-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Anna R Yousaf, Lindsey M Duca, Victoria Chu, Hannah E Reses, Mark Fajans, Elizabeth M Rabold, Rebecca L Laws, Radhika Gharpure, Almea Matanock, Ashutosh Wadhwa, Mary Pomeroy, Henry Njuguna, Garrett Fox, Alison M Binder, Ann Christiansen, Brandi Freeman, Christopher Gregory, Cuc H Tran, Daniel Owusu, Dongni Ye, Elizabeth Dietrich, Eric Pevzner, Erin E Conners, Ian Pray, Jared Rispens, Jeni Vuong, Kim Christensen, Michelle Banks, Michelle O’Hegarty, Lisa Mills, Sandra Lester, Natalie J Thornburg, Nathaniel Lewis, Patrick Dawson, Perrine Marcenac, Phillip Salvatore, Rebecca J Chancey, Victoria Fields, Sean Buono, Sherry Yin, Susan Gerber, Tair Kiphibane, Trivikram Dasu, Sanjib Bhattacharyya, Ryan Westergaard, Angela Dunn, Aron J Hall, Alicia M Fry, Jacqueline E Tate, Hannah L Kirking, Scott Nabity, A Prospective Cohort Study in Nonhospitalized Household Contacts With Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Infection: Symptom Profiles and Symptom Change Over Time, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 73, Issue 7, 1 October 2021, Pages e1841–e1849, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1072

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Improved understanding of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) spectrum of disease is essential for clinical and public health interventions. There are limited data on mild or asymptomatic infections, but recognition of these individuals is key as they contribute to viral transmission. We describe the symptom profiles from individuals with mild or asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection.

From 22 March to 22 April 2020 in Wisconsin and Utah, we enrolled and prospectively observed 198 household contacts exposed to SARS-CoV-2. We collected and tested nasopharyngeal specimens by real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) 2 or more times during a 14-day period. Contacts completed daily symptom diaries. We characterized symptom profiles on the date of first positive rRT-PCR test and described progression of symptoms over time.

We identified 47 contacts, median age 24 (3–75) years, with detectable SARS-CoV-2 by rRT-PCR. The most commonly reported symptoms on the day of first positive rRT-PCR test were upper respiratory (n = 32 [68%]) and neurologic (n = 30 [64%]); fever was not commonly reported (n = 9 [19%]). Eight (17%) individuals were asymptomatic at the date of first positive rRT-PCR collection; 2 (4%) had preceding symptoms that resolved and 6 (13%) subsequently developed symptoms. Children less frequently reported lower respiratory symptoms (21%, 60%, and 69% for <18, 18–49, and ≥50 years of age, respectively; P = .03).

Household contacts with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection reported mild symptoms. When assessed at a single timepoint, several contacts appeared to have asymptomatic infection; however, over time all developed symptoms. These findings are important to inform infection control, contact tracing, and community mitigation strategies.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus responsible for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), continues to cause significant morbidity and mortality worldwide [1, 2]. Rapid recognition of COVID-19 symptoms is vital for timely clinical diagnosis and management, and for public health interventions such as contact tracing activities and infection prevention and control measures. Understanding the frequency of asymptomatic infections in the community setting is also important to inform mitigation efforts focused on reducing viral transmission.

As the COVID-19 pandemic progresses, our understanding of the clinical spectrum of COVID-19 is quickly evolving. However, the majority of our current information on the clinical presentation of COVID-19 comes from patients requiring hospitalization [3–5] and from special populations such as those in outbreak investigations (eg, cruise ships) that only capture symptom information at a single point in time [6–9] and in long-term care facilities [10]. While the clinical characteristics and symptoms of individuals with more severe COVID-19 have been described, there remains relatively little detailed information on the natural progression of clinical and symptom profiles for individuals with mild illness, or people with no symptoms but with laboratory evidence of infection. Here we describe a cohort of household members (hereafter referred to as household contacts) who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 following exposure to someone else in their home with laboratory-confirmed infection. We describe their demographic and clinical characteristics, time from exposure to symptom onset, symptom profiles, and the evolution of symptoms over time.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

Individuals with COVID-19 identified through routine public health surveillance and their household contacts were enrolled in a household transmission investigation. We enrolled households from 22 March to 22 April 2020, in the Milwaukee, Wisconsin and Salt Lake City, Utah metropolitan areas, as described in detail (Lewis et al, unpublished data). Only the household contacts of source individuals were included as the study population for this analysis; no household contacts were hospitalized prior to or during the 14-day study period.

