-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Felice S Wyndham, Karen E Park, Bird signs can be important for ecocultural conservation by highlighting key information networks in people–bird communities, Ornithological Applications, Volume 125, Issue 1, 3 February 2023, duac044, https://doi.org/10.1093/ornithapp/duac044

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The ways people think, feel, speak about, and act in and with environments are inextricably intertwined with the well-being of other living things, including birds. We report on the kinds of messages contained in 598 examples of locally-defined signs from 498 bird taxa from 169 sources and 123 ethnolinguistic groups. Using Peirce’s three sign forms: symbolic, iconic, and indexical, we analyze one aspect of human–bird interactions: that of reading bird sign for ecological and social interpretations. Understanding ecological semiotic nuance is important for translating between local, regional, and global science, and for respecting autonomous processes of local people attributing value or lack thereof to birds and their habitats. Over one-third of the signs in our sample (216; 36%) were specifically described as omens of some kind, commonly of death, illness, or something “bad”. Three modes of message delivery account for the majority of the data: predicting (60%), bringing (15%; including news, rain, luck), and indicating (15%; including seasonal change, fruit ripening, animals). Reading birds to predict weather (especially rain) was common, as was listening to and interpreting birds’ alarm calls warning of snakes or predators, and knowing that a certain bird indicates the presence of certain other animals, or of a water source. We collected 51 examples of warblish, the imitation or translation of bird sounds into non-onomatopoeic words. We argue for the amplification of ecocultural conservation (attending to histories of human–nonhuman relationships in place) to channel resources and land control to local and Indigenous managers who are immersed in relevant bird–people information networks. We discuss the importance of (1) reduction of uncertainty in local and hyper-local environments, (2) biocultural provocations in which birds fulfill important roles in human society, and (3) informational connectivity and locally-defined interspecies ethical relationships as key elements for inclusive and effective ecocultural bird conservation.

Resumen

Las formas en que las personas piensan, sienten, hablan y actúan en y con los entornos son inextricablemente entrelazadas con el bienestar de otros seres vivos, incluyendo las aves. Informamos sobre los tipos de mensajes contenidos en 598 ejemplos de signos definidos localmente de 498 taxones de aves de 169 fuentes y 123 grupos etnolingüísticos. Usando las tres formas de signos de Peirce: simbólica, icónica e indexical, analizamos un aspecto de las interacciones entre humanos y aves: la lectura de signos de aves para interpretaciones ecológicas y sociales. Comprender los matices semióticos ecológicos es importante para traducir entre la ciencia local, regional y global, y para respetar los procesos autónomos de las personas locales que atribuyen valor o falta del mismo a las aves y sus hábitats. Más de un tercio de los signos de nuestra muestra (216; 36%) se describieron específicamente como presagios de algún tipo, comúnmente de muerte, enfermedad o algo “malo”. Tres modos de entrega de los mensajes representan la mayoría de los datos: predecir (60%), traer (15%; incluye noticias, lluvia, suerte) e indicar (15%; incluye cambio estacional, maduración de frutas, animales). Leer las aves para predecir el clima (especialmente la lluvia) fue común, al igual que escuchar e interpretar los llamados de alarma de las aves advirtiendo sobre serpientes o depredadores, y saber que cierta ave indica la presencia de ciertos otros animales o de una fuente de agua. Recolectamos 51 ejemplos de “warblish”, la imitación o traducción de sonidos de aves en palabras no onomatopéyicas. Abogamos por la amplificación de la conservación ecocultural (atendiendo a las historias de las relaciones entre humanos y no humanos en el lugar) para canalizar los recursos y el control de la tierra hacia los administradores locales e indígenas que están inmersos en las redes de información relevantes entre personas y aves. Discutimos la importancia de (1) la reducción de la incertidumbre en los ambientes locales e hiper-locales, (2) las provocaciones bioculturales en las que las aves cumplen funciones importantes en la sociedad humana, y (3) la conectividad informativa y las relaciones éticas entre especies definidas localmente como elementos clave para la conservación ecocultural inclusiva y efectiva.

Lay Summary

• The ways people think, feel, speak about, and act in and with their environments are inextricably intertwined with the well-being of other living things, including birds.

• We report on the kinds of messages in 598 examples of culturally-defined signs from 498 bird taxa from 169 sources and 123 ethnolinguistic groups.

• We used Peirce’s 3 sign forms: (1) symbolic, (2) iconic, and (3) indexical, to analyze human–bird interactions. In our sample 216 of the signs (36%) were specifically described as omens of some kind, most commonly of death, illness, or something “bad”.

• Reading birds to predict weather, especially rain, was common, as was listening to and interpreting birds’ alarm calls warning of snakes or predators, or indicating food or water.

• We collected 51 examples of warblish, the imitation or translation of bird sounds into non-onomatopoeic words.

• Some key ecocultural interactions include (1) reduction of uncertainty; (2) biocultural provocations in which birds fulfill important roles in human society; (3) connectivity as key for inclusive and realistic ecocultural bird conservation.

INTRODUCTION

The ways people think, feel, speak about, and act in and with their environments are inextricably intertwined with the well-being of other living things, including birds. As global conservation bodies increasingly recognize the importance of local and Indigenous leadership and control over traditional territories for biodiversity conservation, it is helpful to initiate cross-disciplinary and inter-science dialogue about the complex information interactions involved in local environmental expertise. These include local traditional and innovative knowledge of, among other things, history, politics, environmental change, mythological and spiritual relationships, ontology, and the nature of and responsibilities to life, death, and time. Here we highlight the role of one thread among these thought lineages, which is knowledge about how bird sign can be read and interpreted. Having found that it is exceedingly common for local language communities to have an established repertoire for interpreting bird signs for both ecological (material world) and socio-spiritual (supernatural world) predictions of the near future, we consider the importance of these for what we call ecocultural conservation. We use the term “ecocultural conservation” to describe an interconnected perspective that foregrounds local information interactions and amplifies local practices, ethics, and institutions in meaningful ways. This term builds on the longstanding notion of biocultural diversity and its conservation, which emerged from the collective recognition that biodiversity and cultural diversity are inextricably linked, as stated in the Declaration of Belém during the first International Society of Ethnobiology Congress (ISE 1988). We follow Franco’s suggestion (2022:6) that an expansion of the term to “ecocultural” conservation could usefully distinguish this work from the pre-existing biophysical anthropologists’ use of the term biocultural and also recognize the importance of non-living things such as water, air, and soil in the “reciprocal and inseparable link[s] between ecology and culture”.

Local communities, national planners, and international conservation policy makers all strive to reduce uncertainty in our environments and establish ways of anticipating the imminent future so as to better plan for or mitigate extraordinary change. Here we explore how these ecological skills and processes of linguistic and sociocultural interpretation link people and birds in ways that nurture the environmental connections and responsiveness that are key to local conservation processes and crucial for outsider conservationists to recognize and engage respectfully.

In many local and Indigenous communities, particular ways of knowing have informed practices that have sustained and nurtured healthy ecosystems for millennia (Armstrong et al. 2021; IPBES 2019, Schuster et al. 2019). A great deal of mainstream ecological knowledge has its roots in traditional local innovation, including any number of domesticated foods, medicines, and material goods used by people around the world today. However, translating meaning or forms of knowing between local, regional, and international contexts can be complicated and often involves violent colonial histories and power imbalances. Local views and beliefs have often been disregarded as unscientific or irrelevant (Delgado and Silvestre 2021:20) and land dispossessions have disrupted myriad local ecological practices over past centuries. A central challenge for professional conservationists working in a western scientific tradition (referred to in this article simply as conservationists) is to become more responsive to local peoples’ needs and priorities so that effective systems of local stewardship already in place may be upheld and amplified through increased autochthony over territories. Though many have called for this shift as an imperative (IPBES 2019; Beltrán 2000), the specific details of how to integrate local meaning within global conservation awareness, priorities, and exchanges are harder to manifest. How can local (shareable) cultural values, meaning, and significance be articulated with regional and global policy and action processes in ways that are accessible to people from diverse training lineages, yet respect the informational and cultural protocols of the communities of knowledge origin?

While ethno-ornithology as a field explores a multiplicity of ways that people draw meaning from interactions with birds, here we examine one facet of meaningful local ecological dialogue that in the first author’s ethnographic experience is often considered knowledge that can, at least superficially, be shared with outsiders. We identified patterns in the ways people “read” bird behavior and vocalizations as one example of human–bird connection that illustrates how informationally and ecologically interconnected we are, and how much perceived human communication with birds matters. For example, if conservation projects in a particular region became more informed about local knowledge of arrival times of migrating birds that signal seasonal shifts, these patterns could be integrated into monitoring schedules, potentially adding new dimensions to tracking and analysis of change, as long as local communities felt their concerns and priorities are also addressed. Equally, conservationists hold a lot of data that can be of use and interest to local experts in their own work. Engaging in wider inter-science dialogue with local people who feel that they, their land rights and responsibilities, and their expertise are recognized can inject vitality at the local, regional, and perhaps even global level (Delgado Burgoa and Silvestre Rojas 2021).

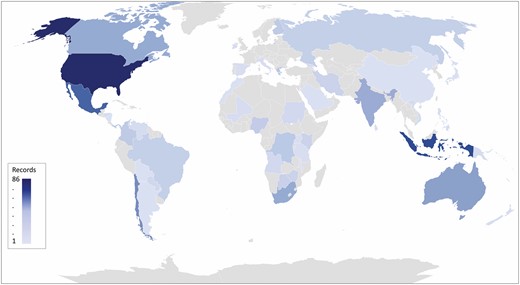

In this analysis of birds as signifiers, we report on the kinds of messages conveyed in 598 examples of culturally or locally-defined signs from 498 bird taxa across 123 ethnolinguistic groups and 56 countries (Figure 1). Our data were drawn from a literature review of 169 sources spanning ~150 years from 1864 to 2015. This dataset was previously analyzed from the perspective of which birds figure as important sign-bearers, published in the Journal of Ethnobiology (Wyndham and Park 2018). Here we focus on the content and messages in bird sign communications.

