-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Adrian Smith, Economic (in)security and global value chains: the dynamics of industrial and trade integration in the Euro-Mediterranean macro-region, Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, Volume 8, Issue 3, November 2015, Pages 439–458, https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsv010

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The European Union (EU) has been engaged in a project of macro-regional integration with selected North African countries, increasing inter-dependent economic relations. Trade has been liberalised, global value chains extended and EU firms have established industrial production activity. This paper examines the consequences for economic insecurity in the region, in the context of trade integration, the Tunisian ‘Arab Spring’ and the enduring economic crisis in the EU. It questions whether economic integration is leading to industrial upgrading and improvement in working conditions and argues that, while economic growth was fostered on the basis of this model, it has also created conditions for economic insecurity and uneven development.

Introduction

Global value chains (GVCs) research has focused attention on the degree to which integration into the global economy leads to positive development outcomes for firms, regional economies and workers (Bair and Gereffi, 2002, 2003; Barrientos et al., 2011; Gereffi, 1994; Gibbon and Ponte, 2005, Pickles et al., 2006; Smith et al., 2002; Yeung and Coe, 2015). A central component of this framework is the relationship between international economic integration and industrial—and more recently, social—upgrading (for example, Bair and Gereffi, 2002, 2003; Barrientos et al., 2011; Milberg and Winkler, 2013). Reflecting the recognition that the world economy is one of increasingly inter-dependent economic networks (Dunford and Yeung, 2011; Dunford et al., 2012; Smith, 2013), GVC frameworks have also become increasingly influential in informing international development policy and a range of global development institutions. With its origins in the adoption by the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) in the early 2000s, and largely because of its emphasis on determinants of and strategies for industrial upgrading, the GVC framework is now a central component of development strategy and policy for many of the leading international development agencies (see Neilson, 2014; Werner et al., 2014; Yeung and Coe, 2015). This paper provides new conceptual perspectives on the intersection of trade, economic integration and industrial and employment upgrading. It does so by reframing the focus on upgrading towards the relationship between economic integration and economic (in)security. The paper argues that linear conceptions of upgrading inadequately capture the diversity of firm dynamics, and can tend towards modernisationist conceptions of development (see also Bair and Werner, 2011; Pickles and Zhu, 2015; Pickles et al., 2006). The paper suggests that there is a profitable engagement to be had between debates over industrial and social upgrading, and economic (in)security generated by the integration of industries into the global economy.

The paper focuses on the macro-regional preferential trade arrangements between the European Union (EU) and Tunisia, which were established in 1995 via a bilateral free trade agreement (FTA) as part of the so-called ‘Barcelona process’ of Euro-Mediterranean integration (Bialasiewicz, 2011; Bialasiewicz et al., 2009; Casas-Cortes et al., 2013; Jones, 2006). This focus is taken for two primary reasons. First, inscribed into the FTA was a fundamental relationship between trade and development; with the view taken that increasing trade liberalisation would enhance the economic security of Tunisia to prevent geo-political instability, illegal migration and the rise of Islamism (Hunt, 2011; Smith, 2015). It was also concerned with providing opportunities for new investment and capital accumulation opportunities for EU businesses in locations proximate to the Single Market (Smith, 2014). Second, the 2011 ‘Arab Spring’ revolution made clear the limits of this model of economic integration. This model was characterised by a particular form of ‘exportist’ development strategy underpinned by domestic dictatorship and Tunisian presidential and familial control over the commanding heights of the economy (Bellin, 1994; Erdle, 2010; Rijkers et al., 2014; Smith, 2014; see also Jessop and Sum, 2006). Investigation of the trade and macro-regional integration of GVCs in the Tunisian context thus raises important conceptual and empirical issues concerning the relationship between GVCs and economic (in)security.

The concern with economic (in)security in GVCs refocuses the debate on upgrading in relation to a political economy of (in)security by recognising the range of possible firm trajectories and their variant developmental outcomes for workers and regional economies. Rather than focusing solely on the ‘inclusionary bias’ (Bair and Werner, 2011, 989) of upgrading and its positive developmental outcomes, the paper suggests that deepening economic integration in Tunisia, and responses to the crises surrounding the ‘Arab Spring’ and economic insecurity in core EU markets, are leading to a differentiation in the security of firms and workers integrated into GVCs. The paper examines this conceptualisation of economic insecurity in two ways. First, the paper examines how a model of development centred on integration into GVCs had consequences for the economic insecurity and uneven development of the Tunisian economy. The paper focuses on the role of clothing GVCs as a fundamental element of this ‘exportist’ model, which resulted in very significant levels of integration into the EU economy alongside internal regional uneven development and political-economic insecurity ultimately, at least in part, leading to the ‘Arab Spring’. Second, at the scale of firms operating in the clothing sector the paper examines the extent to which industrial and worker upgrading are affecting the position of firms in the value chain and improving (or not) working conditions and the economic security of workers after the ‘Arab Spring’. I argue that the way in which the industry has transformed in the context of the ‘perfect storm’ of these two main forces—the political-economic uncertainty arising from the ‘Arab Spring’ and the EU economic crisis—has been shaped by the structural position of firms in value chains and the extent to which local demands from workers have been translated into calls for increasing wages and improvements in working conditions. These conditions are differentiating the outcomes for firms, with limited evidence of upgrading for some, alongside greater insecurity for others. In other words, the paper focuses on both the longer term dimensions of economic (in)security derived from FTAs and macro-regional integration projects, as well as the conjunctural dimensions of restructuring arising from the ‘Arab Spring’ and the economic crisis.1 As such it contributes to recent work concerning the uneven developmental consequences of integration into GVCs (Bair, 2005; Bair and Werner, 2011; Havice and Campling, 2013; Pickles and Smith, 2015; Pickles et al., 2006), and that recognising the ways in which value chain integration has created conditions in which economic crisis and market downturns become translated across networks of globalised production (Cattaneo et al., 2010; Smith and Swain, 2010). The paper is based on research involving 61 key informant and firm interviews in Tunisia, Brussels and London, including 39 firms in the clothing sector in two major producing regions (Tunis and Monastir) conducted between 2012 and 2014 (an 8% sample of the estimated population of firms in the sector in the two regions). The sample involved a range of firms, including some of the largest, most important and most powerful players in the two regions.

The next section of the paper elaborates the relationship between upgrading, downgrading and economic (in)security in GVCs. This is followed by a discussion of the process of Euro-Mediterranean economic integration, the FTAs between the EU and Tunisia and the nature of the development model which resulted, charting their implications for economic (in)security and uneven development. The paper then turns to examine the differentiated dimensions of upgrading and downgrading in firms and the economic security consequences for both firms and workers, particularly following the ‘Arab Spring’.

