-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Somil Verma, Chirag Agrawal, Puneet Gupta, Anunay Gupta, Accidental cannulation of amoebic liver abscess during pericardiocentesis: a case report, European Heart Journal - Case Reports, Volume 8, Issue 9, September 2024, ytae482, https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjcr/ytae482

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Amoebiasis is a prevalent infection in the tropics and can sometimes present as liver abscess. Cardiac tamponade is an uncommon complication of ruptured amoebic liver abscess requiring urgent pericardiocentesis, which has a high success rate, but procedural complications can include injury to cardiac chambers, abdominal viscera, and even death. This case underscores the approach to diagnose and manage an unintended visceral puncture during pericardiocentesis, which is a rare but life-threatening complication.

A 41-year-old male presented with intermittent fever over 2 months and chest pain for 15 days. Echocardiography revealed a significant pericardial effusion causing cardiac tamponade. In an emergency setting, percutaneous pericardiocentesis was attempted to drain the effusion. However, the pigtail inadvertently punctured a sizable liver abscess. Consequently, another pigtail was inserted into the pericardial cavity to successfully drain the effusion. Patient was discharged on Day 12 and is doing well at 6 months follow-up.

A previously undiagnosed case of a ruptured amoebic liver abscess presented with the uncommon complication of cardiac tamponade, necessitating emergency pericardiocentesis, which inadvertently led to the cannulation of the liver abscess. This case underscores the significance of image-guided pericardiocentesis in minimizing procedural complications. This case also highlights the intricacies of addressing accidental visceral puncture during pericardiocentesis, specially involving the liver. It also underscores the need to consider the possibility of a ruptured amoebic liver abscess when anchovy sauce-like pus is drained from pericardial cavity, especially in high epidemiologically prevalent country like India.

This case underscores the importance of imaging-guided pericardiocentesis.

Drainage of anchovy sauce-like pus from the pericardial cavity should alert the operator of the possibility of ruptured amoebic liver abscess especially, in a highly epidemiologically prevalent country like India.

This case also highlights how to navigate accidental visceral puncture involving the liver during pericardiocentesis, which is a rare but potentially life-threatening complication.

Introduction

Amoebiasis is a common infection, particularly prevalent in tropical regions. It manifests with a spectrum of symptoms, with bloody diarrhoea and fever being the most common. One of the most frequent extraintestinal manifestations is the development of an amoebic liver abscess, which might rupture into the pericardium, resulting in pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade, which is associated with high mortality rates.1,2 Urgent pericardiocentesis becomes imperative for tamponade management, ideally performed at the bedside with echo guidance if a cardiac catheterization laboratory is unavailable. Herein, we present a case of undetected ruptured amoebic liver abscess that presented with the rare complication of cardiac tamponade requiring urgent pericardiocentesis, which resulted in accidental cannulation of the liver abscess, necessitating subsequent pigtail drainage for tamponade management.

