-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Andreas Bugge Tinggaard, Kasper Korsholm, Jesper Møller Jensen, Jens Erik Nielsen-Kudsk, Spontaneously occluded left atrial appendage in a patient with atrial fibrillation and stroke: a case report, European Heart Journal - Case Reports, Volume 4, Issue 2, June 2020, Pages 1–4, https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjcr/ytaa027

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The left atrial appendage (LAA) is the main source of thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation (AF). Transcatheter closure is non-inferior to warfarin therapy in preventing stroke.

A patient with two consecutive strokes associated with AF was referred for transcatheter LAA occlusion (LAAO). Preprocedural cardiac CT and transoesophageal echocardiography demonstrated a spontaneously occluded LAA with a smooth left atrial surface, with stationary results at 6- and 12-month imaging follow-up. Warfarin was discontinued, and life-long aspirin instigated.

Left atrial appendage occlusion has shown non-inferiority to warfarin for prevention of stroke, cardiovascular death, and all-cause mortality. No benefits from anticoagulation have been demonstrated in patients with embolic stroke of undetermined source. In the present case, we observed that the LAA was occluded and, therefore, treated with aspirin monotherapy assuming similar efficacy as transcatheter LAAO.

Left atrial appendage occlusion is a valuable alternative to anticoagulants for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation.

Anticoagulants have shown no beneficial effects in patients with stroke of undetermined source.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is associated with a three- to five-fold increased risk of stroke,1 and the left atrial appendage (LAA) is known to be the source of thrombi in patients AF. Transcatheter LAA occlusion (LAAO) has shown non-inferiority to warfarin.2

Approximately 25% of ischaemic strokes are not associated with recognized cardioembolic sources or carotid atherosclerosis,3 thus, categorized as embolic stroke of undetermined source (ESUS). Anticoagulation therapy has demonstrated no beneficial effects in patients with ESUS.4

Few cases of absent LAA have previously been described.5–9 This case illustrates a spontaneously occluded LAA in a patient with AF and thromboembolic stroke.

Timeline

| Index date | First admission with stroke, patient discharged with dabigatran. |

| 17 days | Second admission, transient ischaemic attack. Patient changed to warfarin treatment and referred for left atrial appendage (LAA) occlusion. |

| 5 months | Cardiac CT and 3D-transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE) show signs of chronic thrombotic occlusion of the LAA. |

| 11 months | Repeated CT and TOE show stationary results. |

| 1 year and 6 months | Third CT and TOE again show stationary results. Warfarin was discontinued and life-long aspirin was initiated. |

| Index date | First admission with stroke, patient discharged with dabigatran. |

| 17 days | Second admission, transient ischaemic attack. Patient changed to warfarin treatment and referred for left atrial appendage (LAA) occlusion. |

| 5 months | Cardiac CT and 3D-transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE) show signs of chronic thrombotic occlusion of the LAA. |

| 11 months | Repeated CT and TOE show stationary results. |

| 1 year and 6 months | Third CT and TOE again show stationary results. Warfarin was discontinued and life-long aspirin was initiated. |

| Index date | First admission with stroke, patient discharged with dabigatran. |

| 17 days | Second admission, transient ischaemic attack. Patient changed to warfarin treatment and referred for left atrial appendage (LAA) occlusion. |

| 5 months | Cardiac CT and 3D-transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE) show signs of chronic thrombotic occlusion of the LAA. |

| 11 months | Repeated CT and TOE show stationary results. |

| 1 year and 6 months | Third CT and TOE again show stationary results. Warfarin was discontinued and life-long aspirin was initiated. |

| Index date | First admission with stroke, patient discharged with dabigatran. |

| 17 days | Second admission, transient ischaemic attack. Patient changed to warfarin treatment and referred for left atrial appendage (LAA) occlusion. |

| 5 months | Cardiac CT and 3D-transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE) show signs of chronic thrombotic occlusion of the LAA. |

| 11 months | Repeated CT and TOE show stationary results. |

| 1 year and 6 months | Third CT and TOE again show stationary results. Warfarin was discontinued and life-long aspirin was initiated. |