Economic (in)security in GVCs

How might we theorise the relationship between international economic integration through GVCs and economic (in)security? This section of the paper extends the debate on upgrading in GVCs towards a consideration of economic (in)security in order to provide a framework for understanding the developmental consequences of integration into EU value chains.

Bair and Gereffi (2003, 147) defined the upgrading of firm activity in the global clothing industry in terms of “a series of role shifts involved in moving from export-oriented assembly to more integrated forms of manufacturing and marketing” (original equipment manufacturing (OEM or full-package production) and original brand manufacturing (OBM) export). This identification of functional upgrading has been a key element of research on GVCs. Humphrey and Schmitz (2002) identified four types of upgrading in GVCs (see also Gibbon and Ponte, 2005, 89): process upgrading (the reorganisation of the production system and/or the introduction of new technologies to achieve greater efficiency in the transformation of inputs into outputs); product upgrading (the production of more sophisticated products which enables firms to capture and appropriate greater unit value); functional upgrading (the acquisition and adoption of new elements in the production process, again allowing firms to capture greater proportions of value by increasing the skill content of its activities) and inter-sectoral or chain upgrading (a firm taking its technological, skill and product competencies and applying them in new product areas and new sectors).

In the clothing sector, these forms of industrial upgrading can be mapped onto specific processes and stages in the clothing value chain with upgrading involving a functional shift from export-oriented sewing and assembly work (cut-make (CM) and cut-make-trim (CMT)) to OEM or full-package production (Bair and Gereffi, 2003, see also Bair and Gereffi, 2002). This focus on upgrading tends to provide little space for a consideration of the diversity of trajectories which firms may adopt in the pursuit of attempting to enhance competitive positions in GVCs (Pickles and Smith, 2015; Pickles and Zhu, 2015; Pickles et al., 2006; Tokatli, 2013). Each of these typologies of upgrading concerns strategies to capture additional value from manufacturing operations at a particular segment in the value chain. However, upgrading research, particularly where it examines national trajectories and trade data, tends to focus on linear trajectories of industrial improvement in GVCs, without considering the full range of scenarios experienced in particular regional economies, how these might be differentiated across firms operating within one sector with different consequences for the economic security of firms and workers, and how value chain integration potentially exposes firms to external shocks by creating deep levels of inter-dependence (Cattaneo et al., 2010; Smith and Swain, 2010). Recognition that firms integrated into GVCs can experience divergent trajectories of upgrading, downgrading, inclusion and exclusion, often dependent on the strategies of lead firms in relation to the capabilities of local producers (Bair and Werner, 2011; Gibbon and Ponte, 2005; Pickles et al., 2006), means that it is helpful to re-frame this diversity of trajectories in the wider context of their impact on the economic (in)security of firms, workers and regional economies (Coe and Jordhus-Lier, 2011; Coe et al., 2008; Cumbers et al., 2008; Selwyn, 2012; Smith et al., 2002). For Werner (2012, 407), “the upgrading analytic [in GVCs] centres industrial change on the relations of power and dynamics of competition among firms, rendering the social relations that mediate the production of exploitable workers and the conditions of their exploitation marginal to the analysis” (Werner, 2012, 407; see also Smith et al., 2002, 47). Azmeh (2014), for example, has highlighted the importance of understanding production and labour control regimes in providing sufficient and appropriate labour for the needs of international capital in global production networks. Azmeh emphasises how this provision is contingent upon different political-economic circumstances and struggles in contrasting contexts.

Consequently, economic security is considered in this paper in relation to two dimensions. The first dimension involves the economic security of firms integrated into clothing GVCs, relating to the extent to which firms are able to reposition in GVCs and to upgrade to provide a degree of stability and security in globalised industries. The paper examines the degree to which firms have been able to adopt strategies leading to functional, product and process upgrading and the different consequences of these strategies for the growth and security of these firms. However, as Bair (2005, 154) has argued “because the upgrading concept is focused narrowly on the issue of firm-level competitiveness within the context of a particular industry, it sheds a very partial light on the critical question of winners and losers in today’s global economy” (Bair and Werner, 2011; Smith et al., 2002; Werner, 2012). As such, it says little about the wider consequences of integration into GVCs for the economic development and (in)security of firms, workers and territories. Consequently, the second dimension considers how the economic security of firms affects the lives and livelihood capabilities of workers in global industries and regional economies (unevenly) integrated into GVCs. This connects in part to the wider focus on social upgrading (Barrientos et al., 2011; see Selwyn (2013) for a critique), but extends it to consider the extent to which involvement in GVCs and the differentiated upgrading of firms creates conditions in which employment security is enhanced.2

Milberg and Winkler (2013) have usefully examined the relationship between economic security and outsourcing in core economies. They argue that economic insecurity for workers has increased in core markets due to the outsourcing of economic activity and the globalisation of value chains. They highlight the differentiated nature of social upgrading across the Global South at both national and sectoral levels; economic security is seen as one outcome of a range of changes in living standards, wages, working conditions and economic rights. In what follows I extend this conceptualisation to examine the relationship between integration into GVCs, bilateral trade agreements, and the changing forms of security and insecurity which global economic interdependencies give rise to. Understanding (in)security in GVCs requires a focus on the employment dynamics arising from global economic integration and on the consequences of a precarious reliance on export-oriented GVCs and accumulation regimes. It also requires an understanding of the inter-dependence between firm strategy and employment outcomes. I argue that it is through the combination of different experiences of upgrading and downgrading of firms within the value chain (industrial upgrading/downgrading) with different consequences for employment and working conditions (social upgrading/downgrading) that we can begin to understand the relationship between economic (in)security, the developmental consequences of integration into GVCs, and the increasing interdependency of the global economy.

