-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Ola Grimsholm, CD27 on human memory B cells–more than just a surface marker, Clinical and Experimental Immunology, Volume 213, Issue 2, August 2023, Pages 164–172, https://doi.org/10.1093/cei/uxac114

Close - Share Icon Share

Summary

Immunological memory protects the human body from re-infection with an earlier recognized pathogen. This memory comprises the durable serum antibody titres provided by long-lived plasma cells and the memory T and B cells with help from other cells. Memory B cells are the main precursor cells for new plasma cells during a secondary infection. Their formation starts very early in life, and they continue to form and undergo refinements throughout our lifetime. While the heterogeneity of the human memory B-cell pool is still poorly understood, specific cellular surface markers define most of the cell subpopulations. CD27 is one of the most commonly used markers to define human memory B cells. In addition, there are molecular markers, such as somatic mutations in the immunoglobulin heavy and light chains and isotype switching to, for example, IgG. Although not every memory B cell undergoes somatic hypermutation or isotype switching, most of them express these molecular traits in adulthood. In this review, I will focus on the most recent knowledge regarding CD27+ human memory B cells in health and disease, and describe how Ig sequencing can be used as a tool to decipher the evolutionary pathways of these cells.

Introduction

There are several important molecular markers of B-cell memory. These include a class-switched B-cell receptor (BCR), which is induced by the process of class-switch recombination (CSR), and somatic mutations in the immunoglobulin (Ig) variable genes, which emerge during the process of somatic hypermutation (SHM). In adults, the majority of long-lived memory B cells (MBCs) carry somatic mutations in their Ig variable genes and/or have undergone CSR. In the past decade, much has been discovered regarding the heterogeneity of MBCs using mouse models in which CD73, CD80, and PD-L2 have been used extensively as markers to define B-cell subpopulations [1–3]. However, these markers cannot be used to define MBCs in humans, given that several surface markers show different expression patterns in the two species [4]. For instance, in humans most of the highly selected MBCs express on their cell surfaces the classical memory marker CD27 [5, 6], which is a member of the TNF superfamily, but only a minor MBC population in mice expresses CD27 [7].

The concept of immunity has been known since Jenner and Panum made their field observations of smallpox and measles, respectively [8, 9]. They showed that changes to the immune system, generated by the response to a pathogen, reinforce the ability of the organism to face a re-infection thus preventing the disease. Pre-existing antibodies that are secreted by long-lived plasma cells (PCs) play an important role in immune protection. Vaccines protect from infection because they induce immunological memory. Vaccines have paved the way towards the eradication of several serious illnesses in the last decades, such as smallpox and polio, with the latter still presenting in minor localized outbreaks [10]. It is clear that many vaccines induce stable antibody serum titres, showing low turnover, although how these titres correlate with different MBC subsets is still not fully elucidated [11].

Immunological memory is the ability to respond in a different manner upon re-infection as compared to the primary response, leading usually to prevention of the illness or to a less-severe disease. Protection is mainly mediated by antibodies in collaboration with memory T and B cells and the help of other cells [12, 13]. There are three main hallmarks of immunological memory: specificity, longevity, and efficiency. Specificity is the ability of one antibody to bind to a certain member of, for example, a protein family but not to another related protein. Longevity is the durability of immunity induced by a previous infection or vaccination. The efficiency of the immune response attributable to immunological memory ensures rapid clearance of the infectious agent upon re-infection. There are also negative aspects of immunological memory. For example, its de-regulation is implicated in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases. In autoimmune diseases, impairment of tolerance checkpoints for self-antigens leading to tolerance breakage may be the driving force, which could secondarily give rise to autoreactive MBCs. In this review, I will focus on human MBCs that express the fundamental marker CD27 in both health and disease, and outline what we know about the function of this molecule in MBCs. I will also highlight the importance of Ig sequencing for understanding the CD27+ MBC compartment and finally, I will briefly discuss newly described markers for MBCs in humans which may be valuable for explaining the heterogeneity of the MBC compartment, particularly for tissue-resident MBCs.

