-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Sokratis Tsagkaropoulos, Ann Belmans, Geert M. Verleden, Willy Coosemans, Herbert Decaluwe, Paul De Leyn, Philippe Nafteux, Dirk Van Raemdonck, Single-lung transplantation: does side matter?, European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery, Volume 40, Issue 2, August 2011, Pages e83–e92, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcts.2011.03.011

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Objective: Single-lung transplantation (SLTx) is a valid treatment option for patients with non-suppurative end-stage pulmonary disease. This strategy helps to overcome current organ shortage. Side is usually chosen based on pre-transplant quantitative perfusion scan, unless specific recipient considerations or contralateral lung offer dictates opposite side. It remains largely unknown whether outcome differs between left (L) versus right (R) SLTx. Methods: Between July 1991 and July 2009, 142 first SLTx (M/F = 87/55; age = 59 (29–69) years) were performed from 142 deceased donors (M/F = 81/61; age = 40 (14–66) years) with a median follow-up of 32 (0–202) months. Indications for SLTx were emphysema (55.6%), pulmonary fibrosis (36.6%), primary pulmonary hypertension (0.7%), and others (7.0%). Recipients of L-SLTx (n = 72) and R-SLTx (n = 70) were compared for donor and recipient characteristics and for early and late outcome. Results: Donors of L-SLTx were younger (37 (14–65) vs 43 (16–66) years; p = 0.033). R-SLTx recipients had more often emphysema (67.1% vs 44.4%; p = 0.046) and replacement of native lung with ≥50% perfusion (47.1% vs 23.6%; p = 0.003). The need for bypass, time to extubation, intensive care unit (ICU) and hospital stay, and 30-day mortality did not differ between groups. Overall survival at 1, 3, and 5 years was 78.4%, 60.5%, and 49.4%, respectively, with a median survival of 60 months, with no significant differences between sides. Forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) improved (p ≪ 0.01) in both groups to comparable values up to 36 months. Complications overall (44.4% vs 50.0%) or in allograft (25.0% vs 24.3.0%) as well as time to bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS) (35 months) and 5-year freedom from BOS (68.9% vs 75.0%) were comparable after L-SLTx versus R-SLTx, respectively. There were no differences in all causes of death (p = 0.766). On multivariate analysis, BOS was a strong negative predictor for survival (hazard ratio (HR) 6.78; p ≪ 0.001), whereas side and mismatch for perfusion were not. Conclusion: The preferred side for SLTx differed between fibrotic versus emphysema recipients. Transplant side does not influence recipient survival, freedom from BOS, complications, or pulmonary function after SLTx. Besides surgical considerations in the recipient, offer of a donor lung opposite to the preferred side should not be a reason to postpone the transplantation until a better-matched donor is found.

1 Introduction

Lung transplantation (LTx) is an effective treatment modality for selected patients suffering from any form of end-stage pulmonary disease. Early and late survival rates have improved in recent years [1]. Besides the occasional heart–lung transplantation (HLTx) in patients with Eisenmenger’s syndrome or complex congenital heart disease, two transplant types mostly used are single-lung transplantation (SLTx) and bilateral-lung transplantation (BLTx).

Since the first reports of successful SLTx for pulmonary fibrosis by the Toronto Lung Transplant Group in 1986 [2] and for emphysema by the Paris Group in 1989 [3], indications and LTx type have evolved over the past two decades with, currently, a preference for BLTx because of superior long-term survival compared with SLTx, both in patients with emphysema [4] and pulmonary fibrosis [5]. As a result, the proportion of SLTx compared with BLTx reported to the Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) has decreased over recent years [1].

SLTx is contraindicated in patients with suppurative lung diseases, such as cystic fibrosis or bronchiectasis, for reasons of infectious risk and imminent death from pulmonary sepsis. The technique is also not recommended in patients with pulmonary vascular disease and associated pulmonary arterial hypertension because of the increased risk for massive reperfusion edema and dysfunction of the allograft early on. Moreover, severe ventilation–perfusion mismatch may occur once chronic rejection and bronchiolitis obliterans develop in the allograft later on [6]. Most SLTx nowadays are performed in elderly patients with smoking-induced emphysema or pulmonary fibrosis [1]. The latter indication is still believed to be the ideal disease for SLTx because both ventilation and perfusion will be largely directed toward the newly implanted allograft [2].