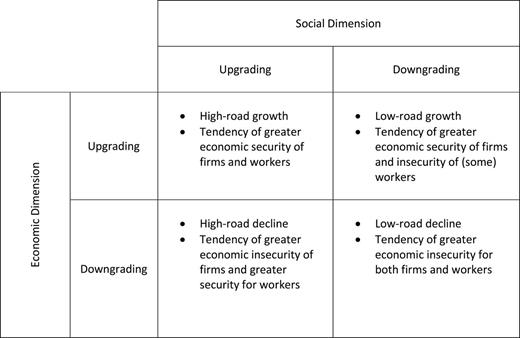

As Plank et al. (2012, 3) have argued, the expansion of employment associated with the integration of firms into GVCs often masks increasing flexibility, uncertainty and precariousness. Consideration of this issue is of fundamental importance in relation to the wider Tunisian employment crisis which generated social pressure leading to the ‘Arab Spring’. Attention needs to be given to the extent to which export-oriented integration into EU production networks created the basis for sustainable and secure employment. Consequently, there is an important relationship between economic and social upgrading and downgrading and economic (in)security (Figure 1). Firm-level growth may (‘high-road growth’) or may not (‘low-road growth’) be associated with employment gains and improvements in the position of workers: social upgrading in one firm may occur alongside increasing employment insecurity in others or among workers in the same firm. For different types of workers, different experiences of employment may be felt within a single firm between core, permanent workers and those with temporary contracts (Plank et al., 2012). At the same time, firm-level activity may not only exhibit tendencies towards upgrading, but towards decline (‘high/low-road decline’ in Figure 1). Firm downgrading may result from a number of distinct causes including, but not limited to, pressure from lead firms to reduce contract prices and the share of value attributed to assembly firms in a cost-sensitive industry such as clothing (Hale and Wills, 2005), or due to re-positioning within a value chain to ensure access to steady contracts but involving fewer assembly firm capabilities (see also Pickles et al., 2006). The institutional environment of firm-contracting and value chain management may thus mean that global buyers put pressure on supplier firms to such an extent that they are not able to effectively upgrade. This can occur because it is advantageous for lead firms to keep supplier firms in an insecure, dependent or arms-length relationship, able to respond flexibly to purchasing requirements, invariably with deleterious consequences for workers even if jobs are retained in the short term.

The relationship between economic/social upgrading and economic (in)security.

Source: Elaborated and extended from Milberg and Winkler (2013)

Macro-regional economic and trade integration, the ‘Arab Spring’ and economic (in)security

Since the late 1970s the Tunisian economy has been steadily integrated into the macro-economic space of the former European Economic Community (EEC) (now the Single Market of the EU). This integration has to a large extent been driven by the extension of manufacturing value chains, organised around a state-led development strategy involving significant degrees of paternalistic control over economic development (as well as over the wider political economy and social life of Tunisia) by the former President Ben Ali and extended family members and their clientilistic networks (Bellin, 1994; Erdle, 2010; Smith, 2014). This section considers this model of economic development and integration with the EU economy, the role of the clothing industry within it and its consequences for economic insecurity, leading to the ‘Arab Spring’ revolution in 2011. The argument is that economic insecurity and uneven economic integration into GVCs became major, albeit not the only, dynamics behind the geographical and regional underpinnings of the 2011 ‘Arab Spring’ revolution.

The formative events in the integration of the Tunisian economy into the EU’s economic sphere of influence via GVCs were two-fold: first, the customs and co-operation agreement between Tunisia and the EEC from 1976 allowed for the duty free entry without quantitative limit of Tunisian industrial goods into the EU3 and, second, the bringing into force of the EU-Tunisia FTA in 1998 as part of an Association Agreement, which was one element of the wider ‘Barcelona Process’ of EU-North African co-operation (Boughzala, 2012; Casas-Cortes et al., 2013).4 The 1976 agreement placed voluntary restrictions on the export of certain Tunisian textile and clothing products to the EEC, due to sensitivities over the competitive position of the industry within Europe (Commission of the European Communities, 1982). However, even with these limits in place, clothing imports from Tunisia accounted for 24% of total imports and 53% of manufactured goods imports by 1980 (Commission of the European Communities, 1982). The 1998 FTA provided for duty free entry of a significant proportion of industrial products from Tunisia into the EU, including textiles and clothing. It also enabled the harmonisation of the regulatory framework for trade, removed quantitative restrictions on imports and led to the progressive increase in economic linkages. As a consequence, by the late 1990s EU countries accounted for 70% of Tunisian imports, 80% of exports and 90% of foreign direct investment, with France, Italy and Germany representing three-quarters of non-resident firms (Erdle, 2010, 365). The textile and clothing sector became a central component of this ‘exportist’ model of economic integration through value chains co-ordinated by EU lead firms contracting with Tunisian-based firms and West European clothing firms engaged in direct investment in the country. At its height between 2001 and 2003, textile and clothing firms employed 45% of manufacturing workers in Tunisia, accounted for almost one-third of manufacturing exports to the EU in 2011,5 but paid the lowest salaries in the Tunisian manufacturing sector (Table 1). In this sense, the Tunisian experience has its parallels with that in East-Central Europe which became locked into clothing export production for EU markets as a result of outward-processing trade arrangements and later deeper preferential regional trade agreements, as part of the EU ‘golden bands’ approach to macro-regional economic integration (Begg et al., 2003; Pickles and Smith, 2015; Plank et al., 2012). Estimates suggest that approximately 80% of the total value of Tunisian clothing production is for export to EU markets,6 although recently the share of the EU market attributed to Tunisian exports has declined in the face of increasing competitive pressures arising from the phasing out of the Multi-Fibre Arrangement (Pickles and Smith, 2011).

Average salary and other wage benefits in the main manufacturing sectors, Tunisia, 2011 (Tunisian dinar).

| . | Textiles and clothing . | Other manufacturing . | Chemical . | Construction materials . | Mechanical and electrical engineering . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Net base salary | 353.6 | 398.0 | 438.9 | 430.5 | 503.7 | 482.5 |

| Regular premiums | 42.2 | 35.5 | 154.1 | 70.6 | 78.7 | 60.0 |

| In-kind benefits | 9.1 | 0.9 | 6.2 | 6.4 | 0.0 | 6.6 |

| Overtime | 4.0 | 0.0 | 12.4 | 8.9 | 6.0 | 8.3 |

| Total wages | 408.8 | 434.3 | 611.7 | 516.4 | 588.4 | 557.3 |

| Men | 461 | 467 | 628 | 525 | 800 | 615 |

| Women | 392 | 368 | 537 | 377 | 385 | 459 |

| . | Textiles and clothing . | Other manufacturing . | Chemical . | Construction materials . | Mechanical and electrical engineering . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Net base salary | 353.6 | 398.0 | 438.9 | 430.5 | 503.7 | 482.5 |

| Regular premiums | 42.2 | 35.5 | 154.1 | 70.6 | 78.7 | 60.0 |

| In-kind benefits | 9.1 | 0.9 | 6.2 | 6.4 | 0.0 | 6.6 |

| Overtime | 4.0 | 0.0 | 12.4 | 8.9 | 6.0 | 8.3 |

| Total wages | 408.8 | 434.3 | 611.7 | 516.4 | 588.4 | 557.3 |

| Men | 461 | 467 | 628 | 525 | 800 | 615 |

| Women | 392 | 368 | 537 | 377 | 385 | 459 |

Source: Elaborated from International Labour Organization (ILO) (2012).