Data Collection and Confirmatory Testing

We interviewed household contacts using a standardized questionnaire to obtain demographic and clinical characteristics, along with detailed symptoms that contacts may have experienced prior to enrollment as well as symptoms experienced on the day of enrollment. On the first day of the study period (day 0, ie, day of enrollment), we collected nasopharyngeal (NP) swab specimens from all 198 enrolled household contacts. We observed household contacts for 14 days following enrollment and requested that they record daily measured temperatures and symptoms in a symptom diary. On day 14 (the final close-out visit), we returned to the household and collected NP swab specimens from all household members and retrieved the daily symptom diaries. During the 14-day follow-up, an investigation team returned to the household for interim NP swab collections from all household contacts if any previously asymptomatic household contact developed new symptoms. We tested NP specimens using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2019-Novel Coronavirus Real-Time Reverse-Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (rRT-PCR) Panel [11]. Contacts with SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed by rRT-PCR on at least 1 NP were included in this analysis.

Analyses

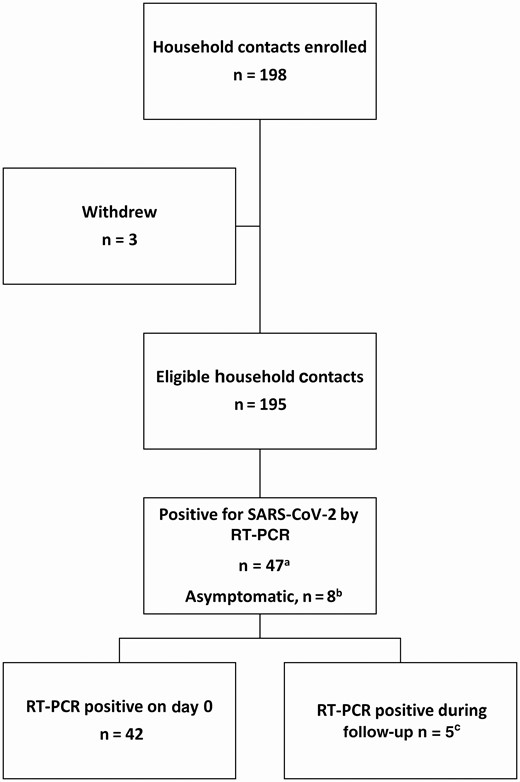

We assessed symptoms reported by household contacts on the collection date of their first rRT-PCR–positive NP specimen (Figure 1, subset A), and categorized symptoms as constitutional (fever, chills, myalgia, or fatigue), upper respiratory (runny nose, nasal congestion, or sore throat), lower respiratory (cough, difficulty breathing, shortness of breath, wheezing, or chest pain), neurologic (headache, loss of taste, or loss of smell), and gastrointestinal (nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, or abdominal pain). We calculated proportions for each category of symptoms and stratified these proportions by sex, age, race, ethnicity, and presence of self-reported underlying medical conditions. Underlying medical conditions included diabetes mellitus, immunocompromising conditions, and any chronic lung, cardiovascular, kidney, liver, neurologic, or other chronic disease. We also evaluated the co-occurrence of various symptom combinations. Differences between groups were assessed using Fisher exact test.

Flowchart for household contacts enrolled in the study, by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) testing results. aSubset A. bSubset B. cSubset C. (Please see “Analyses” in the Methods for descriptions of the subsets.)

We identified and prospectively followed household contacts who were asymptomatic at the time they initially tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by PCR (Figure 1, subset B) to see if they developed symptoms during the study period. We also reviewed symptom data to identify any prior symptoms.

To examine evolution of symptoms over time, we described in detail the symptom diaries of a subset of household contacts who were negative on enrollment (day 0) but tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 during the 2-week longitudinal follow-up period (Figure 1, subset C). Limiting this part of the analysis to this subset of positive contacts ensured their reported symptoms were likely due to acute COVID-19 and allowed for a granular description of day-by-day symptom evolution.

We used a survival function to estimate the median days from exposure, defined as symptom onset in household source cases, to symptom onset in the corresponding household contacts. We performed analyses using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) and RStudio version 1.1.453 (RStudio Inc, Boston, Massachusetts). This protocol was reviewed by CDC human subjects research officials and the activity was deemed nonresearch as part of the COVID-19 public health response.

RESULTS

Of the 198 contacts enrolled, 3 withdrew, 47 tested rRT-PCR positive at 1 or more sample collections, and 148 remained negative during follow-up (Figure 1). We included the 47 household contacts with an rRT-PCR–positive NP specimen in this analysis. Forty-two contacts (89%) were rRT-PCR positive on day 0, and 5 (11%) changed from rRT-PCR negative on day 0 to rRT-PCR positive during follow-up. All household contacts (n = 198 [100%]) had complete symptom diary information on the collection date of first positive rRT-PCR, and most rRT-PCR–positive household contacts (n = 37/47 [79%]) had complete symptom diary information from the entire observation period.

