-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Antonio D'Andrilli, Giulio Maurizi, Claudio Andreetti, Anna Maria Ciccone, Mohsen Ibrahim, Camilla Poggi, Federico Venuta, Erino Angelo Rendina, Long-term results of laryngotracheal resection for benign stenosis from a series of 109 consecutive patients , European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery, Volume 50, Issue 1, July 2016, Pages 105–109, https://doi.org/10.1093/ejcts/ezv471

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Long-term results of patients undergoing laryngotracheal resection for benign stenosis are reported. This is the largest series ever published.

Between 1991 and March 2015, 109 consecutive patients (64 males, 45 females; mean age 39 ± 10.9 years) underwent laryngotracheal resection for subglottic postintubation (93) or idiopathic (16) stenosis. Preoperative procedures included tracheostomy in 35 patients, laser in 17 and laser plus stenting in 18. The upper limit of the stenosis ranged between actual involvement of the vocal cords and 1.5 cm from the glottis. Airway resection length ranged between 1.5 and 6 cm (mean 3.4 ± 0.8 cm) and it was over 4.5 cm in 14 patients. Laryngotracheal release was performed in 9 patients (suprahyoid in 7, pericardial in 1 and suprahyoid + pericardial in 1).

There was no perioperative mortality. Ninety-nine patients (90.8%) had excellent or good early results. Ten patients (9.2%) experienced complications including restenosis in 8, dehiscence in 1 and glottic oedema requiring tracheostomy in 1. Restenosis was treated in all 8 patients with endoscopic procedures (5 laser, 2 laser + stent, 1 mechanical dilatation). The patient with anastomotic dehiscence required temporary tracheostomy closed after 1 year with no sequelae. One patient presenting postoperative glottic oedema underwent permanent tracheostomy. Minor complications occurred in 4 patients (3 wound infections, 1 atrial fibrillation). Definitive excellent or good results were achieved in 94.5% of patients. Twenty-eight post-coma patients with neuropsychiatric disorders showed no increased complication and failure rate.

Laryngotracheal resection is the definitive curative treatment for subglottic stenosis allowing very high success rate at long term. Early complications can be managed by endoscopic procedures achieving excellent and stable results over time.

INTRODUCTION

Treatment of stenosis involving the subglottic region is a major therapeutic challenge. This poses increased technical problems with respect to the treatment of simple tracheal stenosis, mainly because the space below the vocal cords is the narrowest segment of the airway, and due to the need for extending the resection to the cricoid near the vocal cords.

Main causes of subglottic stenosis are benign and most frequently include acquired inflammatory postintubation or post-tracheostomy disease. Idiopathic stricture, which is a more rare condition, represents the second most frequent cause.

Technical principles for a safe laryngotracheal resection preserving the posterior cricoid plate and the laryngeal nerves were first described in 1974 by Gerwat and Brice [ 1 ] and in 1975 by Pearson et al . [ 2 ], who popularized the most frequently used technique worldwide. Particular care must be taken when considering partial removal of the cricoid cartilage since the laryngeal nerves have access into the airway wall at the level of its posterior plate whose upper border supports the arytaenoids cartilages which play a major role in vocal cord function.

Main alternative therapy is represented by endoscopic procedures, but benefits are generally temporary and repeated treatments are often required [ 3 , 4 ]. Other laryngoplasty techniques even without complete resection of the diseased segment have been proposed principally by otolaryngologists and especially when the vocal cords are involved, but they have shown lower success rates at long term with prolonged need for postoperative stenting [ 5–7 ].

However, so far only few centres have achieved adequate experience in laryngotracheal surgery, and published series with long-term results after resection for subglottic stenosis are limited although the safety and efficacy of this type of surgery has been clearly proved [ 8–10 ].

We report results at long term of laryngotracheal resection analysing a series of 109 consecutive patients with benign subglottic stenosis, which represents the largest series reported so far.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Between 1991 and March 2015, 109 consecutive patients (64 males, 45 females) with benign subglottic stenosis underwent laryngotracheal resection and reconstruction at our institution. The standard Pearson technique was used in all patients but one with glottis involvement who received a partial laryngofissure. The mean age of patients was 39 ± 10.9 (range 14–71). Ninety-five of these patients had been operated since 2003.