Recipient factors that may play a role in listing a patient for either SLTx or BLTx are: type of the underlying lung disease, age and general condition, history of previous chest surgical interventions, or specific unilateral problem, such as after previous pneumonectomy [7]. Further, donor factors can be decisive for transplant side in case the quality of the contralateral donor lung precludes its use [8]. Center experience and annual transplant volume may also play a role, as SLTx is a less complex and a more straightforward procedure compared with BLTx. Finally, SLTx is preferred by some teams as a strategy helping to overcome current organ shortage with reduced time and mortality on the waiting list [9].

There is little evidence to support decision making which side to transplant when SLTx is considered. In clinical practice, the side is usually chosen based on findings on pre-transplant quantitative lung perfusion scan. In normal subjects, each lung is approximately equally perfused (right (R) lung 55%, left (L) lung 45%). In patients with end-stage parenchymal or vascular lung disease, the distribution may be unequal [10], and the less-perfused lung is then preferentially explanted and replaced, whenever surgically possible.

It remains largely unknown whether outcome differs after L-SLTx versus R-SLTx. This review of our lung-transplant cohort aimed to compare the characteristics and the outcome in L versus R single-lung recipients.

2 Patients and methods

2.1 Study design

Informed consent for data analysis was obtained from all recipients, according to the Belgian law on patients’ rights regarding data registration. Approval for analyzing recorded data was waived by the institutional ethics committee on human research, given the retrospective nature of the study.

All consecutive LTx procedures (n = 493) performed at the University Hospitals Leuven between July 1991 and July 2009 were reviewed using a prospectively gathered database. There were 150 SLTx, 301 BLTx and 42 HLTx performed during the study period. The annual numbers and percentages of single versus bilateral transplant procedures are presented in Table 1 . A shift from SLTx to BLTx as procedure of choice was noted over the years. However, the proportion of L-SLTx versus R-SLTx did not change when compared per decade (1991–2000: 27 L vs 26 R; 2001–2009: 48 L vs 49 R). Of these 150 SLTx procedures, eight SLTx procedures were excluded from the study, as no native lung was left in place in the recipient. Four recipients were retransplanted for bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS), including two contralateral SLTx (n = 2) after first SLTx (n = 2) and two BLTx after first SLTx (n = 2). Two recipients with cystic fibrosis had previously undergone pneumonectomy for septic complications 1 day (n = 1) and 23 years (n = 1) prior to SLTx.

Annual number and percentage of single versus bilateral-lung transplants performed at the University Hospitals Leuven between July 1991 and July 2009.

2.2 Recipients and donors

Donor and recipient characteristics are listed in Table 2 . This study comprises 142 first SLTx recipients with a median age of 59 (29–69) years. Eighty-seven (61.3%) recipients were male. Two paired recipients received one allograft each from one donor (twinning procedure). These donors were counted twice in the analysis. Their median age was 40 (14–66) years. Eighty-one (57.0%) donors were male. Donor–recipient matching was based on blood group identity (compatibility) and predicted total lung capacity (TLC), but not on age, gender, or cytomegalovirus status.

Donor and recipient characteristics in left versus right single-lung recipients.

2.3 Indications

Patients considered for SLTx were evaluated according to the ISHLT guidelines [11]. The main indications for SLTx in our recipients were emphysema in 79 (55.6%) patients and pulmonary fibrosis in 52 (36.6%), followed by primary pulmonary hypertension in one patient (0.7%), and miscellaneous in 10 patients (7.0%).

2.4 Side

L-SLTx versus R-SLTx was well distributed (n = 72 vs n = 70, respectively). The side of transplantation was chosen preferentially, based on pre-transplant quantitative perfusion scan. A total of 92 recipients (64.8%) were transplanted on the side with the lowest perfusion, whereas the opposite side was dictated for various reasons in 50 patients (35.2%), including previous surgical procedures on the preferred side (biopsies, drains, and pleurodesis), opposite donor lung already accepted by other lung-transplant team, or preferred donor lung not transplantable because of poor quality.

