-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Marie Dirix, Ester Philipse, Rowena Vleut, Vera Hartman, Bart Bracke, Thierry Chapelle, Geert Roeyen, Dirk Ysebaert, Gerda Van Beeumen, Erik Snelders, Annick Massart, Katrien Leyssens, Marie M Couttenye, Daniel Abramowicz, Rachel Hellemans, Timing of the pre-transplant workup for renal transplantation: is there room for improvement?, Clinical Kidney Journal, Volume 15, Issue 6, June 2022, Pages 1100–1108, https://doi.org/10.1093/ckj/sfac006

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Since patient survival after kidney transplantation is significantly improved with a shorter time on dialysis, it is recommended to start the transplant workup in a timely fashion.

This retrospective study analyses the chronology of actions taken during the care for patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 5 who were waitlisted for a first kidney transplant at the Antwerp University Hospital between 2016 and 2019. We aimed to identify risk factors for a delayed start of the transplant workup (i.e. after dialysis initiation) and factors that prolong its duration.

Of the 161 patients included, only 43% started the transplant workup before starting dialysis. We identified the number of hospitalization days {odds ratio [OR] 0.79 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.69–0.89]; P < 0.001}, language barriers [OR 0.20 (95% CI 0.06–0.61); P = 0.005] and a shorter nephrology follow-up before CKD stage 5 [OR 0.99 (95% CI 1.0–0.98); P = 0.034] as factors having a significant negative impact on the probability of starting the transplant screening before dialysis. The workup took a median of 8.6 months (interquartile range 5–14) to complete. The number of hospitalization days significantly prolonged its duration.

The transplant workup was often started too late and the time needed to complete it was surprisingly long. By starting the transplant workup in a timely fashion and reducing the time spent on the screening examinations, we should be able to register patients on the waiting list before or at least at the start of dialysis. We believe that such an internal audit could be of value for every transplant centre.

INTRODUCTION

Renal transplantation is the preferred treatment for patients with renal failure, as it increases survival [1–3] and improves quality of life [4]. The time spent on dialysis before transplantation appears to have a directly proportional negative effect on patient survival and possibly also graft survival [5–12]. Therefore, it is increasingly recommended to aim for pre-emptive transplantation, either with a living donor or by timely registration on the waiting list for deceased donor transplantation [13, 14].

Although pre-emptive registration on the transplant waiting list occurs more often in recent years, it is still only performed in a minority of patients [15–17]. Furthermore, a variability in the timing of referral to a transplant centre persists, with some patients spending months to years on dialysis before starting their pre-transplant evaluation [16,18,19]. The recently updated Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes guidelines specifically recommend the referral of potential kidney transplant candidates for evaluation at least 6–12 months before anticipated dialysis initiation in order to facilitate the identification and workup of living donors and to plan for possible pre-emptive transplantation [13]. However, data about the timing of the transplant workup and the time required to complete it are scarce.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This study is a multicentric retrospective analysis evaluating the chronology of actions taken during the care for patients waitlisted for their first kidney transplantation at the Antwerp University Hospital in Belgium. (Pre-)dialysis care of these patients was performed at either the Antwerp University Hospital or one of its referring centres in the province of Antwerp (16 hospitals in total). The transplant workup was performed in the referring centre and the patient was referred to the transplant centre after finalizing the workup to proceed to registration on the waiting list. All physicians (both in the academic centre and in the referring hospitals) used a guidance document for the pre-transplant workup that was developed by the academic centre and is largely based on the European Renal Best Practice (ERBP) guidelines [20].

Population

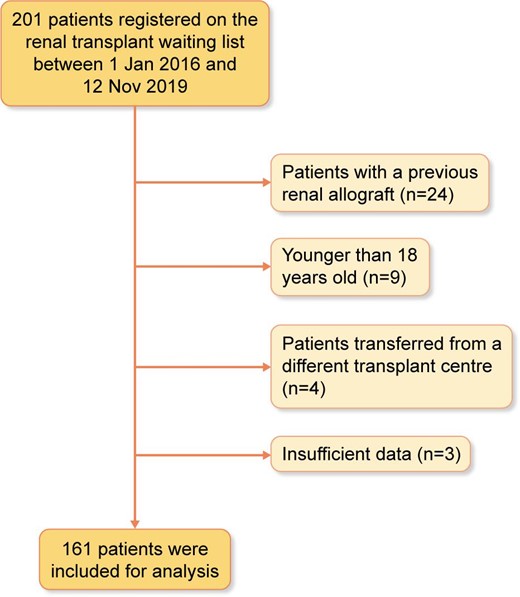

A total of 201 patients were registered on the Antwerp renal transplant deceased donor waiting list between 1 January 2016 and 12 November 2019. Patients were excluded if they were <18 years old (n = 9), if they had received a previous renal allograft (n = 24), if they were transferred from a different transplant centre (n = 4) or if there were no data available on the pre-transplant care period (n = 3). This led to a total number of 161 patients included for analysis (for the exclusion process, see Figure 1). Although this study includes only patients originally waitlisted for a deceased donor transplant, five patients who went through the standard workup for a deceased donor renal transplant were eventually transplanted with a living donor later on. Patients were followed up until 31 January 2020.

Data collected

Based on the available literature, we collected a set of patient-derived variables that might influence the timing of pre-transplant care (for more details on the definitions used, see Table S1 of the supplementary appendix). We examined whether supplementary medical examinations were performed on top of the recommended screening examinations (ERBP guidelines) [20]. We specifically recorded invasive urologic examinations, colonoscopy, gastroscopy and ultrasound of the carotid arteries and assessed whether there was a medical indication for these procedures, as recommended by the aforementioned ERBP guidelines or the national cancer screening guidelines.

We recorded the following key moments during pre-transplant nephrology care: date of the first nephrology visit, date of the nephrology visit when the eGFR was <15 mL/min/1.73 m2 for the first time (i.e. the start of CKD stage 5), date of the first medical examination performed to screen patients for eligibility for transplantation (i.e. the start of workup), date of the first access procedure for dialysis, date of the first dialysis session, date of registration on the renal transplant waiting list, and date of renal transplantation for those who were transplanted during the study period.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with the use of the SPSS Statistics (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Differences between groups were analysed using the Mann–Whitney U-test for continuous variables and the chi-squared test for categorical variables with Yates’ correction for continuity. When the examined numbers were too small, the Fisher's exact test was used. Multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to explore the influence of patient-derived factors on the probability of starting the transplant workup before the start of dialysis. To this end, we initially included all clinically relevant parameters. To avoid over fitting of the model, we selected a final model based on clinical relevance and statistical significance in univariable analysis. We ultimately included seven variables in our model.

We subsequently calculated the workup time for every patient as the number of days between the first transplant screening examination and the ultimate registration on the waiting list. For the multiple linear regression analysis, we selected the variables based on clinical relevance and statistical significance in the simple linear regression analysis. We calculated R² to assess to what extent the combination of independent variables could explain the variance in workup time. In order to fulfil the assumption of normal distribution, we used a logarithmic transformation (log10) of the workup time in both the simple and multiple regression models. All listed P-values are two-tailed. Our study was exempt from institutional review board approval.

