-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Nestor Oliva-Damaso, Andrew S Bomback, Proposal for a more practical classification of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis, Clinical Kidney Journal, Volume 14, Issue 5, May 2021, Pages 1327–1334, https://doi.org/10.1093/ckj/sfaa255

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The nomenclature for antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated kidney disease has evolved from honorific eponyms to a descriptive-based classification scheme (Chapel Hill Consensus Conference 2012). Microscopic polyangiitis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis do not correlate with presentation, response rates and relapse rates as when comparing myeloperoxidase versus leukocyte proteinase 3. Here we discuss the limitations of the currently used classification and propose an alternative, simple classification according to (i) ANCA type and (ii) organ involvement, which provides important clinical information of prognosis and outcomes.

INTRODUCTION

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitides (AAV) are a group of clinical entities characterized by necrotizing inflammation of small- and medium-sized blood vessels due to inflammatory cell infiltration directed against two main antigenic targets: myeloperoxidase (MPO) and leukocyte proteinase 3 (PR3) [1, 2]. The 2012 Chapel Hill Consensus Conference (CHCC 2012) Nomenclature of Vasculitides defines AAV as necrotizing vasculitis, with few or no immune deposits, predominantly affecting small vessels (i.e. capillaries, venules, arterioles and small arteries) [3]. There have been several attempts to standardize the nomenclature and classify AAV, highlighting this difficult task [3–6], and studies have been designed to improve and update the classification criteria for primary systemic vasculitides [e.g. the Diagnostic and Classification Criteria in Vasculitis Study (DCVAS)] [7].

In the last decade, the nomenclature of AAV has changed from honorific eponyms to descriptive disease and aetiology-based names [8–10]. The AAV is now most commonly divided into renal-limited vasculitis (RLV), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) [3, 11]. This classification of AAV was defined at the CHCC 2012 (Table 1) and does not account for the presence of MPO versus PR3 autoantibodies. Because clinical outcomes (remission and relapse) have been shown to associate with ANCA subtype (MPO versus PR3) more reliably than with AAV nomenclature (e.g. MPA versus GPA), it has been suggested that AAV should be classified according to ANCA specificity (MPO or PR3) [12, 13], rather than by the CHCC 2012 scheme. In this review, we will summarize the limitations of the currently used classification of AAV and propose an alternative, simple classification according to (i) ANCA type and (ii) organ involvement.

Current clinico-pathological classification scheme modified from CHCC 2012 with categories of AAV [3]

| CHCC 2012 name . | CHCC 2012 definition . |

|---|---|

| RLV | Glomerulonephritis with no involvement of other organs |

| MPA | Injury to blood vessels in multiple tissues at the same time, such as kidneys, skin, nerves and lungs |

| GPA | The vasculitis is accompanied by granulomatous inflammation: often affects the lung, sinuses, nose, eyes or ears |

| EGPA | Granulomatous polyangiitis and the patient also has asthma + eosinophilia |

| CHCC 2012 name . | CHCC 2012 definition . |

|---|---|

| RLV | Glomerulonephritis with no involvement of other organs |

| MPA | Injury to blood vessels in multiple tissues at the same time, such as kidneys, skin, nerves and lungs |

| GPA | The vasculitis is accompanied by granulomatous inflammation: often affects the lung, sinuses, nose, eyes or ears |

| EGPA | Granulomatous polyangiitis and the patient also has asthma + eosinophilia |

Current clinico-pathological classification scheme modified from CHCC 2012 with categories of AAV [3]

| CHCC 2012 name . | CHCC 2012 definition . |

|---|---|

| RLV | Glomerulonephritis with no involvement of other organs |

| MPA | Injury to blood vessels in multiple tissues at the same time, such as kidneys, skin, nerves and lungs |

| GPA | The vasculitis is accompanied by granulomatous inflammation: often affects the lung, sinuses, nose, eyes or ears |

| EGPA | Granulomatous polyangiitis and the patient also has asthma + eosinophilia |

| CHCC 2012 name . | CHCC 2012 definition . |

|---|---|

| RLV | Glomerulonephritis with no involvement of other organs |

| MPA | Injury to blood vessels in multiple tissues at the same time, such as kidneys, skin, nerves and lungs |

| GPA | The vasculitis is accompanied by granulomatous inflammation: often affects the lung, sinuses, nose, eyes or ears |

| EGPA | Granulomatous polyangiitis and the patient also has asthma + eosinophilia |