Average salary and other wage benefits in the main manufacturing sectors, Tunisia, 2011 (Tunisian dinar).

| . | Textiles and clothing . | Other manufacturing . | Chemical . | Construction materials . | Mechanical and electrical engineering . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Net base salary | 353.6 | 398.0 | 438.9 | 430.5 | 503.7 | 482.5 |

| Regular premiums | 42.2 | 35.5 | 154.1 | 70.6 | 78.7 | 60.0 |

| In-kind benefits | 9.1 | 0.9 | 6.2 | 6.4 | 0.0 | 6.6 |

| Overtime | 4.0 | 0.0 | 12.4 | 8.9 | 6.0 | 8.3 |

| Total wages | 408.8 | 434.3 | 611.7 | 516.4 | 588.4 | 557.3 |

| Men | 461 | 467 | 628 | 525 | 800 | 615 |

| Women | 392 | 368 | 537 | 377 | 385 | 459 |

| . | Textiles and clothing . | Other manufacturing . | Chemical . | Construction materials . | Mechanical and electrical engineering . | Total . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Net base salary | 353.6 | 398.0 | 438.9 | 430.5 | 503.7 | 482.5 |

| Regular premiums | 42.2 | 35.5 | 154.1 | 70.6 | 78.7 | 60.0 |

| In-kind benefits | 9.1 | 0.9 | 6.2 | 6.4 | 0.0 | 6.6 |

| Overtime | 4.0 | 0.0 | 12.4 | 8.9 | 6.0 | 8.3 |

| Total wages | 408.8 | 434.3 | 611.7 | 516.4 | 588.4 | 557.3 |

| Men | 461 | 467 | 628 | 525 | 800 | 615 |

| Women | 392 | 368 | 537 | 377 | 385 | 459 |

Source: Elaborated from International Labour Organization (ILO) (2012).

Despite the ability of this model of development to achieve an average annual growth rate in per capita gross national income of 5.5% per between 1988 and 2010,7 economic growth was accompanied by consistently high unemployment. Between 2006 and 2010, the unemployment rate was continuously above 12%, with female unemployment consistently much higher than that for men (Table 2), and the unemployment rate for graduates increased from 17 to 23%. Between 2004 and 2007 employment creation accounted for only 40.5% of new labour market entrants, and the majority of new jobs were in low-skill, labour-intensive sectors such as clothing (International Labour Organization (ILO), 2011). Indeed, throughout this period job creation failed to provide sufficient employment for the growing economically active population (Table 3), leading to a geographically uneven employment crisis. By the latter part of the first decade of the 21st century, it was increasingly apparent that the ‘exportist’ model of economic integration was not leading to inclusive development and enhanced economic security (Smith, 2014). A dual economy developed involving, on the one hand, a dynamic export-oriented industrial sector integrated into EU-oriented GVCs by either foreign investment or privileged access to EU markets, but creating largely low-skill, female, labour-intensive assembly jobs (International Labour Organization (ILO), 2011). Even in this segment of the labour market, following revisions to the Labour Code in 1996, there was also increased use of flexible temporary contracts, with lower salaries and little or no social security coverage. The International Labour Organization (ILO) (2011) estimates that 68% of employment contracts in the textile and clothing sector were of a temporary nature. On the other hand, the domestic industrial sector was focused on the relatively small internal market and struggled to provide sufficient employment opportunities to those not involved in the export economy.8 Economic growth did little to enhance the labour market situation which was characterised by lacklustre job creation, growth in low-skill jobs, declining relative wages and increasing precariousness of employment contracts (International Labour Organization (ILO), 2011, 43).

| . | 2008 . | 2010 . | 2011a . | 2012a . | 2013a . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 11.2 | 10.9 | 15.4 | 13.9 | 12.8 |

| Female | 15.9 | 18.9 | 28.2 | 24.2 | 21.9 |

| Graduates | 20.6 | 23.3 | 33.1 | 33.2 | 31.9 |

| Total | 12.4 | 13.0 | 18.9 | 16.7 | 15.3 |

| . | 2008 . | 2010 . | 2011a . | 2012a . | 2013a . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 11.2 | 10.9 | 15.4 | 13.9 | 12.8 |

| Female | 15.9 | 18.9 | 28.2 | 24.2 | 21.9 |

| Graduates | 20.6 | 23.3 | 33.1 | 33.2 | 31.9 |

| Total | 12.4 | 13.0 | 18.9 | 16.7 | 15.3 |

Note: aFourth quarter data.

Source: Elaborated from information provided by Institut National de la Statistique, Tunisia.

| . | 2008 . | 2010 . | 2011a . | 2012a . | 2013a . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 11.2 | 10.9 | 15.4 | 13.9 | 12.8 |

| Female | 15.9 | 18.9 | 28.2 | 24.2 | 21.9 |

| Graduates | 20.6 | 23.3 | 33.1 | 33.2 | 31.9 |

| Total | 12.4 | 13.0 | 18.9 | 16.7 | 15.3 |

| . | 2008 . | 2010 . | 2011a . | 2012a . | 2013a . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 11.2 | 10.9 | 15.4 | 13.9 | 12.8 |

| Female | 15.9 | 18.9 | 28.2 | 24.2 | 21.9 |

| Graduates | 20.6 | 23.3 | 33.1 | 33.2 | 31.9 |

| Total | 12.4 | 13.0 | 18.9 | 16.7 | 15.3 |

Note: aFourth quarter data.

Source: Elaborated from information provided by Institut National de la Statistique, Tunisia.

| . | 2007 . | 2008 . | 2009 . | 2010 . | 2011a . | 2012a . | 2013a . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change in economically active population | 151 | 129 | 126 | 106 | 137 | 108 | 101 |

| Job creation | 80.2 | 70.3 | 43.5 | 78.5 | 30.9 | 12.9 | 27.5 |

| Employment creation deficit | −70.8 | −58.7 | −82.5 | −27.5 | −106.1 | −95.1 | −73.5 |

| . | 2007 . | 2008 . | 2009 . | 2010 . | 2011a . | 2012a . | 2013a . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change in economically active population | 151 | 129 | 126 | 106 | 137 | 108 | 101 |

| Job creation | 80.2 | 70.3 | 43.5 | 78.5 | 30.9 | 12.9 | 27.5 |

| Employment creation deficit | −70.8 | −58.7 | −82.5 | −27.5 | −106.1 | −95.1 | −73.5 |

Note:aFourth quarter data.

Source: Elaborated from information provided by Institut National de la Statistique, Tunisia.

| . | 2007 . | 2008 . | 2009 . | 2010 . | 2011a . | 2012a . | 2013a . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change in economically active population | 151 | 129 | 126 | 106 | 137 | 108 | 101 |

| Job creation | 80.2 | 70.3 | 43.5 | 78.5 | 30.9 | 12.9 | 27.5 |

| Employment creation deficit | −70.8 | −58.7 | −82.5 | −27.5 | −106.1 | −95.1 | −73.5 |

| . | 2007 . | 2008 . | 2009 . | 2010 . | 2011a . | 2012a . | 2013a . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change in economically active population | 151 | 129 | 126 | 106 | 137 | 108 | 101 |

| Job creation | 80.2 | 70.3 | 43.5 | 78.5 | 30.9 | 12.9 | 27.5 |

| Employment creation deficit | −70.8 | −58.7 | −82.5 | −27.5 | −106.1 | −95.1 | −73.5 |

Note:aFourth quarter data.

