf (accessed 22 January 2021).

The others are 1617 ir, 1637a ir, 1609 ar, 1614 ar, 1623 ar, 1639b ar and 1645 ic; see O’Brien, Ruckers, pp.245, 251–2, 255–6, 257–8, 260–61, 265–6, 269–70, 271. I am grateful to John Koster for alerting me to ‘1636a ir’, now at Holyroodhouse in Edinburgh. It is described in O’Brien, Ruckers, pp.281, as ‘a large French double-manual harpsichord’, though it has been suggested that it was made as a counterfeit Ruckers in Amsterdam around 1680 and was imported to England around 1715, where it was provided with its stand; see the Royal Collection Trust website at https://www.rct.uk/collection/27934/harpsichord (accessed 22 January 2021).

I am grateful to John Koster for letting me see his unpublished report on this instrument, formerly the property of Dr Robert Johnson of Los Angeles. For Crang, see Makers of the harpsichord and clavichord, pp.39, 278–9; Whitehead and Nex, supplementary material to ‘The Insurance of Musical London’, pp.82–3.

Bath Chronicle, 10 January 1788.

Public Advertiser, 8 March 1775.

Morning Chronicle, 1 December 1777. Downing must have made an error reporting the date of the 1634 instrument or attributing it to ‘Couchett’ since Joannes I Couchet (1615–55), the nephew of Johannes Ruckers, only entered the Guild of St Luke in Antwerp as a master harpsichord-builder in 1642 or 1643; see Makers of the harpsichord and clavichord, p.37. For Downing, see Whitehead and Nex, supplementary material to ‘The Insurance of Musical London’, p.101.

Hawkins, A general history, ii, p.793.

Hawkins, A general history, ii, p.790. For Britton, see also C. Price, ‘The Small-Coal cult’, The Musical Times, cxix (1978), pp.1032–4; George Frideric Handel: collected documents, 4 vols., ed. D. Burrows, H. Coffey, J. Greenacombe and A. Hicks (Cambridge, 2013, 2015, 2019, 2020), i, p.297.

London Daily Advertiser, 11 December 1751.

Daily Advertiser, 25 December 1777.

George Frideric Handel: collected documents, i. 499; see also Handel: a celebration of his life and times, ed. Simon, pp.282–3. ‘A Tilens’ was presumably an error for the Antwerp painter Jan Tilens (1589–1630).

Handel: A celebration of his life and times, ed. Simon, p.105.

Morning Post, 18 May 1785.

Morning Herald, 3 June 1785; Public Advertiser, 9 June 1785.

World, 23 June 1787. For Smart, see C. Humphries and W. C. Smith, Music publishing in the British Isles from the beginning until the middle of the nineteenth century (Oxford, 2/1970), p.294; D. J. Golby, ‘George Smart’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

O’Brien, Ruckers, p.45. It does not seem to correspond to the sole surviving instrument of this type, the much-altered 1619 ir now in Brussels; see O’Brien, Ruckers, pp.246–7.

See esp. T. Best, ‘Handel’s harpsichord music: a checklist’, Music in eighteenth-century England: essays in memory of Charles Cudworth, ed. C. Hogwood and R. Luckett (Cambridge, 1983), pp.171–87; O’Brien, ‘The double-manual harpsichord by Francis Coston’, pp.23–4; Best, ‘Handel and the keyboard’, pp.216–17.

For Tabel’s one surviving harpsichord, see C. Mould, ‘The Tabel harpsichord’, in Keyboard instruments: studies in keyboard organology 1500–1800, ed. E. M. Ripin (New York, 2/1977), pp.59–65, illuss.46–52; Makers of the harpsichord and clavichord, p.650; Mould, Mole and Strange, Jacob Kirkman, pp.70–77.

