-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Lea Tschaidse, Sophie Wimmer, Hanna F Nowotny, Matthias K Auer, Christian Lottspeich, Ilja Dubinski, Katharina A Schiergens, Heinrich Schmidt, Marcus Quinkler, Nicole Reisch, Frequency of stress dosing and adrenal crisis in paediatric and adult patients with congenital adrenal hyperplasia: a prospective study, European Journal of Endocrinology, Volume 190, Issue 4, April 2024, Pages 275–283, https://doi.org/10.1093/ejendo/lvae023

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Patients with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) require life-long glucocorticoid replacement, including stress dosing (SD). This study prospectively assessed adrenal crisis (AC) incidence, frequency, and details of SD and disease knowledge in adult and paediatric patients and their parents.

Prospective, observational study.

Data on AC and SD were collected via a patient diary. In case of AC, medical records were reviewed and patient interviews conducted. Adherence to sick day rules of the German Society of Endocrinology (DGE) and disease knowledge using the German version of the CAH knowledge assessment questionnaire (CAHKAQ) were assessed.

In 187 adult patients, the AC incidence was 8.4 per 100 patient years (py) and 5.1 in 100 py in 38 children. In adults, 195.4 SD episodes per 100 py were recorded, in children 169.7 per 100 py. In children 72.3% and in adults 34.8%, SD was performed according to the recommendations. Children scored higher on the CAHKAQ than adults (18.0 [1.0] vs 16.0 [4.0]; P = .001). In adults, there was a positive correlation of the frequency of SD and the incidence of AC (r = .235, P = .011) and CAHKAQ score (r = .233, P = .014), and between the incidence of AC and CAHKAQ (r = .193, P = .026).

The AC incidence and frequency of SD in children and adults with CAH are high. In contrast to the paediatric cohort, the majority of SD in adults was not in accordance with the DGE recommendations, underlining the need for structured and repeated education of patients with particular focus on transition.

This is the first prospective study to investigate the incidence of adrenal crisis and stress dosing episodes in adult and paediatric patients with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. We found a high incidence of adrenal crisis and stress dosing episodes in both our adult and paediatric patients. With about 72% of cases, the majority of stress dosing episodes in the children cohort were conducted in line with the recommendations of the German Society of Endocrinology (DGE), whilst only about 34% of the stress dosing episodes in the adult cohort were conducted correctly. This emphasizes the need for structured and repeated patient education to avoid inadequate stress dosing whilst preventing adrenal crises, with particular focus on the timing of transition.

Introduction

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency (21OHD) is an autosomal recessive disorder which is characterized by variable glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid deficiency and ACTH driven androgen excess. Patients with the most severe form, known as salt-wasting (SW) CAH, present with cortisol and aldosterone deficiency, whilst the simple-virilizing (SV) form only presents with cortisol deficiency. The mildest, non-classic (NC) form only occasionally presents with partial cortisol deficiency.1-3 With an incidence of 0.5 to 1 in 10 000,4 classic CAH is the most common genetic cause for primary adrenal insufficiency (PAI) in adult patients and the most common cause for PAI in children.2,5

Patients with adrenal insufficiency (AI) require life-long glucocorticoid (GC) substitution therapy to avoid life-threatening adrenal crisis (AC).1 Adrenal crisis is characterized by significant decline in overall health, presenting with various symptoms and characteristics (ie, reduced vigilance, nausea, vomiting, fever, electrolyte imbalance, hypoglycaemia, hypotension) and typically showing good response to parenteral hydrocortisone administration.1,6 Commonly reported triggers for AC are all forms of infectious diseases with and without fever, gastroenteritis being the most common in childhood and adults, and urinary and pulmonary infections in infants.6-8 Whilst healthy individuals typically experience a significant rise in the endogenous cortisol production during such periods of stress, this response is lacking or inadequate in patients with AI. Therefore, in stressful situations with increased cortisol demand, these patients require an increase in their regular GC dose, so-called stress dosing (SD), in order to prevent AC.7 For this purpose, patients with AI should be educated to identify potentially critical situations and be equipped with an emergency kit to be able to correctly perform SD and administer emergency medication.9 As the warning signs of imminent AC are often ambiguous, emergency GC treatment may be initiated too late. Thus, the effective prevention of AC remains a huge challenge in the management of patients with chronic AI and CAH in particular. A Swedish study identified AC as the main cause of death in 588 patients with CAH, exceeding cardiovascular deaths.10

Retrospective analysis in patients with chronic AI found an AC incidence between 4.4 and 6.3 crises per 100 patient years (py),11-13 similar results were found in retrospective studies focusing on patients with CAH.7,14,15 The only prospective analysis of AC incidence in patients with chronic AI shows an AC incidence of 8.3 per 100 py, suggesting an underestimation of real AC incidence in retrospective analyses.16

The most important aspect of AC prevention seems to be patient education on disease and SD17 as incorrect SD seems to be frequent.18 However, the effectiveness of this approach is debateable since educated patients with AI continue to experience a high AC incidence.16

Therefore, we conducted the first prospective study on SD and AC incidence in a large cohort of paediatric and adult patients with CAH. Additionally, the patient's knowledge about CAH was assessed as a possible influencing factor on SD and occurrence of AC.

Methods

Patients

Adult and paediatric patients with a diagnosis of CAH registered at the outpatient clinic of the University Hospital of Munich (Division of Paediatric Endocrinology at Dr. von Hauner Children's Hospital, Adult Endocrinology Clinic) and at the medical practice Endocrinology Charlottenburg, Berlin, Germany, were recruited to participate in this prospective study. Prior to study inclusion, written informed consent was obtained from all study participants and, in case of minors, of their parents. All patients with a confirmed diagnosis of classic CAH or non-classic CAH with a documented partial adrenal insufficiency could be included in this study. Baseline data were collected from each patient, such as age, sex, CAH type, and details of CAH-specific medication. The data collection was conducted between August 2016 and December 2021. All patients received standard regular short training and a short repetition and reminder of the basic sick day rules at every visit (usually yearly). Medical staff also reminded them on the application of emergency medication, and checked the emergency card and their emergency medication supply at each visit.