The formation of human memory B cells in germinal centres

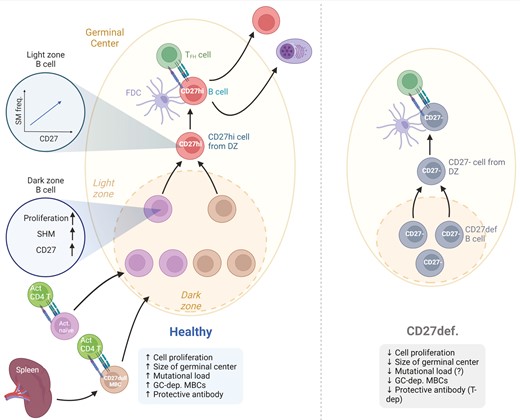

Memory B cells are generated during adaptive immune responses and the majority of them inside the GC reaction in response to TD antigens [14]. The activated B cell moves toward the border of T and B cell zone in the secondary lymphoid organ where it will interact with the cognate T helper cell. A fraction of the activated B cells will then subsequently seed the GC reaction. Upon the formation of the GC reaction, B cells will continue to proliferate and also acquire somatic mutations into their Ig V region genes inside the dark zone [15] (Fig. 1). Many of the mutations will be erroneous and these cells will undergo apoptosis but those GC B cells expressing a BCR with a relevant affinity to the antigen will become selected by the T follicular helper cells in the light zone. For many years it was assumed that CSR occurred in the GC B cells when in the light zone, but recent data have challenged this dogma. Roco et al. suggested that it is during the initial phase prior to the formation of the GC that activated B cells undergo CSR [18]. However, this still remains controversial and definitive proof in humans is still needed.

![CD27 in GC-dependent memory B-cell formation. Activated naïve B cells and previously formed CD27−/dull MBCs receive cognate T-cell help and enter into the GC reaction. There, they undergo proliferation, acquire somatic mutations in their Ig variable genes and up-regulate CD27. In a recent paper by James and colleagues, it was shown that the higher the level of CD27 expression in GC B cells the higher the frequency of somatic mutations [16]. In a functional GC, CD27bright MBCs will be formed and will exit the GC reaction together with long-lived PCs. In CD27 immunodeficiency, proliferation is presumably affected because the GC is smaller [17]. The response to T cell-dependent vaccinations is decreased in many patients, although there is lack of data on somatic mutations in the CD27− MBCs that are formed. PC formation during T cell-dependent stimulation is also reduced. Created with Biorender.com.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/cei/213/2/10.1093_cei_uxac114/2/m_uxac114_fig1.jpeg?Expires=1749585128&Signature=KutSjripYGCycVRA~lHRdKhjb9ksTqZy97faZH-oJbZLAkw2zZ951SPxcHNpdonXBVYovqI49EQweknYtz9Iaj-71ZCBW9FfVnIZmqdPKDj4-D47iPbCobLhgfWpf674mq4vUV9pviTnkDkj-luHPsokcfTyYBRkIX6~Gyvwtrqff2eEiYMzrXzPwPk224Bmib6HNkp3yiYyoao-H5ERygFp8eAwjlRYn8sALIyGoCysuWdxD0WeSokHxx2H-~IxCpVkqsHw~X6cKKxUCduK61Z3ZIVGjQ5LatI5r6s1Pf9BeH7jU-6V-eWHdOo31-nX1UblBtjJ5AcnJX33pLsx5Q__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

CD27 in GC-dependent memory B-cell formation. Activated naïve B cells and previously formed CD27−/dull MBCs receive cognate T-cell help and enter into the GC reaction. There, they undergo proliferation, acquire somatic mutations in their Ig variable genes and up-regulate CD27. In a recent paper by James and colleagues, it was shown that the higher the level of CD27 expression in GC B cells the higher the frequency of somatic mutations [16]. In a functional GC, CD27bright MBCs will be formed and will exit the GC reaction together with long-lived PCs. In CD27 immunodeficiency, proliferation is presumably affected because the GC is smaller [17]. The response to T cell-dependent vaccinations is decreased in many patients, although there is lack of data on somatic mutations in the CD27− MBCs that are formed. PC formation during T cell-dependent stimulation is also reduced. Created with Biorender.com.

