-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Anke Erdmann, Florian Schrinner, Christoph Rehmann-Sutter, Andre Franke, Ursula Seidler, Stefan Schreiber, Claudia Bozzaro, Acceptability Criteria of Precision Medicine: Lessons From Patients’ Experiences With the GUIDE-IBD Trial Regarding the Use of Mobile Health Technology, Crohn's & Colitis 360, Volume 5, Issue 4, October 2023, otad068, https://doi.org/10.1093/crocol/otad068

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Research about mobile health technologies for inflammatory bowel diseases reveals that these devices are mainly used to predict or self-report disease activity. However, in the near future these tools can be used to integrate large data sets into machine learning for the development of personalized treatment algorithms. The impact of these technologies on patients’ well-being and daily lives has not yet been investigated.

We conducted 10 qualitative interviews with patients who used the GUIDE-IBD mHealth technology. This is a special smartphone app for patients to record patient-reported outcomes and a wearable to track physical activity, heart rate, and sleep quality. For data analysis, we used interpretative phenomenological analysis. This method is ideally suited for studying people’s lived experiences.

The analysis of the data revealed 11 themes that were mentioned by at least 3 participants. These themes were: Self-tracking with wearable devices as normality; variable value of the data from the wearable; risk of putting people under pressure; stimulus to reflect on their own well-being and illness; risk of psychological distress; discussion about app data in the medical consultation is very brief or nonexistent; easier to be honest with an app than with a doctor; questionnaires do not always adequately capture the patient’s condition; need for support; the possibility to look at the data retrospectively; and annoyed by additional tasks.

Patients identified benefits, risks, and potentials for improvement, which should be considered in the further development of the devices and patient-reported outcome scales, and in the implementation of usual care.

Lay Summary

This study entails the results from interviews with patients suffering from IBD who used a new mobile health technology on a smartphone and smartwatch. Patients reported their experiences with the new app and with wearable, several benefits, but also risks.

So far, no research has been conducted on the experiences of patients with IBD using mobile health technologies and how this influences patients’ lives.

This qualitative interview study shows that patients benefit from the GUIDE-IBD mHealth technology, but they also see risks and potential for improvement.

The study provides helpful advice for developing and implementing mHealth technologies and adapting patient-reported outcomes to the needs of people with IBD.

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), including Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), are becoming more prevalent globally. Incidence rates are increasing in regions such as Asia, South America, and Africa where Western lifestyle habits are being adopted.1 IBD is caused by genetic, lifestyle, and environmental factors such as smoking, dietary habits, stress, exercise, microbiome composition, and UV radiation. All these factors influence the risk of disease.2 Since people are exposed to these factors to different degrees, the patients’ responses to therapy are individual, and side effects occur differently from person to person. For this reason, researchers are developing precision medicine (PM), which considers a person’s genetic characteristics, lifestyle, and environmental factors for therapy selection, offering the right medicine for the right patient, optimizing the drug dose, and thus minimizing possible side effects.3 However for developing PM, patients have to collect lifestyle and environmental factors.4 This may be more convenient and valid if data on physical activity, sleep, or stress are collected with a wearable that automatically records real-life data. This data can then be used in the future together with data from other sources for the selection of an individual therapy concept. In addition, the measurement of patient-reported outcomes (PROs), along with other clinical outcomes, is required for the assessment of therapy response. Therefore, in clinical practice, patients’ quality of life (QOL) is assessed using various outcome scales, for example, the 36-item Short Form Survey (SF-36) or the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (IBDQ).

Some mobile health applications for IBD are already being used to monitor lifestyle, environmental factors, and PROs in patients’ usual environments. A recent review summarized different electronic and mobile applications for patients with IBD and showed that publications about telemonitoring with wearable devices and smartphone apps are still relatively rare.5 Yvellez et al. conducted a 2018 study with 19 patients who used a Fitbit wearable and a mobile device application to daily monitor their QoL, sleep, and pain with a Visual Analog Sliding Scale (VASS) and for completing the Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (SIBDQ) and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index after 2 weeks. This feasibility study showed better compliance with daily VASSs and wearing the Fitbit device than with the longer periodic PRO questionnaires.6 Sossenheimer et al. (2019) provided 194 patients with a Fitbit device for collecting data on daily steps, heart rate, and sleep and a smartphone app for the completion of PROs. Because the patients with IBD made fewer steps in the week before an elevation of the biomarkers C-reactive Protein and fecal calprotectin, the authors concluded that these passive biosensor data can be used to predict elevated biomarkers of inflammation.7 Hirten et al. (2021) measured the heart-rate variability (HRV) of 15 patients with UC with the VitalPatch,8 which is a wearable patch-like biosensor worn on the left upper chest. The sensor collects data about the ECG waveform, temperature, activity, accelerometry, and respiratory rate. The study revealed an association between HRV and symptoms of inflammation and measures of stress.9 Although in particular, the Sossenheimer study gave first reliable information about the relationship between lifestyle (number of steps) and symptoms of inflammation, further research is needed to examine the value of real-life-data for the prediction of exacerbations and monitoring of therapy outcomes.

The Project GUIDE-IBD and the Features of the Health-App and Wearable

The GUIDE-IBD project10 aims to address the need for an individualized approach by seeking to identify molecular biomarkers to develop models for treatment response prediction and optimization. The subproject 3 (SP3) of GUIDE-IBD focuses on digital biomarkers.11 The highly unpredictable course of the disease can vary between patients, making it difficult to develop personalized treatment plans. The influence of individual lifestyle and the effect of the disease on QOL has not been adequately researched due to the lack of detailed, long-term observations. SP3 addresses this challenge by collecting longitudinal data directly from IBD patients over the course of 1 year by combining different mHealth technologies. With PROs collected by a smartphone app, consumer fitness tracker data (Garmin vívosmart 4), and a medical device grade movement tracker (McRoberts MoveMonitor12), the project seeks to develop models that can predict disease progression and comorbidities such as fatigue and depression. Thereby, it provides a tool for PM to make informed treatment decisions based on an individual patient’s unique disease trajectory and to prevent severe episodes before they manifest.

