-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Raphael P Martins, Mathilde Hamel-Bougault, Francis Bessière, Matteo Pozzi, Fabrice Extramiana, Zohra Brouk, Charles Guenancia, Audrey Sagnard, Sandro Ninni, Céline Goemine, Pascal Defaye, Aude Boignard, Baptiste Maille, Vlad Gariboldi, Pierre Baudinaud, Anne-Céline Martin, Laure Champ-Rigot, Katrien Blanchart, Jean-Marc Sellal, Christian De Chillou, Katia Dyrda, Laurence Jesel-Morel, Michel Kindo, Corentin Chaumont, Frédéric Anselme, Clément Delmas, Philippe Maury, Marine Arnaud, Erwan Flecher, Karim Benali, Heart transplantation as a rescue strategy for patients with refractory electrical storm, European Heart Journal. Acute Cardiovascular Care, Volume 12, Issue 9, September 2023, Pages 571–581, https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjacc/zuad063

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Heart transplantation (HT) can be proposed as a therapeutic strategy for patients with severe refractory electrical storm (ES). Data in the literature are scarce and based on case reports. We aimed at determining the characteristics and survival of patients transplanted for refractory ES.

Patients registered on HT waiting list during the following days after ES and eventually transplanted, from 2010 to 2021, were retrospectively included in 11 French centres. The primary endpoint was in-hospital mortality. Forty-five patients were included [82% men; 55.0 (47.8–59.3) years old; 42.2% and 26.7% non-ischaemic dilated or ischaemic cardiomyopathies, respectively]. Among them, 42 (93.3%) received amiodarone, 29 received (64.4%) beta blockers, 19 (42.2%) required deep sedation, 22 had (48.9%) mechanical circulatory support, and 9 (20.0%) had radiofrequency catheter ablation. Twenty-two patients (62%) were in cardiogenic shock. Inscription on wait list and transplantation occurred 3.0 (1.0–5.0) days and 9.0 (4.0–14.0) days after ES onset, respectively. After transplantation, 20 patients (44.4%) needed immediate haemodynamic support by extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). In-hospital mortality rate was 28.9%. Predictors of in-hospital mortality were serum creatinine/urea levels, need for immediate post-operative ECMO support, post-operative complications, and surgical re-interventions. One-year survival was 68.9%.

Electrical storm is a rare indication of HT but may be lifesaving in those patients presenting intractable arrhythmias despite usual care. Most patients can be safely discharged from hospital, although post-operative mortality remains substantial in this context of emergency transplantation. Larger studies are warranted to precisely determine those patients at higher risk of in-hospital mortality.

Introduction

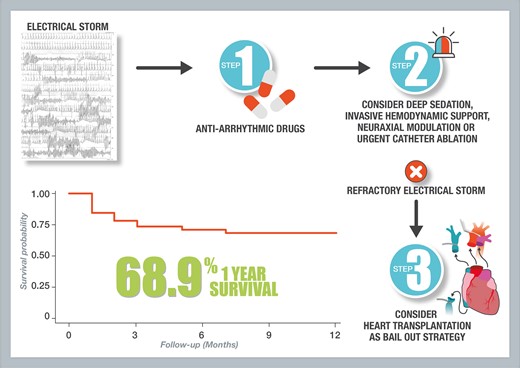

Electrical storm (ES) is a life-threatening condition, characterized by the occurrence of recurrent episodes of ventricular arrhythmias in a short period of time.1–4 The usual management of ES consists, on one hand, in treating potential triggers and, on the other hand, in administering anti-arrhythmic drugs and/or perform catheter ablation.5–8 In some cases of major electrical instability, deep sedation associated with mechanical ventilatory support, invasive haemodynamic support, or neuraxial modulation may help to restore a stable sinus rhythm.

In rare cases, heart transplantation (HT) is performed as a rescue treatment for refractory ES. Data regarding this specific indication of emergency HT in literature are scarce, limited to case reports.9–11

The aim of this multicentre study was to determine patient characteristics and factors associated with short-term mortality in the context of emergency HT for refractory ES.

Methods

Study population

This study is a retrospective multicentre observational study of patients undergoing HT due to refractory ES in 11 French centres from 2010 to 2021. Inclusion criteria were patients registered on HT waiting list during the 7 days following ES or patients already registered before ES due to their underlying cardiomyopathy, but switched to super-urgent list during the following 7 days after an ES. Exclusion criteria were adults under legal protection or aged <18 years old. This study was approved by the local ethic committee. Patients gave their informed consent to participate in the study.

Ventricular arrhythmias and electrical storm

Electrical storm was consensually defined as the occurrence of at least three or more distinct episodes of sustained ventricular arrhythmias within 24 h or incessant ventricular arrhythmias for more than 12 h.1,2 In patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD), ES was defined by the occurrence of more than three appropriate device therapies within 24 h, separated by at least 5 min.1,2,12

Baseline assessment and follow-up

Baseline data, including demographic characteristics, type of cardiomyopathy, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), history of ventricular arrhythmias prior to ES, ICD implantation, and usual treatment, were collected from medical files for all enrolled patients. In-hospital data were collected including ES treatment, clinical presentation, LVEF and laboratory parameters before HT, complications after surgery and the occurrence of in-hospital death, and hospital discharge date. Primary graft dysfunction was defined according to the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation 2014 consensus.13 Follow-up was performed after hospital discharge according to local hospital protocol.

Study endpoints

The primary endpoint was in-hospital mortality. Secondary endpoints were overall survival at 1 and 5 years after HT.

Statistical analysis

Qualitative variables were expressed as number (percentage). Normally distributed variables were expressed as means ± standard deviation and compared using Student’s t-test. Non-normally distributed variables were expressed as median and interquartile ranges and compared using Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical variables were expressed as counts and percentages and were compared using the Chi-square test or exact Fisher’s exact test when needed. Time-survival estimation curves were generated using Kaplan–Meier estimates, with comparisons of cumulative event rates by using the log-rank test. Univariate Cox proportional hazard regression analyses were used to identify factors associated with the 12-month mortality after HT for ES. Results are expressed as Hazard Ratio and 95% confidence interval for each variable. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using the 4.0.0 version R.

Results

Study population

A total of 45 patients were included in the study. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Patients had a median age of 55.0 (47.8–59.3) years old and 37 (82.2%) were male. The underlying heart disease was a non-ischaemic dilated cardiomyopathy for 19 (42.2%) patients and an ischaemic cardiomyopathy for 12 (26.7%) patients. The remaining patients had congenital, arrhythmogenic right ventricular, hypertrophic or lamin A/C mutation cardiomyopathies. The median LVEF was 25.0% (20.0–34.3). Forty-one patients (91.1%) had an ICD, half of them implanted as secondary prevention. Thirty-two patients (71.1%) had a history of ventricular arrhythmia, and 12 (26.7%) had a previous history of ES. Regarding the medication before ES onset, 40 patients (88.9%) were treated with beta blockers, and 22 (48.9%) with amiodarone. Three patients (6.7%) had a left ventricular assist device (LVAD) previously implanted. The ES leading to HT happened a median time of 11.0 (5.0–16.5) years after the diagnosis of the underlying cardiomyopathy.