The cause of stenosis was postintubation injury in 93 patients and idiopathic in 16. Distance of the upper limit of the stenosis from the vocal cords ranged between actual involvement of vocal cords and 1.5 cm from the glottis. Stenosis grade was from 60 to 100% of the airway lumen. Tracheomalacia was associated in 20 patients. At the time of surgery, 35 patients presented with tracheostomy, which had been performed in other centres in 33 of them. The operation was performed after single or multiple laser procedures in 35 patients, associated with Dumon silicone stent in 18 of them. The stents were all positioned with the proximal limit close to the vocal cords. Placement of endotracheal prosthesis was preferred in these patients to allow stabilization of the stenosis without tracheostomy or to achieve improvement of general conditions before surgery in compromised patients. Stents were removed at the time of operation in 12 patients and before surgery (range 7–30 days) in 6 patients. The quality of mucosa in patients with the stent removed at the time of surgery was generally worse because of inflammation.

Since our hospital is a tertiary referral centre, patients included in this series came from different centres and underwent preoperative procedures (dilatation, laser, stenting or tracheostomy) based on variable indications and protocols.

Systemic and local antibiotics were administered in patients with tracheostomy showing evidence of infection in this site until complete sterilization was achieved.

Laryngotracheal resection was generally performed after having assessed the stenosis stabilization endoscopically. However, we have observed that the fundamental technical aspect was to perform resection on healthy mucosa independently of the status of the stenotic segment.

Preoperative assessment by laryngotracheal endoscopic examination aimed to evaluate the mobility and trophicity of the vocal cords, severity and extent of the stricture, grade of inflammation and presence of oedema or malacia. Since 2003 preoperative study has been completed with neck and chest computed tomography scan with spiral technique allowing a more precise evaluation of the tracheal wall status (calcification, malacia) and of the extraluminal structures and tissue.

Twenty-eight patients of this series presented with post-coma neurological and/or psychiatric disorders. Seventeen of these had severe neurological deficits (3 were tetraplegic), 10 showed post-coma psychiatric syndrome (associated with paraplegia in 1) and 1 was autistic. These patients provided very limited or no cooperation in the postoperative period.

As already reported [ 11 ], after surgery all patients were observed until death or last date of follow-up (31 May 2015). Anatomical and functional control was performed by flexible laryngotracheoscopy at discharge, 1 and 3 months after surgery, and then every 3 months for the first year, every 6 months in the second year and once a year for the following time. No patient was lost at follow-up.

The results were classified as excellent if respiration and voice appeared completely normal and bronchoscopy showed a normal diameter of the airway. Outcome was considered good in the presence of minor sequelae on voice and/or breathing not influencing the quality of life. The results were considered satisfactory when abnormal voice, narrowed anastomosis and shortness of breath on exercise were found, but not affecting normal activities. In case of major complications or permanent tracheostomy or stenting, results were judged not satisfactory. Morphological, anatomical and functional evaluation after surgery was performed by the same surgical team in accordance with what reported by patients.

Quantitative variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

Intraoperative management and surgical technique

In case of tight stenosis limiting the possibility of intubation and not receiving preoperative dilatation or laser ablation, usually a small calibre (4–4.5) endotracheal tube was passed through the stenosis, and this was generally sufficient for adequate ventilation until the trachea was exposed and incised allowing cross-field intubation. Occasionally, the tube was placed immediately above the stenosis. In patients with pre-existing tracheostomy, intubation was done through the stoma, which was later resected together with the stenotic segment.

All the operations have been performed based on the principles described by Pearson et al. [ 2 ]. We have reported our standard technique in previous publications [ 3 , 4 ]. Laryngotracheal anastomosis is generally performed with interrupted sutures of 3-0 absorbable monofilament material [Polydioxanone (PDS)] tied outside. More recently, in some patients a running suture (3-0 or 4-0 PDS) has been used for the posterior membranous wall of the anastomosis. This technical alternative is quicker and has been used at surgeon's discretion to reduce operative time in patients with limited anastomotic tension after short segment resection.