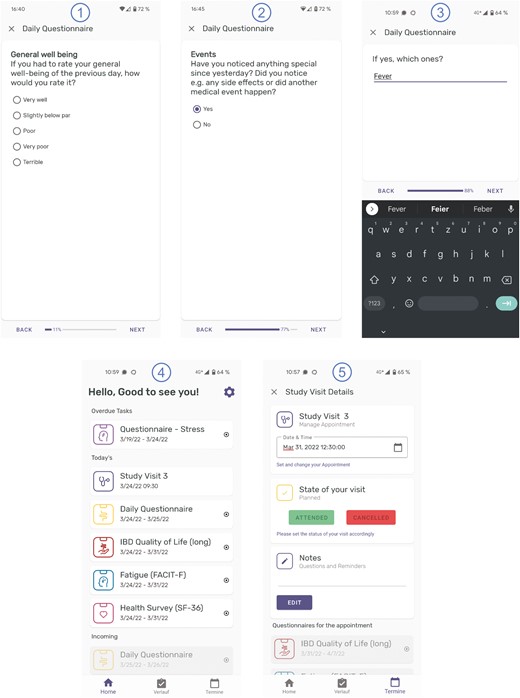

The app (Figure 1) collects PROs (QOL, health status, sleep, depression, and fatigue) during the day-to-day life of the participant by presenting different questionnaire tasks according to the study protocol. During the study, the number of questionnaires is very high. The goal is to find a subset of questions that provides the same information value to lower the patient workload. The Garmin vívosmart 4 fitness tracker captures various physiological biomarkers such as heart rate, oxygen saturation, and sleep patterns. It also tracks physical activity including steps and exercise sessions. If the data can be used to model the course of the disease, it would be a very unintrusive and a low burden method to measure the disease activity.

Five screenshots of the app: 1–3 user interfaces rendered from the questionnaire resource, 4 task list for the participant created from the plan definition and stored as service requests, 5 study visit stored as encounter.

As the fitness tracker is not a validated medical device, the McRoberts MoveMonitor was included. First to validate the accuracy of the vívosmart 4 and second to investigate the capability of its data to predict the course of the disease. The MoveMonitor is a CE (European conformity) and FDA-certified medical wearable device designed to accurately track and record physical activity, and provide detailed data on movement patterns and behavior. It is a small, lightweight sensor that can be worn on the waist using a belt clip, and it uses an accelerometer to detect movement and changes in orientation. Unfortunately, it cannot record data continuously for 1 year, like the app and the vívosmart 4. It is only possible to record data for 7 days, which is done after every study visit.

SP3 is only an additional observation study to investigate the value of the collected digital biomarkers. The data are sent directly from the phone to the research database after the questionnaires are answered or the data from the sensor (Garmin vívosmart 4) are collected. Until now, the data will not be included in treatment decisions as this could interfere with the molecular medicine part. This means, during the study, no care team or health care provider will have access to the data. However, the system can be used in the future to provide all data to the care team. This is our goal and will be the objective for our next project. The main objectives of the current project are to identify digital biomarkers and test the technical system.

Ethical and Social Issues of Self-Tracking With Wearables and mHealth-Apps

The literature contains lively discussion on the benefits and risks of a general trend toward “self-tracking” in the private and health care sector.13–17 For example, Yin et al. revealed in their review that mHealth apps like myIBDcoach or Constant Care have the potential to support patient education and, in the case of Constant Care, support individualized, self-administered treatment.14 However, the risk exists that unrealistic body and health norms may develop and thus, increase social pressure on individuals15 and feelings of guilt and shame.16 Constant information about health status can affect an individual’s productivity16 and harbors potential for addiction,15,16 and depression.15 If such side effects of using mHealth technology are not explained, users will not be able to give truly informed consent.16 Difficulties may also arise for those who cannot or do not want to use a smartphone or tracking bracelet17 or who do not have access to the internet. The paradigm shifts toward patient empowerment, driven by the use of these technologies, may also mean that some populations are unable to fulfill this responsibility because they do not have the living conditions that enable them to live healthier lives. Ultimately, this inability can open up further opportunities for stigmatization.15 Last but not least, the use of mHealth technologies raises questions about data security and the validity of the data generated.16,17 Misuse of data for unintended purposes, such as monetization of data for marketing purposes, is quite conceivable.15

However, the extent to which the GUIDE-IBD mHealth technology has similar or different benefits and risks and how this technology influences the “good life” of their users’ needs to be researched. The present study provides a first step in this direction whereby we consider, inspired by Philippa Foot, a good life not only in terms of bodily health and the absence of pain and suffering but also in terms of human flourishing. This concept includes the possibility of realizing one’s own capabilities and virtues, maintaining social relationships, experiencing contentment, joy, and pleasure, and also deep happiness and true fulfillment.18 Therefore, we are investigating the following, more comprehensive research question: How does the mobile health technology GUIDE-IBD influence patients’ lives and their perception of the body and self?