| . | All patients (n = 45) . | Patients alive at hospital discharge (n = 32) . | Patients died during hospitalization (n = 13) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 55.0 (47.8–59.3) | 53.5 (47.5–59.0) | 58.0 (50.0–63.5) | 0.259 |

| Male gender | 37 (82.2) | 26 (81.2) | 11 (84.6) | 1.000 |

| Body mass index, kg/m² | 26.6 ± 4.1 | 26.2 ± 3.9 | 27.7 ± 4.5 | 0.248 |

| Hypertension | 17 (37.8) | 12 (37.5) | 5 (38.5) | 1.000 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 6 (13.3) | 3 (9.4) | 3 (23.1) | 0.334 |

| Dyslipidemia | 10 (22.2) | 8 (25.0) | 2 (15.4) | 0.698 |

| History of smoking | 17 (37.8) | 12 (37.5) | 5 (38.5) | 1.000 |

| Heredity | 2 (4.4) | 2 (6.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| Cardiomyopathy: | ||||

| − Non-ischaemic dilated cardiomyopathy | 19 (42.2) | 14 (43.8) | 5 (38.5) | |

| − Ischaemic cardiomyopathy | 12 (26.7) | 8 (25.0) | 4 (30.8) | |

| − ARVC | 5 (11.1) | 2 (6.2) | 3 (23.1) | 0.162 |

| − Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 5 (11.1) | 5 (15.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| − Lamin A/C mutation cardiomyopathy | 3 (6.7) | 3 (9.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| − Congenital cardiomyopathy | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | |

| Implantable cardioverter defibrillator | 41 (91.1) | 31 (96.9) | 10 (76.9) | 0.066 |

| − Secondary prevention | 21 (46.7) | 17 (53.1) | 4 (30.8) | 0.302 |

| − Single chamber | 10 (22.2) | 8 (25.0) | 2 (15.4) | |

| − Dual chamber | 8 (17.8) | 5 (15.6) | 3 (23.1) | 0.302 |

| − Resynchronization therapy | 13 (28.9) | 10 (31.2) | 3 (23.1) | |

| − Subcutaneous ICD | 1 (2.2) | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| History of ventricular arrhythmia | 32 (71.1) | 24 (75.0) | 8 (61.5) | 0.473 |

| History of ES | 12 (26.7) | 8 (25.0) | 4 (30.8) | 0.721 |

| History of VT ablation | 12 (26.7) | 8 (25.0) | 4 (30.8) | 0.721 |

| LVEF, % | 25.0 (20.0–34.3) | 26.5 (24.5–34.5) | 25.0 (18.8–33.0) | 0.325 |

| LVAD | 3 (6.7) | 2 (6.3) | 1 (7.7) | 1.000 |

| Usual treatment prior to ES: | ||||

| − Beta blockers | 40 (88.9) | 29 (90.6) | 11 (84.6) | 0.617 |

| − Amiodarone | 22 (48.9) | 13 (40.6) | 9 (69.2) | 0.108 |

| − ACEI/ARB | 25 (55.6) | 18 (56.3) | 7 (53.8) | 0.854 |

| − Sacubitril/valsartan | 11 (24.4) | 10 (31.2) | 1 (7.7) | 0.136 |

| − MRA | 19 (42.2) | 16 (50.0) | 3 (23.1) | 0.182 |

| − Diuretic agents | 31 (68.9) | 21 (65.6) | 10 (76.9) | 0.724 |

| − Anticoagulant | 25 (55.6) | 19 (59.4) | 6 (46.2) | 0.515 |

| − Antiplatelet agents | 11 (24.4) | 7 (21.9) | 4 (30.8) | 0.704 |

| − Statin | 13 (28.9) | 9 (28.1) | 4 (30.8) | 1.000 |

| Time from cardiomyopathy diagnosis to ES (years) | 11.0 (5.0–16.5) | 12 (5.0–18.5) | 9 (5.8–12.5) | 0.490 |

| . | All patients (n = 45) . | Patients alive at hospital discharge (n = 32) . | Patients died during hospitalization (n = 13) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 55.0 (47.8–59.3) | 53.5 (47.5–59.0) | 58.0 (50.0–63.5) | 0.259 |

| Male gender | 37 (82.2) | 26 (81.2) | 11 (84.6) | 1.000 |

| Body mass index, kg/m² | 26.6 ± 4.1 | 26.2 ± 3.9 | 27.7 ± 4.5 | 0.248 |

| Hypertension | 17 (37.8) | 12 (37.5) | 5 (38.5) | 1.000 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 6 (13.3) | 3 (9.4) | 3 (23.1) | 0.334 |

| Dyslipidemia | 10 (22.2) | 8 (25.0) | 2 (15.4) | 0.698 |

| History of smoking | 17 (37.8) | 12 (37.5) | 5 (38.5) | 1.000 |

| Heredity | 2 (4.4) | 2 (6.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| Cardiomyopathy: | ||||

| − Non-ischaemic dilated cardiomyopathy | 19 (42.2) | 14 (43.8) | 5 (38.5) | |

| − Ischaemic cardiomyopathy | 12 (26.7) | 8 (25.0) | 4 (30.8) | |

| − ARVC | 5 (11.1) | 2 (6.2) | 3 (23.1) | 0.162 |

| − Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 5 (11.1) | 5 (15.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| − Lamin A/C mutation cardiomyopathy | 3 (6.7) | 3 (9.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| − Congenital cardiomyopathy | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | |

| Implantable cardioverter defibrillator | 41 (91.1) | 31 (96.9) | 10 (76.9) | 0.066 |

| − Secondary prevention | 21 (46.7) | 17 (53.1) | 4 (30.8) | 0.302 |

| − Single chamber | 10 (22.2) | 8 (25.0) | 2 (15.4) | |

| − Dual chamber | 8 (17.8) | 5 (15.6) | 3 (23.1) | 0.302 |

| − Resynchronization therapy | 13 (28.9) | 10 (31.2) | 3 (23.1) | |

| − Subcutaneous ICD | 1 (2.2) | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| History of ventricular arrhythmia | 32 (71.1) | 24 (75.0) | 8 (61.5) | 0.473 |

| History of ES | 12 (26.7) | 8 (25.0) | 4 (30.8) | 0.721 |

| History of VT ablation | 12 (26.7) | 8 (25.0) | 4 (30.8) | 0.721 |

| LVEF, % | 25.0 (20.0–34.3) | 26.5 (24.5–34.5) | 25.0 (18.8–33.0) | 0.325 |

| LVAD | 3 (6.7) | 2 (6.3) | 1 (7.7) | 1.000 |

| Usual treatment prior to ES: | ||||

| − Beta blockers | 40 (88.9) | 29 (90.6) | 11 (84.6) | 0.617 |

| − Amiodarone | 22 (48.9) | 13 (40.6) | 9 (69.2) | 0.108 |

| − ACEI/ARB | 25 (55.6) | 18 (56.3) | 7 (53.8) | 0.854 |

| − Sacubitril/valsartan | 11 (24.4) | 10 (31.2) | 1 (7.7) | 0.136 |

| − MRA | 19 (42.2) | 16 (50.0) | 3 (23.1) | 0.182 |

| − Diuretic agents | 31 (68.9) | 21 (65.6) | 10 (76.9) | 0.724 |

| − Anticoagulant | 25 (55.6) | 19 (59.4) | 6 (46.2) | 0.515 |

| − Antiplatelet agents | 11 (24.4) | 7 (21.9) | 4 (30.8) | 0.704 |

| − Statin | 13 (28.9) | 9 (28.1) | 4 (30.8) | 1.000 |

| Time from cardiomyopathy diagnosis to ES (years) | 11.0 (5.0–16.5) | 12 (5.0–18.5) | 9 (5.8–12.5) | 0.490 |

ACEI/ARB, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker; ARVC, arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy; ES, electrical storm; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

| . | All patients (n = 45) . | Patients alive at hospital discharge (n = 32) . | Patients died during hospitalization (n = 13) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 55.0 (47.8–59.3) | 53.5 (47.5–59.0) | 58.0 (50.0–63.5) | 0.259 |

| Male gender | 37 (82.2) | 26 (81.2) | 11 (84.6) | 1.000 |

| Body mass index, kg/m² | 26.6 ± 4.1 | 26.2 ± 3.9 | 27.7 ± 4.5 | 0.248 |

| Hypertension | 17 (37.8) | 12 (37.5) | 5 (38.5) | 1.000 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 6 (13.3) | 3 (9.4) | 3 (23.1) | 0.334 |

| Dyslipidemia | 10 (22.2) | 8 (25.0) | 2 (15.4) | 0.698 |

| History of smoking | 17 (37.8) | 12 (37.5) | 5 (38.5) | 1.000 |

| Heredity | 2 (4.4) | 2 (6.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| Cardiomyopathy: | ||||

| − Non-ischaemic dilated cardiomyopathy | 19 (42.2) | 14 (43.8) | 5 (38.5) | |

| − Ischaemic cardiomyopathy | 12 (26.7) | 8 (25.0) | 4 (30.8) | |

| − ARVC | 5 (11.1) | 2 (6.2) | 3 (23.1) | 0.162 |

| − Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 5 (11.1) | 5 (15.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| − Lamin A/C mutation cardiomyopathy | 3 (6.7) | 3 (9.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| − Congenital cardiomyopathy | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | |

| Implantable cardioverter defibrillator | 41 (91.1) | 31 (96.9) | 10 (76.9) | 0.066 |

| − Secondary prevention | 21 (46.7) | 17 (53.1) | 4 (30.8) | 0.302 |

| − Single chamber | 10 (22.2) | 8 (25.0) | 2 (15.4) | |

| − Dual chamber | 8 (17.8) | 5 (15.6) | 3 (23.1) | 0.302 |

| − Resynchronization therapy | 13 (28.9) | 10 (31.2) | 3 (23.1) | |

| − Subcutaneous ICD | 1 (2.2) | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| History of ventricular arrhythmia | 32 (71.1) | 24 (75.0) | 8 (61.5) | 0.473 |

| History of ES | 12 (26.7) | 8 (25.0) | 4 (30.8) | 0.721 |

| History of VT ablation | 12 (26.7) | 8 (25.0) | 4 (30.8) | 0.721 |

| LVEF, % | 25.0 (20.0–34.3) | 26.5 (24.5–34.5) | 25.0 (18.8–33.0) | 0.325 |

| LVAD | 3 (6.7) | 2 (6.3) | 1 (7.7) | 1.000 |

| Usual treatment prior to ES: | ||||

| − Beta blockers | 40 (88.9) | 29 (90.6) | 11 (84.6) | 0.617 |

| − Amiodarone | 22 (48.9) | 13 (40.6) | 9 (69.2) | 0.108 |

| − ACEI/ARB | 25 (55.6) | 18 (56.3) | 7 (53.8) | 0.854 |

| − Sacubitril/valsartan | 11 (24.4) | 10 (31.2) | 1 (7.7) | 0.136 |

| − MRA | 19 (42.2) | 16 (50.0) | 3 (23.1) | 0.182 |

| − Diuretic agents | 31 (68.9) | 21 (65.6) | 10 (76.9) | 0.724 |

| − Anticoagulant | 25 (55.6) | 19 (59.4) | 6 (46.2) | 0.515 |

| − Antiplatelet agents | 11 (24.4) | 7 (21.9) | 4 (30.8) | 0.704 |

| − Statin | 13 (28.9) | 9 (28.1) | 4 (30.8) | 1.000 |

| Time from cardiomyopathy diagnosis to ES (years) | 11.0 (5.0–16.5) | 12 (5.0–18.5) | 9 (5.8–12.5) | 0.490 |

| . | All patients (n = 45) . | Patients alive at hospital discharge (n = 32) . | Patients died during hospitalization (n = 13) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 55.0 (47.8–59.3) | 53.5 (47.5–59.0) | 58.0 (50.0–63.5) | 0.259 |

| Male gender | 37 (82.2) | 26 (81.2) | 11 (84.6) | 1.000 |

| Body mass index, kg/m² | 26.6 ± 4.1 | 26.2 ± 3.9 | 27.7 ± 4.5 | 0.248 |

| Hypertension | 17 (37.8) | 12 (37.5) | 5 (38.5) | 1.000 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 6 (13.3) | 3 (9.4) | 3 (23.1) | 0.334 |

| Dyslipidemia | 10 (22.2) | 8 (25.0) | 2 (15.4) | 0.698 |

| History of smoking | 17 (37.8) | 12 (37.5) | 5 (38.5) | 1.000 |

| Heredity | 2 (4.4) | 2 (6.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| Cardiomyopathy: | ||||

| − Non-ischaemic dilated cardiomyopathy | 19 (42.2) | 14 (43.8) | 5 (38.5) | |

| − Ischaemic cardiomyopathy | 12 (26.7) | 8 (25.0) | 4 (30.8) | |

| − ARVC | 5 (11.1) | 2 (6.2) | 3 (23.1) | 0.162 |

| − Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 5 (11.1) | 5 (15.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| − Lamin A/C mutation cardiomyopathy | 3 (6.7) | 3 (9.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| − Congenital cardiomyopathy | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | |

| Implantable cardioverter defibrillator | 41 (91.1) | 31 (96.9) | 10 (76.9) | 0.066 |

| − Secondary prevention | 21 (46.7) | 17 (53.1) | 4 (30.8) | 0.302 |

| − Single chamber | 10 (22.2) | 8 (25.0) | 2 (15.4) | |

| − Dual chamber | 8 (17.8) | 5 (15.6) | 3 (23.1) | 0.302 |

| − Resynchronization therapy | 13 (28.9) | 10 (31.2) | 3 (23.1) | |

| − Subcutaneous ICD | 1 (2.2) | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| History of ventricular arrhythmia | 32 (71.1) | 24 (75.0) | 8 (61.5) | 0.473 |

| History of ES | 12 (26.7) | 8 (25.0) | 4 (30.8) | 0.721 |

| History of VT ablation | 12 (26.7) | 8 (25.0) | 4 (30.8) | 0.721 |

| LVEF, % | 25.0 (20.0–34.3) | 26.5 (24.5–34.5) | 25.0 (18.8–33.0) | 0.325 |

| LVAD | 3 (6.7) | 2 (6.3) | 1 (7.7) | 1.000 |

| Usual treatment prior to ES: | ||||

| − Beta blockers | 40 (88.9) | 29 (90.6) | 11 (84.6) | 0.617 |

| − Amiodarone | 22 (48.9) | 13 (40.6) | 9 (69.2) | 0.108 |

| − ACEI/ARB | 25 (55.6) | 18 (56.3) | 7 (53.8) | 0.854 |

| − Sacubitril/valsartan | 11 (24.4) | 10 (31.2) | 1 (7.7) | 0.136 |

| − MRA | 19 (42.2) | 16 (50.0) | 3 (23.1) | 0.182 |

| − Diuretic agents | 31 (68.9) | 21 (65.6) | 10 (76.9) | 0.724 |

| − Anticoagulant | 25 (55.6) | 19 (59.4) | 6 (46.2) | 0.515 |

| − Antiplatelet agents | 11 (24.4) | 7 (21.9) | 4 (30.8) | 0.704 |

| − Statin | 13 (28.9) | 9 (28.1) | 4 (30.8) | 1.000 |

| Time from cardiomyopathy diagnosis to ES (years) | 11.0 (5.0–16.5) | 12 (5.0–18.5) | 9 (5.8–12.5) | 0.490 |

ACEI/ARB, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker; ARVC, arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy; ES, electrical storm; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

To note, among the 45 patients included, 9 (20%) patients were already registered on elective transplantation list, while the remaining 36 (80%) were not on transplantation list at the time of ES onset.

Characteristics and management of electrical storm before registration on the heart transplantation waiting list

The characteristics and management of ES are summarized in Table 2. A triggering event was found in 17 patients (37.8%), mainly heart failure. Less than five electrical shocks were administered in 22 patients (48.9%), while 13 (28.9%) had more than 10 shocks. The anti-arrhythmic drugs administered at the time of ES onset were mainly amiodarone (42 patients, 93.3%), beta blockers (29 patients, 64.4%; mainly esmolol, bisoprolol, and nadolol), lidocaine (21 patients, 46.7%), and magnesium sulfate (22 patients, 48.9%). Despite the use of anti-arrhythmic drugs, ES persisted leading to deep sedation in 19 patients (42.2%), and/or haemodynamic support [extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) or intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP)] in 22 patients (48.9%). Of note, neuraxial modulation using percutaneous stellate ganglion block was performed in one patient (2.2%), and nine patients (20.0%) benefitted from VT ablation. The mean time between presentation for ES and the ablation procedure was 3.6 ± 2.7days. All procedures were performed using an endocardial approach, and only two patients (22.2%) had a combined endo-epicardial procedure. The procedure was performed under general anaesthesia in four patients (44.4%), while none was performed under haemodynamic support. More than two different VT morphologies were induced in six of the nine patients (66.7%). The mean radiofrequency time was 22 ± 17.9 min, and four patients (44.4%) were non-inducible at the end of the procedure.