A proportion of the selected GC B cells in the light zone will re-enter the dark zone for more rounds of somatic mutations whereas others will differentiate into MBCs or long-lived PCs and exit the GC [19]. In mice, it has been demonstrated that B-cell memory can be formed independently of the GC [20] but whether all human long-lived CD27+ MBCs are formed inside the GC or not remains to be shown.

The function and expression of CD27 and its ligand CD70

The expression patterns of CD27 and CD70

CD27 is expressed by resting cells such as CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and NK cells [21]. CD27 expression is down-regulated on effector T cells but it is still expressed on memory CD4+ T cells [22]. Over two decades ago, a subpopulation of human peripheral blood (PB) B cells was shown to express CD27 [23] and to carry somatically mutated BCRs, i.e. appearing as MBCs [24]. The compartment of PB CD27+ MBCs is generally divided into four subsets: switched, IgM+IgD+ (also called marginal-zone like), IgMonly, and a minor population of IgDonly [24, 25]. These subsets have been investigated extensively [26–30] and the central characteristics of each subset will be reviewed below. In addition to MBCs, GC B cells and PCs in human tonsils have been demonstrated to express CD27 as well, with PCs exhibiting the highest CD27 expression levels of all B-cell subsets [7, 31]. It has recently been demonstrated at the single-cell level in human tonsils that the expression of CD27 is higher in GC B cells that have an increased number of somatic mutations [16]. This concords with earlier results indicating increased numbers of CD27+ B cells in the GC light zones of human lymph nodes [32]. It has also been shown that the expression pattern of CD27 differs between organs, whereby, for example, the switched MBCs in the spleen express lower levels than those in the peripheral blood [4]. The reason for these differences is not well understood.

The only known ligand for CD27 is CD70, which shows a cellular expression pattern that is much more restricted than that of CD27. CD70 is expressed during the activation of dendritic cells, as well as by T cells [33]. Its expression on B cells is very limited and it is almost exclusively found on cells that express CD27 [32–34].

The functions of CD27 and CD70

CD27, which is a member of the TNF receptor superfamily (TNFRSF), is a Type 1 transmembrane glycoprotein with three cysteine-rich domains [35]. It is normally found on the cell surface as a disulphide-linked homodimer, although it can also be detected as a monomer in the serum under certain inflammatory conditions, such as autoimmune diseases [21]. In CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses the CD27–CD70 interaction can provide survival signals as well as influencing the CD4+ T cell responses qualitatively [36, 37]. The interactions that occur between CD27 and CD70 during B-cell activation have also been examined and it has been shown that CD27 ligation in vitro can enhance Ig production, for example, cells transfected with CD70 can stimulate B cells to increase their IgG production [38, 39]. Moreover, a proportion of CD27+ B cells expresses CD70 upon stimulation, and those B cells that express both CD27 and CD70 secrete Ig in greater amounts [33]. Thus, the interaction between CD27 and CD70 on T and B cells might influence the B cell response in the GC in different ways such as priming and proliferation [40]. In line with this, a recent report has looked extensively at the interaction between CD27 and CD70 and has proposed that this interaction is crucial as a co-stimulatory signal for both B-cell and T-cell activation [41]. Thus, CD27 is not only a commonly used marker for MBCs, but it is presumably essential for the activation of B cells and the formation of MBCs. This idea is further supported by the fact that both CD27 and CD70 deficiencies lead to severe consequences for the MBC compartment, as will be discussed below [42]. Additional investigations are needed to understand the importance of CD27 for long-term immunological memory.