2.5 Operative technique

All transplant procedures were performed by five fully trained general thoracic surgeons. SLTx was done through a posterolateral thoracotomy in all recipients. The operative technique did not differ according to the side. Our institutional policy is to avoid extracorporeal support for SLTx (and BLTx), except in case of hemodynamic instability or unacceptable gas exchange during surgery. All decisions to commence extracorporeal support were made ad hoc by the transplanting team.

2.6 Waiting time and follow-up

The median time of the recipients on the waiting list was 127 (1–1196) days and the median follow-up after SLTx was 32 (0–202) months, with no significant differences between both sides (Table 2).

2.7 Study parameters

L- and R-lung recipients were compared for donor and recipient demographics and other characteristics. Early (hospital) outcome was compared between both sides with respect to the need for peroperative bypass, time to extubation, stay in the intensive care unit (ICU), postoperative hospital stay, and 30-day mortality. Parameters of late outcome were defined as complications in native lung or in allograft, time to and freedom from BOS, overall survival, and all causes of death. Forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) was measured prior to discharge and further at 3, 6, 12, and 36 months after SLTx.

2.8 Statistical analysis

All baseline characteristics for donors and recipients are summarized by transplant side (L vs R). Continuous variables are presented as median (range) and compared using the Mann–Whitney U-test. Categorical data are presented as frequencies (percentages) and compared with the chi-square test.

Three outcomes were of specific interest: overall survival, freedom from BOS, and improvement in pulmonary function (FEV1) after SLTx. The probability of survival is estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and groups were compared using the log-rank test. For BOS, the cumulative incidence function (CIF) was estimated and compared between the two groups using the Pepe–Mori test. Furthermore, for overall mortality, Cox regression analyses were performed including the following independent variables: sex, sex mismatch, side, side mismatch for perfusion, BOS, cardiac arrhythmias, length of ICU stay, and length of hospital stay. BOS was included as a time-varying covariate. All variables were primarily assessed in univariate analyses and consequently all were included in a multivariable Cox regression. The model assumptions of linearity for the continuous variables and proportional hazards were assessed using the method described by Lin, Wei, and Ying using cumulative martingale residuals (Lin D, Wei L, Ying Z. Checking the Cox model with cumulative sums of martingale based residuals. Biometrika 1993;80:557–72). In addition, subgroup analyses were performed for all variables in the model, and their interaction with transplant side was assessed by a likelihood ratio test. The results of the subgroup analyses are presented in a forest plot. For the analysis of FEV1, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures was performed on the changes in the post-transplant measurements using PROC MIXED in SAS. An unstructured covariance matrix was used to account for possible interdependencies between the visits. To approach a scenario of missingness at random (MAR), the variables that were included in the Cox regression analyses were included in the ANOVA. The assumption of MAR can be considered appropriate, if all factors influencing missingness are included in the model. Under the assumption of MAR, the results of the ANOVA are unbiased.

Statistical significance was assessed at a significance level of 5%. Due to the exploratory nature of the study, no adjustments were made to the significance level to account for multiple testing. All analyses were performed using Statistica 7.0 (StatSoft Inc, Tulsa, OK, USA) and SAS version 9.22 for Windows.

3 Results

3.1 Donors and recipients

Donor and recipient characteristics classified according to side of SLTx are presented in Table 2. A significant difference in donor age (37 (14–65) years vs 43 (16–66) years; p = 0.033) and in cause of death (cerebrovascular accident in 38.9% vs 52.9%; p = 0.049) was noticed between L- and R-lung recipients, respectively. No other differences in donor gender, ventilation time, and oxygenation were seen between sides.