| . | All patients (n = 45) . | Patients alive at hospital discharge (n = 32) . | Patients died during hospitalization (n = 13) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of shocks for ES: | ||||

| − <5 shocks | 24 (53.3) | 17 (53.1) | 7 (53.8) | |

| − 5–10 shocks | 8 (17.8) | 5 (15.6) | 3 (23.1) | 0.825 |

| − >10 shocks | 13 (28.9) | 10 (31.2) | 3 (23.1) | |

| Trigger factor: | 17 (37.8) | 12 (37.5) | 5 (38.5) | 1.000 |

| − Heart failure | 11 (24.4) | 7 (15.6) | 4 (30.8) | 0.244 |

| − Hypokalaemia | 3 (6.7) | 2 (6.3) | 1 (7.7) | 1.000 |

| − Acute coronary syndrome | 3 (6.7) | 2 (6.3) | 1 (7.7) | 1.000 |

| − Infection | 1 (2.2) | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| − Anti-arrhythmic drugs interruption and hyperthyroidism | 1 (2.2) | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| − VT ablation | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 0.289 |

| Anti-arrhythmic drugs used: | ||||

| − Beta blockers | 29 (64.4) | 21 (65.6) | 8 (61.5) | 1.000 |

| − Amiodarone | 42 (93.3) | 30 (93.8) | 12 (92.3) | 1.000 |

| − Lidocaine | 21 (46.7) | 16 (50.0) | 5 (38.5) | 0.528 |

| − Flecainide | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 0.289 |

| − Magnesium sulfate | 22 (48.9) | 16 (50.0) | 6 (46.2) | 1.000 |

| Deep sedation | 19 (42.2) | 14 (43.8) | 5 (38.5) | 1.000 |

| Invasive haemodynamic support | 22 (48.9) | 16 (50.0) | 6 (46.2) | 1.000 |

| − ECMO | 16 (35.6) | 12 (37.5) | 4 (30.8) | 0.743 |

| − IABP | 6 (13.3) | 4 (12.5) | 2 (15.4) | 1.000 |

| VT ablation | 9 (20.0) | 5 (15.6) | 4 (30.8) | 0.411 |

| Neuraxial modulation (stellate ganglion blockade) | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 0.289 |

| . | All patients (n = 45) . | Patients alive at hospital discharge (n = 32) . | Patients died during hospitalization (n = 13) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of shocks for ES: | ||||

| − <5 shocks | 24 (53.3) | 17 (53.1) | 7 (53.8) | |

| − 5–10 shocks | 8 (17.8) | 5 (15.6) | 3 (23.1) | 0.825 |

| − >10 shocks | 13 (28.9) | 10 (31.2) | 3 (23.1) | |

| Trigger factor: | 17 (37.8) | 12 (37.5) | 5 (38.5) | 1.000 |

| − Heart failure | 11 (24.4) | 7 (15.6) | 4 (30.8) | 0.244 |

| − Hypokalaemia | 3 (6.7) | 2 (6.3) | 1 (7.7) | 1.000 |

| − Acute coronary syndrome | 3 (6.7) | 2 (6.3) | 1 (7.7) | 1.000 |

| − Infection | 1 (2.2) | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| − Anti-arrhythmic drugs interruption and hyperthyroidism | 1 (2.2) | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| − VT ablation | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 0.289 |

| Anti-arrhythmic drugs used: | ||||

| − Beta blockers | 29 (64.4) | 21 (65.6) | 8 (61.5) | 1.000 |

| − Amiodarone | 42 (93.3) | 30 (93.8) | 12 (92.3) | 1.000 |

| − Lidocaine | 21 (46.7) | 16 (50.0) | 5 (38.5) | 0.528 |

| − Flecainide | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 0.289 |

| − Magnesium sulfate | 22 (48.9) | 16 (50.0) | 6 (46.2) | 1.000 |

| Deep sedation | 19 (42.2) | 14 (43.8) | 5 (38.5) | 1.000 |

| Invasive haemodynamic support | 22 (48.9) | 16 (50.0) | 6 (46.2) | 1.000 |

| − ECMO | 16 (35.6) | 12 (37.5) | 4 (30.8) | 0.743 |

| − IABP | 6 (13.3) | 4 (12.5) | 2 (15.4) | 1.000 |

| VT ablation | 9 (20.0) | 5 (15.6) | 4 (30.8) | 0.411 |

| Neuraxial modulation (stellate ganglion blockade) | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 0.289 |

ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ES, electrical storm; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

| . | All patients (n = 45) . | Patients alive at hospital discharge (n = 32) . | Patients died during hospitalization (n = 13) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of shocks for ES: | ||||

| − <5 shocks | 24 (53.3) | 17 (53.1) | 7 (53.8) | |

| − 5–10 shocks | 8 (17.8) | 5 (15.6) | 3 (23.1) | 0.825 |

| − >10 shocks | 13 (28.9) | 10 (31.2) | 3 (23.1) | |

| Trigger factor: | 17 (37.8) | 12 (37.5) | 5 (38.5) | 1.000 |

| − Heart failure | 11 (24.4) | 7 (15.6) | 4 (30.8) | 0.244 |

| − Hypokalaemia | 3 (6.7) | 2 (6.3) | 1 (7.7) | 1.000 |

| − Acute coronary syndrome | 3 (6.7) | 2 (6.3) | 1 (7.7) | 1.000 |

| − Infection | 1 (2.2) | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| − Anti-arrhythmic drugs interruption and hyperthyroidism | 1 (2.2) | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| − VT ablation | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 0.289 |

| Anti-arrhythmic drugs used: | ||||

| − Beta blockers | 29 (64.4) | 21 (65.6) | 8 (61.5) | 1.000 |

| − Amiodarone | 42 (93.3) | 30 (93.8) | 12 (92.3) | 1.000 |

| − Lidocaine | 21 (46.7) | 16 (50.0) | 5 (38.5) | 0.528 |

| − Flecainide | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 0.289 |

| − Magnesium sulfate | 22 (48.9) | 16 (50.0) | 6 (46.2) | 1.000 |

| Deep sedation | 19 (42.2) | 14 (43.8) | 5 (38.5) | 1.000 |

| Invasive haemodynamic support | 22 (48.9) | 16 (50.0) | 6 (46.2) | 1.000 |

| − ECMO | 16 (35.6) | 12 (37.5) | 4 (30.8) | 0.743 |

| − IABP | 6 (13.3) | 4 (12.5) | 2 (15.4) | 1.000 |

| VT ablation | 9 (20.0) | 5 (15.6) | 4 (30.8) | 0.411 |

| Neuraxial modulation (stellate ganglion blockade) | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 0.289 |

| . | All patients (n = 45) . | Patients alive at hospital discharge (n = 32) . | Patients died during hospitalization (n = 13) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of shocks for ES: | ||||

| − <5 shocks | 24 (53.3) | 17 (53.1) | 7 (53.8) | |

| − 5–10 shocks | 8 (17.8) | 5 (15.6) | 3 (23.1) | 0.825 |

| − >10 shocks | 13 (28.9) | 10 (31.2) | 3 (23.1) | |

| Trigger factor: | 17 (37.8) | 12 (37.5) | 5 (38.5) | 1.000 |

| − Heart failure | 11 (24.4) | 7 (15.6) | 4 (30.8) | 0.244 |

| − Hypokalaemia | 3 (6.7) | 2 (6.3) | 1 (7.7) | 1.000 |

| − Acute coronary syndrome | 3 (6.7) | 2 (6.3) | 1 (7.7) | 1.000 |

| − Infection | 1 (2.2) | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| − Anti-arrhythmic drugs interruption and hyperthyroidism | 1 (2.2) | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| − VT ablation | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 0.289 |

| Anti-arrhythmic drugs used: | ||||

| − Beta blockers | 29 (64.4) | 21 (65.6) | 8 (61.5) | 1.000 |

| − Amiodarone | 42 (93.3) | 30 (93.8) | 12 (92.3) | 1.000 |

| − Lidocaine | 21 (46.7) | 16 (50.0) | 5 (38.5) | 0.528 |

| − Flecainide | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 0.289 |

| − Magnesium sulfate | 22 (48.9) | 16 (50.0) | 6 (46.2) | 1.000 |

| Deep sedation | 19 (42.2) | 14 (43.8) | 5 (38.5) | 1.000 |

| Invasive haemodynamic support | 22 (48.9) | 16 (50.0) | 6 (46.2) | 1.000 |

| − ECMO | 16 (35.6) | 12 (37.5) | 4 (30.8) | 0.743 |

| − IABP | 6 (13.3) | 4 (12.5) | 2 (15.4) | 1.000 |

| VT ablation | 9 (20.0) | 5 (15.6) | 4 (30.8) | 0.411 |

| Neuraxial modulation (stellate ganglion blockade) | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 0.289 |

ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ES, electrical storm; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Procedural data

The clinical and biological parameters before HT are described in Table 3. A total of 28 patients (62.2%) were in cardiogenic shock. Vasoactive drugs were administered in 19 patients (42.2%). The median LVEF decreased to 20.0% (15.0–25.0). The median serum creatinine and total bilirubin levels were 106.0 μmol/L (93.5–150.0) and 14.0 μmol/L (8.8–24.8), respectively.