MPO AND PR3 ANCA TYPE ARE MORE IMPORTANT THAN THE PATHOLOGY CLASSIFICATION

Whether GPA and MPA represent two distinct diseases, or the same entity in different moments in time, remains an open matter for debate [13]. Some patients can present initially with manifestations of MPA but subsequently develop new manifestations that are consistent with GPA. For example, applying the first CHCC of 1994, 78% of patients classified as MPA would be categorized as having GPA by the European Medicines Agency classification [4, 13, 14]. The treatment strategies for GPA and MPA are essentially identical, which has justified their inclusion together in clinical trials [15, 16]. Several classification systems based on clinico-pathological features have been proposed in order to describe homogeneous patient populations for their inclusion in clinical trials [3–6, 17–19], but by these schemas, the same patient could be classified differently depending on either the classification scheme used or the time course of the disease [13].

GPA and MPA are associated with both ANCA types [12]. In GPA, PR3 is present in ∼75% of cases, while MPO is present in less than one-quarter of patients (20%). In MPA, most patients have MPO-ANCAs (60%) but PR3-ANCAs can account for ∼30% of the cases [12, 20, 21]. As both ANCA types can be present in GPA and in MPA, the ANCA specificity does not always help in the differential diagnosis of GPA and MPA.

Patients with PR3-AAV do not share the same genetic background and pathophysiological mechanisms as patients with MPO-AAV [13, 22]. Distinct cytokine profiles were identified for PR3-AAV versus MPO-AAV and were more strongly associated with ANCA type than GPA versus MPA [23]. There are also several differences between the epidemiology, age at diagnosis, organ involvement, histopathology, prognosis, response to therapy and rate of relapses between MPO-ANCA and PR3-ANCA disease.

Differences in presentation between MPO-ANCA vasculitis and PR3-ANCA vasculitis

There are different demographic frequencies between ANCAs. For example, MPO-ANCA is more frequent in Southern Europe and Asia, while PR3-ANCA is more frequent in Northern Europe, USA and Australia [24–27]. Patients with MPO-ANCA vasculitis are typically older than PR3-ANCA patients in adults [12, 28], with scarce data in paediatric populations [29, 30].

Organ involvement in MPO-ANCA vasculitis is typically different from organ involvement in PR3-ANCA vasculitis [14, 31–36]. The ANCA type is the major determinant of clinical presentation [14] as shown in Figure 1. MPO-ANCAs are more likely to be kidney limited with >80% of patients having isolated crescentic glomerulonephritis [14]. In contrast, the vast majority (again >80%) of PR3-ANCA patients have disease activity in the lungs, upper respiratory tract, ears, nose and/or throat [14]. The frequency and the severity of extra-kidney organ involvement clearly differ between ANCAs. PR3-AAV shows a higher number of extra-kidney organ manifestations [34]. Upper airway disease with destructive lesions (nasal perforation and saddle nose) is typical in PR3 but rare in MPO. Respiratory involvement in PR3-ANCA is usually associated with cavitated nodules, while MPO-ANCA has lung fibrosis, honeycombing and interstitial pulmonary affectation [12, 31, 32]. Infiltrates and alveolar haemorrhage are equally associated with both ANCA types [14]. Comparing pathology features apart from common necrotizing vasculitis, granulomatous inflammation is typically associated with PR3-AAV, while non-granulomatous lesions and fibrosis are seen in MPO-AAV [28, 37, 38]. Kidney presentation is more acute with PR3, while MPO cases have more chronic lesions [12] on kidney biopsy. MPO-ANCA patients are more likely to have kidney pathology classified as mixed or sclerotic [37].

