-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

S De Meulder, T Allaeys, M Vereecken, E Bottieau, M Behaeghe, I Surmont, F Rogge, S Vandelanotte, J T Van Praet, Persisting Eyelid Swelling in a Traveler Returning From Peru, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 65, Issue 6, 15 September 2017, Pages 1048–1049, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cix415

Close - Share Icon Share

(See page 1047 for the Photo Quiz.)

DIAGNOSIS: SUBCUTANEOUS SPARGANOSIS

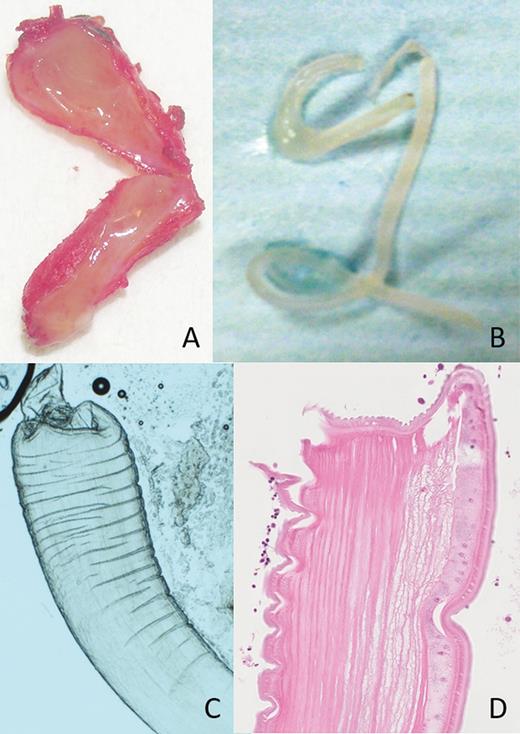

Surgical excision of the cyst was performed, which contained 1 larva of about 3 cm (Figure 1). Care was taken to retrieve the cyst “en bloc” without damaging the outer wall. Macroscopically, it was white, wrinkled, and ribbonlike (Figure 1A and B). Microscopically, it showed to be a cestode larva (Figure 1C and D), characteristic of the larval stage of the Spirometra species.

Sparganum removed from the lower eyelid. Panel A and B show the macroscopic features, whereas C and D (with H&E stain) are microscopic images.

Human sparganosis is a food-borne zoonosis caused by the larvae (spargana) of diphyllobothroid tapeworms belonging to the genus Spirometra [1–3]. Infection in humans most commonly occurs by drinking/swallowing water with procercoid-contaminated copepods (the first intermediate crustacean host) or by consuming undercooked plerocercoid-contaminated second intermediate hosts such as fish, reptiles, or amphibians. Some local practices of placing poultices of frog or snake flesh on the eyes or on open wounds can also transmit infection. Sparganosis is most prevalent in East and Southeast Asia, with only sporadic cases reported from South America, Africa, and Europe [4], and very few in travelers. When humans are infected, the larvae tend to migrate to subcutaneous tissues, although their final location can be anywhere in the body (e.g., brain, eye, abdominal cavity, etc.). Depending on their location, they can cause moderate discomfort or more severe complications such as hemiparesis and seizures. Due to the nonspecific features of sparganosis, the disease is easily misdiagnosed. A definitive diagnosis is made by surgical removal of the worm from the infected tissue. This is also the treatment of choice. When surgery is impossible, praziquantel is the drug of choice, based on expert opinion.

In retrospect, our patient reported eating raw fish and drinking possibly contaminated water on one occasion. This case illustrates that sparganosis is a potential travel-related health hazard and highlights the need of public awareness about the disease, especially with the growing consumption of raw meat of freshwater frogs and snakes [1]. Interestingly, this patient was infected during only a 3-week travel in an area where no cases have been reported.

Notes

Acknowledgement. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of Figure 1.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References