World map showing relative distribution of sources in our sample.

We used Peirce’s notion of the three overlapping modes or sign forms in play: (1) symbolic, (2) iconic, and (3) indexical (1955:104). For example, in the southern U.S., seeing a Northern Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis) can be interpreted as a sign of a visit from a spirit of a deceased relative (F. Wyndham personal observation). This is symbolic because it is arbitrary and learned. Tukano people in northern Amazonia consider the call of the large nightjar tu’ío (Caprimulgidae) to presage death, an iconic (and ideophonic) sign, as it “make[s] a noise like that of a coffin being tied” (Reichel-Dolmatoff 1971:213). When people in Australia know that the rock figs are ripe by the activity of Western Bowerbirds (Chlamydera guttata), the sign is indexical in that there is a “dynamical connection” (Peirce 1955:114) or non-arbitrary link between the two entities—the birds are there to feast on figs. Dewey (1933) framed the relation between the world and our minds as based in and reflecting on signification. Signifiers, which include symbolic, iconic, and indexical signs, are the “ground of belief” (1933:11)—the basic elements with which people can think in the sense of considering the extent to which one thing can be regarded as warranting belief in another. In this frame, indexical signs are epistemically the most straightforward, while symbolic signs rely more on learned interpretations and encultured worldviews and become more contested in environments of multi-cultural contact. Thus, outsiders to a language community tend to engage most readily with indexical signs as a potential lingua franca for ecological knowledge as they often draw on similar principles of observation, testing, hypothesis building, and ecological interpretation outsiders are familiar with. Symbolic and iconic signs are frequently stereotyped or misinterpreted by outsiders, which can harm local education systems and seed mistrust. For example, due to their own biases, some Christian missionaries in Indigenous Ayoreo territories of Paraguay in the 20th century misinterpreted the complex local mytho-ecological relationship with asonjá, the Little Nightjar (Setopagis parvula) as a supplicant-deity relation like that of their own religious practice and violently condemned and forbade traditional annual rituals between people and nightjar as being analogous to devil- or idol-worship. These ritual practices, however, were not only about people’s relation to the bird and her cultural history as a powerful, formerly human sorceress (e.g., the ritual lifted taboos protecting her nesting and fledging period), but also triggered important social calendrics including seasonal changes from itinerant trekking to more settled agricultural planting and concomitant shifts in political organization within communities (Fischermann 2005). A more nuanced understanding of the role of symbolic and iconic thinking in biology, including in western training lineages, could help all of us grasp the multiple dimensions of cultural interaction with other living things.

Most western scientists, conservationists, and epistemic pragmatists consider birds to be discrete, non-person beings wherein meaningful communication between “us” and “them” is specialized or indirect, such as that of domesticated birds, putative mutualisms as with Greater Honeyguides (Indicator indicator; Spottiswoode et al. 2016) that lead people to bees’ nests, or predator alarm calls. The notion of birds as interlocutors with a spirit world has often been unacknowledged or rejected by scientists as superstition (e.g., the ornithologist Wilson’s derision of Native American avian lore [1808–1814, quoted in Krech 2009:25]). If conservationists become more aware of the interplay of local thought and local biota, and integrate this awareness into their priorities and practice, then they will also need a basic understanding of the complexity involved in the ways people make meaning. Bird signs are rarely placed into clearly separated natural/supernatural categories in local common parlance though these categories are used here for purposes of analysis. Rather, local descriptions often reflect multiplicity, intertwining, and layering of world realities and epistemic forms between which people can move easily without much cognitive dissonance. This is especially so in the domain of omens, which, while significative, often lack clear agency, instead tapping the human faculty Beerden (2013:23) calls omen-mindedness. Omen-mindedness refers to the human propensity for seeking and finding guidance in the world around us. The selection of which things are signs has been called “the economy of signification” (Smith 1982:56 cf. p.127). We analyzed this informational economy of bird signs in terms of which signs are reported with which birds. We asked: which topics, domains, and forms are most commonly found in the signs themselves? Why might patterns emerge as they do?

Along an epistemic spectrum—from “messenger” birds thought to be sent by a supernatural being as interlocutors between worlds, through the less agent-driven perception of signs in a generally communicative universe, to naturalist observations or indicators—the task of the human reader is to evoke or just notice, then interpret the sign. Interpretation of bird sign is common—perhaps ubiquitous—among world societies. Here we describe patterns found in bird signage in a comparative sample, and discuss the implications for human cognition, ecocultural conservation, and for understanding human environments as information interactions more generally.

METHODS

Our purposive sample of published data was compiled by starting with several literature searches on “ethno-ornithology” or “ethnoornithology” using the Web of Science database, then reviewing and selecting all those that contained specific reference to birds as signifiers, which we defined as including birds perceived as harbingers, omens, teachers, indicators, or purveyors of messages. After initial analysis (Wyndham et al. 2015) we decided to increase our sample size by adding examples from the electronic Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures database (https://ehrafworldcultures.yale.edu/). The eHRAF is a searchable database of ethnographic works from around the world whose mission is to promote understanding of cultural diversity and commonality in the past and present (https://ehrafworldcultures.yale.edu/). We searched eHRAF using the terms “all cultures”; “ethnozoology”; and “bird” and extracted all texts that specifically identified birds as signs. In total we reviewed 169 sources and compiled details about 598 culturally-defined signs across 498 different taxa of birds from 123 ethnolinguistic groups (a list of groups and countries represented may be found in Table 1 in Wyndham and Park (2018 and Online Supplementary Materials; note that much of the descriptive text on our methods is reproduced from that publication, pp. 536–540). While most of the data are from ethnographic research, a few instances were reports of signs extracted from literary texts. In terms of modes of production as categorized by the eHRAF, our sample of ethnolinguistic groups was roughly equally representative of hunter-gatherers/primarily hunter-gatherers (36%); horticulturalists/other subsistence combinations (33%); and intensive agriculturalists/agro-pastoralists/ pastoralists (31%). The publication year for materials in our sample ranges from 1864 to 2015; note that publication dates are often much later than fieldwork dates. Our full dataset and source references are available at Wyndham and Park (2018)Online Supplementary Material (including links through to the full original literature sources from eHRAF).

Our sample was not representative in that we did not randomly select from all literature available to us or use HRAF’s Probability Sample Files (Ember and Ember 2016), but searched the entire eHRAF World Cultures database, supplemented with additional focused literature. Given the specialized and relatively rare nature of our subject matter, and the varied thoroughness, foci, and idiosyncrasies of diverse researchers, we wanted a purposive rather than random sample. It is by no means comprehensive of the entire corpus of published material on this topic, however. Due to the breadth of our comparative study, we were not able to provide as much ethnographic or linguistic context as we would normally require to understand particular local significances of bird communications. For example, prospective signs in any language tradition will vary in perceived reliability and seriousness but this diversity is not teased out here. The brief excerpts of defined bird signs in our sample should be understood as concise teachings that were shared with, translated, and written down by ethnographers or other interested parties but represent only a simplified glimpse of a complex and changing knowledge lineage in each language group. Each original publication may be consulted for more about the people with whom work was done, their sociohistorical contexts, and particular methods used by the knowledge recorder. Because the material we compare—bird signs—are relatively discrete cultural facts that are likely to have been faithfully recorded by ethnographers of the last 150 years, and because our sample size is large, we feel that a comparative approach is methodologically robust.

We extracted and transcribed each description of perceived bird signage into a spreadsheet for comparative analysis, leaving out unclear or uncertain data. For cases of the same bird sign found in different publications about the same culture group, we counted a single instance. The first criterion for inclusion was that signs needed to be generalized rather than one-off accounts; though there were many myths and stories that included a case of a bird talking to a person, it was included only if it represented a more general and ongoing sign relationship. We did not include avian cultural symbolism, totems, power or dream-animals, or descriptions of how people use bird calls to communicate with other people, as noted in many accounts of hunting and warfare. These are important ethnoecologically: myths, stories, sayings, and songs often encode significant ecological information about a bird’s life history, appearance, behavior, or relationships (Ibarra et al. 2013; Garteizgogeascoa et al. 2020) but are beyond the scope of the present study. Nevertheless, we recognize that cultural context is important in making particular birds more conspicuous and significant to people (Agnihotri and Si 2012:209) and there are likely to be entangled relations between broader cultural contexts and the sign aspects of birds.

When comparing sociolinguistic traditions, taxonomic identifications are often not one-to-one (e.g., a local name for a bird may correspond to several Linnaean species or vice versa), which in itself is an important framework for conservationists to learn and accommodate in database design and in the way they work with bird names and knowledge in different languages. Taxonomies that differ from Linnaean systems are not deficient or less developed. Rather, they are valuable in themselves and can be windows to understand local priorities or varying ways of interacting with environments. For many signs in our sample, the bird associated with it was undifferentiated below order or genus (e.g., “owl” instead of “Saw-whet Owl,” or “hawks” rather than “Red-tailed Hawks”). When possible, we identified each bird mentioned to its closest identifiable Linnaean taxon. We followed authors’ identifications but where possible, updated the scientific names as well as IUCN conservation status first following the BirdLife Checklist (2015; some figures may reflect this taxonomy) and subsequently HBW and BirdLife International’s Checklist (2022). In some cases, a sign was attributed to any bird whatsoever (class Aves). English common name bird groups, such as “jay” or “egret”, which are usually below the family taxonomic level but do not always map directly onto bird subfamilies, genera, or species, were particularly useful for comparing birds as this was a common level of vernacular identification. When using bird group names, results emerged at a useful level of granularity that is easily grasped in a single table or word cloud, convenient for distinguishing broad patterns and communicating results to the general public (see Table 1 for a detailed breakdown of how English Common Name bird groups arising in our analysis correspond to recognized scientific categories). We made two taxonomically awkward decisions about representing our results. Though bird groups emerged as the taxonomic clusters most congruent with vernacular uses, in the case of owls, a majority of the ethnographic reports (67%) did not differentiate which of the two owl families (typical owls or barn owls) the bird in question belonged to, much less subfamily or genus. Conversely, most of the reported signs from the bird group pheasants concerned chickens (Gallus gallus domesticus), so we identified them as such.