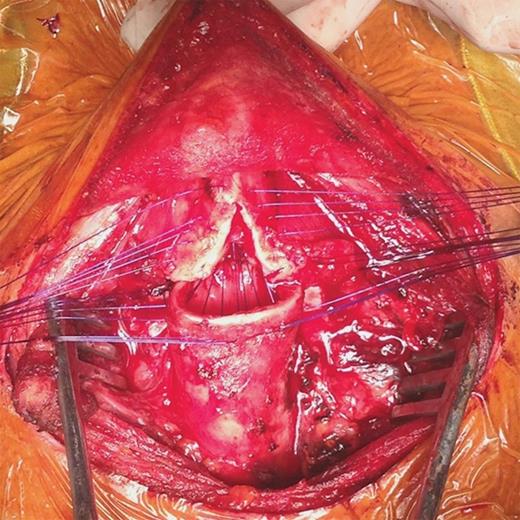

In patients with actual involvement of the vocal cords, a variation of the standard technique was employed; after resection of the cricoid ring and cricothyroid membrane, the thyroid cartilage was incised longitudinally on the midline for an extent of 1–1.5 cm (partial laryngofissure). The margins were then retracted laterally to increase the airway space and the lower trachea was directly anastomosed to the retracted ends of the incised thyroid cartilage (Fig. 1 ). This partial laryngofissure proved sufficient to obtain an optimal calibre of the subglottic space.

Intraoperative view of thyrotracheal anastomosis after cricotracheal resection with partial laryngofissure for idiopathic stenosis involving the vocal cords. Interrupted sutures have been placed but are still untied.

A nasotracheal tube is left in place uncuffed in the awakened patient for 24 h and then removed after bronchoscopic check of the anastomosis and vocal cords. The tube is kept with the tip distal to the anastomosis to protect it and to allow safe tracheobronchial toilette. Also the patient undergoing partial laryngofissure did not need postoperative stenting.

Two strong chin–chest sutures are placed at the end of operation in all patients to maintain cervical flexion and are generally removed after 4–8 days depending on the length of the resected segment and on the anastomosis tension degree.

RESULTS

There was no intraoperative or postoperative mortality. Postoperative hospitalization ranged between 3 and 19 days (mean 9 ± 1.8 days). The mean length of the airway resection was 3.4 ± 0.8 cm (range 1.5–6 cm). Resection of a tracheal segment longer than 4.5 cm was performed in 14 patients.

Laryngotracheal release was performed in 9 patients receiving long segment laryngotracheal resection to reduce tension on the anastomosis. This was suprahyoid release in 7 patients, pericardial in 1 and suprahyoid associated with pericardial in 1. Pericardial release was performed through a right lateral minithoracotomy (6 cm). In all other patients, standard mobilization of the trachea was sufficient for a tension-free anastomosis.

Definitive extubation was possible in the first postoperative day in 99 patients. Four patients, after extubation at 24 h, had to be reintubated within a few hours because of glottic oedema. Definitive re-extubation was possible, after steroid therapy, 2 days later in 1 patient and 3 days later in other 2 patients. One patient could not be re-extubated because of persistent glottis oedema and received permanent tracheostomy. In 6 patients, the nasotracheal tube was left in site for a longer time (2 days in 4 patients, 3 days in 2 patients) because of severe glottis oedema visible at operation without need for further reintubation.

Ninety-nine patients (90.8%) had excellent or good early results. Immediate postoperative outcome was considered excellent in 85 of these (78%) and good in 14 (12.8%). Ten patients (9.2%) experienced complications including restenosis in 8, dehiscence in 1 and glottic oedema requiring tracheostomy in 1. Recurrence of stenosis was diagnosed within 1 month of the operation in 5 patients, and between 2 and 3 months from the operation in 3. Restenosis was treated in all 8 patients with endoscopic procedures. These included laser treatment in 5 patients, laser ablation with stenting (Dumon stent) in 2 and mechanical dilatation in 1. Endotracheal stent was removed after 6 months in 1 patient and after 1 year in the other. Patient with anastomotic dehiscence required temporary tracheostomy closed after 1 year with no sequelae. Minor complications occurred in 4 patients (3 wound infections, 1 atrial fibrillation).

