-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Thomas A Slater, Michael Drozd, Victoria Palin, Charlotte Bowles, Mohammed A Waduud, Rani Khatib, Ramzi A Ajjan, Stephen B Wheatcroft, Prescribing diabetes medication for cardiovascular risk reduction in patients admitted with acute coronary syndromes: a survey of cardiologists’ attitudes and practice, European Heart Journal - Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy, Volume 6, Issue 3, May 2020, Pages 194–196, https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjcvp/pvz058

Close - Share Icon Share

Diabetes is a potent cardiovascular risk factor which affects around one-quarter of patients admitted with acute coronary syndromes (ACS) and is associated with impaired clinical outcomes.1 In the absence of clear evidence for improved macrovascular outcomes with intensive glycaemic modulation,2 cardiologists have traditionally focused on lipid modification, blood pressure lowering, and anti-platelet therapy to reduce the risk of adverse cardiovascular events in patients with diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Recently, a significant shift in the landscape of cardiovascular risk management has followed the publication of a series of cardiovascular outcome trials, in which sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists demonstrated reduced risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, and stroke) when added to standard of care in patients with type 2 diabetes who have cardiovascular disease.3–5

Recent international guidelines and consensus statements prioritize SGLT2i and GLP-1 receptor agonists as strategies to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events in patients with established cardiovascular disease.6–8 Furthermore, these consensus statements suggest that cardiologists should play a key role in identifying appropriate patients and initiating treatment.6,7

Recognizing that there is often a lag phase between guideline recommendations and clinical implementation and that not all cardiologists may be comfortable with initiating glucose-lowering therapy, we conducted a questionnaire survey of consultant cardiologists’ knowledge, attitudes, and willingness to prescribe diabetes medication in patients hospitalized with ACS: a clinical setting in which there are well-developed and robust mechanisms through which cardiologists routinely address other aspects of cardiovascular risk reduction.

An online survey (created using www.onlinesurveys.ac.uk) was disseminated by email to consultant cardiologists practicing in the United Kingdom National Health Service (NHS) between March and July 2019. Cardiologists were identified through the hospital consultant search facility of the NHS website (https://www.nhs.uk/Service-Search/Hospital/LocationSearch/8/Consultants). Email addresses were matched using the NHSmail portal (www.nhs.net). The survey was approved by the School of Medicine Research Ethical Committee, University of Leeds.

One hundred and three survey responses were received from cardiologists working across seven cardiology sub-specialties (11% total response rate) (Figure 1A). Regarding assessment of glycaemic control, 29% (n = 30) measured HbA1c in all patients with ACS, while 54% (n = 56) measured HbA1c in most patients (Figure 1B). If HbA1c was measured during the index admission, 69% (n = 70) would act on the results and 14% (n = 14) would defer action to primary care (Figure 1C).

Subspecialty breakdown of survey respondents and screening for diabetes, assessing glycaemic control and subsequent actions. (A) Subspecialty breakdown. (B) Do all your acute coronary syndromes patients have HbA1c/fasting glucose checked during the index admission? If HbA1c/fasting glucoses are requested, during the hospital admission are results routinely (C).

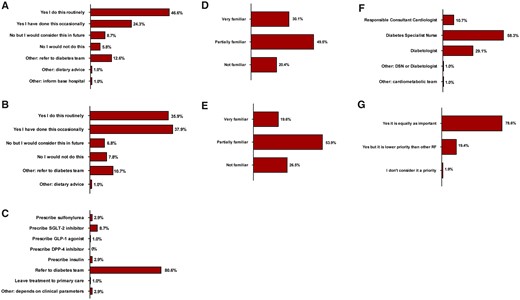

Diabetes medication was initiated if clinically indicated by 47% (n = 48) of respondents (Figure 2A). The majority indicated they either routinely (36%; n = 37) or occasionally (38%; n = 39) up-titrated existing medication (Figure 2B). However, when given treatment options, 81% (n = 83) indicated they would refer to a diabetes team in preference to initiating medication themselves (Figure 2C).