RESULTS

Patients

Baseline characteristics at the time of waitlisting are shown in Table 1. The median age was 53 years and 62% were male. Patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) or glomerular disease comprised almost half of the population. Fifty-seven percent of patients were treated with haemodialysis and 29% with peritoneal dialysis at the time of registration on the waiting list. The remaining 14% of patients were pre-emptively registered. Nearly one-fourth of patients had cardiovascular disease, and one in three patients experienced one or more infectious episodes between the start of CKD stage 5 and the moment of registration on the waiting list. One-third of patients mentioned some degree of financial difficulties, and >20% were late referrals. The median time between the first nephrology contact and the start of CKD stage 5 was 41 months (3.4 years).

Timing of the pre-transplant workup

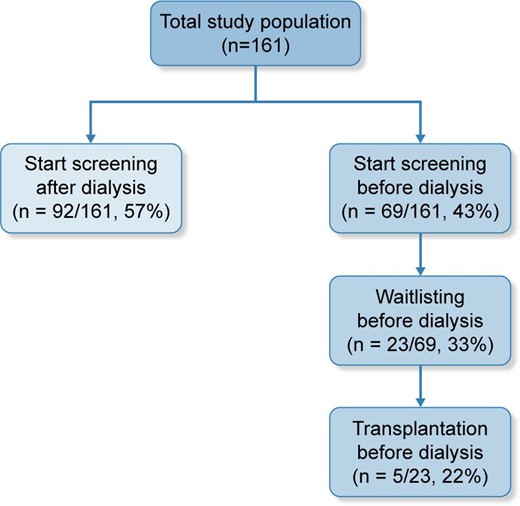

Only 43% (69/161) of patients started their transplant evaluation before the start of dialysis and 32% (51/161) started the evaluation before they had their first dialysis access created. Of the 69 patients who started the transplant workup before the start of dialysis, 23 (33%) were waitlisted before the start of dialysis. This corresponds to 14.2% of the total population. Five of them (7%) were pre-emptively transplanted, three of whom received a kidney from a living donor (Figure 2).

Proportion of patients who started the transplant workup and were registered on the waiting list before the start of dialysis.

Compared with patients who started the transplant workup before the start of dialysis, those who started the transplant workup after dialysis were more often male (71 versus 51%; P = 0.01), more likely to have hypertensive nephropathy and less likely to have ADPKD as the primary renal disease [18 versus 4% (P = 0.0075) and 10 versus 32% (P < 0.001), respectively] (Table 1). They had significantly more cardiovascular disease (32 versus 13%; P = 0.008) and were more often hospitalized between the start of CKD stage 5 and the start of the workup (9 versus 0 days; P < 0.001). As for dialysis modality, they were more frequently treated with haemodialysis than peritoneal dialysis (82 versus 18%).

| . | Total . | Start of transplant workup . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics . | Population (N = 161) . | Before start of dialysis (n = 69) . | After start of dialysis (n = 92) . | P-value . |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 53 (43–64) | 52 (39–61) | 53.5 (45–65) | 0.16 |

| Male, n (%) | 100 (62.1) | 35 (50.7) | 65 (70.7) | 0.01 |

| BMI (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 26.3 (23.4–29.5) | 25.7 (23–29) | 27 (24.5–30) | 0.065 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 14 (8.7) | 5 (7.2) | 9 (9.8) | 0.78 |

| Primary renal disease, n (%) | ||||

| ADPKD | 31 (19.2) | 22 (32.0) | 9 (9.8) | P < 0.001 |

| Diabetic nephropathy | 26 (16.15) | 8 (11.6) | 18 (19.6) | 0.17 |

| Glomerular disease | 35 (21.7) | 14 (20.3) | 21 (22.8) | 0.7 |

| Hypertensive nephropathy | 20 (12.4) | 3 (4.35) | 17 (18.5) | 0.0075 |

| Tubulo-interstitial disease | 17 (10.6) | 8 (11.6) | 9 (9.8) | 0.80 |

| CAKUT | 12 (7.4) | 7 (10.1) | 5 (5.4) | 0.36 |

| Other | 6 (3.7) | 2 (2.9) | 4 (4.3) | 0.70 |

| Unknown | 14 (8.7) | 5 (7.25) | 9 (9.8) | 0.78 |

| Dialysis modality at waitlisting, n (%) | ||||

| Haemodialysis | 92 (57.1) | 17 (24.6) | 75 (81.5) | P < 0.001 |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 46 (28.6) | 29 (42.0) | 17 (18.5) | P < 0.001 |

| Not yet treated with dialysis | 23 (14.2) | 23 (33.3) | NA | |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 38 (23.6) | 11 (15.9) | 27 (29.3) | 0.05 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 38 (23.6) | 9 (13.0) | 29 (31.5) | 0.006 |

| Lung disease | 36 (22.4) | 12 (17.4) | 24 (26.1) | 0.19 |

| Liver disease | 8 (5.0) | 2 (2.9) | 6 (6.5) | 0.47 |

| Psychiatric disease | 25 (15.5) | 8 (11.6) | 17 (18.5) | 0.23 |

| Infection, (between the start of CKD stage 5 and registration on the waiting list) | 54 (33.5) | 17 (24.6) | 37 (40.2) | 0.057 |

| History of malignancy | 9 (5.6) | 2 (2.9) | 7 (7.6) | 0.30 |

| Hospitalization between start of CKD stage 5 and start of transplant workup (days), median (IQR) | 2 (0–11) | 0.00 (0-0) | 9.00 (2–20) | P < 0.001 |

| Psychosocial, n (%) | ||||

| Financial issues | 53 (32.9) | 16 (23.2) | 37 (40.2) | 0.023 |

| Insufficient health insurance | 12 (7.4) | 2 (2.9) | 10 (10.9) | 0.07 |

| Language difficulties | 44 (27.3) | 8 (11.6) | 36 (39.1) | P < 0.001 |

| Complete language barrier | 24 (14.9) | 5 (7.2) | 19 (20.6) | 0.024 |

| Non-adherence | 29 (18.0) | 9 (13.0) | 20 (21.7) | 0.15 |

| Timing of nephrology care | ||||

| Time between first nephrology contact and start of CKD stage 5 (months), median (IQR) | 41.2 (4.3–87) | 61.9 (26.8–133.6) | 20.9 (0–65.2) | P < 0.001 |

| Late referral, n (%) | 35 (21.7) | 5 (7.3) | 30 (32.6) | P < 0.001 |

| Start of workup before first access procedure, n (%) | 51 (31.7) | 51 (74.0) | NA | P < 0.001 |

| Time between start of CKD stage 5 and start of dialysis (months), median (IQR) | 4.8 (0.6–12) | 9.6 (3.4–13) | 2.7 (0.1–10.4) | P < 0.001 |

| Treating centre is renal transplant centre, n (%) | 36 (22.4) | 23 (33.3) | 13 (14.1) | 0.007 |

| . | Total . | Start of transplant workup . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics . | Population (N = 161) . | Before start of dialysis (n = 69) . | After start of dialysis (n = 92) . | P-value . |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 53 (43–64) | 52 (39–61) | 53.5 (45–65) | 0.16 |

| Male, n (%) | 100 (62.1) | 35 (50.7) | 65 (70.7) | 0.01 |

| BMI (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 26.3 (23.4–29.5) | 25.7 (23–29) | 27 (24.5–30) | 0.065 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 14 (8.7) | 5 (7.2) | 9 (9.8) | 0.78 |