Materials and Methods

Between August, 2022 and February, 2023, we conducted 1 qualitative interview each with 10 IBD patients. These patients had been previously selected at random to take part in the GUIDE-IBD study at 2 academic IBD outpatient clinics. All patients used the GUIDE-IBD app and wearable and completed the study. However, 1 patient stopped using the app after a while and preferred to use paper and pencil instead. We contacted patients by e-mail or regular mail and informed them with a flyer about the interview substudy. Patients usually reply to this e-mail or contact us by telephone to organize an appointment for an interview. Interviews were usually conducted in the rooms of the Medical Ethics Working Group by a social scientist. Before the interview patients were informed about the aims, benefits, possible risks, and the study procedure with an information leaflet and orally by the interviewer. All participants provided written informed consent. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we conducted 2 interviews, at the request of the patients, via video chats, but 8 were face-to-face interviews. We used an interview guide (Supplementary Data S1) based on our previous literature review to ensure that all topics of interest were addressed. The interviews lasted for an average of 59 min with a range from 30 to 102 min, were recorded with an audio recorder, and transcribed verbatim. Before starting, we obtained approval from the ethics committee of Kiel University.

For data analysis, we used Interpretative Phenomenological analysis (IPA), a method that is ideally suited to studying people’s lived experience and how they make sense of this experience.19 The choice of this method seemed especially appropriate to us because we not only wanted to investigate the research question about GUIDE-IBD mentioned above, but also questions about how patients experience their body, self, and life. The results on these additional questions will be published separately elsewhere.

The use of IPA as a method for research required the analysis of data in several steps.

In Step 1, the transcribed data of each individual case were read and paraphrased in “descriptive notes.” Linguistic characteristics (“linguistic notes”) and questions or ideas about possible interpretations were recorded in “conceptual notes.”20 In practice, we conducted this work with MAXQDA, a software for qualitative data analysis, and then exported the data into an Excel sheet. In Step 2, individual short statements (“experiential statements”) were derived from these notes that succinctly represent the experience of the participants as presented in the data. These statements were summarized in a table for each case and then arranged thematically in, so-called, “personal experiential themes” (Steps 3 and 4). The resulting themes from the individual cases were then presented across cases with anchor examples into “group experiential themes” (Step 5).20

Results

Six women and 4 men took part in the interviews. Participants’ average age was 31 (range: 19–44) and they were on average 25 at the onset of their disease (range: 15–43). Seven patients suffered from CD and 3 from UC. Participants used the GUIDE-IBD app and wearable for an average of 10 months (range: 5–13) and had therefore sufficient experience with the devices (Table 1). All participants spoke German fluently and only 1 person had a migration history.

| Pseudonym . | Age . | Profession . | Disease . | Age at onset . | Use of GUIDE-IBD (months) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heather | 19 | Student | Crohn’s disease | 16 | 5 |

| Paul | 42 | Leading position not specified | Colitis ulcerosa | 40 | 9 |

| Anne | 27 | Student | Crohn’s disease | 26 | 12 |

| Sophie | 23 | Teacher | Crohn’s disease | 18 | 12 |

| Carla | 29 | Psychologist | Crohn’s disease | 20 | 12 |

| Tom | 28 | Student | Colitis ulcerosa | 15 | 6 |

| Hannah | 44 | Manager | Crohn’s disease | 43 | 13 |

| Vera | 29 | Social worker | Crohn’s disease | 16 | 12 |

| Peter | 25 | Trainee | Colitis ulcerosa | 22 | 8 |

| Daniel | 40 | Technician | Crohn’s disease | 39 | 7 |

| Pseudonym . | Age . | Profession . | Disease . | Age at onset . | Use of GUIDE-IBD (months) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heather | 19 | Student | Crohn’s disease | 16 | 5 |

| Paul | 42 | Leading position not specified | Colitis ulcerosa | 40 | 9 |

| Anne | 27 | Student | Crohn’s disease | 26 | 12 |

| Sophie | 23 | Teacher | Crohn’s disease | 18 | 12 |

| Carla | 29 | Psychologist | Crohn’s disease | 20 | 12 |

| Tom | 28 | Student | Colitis ulcerosa | 15 | 6 |

| Hannah | 44 | Manager | Crohn’s disease | 43 | 13 |

| Vera | 29 | Social worker | Crohn’s disease | 16 | 12 |

| Peter | 25 | Trainee | Colitis ulcerosa | 22 | 8 |

| Daniel | 40 | Technician | Crohn’s disease | 39 | 7 |

| Pseudonym . | Age . | Profession . | Disease . | Age at onset . | Use of GUIDE-IBD (months) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heather | 19 | Student | Crohn’s disease | 16 | 5 |

| Paul | 42 | Leading position not specified | Colitis ulcerosa | 40 | 9 |

| Anne | 27 | Student | Crohn’s disease | 26 | 12 |

| Sophie | 23 | Teacher | Crohn’s disease | 18 | 12 |

| Carla | 29 | Psychologist | Crohn’s disease | 20 | 12 |

| Tom | 28 | Student | Colitis ulcerosa | 15 | 6 |

| Hannah | 44 | Manager | Crohn’s disease | 43 | 13 |

| Vera | 29 | Social worker | Crohn’s disease | 16 | 12 |

| Peter | 25 | Trainee | Colitis ulcerosa | 22 | 8 |

| Daniel | 40 | Technician | Crohn’s disease | 39 | 7 |

| Pseudonym . | Age . | Profession . | Disease . | Age at onset . | Use of GUIDE-IBD (months) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heather | 19 | Student | Crohn’s disease | 16 | 5 |