Source: Elaborated from information provided by Institut National de la Statistique, Tunisia.

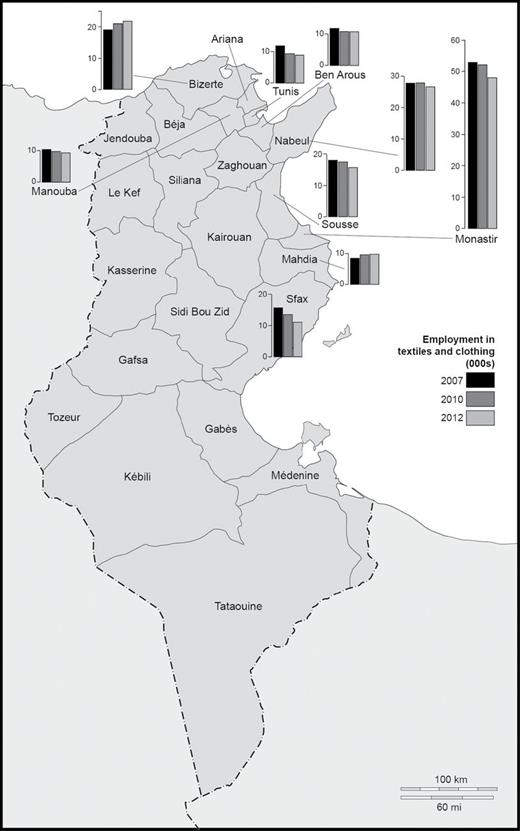

The limits of this model of ‘exportist’ development were also apparent in the resulting forms of regional uneven development. The textile and clothing industry is concentrated in nine Tunisian regions, the majority of which are located on the eastern and northern coastal zone accounting for 96% of total employment in the sector (Tizaoui, 2012) (Figure 2). The ‘exportist’ model was predicated on the geographically uneven development of the Tunisian space economy, with access to industrial sites, port and logistics facilities and major labour market pools in the coastal towns and cities each being critical to the economic geography of the industry (Tizaoui, 2012). Employment opportunities were created in this coastal zone but the consequence was that the southern and inland areas of Tunisia were relatively untouched by the ‘exportist’ model, except for remittances from workers who had migrated to the coastal zone. The consequence was that increases in unemployment were concentrated in already economically precarious regions in the south and inland regions, with much lower levels of increase apparent in many of the coastal areas (see online supplementary appendix 1).

Regional concentrations of textiles and clothing industry employment in the main production locations, Tunisia.

Source: Elaborated from API industry database.

The regional uneven development of the ‘exportist’ model was a major factor underpinning the 2011 revolution.9 As Ayeb (2011, 468) has argued “the Tunisian revolution was started not by the middle class or in the northern urban centres, but by marginalised social groups (the southern mining region workers and the unemployed, particularly graduates) from southern regions, which themselves are suffering from economic, social, and political marginalisation”. Ayeb identifies two key dimensions underpinning the Tunisian revolution: the (almost) complete nature of the Tunisian/Ben Ali regime (an absolute dictatorship with a modernist face) and the geographical unevenness of the model of development. He describes this as the “acute and systematic marginalisation of the southern, central and western regions, as opposed to the concentration of wealth and power in the north and the east of the country” (Ayeb, 2011, 469). The unfolding of the Tunisian revolution was in large part the result of the economic marginalisation of large swathes of the Tunisian space economy (Devarajan and Mottaghi, 2014), generated by the geographical concentration of GVC activity in the coastal zone. The marginalisation experienced by the populations of inland and southern Tunisia was also related to the vested interests and close connections between organised labour and the Ben Ali regime. Zemni (2013) has highlighted how the main national trade union, the Union Générale Tunisienne du Travail (UGTT), while eventually supportive of workers after the nation-wide spread of the 2011 revolution, was initially sceptical about their demands. The national UGTT acted as a transmission belt for the Ben Ali dictatorship, essentially acting to ensure social peace during a period of rapid economic liberalisation (Zemni, 2013). However, the union was also differentiated between national and local branches and between sectoral federations. The result was that while the national UGTT leadership were reluctant to support the emerging 2011 revolution in its early days, local organisations were supportive and the lack of national UGTT support became part of the impetus behind the spread of the revolution.

Economic (in)security in the Tunisian clothing sector

This section focuses on the changing experience of economic (in)security at firm and worker scales in the context of the conjunctural economic uncertainties arising from the 2011 revolution and the on-going effects of the global economic crisis in EU markets. It sheds light on the ways in which the industry at the core of the exportist model has been transformed in context of the ‘perfect storm’ of these two main forces. Both have shaped the position of firms in the clothing value chain and highlight the ways in which deep trade integration with the EU in industrial goods has created uncertainty, continuing uneven development and economic insecurity.

First, the ‘Arab Spring’ revolution transformed the economic conditions of the country. The political uncertainty generated by the end of the Ben Ali dictatorship and the lack of a government commanding legitimate political control until the 2014 elections created economic uncertainty, a precarious investment climate and sluggish economic growth. The provisional status of the post-revolutionary Tunisian state, which was reliant on a new constitution being written,10 and the struggles (sometimes violent) over political space, created somewhat of a public policy vacuum in which firms operating in GVCs had to operate. Real GDP fell by almost 2% in 2011 and inflation and the government deficit have been increasing (6 and −8.5% respectively in 2013) as pressure on prices increased, particularly for staples, and as the state continued to subsidise prices in order to prevent further social unrest (International Monetary Fund (IMF), 2014). As a consequence of state subsidies, national financial reserves have been diminishing (Devarajan and Mottaghi, 2014). Overall economic uncertainty was compounded by stagnating levels of foreign direct investment and firms were seeing increasing wage and other demands from workers resulting from heightened expectations over the benefits of liberation from dictatorship. Each of these dynamics has had significant influence on the differential ability of firms to upgrade. Second, and at the same time, the EU has continued to pursue a deep liberalisation agenda, seeking to establish closer economic relations and support for Tunisia, in return for economic liberalisation, via preparations for a Deep and Comprehensive FTA (Smith, 2015). But this deepening liberalisation agenda has taken place alongside continuing stagnation in the core EU markets for Tunisian products, notably in Italy, France and Spain. EU household consumption of textiles and clothing fell following the 2008 crisis for the first time in 7 years, and demand has remained relatively stagnant since.11