Diary

Patients were asked to document each event of SD in a patient diary, including the cause, which GC preparation was used for SD, what dosage, for how long, and in what form of administration (Supplementary material S3). Patients should also indicate whether the event resulted in adrenal crisis. In young paediatric patients, parents kept the diary for their children. The diary was considered not to be filled out properly if the patients stated that they had not documented all SD episodes during the observation period. The start and end date of diary keeping was documented, and the observation time for each patient was calculated in py.

If an AC was reported, the patient was interviewed in person or by telephone about the event, and the patient’s medical records were requested when possible. In accordance with Allolio,6 Hahner et al.,16 AC was defined as a severe deterioration of the general condition with at least 2 of the following aspects: Nausea or vomiting, severe fatigue, somnolence, fever, hypotension, hyponatraemia, hyperkalaemia, hypoglycaemia, or need for parenteral GC administration and improvement of health condition as result.

Stress dosing episodes conducted by patients were compared with the recommendations on sick day rules from the German emergency card for patients on hormone replacement therapy for diseases of the pituitary or adrenal gland in the version of 2020 from the German Society of Endocrinology (DGE), as depicted in Table 1. Therefore, each episode of SD was assessed in terms of the patient's stated reason for SD and whether it was necessary (guideline-compliant) or unnecessary (not guideline-compliant) in this situation. Stress dosing episodes classified as necessary (guideline-compliant) were then assessed in the next step with regard to administered GC dose, as too low, correct, and too high. Also documented were SD episodes which were conducted by a physician.

| Adults . | . |

|---|---|

| Slight injury, straining evening events, activity exceeding the usual | Possibly add 5-10 mg HC |

| Infection with mild to moderate illness without fever or significant distress (severe physical stress), severe pain, significant stress (bereavement, exam, wedding), dental procedures, minor outpatient procedures | Double daily dose, possibly add 5-10 mg HC in the evening |

| Acute illness and/or fever with severe feeling of illness | Triple daily dose or alternatively 30-20-10 mg HC (at daily dose ≤ 20 mg). Urgently seek medical help! |

| Persistent vomiting/diarrhoea or high fever (>39 °C) with severe feeling of illness | 100 mg HC (or other GC) as a self-injection i.m., s.c., or i.v. Seek medical attention immediately! |

| Children | |

| Mild mental or physical stress eg, competition, tournament, long hiking tour, long exam such as Abi exam or final exam, light dental treatment (eg, filling), emotional stress (bereavement, wedding) | Additional intake of a single dose, such as the midday or evening dose corresponding to the event |

| Mild infection with temperature < 38.5 °C and mild feeling of illness | Double daily dose |

| Illness with fever > 38.5 °C | >38.5 °C triple daily dose, >39.5 °C quadruple daily dose, dose increase until recovery, then return to standard dose within 1-2 days |

| In case of severe feeling of illness (regardless of temperature), reduction of general condition or change of consciousness, shock, trauma | i.m. or s.c. application of HC: Infants: 25 mg, nursery and primary school age: 50 mg, adolescents: 100 mg (alternative: Suppositories, not for diarrhoea!) seek medical attention after injection. Possibly continuation of HC therapy 100 mg/m2/24 h i.v. and IV therapy with NaCl 0.9%, glucose) |

| If oral intake is not possible (eg, due to gastrointestinal infection with vomiting) | i.m. or s.c. application of HC: Infants: 25 mg, nursery and primary school age: 50 mg, adolescents: 100 mg (alternative: GC Suppository,100 mg, not for diarrhoea! Seek medical attention after injection! |

| Adults . | . |

|---|---|

| Slight injury, straining evening events, activity exceeding the usual | Possibly add 5-10 mg HC |

| Infection with mild to moderate illness without fever or significant distress (severe physical stress), severe pain, significant stress (bereavement, exam, wedding), dental procedures, minor outpatient procedures | Double daily dose, possibly add 5-10 mg HC in the evening |

| Acute illness and/or fever with severe feeling of illness | Triple daily dose or alternatively 30-20-10 mg HC (at daily dose ≤ 20 mg). Urgently seek medical help! |

| Persistent vomiting/diarrhoea or high fever (>39 °C) with severe feeling of illness | 100 mg HC (or other GC) as a self-injection i.m., s.c., or i.v. Seek medical attention immediately! |

| Children | |

| Mild mental or physical stress eg, competition, tournament, long hiking tour, long exam such as Abi exam or final exam, light dental treatment (eg, filling), emotional stress (bereavement, wedding) | Additional intake of a single dose, such as the midday or evening dose corresponding to the event |

| Mild infection with temperature < 38.5 °C and mild feeling of illness | Double daily dose |

| Illness with fever > 38.5 °C | >38.5 °C triple daily dose, >39.5 °C quadruple daily dose, dose increase until recovery, then return to standard dose within 1-2 days |

| In case of severe feeling of illness (regardless of temperature), reduction of general condition or change of consciousness, shock, trauma | i.m. or s.c. application of HC: Infants: 25 mg, nursery and primary school age: 50 mg, adolescents: 100 mg (alternative: Suppositories, not for diarrhoea!) seek medical attention after injection. Possibly continuation of HC therapy 100 mg/m2/24 h i.v. and IV therapy with NaCl 0.9%, glucose) |

| If oral intake is not possible (eg, due to gastrointestinal infection with vomiting) | i.m. or s.c. application of HC: Infants: 25 mg, nursery and primary school age: 50 mg, adolescents: 100 mg (alternative: GC Suppository,100 mg, not for diarrhoea! Seek medical attention after injection! |

Abbreviations: GC, glucocorticoid; HC, hydrocortisone; i.m., intramuscular; i.v., intravenous; NaCl, sodium chloride; s.c., subcutaneous.