Of the 47 household contacts with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by rRT-PCR, the majority were female (n = 29 [62%]), white (n = 35 [74%]), non-Hispanic (n = 42 [89%]), and with a variable age distribution: <18 years (n = 14 [30%]); 18–49 years (n = 20 [43%]); 50–64 years (n = 10 [21%]); and ≥65 years (n = 3 [6%]). Half (n = 24 [51%]) of the household contacts with SARS-CoV-2 had an underlying medical condition, with the most prevalent conditions being any chronic lung disease (n = 9 [19%]) and any cardiovascular disease (n = 6 [13%]) (Table 1). The proportion of contacts with 1 or more underlying medical condition increased with age (<18 years: n = 4/14 [29%]; 18–49 years: n = 11/20 [55%]; 50–64 years: n = 6/10 [60%]; ≥65 years: n = 3/3 [100%]).

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Household Contacts Whose Nasopharyngeal Specimens Tested Positive or Negative for Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 by Polymerase Chain Reactiona

| Characteristic . | SARS-CoV-2 rRT-PCR Positive (n = 47) . | SARS-CoV-2 rRT-PCR Negative (n = 148) . |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 18 (38) | 78 (53) |

| Female | 29 (62) | 70 (47) |

| Age category, y | ||

| <18 | 14 (30) | 55 (37) |

| 18–49 | 20 (43) | 69 (47) |

| 50–64 | 10 (21) | 19 (13) |

| ≥65 | 3 (6) | 5 (3) |

| Race | ||

| White | 35 (74) | 109 (74) |

| Black/African American | 4 (9) | 22 (15) |

| Asian | 4 (9) | 10 (7) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1 (2) | 3 (2) |

| Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander | 0 (0) | 2 (1) |

| Multiracial | 3 (6) | 1 (1) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic | 42 (89) | 121 (82) |

| Hispanic | 5 (11) | 27 (18) |

| State of residence | ||

| Utah | 31 (66) | 100 (68) |

| Wisconsin | 16 (34) | 48 (32) |

| Any underlying medical conditionb | 24 (51) | 39 (26) |

| Any chronic lung disease | 9 (19) | 26 (18) |

| Any cardiovascular disease | 6 (13) | 14 (9) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 4 (9) | 2 (1) |

| Any chronic kidney disease | 1 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Any chronic liver disease | 1 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Any immunocompromising condition | 2 (4) | 1 (1) |

| Other | 6 (13) | 4 (3) |

| Characteristic . | SARS-CoV-2 rRT-PCR Positive (n = 47) . | SARS-CoV-2 rRT-PCR Negative (n = 148) . |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 18 (38) | 78 (53) |

| Female | 29 (62) | 70 (47) |

| Age category, y | ||

| <18 | 14 (30) | 55 (37) |

| 18–49 | 20 (43) | 69 (47) |

| 50–64 | 10 (21) | 19 (13) |

| ≥65 | 3 (6) | 5 (3) |

| Race | ||

| White | 35 (74) | 109 (74) |

| Black/African American | 4 (9) | 22 (15) |

| Asian | 4 (9) | 10 (7) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1 (2) | 3 (2) |

| Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander | 0 (0) | 2 (1) |

| Multiracial | 3 (6) | 1 (1) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic | 42 (89) | 121 (82) |

| Hispanic | 5 (11) | 27 (18) |

| State of residence | ||

| Utah | 31 (66) | 100 (68) |

| Wisconsin | 16 (34) | 48 (32) |

| Any underlying medical conditionb | 24 (51) | 39 (26) |

| Any chronic lung disease | 9 (19) | 26 (18) |

| Any cardiovascular disease | 6 (13) | 14 (9) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 4 (9) | 2 (1) |

| Any chronic kidney disease | 1 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Any chronic liver disease | 1 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Any immunocompromising condition | 2 (4) | 1 (1) |

| Other | 6 (13) | 4 (3) |

Data are presented as no. (%).

