-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Mukesh Kumar, Madelena Stauss, Philip Taylor, Laura Maursetter, Alexander Woywodt, 10 tips for providing kidney care to persons in prison, Clinical Kidney Journal, Volume 18, Issue 5, May 2025, sfaf090, https://doi.org/10.1093/ckj/sfaf090

Close - Share Icon Share

ABSTRACT

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is prevalent in prisons and most nephrologists see persons in prison in various clinical settings. These encounters are often fraught with challenges around logistics and communication with healthcare providers staffing the prison. Preplanning clinic visits along with education for teams can improve care and ease concerns. Access to virtual consultations in prisons is variable despite it being shown to considerably improve access to care. Access to patient information material is another area for improvement, given that persons in prison are not usually allowed internet access. Another issue is handover of care when persons in prison are transferred between facilities or when they re-enter the community after release from prison. Providing care to persons in prison with established kidney failure is typically challenging, although nephrologists do provide dialysis in prisons. Data are sparse regarding access to transplantation, and the situation differs between countries, but persons in prison face challenges when accessing transplantation and posttransplant care. Palliative care for persons in prison with CKD who decide against dialysis or where dialysis seems incongruent with goals is not always available. Persons in prison are at a higher-than-average risk of CKD and nephrologists can impact outcomes by focusing on modifying these risk factors during clinical encounters. Departments and institutions should work on communication with their prisons and with structured approaches to improve renal care for this unique and vulnerable population. We suggest that nephrologists share the 10 tips with their teams and become advocates for patients with CKD in prison.

INTRODUCTION

The global prison population totals ≈11.5 million people [1] with a trend toward longer sentences and increasing age of people in prison. As a result, chronic health conditions such as hypertension, diabetes and CKD are increasingly common in prison [2, 3]. Persons in prison with CKD face multiple challenges [4, 5] and they may be disproportionately affected by CKD [6]. The fact that they typically require an escort to clinics outside prison is one key challenge. Dialysis in prisons is also difficult and not universally available, even in well-resourced economies [7], and persons in prison have reduced access to transplantation [8–11]. Significant opportunities exist in the care of these patients, e.g. where admission to prison can be an opportunity to address conditions such as hypertension and diabetes and to identify CKD. The United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (Mandela rules) stipulate that persons in prison should receive care that is similar to those in the community [12] and CKD should be no exception. Most nephrologists have only sporadic contact with persons in prison and the prevalence of such patients in our clinics also depends on the incarceration rates, which vary considerably. In the USA for example, 2.3 million people (0.7% of the population) are in prison [13], whereas rates are much lower in Europe. However, even if seen infrequently, persons in prison represent a unique and vulnerable population. Our 10 tips aim to provide nephrologists with a toolbox to gradually turn aspiration into reality and improve the care for this unique population of patients.

Tip 1: Be aware of your local prison infrastructure and the electronic health record and use admission to prison as an opportunity

Knowledge of the local prison infrastructure is a good starting point and in many countries such information is in the public domain. As far as healthcare is concerned, all prisons feature some form of healthcare, usually with nursing staff and prison doctors who provide an initial assessment on receiving a new prisoner. Areas of healthcare that these services often focus on include primary care, substance misuse including alcohol and mental health.

Important differences exist in terms of the electronic health record, which is usually distinct from that outside prison and not usually electronically accessible to nephrologists. In most countries, persons in prison are not allowed to know the date or time frame for their follow-up appointments. In the USA, the prisoner's record does not connect to their health record before or after incarceration, making retrieval of historical data or data after release challenging.

Admission to prison is an important opportunity to identify patients with kidney disease, and coming to prison usually involves a medical screening that can become an opportunity to find and treat chronic diseases. Unsurprisingly, healthcare resources in jails are focused on acute problems but chronic conditions are usually also registered on admission. Offering an educational talk to local prison doctors and nurses may be an excellent opportunity to improve the situation and to forge important links for cooperation.