| Primary renal disease, n (%) | ||||

| ADPKD | 31 (19.2) | 22 (32.0) | 9 (9.8) | P < 0.001 |

| Diabetic nephropathy | 26 (16.15) | 8 (11.6) | 18 (19.6) | 0.17 |

| Glomerular disease | 35 (21.7) | 14 (20.3) | 21 (22.8) | 0.7 |

| Hypertensive nephropathy | 20 (12.4) | 3 (4.35) | 17 (18.5) | 0.0075 |

| Tubulo-interstitial disease | 17 (10.6) | 8 (11.6) | 9 (9.8) | 0.80 |

| CAKUT | 12 (7.4) | 7 (10.1) | 5 (5.4) | 0.36 |

| Other | 6 (3.7) | 2 (2.9) | 4 (4.3) | 0.70 |

| Unknown | 14 (8.7) | 5 (7.25) | 9 (9.8) | 0.78 |

| Dialysis modality at waitlisting, n (%) | ||||

| Haemodialysis | 92 (57.1) | 17 (24.6) | 75 (81.5) | P < 0.001 |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 46 (28.6) | 29 (42.0) | 17 (18.5) | P < 0.001 |

| Not yet treated with dialysis | 23 (14.2) | 23 (33.3) | NA | |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 38 (23.6) | 11 (15.9) | 27 (29.3) | 0.05 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 38 (23.6) | 9 (13.0) | 29 (31.5) | 0.006 |

| Lung disease | 36 (22.4) | 12 (17.4) | 24 (26.1) | 0.19 |

| Liver disease | 8 (5.0) | 2 (2.9) | 6 (6.5) | 0.47 |

| Psychiatric disease | 25 (15.5) | 8 (11.6) | 17 (18.5) | 0.23 |

| Infection, (between the start of CKD stage 5 and registration on the waiting list) | 54 (33.5) | 17 (24.6) | 37 (40.2) | 0.057 |

| History of malignancy | 9 (5.6) | 2 (2.9) | 7 (7.6) | 0.30 |

| Hospitalization between start of CKD stage 5 and start of transplant workup (days), median (IQR) | 2 (0–11) | 0.00 (0-0) | 9.00 (2–20) | P < 0.001 |

| Psychosocial, n (%) | ||||

| Financial issues | 53 (32.9) | 16 (23.2) | 37 (40.2) | 0.023 |

| Insufficient health insurance | 12 (7.4) | 2 (2.9) | 10 (10.9) | 0.07 |

| Language difficulties | 44 (27.3) | 8 (11.6) | 36 (39.1) | P < 0.001 |

| Complete language barrier | 24 (14.9) | 5 (7.2) | 19 (20.6) | 0.024 |

| Non-adherence | 29 (18.0) | 9 (13.0) | 20 (21.7) | 0.15 |

| Timing of nephrology care | ||||

| Time between first nephrology contact and start of CKD stage 5 (months), median (IQR) | 41.2 (4.3–87) | 61.9 (26.8–133.6) | 20.9 (0–65.2) | P < 0.001 |

| Late referral, n (%) | 35 (21.7) | 5 (7.3) | 30 (32.6) | P < 0.001 |

| Start of workup before first access procedure, n (%) | 51 (31.7) | 51 (74.0) | NA | P < 0.001 |

| Time between start of CKD stage 5 and start of dialysis (months), median (IQR) | 4.8 (0.6–12) | 9.6 (3.4–13) | 2.7 (0.1–10.4) | P < 0.001 |

| Treating centre is renal transplant centre, n (%) | 36 (22.4) | 23 (33.3) | 13 (14.1) | 0.007 |

Descriptive statistics of the total population and the two subgroups (those who started the transplant workup before the start of dialysis and those who started after the start of dialysis). All percentages are column percentages. Univariate analysis P-values are presented. NA: not applicable.

| . | Total . | Start of transplant workup . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics . | Population (N = 161) . | Before start of dialysis (n = 69) . | After start of dialysis (n = 92) . | P-value . |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 53 (43–64) | 52 (39–61) | 53.5 (45–65) | 0.16 |

| Male, n (%) | 100 (62.1) | 35 (50.7) | 65 (70.7) | 0.01 |

| BMI (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 26.3 (23.4–29.5) | 25.7 (23–29) | 27 (24.5–30) | 0.065 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 14 (8.7) | 5 (7.2) | 9 (9.8) | 0.78 |

| Primary renal disease, n (%) | ||||

| ADPKD | 31 (19.2) | 22 (32.0) | 9 (9.8) | P < 0.001 |

| Diabetic nephropathy | 26 (16.15) | 8 (11.6) | 18 (19.6) | 0.17 |

| Glomerular disease | 35 (21.7) | 14 (20.3) | 21 (22.8) | 0.7 |

| Hypertensive nephropathy | 20 (12.4) | 3 (4.35) | 17 (18.5) | 0.0075 |

| Tubulo-interstitial disease | 17 (10.6) | 8 (11.6) | 9 (9.8) | 0.80 |

| CAKUT | 12 (7.4) | 7 (10.1) | 5 (5.4) | 0.36 |

| Other | 6 (3.7) | 2 (2.9) | 4 (4.3) | 0.70 |

| Unknown | 14 (8.7) | 5 (7.25) | 9 (9.8) | 0.78 |

| Dialysis modality at waitlisting, n (%) | ||||

| Haemodialysis | 92 (57.1) | 17 (24.6) | 75 (81.5) | P < 0.001 |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 46 (28.6) | 29 (42.0) | 17 (18.5) | P < 0.001 |

| Not yet treated with dialysis | 23 (14.2) | 23 (33.3) | NA | |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 38 (23.6) | 11 (15.9) | 27 (29.3) | 0.05 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 38 (23.6) | 9 (13.0) | 29 (31.5) | 0.006 |

| Lung disease | 36 (22.4) | 12 (17.4) | 24 (26.1) | 0.19 |

| Liver disease | 8 (5.0) | 2 (2.9) | 6 (6.5) | 0.47 |

| Psychiatric disease | 25 (15.5) | 8 (11.6) | 17 (18.5) | 0.23 |

| Infection, (between the start of CKD stage 5 and registration on the waiting list) | 54 (33.5) | 17 (24.6) | 37 (40.2) | 0.057 |

| History of malignancy | 9 (5.6) | 2 (2.9) | 7 (7.6) | 0.30 |

| Hospitalization between start of CKD stage 5 and start of transplant workup (days), median (IQR) | 2 (0–11) | 0.00 (0-0) | 9.00 (2–20) | P < 0.001 |

| Psychosocial, n (%) | ||||

| Financial issues | 53 (32.9) | 16 (23.2) | 37 (40.2) | 0.023 |

| Insufficient health insurance | 12 (7.4) | 2 (2.9) | 10 (10.9) | 0.07 |

| Language difficulties | 44 (27.3) | 8 (11.6) | 36 (39.1) | P < 0.001 |

| Complete language barrier | 24 (14.9) | 5 (7.2) | 19 (20.6) | 0.024 |

| Non-adherence | 29 (18.0) | 9 (13.0) | 20 (21.7) | 0.15 |

| Timing of nephrology care | ||||

| Time between first nephrology contact and start of CKD stage 5 (months), median (IQR) | 41.2 (4.3–87) | 61.9 (26.8–133.6) | 20.9 (0–65.2) | P < 0.001 |

| Late referral, n (%) | 35 (21.7) | 5 (7.3) | 30 (32.6) | P < 0.001 |

| Start of workup before first access procedure, n (%) | 51 (31.7) | 51 (74.0) | NA | P < 0.001 |

