-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Laura De Michieli, Giulio Sinigiani, Stefano Nistri, Alberto Cipriani, Echocardiographic red flags in transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy: all that glitters is not gold, European Heart Journal - Imaging Methods and Practice, Volume 2, Issue 3, July 2024, qyae114, https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjimp/qyae114

Close - Share Icon Share

This editorial refers to ‘Echocardiographic red flags of ATTR cardiomyopathy a single centre validation’, by M.Y. Henein et al., https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjimp/qyae105

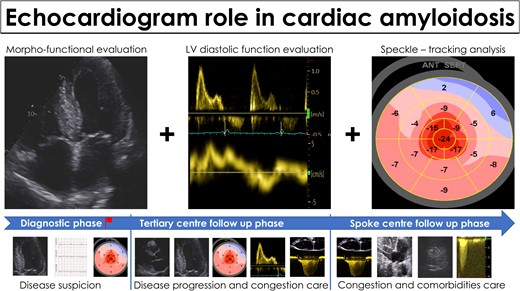

Transthyretin-related amyloid cardiomyopathy (ATTR-CM) has gained significant attention in recent years due to improved diagnostic techniques, increased awareness, and effective treatments.1 Patients previously diagnosed with ‘hypertensive heart disease’, or other definitions suitable for describing their left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), are now correctly identified as affected by ATTR-CM and can therefore be treated accordingly. Regardless of the diagnostic pathway that leads to a final diagnosis of ATTR-CM,2 echocardiography is frequently the first tool that allows clinicians to raise suspicion of the disease. Indeed, echocardiography plays a crucial role in identifying potential cases through various ‘red flags’ that have been investigated for diagnostic purposes in amyloid CM.3–7 Furthermore, echocardiography is the mainstay imaging technique for patients’ follow-up, both in referral centres and spoke cardiology clinics (Figure 1).

Echocardiography in the management of patients with cardiac amyloidosis. Echocardiography is the mainstay imaging technique for disease suspicion and for follow-up both in referral centres and in spoke cardiology clinic.

In this issue of the European Heart Journal—Imaging Methods and Practice, Henein et al. from Umeå University performed a validation study of the most frequently reported echocardiographic red flags for the diagnostic suspicion of ATTR-CM. They included 118 patients with ATTR-CM (mostly affected by hereditary ATTR-CM, only 28 with the non-hereditary or wild-type form, ATTRwt-CM) having interventricular septum > 12 mm, 31 patients with LVH, and 58 healthy controls. Among the multiple variables investigated, relative apical sparing (RELAPS) > 1, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) > 50%, and relative wall thickness (RWT) > 0.6 emerged as the most accurate to support the diagnosis of ATTR-CM. The authors have to be congratulated for their efforts to provide a further contribution analysing several echocardiographic red flags for the diagnostic suspicion of ATTR-CM. However, these results warrant further examination.

One primary aspect to consider, as noted by the authors, is that the population studied is highly selected, comprising primarily patients with hereditary ATTR-CM, which is currently the less common form, even in most referral centres. Additionally, the majority of them carried the Val30Met variant, which may be associated with specific neurological and mixed phenotypes.8 Considering also the previously demonstrated differences in LV structure and function between the subtypes of ATTR-CM,9 applying the present study’s findings to other cohorts should be approached with caution.

Secondly, the predictive value of tested variables is influenced by the prevalence of the disease in a specific cohort. In the present study, the diagnostic performance of the echocardiographic red flags was tested against a smaller cohort of healthy controls and patients with LVH, with a final diagnosis rate of ATTR-CM of 57%. Patients with LVH had various causes for their increased LV thickness (including valve disease and five patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy) and various degrees of functional impairment as expressed by the New York Heart Association class. Healthy controls, who were controls for a previous study, were not affected by LVH. Multiple echocardiographic red flags have been studied over the years for diagnostic purposes in amyloid CM and they have been proven to be highly accurate in selected cohorts with a high prevalence of amyloid CM. However, as we delve deeper into the application of these red flags, we must consider their strengths and limitations in different clinical settings. For example, the limitations of RELAPS, whose pathological basis is still a matter of investigation,10 were recently underlined in a study by Cotella et al.11; the authors showed that RELAPS did not prove to be a specific biomarker for accurate identification of amyloid CM, when compared with clinically similar controls with amyloid CM. Moreover, in a broad population of patients undergoing echocardiogram for various reasons, RELAPS increased the likelihood of amyloid CM diagnosis but with modest sensitivity and specificity.12 In another monocentric study, RELAPS was observed in almost half of patients with aortic stenosis without cardiac amyloidosis, with clear consequences on its value as a screening parameter.13 Indeed, the utility of these red flags becomes less clear-cut when applied to broader, unselected populations. The specificity of these markers may decrease significantly, potentially leading to false positives and unnecessary further testing.