![Frequency distribution (%) of MPO-ANCA and PR3-ANCA positivity in patients with a particular organ system involved adapted from Lionaki et al. [14]. This cohort included patients with RLV, MPA and GPA, excluding patients with EGPA. Of the patients, 80% with kidney-limited glomerulonephritis have MPO-ANCA while only 20% are PR3-ANCA. MPO and PR3 have similar rates (∼50%) of lung involvement without nodules (infiltrates and alveolar haemorrhage). Additional skin lesions have similar rates for the two types of ANCA. Lung involvement with nodules is predominantly seen in PR3-ANCA. Nasal ulcers, crusting, destructive lesions, epistaxis and saddle nose are typical of PR3-ANCA and very rare in MPO-ANCA.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/ckj/14/5/10.1093_ckj_sfaa255/4/m_sfaa255f1.jpeg?Expires=1747915405&Signature=3bMNkRFSQClQCLlYeq4wCYidFXfYf3l5Gfr9uga8XUN3mluUf19raUGCkV4Bs1UQ~VbVtJRRInvGQhyPeJS1Es0GgBxtYyyBwGbSHx6wyd98JCBLKQA90QzK16ypBggI0oXAj9cSk3i7pvWwWSjV-nHjSKTEZJMc63luGPmKxtsXuL3giW0MCcn799ggwEgoVPssSmsU7qcl5YrcoxJioTVxQ35dnLZr0bjIYfD2Zz0eOFaZb6O1GP3SjA1MqoiVsWVqhoaLt5WmmlAo6D7ZrhC-HY~YuyH9-WHwEBnu9aEZ09DqYLLx4l7nDTqIqTiSn20LJd3De7~y83vZOJVIZA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Frequency distribution (%) of MPO-ANCA and PR3-ANCA positivity in patients with a particular organ system involved adapted from Lionaki et al. [14]. This cohort included patients with RLV, MPA and GPA, excluding patients with EGPA. Of the patients, 80% with kidney-limited glomerulonephritis have MPO-ANCA while only 20% are PR3-ANCA. MPO and PR3 have similar rates (∼50%) of lung involvement without nodules (infiltrates and alveolar haemorrhage). Additional skin lesions have similar rates for the two types of ANCA. Lung involvement with nodules is predominantly seen in PR3-ANCA. Nasal ulcers, crusting, destructive lesions, epistaxis and saddle nose are typical of PR3-ANCA and very rare in MPO-ANCA.

Differences in response rates for MPO-ANCA versus PR3-ANCA

According to a post hoc analysis of the Rituximab for ANCA-Associated Vasculitis (RAVE) trial, rituximab was significantly more effective than cyclophosphamide in the subgroup of patients with PR3-ANCA (65% versus 48% P-value 0.04) [36]. Rituximab might be superior to cyclophosphamide for remission induction in PR3-AAV, and PR3 titre might guide therapy after rituximab, while MPO-AAV has a similar response to rituximab and cyclophosphamide [36, 39]. In RAVE, more patients with PR3-ANCA became seronegative with rituximab (50%) compared with cyclophosphamide (17%) (P = 0.004 for comparison), while similar rates of negative MPO-ANCA patients were reported respectively comparing rituximab and cyclophosphamide (40% versus 41%) [35].

In numerous studies, treatment resistance has been defined in AAV as persistence or new appearance of extra-kidney manifestations and/or progressive decline in kidney function with active urine sediment in spite of immunosuppressive therapy [40–42]. MPO-ANCA patients have a higher risk of treatment resistance [40]. A serological classification based on the comparison of the two ANCA types was able to show differences in response rates in retrospective analyses: 27% of MPO-ANCA patients had treatment resistance versus 17% of PR3-ANCA patients (P < 0.02 for comparison) [11, 14]. The ANCA type appears to better predict response rates than the traditional disease classification based on histopathology: MPO-ANCA versus PR3-ANCA (serological classification) but no clinical diagnosis of MPA versus GPA was associated with treatment resistance in some [40], but not all [43] retrospective series. In the Lionaki et al. study [14], which excluded EGPA and followed the classification based on CHCC 2012, 30% of RLV were treatment-resistant compared with 22% of MPA and 17% of GPA, without significant differences (P = 0.07). The European Medicines Agency classification [4], using this same cohort, was also not able to predict differences in response [11, 14].