Summary figure

Case presentation

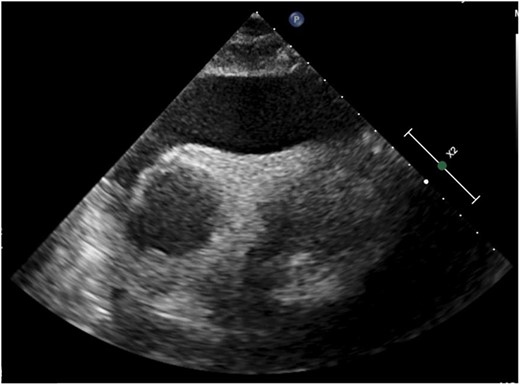

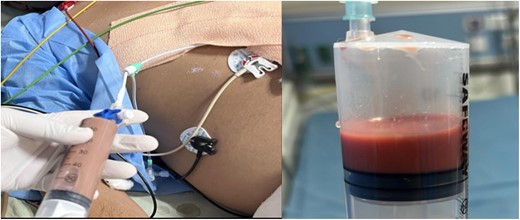

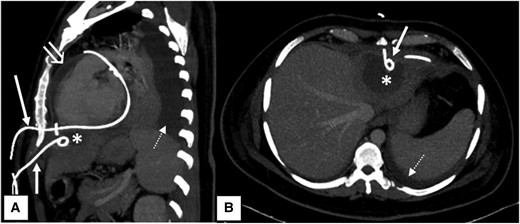

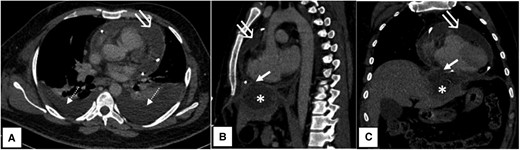

A 41-year-old man with no previous comorbidities presented to the cardiology department with a history of intermittent fever for 2 months and chest pain for 15 days. He had received empirical antibiotics and anti-pyrectics without any symptomatic relief. There was no history of similar complaints in the past, and the family history was non-contributory. On examination, the patient was well built, with a body mass index of 23.4 kg/m2. He was febrile with a blood pressure of 90/62 mmHg, a pulse rate of 112/min, and a respiratory rate of 24/min, with muffled heart sounds and jugular venous distension. The electrocardiogram was suggestive of pericarditis with generalized up-coving ST-segment elevation and PR segment depression (Supplementary material online, Figure S1). A transthoracic 2D echocardiogram revealed a large pericardial effusion with diastolic collapse of the right ventricle, suggestive of cardiac tamponade (Figure 1, Supplementary material online, Video S1). Emergency subxiphoid percutaneous pericardiocentesis was attempted under 2D echocardiography guidance, and 50 mL of anchovy sauce-like pus was aspirated (Figure 2) and a 5F pigtail catheter was inserted. Since there was aspiration of frank pus, agitated saline was not used to confirm the position of the needle. However, when the pigtail position was confirmed under fluoroscopy, it was below the diaphragm (Supplementary material online, Figure S2). The possibility of a liver abscess was considered, with accidental needle puncture and pigtail insertion in the abscess cavity. Pericardiocentesis was reattempted under fluoroscopy, and after confirming the needle position with agitated saline, another pigtail was placed in the pericardium and 350 mL of pus was drained. Results and reference values, according to age and sex, of the most relevant laboratory tests performed on our patient at presentation are tabulated in Table 1. Ultrasonography of the abdomen confirmed that the first pigtail was present in the left lobe liver abscess with a 50–60 mL residual abscess that was non-aspirable. A chest X-ray done post-pericardiocentesis showed cardiomegaly with two pigtails in situ, one each in the pericardium and liver, respectively. Intervention radiology, surgery, and gastroenterology opinions were sought regarding the management of the liver abscess, and it was decided to continue conservative management since the accidental liver cannulation was in the abscess cavity only and the patient was haemodynamically stable. Although no amoeba was cultivated from the pus, the polymerase chain reaction from the pus was positive for Entamoeba histolytica. Therefore, the patient was started on intravenous metronidazole 800 mg thrice daily. Repeat echocardiography revealed mild pericardial effusion with 11–12 mm pericardial separation lateral and posterior to the left ventricle. The pigtail was repositioned, and 50–60 mL of pus was aspirated. Non-contrast computed tomography of chest and abdomen (Figures 3 and 4) revealed pericardial effusion with a maximum pericardial separation of 10 mm with a pigtail in situ with bilateral pleural effusion and a collapsed underlying lung along with hepatomegaly with a liver span of 18.7 cm and 5.5 × 5.5 × 4 cm of well-defined peripherally enhancing heterogeneously hypodense collection with a central core of thick fluid attenuation likely suggestive of an abscess in Segment 2 of the left liver lobe with extension into the subphrenic space communicating with the overlying pericardial cavity through an 8 mm rent. A pigtail tip was also seen in situ in the liver abscess. A repeat ultrasonography of abdomen was done on Day 7, which revealed a 65 mL liver abscess with aspirable content. Since the pus could not be drained using a 5F pigtail, the pigtail was exchanged with a 6F pigtail, and 30 mL of pus was aspirated. The pericardial pigtail was removed on Day 9 after there was no aspirate for 3 consecutive days. Repeat abdominal ultrasonography revealed no residual abscess in the liver, so the liver pigtail was removed on Day 11. The patient was discharged on Day 14 and is doing well at 1 and 6 months follow-up. There was no evidence of constrictive physiology on follow-up 2D echocardiography.

2D echocardiogram (subcostal view) demonstrating massive pericardial effusion.