Tip 2: Plan clinic visits, allow extra time where possible and address stigma through education

Face-to-face clinic visits are often difficult to organise for persons in prison, as most require an escort. In many countries, prisons are located in more rural areas often far away from healthcare facilities, a phenomenon referred to as ‘spatial injustice’ [7]. It is useful to try and view appointments as an opportunity to try and get tests and imaging done at the same time: recalling a person in prison later for tests often incurs delay in the care pathway and is overall much more cumbersome than in patients who are not in prison. Being courteous towards prison staff is important, as is alerting them when extra time is required, since escorting patients to an outpatient appointment can be a stressful experience for them, particularly when patients are in a more high-security category. Where complex discussions are anticipated, e.g. around dialysis modality choice or transplantation, nephrologists may want to consider planning extra time. It is also the case that there is often concern among clinic staff, especially where persons in prison are seen infrequently. In these circumstances, alerting and reassuring nursing colleagues, trainees and students in advance can be considered. If time allows, clinicians could educate these groups about aspects of prison healthcare before or after the encounter.

Tip 3: Address modifiable risk factors of CKD, support research into CKD in prison and optimise nutrition

Worldwide, the prison population is aging and a disproportionate number of persons in prison come from poverty [13]. The Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes guidelines identify that older age and socio-economic hardship are risk factors for CKD [14, 15]. In addition, there has been evidence in the USA that the populations eligible for Medicaid (low-income public health insurance) had more kidney disease in those who were incarcerated than those who were not [16]. This makes the prison population a suitable target for CKD management interventions. When entering prison, the intake health screen affords an opportunity for intervention to not only diagnose CKD (see Tip 1) but also to slow the progression of disease. There was one study that looked at the incidence of CKD in a maximum-security US prison, which showed 2% have CKD (with a very loose definition of CKD) [17], while another study showed 25% of newly incarcerated people in Australia screened positive [18]. This shows that the rates of CKD are widely variable.

Modifiable CKD risk factors can be addressed with simple interventions for blood pressure (BP) management, cholesterol control, weight management and minimizing proteinuria—all treatments known to impact CKD and cardiovascular outcomes. A study was done on veterans who had recent or past incarcerations and multivariable regression analysis showed that a recent incarceration led to significantly more uncontrolled BP than in those who had not been incarcerated [adjusted odds ratio 1.57 (95% confidence interval 1.09–2.26)] [19].

Unfortunately, little is known about the prevalence or outcomes of CKD in prisons [20] because outcome studies in the correctional system are almost non-existent. This is likely related to issues with approval by institutional review boards, difficulty in recruitment and follow-up and a lack of incentives to track health outcomes of inmates. Most studies looking at other chronic conditions, including diabetes, have shown that medications for persons in prison have been underprescribed when compared with the general population [21], so one can infer that this is also happening for CKD. A study in New York showed that it was cost effective to both screen and treat hypertension and diabetes in the US prison population to prevent complications, including end-stage renal disease (ESRD) [22]. Nephrologists should strive to provide the same preventive measures to patients in prison as to the general CKD patients and advocate for the availability of medications that are known to be effective. In addition, nephrologists should lead research to show CKD outcomes in prisons and national registries of dialysis in prison should be the standard.

Nutrition plays a key role in disease modification of CKD and dietician input is part of routine care. Unfortunately, the dietary choices in the prison system are limited. Inmates will often supplement their diets with food from a centralized ‘store’ that offers prepackaged and high sodium foods for purchase. It is likely that the outcomes for CKD prevention and progression would result in cost savings if improved dietary choices were provided [18].

Tip 4: Work with prisons to provide patients with access to telemedicine and to web-based patient information

Virtual consultations through a variety of mechanisms have become more common because of the COVID-19 pandemic [23, 24]. However, in most countries, persons in prison are not allowed mobile phones and access to computers is also typically restricted. Some countries have endorsed telemedicine visits nationally [25], but other countries have limited experience [26]. We recommend that nephrologists try and work with their local prisons to explore whether this approach is feasible. Virtual court hearings are quite common and many prisons have a well-equipped video suite. Some countries allow video calls with family, which provide further familiarity with this process [27]. Under these circumstances it is difficult to see how a prison could deny video consultations if a government allows. Access to patient information is often equally restricted in prisons (e.g. access to departmental patient information videos or animations accessed via the internet). We feel that persons in prison should have the same access to patient information as all other patients and nephrologists and their teams should try and overcome barriers. Where this cannot be achieved, viewing of such material in clinic rooms may be possible after face-to-face outpatient appointments.