MPO release after neutrophil and monocyte activation can generate reactive oxygen species, leading to tissue damage. The use of a selective MPO inhibitor significantly attenuates these pathways and reduces disease severity in a preclinical crescentic glomerulonephritis model [44]. Therefore, MPO contributes to ANCA-mediated endothelial damage and is critically implicated in crescentic glomerulonephritis.

The rates of end-stage kidney disease (chronic dialysis or kidney transplantation) were higher in MPO-ANCA patients (37%) than in PR3-ANCA patients (26%) (P < 0.01) [14]. This feature was also predicted with CHCC 2012 classification however (41% RLV, 30% MPA and 21% GPA, P < 0.001), and by comparing GPA and MPA with European Medicines Agency classification (P < 0.02).

Finally, all-cause mortality was predicted by classifications based on ANCA types (31% MPO-ANCA versus 23% PR3-ANCA, P < 0.03) and on CHCC 2012 (33% RLV, 30% MPA and 17% GPA, P < 0.01), but not by European Medicines Agency classification (P = 0.25) [11, 14]. In several studies, mortality was higher in MPO-ANCA but this difference was usually not statistically significant after adjustment for age at diagnosis, given that MPO-ANCA patients are, on average, older than PR3-ANCA patients [14, 26, 45, 46].

The ANCA type subdivision provides the best predictive model compared with the classification based on the CHCC 2012 definitions or the European Medicines Agency classification [11]. For this reason, the CHCC 2012 calls for adding a prefix with the ANCA type to the clinico-pathological phenotype [3, 11]. A large study of 673 patients with GPA or MPA found that the addition of ANCA differentiation to a single clinical clustering improved the classification of patients into distinct categories with different outcomes [47]. ANCA specificity reflects the phenotype spectrum of AAV better and has prognostic significance. However, worse outcomes comparing ANCA serology are not uniformly accepted [48, 49].

Difference in relapse rates for MPO-ANCA versus PR3-ANCA

ANCA subtype has better predictive value with respect to long-term outcome and relapse propensity than do either terms GPA or EGPA [40]. Several studies have demonstrated that relapses are more frequent in patients with PR3-AAV compared with MPO-AAV. In multivariate analysis of these studies, positive PR3-ANCA was the most important factor associated with relapse risk [14, 50–53]. Reappearance of ANCAs (both types) after a negative result is also associated with relapses [54–56]. The persistence of MPO-ANCAs after induction therapy seems to have no risk of relapse [53]. However, contradictory results of relapse risk after induction therapy have been reported in cases of persistence of PR3-ANCA. According to a retrospective study, the relapse risk was high if PR3-ANCA levels persisted after induction therapy with cyclophosphamide [53], although these results were not confirmed in a prospective study [57]. In the important Lionaki et al. [14] study, 51% of patients with PR3-ANCA had relapses defined as reactivation of vasculitis in any organ after initial response to treatment, compared with 29% of patients with MPO-ANCA (P < 0.001).

In the CYCLOPS trial (comparing induction treatment of oral continuous versus pulsed cyclophosphamide) and the CYCAZAREM trial (comparing early and late switch from oral cyclophosphamide to azathioprine), risk of relapse was significantly higher in the PR3-AAV compared with MPO-AAV [58, 59]. ANCA negativity but not ANCA specificity was associated with lower relapse rate in REMAIN (prolonged REmission-MAINtenance therapy in systemic vasculitis) trial that compared prolonged maintenance treatment with azathioprine/prednisone (24 months versus 48 months) [60]; this was re-evaluated in a post hoc analysis of pooled data of six randomized controlled trials, concluding that relapse rates were associated to PR3-ANCA rather than to the length of maintenance treatment [61]. In the MYCYC (MYcophenolate Versus CYClophosphamide in ANCA vasculitis) trial that compared mycophenolate with cyclophosphamide, PR3-ANCA patients also presented increased relapse risk compared with MPO-ANCA [62].