| Adults . | . |

|---|---|

| Slight injury, straining evening events, activity exceeding the usual | Possibly add 5-10 mg HC |

| Infection with mild to moderate illness without fever or significant distress (severe physical stress), severe pain, significant stress (bereavement, exam, wedding), dental procedures, minor outpatient procedures | Double daily dose, possibly add 5-10 mg HC in the evening |

| Acute illness and/or fever with severe feeling of illness | Triple daily dose or alternatively 30-20-10 mg HC (at daily dose ≤ 20 mg). Urgently seek medical help! |

| Persistent vomiting/diarrhoea or high fever (>39 °C) with severe feeling of illness | 100 mg HC (or other GC) as a self-injection i.m., s.c., or i.v. Seek medical attention immediately! |

| Children | |

| Mild mental or physical stress eg, competition, tournament, long hiking tour, long exam such as Abi exam or final exam, light dental treatment (eg, filling), emotional stress (bereavement, wedding) | Additional intake of a single dose, such as the midday or evening dose corresponding to the event |

| Mild infection with temperature < 38.5 °C and mild feeling of illness | Double daily dose |

| Illness with fever > 38.5 °C | >38.5 °C triple daily dose, >39.5 °C quadruple daily dose, dose increase until recovery, then return to standard dose within 1-2 days |

| In case of severe feeling of illness (regardless of temperature), reduction of general condition or change of consciousness, shock, trauma | i.m. or s.c. application of HC: Infants: 25 mg, nursery and primary school age: 50 mg, adolescents: 100 mg (alternative: Suppositories, not for diarrhoea!) seek medical attention after injection. Possibly continuation of HC therapy 100 mg/m2/24 h i.v. and IV therapy with NaCl 0.9%, glucose) |

| If oral intake is not possible (eg, due to gastrointestinal infection with vomiting) | i.m. or s.c. application of HC: Infants: 25 mg, nursery and primary school age: 50 mg, adolescents: 100 mg (alternative: GC Suppository,100 mg, not for diarrhoea! Seek medical attention after injection! |

| Adults . | . |

|---|---|

| Slight injury, straining evening events, activity exceeding the usual | Possibly add 5-10 mg HC |

| Infection with mild to moderate illness without fever or significant distress (severe physical stress), severe pain, significant stress (bereavement, exam, wedding), dental procedures, minor outpatient procedures | Double daily dose, possibly add 5-10 mg HC in the evening |

| Acute illness and/or fever with severe feeling of illness | Triple daily dose or alternatively 30-20-10 mg HC (at daily dose ≤ 20 mg). Urgently seek medical help! |

| Persistent vomiting/diarrhoea or high fever (>39 °C) with severe feeling of illness | 100 mg HC (or other GC) as a self-injection i.m., s.c., or i.v. Seek medical attention immediately! |

| Children | |

| Mild mental or physical stress eg, competition, tournament, long hiking tour, long exam such as Abi exam or final exam, light dental treatment (eg, filling), emotional stress (bereavement, wedding) | Additional intake of a single dose, such as the midday or evening dose corresponding to the event |

| Mild infection with temperature < 38.5 °C and mild feeling of illness | Double daily dose |

| Illness with fever > 38.5 °C | >38.5 °C triple daily dose, >39.5 °C quadruple daily dose, dose increase until recovery, then return to standard dose within 1-2 days |

| In case of severe feeling of illness (regardless of temperature), reduction of general condition or change of consciousness, shock, trauma | i.m. or s.c. application of HC: Infants: 25 mg, nursery and primary school age: 50 mg, adolescents: 100 mg (alternative: Suppositories, not for diarrhoea!) seek medical attention after injection. Possibly continuation of HC therapy 100 mg/m2/24 h i.v. and IV therapy with NaCl 0.9%, glucose) |

| If oral intake is not possible (eg, due to gastrointestinal infection with vomiting) | i.m. or s.c. application of HC: Infants: 25 mg, nursery and primary school age: 50 mg, adolescents: 100 mg (alternative: GC Suppository,100 mg, not for diarrhoea! Seek medical attention after injection! |

Abbreviations: GC, glucocorticoid; HC, hydrocortisone; i.m., intramuscular; i.v., intravenous; NaCl, sodium chloride; s.c., subcutaneous.

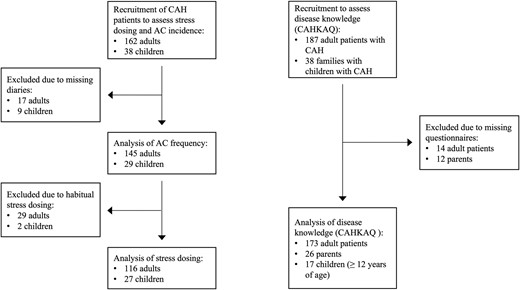

Concerning analysis of SD, habitual dose adjustment led to exclusion. This was defined as an average frequency of SD of 2 times or more per month or a duration of SD episodes of 14 days or more at a time during the observation period. An overview of the recruited study population and statistical analysis of subpopulations is given in Figure 1.

Flowchart of recruited patients and subpopulations of different analyses.

Questionnaire

To assess the patients' or parents' knowledge about CAH the CAH knowledge assessment questionnaire (CAHKAQ) in the German version was used, a validated instrument with 22 single-choice items (Supplementary material S4). Each question offers 4 possible answers, one of which is always “unsure”.19 Correct answers are summed up to a score, with higher scores indicating better disease knowledge.

Statistical analysis

All data were tested for normal distribution. Normally distributed data are given with mean and standard deviation, non-normally distributed data are given with median and interquartile range. Group comparisons for normally distributed data were made using t-test for independent samples, for non-normally distributed data using Mann-Whitney U or Kruskal-Wallis test. For correlation analysis, Spearman-Rho was used. For statistical analysis and graphical representation, SPSS version 26.0 and Prism 9 were used.

Results

Adrenal crisis

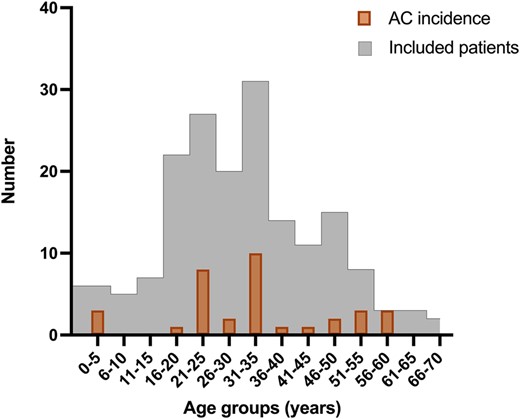

Overall, we found 34 AC in 429.2 py (7.9 AC in 100 py) across the entire study population. The frequency of AC in relation to age in both paediatric and adult patients, as well as included study patients, is shown in Figure 2. Basic characteristics of adult and paediatric patients with completed patient diaries and AC are given in Table 2.