While exports to the EU fell as a result of the immediate aftermath of the 2008 global economic crisis and Multi-Fibre Arrangement (MFA) phase-out, resulting in a halving of Tunisia’s share of the EU market between 2000 and 2012, there has been a recent stabilisation of export volume in the clothing sector and increasing unit value over the entire period (see online supplementary appendix 2). Decreasing EU market share and increasing unit value can in part be attributed to the concentration on higher quality, fast fashion products, requiring proximate sourcing strategies for which Tunisian clothing manufacturers (along with those from Morocco and East-Central Europe) are well placed to contribute (Pickles and Smith, 2015; Plank et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2014). At the same time, some of the leading EU buyers relied less on higher quality upgrading and more on quick response capabilities in Tunisia: it is “easier to produce medium quality products and there was no great pressure to move up the value chain. For example [major Italian and Spanish buyers] … wanted us to continue producing their medium quality products and used Tunisia for their quick response fast fashion model.”12 It is therefore not entirely the case that Tunisia (and Morocco) can be characterised as simply a ‘pre-MFA supplier’ (Gereffi and Frederick, 2010); there is a stabilisation at around 3% of the total EU market for clothing imports, and a consolidation of activity in fast fashion value chain activity. However, new investment in the textile and clothing sector has continued to decline since 2011 and employment creation has ben uneven (see online supplementary appendix 3), as has been the case for the industrial sector as a whole following the ‘Arab Spring’ (Agence de Promotion de l'Industrie et de l'Innovation (API), 2014).

Upgrading, downgrading and economic insecurity

Firms involved in this research were concentrated in the lower to middle segments of the clothing value chain, involving full-package production (53% of firms) and CMT production (38%). This value chain position had consequences for the extent to which firms were able to pursue strategies of upgrading or to experience a worsening position in the context of the broader political-economic dynamics of revolution and crisis. Firms with full-package capabilities and own design manufacturing (ODM) activity tended to be larger than CMT firms, more than three-quarters of which had fewer than 200 employees. This predominant position of firms in the lower to middle segments of the value chain reflects the wider dominance of ready-made garment assembly and sub-contracting production determined by the requirements of EU lead firms. According to one industry association observer: “Over the past 20 years firms have wanted to move from sub-contracting to western buyers towards full-package production, but only about one-fifth of Tunisian clothing firms are able to provide full-package services and these tend to be the largest firms.”13 Indeed, full-package activity has tended to develop in firms with overseas ownership and capital.14 As one leading industry observer commented, “Tunisia’s strength is based on CMT, except in the offshore owned sector which is able to produce finished garments – this is because foreign firms have the finance and expertise to do this unlike the majority of Tunisian-owned companies.”15 The ability to pursue upgrading strategies is, therefore, closely related to having access to the capital requirements needed for such investment (see also Pickles and Smith, 2015; Smith et al., 2014). With diminishing foreign direct investment (FDI) in the context of uncertainty generated from the ‘Arab Spring’, the scope for widespread FDI-led industrial upgrading becomes constrained.

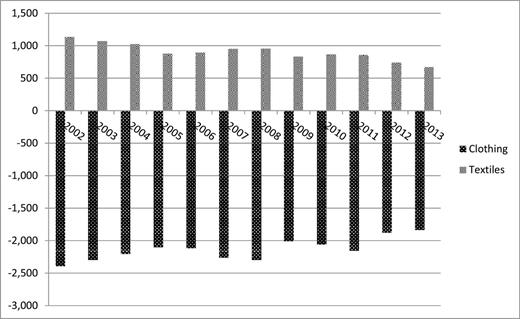

While some firms have developed full-package activity, and in some of the largest industrial clusters (such as Monastir) this has involved the expansion of value chain activity such as washing and trim suppliers, there is only limited evidence of a significant growth in textile manufacturing capacity in the Tunisian value chain. The Tunisian clothing sector remains largely dependent on the import of textile inputs for assembly into clothing. As a consequence, the EU has continued to run a large trade surplus with Tunisia in textiles and a large trade deficit in clothing (Figure 3). Pan-Euro-Mediterranean cumulation of origin rules for textile products and the trade liberalisation clauses of the 2005 Turkey-Tunisia Association Agreement have meant that some Tunisian clothing manufacturers have come to rely on the import of Turkish fabric in their production processes. As one industrial policy maker commented, “there is a limited supply chain for textile inputs in the country. This is why Tunisia signed a FTA with Turkey to ensure the supply of fabric. If fabric is imported from China the clothing product has to have at least 40% local value added [meaning from states with similar bilateral trade agreements] to get duty free access to the EU”,16 leading some of the largest full-package manufacturers to establish strategic alignments with Turkish firms to supply fabric for assembly in Tunisia.17

EU-Tunisia trade balance in textiles and clothing (million Euros).

Source: Elaborated from Comext.

Within this context of limited textile capabilities and relative dependence on EU and Turkish suppliers, to what degree have Tunisian-based clothing firms been able to upgrade activity and with what impact on the economic security of firms and workers operating in GVCs following the ‘Arab Spring’ and economic crisis? There is an apparent bifurcation in the ability of Tunisian-based firms to increase production since the ‘Arab Spring’: two-thirds of firms involved in this research had been able to increase the value of production, while just over one-quarter (28%) experienced a decline. The ability of firms to generate increases in production is related to their position in the value chain, with a larger proportion of full-package/ODM18 than CMT firms experiencing increasing production and a larger proportion of CMT firms experiencing a decrease in production (see online supplementary appendix 4). This is suggestive of a process of concentration of opportunity among lead firms within Tunisia, potentially resulting in the marginalisation of firms lower down the clothing value chain.

Functional upgrading in the clothing value chain was more limited than other forms of upgrading. Since the ‘Arab Spring’ the majority of firms reported that they had not implemented a change in the balance of functions in the value chains in which they operated largely because of the uncertain investment environment in Tunisia and market opportunities in the EU. Those firms which had introduced functional changes (38% of firms) reported that they had introduced enhanced design, marketing and procurement activity. Only one CMT firm reported an upgrading of its functional position (increased procurement activity), indicating that the primary focus of functional upgrading has been taking place in larger full-package and ODM firms, with greater financial and managerial capacity. Those firms that had enhanced functional capabilities tended to experience a greater likelihood of increased employment and production than those firms which had not experienced functional upgrading, highlighting the significance of functional upgrading for overall firm-level economic security compared to other forms of upgrading (see below). The limited extent of functional upgrading in firms lower down the value chain reflects the challenges and limited financial resources available to such firms, constraining their ability to enhance their economic security. In the context of an overall limited access to firm finance and the uncertainties arising from the ‘Arab Spring’ (International Labour Organization (ILO), 2011), few firms had the resources to invest in functional upgrading and those with foreign investment were often wary of further commitments. Limited functional upgrading thereby constrained the enhancement of the economic security of firms even in this key export sector.