Genome-wide association study data confirm that MPO versus PR3 is the best phenotype for vasculitis

Genome-wide association study (GWAS) demonstrated a stronger genetic association between ANCA antigen specificity rather than with a specific clinical syndrome [22, 63]. In this landmark study, MPO-AAV was associated with HLA-DQ, while PR3-AAV was associated with HLA-DP, SERPINA 1 and PRTN3 genes [22]. HLA-DPB1 haplotype could also be an important determinant for relapse risk [64]. The overlap of ANCA types within the clinical syndromes strengthens the idea of dividing MPO-ANCA and PR3-ANCA vasculitis as distinct autoimmune syndromes [12]. MPO-positive EGPA is an eosinophilic autoimmune disease sharing certain clinical features and an HLA-DQ association with MPO + AAV, while ANCA-negative EGPA may instead have a mucosal/barrier dysfunction origin [65].

The GWAS study gave an independent, non-clinically based line of support that the most appropriate classification scheme for AAV is based on ANCA subtype.

PROPOSAL FOR CLASSIFICATION ACCORDING TO (i) ANCA TYPE AND (ii) ORGAN INVOLVEMENT

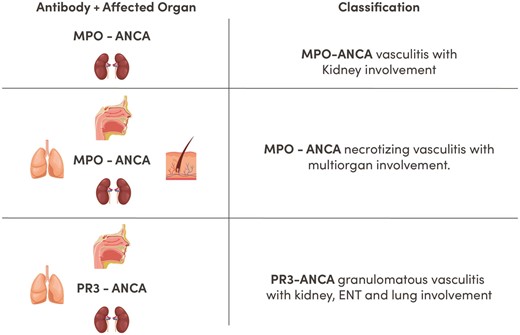

The ANCA type is a major determinant of presentation in AAV, providing important clinical information that includes organ predilection. We therefore propose a clinical classification (Table 2;Figure 2) dividing ANCA-associated disease into antibody type and organ involvement. For example:

Proposed classification of AAV kidney disease. Proposed classification according to ANCA type and organ involvement. Providing direct information about prognosis, severity, risks of relapse, type of treatment required and likelihood of response. ENT, ear, nose, throat.

| Name . | Definition . |

|---|---|

| MPO-ANCA necrotizing vasculitis with kidney involvement | Glomerulonephritis with no involvement of other organs with MPO-ANCA |

| MPO-ANCA necrotizing vasculitis with multiorgan involvement (skin, lungs) | Injury to blood vessels in multiple tissues at the same time and MPO-ANCA can depend on the case: kidneys, skin, nerves and lungs |

| PR3-ANCA granulomatous vasculitis with lung and kidney involvement | Vasculitis with PR3-ANCA accompanied by granulomatous inflammation can depend on the case: lung, sinuses, nose, eyes or ears |

| Name . | Definition . |

|---|---|

| MPO-ANCA necrotizing vasculitis with kidney involvement | Glomerulonephritis with no involvement of other organs with MPO-ANCA |

| MPO-ANCA necrotizing vasculitis with multiorgan involvement (skin, lungs) | Injury to blood vessels in multiple tissues at the same time and MPO-ANCA can depend on the case: kidneys, skin, nerves and lungs |

| PR3-ANCA granulomatous vasculitis with lung and kidney involvement | Vasculitis with PR3-ANCA accompanied by granulomatous inflammation can depend on the case: lung, sinuses, nose, eyes or ears |

Patients with AAV kidney disease can have a variety of symptoms not mentioned, as, for example, neurological, ophthalmological, gastrointestinal, etc., as delineated in a thorough assessment using the Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score [66].

| Name . | Definition . |

|---|---|

| MPO-ANCA necrotizing vasculitis with kidney involvement | Glomerulonephritis with no involvement of other organs with MPO-ANCA |

| MPO-ANCA necrotizing vasculitis with multiorgan involvement (skin, lungs) | Injury to blood vessels in multiple tissues at the same time and MPO-ANCA can depend on the case: kidneys, skin, nerves and lungs |

| PR3-ANCA granulomatous vasculitis with lung and kidney involvement | Vasculitis with PR3-ANCA accompanied by granulomatous inflammation can depend on the case: lung, sinuses, nose, eyes or ears |

| Name . | Definition . |

|---|---|

| MPO-ANCA necrotizing vasculitis with kidney involvement | Glomerulonephritis with no involvement of other organs with MPO-ANCA |

| MPO-ANCA necrotizing vasculitis with multiorgan involvement (skin, lungs) | Injury to blood vessels in multiple tissues at the same time and MPO-ANCA can depend on the case: kidneys, skin, nerves and lungs |

| PR3-ANCA granulomatous vasculitis with lung and kidney involvement | Vasculitis with PR3-ANCA accompanied by granulomatous inflammation can depend on the case: lung, sinuses, nose, eyes or ears |

Patients with AAV kidney disease can have a variety of symptoms not mentioned, as, for example, neurological, ophthalmological, gastrointestinal, etc., as delineated in a thorough assessment using the Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score [66].