Scientific names for bird groups discussed in this article. Bird groups mentioned in Figures 2 and 5 and in Tables 2, 3, and 5 are listed here in alphabetic order with the nearest taxonomic level and scientific name that best fits the perceived grouping (HBW and BirdLife 2022) at the levels of family (46 occurrences); subfamily (20); genus (19); order (4); two or three families together (4); species (3); tribe (2); subspecies (1); class (1). Note that in some local taxonomies, bats are classified “as” birds or in categories that include both.

| English common name . | Taxonomic level . | Scientific name . |

|---|---|---|

| African barbets | Family | Lybiidae |

| American Goldfinches | Species | Carduelis tristis |

| New World Sparrows (formerly American Sparrows) | Family | Passerellidae |

| Asian barbets | Family | Megalaimidae |

| Auks | Family | Alcidae |

| Babblers | Families | Timaliidae and Pomatostomidae |

| Bats | Order | Chiroptera |

| Bee-eaters | Family | Meropidae |

| Birds | Class | Aves |

| Bluebirds | Genus | Sialia |

| Bowerbirds | Family | Ptilonorhynchidae |

| Caracaras | Subfamily; Tribe | Falconinae; Polyborini |

| Chachalacas | Genus | Ortalis |

| Chats | Subfamily | Icterinae |

| Chickadees | Genus | Poecile |

| Chickens | Subspecies | Gallus gallus domesticus |

| Cockatoos | Family | Cacatuidae |

| Coots | Genus | Fulica |

| Cranes | Family | Gruidae |

| Crows | Genus | Corvus |

| Cuckoos | Family | Cuculidae |

| Cuckooshrikes | Family | Campephagidae |

| Doves | Subfamily | Peristerinae |

| Drongos | Genus | Dicrurus |

| Ducks | Subfamily | Anatinae |

| Eagles | Subfamily | Accipitrinae |

| Egrets | Family | Ardeidae |

| Falcons | Genus | Falco |

| Fantails | Genus | Rhipidura |

| Finches | Subfamily | Poospizinae |

| Flowerpeckers | Family | Dicaeidae |

| Frigatebirds | Genus | Fregata |

| Geese | Genera | Anser and Branta |

| Guineafowl | Family | Numididae |

| Gulls | Subfamily | Larinae |

| Hawks | Subfamily | Accipitrinae |

| Herons | Family | Ardeidae |

| Honeyeaters | Family | Meliphagidae |

| Honeyguides | Family | Indicatoridae |

| Hoopoes | Genus | Upupa |

| Hornbills | Family | Bucerotidae |

| Hummingbirds | Family | Trochilidae |

| Ibises | Subfamily | Threskiornithinae (?) |

| Jays | Family | Corvidae |

| Kingfishers | Family | Alcedinidae |

| Larks | Family | Alaudidae |

| Loons | Genus | Gavia |

| Martins | Subfamily | Pseudochelidoninae |

| Meadowlarks | Genus | Sturnella |

| Mockingbirds | Family | Mimidae |

| Monarch flycatchers/Monarchs | Family | Monarchidae |

| New World blackbirds | Family | Icteridae |

| Nightjars | Family | Caprimulgidae |

| Nuthatches | Genus | Sitta |

| Old World flycatchers | Subfamily | Saxycolinae |

| Old World vultures | Subfamily; Tribe | Accipitrinae; Gypini |

| Old World warblers | Family | Sylviidae |

| Orioles | Families | Oriolidae and Icteridae |

| Ospreys | Species | Pandion haliaetus |

| Owls | Order | Strigiformes |

| Owlet-nightjars | Genus | Aegotheles |

| Pardalotes | Genus | Pardalotus |

| Parrots | Order | Psittaciformes |

| Partridges | Subfamily | Phasianinae |

| Pheasants | Subfamily | Phasianinae |

| Pigeons | Subfamily | Raphinae |

| Plovers | Family | Charadriidae |

| Quail | Order | Galliformes |

| Rails | Subfamily | Rallinae |

| Robins | Families | Muscicapidae, Petroicidae, and Turdidae |

| Rollers | Family | Coraciidae |

| Sandgrouse | Family | Pteroclidae |

| Sandpipers | Subfamily | Calidrinae |

| Shrikes | Family | Laniidae |

| Snipes | Subfamily | Scolopacinae |

| Sparrows | Family | Passeridae |

| Starlings | Family | Sturnidae |

| Storks | Family | Ciconiidae |

| Swallows | Subfamily | Hirundininae |

| Swifts | Family | Apodidae |

| Thick-knees | Family | Burhinidae |

| Thornbills | Subfamily | Lesbiinae |

| Thrushes | Family | Turdidae |

| Tits | Family | Paridae |

| Toucans | Family | Ramphastidae |

| Trogons | Family | Trogonidae |

| Turacos | Family | Musophagidae |

| Turkeys | Genus | Meleagris |

| Typical owls | Family | Strigidae |

| Tyrant flycatchers | Family | Tyrannidae |

| Vultures | Families | Accipitridae and Cathartidae |

| Wagtails | Genus | Motacilla |

| Waxbills | Subfamily | Estrildinae |

| Weavers | Family | Ploceidae |

| Wedgebills | Genus | Psophodes |

| Western Tanagers | Species | Piranga ludoviciana |

| Whistlers | Family | Pachycephalidae |

| Woodcreepers | Subfamily | Dendrocolaptinae |

| Woodpeckers | Family | Picidae |

| Woodswallows | Genus | Artamus |

| Wrens | Family | Troglodytidae |

| English common name . | Taxonomic level . | Scientific name . |

|---|---|---|

| African barbets | Family | Lybiidae |

| American Goldfinches | Species | Carduelis tristis |

| New World Sparrows (formerly American Sparrows) | Family | Passerellidae |

| Asian barbets | Family | Megalaimidae |

| Auks | Family | Alcidae |

| Babblers | Families | Timaliidae and Pomatostomidae |

| Bats | Order | Chiroptera |

| Bee-eaters | Family | Meropidae |

| Birds | Class | Aves |

| Bluebirds | Genus | Sialia |

| Bowerbirds | Family | Ptilonorhynchidae |

| Caracaras | Subfamily; Tribe | Falconinae; Polyborini |

| Chachalacas | Genus | Ortalis |

| Chats | Subfamily | Icterinae |

| Chickadees | Genus | Poecile |

| Chickens | Subspecies | Gallus gallus domesticus |

| Cockatoos | Family | Cacatuidae |

| Coots | Genus | Fulica |

| Cranes | Family | Gruidae |

| Crows | Genus | Corvus |

| Cuckoos | Family | Cuculidae |

| Cuckooshrikes | Family | Campephagidae |

| Doves | Subfamily | Peristerinae |

| Drongos | Genus | Dicrurus |

| Ducks | Subfamily | Anatinae |

| Eagles | Subfamily | Accipitrinae |

| Egrets | Family | Ardeidae |

| Falcons | Genus | Falco |

| Fantails | Genus | Rhipidura |

| Finches | Subfamily | Poospizinae |

| Flowerpeckers | Family | Dicaeidae |

| Frigatebirds | Genus | Fregata |

| Geese | Genera | Anser and Branta |

| Guineafowl | Family | Numididae |

| Gulls | Subfamily | Larinae |

| Hawks | Subfamily | Accipitrinae |

| Herons | Family | Ardeidae |

| Honeyeaters | Family | Meliphagidae |

| Honeyguides | Family | Indicatoridae |

| Hoopoes | Genus | Upupa |

| Hornbills | Family | Bucerotidae |

| Hummingbirds | Family | Trochilidae |

| Ibises | Subfamily | Threskiornithinae (?) |

| Jays | Family | Corvidae |

| Kingfishers | Family | Alcedinidae |

| Larks | Family | Alaudidae |

| Loons | Genus | Gavia |

| Martins | Subfamily | Pseudochelidoninae |

| Meadowlarks | Genus | Sturnella |

| Mockingbirds | Family | Mimidae |

| Monarch flycatchers/Monarchs | Family | Monarchidae |

| New World blackbirds | Family | Icteridae |

| Nightjars | Family | Caprimulgidae |

| Nuthatches | Genus | Sitta |

| Old World flycatchers | Subfamily | Saxycolinae |

| Old World vultures | Subfamily; Tribe | Accipitrinae; Gypini |

| Old World warblers | Family | Sylviidae |

| Orioles | Families | Oriolidae and Icteridae |

| Ospreys | Species | Pandion haliaetus |

| Owls | Order | Strigiformes |

| Owlet-nightjars | Genus | Aegotheles |

| Pardalotes | Genus | Pardalotus |

| Parrots | Order | Psittaciformes |

| Partridges | Subfamily | Phasianinae |

| Pheasants | Subfamily | Phasianinae |

| Pigeons | Subfamily | Raphinae |

| Plovers | Family | Charadriidae |

| Quail | Order | Galliformes |

| Rails | Subfamily | Rallinae |

| Robins | Families | Muscicapidae, Petroicidae, and Turdidae |

| Rollers | Family | Coraciidae |

| Sandgrouse | Family | Pteroclidae |

| Sandpipers | Subfamily | Calidrinae |

| Shrikes | Family | Laniidae |

| Snipes | Subfamily | Scolopacinae |

| Sparrows | Family | Passeridae |

| Starlings | Family | Sturnidae |

| Storks | Family | Ciconiidae |

| Swallows | Subfamily | Hirundininae |

| Swifts | Family | Apodidae |

| Thick-knees | Family | Burhinidae |

| Thornbills | Subfamily | Lesbiinae |

| Thrushes | Family | Turdidae |

| Tits | Family | Paridae |

| Toucans | Family | Ramphastidae |

| Trogons | Family | Trogonidae |

| Turacos | Family | Musophagidae |

| Turkeys | Genus | Meleagris |

| Typical owls | Family | Strigidae |

| Tyrant flycatchers | Family | Tyrannidae |

| Vultures | Families | Accipitridae and Cathartidae |

| Wagtails | Genus | Motacilla |

| Waxbills | Subfamily | Estrildinae |

| Weavers | Family | Ploceidae |

| Wedgebills | Genus | Psophodes |

| Western Tanagers | Species | Piranga ludoviciana |

| Whistlers | Family | Pachycephalidae |

| Woodcreepers | Subfamily | Dendrocolaptinae |

| Woodpeckers | Family | Picidae |

| Woodswallows | Genus | Artamus |

| Wrens | Family | Troglodytidae |

Scientific names for bird groups discussed in this article. Bird groups mentioned in Figures 2 and 5 and in Tables 2, 3, and 5 are listed here in alphabetic order with the nearest taxonomic level and scientific name that best fits the perceived grouping (HBW and BirdLife 2022) at the levels of family (46 occurrences); subfamily (20); genus (19); order (4); two or three families together (4); species (3); tribe (2); subspecies (1); class (1). Note that in some local taxonomies, bats are classified “as” birds or in categories that include both.

