-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Julia W. Erath, Mate Vamos, Stefan H. Hohnloser, Effects of digitalis on mortality in a large cohort of implantable cardioverter defibrillator recipients: results of a long-term follow-up study in 1020 patients, European Heart Journal - Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy, Volume 2, Issue 3, July 2016, Pages 168–174, https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjcvp/pvw008

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The effects of digitalis on mortality in patients with structural heart disease are controversially discussed. We aimed to assess the effects of digitalis administration in implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) recipients.

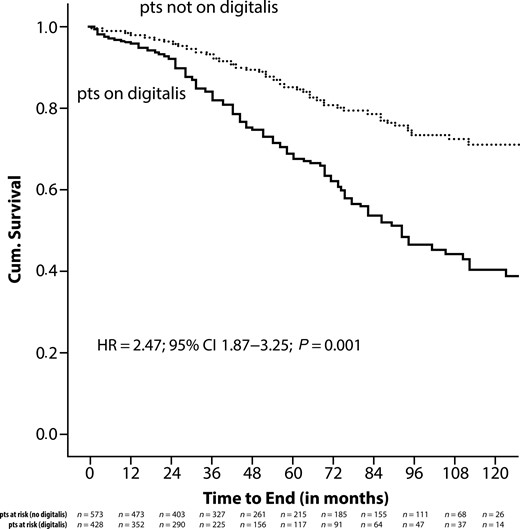

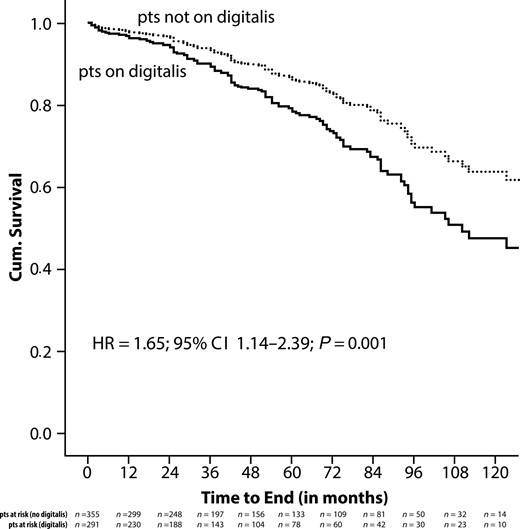

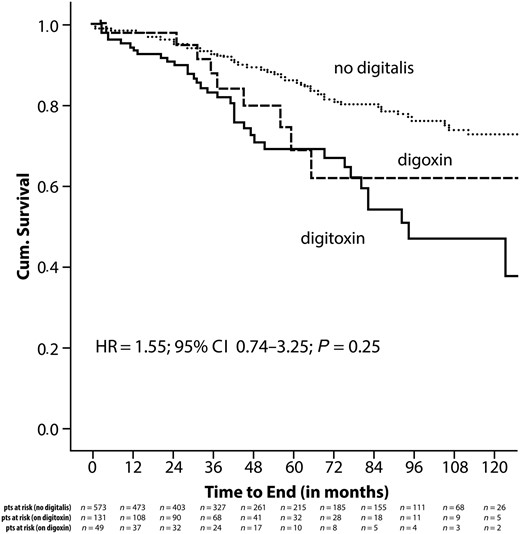

This retrospective analysis comprises 1020 consecutive patients who received an ICD at our institution and who were followed for up to 10 years (median 37 months). A total of 438 patients were receiving digitalis at the time of ICD implantation and 582 did not. Patients on digitalis were more often in atrial fibrillation and had more often a prolonged QRS duration of ≥120 ms, a severely impaired left ventricular ejection fraction, and higher New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification heart failure. Crude Kaplan–Meier analysis demonstrated significantly higher mortality in patients on digitalis (HR = 2.47; 95% CI 1.87–3.25; P = 0.001). After adjustment for patient characteristics found statistically significant in adjusted Cox regression analysis (age, gender, NYHA classification, and QRS duration of ≥120 ms), a HR of 1.65 remained (95% CI 1.14–2.39; P = 0.01). Patients on digitalis died more often from cardiac arrhythmic and cardiac non-arrhythmic causes than patients not on digitalis (P = 0.04). There was no difference in mortality between patients receiving digitoxin and those receiving digoxin (HR = 1.55; 95% CI 0.74–3.25; P = 0.25).

In this large ICD patient population, digitalis use at baseline was independently associated with increased mortality even after careful adjustment for possible confounders. Digitalis should be used with great caution in this population.