Tip 5: Support handover when persons in prison are moved and know the rules and regulations around medical ‘holds’

Prisons are frequently chaotic places with a high turnover [28] and persons in prison are often transported between facilities at short notice. Handover between nephrologists should be attempted wherever possible. Where there is a clinical need not to interrupt an episode of care, persons in prison may be eligible for a medical ‘hold’ and it is important for nephrologists to know the rules around holds where they exist [29]. Use of a hold could be appropriate for a patient requiring treatment for an active glomerular disease or during preparation for immediate dialysis initiation. It is crucial that nephrologists state their recommendation for a clinical hold in accordance with laws and regulations, typically through correspondence to the prison governor (or equivalent). However, limiting the knowledge of this hold to the patient is important so there is not an increased security concern. Clinicians should make sure the clinical reasoning is sound and that a hold is well justified.

Tip 6: Aim for continuity of care after incarceration

The importance of continuity of care and communication is clearly reflected in the rules and guidelines concerning prison healthcare [12]. This is particularly relevant for some complex patients in our specialty, e.g. patients close to dialysis, those with glomerular disease or patients with a functioning transplant. In England and Wales, before release, providers are expected to

...Carry out a pre-release health assessment for people with complex needs. This should be led by primary healthcare and involve multidisciplinary team members and the person. It should take place at least 1 month before the date the person is expected to be released. [30]

This underlines the importance of nephrologists forging relations with the prison healthcare team, since without their participation, the release process risks being suboptimal. Some patients may be released unexpectedly, and it is worth letting persons in prison know how to contact departments in this scenario. Such contact could include a request for follow-up care or for hospital-only medication, such as immunosuppression. With permission from the patient, nephrologists could also consider involving the patient's family members early, with a view to seeking their support on release. Be mindful, however, in many countries families will not be allowed to know of or attend clinic appointments while the patient is in prison. Peer supporters and voluntary sector organisations can help with the transition to post-release care.

Tip 7: Provide persons in prison with equal access to dialysis, mitigate against transport issues and consider ‘home’ therapy

In-centre haemodialysis (ICHD) remains the most utilised dialysis modality in persons in prison, however, it poses significant challenges, particularly with regards to transport times and security concerns [7]. In the USA, some prisons have dedicated in-prison dialysis units, but these tend to be located in high-security prisons, which in effect requires any person in prison with ESRD to be in a high-security prison even if their sentence would allow for a lower security prison with more privileges and opportunities. For example, high-security facilities may not have the same options for work release or access to alcohol rehabilitation programs etc, so people who need dialysis may be disadvantaged in terms of access to resources, subsequently affecting the duration of incarceration or successful reintegration after release.

For those undergoing ICHD, there is often limited flexibility in dialysis centres to rearrange dialysis sessions, e.g. when an escort is not available or due to unforeseen incidents in the prison. Persons in prison may miss their ICHD slot, and inconsistent dialysis therapy and interrupted care leads to worsened morbidity and mortality. However, mitigating against interruptions to treatment due to logistical issues can lie outside the control of the dialysis unit. ‘Home’ therapy in the form of home haemodialysis (HHD) or peritoneal dialysis (PD) in prison can help overcome barriers, address transport issues [7, 4, 31] and result in cost savings and security benefits [32]. Safety and hygiene standards will need to be met, and prisons will need to transform a specific area for the provision of HHD (usually within the medical wing) and PD with appropriate provision of water, electricity and space. It is important to note that the need for handcuffs or other physical restraints can pose a threat to arteriovenous fistulae. There needs to be fastidious counting and secure storage of supplies, which can pose a security risk (e.g. fistula needles and non-pH-neutral substances such as dialysate or buffers). Human immunodeficiency virus–associated nephropathy is more prevalent in persons in prison [4], as are other blood-borne viruses, therefore stringent infection control measures need to be upheld for both patients and staff.

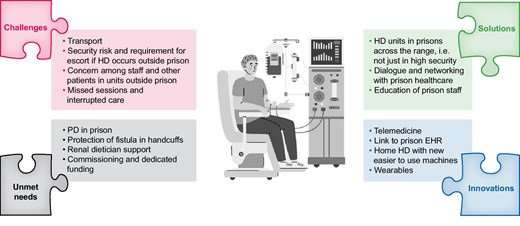

Finally, regular review of dialysis patients in prison is helpful although vetting procedures on entry can be tedious and visits should be planned well ahead. Furthermore, electronic devices cannot be brought into most prisons, therefore nephrology staff should ensure they arrive well prepared in terms of results, dialysis parameters and other electronic health records. Real time bi-directional remote biometric monitoring of dialysis parameters will likely not be possible due to security risks of connectivity and other innovative solutions should be sought (e.g. utilisation of wearable technology once it is more widely available). Fig. 1 highlights some of the challenges and potential solutions to providing dialysis care in prisons.