| English common name . | Taxonomic level . | Scientific name . |

|---|---|---|

| African barbets | Family | Lybiidae |

| American Goldfinches | Species | Carduelis tristis |

| New World Sparrows (formerly American Sparrows) | Family | Passerellidae |

| Asian barbets | Family | Megalaimidae |

| Auks | Family | Alcidae |

| Babblers | Families | Timaliidae and Pomatostomidae |

| Bats | Order | Chiroptera |

| Bee-eaters | Family | Meropidae |

| Birds | Class | Aves |

| Bluebirds | Genus | Sialia |

| Bowerbirds | Family | Ptilonorhynchidae |

| Caracaras | Subfamily; Tribe | Falconinae; Polyborini |

| Chachalacas | Genus | Ortalis |

| Chats | Subfamily | Icterinae |

| Chickadees | Genus | Poecile |

| Chickens | Subspecies | Gallus gallus domesticus |

| Cockatoos | Family | Cacatuidae |

| Coots | Genus | Fulica |

| Cranes | Family | Gruidae |

| Crows | Genus | Corvus |

| Cuckoos | Family | Cuculidae |

| Cuckooshrikes | Family | Campephagidae |

| Doves | Subfamily | Peristerinae |

| Drongos | Genus | Dicrurus |

| Ducks | Subfamily | Anatinae |

| Eagles | Subfamily | Accipitrinae |

| Egrets | Family | Ardeidae |

| Falcons | Genus | Falco |

| Fantails | Genus | Rhipidura |

| Finches | Subfamily | Poospizinae |

| Flowerpeckers | Family | Dicaeidae |

| Frigatebirds | Genus | Fregata |

| Geese | Genera | Anser and Branta |

| Guineafowl | Family | Numididae |

| Gulls | Subfamily | Larinae |

| Hawks | Subfamily | Accipitrinae |

| Herons | Family | Ardeidae |

| Honeyeaters | Family | Meliphagidae |

| Honeyguides | Family | Indicatoridae |

| Hoopoes | Genus | Upupa |

| Hornbills | Family | Bucerotidae |

| Hummingbirds | Family | Trochilidae |

| Ibises | Subfamily | Threskiornithinae (?) |

| Jays | Family | Corvidae |

| Kingfishers | Family | Alcedinidae |

| Larks | Family | Alaudidae |

| Loons | Genus | Gavia |

| Martins | Subfamily | Pseudochelidoninae |

| Meadowlarks | Genus | Sturnella |

| Mockingbirds | Family | Mimidae |

| Monarch flycatchers/Monarchs | Family | Monarchidae |

| New World blackbirds | Family | Icteridae |

| Nightjars | Family | Caprimulgidae |

| Nuthatches | Genus | Sitta |

| Old World flycatchers | Subfamily | Saxycolinae |

| Old World vultures | Subfamily; Tribe | Accipitrinae; Gypini |

| Old World warblers | Family | Sylviidae |

| Orioles | Families | Oriolidae and Icteridae |

| Ospreys | Species | Pandion haliaetus |

| Owls | Order | Strigiformes |

| Owlet-nightjars | Genus | Aegotheles |

| Pardalotes | Genus | Pardalotus |

| Parrots | Order | Psittaciformes |

| Partridges | Subfamily | Phasianinae |

| Pheasants | Subfamily | Phasianinae |

| Pigeons | Subfamily | Raphinae |

| Plovers | Family | Charadriidae |

| Quail | Order | Galliformes |

| Rails | Subfamily | Rallinae |

| Robins | Families | Muscicapidae, Petroicidae, and Turdidae |

| Rollers | Family | Coraciidae |

| Sandgrouse | Family | Pteroclidae |

| Sandpipers | Subfamily | Calidrinae |

| Shrikes | Family | Laniidae |

| Snipes | Subfamily | Scolopacinae |

| Sparrows | Family | Passeridae |

| Starlings | Family | Sturnidae |

| Storks | Family | Ciconiidae |

| Swallows | Subfamily | Hirundininae |

| Swifts | Family | Apodidae |

| Thick-knees | Family | Burhinidae |

| Thornbills | Subfamily | Lesbiinae |

| Thrushes | Family | Turdidae |

| Tits | Family | Paridae |

| Toucans | Family | Ramphastidae |

| Trogons | Family | Trogonidae |

| Turacos | Family | Musophagidae |

| Turkeys | Genus | Meleagris |

| Typical owls | Family | Strigidae |

| Tyrant flycatchers | Family | Tyrannidae |

| Vultures | Families | Accipitridae and Cathartidae |

| Wagtails | Genus | Motacilla |

| Waxbills | Subfamily | Estrildinae |

| Weavers | Family | Ploceidae |

| Wedgebills | Genus | Psophodes |

| Western Tanagers | Species | Piranga ludoviciana |

| Whistlers | Family | Pachycephalidae |

| Woodcreepers | Subfamily | Dendrocolaptinae |

| Woodpeckers | Family | Picidae |

| Woodswallows | Genus | Artamus |

| Wrens | Family | Troglodytidae |

| English common name . | Taxonomic level . | Scientific name . |

|---|---|---|

| African barbets | Family | Lybiidae |

| American Goldfinches | Species | Carduelis tristis |

| New World Sparrows (formerly American Sparrows) | Family | Passerellidae |

| Asian barbets | Family | Megalaimidae |

| Auks | Family | Alcidae |

| Babblers | Families | Timaliidae and Pomatostomidae |

| Bats | Order | Chiroptera |

| Bee-eaters | Family | Meropidae |

| Birds | Class | Aves |

| Bluebirds | Genus | Sialia |

| Bowerbirds | Family | Ptilonorhynchidae |

| Caracaras | Subfamily; Tribe | Falconinae; Polyborini |

| Chachalacas | Genus | Ortalis |

| Chats | Subfamily | Icterinae |

| Chickadees | Genus | Poecile |

| Chickens | Subspecies | Gallus gallus domesticus |

| Cockatoos | Family | Cacatuidae |

| Coots | Genus | Fulica |

| Cranes | Family | Gruidae |

| Crows | Genus | Corvus |

| Cuckoos | Family | Cuculidae |

| Cuckooshrikes | Family | Campephagidae |

| Doves | Subfamily | Peristerinae |

| Drongos | Genus | Dicrurus |

| Ducks | Subfamily | Anatinae |

| Eagles | Subfamily | Accipitrinae |

| Egrets | Family | Ardeidae |

| Falcons | Genus | Falco |

| Fantails | Genus | Rhipidura |

| Finches | Subfamily | Poospizinae |

| Flowerpeckers | Family | Dicaeidae |

| Frigatebirds | Genus | Fregata |

| Geese | Genera | Anser and Branta |

| Guineafowl | Family | Numididae |

| Gulls | Subfamily | Larinae |

| Hawks | Subfamily | Accipitrinae |

| Herons | Family | Ardeidae |

| Honeyeaters | Family | Meliphagidae |

| Honeyguides | Family | Indicatoridae |

| Hoopoes | Genus | Upupa |

| Hornbills | Family | Bucerotidae |

| Hummingbirds | Family | Trochilidae |

| Ibises | Subfamily | Threskiornithinae (?) |

| Jays | Family | Corvidae |

| Kingfishers | Family | Alcedinidae |

| Larks | Family | Alaudidae |

| Loons | Genus | Gavia |

| Martins | Subfamily | Pseudochelidoninae |

| Meadowlarks | Genus | Sturnella |

| Mockingbirds | Family | Mimidae |

| Monarch flycatchers/Monarchs | Family | Monarchidae |

| New World blackbirds | Family | Icteridae |

| Nightjars | Family | Caprimulgidae |

| Nuthatches | Genus | Sitta |

| Old World flycatchers | Subfamily | Saxycolinae |

| Old World vultures | Subfamily; Tribe | Accipitrinae; Gypini |

| Old World warblers | Family | Sylviidae |

| Orioles | Families | Oriolidae and Icteridae |

| Ospreys | Species | Pandion haliaetus |

| Owls | Order | Strigiformes |

| Owlet-nightjars | Genus | Aegotheles |

| Pardalotes | Genus | Pardalotus |

| Parrots | Order | Psittaciformes |

| Partridges | Subfamily | Phasianinae |

| Pheasants | Subfamily | Phasianinae |

| Pigeons | Subfamily | Raphinae |

| Plovers | Family | Charadriidae |

| Quail | Order | Galliformes |

| Rails | Subfamily | Rallinae |