CD27 deficiency

There is a rare immunodeficiency caused by mutations in the CD27 gene [17]. Patients who carry this mutation often suffer from EBV-driven lymphoproliferation, which in many cases develops into lymphoma [43]. Our knowledge as to how this mutation affects the B-cell compartment is currently limited, although we do know that the numbers of CD27+ MBCs are reduced significantly in these patients [42]. An earlier study demonstrated that two patients with CD27 deficiency had smaller GCs and did not respond to T cell-dependent vaccination (Fig. 1) [17]. The PC compartment is sometimes also affected, as the serum levels of all the isotypes (IgG, IgA, and IgM) are drastically reduced in at least some of the patients, most probably reflecting the type of mutation present [17]. The function of CD8+ T cells is also severely impaired in these patients, although hematopoietic stem cell transplantation can restore this defect and, thereby, reduce the risk of lymphoma [42]. However, we lack sufficient information on the effect of CD27 deficiency on the function of the GC. Thus, the efficiency of SHM or CSR has not been investigated thoroughly, although an initial report on two patients indicated a normal frequency of SHM [17]. It would be of great interest to pursue an in-depth study on Ig heavy chain mutations and clonal relationships in CD27 deficiency, so as to deepen our understanding of the consequences of CD27 deficiency for the process of SHM and the function of CD27 for GC-dependent MBC formation. If feasible, needle biopsies of lymph nodes in parallel with PB samples would be very informative, since these patients still make smaller GCs [17]. This might also reveal important information about GC-independent MBCs in humans and their relationships to GC-dependent MBCs. The reasoning behind this is that CD27− MBCs are still present but their relationships with GC-dependent CD27+ MBCs are still unclear. In addition, it could be deciphered whether those CD27− MBCs in CD27 deficiency are the same as double-negative MBCs appearing in healthy donors.

CD27+ memory B cells—different subsets

Ever since the discovery of CD27 as a cell surface marker of human MBCs, much effort has been expended towards understanding the heterogeneity of the CD27+ MBC subsets [44]. Many groups have also shown that CD27+ MBCs are established early in life [30, 45, 46], and we have recently added to this by defining these as CD27dull MBCs in the PB [47]. In the seminal paper by Klein et al. it was clearly demonstrated that both CD27+IgM+IgD+ and CD27+IgMonly are somatically mutated in their Ig V genes (and to a similar extent) and that the small fraction of CD27+IgDonly is highly mutated [5]. The heterogeneity of CD27+ MBCs could also possibly be translated into layers of B-cell memory where CD27+IgM+IgD+ B cells would represent a more primitive layer that can become adapted in the GC whereas CD27+ switched MBCs makes up the more adapted and evolved layer. This will be discussed below.

CD27+ switched MBCs

Switched CD27+ MBCs have traditionally been regarded as the main post-GC MBCs, even though IgM+ MBC subsets also take part in GC reactions [28, 30, 45]. In response to Toll-like receptor (TLR) 9 stimulation, CD27+ switched MBCs differentiate into plasmablasts [48], which is also evidenced at the transcriptional level by the up-regulation of Prdm1 [49]. Thus, switched CD27+ MBCs are poised to differentiate into plasmablasts upon re-stimulation, and are the main precursors that differentiate into high-affinity antibody-producing cells upon re-stimulation [48–51]. Hence, this subset represents a layer of memory with already highly selected MBCs that are ready to respond quickly to re-infection by differentiating into antibody-secreting cells. In a recent elegant study, Chappert et al., demonstrated that long-lived MBCs specific to the smallpox protein B5 are enriched within the CD27+IgG+ subset in the spleen and that these also expressed both CD21hi and CD73 [52].