Age-dependant distribution of AC. Number of AC, depicted in bold framed columns, in paediatric and adult patients distributed by age and in relation to number of included patients, histogramme framed with thin line; AC, adrenal crisis.

Basic characteristics of adult and paediatric patients with completed patient diaries and adrenal crisis.

| Characteristics . | Adult patients . | Paediatric patients . |

|---|---|---|

| Total number (n (%)) | 145 (100) | 29 (100) |

| Median age (range) in years | 32.0 (16.0-68.0) | 12.1 (0.7-18.9) |

| Sex (n (%)) | ||

| Female | 85 (58.6) | 15 (51.7) |

| Male | 60 (41.4) | 14 (48.3) |

| Phenotype (n (%)) | ||

| SW | 88 (60.7) | 23 (79.3) |

| SV | 49 (33.8) | 6 (20.7) |

| NC | 8 (5.5) | 0 (0) |

| First glucocorticoid preparation (n (%) Subgroups (n) | ||

| Hydrocortisone | 65 (44.8) 45 SW; 17 SV; 3 NC | 27 (93.1) 21 SW; 6 SV |

| Plenadren® | 7 (4.8) 4 SW; 2 SV; 1 NC | 1 (3.4) 1 SW |

| Efmody® | 13 (9.0) 5 SW; 8 SV | |

| Prednison | 9 (6.2) 5 SW; 4 SV | |

| Prednisolon | 42 (29.0) 21 SW; 17 SV; 4 NC | 1 (3.4) 1 SW |

| Dexamethason | 9 (6.2) 8 SW; 1 SV | |

| Second glucocorticoid preparation (n (%)) Subgroups (n) | ||

| None | 133 (91.7) 79 SW; 47 SV; 7 NC | 29 (100) |

| Hydrocortisone | 1 (0.7) 1 SW | |

| Prednisolone | 8 (5.5) 6 SW; 2 SV | |

| Dexamethasone | 3 (2.1) 2 SW; 1 NC | |

| HDE in mg/day (Md (IQR)) | 30.1 (13.8) | 22.5 (17.5) |

| SW | 30.0 (10.0) | 22.5 (15.0) |

| SV | 30.0 (15.0) | 26.3 (23.5) |

| NC | 15.0 (8.8) | |

| Mineralocorticoid medication | ||

| Yes | 90 (62.1) | 23 (79.3) |

| No | 55 (37.9) | 6 (20.7) |

| Mineralocorticoid in mg/day (Md (IQR)) | 0.05 (0.10) | 0.07 (0.06) |

| Total number of AC | 31 in 370.6 py | 3 in 58.6 py |

| 8.4 in 100 py | 5.1 in 100 py |

| Characteristics . | Adult patients . | Paediatric patients . |

|---|---|---|

| Total number (n (%)) | 145 (100) | 29 (100) |

| Median age (range) in years | 32.0 (16.0-68.0) | 12.1 (0.7-18.9) |

| Sex (n (%)) | ||

| Female | 85 (58.6) | 15 (51.7) |

| Male | 60 (41.4) | 14 (48.3) |

| Phenotype (n (%)) | ||

| SW | 88 (60.7) | 23 (79.3) |

| SV | 49 (33.8) | 6 (20.7) |

| NC | 8 (5.5) | 0 (0) |

| First glucocorticoid preparation (n (%) Subgroups (n) | ||

| Hydrocortisone | 65 (44.8) 45 SW; 17 SV; 3 NC | 27 (93.1) 21 SW; 6 SV |

| Plenadren® | 7 (4.8) 4 SW; 2 SV; 1 NC | 1 (3.4) 1 SW |

| Efmody® | 13 (9.0) 5 SW; 8 SV | |

| Prednison | 9 (6.2) 5 SW; 4 SV | |

| Prednisolon | 42 (29.0) 21 SW; 17 SV; 4 NC | 1 (3.4) 1 SW |

| Dexamethason | 9 (6.2) 8 SW; 1 SV | |

| Second glucocorticoid preparation (n (%)) Subgroups (n) | ||

| None | 133 (91.7) 79 SW; 47 SV; 7 NC | 29 (100) |

| Hydrocortisone | 1 (0.7) 1 SW | |

| Prednisolone | 8 (5.5) 6 SW; 2 SV | |

| Dexamethasone | 3 (2.1) 2 SW; 1 NC | |

| HDE in mg/day (Md (IQR)) | 30.1 (13.8) | 22.5 (17.5) |

| SW | 30.0 (10.0) | 22.5 (15.0) |

| SV | 30.0 (15.0) | 26.3 (23.5) |

| NC | 15.0 (8.8) | |

| Mineralocorticoid medication | ||

| Yes | 90 (62.1) | 23 (79.3) |

| No | 55 (37.9) | 6 (20.7) |

| Mineralocorticoid in mg/day (Md (IQR)) | 0.05 (0.10) | 0.07 (0.06) |

| Total number of AC | 31 in 370.6 py | 3 in 58.6 py |

| 8.4 in 100 py | 5.1 in 100 py |

Abbreviations: AC, adrenal crisis; HDE, hydrocortisone dose equivalent; NC, non-classic; py, patient years; SV, simple virilizing; SW, salt wasting.