Abbreviations: rRT-PCR, real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

aData collection in Wisconsin and Utah household contact cohort, 22 March–22 April 2020.

bAny chronic lung disease: asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or other chronic lung disease; any cardiovascular disease: hypertension, coronary artery disease/myocardial infarction, or other cardiovascular disease; any chronic kidney disease: end-stage renal disease, renal insufficiency, or other kidney disease; any liver disorder: nonalcoholic fatty liver disease or other chronic liver condition; any immunocompromising condition: human immunodeficiency virus, cancer, or other immunosuppressive condition; and any other chronic condition: anemia, psoriasis, thyroid disorder.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Household Contacts Whose Nasopharyngeal Specimens Tested Positive or Negative for Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 by Polymerase Chain Reactiona

| Characteristic . | SARS-CoV-2 rRT-PCR Positive (n = 47) . | SARS-CoV-2 rRT-PCR Negative (n = 148) . |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 18 (38) | 78 (53) |

| Female | 29 (62) | 70 (47) |

| Age category, y | ||

| <18 | 14 (30) | 55 (37) |

| 18–49 | 20 (43) | 69 (47) |

| 50–64 | 10 (21) | 19 (13) |

| ≥65 | 3 (6) | 5 (3) |

| Race | ||

| White | 35 (74) | 109 (74) |

| Black/African American | 4 (9) | 22 (15) |

| Asian | 4 (9) | 10 (7) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1 (2) | 3 (2) |

| Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander | 0 (0) | 2 (1) |

| Multiracial | 3 (6) | 1 (1) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic | 42 (89) | 121 (82) |

| Hispanic | 5 (11) | 27 (18) |

| State of residence | ||

| Utah | 31 (66) | 100 (68) |

| Wisconsin | 16 (34) | 48 (32) |

| Any underlying medical conditionb | 24 (51) | 39 (26) |

| Any chronic lung disease | 9 (19) | 26 (18) |

| Any cardiovascular disease | 6 (13) | 14 (9) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 4 (9) | 2 (1) |

| Any chronic kidney disease | 1 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Any chronic liver disease | 1 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Any immunocompromising condition | 2 (4) | 1 (1) |

| Other | 6 (13) | 4 (3) |

| Characteristic . | SARS-CoV-2 rRT-PCR Positive (n = 47) . | SARS-CoV-2 rRT-PCR Negative (n = 148) . |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 18 (38) | 78 (53) |

| Female | 29 (62) | 70 (47) |

| Age category, y | ||

| <18 | 14 (30) | 55 (37) |

| 18–49 | 20 (43) | 69 (47) |

| 50–64 | 10 (21) | 19 (13) |

| ≥65 | 3 (6) | 5 (3) |

| Race | ||

| White | 35 (74) | 109 (74) |

| Black/African American | 4 (9) | 22 (15) |

| Asian | 4 (9) | 10 (7) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1 (2) | 3 (2) |

| Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander | 0 (0) | 2 (1) |

| Multiracial | 3 (6) | 1 (1) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic | 42 (89) | 121 (82) |

| Hispanic | 5 (11) | 27 (18) |

| State of residence | ||

| Utah | 31 (66) | 100 (68) |

| Wisconsin | 16 (34) | 48 (32) |

| Any underlying medical conditionb | 24 (51) | 39 (26) |

| Any chronic lung disease | 9 (19) | 26 (18) |

| Any cardiovascular disease | 6 (13) | 14 (9) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 4 (9) | 2 (1) |

| Any chronic kidney disease | 1 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Any chronic liver disease | 1 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Any immunocompromising condition | 2 (4) | 1 (1) |

| Other | 6 (13) | 4 (3) |

Data are presented as no. (%).

Abbreviations: rRT-PCR, real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

aData collection in Wisconsin and Utah household contact cohort, 22 March–22 April 2020.

bAny chronic lung disease: asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or other chronic lung disease; any cardiovascular disease: hypertension, coronary artery disease/myocardial infarction, or other cardiovascular disease; any chronic kidney disease: end-stage renal disease, renal insufficiency, or other kidney disease; any liver disorder: nonalcoholic fatty liver disease or other chronic liver condition; any immunocompromising condition: human immunodeficiency virus, cancer, or other immunosuppressive condition; and any other chronic condition: anemia, psoriasis, thyroid disorder.

In Figure 2 we present symptoms reported on the date of first positive rRT-PCR result and symptoms reported throughout the illness for the 47 rRT-PCR–positive household contacts (see Supplementary Table for more detail). The most commonly reported symptom categories on the date of first positive rRT-PCR were upper respiratory (n = 32 [68%]) followed by neurologic (n = 30 [64%]). For symptoms experienced throughout the illness, the percentage of household contacts reporting neurologic symptoms increased to 94% (n = 44), predominated by headache (n = 41 [87%]), followed by upper respiratory symptoms (n = 42 [89%]). Nasal congestion and runny nose were the most commonly reported upper respiratory symptoms at both date of first positive rRT-PCR test (n = 17 [47%] and n = 39 [83%], respectively) and throughout the illness (n = 20 [43%] and n = 32 [68%], respectively). Less than half (n = 20 [43%]) of household contacts reported cough at date of the first positive rRT-PCR, which increased to 74% (n = 35) reported at any time throughout the illness. A similar pattern was observed for difficulty breathing (n = 5 [11%] at date of first positive rRT-PCR and n = 19 [40%] reported any time). Only 19% (n = 9) of household contacts reported subjective or objective fever at date of first positive rRT-PCR, although just over half (n = 25 [53%]) reported experiencing a fever at any time during the illness. Less than a quarter (n = 11 [23%]) of household contacts reported gastrointestinal symptoms at date of first positive rRT-PCR, whereas more than half reported having experienced gastrointestinal symptoms at any time (n = 25 [53%]). On the date of first positive rRT-PCR, 8 (17%) household contacts had no symptoms. Of these 8 individuals, 2 (4%) individuals were postsymptomatic (prior symptoms had resolved by collection date of first positive PCR); the remaining 6 (13%) individuals were presymptomatic (ie, developed symptoms during the follow-up observation period).