Case presentation

A 57-year-old man with a history of well-treated hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, and prior smoking was hospitalized with symptoms of ischaemic stroke: facial palsy, left-sided neglect, and dysarthria. Complete occlusion of the right internal carotid artery was found by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The patient was treated with intra-arterial thrombectomy and thrombolysis. No extra- or intracranial arteriosclerosis or signs of intracerebral small vessel disease was present on MRI. Electrocardiogram showed atrial fibrillation (AF) and echocardiography a structurally normal heart. All laboratory tests were within normal range. The CHA2DS2-VASc score was 3, and the patient was discharged for elective cardioversion with dabigatran 150 mg twice daily.

Symptoms of a transient ischaemic attack (TIA) lead to re-hospitalization 17 days later with MRI showing a fresh ischaemic lesion in the right insular cortex. Electrocardiogram showed (persistent) AF. A transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE) excluded intracardiac thrombi and patent foramen ovale. However, the LAA could not be visualized. Dabigatran was substituted with warfarin and the patient was referred for transcatheter LAAO.

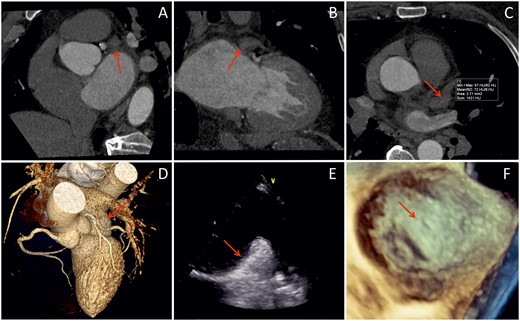

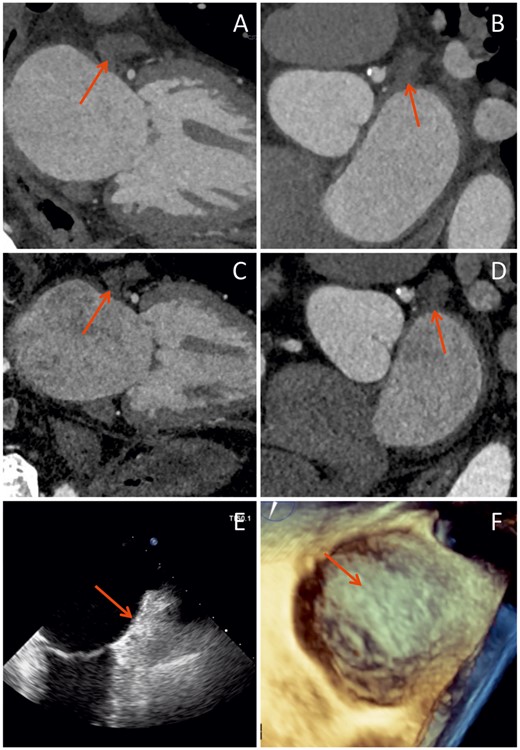

A cardiac computed tomography (CT) was performed as preprocedural evaluation for LAAO. Despite optimal acquisition, there was no contrast filling of the LAA. However, the multiplanar reconstructed images revealed the contours of an LAA, with the orifice covered by a smooth surface in continuation of the left atrial wall (Figure 1). A three-dimensional TOE confirmed absence of the LAA with a smooth-walled surface covering the orifice. Based on a multidisciplinary team conference, warfarin therapy was continued. Cardiac CT and TOE were repeated after 6 and 12 months, respectively, with stationary results (Figure 2). After the 12-month scan, warfarin was discontinued, and life-long aspirin, 75 mg daily, was initiated. During treatment with aspirin for 24 months there has been no recurrent stroke or TIA.