Basic characteristics of adult and paediatric patients with completed patient diaries and adrenal crisis.

| Characteristics . | Adult patients . | Paediatric patients . |

|---|---|---|

| Total number (n (%)) | 145 (100) | 29 (100) |

| Median age (range) in years | 32.0 (16.0-68.0) | 12.1 (0.7-18.9) |

| Sex (n (%)) | ||

| Female | 85 (58.6) | 15 (51.7) |

| Male | 60 (41.4) | 14 (48.3) |

| Phenotype (n (%)) | ||

| SW | 88 (60.7) | 23 (79.3) |

| SV | 49 (33.8) | 6 (20.7) |

| NC | 8 (5.5) | 0 (0) |

| First glucocorticoid preparation (n (%) Subgroups (n) | ||

| Hydrocortisone | 65 (44.8) 45 SW; 17 SV; 3 NC | 27 (93.1) 21 SW; 6 SV |

| Plenadren® | 7 (4.8) 4 SW; 2 SV; 1 NC | 1 (3.4) 1 SW |

| Efmody® | 13 (9.0) 5 SW; 8 SV | |

| Prednison | 9 (6.2) 5 SW; 4 SV | |

| Prednisolon | 42 (29.0) 21 SW; 17 SV; 4 NC | 1 (3.4) 1 SW |

| Dexamethason | 9 (6.2) 8 SW; 1 SV | |

| Second glucocorticoid preparation (n (%)) Subgroups (n) | ||

| None | 133 (91.7) 79 SW; 47 SV; 7 NC | 29 (100) |

| Hydrocortisone | 1 (0.7) 1 SW | |

| Prednisolone | 8 (5.5) 6 SW; 2 SV | |

| Dexamethasone | 3 (2.1) 2 SW; 1 NC | |

| HDE in mg/day (Md (IQR)) | 30.1 (13.8) | 22.5 (17.5) |

| SW | 30.0 (10.0) | 22.5 (15.0) |

| SV | 30.0 (15.0) | 26.3 (23.5) |

| NC | 15.0 (8.8) | |

| Mineralocorticoid medication | ||

| Yes | 90 (62.1) | 23 (79.3) |

| No | 55 (37.9) | 6 (20.7) |

| Mineralocorticoid in mg/day (Md (IQR)) | 0.05 (0.10) | 0.07 (0.06) |

| Total number of AC | 31 in 370.6 py | 3 in 58.6 py |

| 8.4 in 100 py | 5.1 in 100 py |

| Characteristics . | Adult patients . | Paediatric patients . |

|---|---|---|

| Total number (n (%)) | 145 (100) | 29 (100) |

| Median age (range) in years | 32.0 (16.0-68.0) | 12.1 (0.7-18.9) |

| Sex (n (%)) | ||

| Female | 85 (58.6) | 15 (51.7) |

| Male | 60 (41.4) | 14 (48.3) |

| Phenotype (n (%)) | ||

| SW | 88 (60.7) | 23 (79.3) |

| SV | 49 (33.8) | 6 (20.7) |

| NC | 8 (5.5) | 0 (0) |

| First glucocorticoid preparation (n (%) Subgroups (n) | ||

| Hydrocortisone | 65 (44.8) 45 SW; 17 SV; 3 NC | 27 (93.1) 21 SW; 6 SV |

| Plenadren® | 7 (4.8) 4 SW; 2 SV; 1 NC | 1 (3.4) 1 SW |

| Efmody® | 13 (9.0) 5 SW; 8 SV | |

| Prednison | 9 (6.2) 5 SW; 4 SV | |

| Prednisolon | 42 (29.0) 21 SW; 17 SV; 4 NC | 1 (3.4) 1 SW |

| Dexamethason | 9 (6.2) 8 SW; 1 SV | |

| Second glucocorticoid preparation (n (%)) Subgroups (n) | ||

| None | 133 (91.7) 79 SW; 47 SV; 7 NC | 29 (100) |

| Hydrocortisone | 1 (0.7) 1 SW | |

| Prednisolone | 8 (5.5) 6 SW; 2 SV | |

| Dexamethasone | 3 (2.1) 2 SW; 1 NC | |

| HDE in mg/day (Md (IQR)) | 30.1 (13.8) | 22.5 (17.5) |

| SW | 30.0 (10.0) | 22.5 (15.0) |

| SV | 30.0 (15.0) | 26.3 (23.5) |

| NC | 15.0 (8.8) | |

| Mineralocorticoid medication | ||

| Yes | 90 (62.1) | 23 (79.3) |

| No | 55 (37.9) | 6 (20.7) |

| Mineralocorticoid in mg/day (Md (IQR)) | 0.05 (0.10) | 0.07 (0.06) |

| Total number of AC | 31 in 370.6 py | 3 in 58.6 py |

| 8.4 in 100 py | 5.1 in 100 py |

Abbreviations: AC, adrenal crisis; HDE, hydrocortisone dose equivalent; NC, non-classic; py, patient years; SV, simple virilizing; SW, salt wasting.

Adult patients

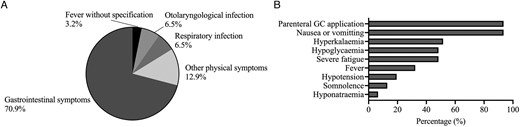

Of 162 recruited adult patients with CAH, 145 (89.5%) returned their completed diaries, with a median (min-max) observation time of 2.4 (0.2-5.0) years. Of these 145 adult patients, 21 patients reported 31 AC in a total of 370.6 py (8.4 AC per 100 py). The median age of patients with AC was 34.4 (18-57) years (11 [35.5%] male, 20 [64.5%] female; 19 [61.3%] SW, 12 [38.7%] SV). Of the 21 patients, who experienced an AC, 14 had SW CAH and received mineralocorticoid (MC) replacement therapy with a median dose of 0.875 (0.025-0.075) mg. There was no statistically significant difference in the median (IQR) AC frequency with regard to sex (male: 0.00 [0.00] vs female: 0.00 [0.00]; P = .982), CAH type (SW: 0.00 [0.00] vs SV: 0.00 [0.00]; P = .855), or GC replacement therapy (long-acting vs short-acting vs modified-release vs combination; P > .05). In a linear regression model, neither GC nor MC replacement therapy was a significant predictor for AC frequency. In the sub-cohort of patients with non-classic CAH and partial adrenal insufficiency, no AC was reported over the course of the study. An overview of causes of AC is depicted in Figure 3A. Characteristics and symptoms of AC were reported as follows: Nausea or vomiting in 29 (93.5%; 17 SW; 12 SV) cases, hyperkalaemia in 16 (51.6%; 13 SW, 3 SV) cases, hypoglycaemia in 15 (48.4%; 7 SW, 8 SV), severe fatigue in 15 (48.4%; 9 SW, 6 SV) cases, fever in 10 (32.3%; 5 SW, 5 SV) cases, hypotension in 6 (19.4%; 3 SW, 3 SV) cases, somnolence in 4 (12.9%; 4 SW, 0 SV) cases, and hyponatraemia in 2 (6.5%; 2 SW, 0 SV) cases, and in 29 cases (93.5%; 18 SW, 11 SV), parenteral GC application was necessary (Figure 3B).