CD27+IgM+IgD+ (MZ-like) B cells and splenic marginal zone B cells

There is an ongoing debate as to whether CD27+IgM+IgD+ B cells which are also called marginal zone (MZ)-like B cells, truly represent a MBC population or instead develop along a different pathway [29, 30, 44, 45, 53]. There is evidence that CD27+IgM+IgD+ B cells can home to the gut where they can acquire somatic mutations in GCs [27, 29, 53–55]. Furthermore, the numbers of CD27+IgM+IgD+ B cells are greatly reduced in asplenic patients [26, 56], pointing towards a splenic reservoir for these cells. With advancing age, although CD27+IgM+IgD+ B cells can develop without GCs [56], these cells progressively acquire somatic mutations inside the GC [45]. Thus, although CD27+IgM+IgD+ B cells seem to develop along a different developmental pathway, with age this population contains more and more GC-experienced cells. It could thus be suggested that this subset represents a layer of memory that has the potential to be further adapted through new immune responses.

In humans, the splenic marginal zone (sMZ) in adults is composed of B cells that have somatic mutations in their Ig V genes, CD27 expression, and high proliferative capacity [6, 30, 57, 58]. Thus, they are very similar to PB CD27+IgM+IgD+ B cells, and it is debated as to whether these cells correspond to GC-derived B cells or are from an independent pathway. Accumulating evidence suggests that the composition of the sMZ differs between children and adults, such that in young children it contains B cells from a potentially distinct pathway [46], whereas in adults it is dominated by post-GC CD27+IgM+IgD+ and IgG+ B cells [54, 59]. Along this line, a recent report has shown that a CD27- subset with molecular features reminiscent of sMZ B cells is established in the sMZ of infants, although whether or not these are clonally related to later CD27+ sMZ subsets is currently unknown [46]. The same group showed earlier that the spleen works as an archive for MBCs throughout life [53]. In brief, the authors demonstrated that a PB CD27+ MBC clone always had a corresponding member in the spleen, and that this was the case for all donors older than four years. They also reinforced the findings that sMZ B cells in young children acquire somatic mutations in the GC, as previously demonstrated [45, 59]. It has also become clear that there are NOTCH2-dependent CD27− cells that express CD45RB and that these act as precursors to the cells residing in the sMZ [55, 60, 61]. Recently, Siu et al. have demonstrated that there are two subsets of B cells in the MZ and that they express different levels of CD27 [29]. This was also reflected in the number of somatic mutations in the two subsets, with the subset expressing lower levels of CD27 having fewer somatic mutations [29].

The CD27+IgMonly MBCs

CD27+IgMonly MBCs have been shown to be clonally related mainly to switched CD27+ MBCs [54]. Furthermore, this subset has also been correlated with the presence of GC reactions in activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID)-deficient patients [30]. Thus, this subset is most likely composed of mainly GC emigrants [54]. However, as pointed out by Weill and collaborators, the expression pattern of IgD and CD27 on the IgMonly subset is heterogeneous and, therefore, overlaps with the MZ and double-negative subsets [54]. In the gut, it has been suggested that CD27+IgMonly MBCs can be related to both CD27+IgM+IgD+ B cells and CD27+ IgA-switched MBCs (but not in the same clone), indicating heterogeneity within the CD27+IgMonly subset [55].

The CD27+IgDonly subset

CD27+IgDonly MBCs have been described in detail in an excellent review by the group of Cerutti [62]. These MBCs are very rare in the PB of humans, representing 0.1–0.5% of B cells, but are detected more frequently in the tonsils, especially among PCs. The class switching to IgD from IgM is particular since the Cδ gene lacks a canonical S region. Instead, it has a cryptic short intronic region located between Cμ and Cδ, which acts as an acceptor site for the donor Sμ region and thereby mediating a non-homologous IgM to IgD switching [25, 63, 64]. These cells form in the tonsils and from there re-circulate to mucosal sites such as the nasal cavities, lacrimal glands, and salivary glands [63, 65]. The somatic mutation rate in CD27+IgD+ MBCs is high [5], and they have an extraordinarily high frequency of lambda-expressing cells, as well as biased VH expression [25, 63].

