-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Yukihiro Yoshimura, Kazuhiko Nakaharai, Natsuo Tachikawa, A 23-Year-Old Man With Acute Abdominal Pain After Brain Surgery, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 65, Issue 4, 15 August 2017, Page 700, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cix282

Close - Share Icon Share

(See page 699 for the Photo Quiz)

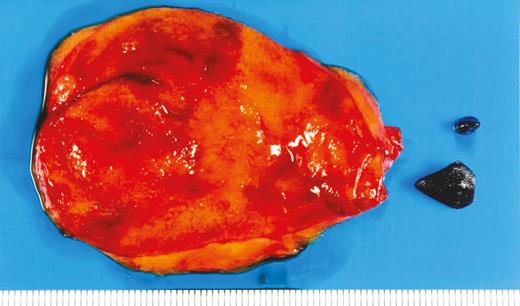

Diagnosis: Ceftriaxone-associated pseudocholelithiasis. The clinical course of an acute episode of gallstone formation with the prolonged high-dose (4 g/day) ceftriaxone therapy suggests that the stones were secondary to the antibiotic exposure. Black gallstones can be formed in hemolytic disorders or cirrhosis [1], which were absent in the patient. However, when he presented with acute abdominal pain, ceftriaxone-associated pseudocholelithiasis was suspected, and the antibiotics were changed. He was discharged 2 weeks after the attack and presented with no subsequent abdominal pain. The gallbladder stones were identified 3 months after discharge. Therefore, laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed, and the black stones were removed (Figure 1 Answer).

Ceftriaxone is one of the most common and well-tolerated antibiotics used in hospitals [2]. However, adverse events such as liver injury may increase in high-dose treatment [3]. Ceftriaxone, which is excreted and concentrated in gallbladder bile, can form a precipitate, ceftriaxone–calcium salt, which may cause biliary sludge formation [4]. Additionally, ceftriaxone-induced biliary sludge is likely to be formed in patients who receive high-dose treatment (≥2 g) [5]. Although ceftriaxone-associated pseudocholelithiasis has been reported more frequently in children than in adults [6, 7], their incidence is similar (18% vs 21%). In a prospective study of 20 adults who were administered ceftriaxone, 5 developed pseudocholelithiasis within 4–17 days of administration, and all stones disappeared 10–26 days after ceftriaxone discontinuation [8]. In this case, the gallbladder stone did not disappear 3 months after ceftriaxone discontinuation, and surgery was needed. Physicians should be aware that gallbladder stones associated with ceftriaxone administration can occur and that they may disappear with drug discontinuation.

Note

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

Author notes

Correspondence: Y. Yoshimura, Yokohama Municipal Citizen’s Hospital. 56 Okazawa-cho, Hodogaya-ku, Yokohama city, Japan ([email protected]).