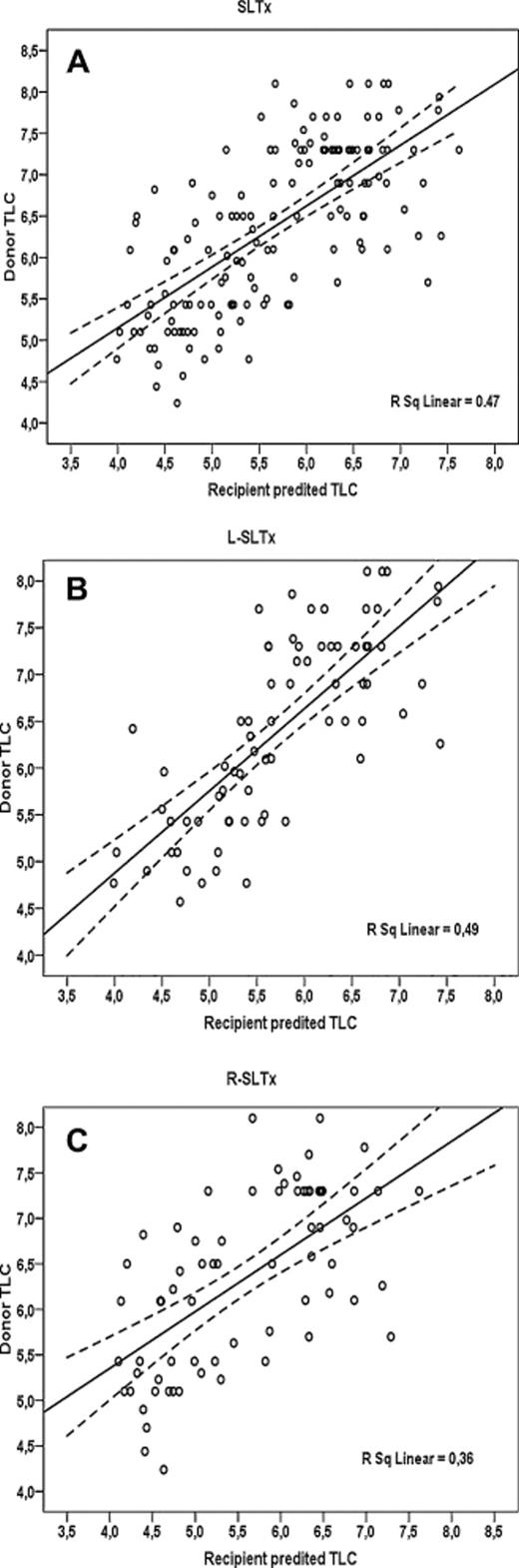

No significant differences in recipient age and gender were found between both groups (Table 2). Patients with emphysema had more frequently R-SLTx, whereas L-SLTx was performed more in pulmonary fibrosis patients (p = 0.046). No significant difference in donor-/recipient-predicted TLC was seen between L- versus R-lung recipients (1.12 (0.78–1.53) vs 1.14 (0.87–1.55), respectively; p = 0.301). The relation between donor- and recipient-predicted TLC in all SLTx, L-SLTx, and R-SLTx is plotted in Fig. 1 (r2 = 0.47, 0.49, and 0.36, respectively). Patients after R-SLTx (47.1%) had significantly more side mismatch for perfusion (>50% of cardiac output to explanted lung) compared with L-SLTx (23.6%); p = 0.003.

Donor versus recipient predicted total lung capacity (TLC) for all single-lung transplantation (SLTx), left (L) SLTx, and right (R) SLTx.

3.2 Hospital outcome

Early outcome in L- and R-lung recipients is compared in Table 3 .

Early and late outcome in left versus right single-lung recipients.

One patient with primary pulmonary hypertension needed partial cardiopulmonary bypass to implant the left allograft. The proportion of extracorporeal support needed in other recipients did not differ between L-SLTx (18.1%) and R-SLTx (14.3%).

No significant differences were found between groups in time to extubation, length of ICU and hospital stay, and 30-day mortality (Table 3).

Cardiac arrhythmias after SLTx were equally observed in both groups.

3.3 Late outcome

Late outcome between L- and R-lung recipients is compared in Table 3. No differences in bacterial, viral, or fungal infections in the allograft, malignancies, or other complications were seen between groups. Further, no differences in native lung complications (infection, tumor, pneumothorax, and hyperinflation) were observed. Two male patients after L-SLTx needed pneumonectomy of the contralateral, native lung for chronic infection (one emphysema patient after 18 months for invasive aspergillosis and one fibrosis patient after 38 months for lung abscess).