Challenges, solutions, innovations and unmet needs around dialysis in prisons. Icon modified from a template purchased under commercial licence from Vectorstock in November 2024. EHR denotes electronic health record.

Tip 8: Provide equal access to transplantation and posttransplant care and be aware of the national guidance on persons in prison as live donors

Persons in prison should expect the same standards of healthcare that are available in the community [12] and equal access to transplantation should be part of this. This is mirrored in many national guidelines, such as the United Network for Organ Sharing and Transplantation in the USA. Despite such guidance, access to transplant is by no means universal in practice [33]. A 2019 study reported that only 19% of transplant centres in the USA performed kidney transplants on persons in prison [34] and factors such as the type of crime and length of sentence are sometimes considered in transplant assessment [35]. In 2000, a decision to deny a prisoner assessment for transplantation was upheld despite a legal challenge, on the grounds that dialysis was an ‘acceptable’ treatment [36]. Nephrologists should promote transplant assessment when they see eligible patients and they should work with other stakeholders to provide good posttransplant care. It is useful to have detailed discussions with prison staff when patients are activated on the transplant list and plan for the scenario where a person in prison is called in for a transplant, especially during the night. Whether persons in prison can be live donors has been controversial for a long time, not least due to the fact that kidneys from executed persons in prison were previously transplanted [37]. Persons in prison are uniquely vulnerable to pressure and atonement may be a motive for live donation. Some have argued that live donation should lead to a reduced sentence [38]. Guidelines on live donor candidacy in persons in prison exist in the USA, Australia and the UK [9]. Their detailed discussion is beyond the scope of this article, but live donation from persons in prison is often regarded as permissible when no other live donor options exist. Altruistic donation is often viewed with concern, mostly because media publicity could cause reputational damage to transplant programs.

Tip 9: Provide good-quality end-of-life care to persons in prison

The prison population is aging and end-of-life care to persons in prison with CKD is increasingly common. Several countries have provided guidelines for palliative care for persons in prison [39, 40], which can take the form of an in-prison hospice or external ‘in reach’ services [41]. Communicating results in a timely and sensitive manner can be problematic, for example when imaging has demonstrated an unexpected finding of metastatic malignancy. A close working relationship between nephrology departments and prison healthcare providers will help, with a commitment to collaborate and share care. Educating prison staff on the common symptoms encountered on withdrawal of dialysis or conservative kidney care is also important, as these may differ from those encountered in other scenarios, such as cancer. Such symptoms may include involuntary muscle twitching, fluid overload and itching. Another common issue is access to ‘as required’ medication for symptom relief, as many of these are controlled substances and availability may be hampered out of hours. Where possible, the prisoner should be established on a stable method of symptom control, such as continuous subcutaneous infusion. The level of healthcare intervention that can be provided will differ between correctional facilities, and moving to an alternative prison may be considered. Some prisons may also provide inmate hospice volunteers. However, consideration also needs to be given to the relationships that may have formed during long sentences, and they may not want to move. Multidisciplinary meetings with a named coordinator are helpful and decisions need to be made in conjunction with the prisoner. Finally, applying for compassionate release from prison can be considered, typically where life expectancy is a few months. If successful, the issues previously highlighted regarding transfer and continuity of care after release need to be considered (see Tip 6).

Tip 10: Become a resource and an advocate for these patients

Nephrologists can take a leading role and become ambassadors for these patients and a force for good to improve the overall care of persons in prison.

Prison physicians are often overwhelmed by the volume of care needed and nephrologists could reserve space in their practice to have the availability to see persons in prison when referred and to be available to answer questions when they arise. This will create a network that involves prison doctors and nurses. Such links can be further improved through educational events for prison staff.