![Coronavirus disease 2019 symptoms reported by household contacts (n = 47) on the date of first positive severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) test compared to symptoms reported throughout the illness. Nasal congestion variable was present for 36 of 47 symptom diaries (denominator n = 36 for these estimates). bLoss of smell: partial (n = 7 [50%]) and complete (n = 7 [50%]). cLoss of taste: partial (n = 9 [64%]) and complete (n = 5 [36%]). dCough: dry (n = 12 [60%]) and productive (n = 8 [40%]). eSubjective and objective.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/cid/73/7/10.1093_cid_ciaa1072/1/m_ciaa1072f0002.jpeg?Expires=1749818061&Signature=tYF0W4AvkfqxlYjvXVNrv-oYOrpSe6tnk44vSxiaj13xCeckRNoXicdgto3dB56~pEzPOLpNFmZqiH9~8ZsA31pkjG041rkrBEHH7OMXKGbTapSJCYdpCRBfnvNYFJ~MoiX~-FGNyXmnYC4A45EFFId8go1qRKTNNFML1WQiAjKADQ5vuRxILzRHciK86ow4bWlg~qLtivffBpf6ZEfrTDwUhPrJl9UWXFjCV5zgG55yh-AaK7pKzjV3DwKTqc3egNgsuUaQpgMc5M56L1gcWsCZuM8c~ZLC6iYDy1W0e7xfUhNm8~SDyfKgapecrnrZecSy8twSthxwWxOnHwxuQA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Coronavirus disease 2019 symptoms reported by household contacts (n = 47) on the date of first positive severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) test compared to symptoms reported throughout the illness. Nasal congestion variable was present for 36 of 47 symptom diaries (denominator n = 36 for these estimates). bLoss of smell: partial (n = 7 [50%]) and complete (n = 7 [50%]). cLoss of taste: partial (n = 9 [64%]) and complete (n = 5 [36%]). dCough: dry (n = 12 [60%]) and productive (n = 8 [40%]). eSubjective and objective.

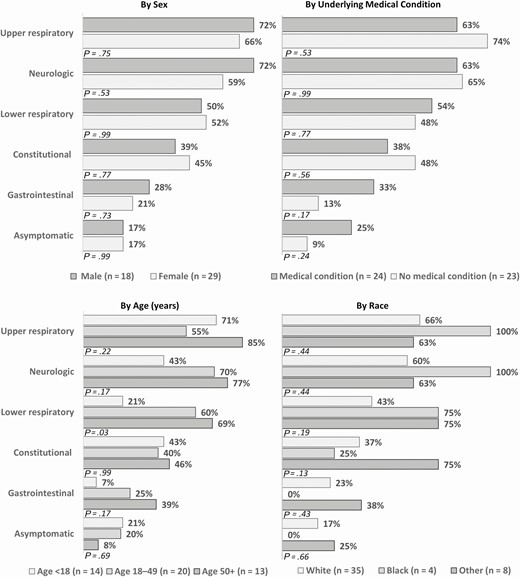

Symptoms on the date of first positive rRT-PCR stratified by sex, age, comorbidity status, and race are shown in Figure 3 (and in more detail in Supplementary Table). A majority of both sexes reported upper respiratory or neurologic symptoms with no statistically significant differences found between the sexes. Similarly, contacts with and without underlying medical conditions most commonly reported upper respiratory or neurologic symptoms with no significant differences between the 2 groups. Among the different age groups, the most common symptoms were as follows: upper respiratory symptoms in children <18 years (n = 10 [71%]), neurologic symptoms in adults 18–49 years (n = 14 [70%]), and upper respiratory symptoms in adults 50 years or older (n = 11 [85%]). There was a significant difference in the percentage of household contacts reporting lower respiratory symptoms with increasing age (21%, 60%, and 69% for ages <18, 18–49, and ≥50 years, respectively; Fisher exact P = .03).