See esp. J. Butt, notes for Acis and Galateahwv49a: Original Cannons Performing Version (1718), Dunedin Consort and Players / Butt, Linn ckd 319 (2008); J. Roberts, ‘The composition of Handel’s Esther, 1718–1720’, Händel-Jahrbuch, lv (2009), pp.353–90; George Frideric Handel: collected documents, i, pp.392–3, 398, 476.

For Handel and the Covent Garden oratorio seasons, see esp. D. Burrows, ‘Handel’s oratorio performances’, in The Cambridge companion to Handel, ed. Burrows, pp.262–81; E. Zöllner, English oratorio after Handel: the London oratorio series and its repertory, 1760–1800 (Marburg, 2002); P. Holman, Before the baton: musical direction and conducting in Stuart and Georgian Britain (Woodbridge, 2020), pp.130–4, 141–5. For Smith, see esp. B. M. Small, ‘John Christopher Smith junior (1712–1795): his life, selected works and his association with Handel’ (D.Phil. diss., University of Oxford, 2017).

George Frideric Handel: collected documents, iv, pp.864–5; see also Handel’s will: facsimiles and commentary, ed. D. Burrows (London, 2008). For an overview of the subsequent history of this bequest, see Small, ‘John Christopher Smith junior’, pp.158–69.

Smith senior seems to have called himself just Christopher Smith, not John Christopher Smith; see E. T. Harris, ‘Handel and his will’, in Handel’s will, ed. Burrows, pp.9–20, at p.12; D. Burrows, ‘Do we need “John?”’, Handel Institute Newsletter, xxx/1 (2019), p.3.

J. S. Hall, ‘John Christopher Smith, Handel’s friend and secretary’, The Musical Times, xcvi (1955), pp.132–4, at pp.133–4.

Transcribed in W. C. Smith, ‘More Handeliana’, Music & Letters, xxxiv/1 (1953), pp.11–24, at pp.14–15.

Public Advertiser, 18 February 1769; see also B. Kenyon de Pascual, ‘Handel’s harpsichords’, Early Music, xxi/2 (1993), p.335.

Holman, Before the baton, pp.258.

Daily Advertiser, 8 April 1775.

Zöllner, English oratorio after Handel, p.223.

Zöllner, English oratorio after Handel, pp.76–7.

A Catalogue of all the Capital Musical Instruments, Extensive and Valuable Collection of Manuscript and other Music by the most Eminent Composers, late the Property of John Stanley Esq. M.B. dec<eased>, Christie’s (24 June 1786), lot 76.

Morning Post, 22, 24 June 1786.

Daily Advertiser, 17 February 1775.

Makers of the harpsichord and clavichord, p.582; P. and A. Mactaggart, ‘A royal Ruckers: decorative and documentary history’, The Organ Yearbook, xiv (1983), pp.78–96; M. S. Waitzman, The Benton Fletcher Collection at Fenton House: early keyboard instruments (London, 2003), pp.36–9; Royal Collection Trust, rcin 690028, https://www.rct.uk/collection/69028 (accessed 22 January 2021).

O’Brien, Ruckers, esp. pp.178–81, 223–5, 243.

See, for instance, Waitzman, The Benton Fletcher Collection, p.36.

Hawkins, A general history, ii, p.912.

For Coxe, see J. Knight, ‘William Coxe’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography; The Clergy of the Church of England Database, https://theclergydatabase.org.uk/ (accessed 22 January 2021).

Anecdotes of George Frederick Handel and John Christopher Smith (London, 1799), p.55. The traditional attribution to Coxe is questioned in Smith, ‘More Handeliana’, pp.11–12.

Zöllner, English Oratorio after Handel, pp.128, 222.

D. Burrows, ‘The Royal Music Library and its Handel collection’, The Electronic British Library Journal (2009), article ii, pp.7–8, https://www.bl.uk/eblj/2009articles/articles.html (accessed 22 January 2021).

Charles Burney, An Account of the Musical Performances in Westminster Abbey and the Pantheon … in Commemoration of Handel (London, 1785; r/2003), i, pp.42–3.