| Robins | Families | Muscicapidae, Petroicidae, and Turdidae |

| Rollers | Family | Coraciidae |

| Sandgrouse | Family | Pteroclidae |

| Sandpipers | Subfamily | Calidrinae |

| Shrikes | Family | Laniidae |

| Snipes | Subfamily | Scolopacinae |

| Sparrows | Family | Passeridae |

| Starlings | Family | Sturnidae |

| Storks | Family | Ciconiidae |

| Swallows | Subfamily | Hirundininae |

| Swifts | Family | Apodidae |

| Thick-knees | Family | Burhinidae |

| Thornbills | Subfamily | Lesbiinae |

| Thrushes | Family | Turdidae |

| Tits | Family | Paridae |

| Toucans | Family | Ramphastidae |

| Trogons | Family | Trogonidae |

| Turacos | Family | Musophagidae |

| Turkeys | Genus | Meleagris |

| Typical owls | Family | Strigidae |

| Tyrant flycatchers | Family | Tyrannidae |

| Vultures | Families | Accipitridae and Cathartidae |

| Wagtails | Genus | Motacilla |

| Waxbills | Subfamily | Estrildinae |

| Weavers | Family | Ploceidae |

| Wedgebills | Genus | Psophodes |

| Western Tanagers | Species | Piranga ludoviciana |

| Whistlers | Family | Pachycephalidae |

| Woodcreepers | Subfamily | Dendrocolaptinae |

| Woodpeckers | Family | Picidae |

| Woodswallows | Genus | Artamus |

| Wrens | Family | Troglodytidae |

We coded all data as to its core sign or communication, the means of delivery (voice, behavior, physical presence, or extispicy), and whether we thought, judging from the context of the recorded meaning, the communication was emically “supernatural”, defined as explicitly stated agency from “other worlds” or supernatural beings, “ecological” (decipherable, non-arbitrary, ecosystemic knowledge such as meteorology, biogeography, ethology), both, or “other/ don’t know.” We analyzed these data in terms of kinds of birds (see Wyndham and Park 2018) and kinds of messages. Here we share the results of our analysis of the latter, on the range of topics communicated in messages recognized by local people about the birds in their environments, and more generally, the emergent themes and patterns in the cultural expressions of birds as signs.

RESULTS

Kinds of Birds

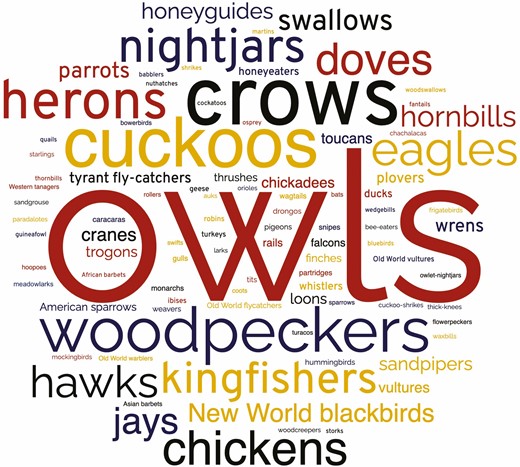

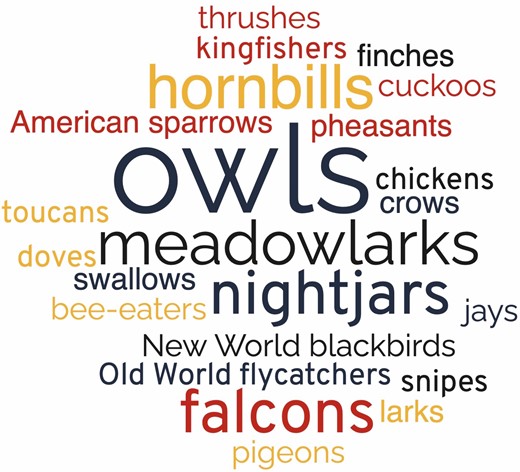

The copious results of our overall study were divided into two sections for ease of publication. The first part, a full analysis of which birds were seen as sign-bearers is available in Wyndham and Park (2018). Figure 2 provides a brief visual summary of the key results of that publication, so as to contextualize the results of the present study.

Birds that tell people things, depicted in size order of proportional occurrence. To privilege the most common vernacular taxonomic identifications, bird group names are used mostly at subfamily level (with some at genus or family level) except that chickens are identified at the subspecies level rather than their bird group name of pheasants; and typical owls and barn owls are grouped here at the order level, though they are different families, because identification was most commonly just “owl” with no further distinction. Note that this gives the owls category even more prominence than it already has.

We found that overall the most reported sign-bearers were owls, crows, cuckoos, woodpeckers, herons, eagles, nightjars, and chickens (see Table 1 for scientific categories corresponding to these bird groups). 92% of the 247 birds identified to species level were reported as Least Concern by the IUCN with respect to conservation priority (Wyndham and Park 2018:542).

Kinds of Signs

The ways researchers wrote about the cultures of bird communication in English tended to a predictable range of descriptors including birds as omens, harbingers, forecasters, signs, mediumistic messengers, teachers, and bringers of things (such as rain). Almost all of our sources were written by outsider researchers in the communities studied who described signs and their meanings in English and thus in culturally altered terms. Because of this we often missed the nuance and conceptual diversity attending these descriptors that we would otherwise have from deep- or auto-ethnographies using original languages.

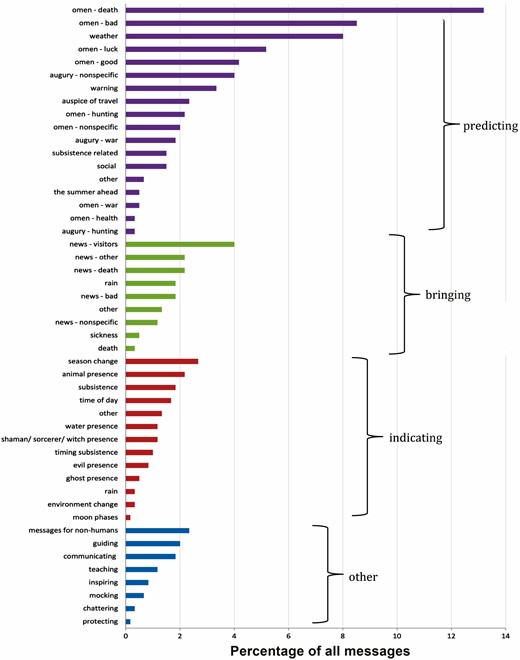

Worldwide, omens are reported as the most common category of sign people perceive in birds. Of 598 sign descriptions we collected, over a third (216; 36%) were specifically described as omens of some kind, most commonly of death, illness, or just something “bad” (Figure 3).

Proportions of all bird signs that we categorized as predicting (60%), bringing (15%), indicating (15%), and other (10%). Within each overarching category, the kinds of messages brought by birds are listed using terminology found in the literature.

In our analysis we identified and named 3 main groupings for modes of signification that account for the majority of the data: predicting (60%), bringing (15%), and indicating (15%). Many instances do not fall neatly into these categories but we tried to follow the context and vocabulary of the original source so as to tease out the nuance in how people think about the future with bird sign. Other less common modes (10% combined) include birds communicating with other animals, guiding people in the landscape (commonly to find honey), functioning as a medium for supernatural entities, teaching, inspiring, chattering, mocking, and protecting (Figure 3). “Predicting” (any prospection about the near or far future, both evoked and received) was by far the most common and includes all anticipation through omens, luck signs, weather prognostications, warnings, and augury/divination. “Bringing” includes birds carrying information about something that has already occurred elsewhere in space, mainly news (news of visitors on their way, bad news, news of a death, other) and bringing or causing events such as rain, sickness, or death. This latter sense of “bringing” overlaps with “predicting” but differs subtly in that the bird is almost always identified as having agency, rather than merely being an object co-incidentally linked to the predicted event. “Indicating” is used here as pointing out something that is already present or is currently happening, such as seasonal change, the presence of other animals, water, sorcerers/ghosts/evil beings, time of day, and food-related information (e.g., when certain foods are ready to eat). It is the simplest indexical sign, and the one that most closely maps onto western ecological understandings. All these birds’ messages are primarily related to the immediate or near future (i.e. most of the prognostications should come to pass within a few days or weeks).

Content of messages.

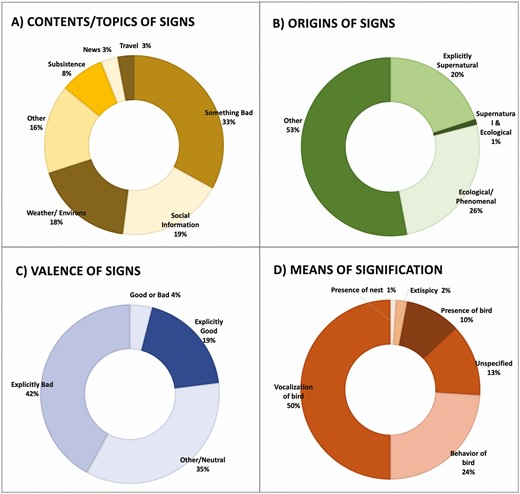

The most common type of content in bird messages was “something bad”, followed by social information and the weather (Figure 4A).