Causes for and characteristics of AC in adult patients. Trigger (A) and characteristics (B) of adrenal crises in adult patients; GC, glucocorticoid.

In 21 cases (67.7%), AC led to hospital admission. In 6.5% of AC cases, only oral and in 25.8% of cases only parenteral GC application was performed. In 67.7% of cases, a combination of both oral and parental GC application was performed (rectal and subcutaneous in 3.2%, intramuscular in 16.1%, intravenous in 80.6%). In a total of 93.5% of cases, parenteral GC application was necessary. Multiple forms of parenteral GC application were documented in 1 AC. Oral, rectal, intramuscular, and subcutaneous administration was conducted by the patients, whilst intravenous administration was performed subsequently by medical personnel in a medical practice or hospital.

In 27 cases of AC, conventional HC was used as main GC preparation for SD, whilst prednisone/prednisolone was used in 4 cases. In 23 (74.2%) of AC cases, only 1 GC preparation was administered and in 8 (25.8%) of AC cases, an additional, different GC preparation was administered (1 HC; 1 modified-release HC, [MR-HC, Efmody®]; 5 prednisone/prednisolone; 1 dexamethasone).

In all 31 cases of AC, SD was performed and necessary. Only in 3 cases of AC (9.7%) dosage was too low according to the guidelines, whilst in 28 cases (90.3%) dosage was correct.

Paediatric patients

Of 38 recruited families with a child with CAH, 29 (76.3%) returned a completed diary, with a median (min-max) observation time of 2.1 (1.1-2.6) years. A total of 3 AC in 2 children were documented in a total of 58.6 py (5.1 AC in 100 py). The median age was 2.5 years at AC occurrence with a range from 1.2 to 3.8 years. One boy with SV CAH had 1 AC due to unknown trigger and 1 girl with SW CAH had 2 AC due to respiratory tract infection.

In all 3 cases, the children presented with severe fatigue, somnolence, and hyponatraemia, in 2 out of 3 cases, the children presented with nausea, vomiting, and hypotension, and in 1 out of 3 cases with fever, hypoglycaemia, and hyperkalaemia.

In all 3 AC, HC was administered for SD, and in 1 AC, prednisone was administered as a second GC preparation. Prior to hospital admission, rectal GC application was performed in 1 case and oral GC application was performed in another case. In all 3 AC, intravenous GC application was performed.

In all 3 cases of AC, SD was performed, necessary and conducted with correct dosage.

Stress dosing

In total, we found 678 SD episodes in 354.3 py (191.4 SD per 100 py) across the entire study population.

Adult patients

Of 145 adult patients with CAH, who had completed and returned their diaries, 29 patients were subsequently excluded from the main analysis due to habitual SD. This included 22 SW and 7 SV patients (13 male; 16 female) who reported a total of 776 SD episodes over a period of 71.1 years with a maximum duration of 1 SD episode of 72 days.

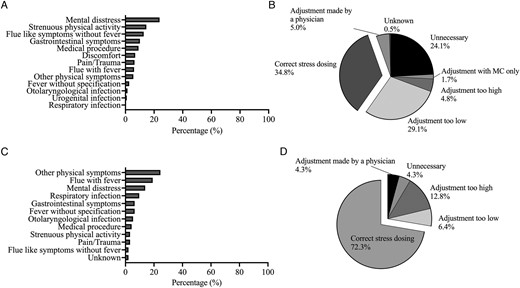

Of 116 patients, 26 (22.4%) reported no SD during the observation period, whilst 90 (77.6%) reported at least 1 SD episode during the observation period. In total, 584 SD episodes in 298.9 py were reported (195.4 SD episodes per 100 py). There was no statistically significant difference in the median frequency in SD with regard to sex (male: 2.0 [5.0] vs female: 3.0 [6.0], P = .829), CAH type (SW: 2.0 [5.0] vs SV: 3.5 [8.3], P = .111), or GC replacement therapy when corrected for multiple testing (long-acting vs short-acting vs modified-release vs combination; P > .05). Frequency of causes for SD is depicted in Figure 4A. In 93.0% of cases, SD was performed using only 1 GC preparation, and in 4.3%, 2 GC preparations were used (2.7% unknown). The form of drug administration during SD was reported in the following percentage: In 94.0% of cases oral, in 6.5% of cases intravenous, 0.9% intramuscular, and in 0.3% of cases rectal. The percentage of conventional HC used for SD was 61.3%, of MR-HC preparations 1.5%, of prednisone/prednisolone 29.7%, of dexamethasone 4.8%, and 2.7% unknown. A total of 10 episodes of SD involved a change of MC only (1.7%).

Causes for and evaluation of stress dosing. Frequency of causes for stress dosing in adult (A) and paediatric (C) patients and evaluation of stress dosing in adult (B) and paediatric patients (D) with regard to recommendations of the German Society of Endocrinology. MC, mineralocorticoid.

When compared to the sick day rules of the DGE, in 24.1% of cases in adult patients, SD was unnecessary and in 33.9% of cases, dosage of adjustment was incorrect. A total of 34.8% of SD in adults were performed correctly (Figure 4B). Concerning the most frequently stated cause for SD, mental distress, in 60.4% of cases SD was unnecessary and in a further 16.5% of cases, the dosage of adjustment was too low, whilst 23.0% of cases were conducted according to the guidelines.

Paediatric patients

Of 29 families with a child with CAH who had completed their diaries, 2 children were subsequently excluded from further analysis due to habitual SD (data not shown). This included 1 SW and SV paediatric patients (1 male; 1 female) who reported 160 SD episodes over a period of 3.2 years.