| Time between start of CKD stage 5 and start of dialysis (months), median (IQR) | 4.8 (0.6–12) | 9.6 (3.4–13) | 2.7 (0.1–10.4) | P < 0.001 |

| Treating centre is renal transplant centre, n (%) | 36 (22.4) | 23 (33.3) | 13 (14.1) | 0.007 |

| . | Total . | Start of transplant workup . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics . | Population (N = 161) . | Before start of dialysis (n = 69) . | After start of dialysis (n = 92) . | P-value . |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 53 (43–64) | 52 (39–61) | 53.5 (45–65) | 0.16 |

| Male, n (%) | 100 (62.1) | 35 (50.7) | 65 (70.7) | 0.01 |

| BMI (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 26.3 (23.4–29.5) | 25.7 (23–29) | 27 (24.5–30) | 0.065 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 14 (8.7) | 5 (7.2) | 9 (9.8) | 0.78 |

| Primary renal disease, n (%) | ||||

| ADPKD | 31 (19.2) | 22 (32.0) | 9 (9.8) | P < 0.001 |

| Diabetic nephropathy | 26 (16.15) | 8 (11.6) | 18 (19.6) | 0.17 |

| Glomerular disease | 35 (21.7) | 14 (20.3) | 21 (22.8) | 0.7 |

| Hypertensive nephropathy | 20 (12.4) | 3 (4.35) | 17 (18.5) | 0.0075 |

| Tubulo-interstitial disease | 17 (10.6) | 8 (11.6) | 9 (9.8) | 0.80 |

| CAKUT | 12 (7.4) | 7 (10.1) | 5 (5.4) | 0.36 |

| Other | 6 (3.7) | 2 (2.9) | 4 (4.3) | 0.70 |

| Unknown | 14 (8.7) | 5 (7.25) | 9 (9.8) | 0.78 |

| Dialysis modality at waitlisting, n (%) | ||||

| Haemodialysis | 92 (57.1) | 17 (24.6) | 75 (81.5) | P < 0.001 |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 46 (28.6) | 29 (42.0) | 17 (18.5) | P < 0.001 |

| Not yet treated with dialysis | 23 (14.2) | 23 (33.3) | NA | |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 38 (23.6) | 11 (15.9) | 27 (29.3) | 0.05 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 38 (23.6) | 9 (13.0) | 29 (31.5) | 0.006 |

| Lung disease | 36 (22.4) | 12 (17.4) | 24 (26.1) | 0.19 |

| Liver disease | 8 (5.0) | 2 (2.9) | 6 (6.5) | 0.47 |

| Psychiatric disease | 25 (15.5) | 8 (11.6) | 17 (18.5) | 0.23 |

| Infection, (between the start of CKD stage 5 and registration on the waiting list) | 54 (33.5) | 17 (24.6) | 37 (40.2) | 0.057 |

| History of malignancy | 9 (5.6) | 2 (2.9) | 7 (7.6) | 0.30 |

| Hospitalization between start of CKD stage 5 and start of transplant workup (days), median (IQR) | 2 (0–11) | 0.00 (0-0) | 9.00 (2–20) | P < 0.001 |

| Psychosocial, n (%) | ||||

| Financial issues | 53 (32.9) | 16 (23.2) | 37 (40.2) | 0.023 |

| Insufficient health insurance | 12 (7.4) | 2 (2.9) | 10 (10.9) | 0.07 |

| Language difficulties | 44 (27.3) | 8 (11.6) | 36 (39.1) | P < 0.001 |

| Complete language barrier | 24 (14.9) | 5 (7.2) | 19 (20.6) | 0.024 |

| Non-adherence | 29 (18.0) | 9 (13.0) | 20 (21.7) | 0.15 |

| Timing of nephrology care | ||||

| Time between first nephrology contact and start of CKD stage 5 (months), median (IQR) | 41.2 (4.3–87) | 61.9 (26.8–133.6) | 20.9 (0–65.2) | P < 0.001 |

| Late referral, n (%) | 35 (21.7) | 5 (7.3) | 30 (32.6) | P < 0.001 |

| Start of workup before first access procedure, n (%) | 51 (31.7) | 51 (74.0) | NA | P < 0.001 |

| Time between start of CKD stage 5 and start of dialysis (months), median (IQR) | 4.8 (0.6–12) | 9.6 (3.4–13) | 2.7 (0.1–10.4) | P < 0.001 |

| Treating centre is renal transplant centre, n (%) | 36 (22.4) | 23 (33.3) | 13 (14.1) | 0.007 |

Descriptive statistics of the total population and the two subgroups (those who started the transplant workup before the start of dialysis and those who started after the start of dialysis). All percentages are column percentages. Univariate analysis P-values are presented. NA: not applicable.

As for non-medical factors, having some degree of language barrier or financial struggle was more frequent in the group of patients who started the workup after dialysis [39 versus 12% (P < 0.001) and 40 versus 23% (P = 0.023), respectively]. They also had a significantly shorter time in nephrology care prior to CKD stage 5 (21 versus 62 months; P < 0.001) and were more often late referrals (33 versus 7%; P < 0.001). The time interval between the start of CKD stage 5 and the start of dialysis was significantly shorter (3 versus 10 months; P < 0.001), but this difference lost statistical significance after the exclusion of late referrals (data not shown). Furthermore, patients were less likely to start their transplant workup before starting dialysis when they were cared for in one of the referring centres instead of the transplant centre (14 versus 33%; P = 0.007).

Multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the relative impact of different patient-derived factors on the likelihood of starting the transplant workup before the start of dialysis (Table 2). Three variables appear to make a statistically significant contribution to the model. The most important predictor was the number of hospitalization days, with an odds ratio of 0.79 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.69–0.89]. Patients with language difficulties were also less likely to pre-emptively start their pre-transplant workup [odds ratio (OR) 0.20 (95% CI 0.06–0.61)]. The amount of time spent in nephrology care before the start of CKD stage 5 was the third contributor, with an OR of 1.01 (95% CI 1.00–1.02).

| . | . | 95% CI . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables . | OR . | Lower . | Upper . | P-value . |

| Age at registration on waiting list | 1.0 | 0.97 | 1.04 | 0.979 |

| Sex (1 = male) | 0.42 | 0.16 | 1.05 | 0.063 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 0.44 | 0.13 | 1.46 | 0.179 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.53 | 0.17 | 1.68 | 0.277 |

| Language difficulties | 0.20 | 0.06 | 0.61 | 0.005 |

| Months between first nephrology contact and CKD 5 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 0.034 |

| Hospitalization days between CKD 5 and start workup | 0.79 | 0.69 | 0.89 | <0.001 |

| . | . | 95% CI . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables . | OR . | Lower . | Upper . | P-value . |

| Age at registration on waiting list | 1.0 | 0.97 | 1.04 | 0.979 |

| Sex (1 = male) | 0.42 | 0.16 | 1.05 | 0.063 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 0.44 | 0.13 | 1.46 | 0.179 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.53 | 0.17 | 1.68 | 0.277 |

| Language difficulties | 0.20 | 0.06 | 0.61 | 0.005 |

| Months between first nephrology contact and CKD 5 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 0.034 |

| Hospitalization days between CKD 5 and start workup | 0.79 | 0.69 | 0.89 | <0.001 |