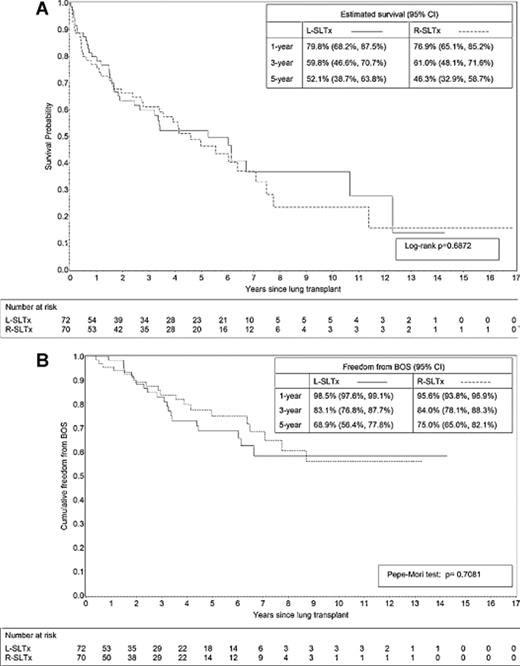

At the end of the study, 39 patients had died after R-SLTx versus 38 after L-SLTx. No significant differences in cause of death were noticed between both groups (Table 3). Overall survival after SLTx was 78.4% (70.5–84.3), 60.5% (51.5–68.4), and 49.4% (40.0–58.1) at 1, 3, and 5 years, respectively. No significant difference in survival was found between both sides (Fig. 2(A) ) with a median survival of 63 months in L-lung recipients and 55 months in R-lung recipients.

Kaplan–Meier curves for (A) overall survival and (B) freedom from bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS) after left (L) versus right (R single-lung transplantation (SLTx).

BOS was diagnosed in 20 patients after L-SLTx versus in 19 patients after R-SLTx (NS). The median time to develop BOS was 35 (5–104) months and did not differ between sides (Table 3). Freedom from BOS was 97.1% (96.1–97.8), 83.6% (79.5–86.9), and 72.2% (64.7–78.0) at 1, 3, and 5 years after SLTx, respectively and did not differ between L- versus R-lung recipients (Fig. 2(B)).

3.4 Cox regression and interaction analysis

On univariate analysis, female patients had a better overall survival compared with males (hazard ratio (HR) 0.52 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.31–0.86); p = 0.01). Gender mismatch between donor and recipient (HR 2.10 (95% CI 1.04–4.24); p = 0.04), length of ICU stay (HR 1.06 (95% CI 1.02–1.10); p ≪ 0.01), hospital stay (HR 1.03 (95% CI 1.01–1.05); p ≪ 0.01), and the presence of BOS (HR 6.44 (95% CI 3.50–11.85); p ≪ 0.0001) were significant negative predictive factors for survival after SLTx. Cardiac arrhythmias (p = 0.13) and side mismatch for perfusion (p = 0.08) were not significant predictors of survival. On multivariate analysis, female gender (HR 0.44 (95% CI 0.26–0.74); p = 0.002) and BOS (HR 6.78 (95% CI 3.63–12.65); p ≪ 0.0001) remained the only predictors of survival (Table 4 ).

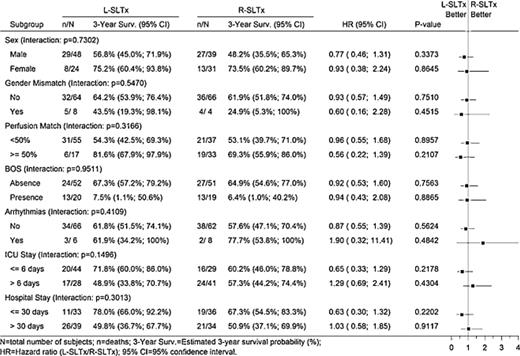

Subgroup analyses were performed for all variables in the model, and their interaction with transplant side was assessed. Inspection of the forest plot presented in Fig. 3 reveals that no differences between transplant sides were found in any of the subgroups and that none of the interactions were statistically significant.

Forest Plot for overall survival. SLTx: single-lung transplantation; L, left; R, right; BOS, bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome; ICU, intensive care unit.

3.5 Pulmonary function

Improvement in FEV1 from pre-transplant value to all post-transplant values was significant (p ≪ 0.01) up to 36 months, both after L-SLTx and R-SLTx (Fig. 4 ).

Forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) over time from pre-transplant value (pre) to first measurement post-transplant (M1), up to 3 years after single-lung transplantation (SLTx). *p ≪ 0.01 compared to pre-transplant value for L-SLTx; ^p ≪ 0.01 compared to pre-transplant value for R-SLTx.