The what, whence, why, and how of bird signs. (A) Seven overarching categories by which message content can be grouped: “Something Bad” (here including all the death signs, assuming – perhaps incorrectly—that death is not usually considered a neutral or good event) (33%); “Social Information” (19%); “Weather/ Environmental” (18%); “Other” (16%); “Subsistence” related (8%); “News” and “Travel” (3% each). (B) A little less than half of all signs were categorizable as primarily ecological or phenomenal (26%) or explicitly supernatural in origin (20%), with both supernatural and ecological (S&E; 1%) falling into both categories (see Table 5 for a more nuanced portrayal). The overall majority were of “other/unknown” origin, which includes omens, auguries, and signs of luck. (C) The most common valence of a sign was explicitly bad; second-most common was neutral/other. Good signs here include explicitly marked as good plus indicators of assumed beneficial resources such as game, ripe fruit, or water. The “Good or Bad” category includes signs for which interpretation could go either way depending on specific circumstances. (D) Of the means by which signs are conveyed, vocalizations account for half and behavior for a quarter of all signs.

In analyzing these data, we categorized the attributed origins or agents of signs as “supernatural” (21%; Table 2), “ecological” (27%; Table 3), or, in the absence of explicit attribution, as “other” (53%) (Figure 4B). A little under half (46%) of all the bird signs had a “bad” or “warning” message for the recipient; 23% brought an explicitly good auspice, and 35% were not specified or of neutral valence (Figure 4C). Vocalization (Figure 4D) was the most common sign vehicle, followed by bird behavior, and bodily presence. Finding a nest as a sign was a minority report (1%), as was divining with bird innards (extispicy) or eggs (ooscopy) (2% combined).

A summary of bird signs in our sample demonstrating the types of signs that we categorized as being of supernatural origin and the bird groups associated with them. Percentages are out of total signs categorized as supernatural in origin (135).

| Message type . | Instances (%) . | Bird-as-sign-vehicles (bird group) . |

|---|---|---|

| Bringing news (news, bad news, death, from the spirit world, bad luck, ghosts, pregnancy, sex of a baby, visitors) | 24 (18%) | Owls (10), crows (3), cuckoo-shrikes (2), hawks (2), tyrant-flycatchers (2), woodpeckers, toucans, jays, nightjars, unspecified bird |

| Death omen | 20 (15%) | Owls (5), unspecified birds (4), crows (2), woodpeckers, cuckoo-shrikes, shrikes, nightjars, falcons, wrens, whistler, cockatoos, bats |

| Augury (augury, augury of war) | 16 (12%) | Chickens (3), woodpeckers (3), trogons (2), eagles, jays, hawks, kingfishers, new world blackbirds, old world flycatchers, ducks, unspecified bird |

| Indicating (sorcerer presence, ghost presence, evil presence, rain, shaman presence, animals, women’s menses) | 16 (12%) | Owls (9), wrens (2), kingfishers (2), parrots, drongos, herons |

| Bad omen (bad omen, bad luck, bad hunting, bad travel) | 13 (10%) | Crows (3), unspecified bird (2), old world warblers (2), drongos, auks, kingfishers, vultures, owls, nightjars |

| Communicating (with spirit world, agents of shamans, agents of sorcerers) | 11 (8%) | Owls (2), eagles (2), caracara, cuckoos, toucans, new world blackbirds, nightjars, ibises, thrushes |

| Bringing (rain, death, dry after flood, good luck, power, punishment, ripeness to fruit, sickness) | 10 (7%) | Owls (2), eagles (2), unspecified birds (2), crows, coots, mockingbirds, doves |

| Warning (evil beings, danger, something bad) | 6 (4%) | Owlet-nightjars, parrots, flowerpeckers, cuckoos, woodpeckers, toucans |

| Good omen (good omen, good hunting, good luck, good traveling) | 5 (4%) | Eagles (2), unspecified bird (2), old world warblers |

| Predicting (weather, good harvest) | 3 (2%) | American sparrows, geese, woodpeckers |

| Omen (nonspecific, hunting outcome) | 3 (2%) | Eagles, herons, quails |

| Teaching | 3 (2%) | Herons, nightjars, eagles |

| Inspiring (laziness, love) | 3 (2%) | Cuckoos, toucans, doves |

| Messages for non-humans (teaching, warning) | 2 (2%) | Unspecified birds (2) |

| Message type . | Instances (%) . | Bird-as-sign-vehicles (bird group) . |

|---|---|---|

| Bringing news (news, bad news, death, from the spirit world, bad luck, ghosts, pregnancy, sex of a baby, visitors) | 24 (18%) | Owls (10), crows (3), cuckoo-shrikes (2), hawks (2), tyrant-flycatchers (2), woodpeckers, toucans, jays, nightjars, unspecified bird |

| Death omen | 20 (15%) | Owls (5), unspecified birds (4), crows (2), woodpeckers, cuckoo-shrikes, shrikes, nightjars, falcons, wrens, whistler, cockatoos, bats |

| Augury (augury, augury of war) | 16 (12%) | Chickens (3), woodpeckers (3), trogons (2), eagles, jays, hawks, kingfishers, new world blackbirds, old world flycatchers, ducks, unspecified bird |

| Indicating (sorcerer presence, ghost presence, evil presence, rain, shaman presence, animals, women’s menses) | 16 (12%) | Owls (9), wrens (2), kingfishers (2), parrots, drongos, herons |

| Bad omen (bad omen, bad luck, bad hunting, bad travel) | 13 (10%) | Crows (3), unspecified bird (2), old world warblers (2), drongos, auks, kingfishers, vultures, owls, nightjars |

| Communicating (with spirit world, agents of shamans, agents of sorcerers) | 11 (8%) | Owls (2), eagles (2), caracara, cuckoos, toucans, new world blackbirds, nightjars, ibises, thrushes |

| Bringing (rain, death, dry after flood, good luck, power, punishment, ripeness to fruit, sickness) | 10 (7%) | Owls (2), eagles (2), unspecified birds (2), crows, coots, mockingbirds, doves |

| Warning (evil beings, danger, something bad) | 6 (4%) | Owlet-nightjars, parrots, flowerpeckers, cuckoos, woodpeckers, toucans |

| Good omen (good omen, good hunting, good luck, good traveling) | 5 (4%) | Eagles (2), unspecified bird (2), old world warblers |

| Predicting (weather, good harvest) | 3 (2%) | American sparrows, geese, woodpeckers |

| Omen (nonspecific, hunting outcome) | 3 (2%) | Eagles, herons, quails |

| Teaching | 3 (2%) | Herons, nightjars, eagles |

| Inspiring (laziness, love) | 3 (2%) | Cuckoos, toucans, doves |

| Messages for non-humans (teaching, warning) | 2 (2%) | Unspecified birds (2) |

A summary of bird signs in our sample demonstrating the types of signs that we categorized as being of supernatural origin and the bird groups associated with them. Percentages are out of total signs categorized as supernatural in origin (135).

| Message type . | Instances (%) . | Bird-as-sign-vehicles (bird group) . |

|---|---|---|

| Bringing news (news, bad news, death, from the spirit world, bad luck, ghosts, pregnancy, sex of a baby, visitors) | 24 (18%) | Owls (10), crows (3), cuckoo-shrikes (2), hawks (2), tyrant-flycatchers (2), woodpeckers, toucans, jays, nightjars, unspecified bird |

| Death omen | 20 (15%) | Owls (5), unspecified birds (4), crows (2), woodpeckers, cuckoo-shrikes, shrikes, nightjars, falcons, wrens, whistler, cockatoos, bats |

| Augury (augury, augury of war) | 16 (12%) | Chickens (3), woodpeckers (3), trogons (2), eagles, jays, hawks, kingfishers, new world blackbirds, old world flycatchers, ducks, unspecified bird |

| Indicating (sorcerer presence, ghost presence, evil presence, rain, shaman presence, animals, women’s menses) | 16 (12%) | Owls (9), wrens (2), kingfishers (2), parrots, drongos, herons |

| Bad omen (bad omen, bad luck, bad hunting, bad travel) | 13 (10%) | Crows (3), unspecified bird (2), old world warblers (2), drongos, auks, kingfishers, vultures, owls, nightjars |

| Communicating (with spirit world, agents of shamans, agents of sorcerers) | 11 (8%) | Owls (2), eagles (2), caracara, cuckoos, toucans, new world blackbirds, nightjars, ibises, thrushes |

| Bringing (rain, death, dry after flood, good luck, power, punishment, ripeness to fruit, sickness) | 10 (7%) | Owls (2), eagles (2), unspecified birds (2), crows, coots, mockingbirds, doves |

| Warning (evil beings, danger, something bad) | 6 (4%) | Owlet-nightjars, parrots, flowerpeckers, cuckoos, woodpeckers, toucans |

| Good omen (good omen, good hunting, good luck, good traveling) | 5 (4%) | Eagles (2), unspecified bird (2), old world warblers |

| Predicting (weather, good harvest) | 3 (2%) | American sparrows, geese, woodpeckers |

| Omen (nonspecific, hunting outcome) | 3 (2%) | Eagles, herons, quails |

| Teaching | 3 (2%) | Herons, nightjars, eagles |

| Inspiring (laziness, love) | 3 (2%) | Cuckoos, toucans, doves |

| Messages for non-humans (teaching, warning) | 2 (2%) | Unspecified birds (2) |

| Message type . | Instances (%) . | Bird-as-sign-vehicles (bird group) . |

|---|---|---|

| Bringing news (news, bad news, death, from the spirit world, bad luck, ghosts, pregnancy, sex of a baby, visitors) | 24 (18%) | Owls (10), crows (3), cuckoo-shrikes (2), hawks (2), tyrant-flycatchers (2), woodpeckers, toucans, jays, nightjars, unspecified bird |

| Death omen | 20 (15%) | Owls (5), unspecified birds (4), crows (2), woodpeckers, cuckoo-shrikes, shrikes, nightjars, falcons, wrens, whistler, cockatoos, bats |

| Augury (augury, augury of war) | 16 (12%) | Chickens (3), woodpeckers (3), trogons (2), eagles, jays, hawks, kingfishers, new world blackbirds, old world flycatchers, ducks, unspecified bird |

| Indicating (sorcerer presence, ghost presence, evil presence, rain, shaman presence, animals, women’s menses) | 16 (12%) | Owls (9), wrens (2), kingfishers (2), parrots, drongos, herons |