As already described [ 11 ], 1 patient showing good results at 1 month presented 2 months later with shortness of breath and reduced mobility of the vocal cords limiting respiratory space, but anatomical and functional conditions returned good after 3 months of steroid and aerosol therapy.

Definitive results appeared excellent in 87 patients (79.8%), good in 16 (14.7%) and satisfactory in 5 (4.6%). Twenty-eight post-coma patients with neurological and/or psychiatric disorders showed no significantly increased complication and failure rate. Early complications and failure rate was 7%. Definitive failure rate was 3.5%.

Early failure rate in the subgroup of patients (16) with idiopathic stenosis was 6.3%. Definitive success rate in this group after endoscopic treatment of restenosis was 100%.

The mean follow-up time was 52.9 ± 31.4 (range 3–248 months). Four patients died of other causes. All the other living patients present normal voice and respiration except for the 5 patients in whom definitive results were considered satisfactory (abnormal voice or narrowed anastomosis not affecting normal activities) and for the patient with permanent tracheostomy. All patients with postoperative complications but one (who received permanent tracheostomy) show stable results at long term.

DISCUSSION

To date single-staged laryngotracheal resection with primary end-to-end anastomosis has proved to offer the best option of cure for benign subglottic stenosis allowing definitive and stable high success rate. Major published series in this setting report good to excellent outcome in more than 90% of patients at long term with perioperative mortality under 1–2% [ 9–17 ]. Major surgical morbidity is generally limited, with restenosis rate of 0–11% [ 9–16 ], anastomotic dehiscence rate of 0–5% [ 9–16 ] and reoperation rate of 0–3% [ 9–16 ] (Table 1 ).

Main published series of patients undergoing laryngotracheal resection for benign stenosis

| Author (year) . | Patients ( n ) . | Diagnosis . | Results . | Complications . | Restenosis . | Dehiscence . | Mortality . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Success . | Failure . | |||||||

| Grillo et al. (1995) [ 10 ] | 62 | PI | 92% | 8% | 12.9% | 8.1% a | 8.1% a | 2.4% |

| Couraud et al. (1995) [ 9 ] | 57 | PI, PT, ID | 98.2% | 1.8% | 3.5% | 0 | 1.8% | 1.8% |

| Macchiarini et al. (2001) [ 12 ] | 45 | PI | 96% | 4% | 41% b | 4.4% | 0 | 2% |

| Ashiku et al. (2004) [ 13 ] | 73 | ID | 91% | 9% | 17.8% | 9.5% | 0 | 0 |

| Marulli et al. (2008) [ 14 ] | 37 | PI, PT, ID | Early 89% Definitive 97% | Early 11% Definitive 3% | 8.1% | 5.5% | 5.5% | 0 |

| Morcillo et al. (2013) [ 16 ] | 60 | ID | Early 91.7% Definitive 98% | Early 8.3% Definitive 2% | 28% b | 3.3% | 3.3% | 0 |

| Present series | 109 | PI, ID | Early 91% Definitive 99.1% | Early 9% Definitive 0.9% | 9.2% | 7.4% | 0.9% | 0 |

| Author (year) . | Patients ( n ) . | Diagnosis . | Results . | Complications . | Restenosis . | Dehiscence . | Mortality . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Success . | Failure . | |||||||

| Grillo et al. (1995) [ 10 ] | 62 | PI | 92% | 8% | 12.9% | 8.1% a | 8.1% a | 2.4% |

| Couraud et al. (1995) [ 9 ] | 57 | PI, PT, ID | 98.2% | 1.8% | 3.5% | 0 | 1.8% | 1.8% |