Nephrologists should connect with the leaders in the prison system to suggest CKD screening measures that should be appropriately performed because they are cost effective [22]. In those with findings of microalbuminuria, decreased estimated glomerular filtration rate or high BP, structured advice can be provided with suggestions for standard management, including the timing of referral to specialty care. In seeing patients with advanced CKD, nephrologists should be guided by their clinical acumen in the same way they would treat patients outside of prison. In our experience, it is important to provide clear recommendations in office visit notes and letters and to ensure that guidance is not overruled by non-medical staff (Table 1). Support may also be useful where there are issues with availability of medications (tolvaptan, sodium–glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors), changes in dietary choices, transplant or options to make exercise a routine practice. Nephrologists should continue to argue the case with the prison leadership and educate them on the standard of care, where appropriate.

| Tip 1: Be aware of your local prison infrastructure and the electronic health record and use admission to prison as an opportunity. |

| Tip 2: Plan clinic visits, allow extra time where possible and address stigma through education. |

| Tip 3: Address modifiable risk factors of CKD, support research into CKD in prison and optimise nutrition. |

| Tip 4: Work with prisons to provide patients with access to telemedicine and to web-based patient information. |

| Tip 5: Support handover when persons in prison are moved and know the rules and regulations around medical ‘holds’. |

| Tip 6: Aim for continuity of care after incarceration. |

| Tip 7: Provide persons in prison with equal access to dialysis, mitigate against transport issues and consider ‘home’ therapy. |

| Tip 8: Provide equal access to transplantation and posttransplant care and be aware of the national guidance on persons in prison as live donors. |

| Tip 9: Provide good-quality end-of-life care to persons in prison. |

| Tip 10: Become a resource and an advocate for these patients. |

| Tip 1: Be aware of your local prison infrastructure and the electronic health record and use admission to prison as an opportunity. |

| Tip 2: Plan clinic visits, allow extra time where possible and address stigma through education. |

| Tip 3: Address modifiable risk factors of CKD, support research into CKD in prison and optimise nutrition. |

| Tip 4: Work with prisons to provide patients with access to telemedicine and to web-based patient information. |

| Tip 5: Support handover when persons in prison are moved and know the rules and regulations around medical ‘holds’. |

| Tip 6: Aim for continuity of care after incarceration. |

| Tip 7: Provide persons in prison with equal access to dialysis, mitigate against transport issues and consider ‘home’ therapy. |

| Tip 8: Provide equal access to transplantation and posttransplant care and be aware of the national guidance on persons in prison as live donors. |

| Tip 9: Provide good-quality end-of-life care to persons in prison. |

| Tip 10: Become a resource and an advocate for these patients. |

| Tip 1: Be aware of your local prison infrastructure and the electronic health record and use admission to prison as an opportunity. |

| Tip 2: Plan clinic visits, allow extra time where possible and address stigma through education. |

| Tip 3: Address modifiable risk factors of CKD, support research into CKD in prison and optimise nutrition. |

| Tip 4: Work with prisons to provide patients with access to telemedicine and to web-based patient information. |

| Tip 5: Support handover when persons in prison are moved and know the rules and regulations around medical ‘holds’. |

| Tip 6: Aim for continuity of care after incarceration. |

| Tip 7: Provide persons in prison with equal access to dialysis, mitigate against transport issues and consider ‘home’ therapy. |

| Tip 8: Provide equal access to transplantation and posttransplant care and be aware of the national guidance on persons in prison as live donors. |

| Tip 9: Provide good-quality end-of-life care to persons in prison. |

| Tip 10: Become a resource and an advocate for these patients. |

| Tip 1: Be aware of your local prison infrastructure and the electronic health record and use admission to prison as an opportunity. |

| Tip 2: Plan clinic visits, allow extra time where possible and address stigma through education. |

| Tip 3: Address modifiable risk factors of CKD, support research into CKD in prison and optimise nutrition. |

| Tip 4: Work with prisons to provide patients with access to telemedicine and to web-based patient information. |

| Tip 5: Support handover when persons in prison are moved and know the rules and regulations around medical ‘holds’. |

| Tip 6: Aim for continuity of care after incarceration. |

| Tip 7: Provide persons in prison with equal access to dialysis, mitigate against transport issues and consider ‘home’ therapy. |

| Tip 8: Provide equal access to transplantation and posttransplant care and be aware of the national guidance on persons in prison as live donors. |

| Tip 9: Provide good-quality end-of-life care to persons in prison. |

| Tip 10: Become a resource and an advocate for these patients. |

CONCLUSION

Nelson Mandela is often quoted as saying, in 1955, that no one truly knows a nation until one has been inside its jails [42]. His legacy continues in the United Nations Mandela rules (Table 2). It is sobering that 70 years later, imprisonment is still a risk to health, with a loss of 2 years of life expectancy for every year spent in prison [43]. As nephrologists, we find a pro/con debate on whether persons in prison should be allowed transplants equally disturbing [44]. Persons in prison with CKD are a small but vulnerable group of our patients and it is upon us as nephrologists to be aware of the risks and challenges in their care (Fig. 2). It is also up to us to work with our teams and with colleagues in prison healthcare to overcome them [6]. We hope that our 10 tips (Table 1) improve awareness among nephrologists, provide inspiration for nephrologists to improve care and motivate some colleagues to become resourceful advocates for these patients.