Introduction

Digitalis is used to treat patients with symptomatic heart failure and/or with atrial fibrillation (AF) to control their ventricular rate.1–3 There is only one randomized trial evaluating the effects of digitalis compared with placebo in patients with heart failure and impaired left ventricular function who were in sinus rhythm, the so-called DIG trial.4 This trial failed to show a reduction in mortality in patients allocated to active therapy, but digitalis was associated with a lower hospitalization rate compared.4 Based on these results, current guidelines recommend digitalis use as a Class IIb indication for the treatment of symptomatic heart failure in order to reduce hospitalization.1,2 In addition, there is a Class IIa indication for digitalis to establish rate control in patients with AF,3 although there is no randomized placebo-controlled trial supporting this recommendation. Digitalis is commonly used despite its narrow therapeutic window and its potential for drug–drug interactions.5 A post hoc analysis of the DIG trial showed that it is of paramount importance to maintain low digitalis plasma concentrations to avoid harmful effects on mortality.6 Since the publication of the DIG trial, many pro- and retrospective studies raised concerns in terms of the safety of digitalis when used in patients who were otherwise treated with contemporary medications.7–11 A recent comprehensive meta-analysis of 19 studies found an increased relative risk of all-cause mortality (HR = 1.21; 95% CI 1.07–1.38; P = 0.01) in subjects treated with digitalis when compared with those not receiving this medication.12 There is a lack of data concerning the use of digitalis in implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) patients. A recent subgroup analysis from MADIT-CRT showed an increased risk of high-rate ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation (VT/VF) episodes in patients treated with digitalis, but no difference in mortality.13 Hence, the present study evaluated the effects of digitalis use in a large series of consecutive ICD recipients for the prevention of sudden cardiac death and who were followed for up to 10 years.

Methods

Patient population

This retrospective observational study is based on the analysis of data collected in consecutive patients who received an ICD or a cardiac resynchronization device (CRT-D) at the J.W. Goethe University Frankfurt between 1996 and 2010 and who were followed at the same institution. Devices from various manufacturers were used (Medtronic, USA; St Jude Medical/Ventritex, USA; Guidant/Boston Scientific, USA; ELA/Sorin, Italy). The study was approved by the institutional review board of the J.W. Goethe University and conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

Data collection

Data were prospectively collected from the index hospitalization at the time of initial ICD implantation and at each follow-up visit that took place every 6 months or at the time of unscheduled visits in the out- or inpatient clinic. Data collection included patient characteristics such as age and race, the initial indication for ICD as well as the type of device implanted (single-, dual, or triple-chamber ICD), the most recent left ventricular ejection fraction, and relevant co-morbid conditions. Pertinent medication use (β-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, digitalis glycosides, antiarrhythmic drugs) was documented. Digitalis was used to treat heart failure and/or to control heart rate in AF, according to current guideline recommendations.1–3 Data were also collected from device interrogations. All relevant information was entered into a customized database (Microsoft Access 5 or Microsoft Excel). For missing data, particularly in case of missed follow-up visits, family members, treating physicians, or other hospitals were contacted to retrieve the missing information.

Outcomes

The primary outcome measure was time to all-cause mortality. Cause-specific mortality was defined according to the Hinkle and Thaler classification.14

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 22 program (IBM, USA). Baseline characteristics were compared by the Wilcoxon Mann–Whitney U test (continuous variables) and the χ2 test or Fisher exact test (categorical variables). Survival analysis was performed using Kaplan–Meier analysis. Survival curves were compared using the log-rank test and Wald test for the Cox proportional hazard model. Crude and adjusted hazard ratios (HR) with 95% CI for digitalis use were calculated for potential confounding factors including age, gender, primary/secondary prevention indication, ischaemic/non-ischaemic heart disease, New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), ICD type, QRS width, documented AF, diabetes mellitus, and chronic renal disease. Independent predictors of mortality were derived by backward stepwise variable selection using Wald test in the multivariate Cox regression model. Only two-sided tests were used, and P-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient population

A total of 1448 patients underwent ICD implantation at our institution from 1996 to 2010 for primary or secondary prevention of sudden cardiac death. Of those, 1020 were regularly followed-up in our ICD outpatient clinic and form the basis of this report. Of these, 561 (55%) received a single-chamber ICD, 295 (29%) a dual-chamber device, and 159 (16%) a CRT-D. The follow-up period ranged between 10 and 209 months (median 37 months).

Our patient cohort consisted of a typical ICD population with a mean age of 63 years, male preponderance (79%), and ischaemic heart disease (68%) as the predominant underlying structural heart disease (Table A1).