| Paul | 42 | Leading position not specified | Colitis ulcerosa | 40 | 9 |

| Anne | 27 | Student | Crohn’s disease | 26 | 12 |

| Sophie | 23 | Teacher | Crohn’s disease | 18 | 12 |

| Carla | 29 | Psychologist | Crohn’s disease | 20 | 12 |

| Tom | 28 | Student | Colitis ulcerosa | 15 | 6 |

| Hannah | 44 | Manager | Crohn’s disease | 43 | 13 |

| Vera | 29 | Social worker | Crohn’s disease | 16 | 12 |

| Peter | 25 | Trainee | Colitis ulcerosa | 22 | 8 |

| Daniel | 40 | Technician | Crohn’s disease | 39 | 7 |

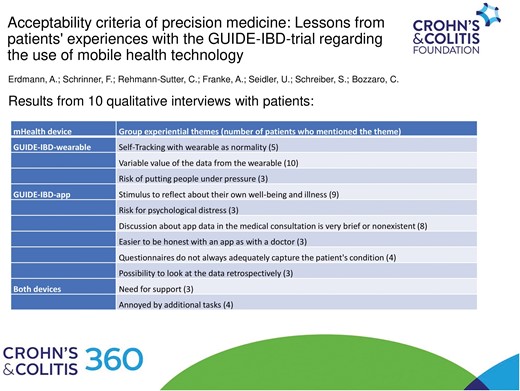

The analysis of the data resulted in 11 group experiential themes mentioned by at least 3 participants (Table 2):

| mHealth device . | Group experiential themes (number of patients who mentioned the theme) . |

|---|---|

| GUIDE-IBD wearable | Self-Tracking with wearable as normality (5) |

| Variable value of the data from the wearable (10) | |

| Risk of putting people under pressure (3) | |

| GUIDE-IBD app | Stimulus to reflect about their own well-being and illness (9) |

| Risk for psychological distress (3) | |

| Discussion about app data in the medical consultation is very brief or nonexistent (8) | |

| Easier to be honest with an app than with a doctor (3) | |

| Questionnaires do not always adequately capture the patient’s condition (4) | |

| Possibility to look at the data retrospectively (3) | |

| Both devices | Need for support (3) |

| Annoyed by additional tasks (4) |

| mHealth device . | Group experiential themes (number of patients who mentioned the theme) . |

|---|---|

| GUIDE-IBD wearable | Self-Tracking with wearable as normality (5) |

| Variable value of the data from the wearable (10) | |

| Risk of putting people under pressure (3) | |

| GUIDE-IBD app | Stimulus to reflect about their own well-being and illness (9) |

| Risk for psychological distress (3) | |

| Discussion about app data in the medical consultation is very brief or nonexistent (8) | |

| Easier to be honest with an app than with a doctor (3) | |

| Questionnaires do not always adequately capture the patient’s condition (4) | |

| Possibility to look at the data retrospectively (3) | |

| Both devices | Need for support (3) |

| Annoyed by additional tasks (4) |

| mHealth device . | Group experiential themes (number of patients who mentioned the theme) . |

|---|---|

| GUIDE-IBD wearable | Self-Tracking with wearable as normality (5) |

| Variable value of the data from the wearable (10) | |

| Risk of putting people under pressure (3) | |

| GUIDE-IBD app | Stimulus to reflect about their own well-being and illness (9) |

| Risk for psychological distress (3) | |

| Discussion about app data in the medical consultation is very brief or nonexistent (8) | |

| Easier to be honest with an app than with a doctor (3) | |

| Questionnaires do not always adequately capture the patient’s condition (4) | |

| Possibility to look at the data retrospectively (3) | |

| Both devices | Need for support (3) |

| Annoyed by additional tasks (4) |

| mHealth device . | Group experiential themes (number of patients who mentioned the theme) . |

|---|---|

| GUIDE-IBD wearable | Self-Tracking with wearable as normality (5) |

| Variable value of the data from the wearable (10) | |

| Risk of putting people under pressure (3) | |

| GUIDE-IBD app | Stimulus to reflect about their own well-being and illness (9) |

| Risk for psychological distress (3) | |

| Discussion about app data in the medical consultation is very brief or nonexistent (8) | |

| Easier to be honest with an app than with a doctor (3) | |

| Questionnaires do not always adequately capture the patient’s condition (4) | |

| Possibility to look at the data retrospectively (3) | |

| Both devices | Need for support (3) |

| Annoyed by additional tasks (4) |

In the following, we report of these themes by considering the IPA quality evaluation guide suggested by Smith which requires at least 3 interview excerpts for each theme.21 These excerpts have been translated into English for this study. We start with the themes regarding self-tracking with the GUIDE-IBD “wearable.”

Self-tracking with Wearable as Normality

Wearing the bracelet and self-tracking with it was accepted as part of their experienced normality by half of the patient group. Some patients already had experience with it through their sporting activities.

“I have it on, and well, nothing has really changed. I had such a device earlier. Because of doing sport.” (Hannah)

Most patients reported that self-tracking had no influence on their mental activity or productivity, despite the fact that the wearable sometimes gives signals.

“OK. I am aware of it. Naturally, there’s a humming here around the wristband. And it makes a bit of a racket. But that stops in about half a minute at the latest.” (Paul) “But that doesn’t distract you, does it?” (Interviewer, henceforth “I”) “No, no.” (Paul)

However, 1 patient got a rash from the wearable and another did not like wearing the bracelet at night.

“But I’m also the type of person who doesn’t like to wear body jewelry. Um, I also take my wedding ring off in the evening when I go to bed. (...) I don’t like that on me. (...) it bothers me at night.” (Paul)

Varying Value of the Data from the Wearable

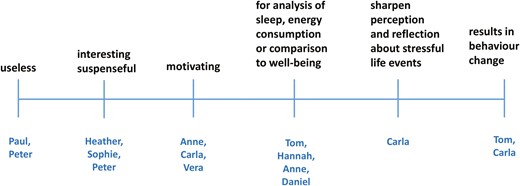

Self-tracking with the bracelet had a very different value for patients (figure 2). Although 2 patients found the data completely useless and another 3 merely interesting or suspenseful, some felt motivated by the data to continue their physical activity. Four patients used the data for the analysis of their sleep or energy consumption and compared the analysis to their own perceived well-being:

“But otherwise, it’s just kind of interesting, like when you haven’t slept well: What does the wristband say about that? When was I awake? When were my deep sleep phases? So, you can analyze a bit about what actually has happened.” (Anne)

For 2 patients, however, data collection also led to a change in behavior. For Carla, the wearable sharpens her attention to stressful situations which can trigger symptoms and reflection on these situations. As a result, this had an influence on her behavior.