Computed tomography scan. Sagittal (A) and axial (B) maximum intensity projection contrast-enhanced computed tomography images of the patient showing two pigtail drainage catheters in situ inserted by subcoastal approach. The upper one (long white arrow) was inserted left lateral to xiphisternum and directly entering into the pericardial cavity. The lower one (short white arrow) was inserted below the level of xiphisternum and draining the hypodense hepatic abscess (asterisk) in segment II of left lobe of liver. Note made of associated pericardial collection with enhancing parietal pericardial lining (open white arrow) and left-sided pleural effusion (dashed white arrow).

Axial (A), sagittal (B), and coronal (C) contrast-enhanced computed tomography images showing a hypodense pericardial collection with an enhancing parietal pericardial lining (open white arrow) and bilateral pleural effusion (dashed white arrow) with underlying basal lung collapse. Peripherally enhancing hypodense subcapsular hepatic abscess (asterisk) in left lobe segment II, rupturing into the pericardial cavity via a small defect (short white arrow) through the diaphragm.

| Laboratory examination . | Results . | Reference value . |

|---|---|---|

| Haemoglobin | 8.1 | 13.5–17.5 g/dL |

| Creatinine | 1.81 | 0.7–1.2 mg/dL |

| Total leucocyte count | 32 200 | 4000–11 000/μL |

| Total bilirubin | 1.2 | 0.0–1.4 mg/dL |

| Conjugated bilirubin | 0.7 | 0.0–0.3 mg/dL |

| SGOT | 32 | 5–40 U/L |

| SGPT | 34 | 7–56 U/L |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 141 | 20–140 U/L |

| HIV 1 and 2 | Non-reactive | – |

| HBsAg | Non-reactive | – |

| Anti-HCV | Non-reactive | – |

| PCT | 1.7 | 0.5 ng/mL |

| C-reactive protein | 24 | 0–6.0 mg/L |

| Laboratory examination . | Results . | Reference value . |

|---|---|---|

| Haemoglobin | 8.1 | 13.5–17.5 g/dL |

| Creatinine | 1.81 | 0.7–1.2 mg/dL |

| Total leucocyte count | 32 200 | 4000–11 000/μL |

| Total bilirubin | 1.2 | 0.0–1.4 mg/dL |

| Conjugated bilirubin | 0.7 | 0.0–0.3 mg/dL |

| SGOT | 32 | 5–40 U/L |

| SGPT | 34 | 7–56 U/L |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 141 | 20–140 U/L |

| HIV 1 and 2 | Non-reactive | – |

| HBsAg | Non-reactive | – |

| Anti-HCV | Non-reactive | – |

| PCT | 1.7 | 0.5 ng/mL |

| C-reactive protein | 24 | 0–6.0 mg/L |

Anti-HCV, antibody to the hepatitis C virus; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PCT, procalcitonin; SGOT, serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase; SGPT, serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase.

| Laboratory examination . | Results . | Reference value . |

|---|---|---|

| Haemoglobin | 8.1 | 13.5–17.5 g/dL |

| Creatinine | 1.81 | 0.7–1.2 mg/dL |

| Total leucocyte count | 32 200 | 4000–11 000/μL |

| Total bilirubin | 1.2 | 0.0–1.4 mg/dL |

| Conjugated bilirubin | 0.7 | 0.0–0.3 mg/dL |

| SGOT | 32 | 5–40 U/L |

| SGPT | 34 | 7–56 U/L |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 141 | 20–140 U/L |

| HIV 1 and 2 | Non-reactive | – |

| HBsAg | Non-reactive | – |

| Anti-HCV | Non-reactive | – |

| PCT | 1.7 | 0.5 ng/mL |

| C-reactive protein | 24 | 0–6.0 mg/L |

| Laboratory examination . | Results . | Reference value . |

|---|---|---|

| Haemoglobin | 8.1 | 13.5–17.5 g/dL |

| Creatinine | 1.81 | 0.7–1.2 mg/dL |

| Total leucocyte count | 32 200 | 4000–11 000/μL |

| Total bilirubin | 1.2 | 0.0–1.4 mg/dL |

| Conjugated bilirubin | 0.7 | 0.0–0.3 mg/dL |

| SGOT | 32 | 5–40 U/L |

| SGPT | 34 | 7–56 U/L |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 141 | 20–140 U/L |

| HIV 1 and 2 | Non-reactive | – |

| HBsAg | Non-reactive | – |

| Anti-HCV | Non-reactive | – |

| PCT | 1.7 | 0.5 ng/mL |

| C-reactive protein | 24 | 0–6.0 mg/L |

Anti-HCV, antibody to the hepatitis C virus; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PCT, procalcitonin; SGOT, serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase; SGPT, serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase.