At ICD implantation, 438 patients (43%) were receiving digitalis glycosides. Digitalis medication was prescribed either for the treatment of congestive heart failure or for the control of ventricular rate in AF, or for both conditions. Patients treated with digitalis were older (median 63 years), were more often in AF (21 vs. 10%; P < 0.001), and had worse left ventricular function (mean LVEF 26%) than patients not treated with digitalis (mean LVEF 38%; P < 0.001). Intraventricular conduction disturbances with a QRS duration of ≥120 ms were present in 47% of digitalis patients and in 33% of those without this medication. Patients on digitalis had significantly more co-morbidities such as diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney failure (P < 0.001) (Table A1).

All-cause mortality

During the observation period, 213 patients died, 128 treated with digitalis at baseline, and 85 not receiving this medication. Crude Kaplan–Meier survival analysis demonstrated a significantly higher mortality in patients who received digitalis at the time of ICD implantation compared with those not on this medication (HR = 2.47; 95% CI 1.87–3.25; P = 0.001) (Figure A1). To correct for potential confounders, Kaplan–Meier analysis was repeated with data adjusted for all variables found significantly different between both patient groups in a multivariate analysis. These independent predictors of mortality were age, male gender, NYHA classification, and prolonged QRS duration. After adjustment, the risk for death continued to be higher among patients on digitalis compared with subjects not receiving digitalis (HR = 1.65; 95% CI 1.14–2.39; P = 0.01) (Figure A2). We performed a subgroup analysis of patients with ischaemic heart disease and of patients with non-ischaemic heart disease and the effects of digitalis on mortality. In patients with ischaemic heart disease, the HR was 1.67 (95% CI 1.09–2.54; P = 0.02) compared with a HR of 2.15 (95% CI 0.90–5.16; P = 0.09) in patients with non-ischaemic heart disease.

Cause-specific mortality

In 69 of 213 patients, cause-specific mortality according to the Hinkle and Thaler classification14 could not be assessed due to missing detailed information surrounding circumstances of death. Among patients receiving digitalis, 37% suffered from cardiac arrhythmic, 24% from cardiac non-arrhythmic, and 11% from non-cardiac death. Respective numbers for patients not on digitalis were 32% (P = 0.044), 19% (P = 0.036), and 12% (P = n.s.). Subsequently, more ICD shocks occurred in patients on digitalis compared with patients not on digitalis (HR = 1.30; 95% CI 0.93–1.80). For appropriate shocks, the HR was 1.74 (95% CI 1.14–2.65), and for inappropriate shocks, a HR of 0.92 (95% CI 0.56–1.51) was found.

Digoxin/digitoxin

Two different digitalis preparations were used in our patient population and could be retrieved in most of the patients (96% of digitalis patients; Table A3). The majority of the patients received digitoxin (n = 306 patients). Digoxin was prescribed to 105 patients. The median prescribed daily dosages were in the recommended range (digitoxin: 0.035–0.10 mg/day; digoxin 0.05–0.20 mg/day). Plasma concentrations of digoxin (normal range at our institution: 0.8–2.0 μg/L) or digitoxin (normal range at our institution: 10.0–30.0 μg/L) at any time during follow-up could be retrieved by chart review in 220 patients (50%). In these patients, mean digoxin plasma concentration was 0.8 μg/L, and mean digitoxin plasma concentration was 21.6 μg/L. Concerning all-cause mortality, there was no difference between patients treated with digitoxin and patients treated with digoxin (HR = 1.55; 95% CI 0.74–3.25; P = 0.25) (Figure A3).

Discussion

Main findings

The main finding of this study is that digitalis was associated with an increased risk of death in patients receiving an implantable defibrillator. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that such an association is described in a single-centre cohort study of consecutive ICD recipients treated according to contemporary guideline recommendations.1–3 A second noteworthy finding is that the type of digitalis preparation—digoxin vs. digitoxin—carries a similar risk of mortality.

Effects of digitalis on mortality

Digitalis glycosides are used to treat congestive heart failure in patients with reduced left ventricular function1,2 and in AF to control the ventricular rate.3 Of note, these recommendations are based upon the results of a single randomized placebo-controlled trial.4 This trial conducted exclusively in patients in sinus rhythm demonstrated a neutral effect of digitalis on mortality but a 28% risk reduction for heart failure hospitalization. Of note, the trial was conducted at a time when β-blockade and the use of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists were not yet part of modern heart failure therapy. Since the publication of the DIG trial,4 numerous more contemporary reports in patients with heart failure or AF have described increased risk of mortality in patients receiving digitalis.7–11,15–17 In one of the largest of these studies, Shah et al. found in 27 972 heart failure and in 46 262 AF patients a hazard ratio of 1.14 and 1.17 for mortality, respectively, in digitalis-treated patients.15 Similarly, in a recent post hoc analysis of the randomized ROCKET-AF trial in 14 171 patients with AF, the use of digitalis was associated with a 17% increase in the risk of mortality.17 Our present findings are in line with these reports and extend the observations on digitalis to the population of ICD recipients. By multivariate analysis, digitalis was an independent predictor of death next to other established risk factors. Crude Kaplan–Meier survival analysis demonstrated a 2.5-fold increased mortality risk in subjects treated with digitalis. In order to minimize potential confounding, this analysis was repeated after careful adjustment for known risk factors of mortality in ICD recipients. This adjusted analysis continued to demonstrate a 1.7-fold increased risk. Finally, support for the detrimental effects of digitalis stems from a recent comprehensive meta-analysis of 19 reports including data from >325 000 patients.12 In this analysis, we could demonstrate a hazard ratio for all-cause mortality of 1.21 in subjects receiving digitalis with a particularly higher risk in AF patients (HR = 1.29; 95% CI 1.21–1.39).12