Multiple logistic regression model predicting the likelihood of starting the transplant workup before the start of dialysis (dependent variable = starting the transplant workup before starting dialysis). The model classified 81% of cases correctly. The Nagelkerke pseudo-R2 was 59%.

| . | . | 95% CI . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables . | OR . | Lower . | Upper . | P-value . |

| Age at registration on waiting list | 1.0 | 0.97 | 1.04 | 0.979 |

| Sex (1 = male) | 0.42 | 0.16 | 1.05 | 0.063 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 0.44 | 0.13 | 1.46 | 0.179 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.53 | 0.17 | 1.68 | 0.277 |

| Language difficulties | 0.20 | 0.06 | 0.61 | 0.005 |

| Months between first nephrology contact and CKD 5 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 0.034 |

| Hospitalization days between CKD 5 and start workup | 0.79 | 0.69 | 0.89 | <0.001 |

| . | . | 95% CI . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables . | OR . | Lower . | Upper . | P-value . |

| Age at registration on waiting list | 1.0 | 0.97 | 1.04 | 0.979 |

| Sex (1 = male) | 0.42 | 0.16 | 1.05 | 0.063 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 0.44 | 0.13 | 1.46 | 0.179 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.53 | 0.17 | 1.68 | 0.277 |

| Language difficulties | 0.20 | 0.06 | 0.61 | 0.005 |

| Months between first nephrology contact and CKD 5 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 0.034 |

| Hospitalization days between CKD 5 and start workup | 0.79 | 0.69 | 0.89 | <0.001 |

Multiple logistic regression model predicting the likelihood of starting the transplant workup before the start of dialysis (dependent variable = starting the transplant workup before starting dialysis). The model classified 81% of cases correctly. The Nagelkerke pseudo-R2 was 59%.

Duration of the transplant workup

After starting the transplant workup, it took a median of 8.6 months [interquartile range (IQR) 5–14] to finalize the workup and be registered on the waiting list. There was no significant difference between the patients who started the transplant evaluation before or after starting dialysis, with a median duration of 10 versus 8 months (P = 0.46) (Table 3).

Descriptive statistics of the workup time in the total population and certain subpopulations

| Variables . | Screening time (months), median (IQR) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|

| Total population (N = 160) | 8.6 (5–14) | |

| Excluding pre-emptive waitlisting (n = 137) | 8.7 (5–14) | |

| Excluding cardiovascular disease, diabetes, infections and >5 hospitalization days during the workup period (n = 58) | 7.2 (4–11.6) | |

| Timing of the transplant workup | ||

| Before start of dialysis (n = 69) | 10 (5–15) | 0.46 |

| After start of dialysis (n = 91) | 8 (5–14) | |

| Transplant centre | ||

| Transplant centre (n = 36) | 10 (6–19) | 0.211 |

| Non-transplant centre (n = 124) | 8.3 (5–13.4) |

| Variables . | Screening time (months), median (IQR) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|

| Total population (N = 160) | 8.6 (5–14) | |

| Excluding pre-emptive waitlisting (n = 137) | 8.7 (5–14) | |

| Excluding cardiovascular disease, diabetes, infections and >5 hospitalization days during the workup period (n = 58) | 7.2 (4–11.6) | |

| Timing of the transplant workup | ||

| Before start of dialysis (n = 69) | 10 (5–15) | 0.46 |

| After start of dialysis (n = 91) | 8 (5–14) | |

| Transplant centre | ||

| Transplant centre (n = 36) | 10 (6–19) | 0.211 |

| Non-transplant centre (n = 124) | 8.3 (5–13.4) |

Workup time is calculated as the time between the start of workup and the ultimate registration on the waiting list.

Descriptive statistics of the workup time in the total population and certain subpopulations

| Variables . | Screening time (months), median (IQR) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|

| Total population (N = 160) | 8.6 (5–14) | |

| Excluding pre-emptive waitlisting (n = 137) | 8.7 (5–14) | |

| Excluding cardiovascular disease, diabetes, infections and >5 hospitalization days during the workup period (n = 58) | 7.2 (4–11.6) | |

| Timing of the transplant workup | ||

| Before start of dialysis (n = 69) | 10 (5–15) | 0.46 |

| After start of dialysis (n = 91) | 8 (5–14) | |

| Transplant centre | ||

| Transplant centre (n = 36) | 10 (6–19) | 0.211 |

| Non-transplant centre (n = 124) | 8.3 (5–13.4) |

| Variables . | Screening time (months), median (IQR) . | P-value . |

|---|---|---|

| Total population (N = 160) | 8.6 (5–14) | |

| Excluding pre-emptive waitlisting (n = 137) | 8.7 (5–14) | |

| Excluding cardiovascular disease, diabetes, infections and >5 hospitalization days during the workup period (n = 58) | 7.2 (4–11.6) | |

| Timing of the transplant workup | ||

| Before start of dialysis (n = 69) | 10 (5–15) | 0.46 |

| After start of dialysis (n = 91) | 8 (5–14) | |

| Transplant centre | ||

| Transplant centre (n = 36) | 10 (6–19) | 0.211 |

| Non-transplant centre (n = 124) | 8.3 (5–13.4) |

Workup time is calculated as the time between the start of workup and the ultimate registration on the waiting list.

For the patients who started the workup after they started dialysis (n = 91), there was a median delay of 4.2 months (IQR 1.6–12) between the start of dialysis and the start of the transplant evaluation. This additional delay led to a median of 11.2 months (IQR 5.7–19.8) spent on dialysis before being registered on the transplant waiting list (n = 138, after the exclusion of the 23 patients who were registered prior to the start of dialysis) with a significant difference between the patients who started the transplant evaluation before versus after dialysis [4.6 months (IQR 2.3–10.9) versus 15.4 months (IQR 8.7–25.2); P < 0.001].

Because the workup time might have been artificially prolonged in the patients who were pre-emptively waitlisted (because the physician had more time), a separate analysis was performed after the exclusion of these patients, but this failed to show any improvement (Table 3). Furthermore, when selecting the ‘healthiest’ subgroup of patients (i.e. without cardiovascular disease, diabetes or infections and with a maximum of 5 hospitalization days during the workup period), the median workup time was only marginally shorter. There was no significant difference in time spent on the transplant evaluation between patients cared for in the transplant centre versus the referring centres.

