-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Lucie Byrne‐Davis, Stuart N. Cohen, Rebecca R. Turner, Evaluating dermatology education and training, Clinical and Experimental Dermatology, Volume 47, Issue 12, 1 December 2022, Pages 2096–2099, https://doi.org/10.1111/ced.15398

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The purpose of education and training in dermatology ranges from increasing knowledge and skills to improving confidence or enhancing patient outcomes. Specification of the purpose of the education and training is vital so that evaluation can be aligned to purpose, and thus provide evidence on effectiveness. Further, the quality and quality improvement of education and training can be enhanced by a careful specification of how they are expected to achieve their purpose. Multiple theories and methods can be used to evaluate both the process and the outcome of education and training. In this paper, we summarize some of these and focus particularly on the use of behavioural science to evaluate education and training. We illustrate these theories and methods with an example in dermatology.

Introduction

The purpose of educational evaluation is inextricably linked to the purpose of the education itself. When we educate, we expect learners to know more (increased knowledge) and to be able to do more (increased skills). By contrast, the purpose of education is often more than an increase in knowledge and skills. Sometimes, we are also attempting to change variables such as confidence, or motivation to change. Often, we are wanting people to do something differently after education and training. It is important to understand that just because someone knows something or can do something, does not mean that they will behave differently.

Just because I can does not mean I will

Whether an action is undertaken is influenced by three broad constructs, encapsulated by the ‘COM‐B Framework’: capability, opportunity and motivation resulting in a change in behaviour.1 Capability, a familiar construct in education and training, is both psychological and physical. Psychological capability is whether knowledge and cognitive capacity are sufficient. Physical capability relates to the skills required to undertake the new behaviour. Opportunity is both physical opportunity, which covers having the right resources (e.g. time, personnel, equipment), and social opportunity, whether the behaviour is sanctioned (e.g. by peers, supervisors and patients). Motivation is both reflective and automatic. Automatic motivation is whether the behaviour is habitual and happening with little engagement or decision making by the individual, while reflective motivation is actively deciding to do the behaviour, based on weighing up its pros and cons.

If we expect our education and training to lead to a change in practice, we must think broadly about how we evaluate its effectiveness. It is helpful to set out and explore our suppositions about how we think the education will lead to the outcomes.

Common pitfalls of education evaluation

There are various challenges when it comes to evaluating an educational intervention. Commonly, the process involves questions about the mode of delivery, rather than assessing whether there are any changes to determinants of behaviour or measurement of behaviour itself. Although understanding whether learners perceive an intervention as acceptable, useful or enjoyable is superficially useful, effectiveness can be better understood by exploring how it has or has not influenced learners' behaviour. Another common pitfall is to fail to consider theory when developing education; this can lead to problems when attempting to understand why an intervention worked or not. Ways to overcome some common challenges in education evaluation are discussed in this paper. These can be applied to any area of clinical education.

Theory of change

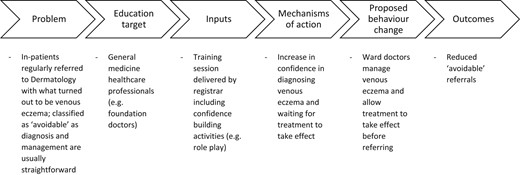

A theory of change sets out what effect you expect from your education or training, how you expect this will happen and any contextual influences. A good theory of change draws on theories to explain potential mechanisms of change. A theory of change can help to assess which aspects of an intervention were effective, by examining several indicators, not just overall outcomes.2 For example, when learning a new skill, modelling of the behaviour is important, according to the Social Learning Theory.3 This mechanism may feature in a theory of change, among other established theoretical mechanisms. Log frames, also known as logical frameworks or logic models, may be used to communicate aspects of a theory of change by providing a graphical illustration of the proposed intervention, the resources required and the predicted outcomes. Theory of change and log frames highlight key aspects of the education and training that are otherwise implicit, and thereby guide what should be evaluated.4 An illustration of this is provided with the example in Fig. 1.

When thinking about education and training as an intervention to effect change, we can use guidelines, theories and methods to guide our evaluations.