| Bad omen (bad omen, bad luck, bad hunting, bad travel) | 13 (10%) | Crows (3), unspecified bird (2), old world warblers (2), drongos, auks, kingfishers, vultures, owls, nightjars |

| Communicating (with spirit world, agents of shamans, agents of sorcerers) | 11 (8%) | Owls (2), eagles (2), caracara, cuckoos, toucans, new world blackbirds, nightjars, ibises, thrushes |

| Bringing (rain, death, dry after flood, good luck, power, punishment, ripeness to fruit, sickness) | 10 (7%) | Owls (2), eagles (2), unspecified birds (2), crows, coots, mockingbirds, doves |

| Warning (evil beings, danger, something bad) | 6 (4%) | Owlet-nightjars, parrots, flowerpeckers, cuckoos, woodpeckers, toucans |

| Good omen (good omen, good hunting, good luck, good traveling) | 5 (4%) | Eagles (2), unspecified bird (2), old world warblers |

| Predicting (weather, good harvest) | 3 (2%) | American sparrows, geese, woodpeckers |

| Omen (nonspecific, hunting outcome) | 3 (2%) | Eagles, herons, quails |

| Teaching | 3 (2%) | Herons, nightjars, eagles |

| Inspiring (laziness, love) | 3 (2%) | Cuckoos, toucans, doves |

| Messages for non-humans (teaching, warning) | 2 (2%) | Unspecified birds (2) |

Types of signs that were categorized as informationally ecological and the bird groups associated with them. Percentages are out of total ecological signs (155). Owls are listed by order.

| Message type . | Instances (%) . | Bird-as-sign-vehicle (bird group) . |

|---|---|---|

| Signaling rain (or snow) | 29 (18%) | Swallows (4), woodpeckers (3), plovers (2), American sparrows (2), hornbills, caracaras, wrens, herons, cranes, swifts, martins, loons, chachalacas, cuckoos, crows, pheasants, tits, jays, eagles, sandpipers, hawks, unspecified bird. |

| Indicating food (ripe wild foods, honey, time to harvest crops, likelihood of good harvest, presence of prey animals) | 29 (18%) | Honeyguides (6), unspecified bird (6), doves (3), cuckoos (2), honeyeaters, woodpeckers, bowerbirds, woodswallows, whistlers, thornbills, rails, new world blackbirds, bee-eaters, finches, geese, jays |

| Predicting weather (storms, clear, wind, drought) | 20 (13%) | Crows (2), herons (2), hawks (2), cuckoos (2), gulls (2), eagles, larks, turkeys, frigatebirds, loons, caracaras, owls, sandpipers, ducks, unspecified bird. |

| Indicating seasonal change (spring, summer, winter, rainy season, dry season) | 18 (11%) | Nightjars (2), sandpipers, meadowlark, American sparrows, trogons, hornbills, cuckoos, robins, rails, rollers, tits, typical owls, kingfishers, ducks, thrushes, snipes, unspecified bird. |

| Indicating the presence of animals | 16 (10%) | Unspecified bird (3), hawks (2), egrets, starlings, babblers, nightjars, honeyeaters, falcons, woodcreepers, eagles, jays, toucans, kingfishers |

| Other (including: indicating camps nearby, moon phases, other people ahead, women’s menses, teaching) | 16 (10%) | Unspecified bird (4), monarchs, crows, nightjars, meadowlark, plovers, chickadees, hummingbirds, loons, jays, weavers, new world blackbirds, kingfishers |

| Indicating time of day | 10 (6%) | Unspecified bird (4), hornbills, honeyeaters, new world blackbirds, pheasants, bluebirds, Asian barbets |

| Warnings or other messages for non-humans | 8 (5%) | Hawks, honeyeaters, parrots, turkeys, turacos, hornbills, African barbets, chats |

| Indicating water | 7 (4%) | Egrets, starlings, waxbills, sandgrouse, guineafowl, parrots, doves |

| Bringing news of visitors to come | 4 (3%) | Cuckoos, whistlers, fantails, unspecified bird. |

| Message type . | Instances (%) . | Bird-as-sign-vehicle (bird group) . |

|---|---|---|

| Signaling rain (or snow) | 29 (18%) | Swallows (4), woodpeckers (3), plovers (2), American sparrows (2), hornbills, caracaras, wrens, herons, cranes, swifts, martins, loons, chachalacas, cuckoos, crows, pheasants, tits, jays, eagles, sandpipers, hawks, unspecified bird. |

| Indicating food (ripe wild foods, honey, time to harvest crops, likelihood of good harvest, presence of prey animals) | 29 (18%) | Honeyguides (6), unspecified bird (6), doves (3), cuckoos (2), honeyeaters, woodpeckers, bowerbirds, woodswallows, whistlers, thornbills, rails, new world blackbirds, bee-eaters, finches, geese, jays |

| Predicting weather (storms, clear, wind, drought) | 20 (13%) | Crows (2), herons (2), hawks (2), cuckoos (2), gulls (2), eagles, larks, turkeys, frigatebirds, loons, caracaras, owls, sandpipers, ducks, unspecified bird. |

| Indicating seasonal change (spring, summer, winter, rainy season, dry season) | 18 (11%) | Nightjars (2), sandpipers, meadowlark, American sparrows, trogons, hornbills, cuckoos, robins, rails, rollers, tits, typical owls, kingfishers, ducks, thrushes, snipes, unspecified bird. |

| Indicating the presence of animals | 16 (10%) | Unspecified bird (3), hawks (2), egrets, starlings, babblers, nightjars, honeyeaters, falcons, woodcreepers, eagles, jays, toucans, kingfishers |

| Other (including: indicating camps nearby, moon phases, other people ahead, women’s menses, teaching) | 16 (10%) | Unspecified bird (4), monarchs, crows, nightjars, meadowlark, plovers, chickadees, hummingbirds, loons, jays, weavers, new world blackbirds, kingfishers |

| Indicating time of day | 10 (6%) | Unspecified bird (4), hornbills, honeyeaters, new world blackbirds, pheasants, bluebirds, Asian barbets |

| Warnings or other messages for non-humans | 8 (5%) | Hawks, honeyeaters, parrots, turkeys, turacos, hornbills, African barbets, chats |

| Indicating water | 7 (4%) | Egrets, starlings, waxbills, sandgrouse, guineafowl, parrots, doves |

| Bringing news of visitors to come | 4 (3%) | Cuckoos, whistlers, fantails, unspecified bird. |

Types of signs that were categorized as informationally ecological and the bird groups associated with them. Percentages are out of total ecological signs (155). Owls are listed by order.

| Message type . | Instances (%) . | Bird-as-sign-vehicle (bird group) . |

|---|---|---|

| Signaling rain (or snow) | 29 (18%) | Swallows (4), woodpeckers (3), plovers (2), American sparrows (2), hornbills, caracaras, wrens, herons, cranes, swifts, martins, loons, chachalacas, cuckoos, crows, pheasants, tits, jays, eagles, sandpipers, hawks, unspecified bird. |

| Indicating food (ripe wild foods, honey, time to harvest crops, likelihood of good harvest, presence of prey animals) | 29 (18%) | Honeyguides (6), unspecified bird (6), doves (3), cuckoos (2), honeyeaters, woodpeckers, bowerbirds, woodswallows, whistlers, thornbills, rails, new world blackbirds, bee-eaters, finches, geese, jays |

| Predicting weather (storms, clear, wind, drought) | 20 (13%) | Crows (2), herons (2), hawks (2), cuckoos (2), gulls (2), eagles, larks, turkeys, frigatebirds, loons, caracaras, owls, sandpipers, ducks, unspecified bird. |

| Indicating seasonal change (spring, summer, winter, rainy season, dry season) | 18 (11%) | Nightjars (2), sandpipers, meadowlark, American sparrows, trogons, hornbills, cuckoos, robins, rails, rollers, tits, typical owls, kingfishers, ducks, thrushes, snipes, unspecified bird. |

| Indicating the presence of animals | 16 (10%) | Unspecified bird (3), hawks (2), egrets, starlings, babblers, nightjars, honeyeaters, falcons, woodcreepers, eagles, jays, toucans, kingfishers |

| Other (including: indicating camps nearby, moon phases, other people ahead, women’s menses, teaching) | 16 (10%) | Unspecified bird (4), monarchs, crows, nightjars, meadowlark, plovers, chickadees, hummingbirds, loons, jays, weavers, new world blackbirds, kingfishers |

| Indicating time of day | 10 (6%) | Unspecified bird (4), hornbills, honeyeaters, new world blackbirds, pheasants, bluebirds, Asian barbets |

| Warnings or other messages for non-humans | 8 (5%) | Hawks, honeyeaters, parrots, turkeys, turacos, hornbills, African barbets, chats |

| Indicating water | 7 (4%) | Egrets, starlings, waxbills, sandgrouse, guineafowl, parrots, doves |

| Bringing news of visitors to come | 4 (3%) | Cuckoos, whistlers, fantails, unspecified bird. |

| Message type . | Instances (%) . | Bird-as-sign-vehicle (bird group) . |

|---|---|---|

| Signaling rain (or snow) | 29 (18%) | Swallows (4), woodpeckers (3), plovers (2), American sparrows (2), hornbills, caracaras, wrens, herons, cranes, swifts, martins, loons, chachalacas, cuckoos, crows, pheasants, tits, jays, eagles, sandpipers, hawks, unspecified bird. |

| Indicating food (ripe wild foods, honey, time to harvest crops, likelihood of good harvest, presence of prey animals) | 29 (18%) | Honeyguides (6), unspecified bird (6), doves (3), cuckoos (2), honeyeaters, woodpeckers, bowerbirds, woodswallows, whistlers, thornbills, rails, new world blackbirds, bee-eaters, finches, geese, jays |