Initiation and titration of glucose-lowering medications by cardiologists; cardiologist awareness of evidence base for sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists; cardiologists’ opinions on who should be responsible for implementation of diabetes therapy after acute coronary syndrome. (A) If a patient has newly diagnosed diabetes post-acute coronary syndromes, would you consider initiating diabetes medication during the index admission if drug treatment is indicated? (B) If a patient has known diabetes and a treatment change is indicated, would you consider uptitrating an existing medication during the index admission? (C) If an acute coronary syndromes patient with diabetes has sub-optimal glycaemic control on metformin alone, during their hospital admission would you… (D) Are you aware of the cardiovascular outcome data associated with sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors? (E) Are you aware of the cardiovascular outcome data associated with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists? (F) Who do you think is best suited to deliver diabetes treatment for an in-patient post-acute coronary syndromes? (G) Overall, do you feel diabetes management is a priority in acute coronary syndromes patients?

We also set out to establish respondents’ knowledge of the beneficial cardiovascular outcomes of SGLT2i and GLP-1 receptor agonists. Only a minority of respondents felt they were very familiar with the outcomes of these trials (30% and 20%, respectively). 20% (n = 21) and 27% (n = 27) of respondents admitted that they were not familiar with trial data for SGLT2i and GLP-1 receptor agonists, respectively (Figure 2D and E).

Finally, only 11% (n = 11) of respondents felt it was their responsibility to deliver diabetes therapy for inpatients following ACS. The overwhelming majority of respondents felt that therapy delivery should be deferred to the specialist diabetes team, whether that be a diabetes specialist nurse (58%; n = 60) or diabetologist (29%; n = 30) (Figure 2F). 79% (n = 81) of respondents agreed that diabetes management is a priority in ACS management and is as important as other risk factors (Figure 2G).

There are several potential reasons for the apparent reluctance of cardiologists to implement evidence-based risk reduction therapy in type 2 diabetes. First, our survey demonstrated lack of familiarity with SGLT2i and GLP-1 receptor agonist trial outcomes. Awareness of these drugs is likely to increase amongst cardiologists following the release of results from The Dapagliflozin And Prevention Of Adverse-outcomes In Heart Failure Trial (DAPA-HF), after the survey was completed, indicating reduction of heart failure events and cardiovascular mortality in patients both with and without diabetes treated with dapagliflozin.9 It is likely that trials such as DAPA-HF will transition SGLT2i from being perceived as ‘diabetes’ drugs to being considered ‘cardiometabolic’ drugs by cardiologists, leading to increased awareness and greater willingness to prescribe. New European Society of Cardiology Guidelines on Diabetes, Pre-diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease, also published after this survey was conducted, provide practical algorithms for implementation by cardiology teams.8 Second, there is often a lag phase between publication of primary evidence for new therapies, recommendations in consensus guidelines and widespread clinical implementation.10 Third, there may be a perception amongst cardiologists that prescribing glucose-lowering therapy is outside of their remit. Fewer than one in ten respondents to our survey considered the cardiologist to be best suited to delivery of diabetes therapy in acute coronary syndrome. This is surprising given the high take up of other aspects of risk modification by cardiologists and the magnitude of benefit conferred by these drugs.4,5

Although our survey provides a valuable insight into cardiologists' practice and perceptions of prescribing diabetes therapy, it is important to note potential limitations. Not all cardiologists responded to the invitation to complete the questionnaire which may have led to response bias favouring cardiologists with an interest in diabetes. Our survey was undertaken in the UK and the results may not be generalizable to other countries in which clinical practices and clinicians’ attitudes may differ.

In summary, our survey is the first to assess knowledge and attitudes of cardiologists towards prescribing diabetes therapy in ACS and provides important insights into the feasibility of widespread adoption of guideline implementation by cardiologists in this setting. Raised awareness and attitudinal change may be required for cardiologists to prescribe more widely. Ultimately, optimum management of patients with diabetes and cardiovascular disease may be best served by collaborative working between cardiology, diabetes, and primary care teams.

Funding

T.A.S., M.D., and M.A.W. are funded by British Heart Foundation Clinical Research Training Fellowships. S.B.W. is supported by research grants from the British Heart Foundation and the European Research Council.

Conflict of interest: S.B.W. has received honoraria from Bayer, AstraZeneca, Servier, and Boehringer Ingelheim. R.A.A. received institutional research grants from Abbott, Bayer, Eli Lilly, NovoNordisk, Roche, and Takeda. He also received honoraria/education support/consultancy from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Sharp & Dohme, NovoNordisk, Takeda. R.K. received one or more of the following: educational & research grants and speaker fees from AstraZeneca, NovoNordisk and MSD. T.A.S, M.D., V.P., C.B. and M.A.W. have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes Study Group,