Cause-specific mortality

The most common causes of death in heart failure patients treated with digitalis are cardiac arrhythmic or cardiac non-arrhythmic deaths due to pump failure.4,10 This was confirmed in the present study, where patients on digitalis therapy died predominantly from cardiac arrhythmic and cardiac non-arrhythmic deaths (P = 0.044; P = 0.036). These findings are endorsed by a recent published subgroup analysis of the MADIT-CRT collective demonstrating an increased risk of high-rate VT/VF (≥200 b.p.m.) in patients on digitalis.13

Digitalis is a well-known cause of cardiac arrhythmias such as AV conduction disturbances, atrial tachycardias with or without block, and ventricular tachyarrhythmias including torsade de pointes and bidirectional VT.18 Also, patients on digitalis suffered more often from ICD shock therapy, especially appropriate shocks. It remains speculative to which extend such specific arrhythmias have contributed to the observed mortality figures, but delivered ICD shock therapy is known to be an independent predictor of mortality.19,20 Furthermore, digitalis works physiologically as a positive inotropic agent with its intensity depending on the plasma concentration.21,22 Other inotropes such as milrinone have also been afflicted with increased mortality rates in patients with severe congestive heart failure.23 In support of our findings, a retrospective analysis of the ROCKET-AF trial showed that—after adjustment—digoxin was associated with increased all-cause mortality (HR = 1.17; 95% CI 1.04–1.32; P = 0.01), vascular death (HR = 1.19; 95% CI 1.03–1.39; P = 0.02), and sudden death (HR = 1.36; 95% CI 1.08–1.70; P = 0.01).17

Digoxin, digitoxin, and digitalis plasma concentrations

A post hoc analysis of the DIG trial showed that there was an association between digitalis plasma levels and mortality.6 In the subgroup of patients with digoxin concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 0.8 ng/mL, there was a mortality benefit, whereas in subjects with higher digoxin concentrations, mortality was increased.6 The majority of our patients was treated after the publication of this analysis, hence physicians aimed to adhere to low digitalis plasma concentrations. Due to the retrospective nature of our study, we had digitalis plasma concentrations available only in 50% of patients. These data, however, showed that for the majority mean plasma concentration tended to be in the low range. Similar observations were made regarding prescribed mean daily dosages of digitalis.

Limitations of the study

Our study is retrospective in nature, hence all potential limitations of such a design apply to this analysis. This needs to be considered for interpreting the main findings of the study and also for the mortality verification [i.e. arrhythmic or (non-)cardiac death]. We aimed to minimize potential confounding by carefully adjusting data to important patient characteristics found on univariate and multivariate analysis. Despite this, residual confounding cannot be entirely excluded. Digitalis use was assessed at ICD implantation but not during follow-up or at time of death. Digitalis serum concentrations were not controlled in fixed intervals. Data on the type of digitalis used were not available for 50% of the population. Strengths of our study consist of the large patient cohort, the long follow-up duration, and the consistency with recently published data from a comprehensive meta-analysis.12

Conclusions

In this large population of consecutive ICD recipients undergoing long-term follow-up observation, digitalis was independently associated with increased mortality. In addition, there was no difference in the mortality risk between patients treated with digitoxin or with digoxin. Digitalis should therefore be used with great caution in clinical practice. Randomized placebo controlled trials of digitalis use in patients with heart failure are urgently warranted.

Acknowledgements

The statistical expertise of Eva Herrmann, Head of Department of Biostatistics, J.W. Goethe University, and the assistance in the data requisition of Antje Steidl (research nurse) are greatly appreciated by the authors.

Conflict of interest: J.W.E. has nothing to disclose. M.V. reports lecture fee from Pfizer, outside the submitted work. S.H.H. reports receiving consulting fees from Bayer Healthcare, Boehringer Ingelheim, Gilead, J&J, Medtronic, Pfizer, St Jude Medical, Sanofi-Aventis; and lecture fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer Healthcare, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, St Jude Medical, Sanofi-Aventis, and Cardiome, outside the submitted work.