“So I think, (…) when you see this data on something like the vibrating wristband, it influences you, of course. And you naturally try to avoid such situations [that cause the vibrating]. And try to create pleasing situations. And I’ve noticed for myself, (…) that relaxation is very important for me. (…) I mean that a certain downtime is important. That’s what this also showed me. And that has definitely influenced my behavior.” (Carla)

Based on the data about his insufficient deep sleep, Tom even tried to optimize his sleep with yoga, meditation, and less media consumption.

“There was something like points, (…) for example (…) 50 points, (…) in the nightly deep sleep phases, (…) but normal should be 70 to 80 so that you feel refreshed. And I tried to reach that and by doing it, I developed more ambition to do sports (…) so that I’m always optimizing my sleep, optimizing. I started watching less TV, (…) or I, (…) when in the evenings (…) I do 20 minutes of yoga and then 20 minutes of meditation.” (Tom)

In summary, our study shows that the value of the data for patients is quite different from person to person and that some patients did not consider use of the digital devices only as part of a research project, but used them to improve their condition.

Risk of Putting People Under Pressure

Despite the positive value that self-tracking with the bracelet had for some patients, they also described risks. They argued, that depending on the performance of the individual person, the data from the wearable can put people under pressure.

“So as a risk, I have to definitely think about that, well that, simply put, because I’ve just got many friends who have sport addictions and such. That this could move in that direction. In my case, I noticed quickly, that that wasn’t happening. But through this data recording [it could], especially with people who tend to be compulsive.” (Vera)

Paul mentions an important reason for that risk, namely that if a person is more active than usual, for example, on vacation, the daily goals are changed in the wearable, but then it is difficult to achieve them in everyday life.

“There are risks for people (…) after vacation, when I also do more hiking, and that, for example, raised (…) my daily goal for number of steps that increased itself. (…) Someone who so to say is guided by the wristband, they will change their life. Whether that is good or bad is something I can’t say.” (Paul)

Tom reported a burden due to an incongruence between the subjective perception of the body and objective data from the wearable. He felt better from his yoga exercises and other efforts to improve his sleep, but the deep sleep data did not show these improvements on the bracelet, which put him under stress.

“I can only say for myself that I (…) at some point reached the stage where I also understood that, ‘Hey, you’re stressing yourself.’” (…) And that was such an interplay (…) with the data recorded on the wristband. Yeah, and at some point, I told myself, ‘Hey, hey, you are more recuperated and you are doing better because you’re turning off the TV and reading and meditating (…) but the point amounts aren’t changing. So just let it be, because you actually feel better. (…) If the watch isn’t reflecting that now, then that is just how it is.’” (Tom)

The following themes now refer to the GUIDE-IBD “health app”:

Stimulus to Reflect About Their Own Well-Being and Illness

Regarding the app, most patients said that questions from the app about sleep, fatigue, physical activity, and social constraints trigger their reflection about how they actually feel.

“So, you’ve gotten to know yourself very well, and then just to know, well, how you yourself are feeling. (…) You have a different view of the perceptions.” (Sophie)

Some of them reported that the app trains their perception of symptoms and which life events or habits trigger these symptoms:

“I think that each person gains for themselves different knowledge. And also, everyone understands their illness better than before. So what are the triggers for bowel movement frequency? What triggers exhaustion? What triggers stress? (…) and then you can just consider, what…think about lifestyle. What was going on in that time?” (Carla)

In addition, Vera was convinced, that the app makes it easier to notice an improvement in symptoms.

“And it was simply beautiful to see (…) to so consciously be aware of the improvement. So I could just totally follow that when I was filling it out. So, that was then really: Surprise! OK, incredible! I can now mark another stool form” (Vera)

Risk for Psychological Distress

Three patients mentioned the risk of psychological distress because answering the questions in the app objectively demonstrates one’s own bad condition.

“I noticed that when the big, weekly questionnaires came, that it would at first bring me emotionally down. Because well, such questions about depression (…) to tenseness, anxiety disorders, sleep behavior, yes (…) So those are just things that make you clearly realize how you are really doing.” (Anne)

Daniel experienced the questions about fear of surgery as particularly burdensome but admitted that it also depended on his daily mood.

“Sometimes, it brings you a little bit more down as on other days. But that is just somehow dependent on your momentary form (…). Yes, when I then read, ‘Are you anxious that a further operation could result?’ or things like that.” (Daniel)

Peter was concerned that the data would make people feel more ill than they actually are.

“When afterwards, you see every day the details about how you are doing, you make yourself (…) also more ill than if you simply, (…) just live the day. When you always have this data situation in front of your eyes, it isn’t good.” (Peter)

Very Brief or Nonexistent Discussion of Data in the Medical Consultation

One important question for us as researchers was how the data is used in communication with health care professionals (HCPs) in the clinic. Surprisingly, most patients reported that the data is only discussed briefly or not even at all in the medical consultation.

“But the doctor I talk with doesn’t really look at it [the data] much and always asks me extra how the last 7 days were. Yes, I have the feeling that they don’t really look at it.” (Heather)

Daniel even took extra notes of the data to use in the doctor’s consultation, as he knew that the doctors did not have a look at the data.