| Macchiarini et al. (2001) [ 12 ] | 45 | PI | 96% | 4% | 41% b | 4.4% | 0 | 2% |

| Ashiku et al. (2004) [ 13 ] | 73 | ID | 91% | 9% | 17.8% | 9.5% | 0 | 0 |

| Marulli et al. (2008) [ 14 ] | 37 | PI, PT, ID | Early 89% Definitive 97% | Early 11% Definitive 3% | 8.1% | 5.5% | 5.5% | 0 |

| Morcillo et al. (2013) [ 16 ] | 60 | ID | Early 91.7% Definitive 98% | Early 8.3% Definitive 2% | 28% b | 3.3% | 3.3% | 0 |

| Present series | 109 | PI, ID | Early 91% Definitive 99.1% | Early 9% Definitive 0.9% | 9.2% | 7.4% | 0.9% | 0 |

PI: postintubation; PT: post-traumatic; ID: idiopathic.

a Restenosis + dehiscence.

b Major + minor.

Main published series of patients undergoing laryngotracheal resection for benign stenosis

| Author (year) . | Patients ( n ) . | Diagnosis . | Results . | Complications . | Restenosis . | Dehiscence . | Mortality . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Success . | Failure . | |||||||

| Grillo et al. (1995) [ 10 ] | 62 | PI | 92% | 8% | 12.9% | 8.1% a | 8.1% a | 2.4% |

| Couraud et al. (1995) [ 9 ] | 57 | PI, PT, ID | 98.2% | 1.8% | 3.5% | 0 | 1.8% | 1.8% |

| Macchiarini et al. (2001) [ 12 ] | 45 | PI | 96% | 4% | 41% b | 4.4% | 0 | 2% |

| Ashiku et al. (2004) [ 13 ] | 73 | ID | 91% | 9% | 17.8% | 9.5% | 0 | 0 |

| Marulli et al. (2008) [ 14 ] | 37 | PI, PT, ID | Early 89% Definitive 97% | Early 11% Definitive 3% | 8.1% | 5.5% | 5.5% | 0 |

| Morcillo et al. (2013) [ 16 ] | 60 | ID | Early 91.7% Definitive 98% | Early 8.3% Definitive 2% | 28% b | 3.3% | 3.3% | 0 |

| Present series | 109 | PI, ID | Early 91% Definitive 99.1% | Early 9% Definitive 0.9% | 9.2% | 7.4% | 0.9% | 0 |

| Author (year) . | Patients ( n ) . | Diagnosis . | Results . | Complications . | Restenosis . | Dehiscence . | Mortality . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Success . | Failure . | |||||||

| Grillo et al. (1995) [ 10 ] | 62 | PI | 92% | 8% | 12.9% | 8.1% a | 8.1% a | 2.4% |

| Couraud et al. (1995) [ 9 ] | 57 | PI, PT, ID | 98.2% | 1.8% | 3.5% | 0 | 1.8% | 1.8% |

| Macchiarini et al. (2001) [ 12 ] | 45 | PI | 96% | 4% | 41% b | 4.4% | 0 | 2% |

| Ashiku et al. (2004) [ 13 ] | 73 | ID | 91% | 9% | 17.8% | 9.5% | 0 | 0 |

| Marulli et al. (2008) [ 14 ] | 37 | PI, PT, ID | Early 89% Definitive 97% | Early 11% Definitive 3% | 8.1% | 5.5% | 5.5% | 0 |

| Morcillo et al. (2013) [ 16 ] | 60 | ID | Early 91.7% Definitive 98% | Early 8.3% Definitive 2% | 28% b | 3.3% | 3.3% | 0 |

| Present series | 109 | PI, ID | Early 91% Definitive 99.1% | Early 9% Definitive 0.9% | 9.2% | 7.4% | 0.9% | 0 |

PI: postintubation; PT: post-traumatic; ID: idiopathic.

a Restenosis + dehiscence.

b Major + minor.