Baseline imaging showing no left atrial appendage (arrows). (A–C) Computed tomography scans, (D) three-dimensional computed tomography rendering, (E) transoesophageal echocardiography, and (F) three-dimensional transoesophageal echocardiography.

A follow-up imaging showing stationary results. (A and B) Six-month computed tomography scan, (C and D) 12-month computed tomography scan, (E) 12-month transoesophageal echocardiography, and (F) 12-month three-dimensional transoesophageal echocardiography.

Discussion

Absence of the LAA is a rare cardiac anomaly, with a presumed congenital aetiology.5–9 In contrast to previous reports, we found signs of a remnant LAA defined by the presence of hypo-attenuation and demarcation of the LAA on cardiac CT. These findings could suggest that absence of the LAA, in this case, was caused by chronic thrombotic occlusion. Histological confirmation would have been ideal, but implicitly was not possible. Other imaging modalities, e.g. cardiac MRI, might have provided additional information, however, given the higher spatial resolution of cardiac CT the additional value is uncertain.10 In addition, thrombophilia screening could have been applied; however, the usefulness of this in stroke patients is unknown, thus, routine testing is not recommended in guidelines.11 A large study (n = 685) found no association between thrombophilia and stroke, as most prothrombotic conditions increase the risk of venous thrombosis.12

The LAA has been identified as the origin of thromboembolism in AF.13 A recent TOE study of consecutive patients prior to cardioversion of AF or atrial flutter showed thrombosis outside the LAA to be extremely rare, and only present with a simultaneous LAA thrombus.14 Left atrial appendage occlusion has demonstrated similar or even higher efficacy than warfarin for prevention of ischaemic stroke, cardiovascular death, and all-cause mortality with a concomitant reduction in the rate of major bleedings.2,15 Patients undergoing transcatheter LAAO are often treated life-long aspirin therapy. This resembles the secondary preventive strategy of stroke in the absence of AF. In this particular patient, we considered the LAA to be chronically occluded, thereby the source of cardiac embolism in relation to his AF was eliminated. In the absence of lacunar stroke, extra- or intracranial atherosclerosis causing ≥50% luminal stenosis, and no patent foramen ovale or LAA, we considered the patient to fulfil the criteria of an embolic stroke with undetermined source.3 The NAVIGATE-ESUS and RESPECT-ESUS trials demonstrated no additional value of rivaroxaban or dabigatran to prevent recurrent stroke as compared to ASA monotherapy.4,16 However, the risk of major bleeding was significantly higher with rivaroxaban in NAVIGATE-ESUS and the risk of non-major bleeding was higher with dabigatran in RESPECT-ESUS. Due to a history of intracranial haemorrhage in a closely related family member, the patient was reluctant to anticoagulation therapy. To our knowledge, only one previous case report has addressed the decision of anticoagulation treatment in a patient with (congenital) absent LAA and atrial fibrillation.17 In that case, the patient had a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 4 and the anticoagulation treatment was continued. This patient had a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 3, and HAS-BLED score of 1. Considering the unconvincing benefits of anticoagulation therapy in this particular patient, we chose to treat the patient with ASA monotherapy assuming that the spontaneously occluded LAA would prevent thromboembolic complications similar to a transcatheter LAAO and in order to keep the bleeding risk low.18

Lead author biography

Andreas Bugge Tinggaard is a junior doctor at the Department of Cardiology, Aarhus University Hospital, Denmark. His field of interest includes atrial fibrillation, anticoagulation therapy, left atrial appendage occlusion, and stroke prevention.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal - Case Reports online.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to give an honourable mention to Professor Grethe Andersen, DMSc, from Department of Neurology, Aarhus University Hospital, for her contribution to this case.

Slide sets: A fully edited slide set detailing this case and suitable for local presentation is available online as Supplementary data.

Consent: A verbal consent has been obtained from the patient prior to any work up regarding this article and prior to submission. By Danish law, this is required to access any of the patient’s data in the electronic medical record and to use it for scientific and educational purposes. The consent has been documented in the electronic medical record.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Comments