Appendix

| Variables . | All patients (n = 1020) . | Patients on digitalis (n = 438) . | Patients not on digitalis (n = 582) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age mean (SD) (years) | 63 (12) | 63 (11) | 62 (13) | n.s. |

| Male gender, n (%) | 809 (79) | 345 (79) | 464 (80) | n.s. |

| Primary prevention, n (%) | 585 (58) | 251 (57) | 334 (57) | n.s. |

| Secondary prevention, n (%) | 430 (42) | 182 (43) | 248 (43) | |

| Ischaemic heart disease, n (%) | 690 (68) | 288 (66) | 402 (69) | 0.02 |

| Non-ischaemic heart disease, n (%) | 430 (32) | 150 (34) | 248 (43) | |

| NYHA classification, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| 0 + I | 256 (25) | 52 (12) | 204 (35) | |

| II | 348 (34) | 156 (36) | 192 (33) | |

| III | 257 (25) | 167 (38) | 90 (15) | |

| IV | 23 (2) | 16 (4) | 7 (1) | |

| LVEF mean, % (SD) | 33 (13) | 26 (8) | 38 (14) | <0.001 |

| ICD type, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Single chamber | 561 (55) | 233 (53) | 328 (56) | |

| Dual chamber | 295 (29) | 106 (24) | 189 (32) | |

| CRT-D | 159 (16) | 94 (21) | 65 (11) | |

| QRS ≥120 ms, n (%) | 397 (39) | 206 (47) | 191 (33) | <0.001 |

| Documented AF, n (%) | 150 (15) | 94 (21) | 56 (10) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 311 (30) | 169 (39) | 142 (24) | <0.001 |

| Chronic kidney failure, n (%) | 258 (25) | 150 (34) | 108 (19) | <0.001 |

| Variables . | All patients (n = 1020) . | Patients on digitalis (n = 438) . | Patients not on digitalis (n = 582) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age mean (SD) (years) | 63 (12) | 63 (11) | 62 (13) | n.s. |

| Male gender, n (%) | 809 (79) | 345 (79) | 464 (80) | n.s. |

| Primary prevention, n (%) | 585 (58) | 251 (57) | 334 (57) | n.s. |

| Secondary prevention, n (%) | 430 (42) | 182 (43) | 248 (43) | |

| Ischaemic heart disease, n (%) | 690 (68) | 288 (66) | 402 (69) | 0.02 |

| Non-ischaemic heart disease, n (%) | 430 (32) | 150 (34) | 248 (43) | |

| NYHA classification, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| 0 + I | 256 (25) | 52 (12) | 204 (35) | |

| II | 348 (34) | 156 (36) | 192 (33) | |

| III | 257 (25) | 167 (38) | 90 (15) | |

| IV | 23 (2) | 16 (4) | 7 (1) | |

| LVEF mean, % (SD) | 33 (13) | 26 (8) | 38 (14) | <0.001 |

| ICD type, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Single chamber | 561 (55) | 233 (53) | 328 (56) | |

| Dual chamber | 295 (29) | 106 (24) | 189 (32) | |

| CRT-D | 159 (16) | 94 (21) | 65 (11) | |

| QRS ≥120 ms, n (%) | 397 (39) | 206 (47) | 191 (33) | <0.001 |

| Documented AF, n (%) | 150 (15) | 94 (21) | 56 (10) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 311 (30) | 169 (39) | 142 (24) | <0.001 |

| Chronic kidney failure, n (%) | 258 (25) | 150 (34) | 108 (19) | <0.001 |

SD, standard deviation; NYHA, New York Heart Association classification; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; CRT-D, cardiac resynchronization therapy-defibrillator; AF, atrial fibrillation.

| Variables . | All patients (n = 1020) . | Patients on digitalis (n = 438) . | Patients not on digitalis (n = 582) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age mean (SD) (years) | 63 (12) | 63 (11) | 62 (13) | n.s. |

| Male gender, n (%) | 809 (79) | 345 (79) | 464 (80) | n.s. |

| Primary prevention, n (%) | 585 (58) | 251 (57) | 334 (57) | n.s. |

| Secondary prevention, n (%) | 430 (42) | 182 (43) | 248 (43) | |

| Ischaemic heart disease, n (%) | 690 (68) | 288 (66) | 402 (69) | 0.02 |

| Non-ischaemic heart disease, n (%) | 430 (32) | 150 (34) | 248 (43) | |

| NYHA classification, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| 0 + I | 256 (25) | 52 (12) | 204 (35) | |