A total of 31% of patients had at least one extra medical examination beyond the recommended workup that had no clear medical indication traceable in the patient file. This was predominantly the case for gastroscopy and ultrasound of the carotid arteries (Table 4).

| Examinations . | Total (N = 161) . | Clear indication . | No clear indication . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Invasive urologic examination, n (%) | 45 (28) | 30 (67) | 15 (33) |

| Gastroscopy, n (%) | 88 (55) | 55 (63) | 33 (38) |

| Colonoscopy, n (%) | 109 (68) | 105 (96) | 4 (4) |

| Ultrasound of the carotid arteries, n (%) | 14 (9) | 5 (36) | 9 (64) |

| At least one examination without clear indication, n (%) | 50 (31) |

| Examinations . | Total (N = 161) . | Clear indication . | No clear indication . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Invasive urologic examination, n (%) | 45 (28) | 30 (67) | 15 (33) |

| Gastroscopy, n (%) | 88 (55) | 55 (63) | 33 (38) |

| Colonoscopy, n (%) | 109 (68) | 105 (96) | 4 (4) |

| Ultrasound of the carotid arteries, n (%) | 14 (9) | 5 (36) | 9 (64) |

| At least one examination without clear indication, n (%) | 50 (31) |

Frequency of certain pre-transplant examinations and whether or not a clear indication was found (medical or based on screening guidelines [20]). First column: percentages of total; second and third column: percentages of value in first column (horizontal percentage).

| Examinations . | Total (N = 161) . | Clear indication . | No clear indication . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Invasive urologic examination, n (%) | 45 (28) | 30 (67) | 15 (33) |

| Gastroscopy, n (%) | 88 (55) | 55 (63) | 33 (38) |

| Colonoscopy, n (%) | 109 (68) | 105 (96) | 4 (4) |

| Ultrasound of the carotid arteries, n (%) | 14 (9) | 5 (36) | 9 (64) |

| At least one examination without clear indication, n (%) | 50 (31) |

| Examinations . | Total (N = 161) . | Clear indication . | No clear indication . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Invasive urologic examination, n (%) | 45 (28) | 30 (67) | 15 (33) |

| Gastroscopy, n (%) | 88 (55) | 55 (63) | 33 (38) |

| Colonoscopy, n (%) | 109 (68) | 105 (96) | 4 (4) |

| Ultrasound of the carotid arteries, n (%) | 14 (9) | 5 (36) | 9 (64) |

| At least one examination without clear indication, n (%) | 50 (31) |

Frequency of certain pre-transplant examinations and whether or not a clear indication was found (medical or based on screening guidelines [20]). First column: percentages of total; second and third column: percentages of value in first column (horizontal percentage).

After multiple linear regression analysis, only the number of hospitalization days appeared significantly related to the time needed to complete the transplant workup (Table 5). However, this model explained only 16% of the total variance in the time spent on the transplant workup, indicating that other unknown factors probably play a major role in its delay.

| . | Simple linear regression . | Multiple linear regression . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables . | B . | SE . | P-value . | Exp(B) . | B . | SE . | Beta . | P-value . | Exp(B) . |

| Age | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.436 | 1.0 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.058 | 0.467 | 1.0 |

| Sex (1 = male) | 0.063 | 0.050 | 0.204 | 1.16 | 0.062 | 0.050 | 0.099 | 0.219 | 1.15 |

| Body mass index | 0.010 | 0.006 | 0.092 | 1.02 | |||||

| Comorbidities | |||||||||

| Cardiovascular disease | 0.040 | 0.057 | 0.480 | 1.1 | |||||

| Diabetes mellitus | –0.011 | 0.057 | 0.845 | 0.97 | |||||

| Lung disease | 0.119 | 0.057 | 0.041 | 1.32 | 0.087 | 0.055 | 0.119 | 0.120 | 1.22 |

| Liver disease | 0.180 | 0.110 | 0.105 | 1.51 | |||||

| History of malignancy | –0.170 | 0.104 | 0.105 | 0.68 | |||||

| Psychiatric disease | 0.014 | 0.067 | 0.840 | 1.03 | |||||

| Infection between start of CKD stage 5 and registration on the waiting list | 0.153 | 0.050 | 0.003 | 1.42 | 0.087 | 0.051 | 0.134 | 0.090 | 1.22 |

| Non-adherence | 0.073 | 0.063 | 0.247 | 1.18 | |||||

| Language difficulties | 0.057 | 0.054 | 0.295 | 1.14 | |||||

| Financial issues | 0.095 | 0.051 | 0.066 | 1.24 | |||||

| Number of extra exams | 0.034 | 0.024 | 0.157 | 1.08 | |||||

| Hospitalization days between start of workup and registration | 0.015 | 0.003 | <0.001 | 1.04 | 0.013 | 0.004 | 0.300 | <0.001 | 1.03 |

| Haemodialysis (versus PD or not yet on dialysis) | 0.037 | 0.050 | 0.465 | 1.09 | |||||

| . | Simple linear regression . | Multiple linear regression . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables . | B . | SE . | P-value . | Exp(B) . | B . | SE . | Beta . | P-value . | Exp(B) . |

| Age | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.436 | 1.0 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.058 | 0.467 | 1.0 |

| Sex (1 = male) | 0.063 | 0.050 | 0.204 | 1.16 | 0.062 | 0.050 | 0.099 | 0.219 | 1.15 |

| Body mass index | 0.010 | 0.006 | 0.092 | 1.02 | |||||

| Comorbidities | |||||||||

| Cardiovascular disease | 0.040 | 0.057 | 0.480 | 1.1 | |||||

| Diabetes mellitus | –0.011 | 0.057 | 0.845 | 0.97 | |||||

| Lung disease | 0.119 | 0.057 | 0.041 | 1.32 | 0.087 | 0.055 | 0.119 | 0.120 | 1.22 |

| Liver disease | 0.180 | 0.110 | 0.105 | 1.51 | |||||

| History of malignancy | –0.170 | 0.104 | 0.105 | 0.68 | |||||

| Psychiatric disease | 0.014 | 0.067 | 0.840 | 1.03 | |||||

| Infection between start of CKD stage 5 and registration on the waiting list | 0.153 | 0.050 | 0.003 | 1.42 | 0.087 | 0.051 | 0.134 | 0.090 | 1.22 |

| Non-adherence | 0.073 | 0.063 | 0.247 | 1.18 | |||||

| Language difficulties | 0.057 | 0.054 | 0.295 | 1.14 | |||||

| Financial issues | 0.095 | 0.051 | 0.066 | 1.24 | |||||

| Number of extra exams | 0.034 | 0.024 | 0.157 | 1.08 | |||||

| Hospitalization days between start of workup and registration | 0.015 | 0.003 | <0.001 | 1.04 | 0.013 | 0.004 | 0.300 | <0.001 | 1.03 |

| Haemodialysis (versus PD or not yet on dialysis) | 0.037 | 0.050 | 0.465 | 1.09 | |||||

Simple and multiple regression analysis for a variety of patient-derived independent variables and the logarithmically transformed workup time. Our multiple regression model included sex, age, infections, hospitalization days and lung disease and explained 16.5% of the total variance in workup time [F (5,151) = 5.962, P < 0.001]. After conversion of the logarithmic scale to the original time value, we can conclude that for every extra hospitalization day, the workup time increased with 3% or 0.9 days. B: unstandardized regression coefficient; SE: standard error; Exp(B): exponentiation of B (10B) to reverse the logarithmic scale into the original time measured in months.