Discussion

Amoebiasis is a widespread infection worldwide, affecting around 12% of the global population, with mortality rates ranging between 1 and 3%.3 If it spreads through the bloodstream, then it can lead to liver abscesses, which primarily affect adult men, predominantly in the right lobes, with single abscesses being more common. Cases involving the left lobe are associated with a higher incidence of extraintestinal involvement.4 Medical management with metronidazole remains the cornerstone of therapy, significantly reducing mortality and morbidity. The standard metronidazole dosage is 750 mg thrice daily for 7–10 days. Intraluminal agents like paromomycin and diloxanide furoate are added to prevent relapse.5

In cases where a high risk of rupture exists, therapeutic aspiration through image-guided percutaneous interventions, such as needle aspiration or pigtail catheters, is recommended.6 Pericardiocentesis is a life-saving measure for managing large, symptomatic pericardial effusions and cardiac tamponade. Echocardiography-guided pericardiocentesis has a high success rate of over 95% with minimal risk. Complications, though varied, can include injury to cardiac chambers, laceration of coronary arteries or intercostal vessels, ventricular arrhythmia, pericardial decompression syndrome, and even death.7 Pneumopericardium has also been reported in the literature as a potential complication.8

Various approaches, such as parasternal, apical, and subxiphoid, are well documented for pericardiocentesis. The subxiphoid route, chosen in this case, is associated with fewer complications. Risks related to this approach include intraprocedural injury to the diaphragm, phrenic nerve, inferior vena cava, hepatic vessels, liver, colon, and stomach. Rare instances of accidental cannulation of the cardiac venous system have also been reported.9 In our case, pericardiocentesis was performed in an undiagnosed cardiac tamponade case via the subxiphoid approach in an emergency under 2D echocardiography guidance, as subxiphoid approach is associated with fewer complications. During the procedure, the needle inadvertently entered the liver, leading to the incidental discovery of a liver abscess that had ruptured into the pericardium, causing pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade. Subsequently, another pigtail was inserted into the pericardium to drain the pericardial effusion.

Although the risk of abdominal visceral puncture is acknowledged, reported cases of liver puncture due to pericardiocentesis are infrequent and necessitate an emergency laparotomy for haemostasis.10 Similar cases have been reported before, too. In one such instance, liver rupture and diaphragmatic perforation occurred during pericardiocentesis, which resulted in pneumohaemoperitoneum. The patient required surgical intervention to remove the drain safely.11

Such procedural complications can be avoided by doing every step carefully and meticulously. The subxiphoid approach should be preferred, and punctures should be taken under fluoroscopy guidance to prevent an abnormal course of the puncture needle. The position of the needle should be confirmed by injecting a small amount of dye into the pericardial space, and following that, the sheath should be inserted. If the procedure is attempted under 2D echocardiography guidance, then agitated saline can be used to confirm the position of the sheath in the pericardial space.

Conclusion

To conclude, our case presents a rare manifestation of an amoebic liver abscess rupturing into the pericardial space and causing cardiac tamponade. While draining pericardial effusion, aspiration of anchovy sauce-like pus should alert the physician to the possibility of a ruptured amoebic liver abscess as a possible aetiology. It also underscores the importance of image-guided pericardiocentesis along with additional methods to ensure that the puncture needle is in the pericardium to avoid procedure-related complications, including abdominal viscera puncture.

Lead author biography

Somil Verma is an undergraduate from Grant Medical College, Mumbai, and a postgraduate from Dr SN Medical College Jodhpur. He is currently doing his DM in cardiology as a senior resident in VMMC and Safdarjung Hospital, New Delhi. His areas of interests are coronary and structural interventions, 2D echocardiography, and teaching.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal – Case Reports online.

Consent: The authors confirm that written consent for submission and publication of this case report including image(s) and associated text has been obtained from the patient in line with COPE guidance.

Acknowledgements

We extend our heartfelt thanks to Dr. M. Sarthak Swarup, Assistant Professor of Radiodiagnosis at VMMC and Safdarjung Hospital, for his crucial support in this study. Dr. Swarup's expert assistance in labeling and providing the CT images was instrumental to our research. His dedication and expertise significantly contributed to the quality and depth of our analysis.

Funding: None declared.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary material. Raw data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

References

Author notes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Comments