Clinical and biological status before HT and transplantation characteristics

| . | All patients (n = 45) . | Patients alive at hospital discharge (n = 32) . | Patients died during hospitalization (n = 13) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiogenic shock | 28 (62.2) | 21 (65.6) | 7 (53.8) | 0.511 |

| Vasporessor and inotropic drugs: | 19 (42.2) | 14 (43.8) | 5 (38.5) | 1.000 |

| − Epinephrine | 1 (2 .2) | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| − Norepinephrine | 10 (22.2) | 6 (18.8) | 4 (30.8) | 0.427 |

| − Dobutamine | 19 (42.2) | 14 (43.8) | 5 (38.5) | 1.000 |

| LVEF at the time of transplantation, % | 20.0 (15.0–25.0) | 20.0 (15.0–25.0) | 20.0 (13.8–22.5) | 0.629 |

| Laboratory parameters: | ||||

| − Serum sodium, mmol/L (n = 34) | 136.5 ± 4.9 | 135.6 ± 4.6 | 138.5 ± 5.1 | 0.098 |

| − Serum creatinine, µmol/L (n = 36) | 106.0 (93.5–150.0) | 100.0 (90.5–122.0) | 151.0 (103.0–196.0) | 0.008 |

| − Serum total bilirubin, µmol/L (n = 29) | 14.0 (8.8–24.8) | 12.0 (9.3–22.5) | 18.5 (7.0–46.0) | 0.505 |

| − Serum urea, mmol/L (n = 30) | 9.7 (5.9–13.0) | 8.0 (5.6–10.0) | 13.0 (10.6–19.8) | 0.019 |

| − Serum lactate, mmol/L (n = 17) | 1.2 (1.0–2.2) | 1.2 (1.0–2.0) | 1.5 (0.9–4.3) | 0.820 |

| Delay between ES and transplant list inscription (or switch on super-urgent list) (days) | 3.0 (1.0–5.0) | 2.0 (1.0–4.5) | 4.0 (1.0–6.3) | 0.190 |

| Delay between transplant list inscription and HT (days) | 5.0 (2.0–13.3) | 3.5 (2.0–13.0) | 6.0 (2.0–30.5) | 0.301 |

| Immediate ECMO support after HT | 20 (44.4) | 11 (34.4) | 9 (69.2) | 0.049 |

| . | All patients (n = 45) . | Patients alive at hospital discharge (n = 32) . | Patients died during hospitalization (n = 13) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiogenic shock | 28 (62.2) | 21 (65.6) | 7 (53.8) | 0.511 |

| Vasporessor and inotropic drugs: | 19 (42.2) | 14 (43.8) | 5 (38.5) | 1.000 |

| − Epinephrine | 1 (2 .2) | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| − Norepinephrine | 10 (22.2) | 6 (18.8) | 4 (30.8) | 0.427 |

| − Dobutamine | 19 (42.2) | 14 (43.8) | 5 (38.5) | 1.000 |

| LVEF at the time of transplantation, % | 20.0 (15.0–25.0) | 20.0 (15.0–25.0) | 20.0 (13.8–22.5) | 0.629 |

| Laboratory parameters: | ||||

| − Serum sodium, mmol/L (n = 34) | 136.5 ± 4.9 | 135.6 ± 4.6 | 138.5 ± 5.1 | 0.098 |

| − Serum creatinine, µmol/L (n = 36) | 106.0 (93.5–150.0) | 100.0 (90.5–122.0) | 151.0 (103.0–196.0) | 0.008 |

| − Serum total bilirubin, µmol/L (n = 29) | 14.0 (8.8–24.8) | 12.0 (9.3–22.5) | 18.5 (7.0–46.0) | 0.505 |

| − Serum urea, mmol/L (n = 30) | 9.7 (5.9–13.0) | 8.0 (5.6–10.0) | 13.0 (10.6–19.8) | 0.019 |

| − Serum lactate, mmol/L (n = 17) | 1.2 (1.0–2.2) | 1.2 (1.0–2.0) | 1.5 (0.9–4.3) | 0.820 |

| Delay between ES and transplant list inscription (or switch on super-urgent list) (days) | 3.0 (1.0–5.0) | 2.0 (1.0–4.5) | 4.0 (1.0–6.3) | 0.190 |

| Delay between transplant list inscription and HT (days) | 5.0 (2.0–13.3) | 3.5 (2.0–13.0) | 6.0 (2.0–30.5) | 0.301 |

| Immediate ECMO support after HT | 20 (44.4) | 11 (34.4) | 9 (69.2) | 0.049 |

ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ES, electrical storm; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Clinical and biological status before HT and transplantation characteristics

| . | All patients (n = 45) . | Patients alive at hospital discharge (n = 32) . | Patients died during hospitalization (n = 13) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiogenic shock | 28 (62.2) | 21 (65.6) | 7 (53.8) | 0.511 |

| Vasporessor and inotropic drugs: | 19 (42.2) | 14 (43.8) | 5 (38.5) | 1.000 |

| − Epinephrine | 1 (2 .2) | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| − Norepinephrine | 10 (22.2) | 6 (18.8) | 4 (30.8) | 0.427 |

| − Dobutamine | 19 (42.2) | 14 (43.8) | 5 (38.5) | 1.000 |

| LVEF at the time of transplantation, % | 20.0 (15.0–25.0) | 20.0 (15.0–25.0) | 20.0 (13.8–22.5) | 0.629 |

| Laboratory parameters: | ||||

| − Serum sodium, mmol/L (n = 34) | 136.5 ± 4.9 | 135.6 ± 4.6 | 138.5 ± 5.1 | 0.098 |

| − Serum creatinine, µmol/L (n = 36) | 106.0 (93.5–150.0) | 100.0 (90.5–122.0) | 151.0 (103.0–196.0) | 0.008 |

| − Serum total bilirubin, µmol/L (n = 29) | 14.0 (8.8–24.8) | 12.0 (9.3–22.5) | 18.5 (7.0–46.0) | 0.505 |

| − Serum urea, mmol/L (n = 30) | 9.7 (5.9–13.0) | 8.0 (5.6–10.0) | 13.0 (10.6–19.8) | 0.019 |

| − Serum lactate, mmol/L (n = 17) | 1.2 (1.0–2.2) | 1.2 (1.0–2.0) | 1.5 (0.9–4.3) | 0.820 |

| Delay between ES and transplant list inscription (or switch on super-urgent list) (days) | 3.0 (1.0–5.0) | 2.0 (1.0–4.5) | 4.0 (1.0–6.3) | 0.190 |

| Delay between transplant list inscription and HT (days) | 5.0 (2.0–13.3) | 3.5 (2.0–13.0) | 6.0 (2.0–30.5) | 0.301 |

| Immediate ECMO support after HT | 20 (44.4) | 11 (34.4) | 9 (69.2) | 0.049 |

| . | All patients (n = 45) . | Patients alive at hospital discharge (n = 32) . | Patients died during hospitalization (n = 13) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiogenic shock | 28 (62.2) | 21 (65.6) | 7 (53.8) | 0.511 |

| Vasporessor and inotropic drugs: | 19 (42.2) | 14 (43.8) | 5 (38.5) | 1.000 |

| − Epinephrine | 1 (2 .2) | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| − Norepinephrine | 10 (22.2) | 6 (18.8) | 4 (30.8) | 0.427 |

| − Dobutamine | 19 (42.2) | 14 (43.8) | 5 (38.5) | 1.000 |

| LVEF at the time of transplantation, % | 20.0 (15.0–25.0) | 20.0 (15.0–25.0) | 20.0 (13.8–22.5) | 0.629 |