Coronavirus disease 2019 symptoms reported by household contacts on the date of first positive severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction test, stratified by sex, age, underlying medical condition, and race (n = 47). Constitutional: fever, chills, muscle aches, fatigue. Upper respiratory: runny nose, nasal congestion, sore throat. Lower respiratory: cough, discomfort in chest, shortness of breath, wheezing, chest pain. Neurologic: headache, loss of taste, loss of smell. Gastrointestinal: nausea, diarrhea, abdominal pain. Other race: American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, other. P values were calculated using Fisher exact test.

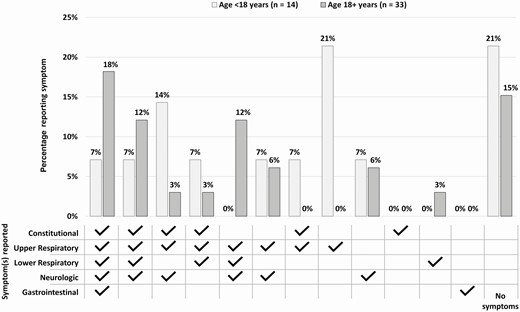

Co-occurrence of the symptoms reported on the date of first positive rRT-PCR is displayed in Figure 4. Among children <18 years of age, the most commonly reported symptom profiles on the date of first positive rRT-PCR were upper respiratory symptoms alone (n = 3 [21%]) or lack of symptoms (n = 3 [21%]). Among adult household contacts, the most commonly reported symptom profiles were as follows: 6 (18%) experienced at least 1 symptom in each category (constitutional, upper respiratory, lower respiratory, neurologic, and gastrointestinal) and 5 (15%) experienced no symptoms at date of first positive rRT-PCR. No person presented with only constitutional or only gastrointestinal symptoms on the date of first positive rRT-PCR (Figure 4).

Combinations of coronavirus disease 2019 symptoms reported by household contacts on the date of first positive severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction test (n = 47). Constitutional: fever, chills, muscle aches, fatigue. Upper respiratory: runny nose, nasal congestion, sore throat. Lower respiratory: cough, discomfort in chest, shortness of breath, wheezing, chest pain. Neurologic: headache, loss of taste, loss of smell. Gastrointestinal: nausea, diarrhea, abdominal pain.

The median duration of illness with any symptom was at least 16 days (interquartile range, 11–21 days; n = 14); 30% of individuals were still symptomatic at study close-out. Among rRT-PCR–positive household contacts, 25% developed symptoms 3 days (95% confidence interval [CI], 2–4 days) after exposure (symptom onset in the presumed household source case), and the estimate increased to 50% at 4 days (95% CI, 3–5 days), and 75% at 6 days (95% CI, 5–9 days) postexposure. In addition, 50% of the household contacts tested positive by rRT-PCR 6 days (95% CI, 5–7 days) after the onset of symptoms in the household contact, increasing to 75% at 8 days (95% CI, 7–11 days).

Figure 5 shows symptoms relative to rRT-PCR results for 5 contacts who were rRT-PCR negative on day 0 and then positive during follow-up, and 6 contacts who had no symptoms at collection date of first positive rRT-PCR. Nearly all (n = 10 [91%]) contacts reported upper respiratory and/or neurologic symptoms, with longer overall duration observed for the upper respiratory symptoms. About a quarter of contacts (n = 3 [27%]) reported gastrointestinal symptoms; no gastrointestinal symptoms were reported in isolation, and all resolved within 72 hours of onset. Younger household contacts reported fewer symptoms overall, and when symptoms did occur, duration of illness tended to be shorter.

![Timeline of symptom onset in household contacts who changed from negative for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (by real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction [PCR]) on day 0 to positive during follow-up (individuals A–E; n = 5) and contacts who were asymptomatic at collection date of first positive specimen (individuals F–K; n = 6) but developed symptoms later. aFirst household exposure (defined as symptom onset in the household source case) to enrollment (day 0).](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/cid/73/7/10.1093_cid_ciaa1072/1/m_ciaa1072f0005.jpeg?Expires=1749818061&Signature=fu7e6JzNfrWUdnIJz51wDkfox4Tz4pXFrmzoaLspDTKEpXBAbbSmD04quv03KSBH~tuwIOlPnuQpFfxH~BCQwh8RBgPqBprkhX7DnQ7jVC-wEqI6TOkrPig4JbLyVJ-s1hYS9UE4mKBa2AHRUUGTGSRyTTh9QiiN~ZPM-NvkruE7Hqxuy1nJOHQhweA~rBt4XgU29UlSminPiPh8bctenbeSHYK5vKFGOG~OLktu2LewFFifliJPUC~2FEbXiPflwmHLcc3-hAwUvmgH8aYCHXjQQGDyKQp~kf3OS2umYk-9XvlmqLec8Jx6ZPWMIc3OAg1S5mXVsn8nyCXnZPJoOA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Timeline of symptom onset in household contacts who changed from negative for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (by real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction [PCR]) on day 0 to positive during follow-up (individuals A–E; n = 5) and contacts who were asymptomatic at collection date of first positive specimen (individuals F–K; n = 6) but developed symptoms later. aFirst household exposure (defined as symptom onset in the household source case) to enrollment (day 0).