MPO-ANCA vasculitis with kidney involvement;

MPO-ANCA necrotizing vasculitis with lung, skin and kidney;

PR3-ANCA granulomatous vasculitis with lung and kidney involvement.

Seronegative ANCA disease can equally be classified as necrotizing or granulomatous, adding the organ involved and specifying the ANCA negativity (e.g. ANCA-negative vasculitis with kidney and joint involvement). ANCA-negative patients seem to have a different pathogenic process with more prominent complement activation [67] and might represent an independent disease entity from ANCA-positive vasculitis [68].

An additional prefix (focal, crescentic, mixed and sclerotic) can be added using the Berden et al. classification [69], providing information on the histological activity in patients with performed kidney biopsies: focal, ≥50% normal glomeruli; crescentic, ≥50% glomeruli with cellular crescents; mixed, <50% normal, <50% crescentic, <50% globally sclerotic glomeruli; and sclerotic, ≥50% globally sclerotic glomeruli. Focal class is associated with favourable kidney outcome, whereas sclerotic carries a poor outcome [69]. Crescentic/mixed class could have an intermediate outcome between focal and sclerotic [70].

For example:

Crescentic MPO-ANCA vasculitis with kidney involvement;

Mixed MPO-ANCA necrotizing vasculitis with multiorgan involvement (kidney, skin, lungs);

Focal PR3-ANCA granulomatous vasculitis with lung, nose and kidney involvement;

Mixed ANCA-negative granulomatous vasculitis with lung and kidney involvement.

In sum, the current classifications used for AAVs are descriptive and histologically based. Classifying patients on the basis of MPO-ANCA versus PR3-ANCA correlates better with disease characteristics [71]. Other classifications have been proposed on the basis of ANCA status such as Mahr et al. [72] subclassifying AAV into (i) non-severe AAV (usually PR3/sometimes negative/granulomatous with no kidney involvement/high relapse and low life-organ threatening), (ii) severe PR3 AAV (mixed granulomatous/kidney involvement and intermediate risk life-organ threatening) and (iii) severe MPO-AAV (kidney involvement/vasculitic features/high-risk life-organ threatening and low relapse). This interesting view was discussed by Lamprecht et al. [73], who commented that renaming a limited GPA as non-severe AAV with the destructive nature of granulomatous lesions will appear an underestimation in relation to the patient disease burden. This will also substitute the distinction between localized, early systemic and generalized forms of AAV that informed about severity and localization of lesions [73]. Furthermore, it does not inform about the organs involved, which we believe is important to individualize cases and does not reflect the dynamic nature of this disease, as non-severe forms can change. Pulmonary haemorrhage, for example, which affects 10% of AAV is associated with an increased risk of death [74, 75]. The presence of pulmonary haemorrhage can change the clinical approach, the vital prognosis in the short-term and the multidisciplinary approach, sometimes requiring intensive care unit management. In limited situations induction therapy could require plasma exchange in ANCA-induced pulmonary haemorrhage, especially with concomitant anti-glomerular basement membrane disease [76]. Therefore, we believe that in a classification of AAV the information regarding the organ involved is practical. The need to treat extra-kidney involvement in vasculitis may influence treatment choices for kidney vasculitis and maintenance therapy in AAV [75, 77]. For the difficult task of creating a new classification in AAV, consensus between different societies is needed.