| Laboratory parameters: | ||||

| − Serum sodium, mmol/L (n = 34) | 136.5 ± 4.9 | 135.6 ± 4.6 | 138.5 ± 5.1 | 0.098 |

| − Serum creatinine, µmol/L (n = 36) | 106.0 (93.5–150.0) | 100.0 (90.5–122.0) | 151.0 (103.0–196.0) | 0.008 |

| − Serum total bilirubin, µmol/L (n = 29) | 14.0 (8.8–24.8) | 12.0 (9.3–22.5) | 18.5 (7.0–46.0) | 0.505 |

| − Serum urea, mmol/L (n = 30) | 9.7 (5.9–13.0) | 8.0 (5.6–10.0) | 13.0 (10.6–19.8) | 0.019 |

| − Serum lactate, mmol/L (n = 17) | 1.2 (1.0–2.2) | 1.2 (1.0–2.0) | 1.5 (0.9–4.3) | 0.820 |

| Delay between ES and transplant list inscription (or switch on super-urgent list) (days) | 3.0 (1.0–5.0) | 2.0 (1.0–4.5) | 4.0 (1.0–6.3) | 0.190 |

| Delay between transplant list inscription and HT (days) | 5.0 (2.0–13.3) | 3.5 (2.0–13.0) | 6.0 (2.0–30.5) | 0.301 |

| Immediate ECMO support after HT | 20 (44.4) | 11 (34.4) | 9 (69.2) | 0.049 |

ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ES, electrical storm; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Median times of 3 days (1.0–5.0) and 5 days (2.0–13.3) were observed between the ES onset and the listing on transplant wait list, and between the wait listing and the HT, respectively. Consequently, transplantation occurred after a median of 9.0 (4.0–14.0) days after ES onset. Twenty patients (44.4%) needed immediate haemodynamic support at the end of transplant surgery.

After HT, 32 (71.1%) patients suffered complications during their stay in Intensive Care Unit, mainly primary graft dysfunction (20 patients, 44.4%), acute kidney injury (18 patients, 40.0%), infection (16 patients, 35.6%), and right ventricular dysfunction (11 patients, 24.4%). A surgical re-intervention was required in 20 patients (44.4%), mainly for pericardial drainage (14 patients, 31.1%), ECMO removal (7 patients, 15.6%), and other surgeries (8 patients, 17.8%, revision surgery for sternal or mediastinal infections, hemothorax drainage, and superior vena cava syndrome requiring angioplasty or prosthesis implantation) (Table 4).

| . | All patients (n = 45) . | Patients alive at hospital discharge (n = 32) . | Patients died during hospitalization (n = 13) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complications in ICU: | ||||

| − All | 32 (71.1) | 19 (59.4) | 13 (100.0) | 0.009 |

| − Primary graft dysfunction | 20 (44.4) | 9 (28.1) | 11 (84.6) | 0.001 |

| − Right ventricular dysfunction | 11 (24.4) | 8 (25.0) | 3 (23.1) | 1.000 |

| − Graft acute rejection | 2 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (15.4) | 0.023 |

| − Supra-ventricular arrhythmia | 3 (6.7) | 1 (3.1) | 2 (15.4) | 0.196 |

| − Infection | 16 (35.6) | 11 (34.4) | 5 (38.5) | 1.000 |

| − Acute kidney injury | 18 (40.0) | 12 (37.5) | 6 (46.2) | 0.739 |

| − Peripheral neuropathy | 2 (4.4) | 1 (3.1) | 1 (7.7) | 0.499 |

| − Thrombotic | 3 (6.7) | 2 (6.2) | 1 (7.7) | 1.000 |

| − Haemorrhagic | 3 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (23.1) | 0.020 |

| − Tracheostomy | 2 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (15.4) | 0.079 |

| Surgical re-interventions: | ||||

| − All | 20 (44.4) | 11 (34.4) | 9 (69.2) | 0.049 |

| − Pericardial drainage | 14 (31.1) | 6 (18.8) | 8 (61.5) | 0.011 |

| − ECMO removal | 7 (15.6) | 5 (15.6) | 2 (15.4) | 1.000 |

| − ECMO implantation | 2 (4.4) | 1 (3.1) | 1 (7.7) | 0.499 |

| − ECMO implantation site complications | 1 (2.2) | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| − Others | 8 (17.8) | 3 (9.4) | 5 (38.5) | 0.034 |

| ICU length of stay (days) | 16.0 (9.5–32.3) | 16.0 (11.0–24.0) | 6.0 (1.0–61.8) | 0.416 |

| Total hospitalization length of stay (days) | 33.0 (23.0–56.5) | 34.0 (27.0–49.0) | 6.0 (1.0–62.5) | 0.165 |

| . | All patients (n = 45) . | Patients alive at hospital discharge (n = 32) . | Patients died during hospitalization (n = 13) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complications in ICU: | ||||

| − All | 32 (71.1) | 19 (59.4) | 13 (100.0) | 0.009 |

| − Primary graft dysfunction | 20 (44.4) | 9 (28.1) | 11 (84.6) | 0.001 |

| − Right ventricular dysfunction | 11 (24.4) | 8 (25.0) | 3 (23.1) | 1.000 |

| − Graft acute rejection | 2 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (15.4) | 0.023 |

| − Supra-ventricular arrhythmia | 3 (6.7) | 1 (3.1) | 2 (15.4) | 0.196 |

| − Infection | 16 (35.6) | 11 (34.4) | 5 (38.5) | 1.000 |

| − Acute kidney injury | 18 (40.0) | 12 (37.5) | 6 (46.2) | 0.739 |

| − Peripheral neuropathy | 2 (4.4) | 1 (3.1) | 1 (7.7) | 0.499 |

| − Thrombotic | 3 (6.7) | 2 (6.2) | 1 (7.7) | 1.000 |

| − Haemorrhagic | 3 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (23.1) | 0.020 |

| − Tracheostomy | 2 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (15.4) | 0.079 |

| Surgical re-interventions: | ||||

| − All | 20 (44.4) | 11 (34.4) | 9 (69.2) | 0.049 |

| − Pericardial drainage | 14 (31.1) | 6 (18.8) | 8 (61.5) | 0.011 |

| − ECMO removal | 7 (15.6) | 5 (15.6) | 2 (15.4) | 1.000 |

| − ECMO implantation | 2 (4.4) | 1 (3.1) | 1 (7.7) | 0.499 |

| − ECMO implantation site complications | 1 (2.2) | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| − Others | 8 (17.8) | 3 (9.4) | 5 (38.5) | 0.034 |

| ICU length of stay (days) | 16.0 (9.5–32.3) | 16.0 (11.0–24.0) | 6.0 (1.0–61.8) | 0.416 |

| Total hospitalization length of stay (days) | 33.0 (23.0–56.5) | 34.0 (27.0–49.0) | 6.0 (1.0–62.5) | 0.165 |

ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ICU, intensive care unit.

| . | All patients (n = 45) . | Patients alive at hospital discharge (n = 32) . | Patients died during hospitalization (n = 13) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complications in ICU: | ||||

| − All | 32 (71.1) | 19 (59.4) | 13 (100.0) | 0.009 |

| − Primary graft dysfunction | 20 (44.4) | 9 (28.1) | 11 (84.6) | 0.001 |

| − Right ventricular dysfunction | 11 (24.4) | 8 (25.0) | 3 (23.1) | 1.000 |

| − Graft acute rejection | 2 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (15.4) | 0.023 |

| − Supra-ventricular arrhythmia | 3 (6.7) | 1 (3.1) | 2 (15.4) | 0.196 |

| − Infection | 16 (35.6) | 11 (34.4) | 5 (38.5) | 1.000 |

| − Acute kidney injury | 18 (40.0) | 12 (37.5) | 6 (46.2) | 0.739 |

| − Peripheral neuropathy | 2 (4.4) | 1 (3.1) | 1 (7.7) | 0.499 |

| − Thrombotic | 3 (6.7) | 2 (6.2) | 1 (7.7) | 1.000 |

| − Haemorrhagic | 3 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (23.1) | 0.020 |

| − Tracheostomy | 2 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (15.4) | 0.079 |