Product upgrading was more common; three-quarters had implemented enhancements to the quality of the products, mainly involving the diversification of product mix and increased quality. These changes reflect the more exacting requirements of EU buyers looking for enhanced product quality in increasingly tight market environments in the EU. Product upgrading was not, however, differentiated by value chain position, with both CMT and full-package firms involved in product improvements and diversification. However, there was little evidence of a relationship between product upgrading and the increased economic security of firms when firms implementing product upgrading were compared to those firms which were not engaged in product upgrading.19 Product upgrading did, however, enable firms which were in potentially more vulnerable value chain positions to sustain their position during an uncertain political and economic period. Product upgrading thus became a mechanism for sustaining a status quo market share, even if it has not translated into widespread employment and productivity gains and enhanced economic security.

Process upgrading was by far the most ubiquitous form of upgrading: virtually all firms had implemented some form of process upgrading in the last 4 years. Reflecting the increased and more exacting requirements of EU buyers, process upgrading was dominated by increased quality control activity.20 Almost 60% of those firms implementing process upgrading also reported an increase in employment and 69% of firms involved in process upgrading saw an increase in the value of production. Process upgrading and the production efficiencies that were derived were linked to increasing demand from buyers in the EU for decreased turn-around time and time to delivery, and enhanced product quality (see Tokatli, 2008). As a consequence, process improvements largely enabled clothing firms to retain production and employment levels in the face of increasing external pressures and political-economic uncertainty. However, production flexibility derived from sub-contracting was one mechanism by which firm-level risk was transferred down the value chain to sub-contractors, which were often in a more precarious position with regard to employment security.

The uncertain political-economic environment generated by the ‘Arab Spring’ and market uncertainty in the EU were clearly impacting on firms, with the relationship between employment change and social upgrading through employment generation differentiated by the value chain position of Tunisian clothing firms. Among CMT firms, employment change was bifurcated between employment growth and decline, while full-package producers were much more likely to have experienced employment growth since the ‘Arab Spring’ (see online supplementary appendix 5). The relative balance of firms seeing employment decline between CMT and full-package firms highlights the differentiated nature of social downgrading almost regardless of apparent value chain position. However, a key dimension in the economic security of workers in Tunisia is the increasing use of flexible employment contracts (International Labour Organization (ILO), 2011). Clothing firms made extensive use of such forms of contract, enabled via earlier revisions to the Labour Code. Around half of firms, regardless of their value chain position, employed workers on non-permanent contracts, and among both CMT and full-package firms the majority used non-permanent staff, allowing them to manage short-term orders (a direct outcome of the fast fashion model (Plank et al., 2012; Tokatli, 2008)), and to deal with the unpredictability and changing nature of contracts with lead firms by ensuring production flexibility and reducing risk (Plank et al., 2012). This reflects increasing pressure from lead firms to reduce time to delivery, with associated higher levels of uncertainty for manufacturers. As a consequence, risk and precarity increased for workers employed on a non-permanent basis, especially within the context of the overall employment and increasing cost of living crises in Tunisia.

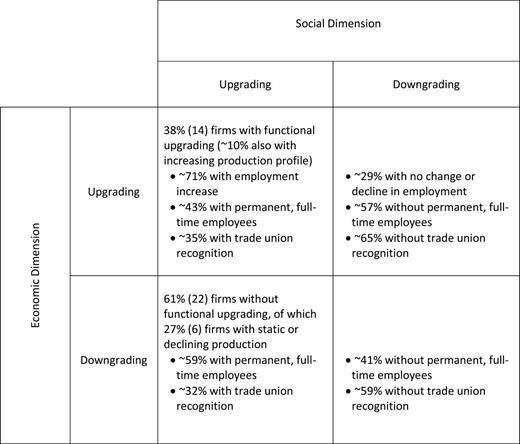

Wage pressure was one of the major challenges faced by many firms, regardless of the presence of trade unions, reflecting the changed set of social and worker expectations over remuneration since 2011. Virtually all firms experienced average wage growth of just over 16% since the ‘Arab Spring’. This mirrored the national rate of wage increase and reflected the increasing demands of workers in the post-revolutionary context. Firm managers argued that worker demands had been particularly exacting, reflecting higher social expectations in the turmoil of the post-revolutionary period, as well as the need on the part of firm managers to ensure some workforce stability. Wage pressure reflects less the role of factory-level trade unions and more the implementation of industry collective agreements, which took place in the context of post-revolutionary agreements with the main union confederation, UGTT, for a 4.7% wage increase in late 2011.21 One way in which firm managers in the clothing sector managed increasing wage pressure was through the provision of various in-kind wage benefits including transportation and food subsidies, which as a proportion of total salary were higher in the clothing sector than the national average (Table 1). Wage increases in the industry also occurred in the context of contract price squeezing by EU lead firms, reflecting market pressures in the EU, with two-thirds of firms experiencing pressure from buyers to reduce contract prices. Consequently, many clothing firms in Tunisia were being squeezed from two sides; tighter contracting terms from EU lead firms and higher post-revolutionary wage demands and requirements from workers. The widening national budget deficit, sluggish economic growth, rapidly increasing prices for basic goods, increasing unemployment since the revolution (15.3% in the last quarter of 2013), and—given the predominance of female labour in the clothing industry—the worsening ratio of female to male unemployment between 2009 and 2013 (female unemployment in 2013 was 21.9%) are together seriously challenging the economic security of workers.22 This two-fold pressure is clearly impacting on the economic security of firms and workers in the clothing sector. Figure 4 brings together these dimensions of upgrading/downgrading and (in)security, and provides an estimated distribution of firms involved in this research across this matrix. The experience in the post-‘Arab Spring’ context is therefore highly differentiated even in the heartland of the coastal industrial zone. On the one hand, there were a number of firms who were pursuing a ‘high-road’ growth path, some seeing employment growth, but most exhibiting the characteristics of firms which were socially downgrading in that they did not make use of permanent, full time employment and did not have trade union recognition. This reflects the presence of mainly full-package firms in these segments, the majority of which were involved in the employment of non-permanent, temporary workers. Consequently, they could be described as pursuing a growth strategy with ‘low-road’ characteristics; attempting to enhance the economic security of the firm in their respective value chain, regardless of the consequences for the economic security of workers. However, the majority of firms occupied a middle ground of relative stasis making them vulnerable to changes in value chain and contracting environments. There were also a number of firms experiencing economic downgrading, of which there was an approximate balance between those which could be said to be seeing social upgrading and social downgrading. The future for these firms appears to be very precarious.

Economic and social upgrading/downgrading in the Tunisian clothing industry.