“And so I noted it [the data] twice, I just noted everything down again.“ (Daniel)

Paul seemed a little annoyed by the fact that the data was collected twice, once with the app, and once in the doctor’s consultation.

“And I get the same questions. ‘How often did you have a bowel movement in the last days? What consistency was it?” And so on. (Paul)

Easier to Be Honest With an App Than With a Doctor

A completely unexpected result was that 3 patients reported that they could be more honest about their symptoms with an app than talking to a doctor.

“Yes, or when you’re well, more honest on the device. So, for example, I’m a patient who likes to sugarcoat things. (…) And so, I think to that end, it can also be helpful. Because when you are just, when you are filling it out alone just for yourself, you might be more honest than when you are sitting somewhere in front of a doctor. You just don’t want to be – in quotes - a burden. “(Anne)

Vera has also noticed that she sometimes gives socially desirable answers in a medical setting and therefore finds the app more comfortable.

“…because with it, I really have racked my brain more to answer the questions with complete honesty. (…) And then I don’t know, oh do I want to actually give an answer again that’s desired? It’s hard for me when I am there to have a good grip on things. (…) especially when it comes to evaluating my own body (…) and communicating needs in such a setting with doctors. That’s often very difficult for me. But that [the app] was really agreeable.” (Vera)

Daniel also apparently tries to present his condition to doctors better than it is.

“Oh well, and that is just somehow or other always such a problem because many doctors have expressed the opinion to me that: ‘Yes, actually, you are doing too well. But I am not doing well. That is just not the case. I’m just try to boost myself, OK?” (Daniel)

Questionnaires Do Not Always Adequately Capture the Patient’s Condition

Four patients reported that the items of the outcome scales in the app do not really capture their actual condition. This was the case for the scales on sleep, anxiety, sexuality, and stool form. Paul, for example, felt that his sleep disturbance was not properly recorded.

“With the theme of sleep, I never have problems falling asleep. When I lay down, I fall asleep within 10 minutes. My problem is more that I have to get up 3 times a night because I need to use the bathroom. (…) This, for example, isn’t asked about.“(Paul)

Carla thinks the anxiety scale capture generalized anxiety rather than anxiety about a specific situation, which is more the case for her.

“They were more like scary questions related to a horror movie. Like, ‘Are you terrified?’ No, I am not terrified. (…) It would be better to ask: (…) ‘Do concrete situations cause you anxiety in your daily life?’ (…) so that it goes a bit more into detail.” (Carla)

Peter reported that his interest in sexuality had extremely diminished during a phase of illness and that questions about sexuality were only asked once during the entire study period.

At the beginning, questions were asked about my sexual, I’ll call it now, performance. So, about sexual capability (…) how I assess it. But that, for example never came up again in a question. (Peter)

Peter also had difficulties selecting the correct stool form in the daily questionnaires, as this can change during the course of a day, but only 1 form per day was possible to select.

“The app asks me how my stool looked today or yesterday. And then I’m asked how often I had to go to the toilet. It would make more sense the other way around. Because if I’ve been to the toilet 2 or 3 times, for example, 1 time I had (…) it was hard as a rock, the other time it was totally liquid. This isn’t differentiated. I have to decide between hard as a rock and liquid. (…) It should be the other way around. First the number. And then you can specify for the (…) respective bowel movements what it was like.” (Peter)

Possibility to Look at the Data Retrospectively

Because the data requested in the app obviously has value for most patients, some patients would like to be able to view the data retrospectively in history in order to assess the course of the symptoms and to relate them to life events.

“And what I’d actually like (…) to see is, which wave motion (…) I mean with the answers I gave. Depicted as a diagram (…) and I could see: I was doing better in these phases. What caused that? Perhaps I didn’t have worries, or huge stress (…) I miss that I little.” (Peter)

Daniel thinks that an illustration of the data from the app would also be helpful for the physicians.

“I think it’s great that you have the entire process, the data and everything. But I think again it is a bit of a disadvantage because the doctors aren’t allowed to view this GUIDE-IBD. In my case, I think that would be very interesting.” (Daniel)

Carla believes that by assessing the course of her symptoms and how they relate to life events, she can regain some control over her condition.

“So I only have a feeling for how it was in the last few weeks. And it would be another insight for me to think about what exactly happened in these weeks. (…) But you don’t see that when the questions (…) are sent off. I would also have been interested in the topic of stool frequency, how that has changed over time. (…) It has improved, I know that. But (…) when [that happened] was perhaps also a quantum leap. (…) This I don’t know, no idea. (…) I think that you give patients back a bit of the control that they so lack over the disease.” (Carla)

Two themes refer to both the GUIDE-IBD app and the wearable. These themes are The need for support and Annoyed by additional tasks.

The Need for Support

Patients showed different abilities to use the wearable and the app. Some patients expressed various needs, partly related to the practical use of the app, but also to psychological care. The app seems to reinforce the necessity of psychological care. Anne spoke in detail about that.

“Here, I see with the app more risks with these questionnaires. Because I can just imagine that when someone isn´t in psychotherapeutic care, that this can also be very (…) burdening in the moment. When you are interrogated about your depression. Or also anxieties about the future are involved here. That this can just evoke even more negative thoughts than the ones that are really in your present situation. You then just really begin to preoccupy yourself and say, ‘Oh right, it could be that in the future, I’ll have to have an operation. Or I’ll need another artificial stoma, or, or, or. I believe there are also people who don’t begin to deal with something until they actually encounter it. And here, the app is quite predestinated. And I think, that additional support makes sense.” (Anne)

Some interview quotes indicated that patients need assistance in using the wearable or the app, for example, to fill out the number representation on a line.