Burrows, ‘The Royal Music Library’, pp.14, 16, 18–19.

Anecdotes of George Frederick Handel and John Christopher Smith, p.55. The bust is still in the Royal Collection at Windsor, rcin 35255; see https://www.rct.uk/collection/35255/george-frederick-handel-1685–1759 (accessed 22 January 2021).

George III & Queen Charlotte: patronage, collecting and court taste, ed. J. Roberts (London, 2004), pp.104–5.

Globe, 8 January 1811; Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser, 23 March 1812; ‘The King’, Examiner, no.361 (27 November 1814), p.763; Historical Manuscripts Commission, Report on the manuscripts of J. B. Fortescue Esq., preserved at Dropmore, 10 vols. (London, 1927), x, p.96.

Ipswich Journal, 12 January 1811.

Examiner, no.162 (3 February 1811), p.77. This report repeats mistaken claims made in the Morning Chronicle, 31 January 1811, that the harpsichord was at the Queen’s House, Frogmore, not at Windsor Castle.

Mactaggart, ‘A Royal Ruckers’, p.92; Waitzman, The Benton Fletcher Collection, p.39. 1612a hr has been identified (for instance, in Mactaggart, ‘A Royal Ruckers’, p.90, and the Royal Collection Trust website) as the ‘capital harpsichord by Rucker of Antwerp in a japanned case’ that was purchased by the Prince Regent in 1819 in the sale of the effects of Queen Charlotte and was subsequently moved to Carlton House. However, I believe that this was a different instrument, and will argue the case in ‘“Long Valued for the Fullness and Sweetness of their Tone”: 250 Years of Ruckers Harpsichords in Britain’.

For Hipkins, see esp. [F. G. Edwards], ‘Alfred James Hipkins’, The Musical Times, xxxix (1898), pp.581–6; H. Lieberson, Music and the new global culture: from the Great Exhibitions to the jazz age (Chicago, 2019), pp.47–78; Holman, ‘The harpsichord in nineteenth-century Britain’, pp.9–10.

Hipkins, ‘Handel’s harpsichords’, Athenaeum, p.379.

Hipkins, ‘Handel’s harpsichords’, The Musical Times, p.33; see also D. Hackett, ‘Harpsichords and spinets shown at the International Inventions Exhibition 1885, Royal Albert Hall’ (2017), no.35, http://www.friendsofsquarepianos.co.uk/app/download/30040181/Harpsichords+and+Spinets+shown+at+the+International+Inventions+Exhibition+1885+July+8th+%28Public%29.pdf (accessed 22 January 2021).

Mactaggart, ‘A Royal Ruckers’, p.93; Waitzman, The Benton Fletcher Collection, pp.12, 36.

Makers of the harpsichord and clavichord, p.582.

Victoria and Albert Museum, no.1079–1868, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O58984/harpsichord-ruckers-andreas-the/ (accessed 22 January 2021); see Catalogue of musical instruments in the Victoria and Albert Museum, Part 1: Keyboard instruments, comp. Schott, pp.53–6; Makers of the harpsichord and clavichord, pp.565–6.

Reported in Catalogue of musical instruments in the Victoria and Albert Museum, Part 1: Keyboard instruments, comp. Schott, p.56.

For Salaman’s recitals on old keyboard instruments, see Holman, ‘The harpsichord in nineteenth-century Britain’, pp.6–7, and the sources cited there.

‘Messrs. Broadwood’s Piano Manufactory’, The Illustrated London News, xxiii, no.948 (4 December 1858), p.528.

Published in Carl Engel, A descriptive catalogue of the musical instruments in the South Kensington Museum (London, 2/1874), pp.279, 281–2.