| Surgical re-interventions: | ||||

| − All | 20 (44.4) | 11 (34.4) | 9 (69.2) | 0.049 |

| − Pericardial drainage | 14 (31.1) | 6 (18.8) | 8 (61.5) | 0.011 |

| − ECMO removal | 7 (15.6) | 5 (15.6) | 2 (15.4) | 1.000 |

| − ECMO implantation | 2 (4.4) | 1 (3.1) | 1 (7.7) | 0.499 |

| − ECMO implantation site complications | 1 (2.2) | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| − Others | 8 (17.8) | 3 (9.4) | 5 (38.5) | 0.034 |

| ICU length of stay (days) | 16.0 (9.5–32.3) | 16.0 (11.0–24.0) | 6.0 (1.0–61.8) | 0.416 |

| Total hospitalization length of stay (days) | 33.0 (23.0–56.5) | 34.0 (27.0–49.0) | 6.0 (1.0–62.5) | 0.165 |

| . | All patients (n = 45) . | Patients alive at hospital discharge (n = 32) . | Patients died during hospitalization (n = 13) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complications in ICU: | ||||

| − All | 32 (71.1) | 19 (59.4) | 13 (100.0) | 0.009 |

| − Primary graft dysfunction | 20 (44.4) | 9 (28.1) | 11 (84.6) | 0.001 |

| − Right ventricular dysfunction | 11 (24.4) | 8 (25.0) | 3 (23.1) | 1.000 |

| − Graft acute rejection | 2 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (15.4) | 0.023 |

| − Supra-ventricular arrhythmia | 3 (6.7) | 1 (3.1) | 2 (15.4) | 0.196 |

| − Infection | 16 (35.6) | 11 (34.4) | 5 (38.5) | 1.000 |

| − Acute kidney injury | 18 (40.0) | 12 (37.5) | 6 (46.2) | 0.739 |

| − Peripheral neuropathy | 2 (4.4) | 1 (3.1) | 1 (7.7) | 0.499 |

| − Thrombotic | 3 (6.7) | 2 (6.2) | 1 (7.7) | 1.000 |

| − Haemorrhagic | 3 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (23.1) | 0.020 |

| − Tracheostomy | 2 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (15.4) | 0.079 |

| Surgical re-interventions: | ||||

| − All | 20 (44.4) | 11 (34.4) | 9 (69.2) | 0.049 |

| − Pericardial drainage | 14 (31.1) | 6 (18.8) | 8 (61.5) | 0.011 |

| − ECMO removal | 7 (15.6) | 5 (15.6) | 2 (15.4) | 1.000 |

| − ECMO implantation | 2 (4.4) | 1 (3.1) | 1 (7.7) | 0.499 |

| − ECMO implantation site complications | 1 (2.2) | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| − Others | 8 (17.8) | 3 (9.4) | 5 (38.5) | 0.034 |

| ICU length of stay (days) | 16.0 (9.5–32.3) | 16.0 (11.0–24.0) | 6.0 (1.0–61.8) | 0.416 |

| Total hospitalization length of stay (days) | 33.0 (23.0–56.5) | 34.0 (27.0–49.0) | 6.0 (1.0–62.5) | 0.165 |

ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ICU, intensive care unit.

Factors associated with in-hospital mortality

Among the 45 patients studied, 13 (28.9%) died during the index hospitalization after a median of 6.0 (1.0–59.0) days, mainly from a non-cardiac cause (76.9%). The two leading causes of in-hospital deaths were pulmonary sepsis and cerebral haemorrhages. Survivors were discharged after 34.0 (27.5–48.8) days. Baseline characteristics of non-survivor patients were similar to those who survived (Table 1). Management of ES was similar between the two groups (Table 2). Patients alive at hospital discharge had significantly lower serum creatinine [100.0 (90.5–122.0) vs. 151.0 (103.0–196.0), P = 0.008] and urea [13.0 (10.6–19.8) vs. 8.0 (5.6–10.0), P = 0.019] levels before surgery compared with those who died. There were significantly more patients needing immediate haemodynamic support post-transplantation in the group of patients dead during hospitalization (69.2% vs. 34.4%, P = 0.049) (Table 3). All complications were significantly more frequent in the non-survivor group (100% vs. 59.4%, P = 0.009), as well as primary graft dysfunction (84.6% vs. 28.1%, P = 0.001), acute graft rejection (15.4% vs. 0.0%, P = 0.023), and haemorrhagic complications (23.1% vs. 0.0%, P = 0.020). There were also more surgical re-interventions in the non-survivor group (69.2% vs. 34.4%, P = 0.049), with more pericardial drainage (62.5% vs. 18.8%, P = 0.011) and other surgeries (38.5% vs. 9.4%, P = 0.034) (Table 4).

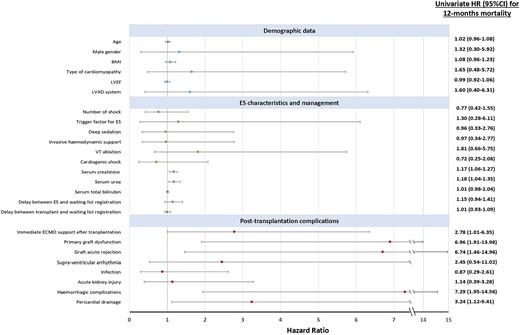

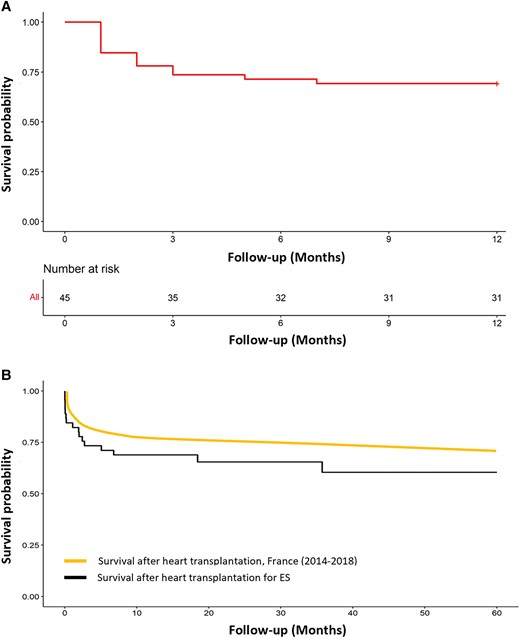

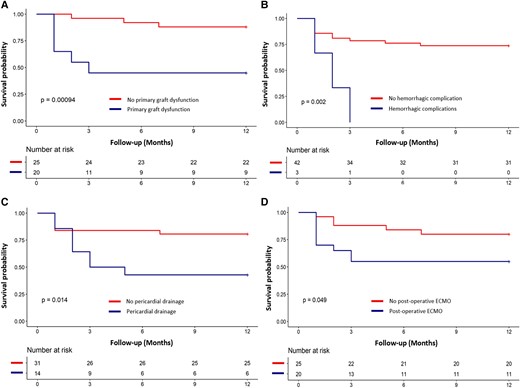

One year survival

Results of univariate Cox regression analysis for the 12-month mortality are illustrated in Figure 1. Predictive factors associated with mortality at 12 months were the same as the predictive factors of in-hospital mortality, confirming the major impact of the peri-operative period on the short-term survival. No demographic characteristics appeared to be related with the 12-month survival. Among the 45 patients who underwent HT for refractory ES, 31 patients (68.9%) were still alive at 12 months. Among the 14 patients who died during the first year, 13 died in hospital due to HT acute complications, and one patient died 7 months after hospital discharge from a non-cardiac cause. The Kaplan–Meier survival curve at 1 year for the overall cohort is shown in Figure 2A. Figure 2B illustrates the 5-year survival of patients transplanted in emergency for refractory ES (black curve) and the national French survival data after HT for all indications between 2004 and 2018 (orange curve).14Figure 3 represents Kaplan–Meier 1-year survival estimates according to primary graft dysfunction, immediate post-operative ECMO support, haemorrhagic complications, and pericardial drainage.

Hazard ratio plot of 12-month mortality risk factors in univariate analysis. BMI, body mass index; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ES, electrical storm; ICU, intensive care unit; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Kaplan–Meier survival estimates after heart transplantation. (A) One-year survival estimates after heart transplantation for electrical storm. (B) Five-year survival estimates after heart transplantation for electrical storm and after heart transplantation in France (all indications combined). ES, electrical storm.