| II | 348 (34) | 156 (36) | 192 (33) | |

| III | 257 (25) | 167 (38) | 90 (15) | |

| IV | 23 (2) | 16 (4) | 7 (1) | |

| LVEF mean, % (SD) | 33 (13) | 26 (8) | 38 (14) | <0.001 |

| ICD type, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Single chamber | 561 (55) | 233 (53) | 328 (56) | |

| Dual chamber | 295 (29) | 106 (24) | 189 (32) | |

| CRT-D | 159 (16) | 94 (21) | 65 (11) | |

| QRS ≥120 ms, n (%) | 397 (39) | 206 (47) | 191 (33) | <0.001 |

| Documented AF, n (%) | 150 (15) | 94 (21) | 56 (10) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 311 (30) | 169 (39) | 142 (24) | <0.001 |

| Chronic kidney failure, n (%) | 258 (25) | 150 (34) | 108 (19) | <0.001 |

| Variables . | All patients (n = 1020) . | Patients on digitalis (n = 438) . | Patients not on digitalis (n = 582) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age mean (SD) (years) | 63 (12) | 63 (11) | 62 (13) | n.s. |

| Male gender, n (%) | 809 (79) | 345 (79) | 464 (80) | n.s. |

| Primary prevention, n (%) | 585 (58) | 251 (57) | 334 (57) | n.s. |

| Secondary prevention, n (%) | 430 (42) | 182 (43) | 248 (43) | |

| Ischaemic heart disease, n (%) | 690 (68) | 288 (66) | 402 (69) | 0.02 |

| Non-ischaemic heart disease, n (%) | 430 (32) | 150 (34) | 248 (43) | |

| NYHA classification, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| 0 + I | 256 (25) | 52 (12) | 204 (35) | |

| II | 348 (34) | 156 (36) | 192 (33) | |

| III | 257 (25) | 167 (38) | 90 (15) | |

| IV | 23 (2) | 16 (4) | 7 (1) | |

| LVEF mean, % (SD) | 33 (13) | 26 (8) | 38 (14) | <0.001 |

| ICD type, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Single chamber | 561 (55) | 233 (53) | 328 (56) | |

| Dual chamber | 295 (29) | 106 (24) | 189 (32) | |

| CRT-D | 159 (16) | 94 (21) | 65 (11) | |

| QRS ≥120 ms, n (%) | 397 (39) | 206 (47) | 191 (33) | <0.001 |

| Documented AF, n (%) | 150 (15) | 94 (21) | 56 (10) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 311 (30) | 169 (39) | 142 (24) | <0.001 |

| Chronic kidney failure, n (%) | 258 (25) | 150 (34) | 108 (19) | <0.001 |

SD, standard deviation; NYHA, New York Heart Association classification; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; CRT-D, cardiac resynchronization therapy-defibrillator; AF, atrial fibrillation.

| Variables . | All patients (n = 1020) . | Patients on digitalis (n = 438) . | Patients not on digitalis (n = 582) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASA, n (%) | 604 (59) | 243 (55) | 361 (62) | 0.01 |

| Clopidogrel, n (%) | 245 (24) | 120 (27) | 125 (21) | 0.01 |

| Vitamin K antagonist, n (%) | 336 (33) | 193 (44) | 143 (26) | 0.03 |

| Diuretics, n (%) | 700 (69) | 374 (85) | 326 (56) | 0.06 |

| ACE inhibitor, n (%) | 761 (75) | 338 (77) | 423 (73) | n.s. |

| Angiotensin receptor blocker, n (%) | 94 (9) | 48 (11) | 46 (8) | n.s. |

| β-Blocker, n (%) | 873 (86) | 391 (89) | 482 (83) | 0.02 |

| Calcium antagonist, n (%) | 121 (12) | 40 (9) | 81 (14) | n.s. |

| Class 1c antiarrhythmic, n (%) | 7 (1) | 2 (0) | 5 (1) | n.s. |

| Sotalol, n (%) | 58 (6) | 14 (3) | 44 (8) | n.s. |

| Amiodarone, n (%) | 196 (19) | 95 (22) | 101 (17) | n.s. |

| Variables . | All patients (n = 1020) . | Patients on digitalis (n = 438) . | Patients not on digitalis (n = 582) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASA, n (%) | 604 (59) | 243 (55) | 361 (62) | 0.01 |