“I have to use a number scale to indicate my answers about the state of my health in various areas. 100% is not allowed. Even when I am of the opinion that: I’m doing really well. 100% isn’t possible. I think that is a bit strange.” (Peter)

Additionally, Peter also had difficulties installing the correct alarm limits on the wearable, since it was already programmed to emit an alarm in case of too little physical activity.

“Then when I would just be walking a little, the wristband would suddenly vibrate. It thought I was doing a workout. (I: Hm.) I’m going to work. I’m not doing a workout.“(Peter)

In contrast, another patient, who also felt stressed by the alarms, was able to switch them off.

“Besides that. It stressed me a little (…) It really got on my nerves very quickly, so I just turned it off.” (Daniel)

Because Carla also pointed out a general need for support, it seems, that support from an e-health-nurse could be helpful for some patients as part of individualized care.

“Perhaps it would be good when at the beginning, so in the introductory phase, if someone perhaps just got in touch directly and asked, ‘So how’s it going with the app? Have you noticed anything?’ I think that would be helpful.” (Carla)

Annoyed by Additional Tasks

Several patients commented that they were annoyed either by charging the mobile phone or bracelet or by filling out the questionnaires. Paul felt that charging was an additional burden on top of his troubles with the disease.

“Well, to be honest, it bugs me.” (I: “Aha, tell me? What exactly is bugging you?”) “Yes, um, this basic maintenance of the, of the bracelet. With the charging, you know. It has to be charged every two, to three days. I’m someone who, who has a phone that will run for a week, (I: Yes.) because it annoys me to have to constantly re-charge my phone. And it is just again in, in this process where with me, I’m just somehow happy about every free minute that I have. And this [frequent recharging] is something I have to take care of additionally. (…) the illness already gets on my nerves tremendously. And now I have the tracking bracelet, so to speak. (…) And I find it more of a burden. As a temporal burden. (Paul)

Vera also found charging the bracelet and phone annoying, and she had trouble remembering to put the bracelet back on when she left the house. She also found filling out the questionnaires on her cell phone burdensome, so she asked for the option of filling them out on paper.

“Well, the recharging can be a little irritating. It was, I think, some kind of mini-USB thingy. And that’s a different kind of port than my phone has. That means I don’t have this [kind of port] on hand. Of course, I had been given a charge cable, but well, it also happened that I was recharging the wristband. Then I started doing something else and then ended up leaving home without the wristband.” (…) (I: And why did you use paper for filling it [the data] out?”) “Because doing it on the phone was totally irritating.” (Vera)

Sophie described filling out the questionnaires as “exhausting” because she often forgot the daily questionnaires and then filled them out retroactively.

“And then I had a thousand questionnaires that I had to fill out afterwards. I found that very exhausting and I often caught myself just completely forgetting about it. And then it was already Sunday and then [I was like] ’Oh God, you forgot to do questionnaires all week!’” (Sophie)

Discussion

In our study, we found 11 main themes in the reported experiences of patients with IBD with the GUIDE-IBD mHealth technology that qualify as group experiential themes. These themes could be further grouped into 3 overarching categories, which we now use to structure our discussion. We start with the benefits of the GUIDE-IBD mHealth technology followed by the risks and close with the potential for improvement.

Benefits

Tracking with the GUIDE-IBD wearable and the Guide-IBD app is of value for many patients, according to their own judgment. Although the value of the data from the wearable is judged quite differently by the patients—ranging from useless to behavior-changing—the majority of respondents had at least some interest in the data. Regarding the GUIDE-IBD app, the picture is clearer. For most patients, answering the questions in the app was a good opportunity to reflect on their own condition. The app helped some of them to perceive their symptoms and to notice what can trigger these symptoms, which enabled them to avoid such triggers. Therefore, it seems that the GUIDE-IBD mobile health technology has the potential to empower patients, at least in part, to self-manage their condition, which the researchers of the GUIDE-IBD study had ostensibly not intended with their study.10 This result shows that devices like the GUIDE-IBD app can potentially contribute to improving the “good life” of patients since the missing control and autonomy due to the unpredictable and highly individual course of their disease are a major problem. Indeed, the notion of empowerment through the use of mHealth devices is a common narrative in the context of PM.22–24 The self-management of chronic diseases serves the interest of numerous national health care strategies with a focus on PM, and mobile health technologies are a cost-efficient method to support self-management and empowerment.25 Stampe et al. pointed out that the empowerment with mHealth devices serves as a means to ensure that patients with chronic diseases comply with lifestyle changes, which today can no longer be achieved by the authoritative power of the physician.25 This raises the question of for whom the technology is more likely to serve: the patients or other relevant stakeholders, such as the mhealth industry or HCPs.

Stampe et al. focused on another problem: that during consultations with the physician the mHealth technology structures the patients’ speech around deviations from PRO data and “in doing so, it may have a silencing effect on patients’ voices.”25 This conclusion contradicts some statements of patients in our study, who said that they found it easier to enter their symptoms into the app than to tell a doctor about them. Perhaps the anonymity of the device enabled them to be more honest, which means that in some cases the data may be more valid than if collected in conversation by the doctor. In addition, the data represents the course of the symptoms over a longer period of time, which health care providers highlight as an advantage.4 These different empirical results show that the collection of PRO data with a mHealth device has advantages for both patients and HCPs. Furthermore, our results show that some patients seemed to be annoyed if they were faced with the same questions in the medical consultation they had already answered in the app. This demonstrates that patients take their engagement seriously and expect the physician to acknowledge their work. By evaluating the data before the patient’s medical consultation, the physician can take the opportunity to start a conversation directly about the meaning of the data and their implications for the individual patient.