Of 27 children, 6 (22.2%) reported no SD during the observation period, whilst 21 (77.8%) reported at least 1 SD episode during the observation period. In total, 94 SD episodes in 55.4 py were reported (169.7 SD per 100 py). There was no significant difference in median frequency of SD with regard to sex (male: 2.5 [3.0] vs female: 2.0 [5.0], P = .981) or CAH type (SW: 2.0 [6.0] vs SV: 3.0 [3.0], P = .606). Causes and its frequencies for SD in children are depicted in Figure 4C.

Compared to the sick day rules of the DGE, 4.3% of SD was unnecessary and in 19.1% of cases, dosage of adjustment was incorrect. In a total of 72.3% of cases, SD was conducted correctly (Figure 4D).

CAHKA questionnaire

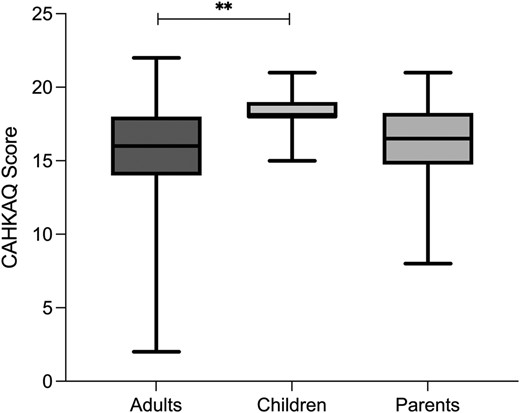

The total sample of n = 216 (Figure 1) achieved a median score (IQR) of 16.0 (4.0) out of a maximum score of 22. Topics in which less than 2/3 of the total cohort knew the correct answer included pathophysiology and inheritance of CAH, comorbidities, management of medication, as well as stress dosing and adrenal crises. When divided by group, the children cohort showed a significantly higher median score (IQR), compared to adult patients (18.0 [1.0] vs 16.0 [4.0]; P = .001), whilst there was no statistically significant difference between the parent cohort and the adult cohort (16.5 [4.0] vs 16.0 [4.0]; P = 1.0), as well as the children cohort (16.5 [4.0] vs 18.0 [1.0]; P = .07) when correcting for multiple testing (Figure 5).

CAHKAQ score. Depicted are the CAHKAQ scores achieved by the different groups and group comparison. Data are depicted as median (IQR). **P ≤ .01; CAHKAQ, congenital adrenal hyperplasia knowledge assessment questionnaire.

Correlations

Correlations between patient age, frequency of SD episodes, AC incidence, and the CAHKAQ scores of adult and paediatric patients as well as parents were performed. In the adult cohort, we found significant positive correlations between the frequency of SD an AC (r = .235; P = .011), between the CAHKAQ score and the frequency of SD (r = .233; P = .014), as well as between the CAHKAQ score and frequency of AC (r2 = .193; P = .026). Otherwise, we found no significant correlations in the adult, as well as in the children cohort (Supplementary material S1 and S2).

Discussion

This is the first study to prospectively assess the incidence and details of SD and AC in a large cohort of paediatric and adult patients with CAH. We observed a high incidence of AC in our adult cohort and a moderate AC incidence in our children cohort. Concerning SD episodes, we reported a surprisingly high incidence of SD episodes in both our adult and children cohorts. However, there was a clear difference as the majority of SD episodes in the adult cohort were not conducted in accordance to the recommendations of the DGE, whilst in the children, most SD episodes were performed guideline-compliant.

With 8.4 AC in 100 py, we found a higher incidence of AC in adult patients with CAH than reported in retrospective analysis on AC incidence in patients with CAH so far.7 However, this rate is comparable to the prospectively recorded AC incidence in adult patients with AI.16 Possible factors, such as underreporting in retrospective studies or a reporting bias, where patients who have not experienced an adrenal crisis may be less inclined to participate in such a study16 could contribute to this discrepancy. Furthermore, the possibility of overreporting in our study due to self-reporting should be considered when interpreting the high AC incidence in our cohort.

Concerning findings from earlier studies, suggesting that patients with PAI have an increased risk for AC compared to secondary adrenal insufficiency (SAI), do not align with our results.13 Additionally, our data do not support the hypothesis that patients with CAH have an even higher risk of developing AC due to a possible predisposition to infections.20 In line with previous studies, there was no significant difference in AC incidence between female and male patients.7,16 However, contrary to previous studies, we did not find a higher AC incidence in patients with SW CAH compared to SV CAH.7 We identified 2 peaks in AC incidence in early adulthood between 20-25 and 30-35 years of age, comparable to findings by the retrospective analysis by Reisch et al.7 However, this could also be influenced by a selection bias due to the rather young median age of our study sample.

Comparable to studies in AI,11,13,16,21 gastrointestinal complaints were by far the most frequent cause (71%) for an AC in the adult cohort. However, as gastrointestinal complaints are also common symptoms of AC (90% in our cohort), a clear distinction between trigger and symptom of AC is difficult.

In over 90% of AC cases, parenteral GC application, mostly intravenously by medical staff, was necessary. In almost 20% of AC, GC were administered subcutaneously or intramuscularly and therefore most likely by the patients or the social environment. This is a promising result, as the inhibition threshold for application by syringe can be high. Another favourable finding is that immediate-release hydrocortisone, the steroid medication with the quickest onset of effect, was by far the most utilized for SD in AC, which is generally recommended.9

In the children cohort, we found an AC incidence of 5.1 AC in 100 py. As mentioned above, data on AC incidence in children with treated AI and CAH in particular are scarce and show wide variability with AC incidences in retrospective analysis ranging from 2.7 to 6.5 AC in 100 py.14,22 As studies indicate the most AC in children to be up until the age of 5 to 6 years,7,15 with a median age of 12.2 years of our children cohort and only 6 children under the age of 5, the majority of children had already made it out of the vulnerable age. In line with this, the 3 AC that were reported in the children cohort were indeed in 2 children under the age of 5. In 72% of cases in the children’s cohort, SD was conducted according to recommendations, which may additionally contribute to low AC incidence. Nevertheless, data from the international I-CAH registry indicate an even lower AC incidence among 518 children with CAH than what was observed in our study, with between 2.7 and 3.9 AC per 100 py. This finding was interpreted as an improvement in educating patients and their parents, as well as medical staff and enhancing awareness for AC.14 It could, however, also reflect underreporting in the retrospective setup of the registry.