| Clopidogrel, n (%) | 245 (24) | 120 (27) | 125 (21) | 0.01 |

| Vitamin K antagonist, n (%) | 336 (33) | 193 (44) | 143 (26) | 0.03 |

| Diuretics, n (%) | 700 (69) | 374 (85) | 326 (56) | 0.06 |

| ACE inhibitor, n (%) | 761 (75) | 338 (77) | 423 (73) | n.s. |

| Angiotensin receptor blocker, n (%) | 94 (9) | 48 (11) | 46 (8) | n.s. |

| β-Blocker, n (%) | 873 (86) | 391 (89) | 482 (83) | 0.02 |

| Calcium antagonist, n (%) | 121 (12) | 40 (9) | 81 (14) | n.s. |

| Class 1c antiarrhythmic, n (%) | 7 (1) | 2 (0) | 5 (1) | n.s. |

| Sotalol, n (%) | 58 (6) | 14 (3) | 44 (8) | n.s. |

| Amiodarone, n (%) | 196 (19) | 95 (22) | 101 (17) | n.s. |

ASA, acetyl salicyl acid; ACE inhibitor, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor.

| Variables . | All patients (n = 1020) . | Patients on digitalis (n = 438) . | Patients not on digitalis (n = 582) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASA, n (%) | 604 (59) | 243 (55) | 361 (62) | 0.01 |

| Clopidogrel, n (%) | 245 (24) | 120 (27) | 125 (21) | 0.01 |

| Vitamin K antagonist, n (%) | 336 (33) | 193 (44) | 143 (26) | 0.03 |

| Diuretics, n (%) | 700 (69) | 374 (85) | 326 (56) | 0.06 |

| ACE inhibitor, n (%) | 761 (75) | 338 (77) | 423 (73) | n.s. |

| Angiotensin receptor blocker, n (%) | 94 (9) | 48 (11) | 46 (8) | n.s. |

| β-Blocker, n (%) | 873 (86) | 391 (89) | 482 (83) | 0.02 |

| Calcium antagonist, n (%) | 121 (12) | 40 (9) | 81 (14) | n.s. |

| Class 1c antiarrhythmic, n (%) | 7 (1) | 2 (0) | 5 (1) | n.s. |

| Sotalol, n (%) | 58 (6) | 14 (3) | 44 (8) | n.s. |

| Amiodarone, n (%) | 196 (19) | 95 (22) | 101 (17) | n.s. |

| Variables . | All patients (n = 1020) . | Patients on digitalis (n = 438) . | Patients not on digitalis (n = 582) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASA, n (%) | 604 (59) | 243 (55) | 361 (62) | 0.01 |

| Clopidogrel, n (%) | 245 (24) | 120 (27) | 125 (21) | 0.01 |

| Vitamin K antagonist, n (%) | 336 (33) | 193 (44) | 143 (26) | 0.03 |

| Diuretics, n (%) | 700 (69) | 374 (85) | 326 (56) | 0.06 |

| ACE inhibitor, n (%) | 761 (75) | 338 (77) | 423 (73) | n.s. |

| Angiotensin receptor blocker, n (%) | 94 (9) | 48 (11) | 46 (8) | n.s. |

| β-Blocker, n (%) | 873 (86) | 391 (89) | 482 (83) | 0.02 |

| Calcium antagonist, n (%) | 121 (12) | 40 (9) | 81 (14) | n.s. |

| Class 1c antiarrhythmic, n (%) | 7 (1) | 2 (0) | 5 (1) | n.s. |

| Sotalol, n (%) | 58 (6) | 14 (3) | 44 (8) | n.s. |

| Amiodarone, n (%) | 196 (19) | 95 (22) | 101 (17) | n.s. |

ASA, acetyl salicyl acid; ACE inhibitor, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor.

| Variables . | Patients on digoxin . | Patients on digitoxin . | Missing values, n (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number, n (%) | 105 (24) | 306 (70) | 27 (6) |

| Dose mean (mg) (min–max) | 0.2 (0.05–0.2) | 0.07 (0.035–0.1) | 42 (10) |

| Serum concentration median (μg/L) | 0.8 | 21.6 | 218 (50) |

| Variables . | Patients on digoxin . | Patients on digitoxin . | Missing values, n (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number, n (%) | 105 (24) | 306 (70) | 27 (6) |

| Dose mean (mg) (min–max) | 0.2 (0.05–0.2) | 0.07 (0.035–0.1) | 42 (10) |

| Serum concentration median (μg/L) | 0.8 | 21.6 | 218 (50) |

| Variables . | Patients on digoxin . | Patients on digitoxin . | Missing values, n (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number, n (%) | 105 (24) | 306 (70) | 27 (6) |

| Dose mean (mg) (min–max) | 0.2 (0.05–0.2) | 0.07 (0.035–0.1) | 42 (10) |

| Serum concentration median (μg/L) | 0.8 | 21.6 | 218 (50) |

| Variables . | Patients on digoxin . | Patients on digitoxin . | Missing values, n (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number, n (%) | 105 (24) | 306 (70) | 27 (6) |