MBC markers other than CD27

Over the last decade, it has become increasingly clear that a non-negligible proportion of human MBCs do not express CD27 on their surface. Recent multiomics approaches have also revealed that the PB MBC compartment contains cells expressing other markers than CD27 such as CD45RB, CD11c, CD39, CD73, and CD95 [66]. They suggested that there are up to 12 different MBC subsets across four lymphoid tissues. One of the most examined subsets is the CD21−/low MBCs [67], which are enriched in subjects with autoimmune diseases or chronic infections [68]. This population contains both CD27+ and CD27- cells. As this topic has been extensively reviewed recently [68], only a few points will be highlighted here. A recent thorough study of the phenotypes of human MBCs in different tissues (blood, spleen, tonsils, and gut) has shown that the CD27− MBC subsets vary significantly between the lymphoid tissues (peripheral blood, spleen, tonsils, and gut) of healthy donors [69]. It was, however, early on shown that CD27− switched MBCs could be found in the same lineage trees as CD27+ switched MBCs [70], albeit with fewer mutations, pointing towards a less ‘mature’ MBC that either had a GC-independent origin or exited the GC-reaction early. Moreover, we do not know whether CD27− MBCs have previously expressed CD27 on their cell surfaces, even though this remains a possibility since they are clonally related. There is also evidence that the CD27- MBC compartment can be divided into distinct T-dependent and T-independent pathways [71].

Tissue-resident MBCs appear to comprise both CD27− and CD27+ arms [68]. CD45RB and CD69 have recently been described as useful markers for identifying tissue-resident MBCs [69]. Interestingly, in the lungs, a large proportion of influenza-specific CD27+ MBCs express CD69, CXCR3, and CCR6, and are suggested to be resident within this tissue [72, 73]. Furthermore, transcriptional profiling has indicated that these lung-resident MBCs are indeed different from those in lung-draining lymph nodes or PB, suggesting that these lung-resident CD27+ MBCs are different from circulating CD27+ MBCs [73]. Moreover, studies on mice support the idea of these tissue-resident CD27+ MBCs persisting for a longer period of time in the lung [74].

Tracking CD27+ memory B cells using VDJ deep sequencing

A powerful tool for examining the evolution and relationships between different subsets of human MBCs is Ig sequencing with unique molecular identifiers (UMIs). During the past decade, many groups have contributed substantially to our understanding of CD27+ MBCs, using Ig sequencing to show, for example, clonal relationships between subsets and different organs [27, 47, 53–55, 75]. The frequency of clonally related sequences does vary between different studies and tissues where for example Bagnara et al. found that, on average, 16% of the clones were shared with another subset or tissue, but the sharing between CD27+IgM+IgD+ MZ-like B cells and switched CD27+ MBCs was rather limited [54]. Comparing CD27+IgM+IgD+ B cells with CD27+IgMonly MBCs in PB Zhao et al. observed a clonal sharing spanning from 5% to 13% whereas they did only see very limited sharing between gut-associated lymphoid tissue MZ B cells and class switched MBCs [55]. We have found that on average 8.5% of the top 1000 clones were shared between CD27dull and CD27bright MBCs [47]. The cellular composition of CD27dull and CD27bright MBCs where the latter contains more switched CD27+ MBCs and CD27+IgMonly MBCs could be one explanation to the rather low sharing. Thus, clonal relationships between CD27+ MBCs have been demonstrated using Ig sequencing, e.g. between the spleen and PB and between the gut and PB/spleen [27, 53–55]. Recently, in two different Ig sequencing studies it was revealed that the longitudinal composition of PB MBCs is stable and also shows relationships to circulating plasmablasts [76, 77].

A good overview of the different parameters that are examined by adaptive immune receptor repertoire (AIRR) sequencing has been summarized by the AIRR community recently [78]. AIRR sequencing using UMIs alone cannot compensate for clonal expansion, so the risk of detecting false clonal expansions has to be tackled. Furthermore, it should be pointed out that gDNA is more suitable when investigating clonal expansion [78, 79]. To deal with false clonal expansions technical and biological replicates are essential to include [80]. However, when we have cells that produce a large quantity of Ig, e.g. plasmablasts, we cannot tell whether the difference is due to a difference in expression level (i.e. how much Ig a given cell has) or a difference in the number of cells. Thus, the experimental design is crucial to be able to analyse AIRR sequencing data, and this has been extensively reviewed elsewhere [78, 79].