Third, thanks to the increased medical awareness, patients with ATTR-CM nowadays are diagnosed at earlier stages with improved survival.14 Accordingly, cardiac involvement (expressed by laboratory biomarkers, LVEF, and interventricular septum thickness) is less severe in patients diagnosed in recent years, particularly after 2017.14 Therefore, severely abnormal parameters such as a RWT > 0.6 as previously suggested as part of multiparametric scores3 might be less applicable in patients with milder phenotype due to the earlier course of their disease. The authors of the present paper do not report the years of ATTR-CM diagnosis but, based on the echocardiographic characteristics reported in Table 1, patients appear to have a well-manifested cardiac phenotype overall. So, their findings on the performance of red flags such as RELAPS, RWT, and LVEF should be interpreted in the context of a highly selected population with overt phenotype, with a high rate of ATTR-CM diagnosis, mostly hereditary, and therefore, the reproducibility in different cohorts of contemporary all-comers might be problematic.

Finally, in validating possible echocardiographic red flags, is of paramount importance to properly describe the ‘controls’ patients included in the study, so that the readers can appreciate the potential diagnostic application of such red flags in the specific context. Were the LVH patients also referred for suspected ATTR-CM? It would appear so, given the reported negative scintigraphy findings. Was also light chain amyloidosis properly excluded? The characteristics of this group are somewhat nebulous, making it difficult to define them precisely. Furthermore, including a group of healthy controls also might be controversial and could potentially overinflate the diagnostic accuracy of the selected variables. Such healthy controls were reported as having no cardiovascular or systemic disease or taking no medications known to influence cardiac function.15 However, 14% had left atrial enlargement and EF/global longitudinal strain (GLS) > 4, 2% had GLS < −13%, and cardiac index was <2.5 L/min/m2 in 12%. Again, a more thorough understanding of the control groups’ characteristics would have provided greater insight into the applicability of the results.

In conclusion, we surely need accurate and easy red flags to be applied in every Echo-Lab, particularly in primary care, to enhance the possibility of early diagnosis of ATTR-CM and a quick referral for specific therapy. However, we should be mindful that all that glitters is not gold. The applicability of echocardiographic red flags, derived and tested in highly selected cohorts, has been shown to be less attractive if used as screening tools or applied in more heterogeneous cohorts. Moreover, patients in their earlier course of the disease might lack some of the typically described red flags such as RELAPS or severely abnormal RWT. With the availability of approved and experimental therapies, we cannot afford to miss the correct diagnosis in patients with an earlier clinical course and a less advanced phenotype. It is crucial, therefore, to approach the use of echocardiographic red flags with nuance. Even though they represent an essential tool in our diagnostic repository, their application should be tailored to the clinical scenario specific for each patient. As per every medical imaging technique, the overall clinical pre-test probability of disease is of utmost importance. In high-risk populations, echocardiographic red flags can be useful as screening tools. However, in broader and less selected cohorts with lower risk, they should be mindfully used as part of a more comprehensive multiparametric approach and along with other clinical red flags, such as carpal tunnel syndrome, lumbar spinal stenosis, persistently elevated cardiac biomarkers,16 conduction disorders and discrepancy between voltage amplitude and degree of hypertrophy,17 and/or peripheral neuropathy.

Funding

None declared.

Data availability

No new data were generated or analysed in support of this research.

Lead author biography

Laura De Michieli, MD, PhD, graduated in Medicine and Surgery at the University of Padova, where she also completed her Cardiology fellowship. Thereafter, she completed her PhD course in Translational Specialistic Medicine G.B. Morgagni at the University of Padova. She is now assistant Professor at the Department of Cardiac, Thoracic, Vascular Sciences and Public Health, University of Padova. She is a clinical cardiologist; her main interests are rare cardiac conditions (such as cardiac amyloidosis, Anderson-Fabry disease and pulmonary arterial hypertension) as well as the use of cardiac biomarkers in these and other heart diseases.

References

Author notes

The opinions expressed in this article are not necessarily those of the Editors of EHJ-IMP or the European Society of Cardiology.

Conflict of interest: L.D.M. has received honoraria from Pfizer Inc., Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca Spa, Takeda Pharmaceutical, and Sanofi. G.S. received travel support from Pfizer Inc. and Alnylam Pharmaceuticals. A.C. received honoraria from Pfizer Inc., Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca Spa, and Bayer.