Some other reconstruction techniques have been used in recent decades to manage laryngotracheal stenosis with the aim of obtaining a permanent enlargement of the subglottic airway. These interventions, principally popularized by otorhinolaryngologists, include the vertical division of the anterior and posterior wall of the cricoid cartilage and the insertion of an autologous tissue graft (usually bone or cartilage) between the divided cartilaginous portions. Although the rate of satisfactory results with these techniques in some experiences has been reported as high as 76–80% [ 5 , 6 ], the need for prolonged postoperative stenting is almost a rule, resulting in impossible extubation in up to 25% of patients [ 5 ]. In our opinion therefore, indication for these procedures should be restricted to cases with clear involvement of the glottis in which standard cricotracheal resection and reconstruction could not be sufficient to ensure adequate airway lumen. Our technique of partial anterior laryngofissure overcomes this problem and assures wide airway calibre.

Most popular alternative therapy is represented by endoscopic procedures (laser, mechanical dilatation, stenting). However, these treatments, although safe, rarely provide durable efficacy when the stenosis is in the subglottic region. Restenosis is a frequent finding and repeated procedures are required, so producing additional tracheal damage and increased technical difficulty for definitive surgical treatment. Especially when a stent is placed, this can extend the area of airway injury and be responsible for further complications such as granuloma formation or prosthesis migration [ 4 ]. The latter techniques are therefore mainly employed to stabilize the stenosis before surgery and to achieve an acceptable palliation in patients who are temporarily or permanently not suitable for surgery.

Also the use of temporary Montgomery T-tube or tracheostomy has been significantly reduced over time because of the related disadvantages of potentially extending the tracheal stricture and of favouring bacterial colonization.

In our experience, all 8 patients showing restenosis after surgery had complete and stable resolution of this complication after treatment with simple endoscopic procedures (laser with or without stenting, mechanical dilatation) allowing good to excellent final results at long term with no recurrence of stenosis. This proves that even in patients experiencing early failure of the surgical procedure, final and durable success can be still obtained without reoperation. We think therefore that endoscopic procedures can play a crucial role after resection in the management of complicated patients, thus limiting the need for redo surgery.

We believe that even in patients with anastomosis close to the vocal cords or increased risk of postoperative glottis oedema, protection tracheostomy after resection is generally not needed. In such cases, we prefer to leave the tube in place for a longer time (48–72 h) after surgery while administering steroid therapy since we have proved that with this strategy definitive extubation within few days can be obtained in almost all patients without sequelae.

Sixteen patients in our series underwent laryngotracheal resection for idiopathic stenosis. This rare disease with unknown cause has been described by some authors [ 18 ] as potentially progressive, generally associated with severe inflammation which often involves the vocal cords or the space just below. Due to such characteristics, controversies have been expressed in the literature concerning the optimal management strategy and the appropriateness of surgical resection. Because of the high risk of leaving partially involved tissue with possible consequences for future recurrence, some authors believe that crycotracheal resection should not be indicated [ 18 ].

Dedo and Catten [ 18 ] after having analysed a series of 52 patients with idiopathic stenosis concluded that this is a progressive disease that cannot be cured and hence advocated repeated palliative procedures indefinitely. In this experience, all 7 patients treated with resection had restenosis. The 43 patients undergoing only endoscopic treatments received an average of 8 procedures each, but 17 patients required permanent tracheostomy and only 21 patients appeared disease free over the long term.

However, Grillo et al. [ 19 ] reported a 91% rate of good to excellent outcome over a series of 35 single-staged laryngotracheal resections for idiopathic stenosis. Similarly, Ashiku et al. [ 13 ] observed the same rate (91%) of patients with good to excellent long-term results without need for further intervention. More recently, Morcillo et al. [ 16 ] in a Spanish multi-institutional study which included 60 patients receiving resection using different techniques (with or without postoperative temporary stenting) reported a 97% final success rate with no mortality.