CD27+ MBCs in autoimmune diseases

Our understanding of B-cell memory for self-antigens is still limited owing to the nature of autoimmunity, i.e. that the antigen is in many cases unknown. So far, information on the specific characteristics of Ig heavy chain sequences that can describe binding to autoantigens is very limited. There are a few exceptions to this, such as basic amino acids and their presence in dsDNA-specific autoantibodies [81]. However, the GC reaction works sub-optimally in many autoimmune diseases, which has been e.g. demonstrated in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) where self-reactive germline-encoded VH4-34-expressing antibodies are not counter-selected [82]. Furthermore, in Sjögren’s syndrome, it has been observed that switched CD27+ MBCs are enriched for silent mutations instead of replacement mutations, which suggests that the GC reaction is not working properly [83]. In SLE, it has recently been unveiled that one of the subsets of CD27+IgM+IgD+ B cells is reduced [29] and that this coincides with the increased susceptibility of patients with severe SLE to infections with pneumococcus [84]. In recent years, the focus has been on CD21−/low B cells in autoimmune diseases, while their relationships to CD27+ MBCs remain largely unexplored in these conditions. However, it is well-established that CD27− MBCs are clonally related to CD27+ switched MBCs in healthy individuals as mentioned above. Therefore, it remains a possibility that the same applies to autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and SLE. This is supported by the fact that switched MBCs appear early after rituximab treatment of patients with RA who have a CD27+ subset combined with a CD21−/low and CD95+ activated phenotype [85]. It is likely that these different MBC subsets that appear after rituximab treatment are clonally related to each other, although formal proof is lacking. Further deep sequencing of CD27−/low and CD27+ MBC subsets in different autoimmune diseases is required to shed new light on the selection mechanisms operating in MBCs that are reactive to self-antigens.

CD27dull and CD27bright memory B cells—two sides of the same coin?

We recently conducted a larger study to examine the inter-relationships between CD27dull and CD27bright MBCs in healthy individuals and in different disease groups [47]. We were able to show that CD27dull MBCs occur early in life and remain relatively abundant in adults, while this subset decreases in the elderly, which coincides with weakened vaccine responses in the elderly [86]. The presence of CD27dull MBCs early in life concords with the previous demonstrations by other groups of the occurrence of CD27+ MBCs in infants [30, 45, 46, 53]. Furthermore, it has recently been demonstrated that cells found in the MZ of infants are CD27- [46], and that one of the CD27+IgM+IgD+ B-cell subsets that has been described as MZB-2 exhibit lower expression levels of both CD24 and CD27 [29]. These cells were found in the spleen, gut-associated lymphoid tissue and PB. The numbers of CD27+ MBCs increase rapidly throughout early life until 5 years of age, after which they continue to increase at a somewhat slower pace into adult life [87]. We also showed that the numbers of CD27dull MBCs are decreased in asplenic patients [47], and this concords with previous reports that the numbers of CD27+IgM+IgD+ B cells are reduced in children with asplenia [26, 30].