Conclusion

Dabashi (2012) has argued that the ‘Arab Spring’ revolutions created a ‘new liberation geography’ for the Arab world, one in which the postcolonial condition of authoritarian rule combined with economic liberalisation could finally be shaken off. Without doubt the ‘Arab Spring’ enabled important political gains in Tunisia. However, the 4 years following the ‘Arab Spring’ have also resulted in a highly contested and fractious politics which has led to a relatively unstable political-economic climate. Consequently, it is less than clear that a new pathway to greater economic security has been established. In the context of the continuing political-economic uncertainty, alongside the continuing market uncertainty in the EU, the trajectories of the key export sector of clothing have been highly differentiated. Developments in the industry appear not to have resolved the contradictions of a relatively low-value, geographically concentrated and spatially polarised model of export-oriented development. It is clear that clothing firms, while adopting a range of measures to attempt to upgrade their export production, are doing so in the context of tremendous cost pressures from two directions; workers’ demands and ability to leverage enhanced wage levels, and the requirements of buyers for tightening contract prices and delivery times. This is reflected in the increasing use of flexible employment contracts in the clothing sector; a primary mechanism used to manage some of these contradictory pressures. However, this is doing little to resolve the continued spatial disparity in the Tunisian space-economy between the coastal export zones and the marginalised interior; creating conditions for further socio-economic insecurity for workers both within and beyond the primary export sectors such as clothing.

Consequently, the relationship between trade liberalisation, the FTA and economic security in GVCs continues to be a problematic one in the Tunisian context. Employment opportunities are critical to the major GVC sectors in Tunisia, but post-‘Arab Spring’ experience continues to underline the geographical inequalities resulting from the exportist model and the nature of jobs created. Equally, in the face of the wage pressures experienced by firms and the tightening contracting regimes operated by EU buyers as core markets remain largely static, the ability of GVC-oriented sectors such as clothing to find a complementary pathway between economic and social upgrading and towards enhanced economic security for all firms and workers remains in question. Conceptually, understanding these political-economic dynamics requires a widening of the focus of GVC research on upgrading to consider the more differentiated experience of export sectors and to raise fundamental questions over the ability of GVCs to enhance economic security in an increasingly inter-dependent world economy. Tunisia’s integration into GVCs has enabled significant growth of firms in the coastal zone. However, the limited extent to which deep value chain embeddedness is taking place within Tunisia and the constrained degree to which the industry has been able to move away from relatively low-wage assembly work suggest that this model may have begun to reach its limits, brought to the fore through the two dynamic pressures arising from political-economic uncertainty associated with the ‘Arab Spring’ and market stagnation and economic crisis in EU economies. Indeed, these two key dynamics have highlighted the need for analyses of GVC integration to take seriously the dimensions of insecurity, not only those of upgrading, which have been the focus of the more mainstream literature and policy analysts. Recognising the diversity of firm and employment outcomes driven by a range of complex political-economic forces—from wage struggles by workers to the increasingly exacting demands of EU buyers—allows an analysis of how the experience of firms and workers may in part be one of increasing insecurity, rather than one just involving upgrading and development. Analyses of GVC integration should therefore be attentive to the differentiated employment and firm-level effects arising from how production and labour regimes articulate (Azmeh, 2014), and policy models are required which enable more inclusive, less uncertain modes of economic integration to be formulated.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at CAMRES Journal online.

Acknowledgements

The paper arises from research funded by the British Academy for a project entitled “Europe and North Africa after the ‘Arab Revolts’: Economic Integration and Uneven Development” (SG111852), and from a Queen Mary-Warwick University collaborative project ‘The Externalisation of European Union Economic Governance’. I am very grateful to Irène Carpentier, Sylvie Daviet, Vincent Guermond and Hamadi Tizaoui for assistance with the research; to Liam Campling, James Harrison and Ben Richardson for their input on the collaborative project and to Ed Oliver for producing several of the figures. A previous version of this paper was presented at the Centre for the Study of Global Security and Development workshop on ‘Economic (In)Security and the Global Economy’ at Queen Mary University of London, March 2013. I am grateful to participants at the workshop for the comments on that version of the paper and to the journal’s reviewers, editors and guest editors for their helpful comments on an earlier version.

Endnotes

See Pickles and Smith (2015) for a wider conceptualisation of conjunctural economic geography approaches to GVC analysis.

Defined in terms of overall volume of employment, worker representation, wage improvements and so on.

The 1976 agreement was signed alongside similar agreements with Morocco and Algeria. For Tunisia, it represented a development of the 1969 association arrangement with the EEC.

The Barcelona Process and the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership provided a macro-regional co-operation framework for EU-North African integration. Following the 2004 enlargements of the EU, there was a shift towards more bilateral arrangements (the European Neighbourhood Policy) (Del Sarto and Schumacher, 2005). Within the sphere of trade policy, however, the extensive liberalisation for manufactured goods was already established as part of the 1998 EU-Tunisia FTA, and was relatively unaffected by this shifting policy focus.

Employment data from May 2014, elaborated from http://www.tunisieindustrie.nat.tn/en/tissu.asp. Trade data calculated from Comext.

Interview with Tunisian clothing industry association, Tunis, December 2012.

Calculated from World Bank data.

Daviet (2013) has also pointed to the recent development of offshore Tunisian firms elsewhere in Africa.

Uneven development and lack of inland employment opportunities have also been key factors in stimulating attempts at out-migration from Tunisia, regulated by the wider attempts of the EU to reduce ‘illegal’ and undocumented migration flows and the related motivation to externalise border management via agencies such as Frontex (Casas-Cortes et al., 2013, Reid-Henry, 2013).

Following protracted political bargaining and discussion a new constitution was finally adopted in early 2014 leading to parliamentary and presidential elections later in 2014.

Interview with senior personnel, EURATEX, Brussels, July 2012.

Interview with independent industrial association, Tunis, December 2012.

Interview with Tunisian clothing industry association, Tunis, December 2012.

Over half of firms involved in this research involved foreign investment, of which the majority (55%) involved French partners.

Interview with independent industrial association, Tunis, December 2012.

Interview with head of foreign investment agency, November 2012.

Interview with Tunisian clothing industry association, Tunis, December 2012. See Tokatli and Kızılgün (2010) for a wider discussion of Turkish-North African clothing production.

Due to the small number of firms with ODM capability (three firms) this group are included alongside those with full-package capabilities in this analysis. The rationale for this grouping is that, while there are differences between the capabilities of such firms, each type also demonstrates an enhanced level of manufacturing capability compared to those with CMT operations.

Both the majority firms improving their product profile and those not involved in product upgrading reported increased levels of employment and production since 2010.

Other significant process upgrading took place through new manufacturing technologies (75% of firms), enhanced internal production organisation (66% of firms), mainly involving a higher degree of technology intensive production systems, closer control of labour productivity, and the fragmentation of line production systems to cope with smaller batch size of orders, and increased sub-contracting (66% of firms), amounting to one-quarter of the value of production.

This agreement was widely regarded as a means to quell continuing social unrest and has been accompanied by an 11% increase in May 2014 in the national minimum wage, which effects low paid workers in labour-intensive sectors such as clothing.

Unemployment data calculated from data available via the Institut National de la Statistique—Tunisie.

References