| . | Simple linear regression . | Multiple linear regression . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables . | B . | SE . | P-value . | Exp(B) . | B . | SE . | Beta . | P-value . | Exp(B) . |

| Age | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.436 | 1.0 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.058 | 0.467 | 1.0 |

| Sex (1 = male) | 0.063 | 0.050 | 0.204 | 1.16 | 0.062 | 0.050 | 0.099 | 0.219 | 1.15 |

| Body mass index | 0.010 | 0.006 | 0.092 | 1.02 | |||||

| Comorbidities | |||||||||

| Cardiovascular disease | 0.040 | 0.057 | 0.480 | 1.1 | |||||

| Diabetes mellitus | –0.011 | 0.057 | 0.845 | 0.97 | |||||

| Lung disease | 0.119 | 0.057 | 0.041 | 1.32 | 0.087 | 0.055 | 0.119 | 0.120 | 1.22 |

| Liver disease | 0.180 | 0.110 | 0.105 | 1.51 | |||||

| History of malignancy | –0.170 | 0.104 | 0.105 | 0.68 | |||||

| Psychiatric disease | 0.014 | 0.067 | 0.840 | 1.03 | |||||

| Infection between start of CKD stage 5 and registration on the waiting list | 0.153 | 0.050 | 0.003 | 1.42 | 0.087 | 0.051 | 0.134 | 0.090 | 1.22 |

| Non-adherence | 0.073 | 0.063 | 0.247 | 1.18 | |||||

| Language difficulties | 0.057 | 0.054 | 0.295 | 1.14 | |||||

| Financial issues | 0.095 | 0.051 | 0.066 | 1.24 | |||||

| Number of extra exams | 0.034 | 0.024 | 0.157 | 1.08 | |||||

| Hospitalization days between start of workup and registration | 0.015 | 0.003 | <0.001 | 1.04 | 0.013 | 0.004 | 0.300 | <0.001 | 1.03 |

| Haemodialysis (versus PD or not yet on dialysis) | 0.037 | 0.050 | 0.465 | 1.09 | |||||

| . | Simple linear regression . | Multiple linear regression . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables . | B . | SE . | P-value . | Exp(B) . | B . | SE . | Beta . | P-value . | Exp(B) . |

| Age | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.436 | 1.0 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.058 | 0.467 | 1.0 |

| Sex (1 = male) | 0.063 | 0.050 | 0.204 | 1.16 | 0.062 | 0.050 | 0.099 | 0.219 | 1.15 |

| Body mass index | 0.010 | 0.006 | 0.092 | 1.02 | |||||

| Comorbidities | |||||||||

| Cardiovascular disease | 0.040 | 0.057 | 0.480 | 1.1 | |||||

| Diabetes mellitus | –0.011 | 0.057 | 0.845 | 0.97 | |||||

| Lung disease | 0.119 | 0.057 | 0.041 | 1.32 | 0.087 | 0.055 | 0.119 | 0.120 | 1.22 |

| Liver disease | 0.180 | 0.110 | 0.105 | 1.51 | |||||

| History of malignancy | –0.170 | 0.104 | 0.105 | 0.68 | |||||

| Psychiatric disease | 0.014 | 0.067 | 0.840 | 1.03 | |||||

| Infection between start of CKD stage 5 and registration on the waiting list | 0.153 | 0.050 | 0.003 | 1.42 | 0.087 | 0.051 | 0.134 | 0.090 | 1.22 |

| Non-adherence | 0.073 | 0.063 | 0.247 | 1.18 | |||||

| Language difficulties | 0.057 | 0.054 | 0.295 | 1.14 | |||||

| Financial issues | 0.095 | 0.051 | 0.066 | 1.24 | |||||

| Number of extra exams | 0.034 | 0.024 | 0.157 | 1.08 | |||||

| Hospitalization days between start of workup and registration | 0.015 | 0.003 | <0.001 | 1.04 | 0.013 | 0.004 | 0.300 | <0.001 | 1.03 |

| Haemodialysis (versus PD or not yet on dialysis) | 0.037 | 0.050 | 0.465 | 1.09 | |||||

Simple and multiple regression analysis for a variety of patient-derived independent variables and the logarithmically transformed workup time. Our multiple regression model included sex, age, infections, hospitalization days and lung disease and explained 16.5% of the total variance in workup time [F (5,151) = 5.962, P < 0.001]. After conversion of the logarithmic scale to the original time value, we can conclude that for every extra hospitalization day, the workup time increased with 3% or 0.9 days. B: unstandardized regression coefficient; SE: standard error; Exp(B): exponentiation of B (10B) to reverse the logarithmic scale into the original time measured in months.

DISCUSSION

We performed an in-depth retrospective analysis of the chronology of actions taken during the care of transplant-eligible patients with renal failure in our centre and our network of referring hospitals in Antwerp, Belgium. Our key conclusion is that less than half (43%) of patients started the transplant evaluation before dialysis initiation and only 14% were pre-emptively waitlisted. These findings are comparable to reports from the USA and Europe. In a single-centre analysis from the USA analysing data from 2004 to 2007 (n = 695), Waterman et al. [19] observed that 60–83% of patients had been on dialysis for ≥2 years at the time of presentation for transplant evaluation. In a multicentre analysis of all transplant centres in Georgia, USA (n = 1580), Gander et al. [15] observed that only 20% of referrals for transplant evaluation were pre-emptive referrals. Data from Europe concerning the rate of pre-emptive registration are also in line with our findings, ranging from 6% in the 2018 French Renal Epidemiology and Information Network registry report [21], to 7.3% in the 2016 Eurotransplant annual report [22] to 26% in the French North West Local Health Integration Network from 2008 to 2012 [17].

Multivariable analysis identified three variables that were significantly associated with a delayed start of the transplant workup (i.e. after dialysis initiation), which could be addressed to some extent (Table 6). The most important risk factor was the number of hospitalization days from CKD stage 5 to the start of screening, probably representing poorer general health. Medical complications are frequent and not always preventable in patients with kidney failure. Nevertheless, prompt initiation of the workup should be encouraged even in more vulnerable patients, because complications tend to accumulate with time spent on dialysis. The second risk factor was the presence of a language barrier. Informing and preparing patients for dialysis and transplantation requires extensive patient-tailored communication and is obviously more challenging in the case of a language difference. Particularly in this setting, early information on transplantation, preferably before or together with dialysis preparation, could promote timely waitlisting. The third risk factor for a delayed start of the transplant workup was a shorter duration of pre-CKD stage 5 nephrology care. This was mainly driven by late referrals. Although this subgroup is difficult to target with preventive measures, extra efforts should aim at minimizing the time between dialysis initiation and the start of the transplant workup [16, 23, 24].

A summary of the variables that were independently associated with a delayed start of the workup or a prolonged workup

| . | Modifiable? . | Suggested actions . |

|---|---|---|

| Variables delaying the start of the workup | ||

| Language difficulties | Yes | Stimulate patients to learn the local language Have interpreters readily available during the pre-transplant process Use technological tools providing accessible multilingual education |

| Months between first nephrology contact and start of CKD stage 5 | No | Timely referral of CKD patients to the nephrologist as according to published guidelines [37] |

| Hospitalization days between start of CKD stage 5 and start of the workup | No | Timely start of the transplant workup (minimum of 6 months before estimated start of dialysis) to avoid delay of workup initiation due to kidney failure–related complications |

| Variables prolonging the workup | ||

| Hospitalization days between start of workup and registration | No | Timely start of the transplant workup to avoid prolonging the workup duration due to kidney failure–related complications |

| . | Modifiable? . | Suggested actions . |

|---|---|---|

| Variables delaying the start of the workup | ||

| Language difficulties | Yes | Stimulate patients to learn the local language Have interpreters readily available during the pre-transplant process Use technological tools providing accessible multilingual education |

| Months between first nephrology contact and start of CKD stage 5 | No | Timely referral of CKD patients to the nephrologist as according to published guidelines [37] |

| Hospitalization days between start of CKD stage 5 and start of the workup | No | Timely start of the transplant workup (minimum of 6 months before estimated start of dialysis) to avoid delay of workup initiation due to kidney failure–related complications |

| Variables prolonging the workup | ||

| Hospitalization days between start of workup and registration | No | Timely start of the transplant workup to avoid prolonging the workup duration due to kidney failure–related complications |