Risks

Patients also perceived potential risks associated with the new GUIDE-IBD mobile health technology. In particular, they mentioned the risk that the data from the wearable could put people under pressure to do even more, to move more, and to sleep better. This pressure is further increased if the wearable does not record valid data, which is a necessary prerequisite for its use in the health sector. Although the Garmin tracker relatively reliably monitors the heart rate,26 there is some evidence that these sleep trackers do not record sleep accurately.27 Possibly it was precisely the inaccuracy our respondent Tom reported in the results subsection on the value of the data from the wearable. He felt refreshed from sleep, but this feeling did not correspond with the data from his sleep tracker. This incongruence of data and subjective well-being could be an indication of a lack of data validity. It is also possible that the improvement in Tom’s well-being could have other causes than sleep. In any case, the validity of the data from the wearable seems important for further investigations. It is essential to check the validity of the data from the wearable with additional devices that have already been validated, as in the GUIDE-IBD study with the McRoberts Move Monitor medical device.12 In addition, support is needed to assist patients in setting their daily goals, to avoid patients feeling pressured when, for example, they have exercised more on vacation and the daily goals have changed accordingly. It is crucial to consider with the individual patients their concept of a good life and which personal goals they would like to reach. The identification and review of individual goals ensure that the “logic of always more, better, faster,” does not end by overwhelming and eventually frustrating the patient.

Although the patients in our study were relatively young and used to digital devices, some of them experienced the related work as burdensome and time consuming. One patient even decided to stop using the app and switched to paper and pen instead. In addition, some patients showed a need for support in handling the wearable or the app. This need is likely to be even stronger in older patients28 and should be taken into account when introducing them to usual care. Patient education from an E-health nurse29 could be a solution to this challenge. Nevertheless, not all patients will likely be willing or able to use the devices, so data collection for some will still have to be done with paper and pencil. Support should also include psychological care since some patients in our study talked about the risk of psychological harm from filling out the questionnaires in the app. They mentioned the risk of feeling sicker than they actually were, or that the questions can create anxiety about a future with possible surgeries. Patients who are not undergoing psychotherapeutic treatment could possibly benefit from “personalized nursing care,” a holistic approach to care that embraces the needs of the evolving PM and includes the provision of psychosocial support.30

Potentials for Improvement

In the interviews, patients mentioned several potentials for app improvement. The first potential was related to the possibility of reflecting on the disease and related lifestyle habits or events, which was a great benefit of the app for patients. Although the app offers the possibility of revisiting questionnaires that have already been answered, some patients wished to look at the data in retrospect or a statistical summary of the data. One patient clearly described that the possibility of assessing the data retrospectively in the course of the disease could give patients a little more control over the disease, which they currently miss. Kreitmair (2022) conceptualized control as a feature of empowerment in her concept analysis and mentioned control as an important motivator for using direct-to-consumer mHealth technologies. However, Kreitmair expressed doubt about whether the technology really increases control and exemplified the failed attempt to gain control over nicotine addiction through mHealth technology.24 The extent to which the GUIDE-IBD app helps patients take control of their disease should be the subject of further research.

Another important potential for improvement concerns the adaptation of the PRO scales to the symptoms of patients with IBD. In order to capture patients’ problems more validly, some scales used in the app on anxiety and sleep need to be adapted. Sleep disturbances and fear of certain situations, for example, quiet environments, should be given stronger consideration than is currently done in the used PRO. The response to the Bristol stool scale should be able to take into account a change in stool form in a single day. For this purpose, it is only necessary to allow multiple answers for this scale on each day. Questions on sexuality could be more detailed and should be given more attention as outcome parameters. Rosenblatt and Kane (2015) revealed in their review of sex-specific issues in IBD, that women who have undergone IBD-related surgery reported impairments. The reasons why women with IBD report avoiding sexual intercourse are abdominal pain, diarrhea, and fear of fecal incontinence. Depression is a further risk factor for low sexual function.31 Because sexual health is 1 of the QOL determinants, communication about sexuality should be part of the disease management.32 PRO can support this communication.

In summary, while the use of digital devices is a central and promising tool for PM, the implementation needs to also be performed in a “personalized” way in order to achieve the benefits and lower the risks for patients.

Limitations

The participants in our study represent a relatively young and educated group. For people of advanced age, children, migrants, or people with disabilities, dealing with mHealth technology is likely to present very different challenges that we were not able to identify with in this study. Adapting the technology to the requirements of these groups is surely another milestone in the development of PM. Our study also has its limitations in the fact that we did not interview patients who declined to use mHealth technologies or withdrew from the study. The reasons for their refusal or withdrawal should also be considered when evaluating mHealth technologies in health care.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all participants of this study for their valuable contributions and insights into their lives. We would also like to thank Ekaterina Petrova for her engagement in recruiting patients for this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.B., C.R.-S., and A.E.; methodology, A.E., C.R.-S.; software, A.E.; validation, C.B., C.R.-S., and A.E.; formal analysis, A.E.; investigation, A.E.; resources, C.B.; data curation, A.E.; writing—original draft preparation, A.E., F.S.; writing—review and editing, A.E., F.S., C.B., U.S., A.F., S.S., and C.R.-S.; visualization, A.E., F.S.; supervision, C.B., U.S., A.F., S.S., and C.R.-S.; project administration, C.B.; funding acquisition, C.R.-S., A.F., S.S., U.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the German Research Foundation, grant number F381 434, and the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research, grant number 031L0188A.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

Data Availability

The data are not publicly available due to ethical reasons. The public availability of data was not part of the informed consent which we obtained from the participants.

Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Kiel University, Faculty of Medicine (protocol code D 498/22, 29.6.2022).