Kaplan–Meier 1-year survival estimates depending on several mortality predictive factors: primary graft dysfunction (A), haemorrhagic complications (B), pericardial drainage (C), and immediate post-operative extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support (D). ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Anatomopathological study of native explanted hearts

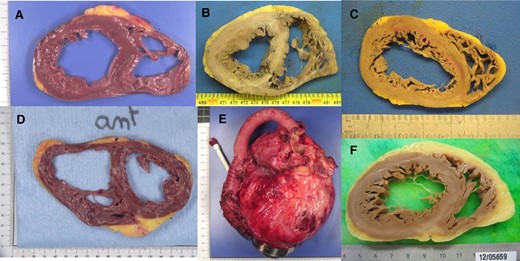

Anatomopathological examination of 23 explanted hearts (4 ischaemic and 19 non-ischaemic) was obtained. Most of the hearts showed areas of fibrosis (21 hearts, 91.3%), and 12 had cardiomyocyte abnormalities such as nuclear hypertrophy or dysmorphia (Figure 4). The two explanted hearts free from fibrosis had typical lesions of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy for one and left ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy for the other. Inflammatory lesions were noticed in six explanted hearts, with predominance of lymphocytes (in lamin A/C mutation, idiopathic and ischaemic cardiomyopathies), neutrophils (in ischaemic cardiomyopathy), eosinophils (in idiopathic cardiomyopathy, diagnosis of eosinophilic myocarditis, possibly the cardiomyopathy aetiology), and polymorphic cellular infiltrate (in idiopathic cardiomyopathy). Coronary atherosclerosis was observed (mainly non-stenosing) in 13 explanted hearts among the 19 patients suffering from non-ischaemic cardiomyopathies.

Anatomopathological study of explanted hearts. (A) Primary dilated cardiomyopathy, without overt fibrosis; (B and C) ischaemic cardiomyopathies with macroscopic fibrotic lesions; (D) lamin A/C mutation cardiomyopathy, in a patient with radiofrequency ablation failure (radiofrequency ablation lesions can be observed in the septal and lateral walls); (E) primary dilated cardiomyopathy with HeartMate 3; (F) primary dilated cardiomyopathy, with fibrosis in the posterior wall.

Discussion

Main results

The main results of this study are: (i) HT may be lifesaving in patients with intractable ES despite usual care. (ii) The post-operative period may be challenging: nearly half of the patients required immediate haemodynamic support after surgery, two-third experienced complications, and 44.4% required surgical re-interventions. (iii) In-hospital mortality rate was substantial, around 30%, and mortality predictors were closely linked to peri-operative conditions and post-operative complications.

Intractable electrical storm

The current definition of ES is based on the occurrence of at least three or more distinct episodes of sustained ventricular arrhythmias within 24 h or incessant ventricular arrhythmias for more than 12 h.1,2 In patients with ICD, ES is defined by the occurrence of more than three appropriate device therapies within 24 h, separated by at least 5 min.1,2,12 Such repetitive episodes can be well tolerated haemodynamically and managed through a multimodal approach associating anti-arrhythmic drugs, ICD reprogramming, correction of electrolyte imbalance, and VT catheter ablation. However, clinical presentation can sometimes be more complex, with repeated episodes of ventricular arrhythmias persisting despite optimal management, associated to haemodynamic instability. In those cases, usual management can consist in deep sedation, implantation of mechanical circulatory support (such as ECMO or IABP), or neuraxial modulation. Patient prognosis is very poor in the absence of restoration of a stable rhythm, free of arrhythmias.

The short-term survival in case of refractory ES is extremely compromised, specifically if patients are refractory to usual management.15 A mortality of 38%, 50%, and 75% has been described for those patients with refractory ES requiring deep sedation,16 ECMO,17 or LVAD,18 mainly due to multiple organ failure, right ventricular dysfunction, or recurrence of arrhythmias impacting short-term survival. The LVAD implantation in this context, specifically, is not a guarantee of survival, even though it provides haemodynamic stability.

Heart transplantation as a therapeutic strategy

If all treatments fail, the only remaining option to overcome this difficult situation and avoid death is HT. Only few case reports have been published thus far regarding this indication for transplantation.9–11 In those case reports, underlying cardiomyopathies were mainly idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy, arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia, and catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, and all patients survived after HT. This study including most of the French HT centres is the largest to describe the characteristics and outcomes of patients undergoing HT as a treatment for refractory ES. Among the study population included, a 68.9% 1-year survival was observed, more pejorative than in the case reports previously described but probably more representative of patients undergoing HT in an emergency context. The overall mortality was almost exclusively in-hospital mortality since all but one patient died during the index hospital stay.

One-year survival after HT in France from 2004 to 2018 was described at 77%.14 Similarly, the data from the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation, and the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients in USA reported better 1-year survival than the one observed in our study, at 85% and 89%, respectively.19,20 We assume that the lower survival rate observed in our study is probably related to the fact that national HT data include all indications for transplantation, and therefore mainly include elective transplantations. Conversely, the patients in this study were all transplanted in an emergency situation, which has already been shown to be a risk factor for mortality after HT.21–24 Lastly, in our cohort, 62% of the patients were in cardiogenic shock, and consequently nearly half had mechanical circulatory support, while 42% required inotrope drugs before transplantation, which is more than that reported in French transplanted patients globally.14

Mortality predictors after cardiac transplantation

As shown in our study, biological parameters indicative of organ failure have already been identified as risk factors for post-transplant mortality. Other main predictors of mortality after HT already identified are age, diabetes, mechanical circulatory support, mechanical ventilation, serum creatinine, and bilirubin levels.20,25–29

In our study, post-operative complications affected patient prognosis after HT. Indeed, several complications appear as mortality predictors: immediate ECMO support after HT, primary graft dysfunction, graft acute rejection, haemorrhagic complications, and pericardial drainage.

Primary graft dysfunction affected 44.4% of the patients included, a rate similar to the one observed for all HT in France in 2019.14 Other recent studies also identified this complication as a mortality predictor.30,31 On the other hand, ECMO support, a therapeutic strategy required for early graft dysfunction, is a mortality predictor by itself.32 It can be noticed that the proportion of patients needing an immediate post-operative haemodynamic support by ECMO is in line with French data.14 Predictors of early graft dysfunction requiring ECMO support are usually described as pre-operative ECMO, pre-operative inotropic drugs, and high transpulmonary gradient.32,33

Limitations

We acknowledge some limitations in our study. Our analysis was performed as a retrospective review of a cohort of patients transplanted in context of ES, with the inherent limitations of such studies. The number of patients included may appear limited. However, ES refractory to anti-arrhythmic drugs, ablation, neuraxial modulation, and all the usual care are rare, and consequently, only a limited number of 45 patients were included among the 11 participating centres. However, this work represents the largest study on this population published thus far.

Due to the limited sample size, multivariate analyses to eliminate confounding factors could not be performed. Furthermore, a lack of power to identify other predictors of in-hospital mortality cannot be excluded.

Lastly, only nine patients (20.0%) benefitted from VT ablation, which may seem limited, specifically in a population including mainly patients with structural heart diseases. We assume that this low rate of VT ablation is the consequence of the transplantation strategy chosen for the population study. Indeed, VT ablation is an invasive procedure, with inherent complications reaching 10% in ES patients.34 Some Heart Teams may have decided to avoid VT ablation and list patients for HT instead, thus avoiding unnecessary and potentially fatal complications. Similarly, only one patient had neuraxial modulation, reflecting the fact that this technic was poorly implemented in France during the inclusion period. Further studies would be necessary to better standardize ES management while patients are on the transplantation waiting list. Indeed, there is a critical lack of evidence regarding the best timing and indications of radiofrequency ablation, deep sedation, invasive haemodynamic support, and neuraxial modulation in patients with refractory ES.

Conclusion

Electrical storm is a rare indication of HT but may be lifesaving in those patients presenting intractable arrhythmias despite usual care. Most patients can be safely discharged from hospital, although post-operative mortality remains substantial in this context of emergency transplantation. Larger studies are warranted to precisely determine those patients at higher risk of in-hospital mortality.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

K.B. received a research grant from the Groupe de Rythmologie et Stimulation Cardiaque.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Author notes

Raphael P. Martins and Mathilde Hamel-Bougault contributed equally.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Comments