An overall test for transplant side including all variables analyzed in the repeated-measures ANOVA yielded a p-value of 0.1827, indicating no difference in FEV1 over time between sides.

4 Discussion

In the present study, we failed to find a difference in early and late outcome between recipients of left versus right single-donor lungs. In particular, the need for perioperative bypass, the time to extubation, the length of ICU stay and hospital stay, and 30-day mortality were comparable between both groups. Further, overall survival and freedom from BOS were not different according to the side of SLTx. Post-transplant FEV1 was also not different between groups, indicating that both R- and L-lung transplantation can lead to a comparable improvement in pulmonary function for at least 3 years after SLTx. The proportional imbalance between both diagnostic groups with more emphysema patients having R-SLTx and more fibrosis patients undergoing L-SLTx is the reflection of the preferred side at the time our patients were listed for transplantation. In patients with an equal (up to 10% difference) distribution of blood flow between L and R lung, we prefer to transplant the L (larger) donor lung into a fibrotic patient with a small chest cavity, as the liver on the right side may prohibit a downward replacement of the diaphragm. Inversely, we prefer to transplant the R donor lung (smaller volume to oversized) into an emphysematous patient with a large chest cavity. This is to avoid compression by a remaining hyperinflated, emphysematous R native lung in case of L-SLTx, as previously believed [12].

Survival at 1, 3, and 5 years after SLTx in our cohort was 78.4%, 60.5%, and 49.4%, respectively. These results compare favorably with those reported by Cai in 2007, based on United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) registry data (76.0% and 41.8% for L-SLTx and 78.3% and 44.8% for R-SLTx at 1 and 5 years) [13]. In a recent review of 1000 adult lung transplants by the University of Washington lung-transplant group at St Louis, survival rates of 82.1%, 68.2%, 47.6%, and 20.1% were reported at 1, 3, 5, and 10 years after SLTx, respectively [14].

On univariate analysis, perfusion-side mismatch was not found to be a clear predictive factor for survival after SLTx (HR = 1.54; p = 0.08). Further analysis yielded no statistically significant interaction between perfusion-side mismatch and transplant side (HR 0.96 vs HR 0.56 for ≪50% vs ≥50% perfusion to explanted lung) (Fig. 3). Recently, Fox and colleagues reported that graft-side mismatching for perfusion after SLTx does not carry an apparent risk for the recipient, as it can result in similar outcome [15]. The remaining contralateral lung can often ensure adequate oxygenation and hemodynamic stability during the surgical procedure, especially in patients without secondary pulmonary hypertension (e.g., emphysema). This finding therefore suggests that transplanting the ‘wrong side’ is feasible and should not be considered a contraindication for transplantation [15].

Survival was also better in female recipients on univariate and multivariate analysis. A similar finding in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was reported previously [13]. A significant survival difference according to gender has also been observed in the ISHLT Registry in favor of female recipients [1]. In our study, donor-to-recipient gender mismatch was a negative predictive factor for survival on univariate analysis (HR 2.10; p = 0.04), but no longer on multivariate analysis. This finding parallels the observation in another study analyzing the data from the ISHLT Registry [16]. Female donor-to-male recipient transplant was associated with higher 30-day mortality, even after adjusting for size mismatch and diagnosis, whereas female donor-to-female recipient was beneficial. Further analysis showed that a male donor to a female recipient increases the relative risk for 5-year mortality by 16%. Roberts and colleagues also examined the impact of donor–recipient gender mismatching on survival and came to opposite conclusions. A significant improvement in overall survival as well as a longer period of freedom from BOS was found for gender-mismatched donor and recipient pairs [17]. The underlying mechanisms for gender difference in survival remain unclear. Organ size and functional reserve as well as immunologic, hormonal and mechanical factors may play a role [17]. Further studies are needed before gender matching should be introduced in current lung-allocation systems.

BOS was found to be a strong negative predictive factor for survival on univariate and multivariate analysis. Longer ICU and hospital stay were risk factors of inferior survival on univariate, but not multivariate analysis.