We also found a high frequency of SD in both cohorts, although about one-fifth of patients did not conduct SD during the observation period at all.

In adulthood, the leading cause for SD was mental distress in nearly one-quarter of cases, followed by strenuous physical activity. Less frequently documented were causes that are often reported as possible AC triggers in the literature, such as infections, fever, or gastrointestinal complaints.6 Thus, our cohort showed a large discrepancy in this regard, as no AC was triggered by mental distress. However, as some studies indicate that AC can be triggered by mental stress,11,16 the DGE recommends to adjust the dosage in cases of major mental or emotional stress (eg, death of a relative). Moreover, frequent SD during mental distress could have a preventive effect regarding the occurrence of AC in these patients.

About a quarter of the SD episodes in our adult cohort were conducted in situations that did not require SD at all. In nearly one-third of cases, SD was indeed indicated according to the guidelines, but the GC dosage of SD was incorrect. In very few cases, only a dose adjustment of the MC medication was made, which is not recommended at all.4 In total, only about one-third of the SD episodes in our adult cohort were according to the guidelines. This is a worrying result since patient education is one of the main elements in preventing AC in patients with AI and especially since all of the patients enclosed are treated at specialized centres where they receive education regarding their disease, emergency situations, and the necessity of SD. However, this seems to be insufficient in our cohort. Similar results were shown concerning SD in patients with AI, as a lack of SD was reported in situations where SD was strongly recommended, such as gastrointestinal complaints. At the same time, inappropriate SD with only a low symptom score was documented.18 It is also interesting to note the high number of SD and high incidence of AC at the same time, as one could assume AC prevention through frequent SD. But this seems not to be the case. A possible explanation for this could be, that patients who have experienced crises in the past, which is a known risk factor for future crises16 might be more sensible to the topic. Out of concern, they may tend to adjust their GC dose more often, leading to a positive association between frequency of SD and AC without necessarily reducing AC rate. Also, in our cohort, SD was made particularly in situations where no SD was indicated and when adjusted, the dosage was often too low. This is in line with a prospective study on patients with AI in which a high incidence of AC and a high AC associated mortality was found, although the patients had received detailed written instructions on SD.16 An important aspect that studies so far highlight is that a single patient education session may not be enough to achieve sufficient self-management skills. It was shown that only 1 or 2 educational consultations are not enough to attain lasting competence in self-management during stressful events in AI23 and that the patients' self-assessment of their knowledge on AI, SD, and self-management has already worsened within less than a year after having received standardized patient education compared to the initial testing and that less patients were willing to perform a self-injection and felt less confident in handling an AC.24 Therefore, repeated patient education and supervised practice of self-injection are essential. As in some cases, parenteral GC application is the only way to avert AC, lowering the barrier for self-application for patients is mandatory. A simple step is to educate about off-label subcutaneous application of GC instead of intramuscular, since studies showed a comparable efficacy.25 However, it must be emphasized at this point that the above described study involved healthy individuals and it is currently unclear how conditions, such as hypotension and vasoconstriction, can affect the absorption of subcutaneously administered GC. A promising idea for the future to facilitate self-application is a preloaded hydrocortisone syringe similar to an epinephrine pen, of which there are currently several products under development.22,26

The evaluation of the CAHKAQ revealed several areas of deficits. However, it is unclear whether the level of knowledge assessed has an influence on AC incidence, as there was a positive correlation between the CAHKAQ score and the frequency of SD in the adult cohort.

In contrast to the adult cohort, in the children's cohort, 73% of SD was correct. This could be due to the involvement of parents as SD in childhood is also substantially conducted by the parents as well as to shortcomings in transition. A study conducted on transition readiness in adolescents and young adults with rare endocrine disorders revealed that 20% of patients receiving GC therapy were unaware of the need for SD in specific situations and the potential consequences of not making such SD.27

Limitations of our study are a rather small children cohort from only 1 centre, therefore a recruitment bias cannot be ruled out and effects on statistical analysis and results are possible. Also, frequency of discomfort and sick days without SD was not reported. On the other hand, our study features some key strengths, such as its prospective design, a large cohort of adult patients with CAH, and detailed documentation on SD and AC.

Our data emphasize the need for repeated and structured patient education with regard to SD and management of AC but also concerning CAH in general. Additionally, these data highlight the gap between paediatric and adult care and the importance of a successful transition programme.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ann-Christin Welp and Magdalena Maurer for their valuable support and all participants for taking part in this study.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Journal of Endocrinology online.

Funding

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Heisenberg Professorship 325768017 to N.R. and Projektnummer: 314061271-TRR205 to N.R.). The funding sources had no role in the design of the study, collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, writing of the report, and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Authors’ contributions

Lea Tschaidse (Conceptualization [equal], Data curation [lead], Formal analysis [lead], Investigation [equal], Methodology [equal], Project administration [lead], Validation [equal], Visualization [lead], Writing—original draft [lead]), Sophie Wimmer (Data curation [equal], Formal analysis [equal], Investigation [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Hanna Nowotny (Data curation [equal], Investigation [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Matthias Auer (Data curation [equal], Formal analysis [equal], Investigation [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Christian Lottspeich (Data curation [equal], Investigation [equal], Methodology [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Ilja Dubinski (Data curation [equal], Investigation [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Katharina Schiergens (Data curation [equal], Investigation [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Heinrich Schmidt (Data curation [equal], Investigation [equal], Supervision [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Marcus Quinkler (Data curation [equal], Investigation [equal], Methodology [equal], Supervision [equal], Validation [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), and Nicole Reisch (Conceptualization [lead], Funding acquisition [lead], Investigation [lead], Methodology [lead], Resources [equal], Supervision [lead], Validation [lead], Writing—review & editing [equal])

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by Ethikkommission der Medizinischen Fakultät der LMU München (ethical approval nos. 19-0558 and 19-557) and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written consent has been obtained from each patient after full explanation of the purpose and nature of all procedures used.

References

Author notes

Conflict of interest: All authors declare no conflict of interest. Co-author N.R. is on the editorial board of EJE. She was not involved in the review or editorial process for this paper, on which she is listed as author.