Challenges in providing renal care to persons in prison. Icons modified from templates purchased under commercial licence from Vectorstock in November 2024.

The United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Persons in Prison (the Nelson Mandela Rules). Excerpts from rules 24–32 (healthcare).

| 24.1. ...Prisoners should enjoy the same standards of health care that are available in the community and should have access to necessary health-care services free of charge without discrimination on the grounds of their legal status. |

| 24.2. Health-care services should be organized...in a way that ensures continuity of treatment and care... |

| 27.1. All prisons shall ensure prompt access to medical attention in urgent cases. Prisoners who require specialized treatment or surgery shall be transferred to specialized institutions or to civil hospitals. |

| 27.2. Clinical decisions may only be taken by the responsible health-care professionals and may not be overruled or ignored by non-medical prison staff. |

| 32.2. ...prisoners may be allowed, upon their free and informed consent and in accordance with applicable law, to participate in clinical trials and other health research accessible in the community if these are expected to produce a direct and significant benefit to their health, and to donate cells, body tissues or organs to a relative. |

| 24.1. ...Prisoners should enjoy the same standards of health care that are available in the community and should have access to necessary health-care services free of charge without discrimination on the grounds of their legal status. |

| 24.2. Health-care services should be organized...in a way that ensures continuity of treatment and care... |

| 27.1. All prisons shall ensure prompt access to medical attention in urgent cases. Prisoners who require specialized treatment or surgery shall be transferred to specialized institutions or to civil hospitals. |

| 27.2. Clinical decisions may only be taken by the responsible health-care professionals and may not be overruled or ignored by non-medical prison staff. |

| 32.2. ...prisoners may be allowed, upon their free and informed consent and in accordance with applicable law, to participate in clinical trials and other health research accessible in the community if these are expected to produce a direct and significant benefit to their health, and to donate cells, body tissues or organs to a relative. |

The United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Persons in Prison (the Nelson Mandela Rules). Excerpts from rules 24–32 (healthcare).

| 24.1. ...Prisoners should enjoy the same standards of health care that are available in the community and should have access to necessary health-care services free of charge without discrimination on the grounds of their legal status. |

| 24.2. Health-care services should be organized...in a way that ensures continuity of treatment and care... |

| 27.1. All prisons shall ensure prompt access to medical attention in urgent cases. Prisoners who require specialized treatment or surgery shall be transferred to specialized institutions or to civil hospitals. |

| 27.2. Clinical decisions may only be taken by the responsible health-care professionals and may not be overruled or ignored by non-medical prison staff. |

| 32.2. ...prisoners may be allowed, upon their free and informed consent and in accordance with applicable law, to participate in clinical trials and other health research accessible in the community if these are expected to produce a direct and significant benefit to their health, and to donate cells, body tissues or organs to a relative. |

| 24.1. ...Prisoners should enjoy the same standards of health care that are available in the community and should have access to necessary health-care services free of charge without discrimination on the grounds of their legal status. |

| 24.2. Health-care services should be organized...in a way that ensures continuity of treatment and care... |

| 27.1. All prisons shall ensure prompt access to medical attention in urgent cases. Prisoners who require specialized treatment or surgery shall be transferred to specialized institutions or to civil hospitals. |

| 27.2. Clinical decisions may only be taken by the responsible health-care professionals and may not be overruled or ignored by non-medical prison staff. |

| 32.2. ...prisoners may be allowed, upon their free and informed consent and in accordance with applicable law, to participate in clinical trials and other health research accessible in the community if these are expected to produce a direct and significant benefit to their health, and to donate cells, body tissues or organs to a relative. |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the helpful discussions with patients past and present who were in prison at the time of our clinical encounters. We are indebted to Dr Ewa Pawlowicz-Slarska (Department of Nephrology, Medical University Lodz, Lodz, Poland), who through her work on renal care for refugees and victims of armed conflict gave us the idea for this project during ERA2024 in Stockholm.

FUNDING

None declared.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

A.W. is on the editorial board of Clinical Kidney Journal and serves as Social Media Editor.

REFERENCES

FindLaw.

Comments