Two studies have specifically looked at the outcome of paired SLTx from the same donor [18,19]. In the first study reported by Snell and colleagues, no differences in ICU and hospital stay, airway complications, and 5-year survival were found. However, an increased mortality was observed in the first 2 years after L-SLTx [18]. In the second study analyzing data from Eurotransplant, no differences were found in hospital outcome, but an inferior survival at 1 year was also seen in L-lung recipients when the retrieval team was different from the transplanting team [19]. Our study with a large majority of non-paired recipients does not support the findings from both these studies.

Although SLTx is a valid therapeutic option for patients suffering from non-suppurative lung diseases, such as emphysema or fibrosis, we now prefer to replace both native lungs by allografts in the vast majority of our patients. It has become clear from the data in the ISHLT Registry that BLTx in these patients is associated with better long-term survival compared with SLTx, a finding now corroborated by many groups [4,5,14,20], including ours [21]. Improved long-term survival after BLTx in patients with emphysema may in part be due to the lower rates of BOS and a longer decline in pulmonary function over time once BOS develops [22]. Patients after SLTx do not tolerate BOS so well. Moreover, single-lung recipients are prone to specific complications in the native lung, such as the development of pneumothorax, hyperinflation with compression of the transplanted lung, and opportunistic infections, especially with Aspergillus and Mycobacterium species, that may jeopardize long-term survival [23]. Patients with smoking-induced emphysema as well as those with pulmonary fibrosis have an increased risk to develop a bronchial carcinoma in the remaining lung [23,24]. Pneumonectomy of the native lung may then be a treatment strategy with the hope to prolong survival in these patients, as was the case in two patients in our series [24]. As demonstrated in Table 1, our transplant group has gradually moved from SLTx to BLTx, with now nearly 90% of our recipients receiving two donor lungs. SLTx is now reserved for patients mainly with pulmonary fibrosis and who are older than 60 years [5]. A recent analysis of the UNOS database has shown that survival after BLTx and SLTx was comparable in patients 60 years of age and older [25]. According to the ISHLT 2010 Report, nearly 65% of patients with COPD and 50% with pulmonary fibrosis currently undergo BLTx [1]. This can be explained by the fact that the choice for SLTx in patients with non-suppurative disease in many transplant centers worldwide is often guided by the shortage of donor lungs and the desire to transplant two rather than one recipient [9].

The present study suffers from several limitations. First, this is a retrospective analysis including data collected over a long time period (from 1991 until 2009). Our donor lung-acceptance criteria, lung-preservation protocol and surgical techniques, and recipient management have undergone significant changes over time with more experience accrued. Second, the indication for SLTx has changed significantly over the years, with more younger patients now being transplanted with two donor lungs; hence, the median age of our SLTx cohort has increased and experience with SLTx has decreased over the years. It is well known that older recipient age will affect survival results [1]. As there was no large discrepancy in the number of L- versus R-SLTx over the years, it is unlikely that these changes have influenced the negative findings in our study. Finally, there was an imbalance between sides, according to the indication (emphysema vs fibrosis), as a result of our preferred transplant side. To exclude or to minimize a selection bias, a matched analysis using propensity score would have been helpful to maximize the information obtained from this study.

In conclusion, the preferred side in SLTx for non-suppurative disease in our transplant cohort differed according to the indication. We did not find a difference in early and late outcome as well as in post-transplant pulmonary function between L- versus R-lung recipients. Survival after SLTx was superior in female recipients, whereas the presence of BOS was a strong negative predictor. Mismatch for perfusion did not influence survival after SLTx. Therefore, besides surgical considerations in the recipient, a donor lung offer opposite to the preferred side should not be a reason to postpone the transplantation until a better-matched donor is found.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the help from our transplant coordinators (Dirk Claes, Stijn Dirix, Joachim de Roey, Bruno Desschans, and Glen Van Helleputte) in collecting donor data.

We would like to thank Professor Dr L. Dupont for his expert help in data analysis and Professor Dr T. Lerut for heading the Department of Thoracic Surgery at the University Hospitals Leuven during the study period.

References

Author notes

Presented at the 18th European Conference on General Thoracic Surgery, Valladolid, Spain, May 30–June 2, 2010.

Funding: Dirk Van Raemdonck is a senior clinical investigator supported by the Fund for Research-Flanders (G.3C04.99).