| Dose mean (mg) (min–max) | 0.2 (0.05–0.2) | 0.07 (0.035–0.1) | 42 (10) |

| Serum concentration median (μg/L) | 0.8 | 21.6 | 218 (50) |

| Variables . | Hazard ratio . | 95% confidence interval . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Digitalis | 1.65 | 1.14–2.39 | 0.01 |

| Male gender | 2.01 | 1.21–3.33 | 0.01 |

| Age (per year) | 1.04 | 1.01–1.06 | <0.001 |

| NYHA classification | 2.02 | 1.61–2.53 | <0.001 |

| QRS duration ≥120 ms | 1.50 | 1.02–2.23 | 0.04 |

| Variables . | Hazard ratio . | 95% confidence interval . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Digitalis | 1.65 | 1.14–2.39 | 0.01 |

| Male gender | 2.01 | 1.21–3.33 | 0.01 |

| Age (per year) | 1.04 | 1.01–1.06 | <0.001 |

| NYHA classification | 2.02 | 1.61–2.53 | <0.001 |

| QRS duration ≥120 ms | 1.50 | 1.02–2.23 | 0.04 |

NYHA, New York Heart Association; CRT-D, cardiac resynchronization therapy-defibrillator.

| Variables . | Hazard ratio . | 95% confidence interval . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Digitalis | 1.65 | 1.14–2.39 | 0.01 |

| Male gender | 2.01 | 1.21–3.33 | 0.01 |

| Age (per year) | 1.04 | 1.01–1.06 | <0.001 |

| NYHA classification | 2.02 | 1.61–2.53 | <0.001 |

| QRS duration ≥120 ms | 1.50 | 1.02–2.23 | 0.04 |

| Variables . | Hazard ratio . | 95% confidence interval . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Digitalis | 1.65 | 1.14–2.39 | 0.01 |

| Male gender | 2.01 | 1.21–3.33 | 0.01 |

| Age (per year) | 1.04 | 1.01–1.06 | <0.001 |

| NYHA classification | 2.02 | 1.61–2.53 | <0.001 |

| QRS duration ≥120 ms | 1.50 | 1.02–2.23 | 0.04 |

NYHA, New York Heart Association; CRT-D, cardiac resynchronization therapy-defibrillator.

| Variables . | Patients on digitalis (n = 438) . | Patients not on digitalis (n = 582) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac arrhythmic death, n (%) | 44 (37) | 27 (32) | 0.044 |

| Cardiac non-arrhythmic death, n (%) | 32 (24) | 16 (19) | 0.036 |

| Non-cardiovascular death, n (%) | 15 (11) | 10 (12) | n.s. |

| Unknown, n (%) | 37 (28) | 32 (37) | n.s. |

| Variables . | Patients on digitalis (n = 438) . | Patients not on digitalis (n = 582) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac arrhythmic death, n (%) | 44 (37) | 27 (32) | 0.044 |

| Cardiac non-arrhythmic death, n (%) | 32 (24) | 16 (19) | 0.036 |

| Non-cardiovascular death, n (%) | 15 (11) | 10 (12) | n.s. |

| Unknown, n (%) | 37 (28) | 32 (37) | n.s. |

aCause-specific mortality classified according to Hinkle and Thaler.14

| Variables . | Patients on digitalis (n = 438) . | Patients not on digitalis (n = 582) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac arrhythmic death, n (%) | 44 (37) | 27 (32) | 0.044 |

| Cardiac non-arrhythmic death, n (%) | 32 (24) | 16 (19) | 0.036 |

| Non-cardiovascular death, n (%) | 15 (11) | 10 (12) | n.s. |

| Unknown, n (%) | 37 (28) | 32 (37) | n.s. |

| Variables . | Patients on digitalis (n = 438) . | Patients not on digitalis (n = 582) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac arrhythmic death, n (%) | 44 (37) | 27 (32) | 0.044 |

| Cardiac non-arrhythmic death, n (%) | 32 (24) | 16 (19) | 0.036 |

| Non-cardiovascular death, n (%) | 15 (11) | 10 (12) | n.s. |

| Unknown, n (%) | 37 (28) | 32 (37) | n.s. |

aCause-specific mortality classified according to Hinkle and Thaler.14

Crude Kaplan–Meier analysis of all-cause mortality in relationship to the use of digitalis.

Adjusted Kaplan–Meier analysis of all-cause mortality in relationship to the use of digitalis.

Kaplan–Meier analysis for all-cause mortality in relationship to the digitalis preparation used.

References

Author notes

J.W.E. and M.V. are first authors.

All authors take responsibility for all aspects of the reliability and freedom from bias of the data presented and their discussed interpretation.