Instead, the formation of CD27bright MBCs starts at around 2–3 years of age and the process requires a functional GC reaction and T cells (Fig. 1) [47]. This is in accordance with earlier findings that the GC reaction is initiated early in life but is less efficient with fewer somatic mutations [45] and lower expression of CD27 in the resulting CD27+ MBCs. We also observed that CD27+IgMonly MBCs are enriched within the CD27bright subset (unpublished data). The numbers of CD27+ switched MBCs start to increase only after 2 years of age in both the spleen and PB [49, 53]. This explains why CD27bright MBCs develop later than CD27dull MBCs and not until 2–3 years of age as the former population contains more switched cells [47]. This gradual maturation of MBCs, i.e. higher adaptive capacity of less-mature cells, has been shown for different MBC subset relationships, such as IgM vs. IgG [28, 45] and IgM vs. IgA1/A2 [88, 89], as well as within the splenic compartment [53–55]. We suggested that CD27dull MBCs could act as a plastic source for highly selected CD27bright MBCs, but there is no suitable proof for a direct precursor [47]. The results may also be explained by sequential development from the same naïve B cell, as most activated B cells die shortly after proliferation and differentiation, it is not granted that the original ancestor (the precursor) is long-lived. It is also important to point out here that the upregulation of CD27 seen on CD27bright MBCs might not always occur due to competition in the GC. However, in adults, CD27bright MBCs are in most cases extensively mutated and selected MBCs that can rapidly differentiate into antibody-secreting cells upon re-stimulation, e.g. TLR stimulation, thus mimicking to a large extent how CD27+ switched MBCs respond to such stimuli [49]. CD27bright MBCs are largely absent in severe combined immunodeficiency (common gamma chain-deficient) patients even after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, whereby the host B cells are retained but the donor T cells are normal. This indicates that the IL-21R on B cells is crucial for CD27bright MBCs to form inside the GC, which is in line with data obtained from mice where IL21-R is crucial for optimal functioning of the GC reaction [90]. Thus, the absence of CD27bright MBCs could possibly be used as a surrogate marker for a defective GC reaction in various primary immunodeficiencies.

Furthermore, our data, collected in a longitudinal study of pregnant women, indicate that CD27dull MBCs are the ancestor cells to CD27bright MBCs. However, it is well-established that several different processes can influence the MBC subsets observed in the PB. Primarily, tissue homing/egress of CD27+ MBCs can affect the MBC subsets. In this cohort, where it is important to transfer antibodies to the foetus, it could certainly affect the MBC subsets observed in the PB, and it has been demonstrated by several groups that tissue homing/egress affects the CD27+ MBCs in the periphery [27, 53, 55]. It is also possible that the half-life of MBCs affects the change that we observed during pregnancy. Although the half-life of individual MBCs is unexplored in humans, antigen-specific MBCs on a population level persist for decades [52, 91]. The differentiation behaviour of CD27+ MBCs during pregnancy is also unknown, although it is possible that CD27bright MBCs differentiate into plasmablasts during pregnancy. We are presently investigating this in a separate study.

Concluding remarks and perspective

New molecular tools are becoming available to the B-cell research community to facilitate deciphering the regulation and function of human MBCs. It is becoming increasingly clear that the MBC compartment in humans is comprised of a heterogeneous pool of cells with different functions and roles during the B-cell response. Crucial questions remain to be answered. We still do not know exactly which signals drive the formation of MBCs in the GC. Nonetheless, in humans, CD27 is certainly a fundamental molecule, the signalling pathways of which are under-explored. Hopefully, this will be remedied in the near future.

Abbreviations

- AID

activation-induced cytidine deaminase

- AIRR

adaptive immune receptor repertoire

- BCR

B-cell receptor

- CSR

class-switch recombination

- GC

germinal centre

- Ig

immunoglobulin

- MBC

memory B cell

- MZ

marginal zone

- PB

peripheral blood

- PC

plasma cell

- RA

rheumatoid arthritis

- SHM

somatic hypermutation

- SLE

systemic lupus erythematosus

- TD

T-cell dependent

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

- TNFRSF

tumour necrosis receptor superfamily

- UMI

unique molecular identifier

Acknowledgements

I want to thank Dr Rita Carsetti for their critical input and fruitful discussions on the content of this manuscript. I also want to express my gratitude to Drs. Barbara Bohle, Alessandro Camponeschi, and Emiliano Marasco for critically reading the manuscript. Finally, I want to thank Dr Vincent Collins for critical language editing of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Patient consent statement

Not applicable.

Permission to reproduce material from other sources

Not applicable.

Clinical trial registration

Not applicable.