Of the 8 (17%) individuals who did not have symptoms at the date of first positive rRT-PCR, 2 (4%) had prior symptoms that resolved by collection date of first positive rRT-PCR; the remaining 6 (13%) individuals developed symptoms during the follow-up period or were considered “presymptomatic” (5 within 48 hours of positive rRT-PCR collection, and 1 within 5 days).

DISCUSSION

The symptom profiles and demographic characteristics of our cohort of SARS-CoV-2 rRT-PCR–positive household contacts differ from those described in inpatient populations [3–5, 12]. Our findings indicate that mild upper respiratory and neurologic manifestations may be more common and findings such as fever and cough may be less common among the nonhospitalized population than previously appreciated. Additionally, we observed no continually asymptomatic individuals in our study; 6 (13%) individuals who had no symptoms at the collection date of first positive rRT-PCR all went on to develop symptoms during follow-up. This has important implications for diagnosis and community mitigation strategies such as clinical case definitions, symptom screening, temperature screening, testing, and return to school policies. Our findings also emphasize the importance of widespread preventive measures since individuals with mild symptoms are difficult to identify without testing but may still be a source for spread of infection.

We compared the demographic characteristics and symptom profiles of our cohort of household contacts to those of inpatients described by the COVID-19–Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network (COVID-NET) [12]. We found that our population was younger (28% vs 75% aged ≥55 years), less likely to be male (38% vs 54%), and had fewer individuals with 1 or more underlying health conditions (51% vs 89%) [12]. We compared our cohort’s symptoms on date of first positive rRT-PCR to the symptoms on day of admission described in COVID-NET; we found that our cohort was less likely to report cough (43% vs 86%), fever or chills (19% and 6% vs 85%), or difficulty breathing/shortness of breath (11% vs 80%). COVID-NET and additional studies have also described gastrointestinal symptoms in a significant proportion of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 [12–15] with COVID-NET reporting 27% and 24% of inpatients having diarrhea and nausea/vomiting, respectively [12]. In contrast only 13% of our cohort reported diarrhea, and 9% nausea/vomiting at collection date of first positive rRT-PCR; 36% and 19% reported having ever had diarrhea or nausea/vomiting, respectively.

The symptoms that were most commonly reported by our cohort at the date of first positive rRT-PCR were upper respiratory (primarily nasal congestion and runny nose), and neurologic (primarily headache). Only 19% of our cohort reported fever (subjective or objective) on the collection date of first positive rRT-PCR and 53% reported ever having had fever during the 14-day observation period. When comparing symptom profiles by age group, we found that children aged <18 years were more likely to be asymptomatic compared to persons 18 years or older, and symptomatic children were most likely to report upper respiratory symptoms. Several studies have noted that the inpatient COVID-19 population tends to be predominantly male and that males have a higher morbidity and mortality when hospitalized for COVID-19 [12, 16]. However, we did not observe any statistically significant differences in reported symptoms stratified by sex.

We also identified a significant proportion of individuals (13%) who were asymptomatic on the collection date of the first positive specimen. This proportion of asymptomatic individuals is similar to that found in other younger, more healthy populations such as Navy service members where 20% of COVID-19 cases were asymptomatic [17]. However, it is important to note that all of the asymptomatic individuals in our population went on to develop symptoms over the 14-day follow-up period. This is consistent with another longitudinal study that found only 2% of individuals who were asymptomatic at diagnosis remained asymptomatic throughout a 14-day observational period [18]. In contrast, a review of 16 COVID-19 observational studies found that 40%–50% of individuals with COVID-19 were asymptomatic (although only 5 of the 16 cohorts provided longitudinal data); the 5 studies with longitudinal data found that very few asymptomatic individuals (~10%–15%) went on to develop symptoms [19]. Notably, our prospective design included asking each contact about 18 different symptoms daily for 14 days. Other observational or retrospective studies likely identified symptoms differently, possibly less granular and/or sensitive. It is possible that individuals classified as asymptomatic in other studies may be classified as symptomatic using the methodology in our study. Understanding the spectrum of the natural history of COVID-19 is important, but even so, there may continue to be challenges identifying COVID-19 cases early due to nonspecific or mild symptoms.