The classification proposed in this article provides clinicians with important information that is easily communicable to individualize medical attention in AAV patients. For example, the type of ANCA can give information on risk of relapse, presentation and response rates. The organ involved can inform about the aggressiveness and destructive lesions of organs involved. And finally, the histological Berden et al. classification [69] highlights the importance of kidney biopsy in AAV in terms of providing information on kidney outcomes. We present two illustrative cases to demonstrate this proposed classification:

Case 1: A 52-year-old woman appears in the emergency department with ‘flu-like’ symptoms for 3 weeks, haemoptysis, 2-kg weight loss and nasal crusting. Physical examination reveals purpura in lower extremities and elevated blood pressure (160/95 mmHg). Laboratory test shows an acute kidney injury with a serum creatinine of 3.1 mg/dL and active sediment with proteinuria and haematuria on urinalysis. PR3-ANCA is positive with a titre of 45 U/mL, with the remainder of immunological studies negative (including anti-glomerular basement membrane). Kidney biopsy cannot be performed despite recommendations as the patient does not consent to receive the procedure.

Computed tomography (CT) of the chest reveals cavitated nodules in lung.

Clinical diagnosis: PR3-ANCA vasculitis with lung, skin, nose and kidney involvement.

Case 2: A 70-year-old male presents in the emergency department brought by his son who is concerned that his father is declining, with increased fatigue and poor appetite. Physical examination is normal and blood pressure is 140/95 mmHg. Laboratory test shows a serum creatinine of 8.6 mg/dL and active sediment with proteinuria and haematuria on urinalysis (urine albumin to creatinine ratio 750). MPO-ANCA is positive with a titre of 72 U/mL; other immunological studies are negative. CT scan of the brain is unremarkable. A kidney biopsy is performed with the result of necrotizing crescentic glomerulonephritis on light microscopy and pauci-immune staining pattern on immunofluorescence microscopy with ≥50% globally sclerotic glomeruli.

Clinical diagnosis: Sclerotic MPO-ANCA vasculitis with kidney involvement.

ANCA specificity, kidney function and the type of extra-kidney involvement should be considered to assess the risk of relapses and select the induction and maintenance treatment [77]. In new-onset severe PR3- and MPO-AAV, corticosteroids in combination with rituximab or cyclophosphamide can be used as induction therapy (limited data for rituximab in severe kidney involvement serum creatinine >4 mg/dL are available) [75, 78]. In PR3-AAV with preserved kidney function with higher risk of relapses and extra-kidney involvement, maintenance therapy with rituximab may be the best option [77]. In MPO-AAV presenting with kidney failure without extra-kidney disease, the risk of relapses progressively declines with increasing serum creatinine [77, 79], so the risk of infectious complications from immunosuppression might outweigh the benefits of relapse prevention and influence the length of maintenance therapy [75, 77]. Maintenance treatment could have more importance in PR3-AAV and in multiorgan involvement compared with MPO-AAV with kidney involvement and without extra-kidney affectation [77]. The severity of organ and life-threatening disease determines the choice of treatment according to the consensus reached so far by KDIGO 2020 Guidelines Draft, while ANCA specificity as PR3, relapsing disease, frail older adults, steroid-sparing or fertility issues and others are factors for consideration [75].

CONCLUSIONS

The classification of AAV has changed over the years. We have left behind the honorific eponyms and moved to a descriptive-based classification scheme (CHCC 2012). Nevertheless, in our opinion, a classification system should also help as a practical tool for disease recognition, treatment decisions and prognostic prediction in clinical practice, and not be limited to providing definitions or descriptions of disease. There is probably no perfect classification for AAV kidney disease, as sometimes patients do not perfectly fit. An initial isolated organ involvement can evolve to new organs being affected. This classification gives the opportunity to add new organ affections easily if they appear, recognizing the dynamic nature of this disease. The proposed clinical classification may contribute to individualize cases and give information about the localization of lesions aside from the kidneys, and may provide information on the risk of relapse, likelihood of response, prognosis and factors for consideration in management, although therapy decisions may be determined by the severity of the disease. The definitions of GPA versus MPA and GPA versus EPGA do not predict long-term outcomes or propensity for relapse as strongly as serological tests for MPO-ANCA and PR3-ANCA. ANCA serological subclassification has been supported by genetic and cytokine profile differences. This simple nomenclature using ANCA type and organ involvement with an additional histological prefix (if kidney biopsy is available) can help clinicians with the difficult task of treating ANCA-associated kidney disease patients.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

REFERENCES

KDIGO Clinical Practice guideline on Glomerular Diseases. Public review draft.

Comments