In our series, all 16 patients with idiopathic stenosis undergoing laryngotracheal resection showed satisfactory to excellent long-term results with no recurrence. Most of them presented with the upper limit of the stenosis and inflammation close to the glottis. Demanding excision of extramucosal scar tissue at the level of the cricoid cartilage was required in most cases, especially on the posterior plane with thyrotracheal anastomosis performed close to the vocal cords. On the basis of our outstanding results and on similar evidence coming from other large experiences in the literature, we and other authors believe that single-staged laryngotracheal resection and reconstruction can be considered an effective definitive cure for such patients allowing stable long-term results if the operation is performed with correct timing and adequate technical experience [ 13 , 16 , 19 ].

A peculiar aspect of the present series is the inclusion of a large group of patients (28) with neurological or psychiatric post-coma disorders who can only provide very limited collaboration in the early postoperative period. Results observed in all these patients were in line with those observed in the remaining population with no mortality, similar complication rate and final success rate. Neurological or psychiatric disorders, rendering full body control or tolerance of neck flexion impossible, have been considered as general contraindication to surgery in the past. We think that, based on the present results, surgical resection should no longer be denied in this setting.

Besides meticulous surgical technique, we believe that the key to success in such patients should include detailed preoperative information of patients and their relatives about the operation and the postoperative course; intensive postoperative nurse assistance by highly qualified personnel with experience with tracheal surgery patients; tight cooperation of the personnel with the patients' relatives in the postoperative setting; accelerated postoperative course.

Recommendations of the present authors for the treatment of laryngotracheal stenosis based on their long-term experience are the following: endoscopic procedures (mechanical dilatation, laser and stenting) can be considered as first-line option only in patients with simple stenosis including granuloma or web-like lesions. Surgery should be the therapeutic option of choice in all cases of complex laryngotracheal stenosis or recurrence after endoscopic treatment of simple stenosis.

In conclusion, laryngotracheal resection is the definitive curative treatment for subglottic stenosis allowing very high success rate at long-term even in patients with idiopathic stenosis and neuro-psychiatric disorders. Early complications can be managed by endoscopic procedures achieving excellent and stable results over time.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Marta Silvi for data management and editorial work.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

APPENDIX. CONFERENCE DISCUSSION

Dr P. Van Schil(Antwerp, Belgium) : The authors report a series of 109 consecutive patients who underwent laryngotracheal resection for a benign subglottic or idiopathic stenosis. Excellent or good results were obtained in 91% of the patient.

I have two questions. First, the criteria for evaluation of these patients are somewhat subjective. How were they determined and validated, and who exactly performed the postoperative evaluation? Secondly, what are the authors’ current indications for mechanical dilatation, laser treatment, or primary laryngeal resection?

Dr D'Andrilli: Concerning the first question, criteria for evaluation, as you know, there are still no standardised criteria to evaluate results after laryngotracheal resection. Similarly, there is no official validation of this criteria. We have used the criteria that have been currently used in some of the main European series that have been also reported by Dr Dartevelle and colleagues in 2000. We consider excellent results in the case of a completely normal voice and bronchoscopic control. We consider good results in the presence of minor sequelae on voice and the anastomosis, but not affecting the quality of life. Satisfactory results are considered those with an abnormality in voice and narrowing with anastomosis, shortness of breath on exercise, but not affecting the normal daily activities. Failure, is in the case of major complications or a need for permanent tracheostomy or permanent stenting. These are very similar criteria that have been used, even in the published series from the Massachusetts General Hospital. Morphological, anatomical and functional evaluation after surgery has been performed by the same surgical team in our institution at the same follow-up time. So it was a homogeneous evaluation performed based on clinical and bronchoscopic evidences.

Concerning the second question, the indication for endoscopic procedures, you have to consider that our hospital is a tertiary referral centre, so patients undergoing surgery came from different centres and were managed with different indications and different protocols. Our approach is that laryngotracheal resection is the best curative treatment. It should be considered the first-line treatment in every case of complex subglottic stenosis. Endoscopic treatments can be indicated in the case of simple stenosis, and we consider simple stenosis granuloma or web-like lesions, but in the case of recurrence, surgery should be considered and indicated.

Author notes

Presented at the 29th Annual Meeting of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 3–7 October 2015.