The letter was published in Victor Schœlcher, The life of Handel (London, 1857), pp.353–5; Engel, A Descriptive Catalogue, p.282; a slightly modernized version is in Russell, The harpsichord and clavichord, p.167. For Chard, see W. B. Squire, rev. A. Pimlott Baker, ‘George William Chard’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

For George Coxe, see his obituary, Gentleman’s Magazine, NS, xii (September 1844), pp.326–7; The Clergy of the Church of England Database. For the Coxe family, see Small, ‘John Christopher Smith junior’, p.273.

For Lady Rivers, see her obituary, Gentleman’s Magazine, NS, iii (April 1835), p.444.

For Wickham, see his memorial in Winchester Cathedral; a photograph can be seen at https://www.alamy.com/winchester-hampshire-winchester-cathedral-memorial-to-william-wickham-image7389010.html (accessed 22 January 2021).

For Hawtrey, see his obituary, Gentleman’s Magazine, lxxxviii/1 (1817), p.381; The Clergy of the Church of England Database.

Hipkins, ‘Handel’s harpsichords’, Athenaeum, p.379.

For Twining, see S. Lane-Poole, rev. A. Chahoud, ‘Thomas Twining’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography; on his musical activities, see P. Holman, ‘The Colchester partbooks’, Early Music, xxviii/4 (2000), pp.577–95.

R. S. Walker (ed.), A selection of Thomas Twining’s letters 1734–1804: the record of a tranquil life, 2 vols. (Lewiston, NY, 1991), i, pp.89–90, and (for Twining’s Pohlmann piano) p.92; A. Ribeiro (ed.), The letters of Dr Charles Burney, i: 1751–1784 (Oxford, 1991), pp.163–4.

Walker (ed.), A Selection of Thomas Twining’s letters, i, p.91.

National Archives, prob 11/1414, fols.368–70v.

Hipkins, ‘Handel’s harpsichords’, The Musical Times, p.31.

See T. A. B. Corley, ‘Richard Twining’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

See T. Deane, ‘Elizabeth Twining’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

C. Engel, Catalogue of the special collection of ancient musical instruments (London, 1872), p.11, no.9.

See ‘Andrew Brown Donaldson’, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrew_Brown_Donaldson (accessed 22 January 2021).

O’Brien, Ruckers, p.266; Makers of the harpsichord and clavichord, p.561; see also Yale Collection of Musical Instruments, no.4878.60 https://music.yale.edu/browse-collection/harpsichord-48781960 (accessed 22 January 2021). The stand does not belong to this instrument, but was transferred to it in the 1960s from 1638 ar, now in Copenhagen; see O’Brien, Ruckers, pp.266, 269.

Augustus W. Clarke, The Collection of Sir Algernon Oliphant Bart. of Worcester, England (New York, 26–9 April 1922), lot 453. I am grateful to Susan Thompson, Curator of the Yale Collection of Musical Instruments, for providing me with an extract from this sale catalogue.

For this disposition, see J. Koster, ‘History and construction of the harpsichord’, in The Cambridge companion to the harpsichord, ed. Kroll, pp.2–30, at pp.8, 11, 14, 15.

Daily Journal, 22 January 1729 (for an auction on 31 January).

Public Advertiser, 7 March 1772 (for an auction on 11 and 12 March).

Public Advertiser, 18 February 1769.

Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser, 12 February 1791; also World, 13 January 1791. The ‘pedal for double bass occasionally’ was probably a set of pulldown pedals connected to the bass of the harpsichord.

Three recordings can be played from the page at https://music.yale.edu/browse-collection/harpsichord-48781960 (accessed 22 January 2021).

For the long movement, see Holman, Before the baton, esp. pp.117–34, 143–9, 154–77, 337–44.

Benedict A. van Assen, ‘Interior of the Old Covent Garden Theatre’, Victoria and Albert Museum, s. 19–1997 <http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1138446/interior-of-the-old-covent-drawing-van-assen-benedict/>. For more on this picture, see Holman, Before the baton, pp.146–7.