| Predicting weather (storms, clear, wind, drought) | 20 (13%) | Crows (2), herons (2), hawks (2), cuckoos (2), gulls (2), eagles, larks, turkeys, frigatebirds, loons, caracaras, owls, sandpipers, ducks, unspecified bird. |

| Indicating seasonal change (spring, summer, winter, rainy season, dry season) | 18 (11%) | Nightjars (2), sandpipers, meadowlark, American sparrows, trogons, hornbills, cuckoos, robins, rails, rollers, tits, typical owls, kingfishers, ducks, thrushes, snipes, unspecified bird. |

| Indicating the presence of animals | 16 (10%) | Unspecified bird (3), hawks (2), egrets, starlings, babblers, nightjars, honeyeaters, falcons, woodcreepers, eagles, jays, toucans, kingfishers |

| Other (including: indicating camps nearby, moon phases, other people ahead, women’s menses, teaching) | 16 (10%) | Unspecified bird (4), monarchs, crows, nightjars, meadowlark, plovers, chickadees, hummingbirds, loons, jays, weavers, new world blackbirds, kingfishers |

| Indicating time of day | 10 (6%) | Unspecified bird (4), hornbills, honeyeaters, new world blackbirds, pheasants, bluebirds, Asian barbets |

| Warnings or other messages for non-humans | 8 (5%) | Hawks, honeyeaters, parrots, turkeys, turacos, hornbills, African barbets, chats |

| Indicating water | 7 (4%) | Egrets, starlings, waxbills, sandgrouse, guineafowl, parrots, doves |

| Bringing news of visitors to come | 4 (3%) | Cuckoos, whistlers, fantails, unspecified bird. |

Supernaturals (Table 2) include named deities, demiurges, or spirits sending messages via birds, as well as any explicit reference to extra-phenomenal agency, such as Congolese Spotted Eagle-owls (Bubo africanus) serving Tembo sorcerers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo as a form of telephone with which to communicate with each other over long distances (Kizungu et al. 1998:113). Because we excluded many forms of spiritual or non-ecological person–bird relationships that were not strictly sign-related, our supernatural category under-represents the numerous reports of people’s communications with birds in spirit worlds, dreams, healing, and sorcery. It is a conservative estimate of bird-sign with explicitly supernatural agency.

Ecological signs or indicators include the description of interactions between birds and other animals, plants, seasons, and other environmental knowledge (Table 3). They often point to subtle or indirect ecological relationships (Wyndham 2009). This kind of sophisticated knowledge comes from sustained empirical observation (often hypothesizing and testing, Liebenberg 1990:29), phenomenological connectedness and openness, and local institutions of trans-generational education in which young people are encouraged to cultivate honed awareness in their environments (Wyndham 2010).

An example of the level of detailed understanding that underlies many ecological indicators can be found in the Muyuw language of Papua New Guinea, for whom the Rainbow Bee-eater’s (Merops ornatus) onomatopoeic local name, kelkil, and call, kilkilkil, indicate the approaching harvest season. The bird’s call approximates the Muyuw word -kil which can be both a verb meaning “to dig up yams” and a noun “the stick used to dig up yams”. Reduplicated as it is in the bird’s call, it implies the continuous action of digging up yams, which is done within a month of first hearing the bird’s song (Damon 1990:1). This attention to detailed ethology and environmental patterns is characteristic of the kind of ecological readings of birds’ behavior and vocalization recorded in our study. Reading birds to predict the weather was common in our sample; other subject matter included listening to and interpreting birds’ alarm calls warning of the presence of snakes or predators; knowing that seeing or hearing a certain bird indicates the presence of certain other animals, or of a water source. We note that though we distinguished agency (i.e. where the information is originating, for example from a deity or the bird itself) many if not most cultural descriptions do not separate supernatural from natural—these categories are somewhat artificial in many cases. For example, a person might be instructed in a dream to look for certain ecological details. The third, largest origin/ agency of signs category consists of those that are neither explicitly natural nor supernatural. Over half of all sign instances, these were composed mainly of the omen- and luck-signs.

While compiling our database we encountered 51 examples of warblish, defined by Sarvasy (2016:766) as the “vocal imitation of avian vocalizations by humans, using existing non-onomatopoeic word(s).” Because our search prioritized instances in which the bird was clearly thought to be a sign, this 8% of all bird messages we transcribed is a low estimate of how common warblish may be in societies worldwide. Note that this percentage is based on a larger dataset of 616 instances of bird “messaging”, which includes all the warblish excerpts we encountered. As not all warblish was considered a “sign” as we defined it, all but 18 were culled from our final “bird sign” dataset. Table 4 provides several representative examples of warblish, and Figure 5 shows which bird groups showed up as sources of warblish.

Examples of warblish. Birds are identified to the nearest identified taxon, and as group (except for owl, identified by order).

| Warblish example . | Bird group . |

|---|---|

| “The cries of birds are interpreted in terms of human conversation: thus the female hornbill says to her mate, “I’m going; I’m going; I’m going to our village;” to which the male replies, “Don’t go. The rain has come; let us plant.” (Bucerotidae; Ovimbundu; Angola; Hambly 1934:158). | Hornbills |

| The “pigeon says, Tu kolela oku iva (‘We believe in stealing’)” (Columbidae; Ovimbundu; Angola; Hambly 1934:135). | Pigeons |

| Its “hoot is interpreted as kurúsi mukúri, mukúri meaning ‘died’ and kurúsi being an imitation of the sound with no additional significance; Lumholtz, writing at the turn of the century, reported that the Rarámuri understood owls to say, ‘Chu-i, chu-i, chu-i’ = ‘dead, dead, dead’” (Strigiformes; Tarahumara; Mexico; Merrill 1988:162). | Owls |

| The wagtail can be “heard speaking in the cattle-pen, and saying, ‘Dig extensively this year. You will buy many cattle [with the corn].’” (Motacilla sp. Zulu; Southern Africa; Callaway 1868:131). | Wagtails |

| “The Nepe-e, Summer bringers [either White-throated Sparrow or White-crowned Sparrow], sing, ‘The leaves are budding and summer is coming.’” (Zonotrichia albicollis or Z. leucophrys; Blackfoot; United States; McClintock 1968:482). | American Sparrows |

| When “a crow is crying kaw kaw, eat, eat! Its tail points towards something dead for the vultures to eat it is a bad omen for engagement” (Corvidae; Gond; India; Elwin 1947:87). | Crows |

| The Red-capped Lark “has a zig-zagged flight that rises and falls, and at the peak of its zig-zag it makes a clattering sound with its wings and produces an extended rising tone. In this call the [Khoi] hears the words Om˙ dire!, that is ‘fix up the hut!’, which is an admonition to the women to tighten the rush mats of the hut, for this bird call is supposed to be heard especially when a storm is approaching” (Calandrella cinerea; Khoi; Southern Africa; Schultze et al. 1907:183). | Larks |

| When a small wild canary “sings before a person or on the hut roof, this means that a white visitor will arrive, for the bird, they believe sings ‘misti puriciu, misti puriciu,’ (A white person is arriving).” (Serinus spp.; Aymara; Andes; La Barre 1948:176). | Finches |

| “During pine nut season, people talked to the Mountain Chickadee, asking, ‘How is your mother?’ She replies, ‘chi chi, bi, bi,bi’ (she is good, good, good)” (Poecile gambeli; N. Paiute; United States; Fowler 2013:166). | Chickadees |

| The Long-tailed Meadowlark’s “healing song goes ‘with the knife it was, with the knife it was,’ alluding to the moment when the bird would have been stabbed with a knife in its chest that shows still bloodied; this bird possesses special powers to discern a person’s nature and foresees future events […] connecting the human with the divine” (Leistes loyca; Mapuche; Chile; Aillapan and Rozzi 2004:5). | New World Blackbirds |

| Warblish example . | Bird group . |

|---|---|

| “The cries of birds are interpreted in terms of human conversation: thus the female hornbill says to her mate, “I’m going; I’m going; I’m going to our village;” to which the male replies, “Don’t go. The rain has come; let us plant.” (Bucerotidae; Ovimbundu; Angola; Hambly 1934:158). | Hornbills |

| The “pigeon says, Tu kolela oku iva (‘We believe in stealing’)” (Columbidae; Ovimbundu; Angola; Hambly 1934:135). | Pigeons |

| Its “hoot is interpreted as kurúsi mukúri, mukúri meaning ‘died’ and kurúsi being an imitation of the sound with no additional significance; Lumholtz, writing at the turn of the century, reported that the Rarámuri understood owls to say, ‘Chu-i, chu-i, chu-i’ = ‘dead, dead, dead’” (Strigiformes; Tarahumara; Mexico; Merrill 1988:162). | Owls |

| The wagtail can be “heard speaking in the cattle-pen, and saying, ‘Dig extensively this year. You will buy many cattle [with the corn].’” (Motacilla sp. Zulu; Southern Africa; Callaway 1868:131). | Wagtails |

| “The Nepe-e, Summer bringers [either White-throated Sparrow or White-crowned Sparrow], sing, ‘The leaves are budding and summer is coming.’” (Zonotrichia albicollis or Z. leucophrys; Blackfoot; United States; McClintock 1968:482). | American Sparrows |

| When “a crow is crying kaw kaw, eat, eat! Its tail points towards something dead for the vultures to eat it is a bad omen for engagement” (Corvidae; Gond; India; Elwin 1947:87). | Crows |

| The Red-capped Lark “has a zig-zagged flight that rises and falls, and at the peak of its zig-zag it makes a clattering sound with its wings and produces an extended rising tone. In this call the [Khoi] hears the words Om˙ dire!, that is ‘fix up the hut!’, which is an admonition to the women to tighten the rush mats of the hut, for this bird call is supposed to be heard especially when a storm is approaching” (Calandrella cinerea; Khoi; Southern Africa; Schultze et al. 1907:183). | Larks |