The study findings presented here must be interpreted in light of several potential limitations. First, symptom data were self-reported and may be subject to recall bias, when symptom onset preceded the day 0 visit. Also, symptoms are subjective by definition and hence individuals may experience and report symptoms differently. Second, by the time we reached the households, 89% of rRT-PCR–positive household contacts were already positive (ie, positive by rRT-PCR on day 0). Prior symptom data were captured but not recorded daily. To allow for a granular description of day-by-day symptom evolution, we limited our sample to household contacts who were negative on enrollment (day 0) but tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 during the 2-week longitudinal follow-up period. This ensured that an accurate natural history was captured but reduced the sample size described. Third, there were 2 household contacts where symptoms had resolved by collection date of first positive rRT-PCR, likely because we missed the date of first detectable virus by rRT-PCR. Fourth, household contacts were selected by convenience sample and therefore are not representative of all US households.

We describe a cohort of household contacts with SARS-CoV-2 infection who have milder symptoms (upper respiratory and neurologic), fewer systemic signs of infection (fever), and who did not require hospitalization. These individuals would not be easily identified as having COVID-19 through common symptom criteria (fever, cough, shortness of breath) or temperature screening. Our findings can inform quarantine strategies for household contacts of individuals with SARS-CoV-2 infection and emphasize the importance of widespread use of community mitigation measures (social distancing, face coverings, respiratory hygiene) to stop the spread of disease by those with milder symptoms who go unidentified as having COVID-19. This is particularly important in younger populations where we identified higher proportions of presymptomatic individuals and individuals with milder symptoms. Because symptom and temperature screening alone will be inadequate to identify all SARS-CoV-2–infected persons, it is important that guidance concerning younger populations, such as return to school policies, emphasize widespread infection prevention and control measures (virtual learning, social distancing, face coverings, hand hygiene with either soap and water or a hand sanitizer, covering coughs and sneezing with a tissue, ensuring availability of adequate supplies of soap and hand sanitizers containing at least 60% alcohol, environmental cleaning and disinfection, and posting COVID-19 infographics in highly visible locations) [20–24]. Our findings of mild symptoms and a short duration from exposure to symptom onset (median of 4 days) can inform quarantine strategies for household contacts of individuals with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors thank the following individuals: Salt Lake County (Utah) Health Department: Dagmar Vitek, Ilene Risk, Ha Khong, LeeCherie Booth, Jeff Sanchez, Madison Clawson, Tara Scribellito; Davis County (Utah) Health Department: Sarah Hall, Sarah Willardson; Summit County Health (Utah) Department: Carolyn Rose; North Shore (Wisconsin) Health Department: Kala Hardy, Christine Cordova, Kevin Rorabeck, Kathleen Platt; City of Milwaukee (Wisconsin) Health Department: Jeanette Kowalik, Heather Paradis, Julie Katrichis, Catherine Bowman, Nancy Burns, Barbara Coyle, Elizabeth Durkes, Carol Johnsen, Jill LeStarge, Erica Luna-Vargas, Sholonda Morris, Mary Jo Gerlach, Jill Paradowski, Lindsey Page, Bill Rice, Michele Robinson, Virginia Thomas, Keara Jones, Chelsea Watry, Richard Weidensee; Wauwatosa (Wisconsin) Health Department: Laura Conklin, Paige Bernau, Emily Tianen; City of Milwaukee (Wisconsin) Health Department Laboratory SARS-CoV-2 testing team: Jordan Hilleshiem, Beth Pfotenhauer, Manjeet Khubbar, Jennifer Lentz, Zorangel Amezquita-Montes, Kristin Schieble, Noah Leigh, Joshua Weiner, Tenysha Guzman, Kathy Windham, Julie Plevak; Utah Department of Health COVID-19 response team: Robyn Atkinson-Dunn; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 Response Team: John Watson, Katharine Battey; Wisconsin Department of Health Services COVID-19 response team; and Utah Public Health Laboratory SARS-CoV-2 testing team.

Financial support. Study funded through general funding for CDC SARS-CoV-2 response. No funding through grants.

Potential conflicts of interest. The authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

References

Author notes

A. R. Y. and L. M. D. contributed equally to this work.

- polymerase chain reaction

- coronavirus

- fever

- child

- infectious disease contact tracing

- prospective studies

- signs and symptoms, respiratory

- wisconsin

- infections

- nasopharynx

- public health medicine

- severe acute respiratory syndrome

- community

- transmission of virus

- diaries

- sars-cov-2

- covid-19

- asymptomatic infections