A summary of the variables that were independently associated with a delayed start of the workup or a prolonged workup

| . | Modifiable? . | Suggested actions . |

|---|---|---|

| Variables delaying the start of the workup | ||

| Language difficulties | Yes | Stimulate patients to learn the local language Have interpreters readily available during the pre-transplant process Use technological tools providing accessible multilingual education |

| Months between first nephrology contact and start of CKD stage 5 | No | Timely referral of CKD patients to the nephrologist as according to published guidelines [37] |

| Hospitalization days between start of CKD stage 5 and start of the workup | No | Timely start of the transplant workup (minimum of 6 months before estimated start of dialysis) to avoid delay of workup initiation due to kidney failure–related complications |

| Variables prolonging the workup | ||

| Hospitalization days between start of workup and registration | No | Timely start of the transplant workup to avoid prolonging the workup duration due to kidney failure–related complications |

| . | Modifiable? . | Suggested actions . |

|---|---|---|

| Variables delaying the start of the workup | ||

| Language difficulties | Yes | Stimulate patients to learn the local language Have interpreters readily available during the pre-transplant process Use technological tools providing accessible multilingual education |

| Months between first nephrology contact and start of CKD stage 5 | No | Timely referral of CKD patients to the nephrologist as according to published guidelines [37] |

| Hospitalization days between start of CKD stage 5 and start of the workup | No | Timely start of the transplant workup (minimum of 6 months before estimated start of dialysis) to avoid delay of workup initiation due to kidney failure–related complications |

| Variables prolonging the workup | ||

| Hospitalization days between start of workup and registration | No | Timely start of the transplant workup to avoid prolonging the workup duration due to kidney failure–related complications |

Studies addressing the timing of the transplant evaluation are scarce. A French study on 1725 patients that started renal replacement therapy between 1997 and 2003 in the region of Lorraine identified only older age and treatment in a centre that does not perform renal transplantation as significant factors reducing the likelihood of being waitlisted before the start of dialysis [25]. The difference in identified risk factors illustrates the between-centre variability in pre-transplant care and highlights the importance for every centre to audit its own performance.

We observed a median duration of 8.6 months between the start of the transplant workup and registration on the waiting list, which is similar when compared with the limited data available. Single-centre data from France (n = 50) from 2013 to 2014 reported a median of 8.1 ± 4.7 months to complete the transplant evaluation [26], and in a 2015 study from the USA, Monson et al. [27] observed that 23.4% of patients did not complete the transplant workup within 1 year after their first pre-transplant visit.

In our study, the time spent on the transplant workup did not differ between patients who started the transplant evaluation before versus after the start of dialysis. However, we observed an additional median delay of 4.2 months between the start of dialysis and the start of the transplant workup in the last group. This had a dramatic impact on the total waiting time spent on dialysis before being waitlisted (15.4 versus 4.6 months). The delay between the start of dialysis and the start of the transplant workup could have had many potential explanations, such as access-related complications, late referrals and hope of recovery of renal function, among many others. However, it is significantly shorter than the time observed in the southeastern USA by Patzer et al. [16], who observed a median delay of 245 days, or 8 months, between the start of dialysis and referral for transplant evaluation in 11 862 incident dialysis patients between 2016 and 2018.

Despite our elaborate collection of medical and socio-economic variables, multivariable analysis could only identify the number of hospitalization days as a significantly prolonging factor of the time needed to finalize the transplant workup. Monson et al. [27] performed a similar analysis in 256 patients referred for transplant evaluation between 2009 and 2010 in the University Hospital of Chicago and observed that needing more than one hospitalization was associated with slower rates of transplant evaluation completion. Contrary to our findings, they observed that needing a large number of medical tests was associated with longer completion times. Our model could only explain 16% of the total variance in the time spent on the transplant workup. We therefore presume that significant time is lost during the workup period without a clear explanation and that there is room for improvement. Furthermore, the observation that excellent transplant candidates without comorbidities still need a median of 7 months to perform a minimal workup suggests that the physician's role is considerable. It is likely that physicians’ and patients’ inertia and administrative, practical and logistic hurdles all combine to prolong the duration of the transplant workup beyond reasonable limits for many patients.

Our study provides a detailed analysis of the timing and duration of the transplant workup. Nevertheless, it has several limitations. First, due to the limited sample size, our analysis is prone to overestimation of the differences between groups and our regression models risk overfitting of the data. It is possible that other variables that are known to be associated with decreased access to renal transplantation, notably comorbidities such as lung disease [28, 29], cardiovascular disease [16, 28] or diabetes [16, 28], might gain significance in a larger sample. Second, despite our elaborate collection of variables, we lacked several items that could also have influenced the delay in the transplant workup (e.g. the time lost on prerequisites such as smoking cessation or the waiting times for different screening examinations in the various hospitals, among many others). Third, despite the fact that our population was similar to other large transplant registries with regard to comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes and intercurrent infections [30], it provides a very detailed insight into only Belgian nephrology care and might not be generalizable. In fact, the workup time probably even varied between the 16 centres involved in this study, as illustrated by the observation that the workup was more often started before dialysis in the academic centre than in the referring centres. However, our cohort was too small to perform an intercentre comparative statistical analysis. Nevertheless, all centres used a guidance document provided by the academic centre in order to harmonize the workup between centres and avoid unnecessary examinations as much as possible.

We conclude that despite international recommendations, patients often start the transplant evaluation too late and the workup takes a relatively long time to finish. We presume that room for improvement exists at all different levels in pre-transplant renal care (Table 6). Education about transplantation, prior to or simultaneously with preparation for dialysis, should be a top priority to promote pre-emptive (living-donor) kidney transplantation and to minimize the time spent on dialysis waiting for a deceased-donor kidney transplantation. Innovative research has been done regarding more engaging and effective ways of patient education [31]. Technological tools providing accessible multilingual education and the organization of a specific CKD stage 5 clinic may also be of interest [26]. Implementation of an external quality control measure assessing centre-specific transplant education [32] and referral rates [33] has also been proposed, together with modifications of payment strategies for dialysis facilities [34, 35].

The transplant workup should also be limited to the recommended guidelines, and extra examinations should only be performed if there is a clear clinical indication. A recent European Renal Association–European Dialysis and Transplant Association expert opinion paper suggests restricting the transplant workup even further for younger patients (<40 years old) without comorbidities [36].

We would also like to stress that the objective to register patients pre-emptively or, at the latest, at the start of dialysis is not a futile action. Although it is true that time on dialysis is an important factor affecting an individual's ranking on the waiting list for deceased donor transplantation, and hence his or her chance to be transplanted, there is still a significant chance of being pre-emptively transplanted. Indeed, data from the 2016 Eurotransplant annual report show that 7% of patients were pre-emptively registered and 4.3% of patients were pre-emptively transplanted with a deceased donor [22]. These statistics are consistent across the years, which means that ∼30–50% of the pre-emptively registered patients also received a deceased-donor kidney pre-emptively. In other words, striving for pre-emptive registration has clear advantages for our patients and is not outweighed by the impact of waiting time on a patient's ranking on the waiting list.

In summary, we feel that analysing the timing of the start and duration of the transplant workup could be of value for every transplant centre and that these data should be collected in national or international registries in order to further improve the care we give to our patients with renal failure.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data underlying this article will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The results presented in this article have not been published previously in whole or part, except in abstract format.

Comments