The Kirkpatrick model

The Kirkpatrick model proposes four levels of training evaluation. Level 1 is reaction, which is how much the learners liked the learning, in terms of engagement and relevance. Level 2 is the learning level: did the learners' knowledge and skills or other intrapersonal factors, such as confidence, improve? Level 3, behaviour, is whether learners implemented what they learnt into their working lives. Level 4 is about the outcomes and, in the case of most dermatology education and training, is whether the education and training programme led to improved patient outcomes. Recent reviews of healthcare professional education and training programmes have found that evaluation tends to be focused on Levels 1 and 2, for example in the evaluation of online lectures,5 portfolios6 and feedback from workplace‐based assessments.7

Complex intervention evaluation

Complex interventions, which are commonly used within health services, are defined as having several interacting components, targeting various behaviours and having numerous outcomes.8 The UK Medical Research Council has published guidance on how to evaluate complex interventions.9 This guidance states that an important aspect of evaluation design is selecting appropriate outcome measures in line with the research questions. To measure behavioural change, assessment of behaviour at different time points is required to understand whether change is occurring. This can be done both objectively and subjectively.

Objective measures include direct observation before and after the intervention. However, observing multiple individuals over time may not be practical, so asking participants to self‐report their behaviours is an alternative. For example, they could record how many referrals they made before and after the intervention. Additionally, routine data collection (e.g. number of referrals) in the form of an audit can measure behaviour.

Process evaluation

Process evaluations assess how an intervention works or not, by examining factors such as design, implementation, context and mechanisms of change.10 Describing the intervention using a theory of change and a log frame sets out causal assumptions. The theory of change then forms the basis of the process evaluation.

Example of a theory‐driven approach to evaluation of training in dermatology

A dermatology registrar noticed that she received regular inpatient referrals for patients with red legs suspected to have cellulitis, which often turned out to be venous eczema and thus simple to treat once the correct diagnosis had been reached. She wanted to implement a training programme for junior colleagues in Medicine in her hospital.

She put together a presentation on the subject, focusing particularly on how to differentiate between cellulitis and venous eczema, and topical therapy to treat the latter. She arranged to deliver it at the next general (internal) medicine training day and at the regular teaching to foundation doctors, knowing that this would capture most of the individuals who tended to make referrals to dermatology. It might have been useful for her to speak to colleagues or to explore literature on why these avoidable referrals happened, so that she could tailor her education and training. She knew that feedback on the session – how useful was it perceived to be and how well she presented it – would be collected on the day, but she really wanted to know whether it actually led to a change in practice.

Defining ‘avoidable’ as cases in which the diagnosis and management of venous eczema was clinically straightforward, she decided that she would audit the number of avoidable inpatient referrals for red legs to the on‐call dermatology service for a month before and a month after her teaching sessions. Here, she has specified a behavioural outcome.

In the month before the sessions, 10 referrals for red legs occurred, of which the dermatologist deemed 5 avoidable. In the re‐audit after the intervention, there were 12 referrals for red legs, 5 of which were deemed avoidable. Although her teaching had been well rated at the time (Kirkpatrick lower levels), she was left wondering whether it had made any difference and why it had not led to lower levels of avoidable referrals. In other words, she was now thinking about her theory of change.

She discussed the findings in a departmental meeting. She realized that her Medicine colleagues often suspected the correct diagnosis but reported that they lacked the confidence both to treat it as such and to wait for the treatment to take effect.

She wrote down her theory of change and reviewed her teaching session. She added questions to the evaluation that asked participants to rate their confidence about treatment before and after the session. She also included an evaluation focus group at the end of the training where colleagues discussed their intended changes in practice. A re‐audit suggested an improvement. With only two out of eight avoidable referrals, the rest of the cases either turning out to be refractory disease, or atypical/alternative diagnoses.

Conclusion

When developing and evaluating an educational intervention, there is often a focus on increasing what learners know; however, knowledge alone will not change behaviour. A good understanding of the barriers and facilitators to the behaviour that the intervention is targeting can enable the generation of a theory to guide development of the education and its subsequent evaluation. Such a behavioural approach can help to improve education and evaluation, making clinical change more likely and subsequently improving patient care.

Top tips when preparing education and training

Understand the problem by identifying or measuring the behaviour(s) that need to be changed.

Get a good understanding of the influences on each behaviour by speaking with the target healthcare professionals.

Apply theory when developing the intervention to target some of these influences of behaviour and specify this in a logic model or theory of change.

Evaluate the intervention using objective or subjective measures to understand whether the behaviour or its influences have changed.

Evaluation of education and training should be linked to the purpose of education and training.

It is useful explicitly to state both the intended outcomes of the education and a theory of change, and to evaluate these.

There are processes and guidelines to support robust and useful evaluation including COM‐B Framework, process evaluation, complex intervention evaluation, log frames and the Kirkpatrick model.

A feedback loop from evaluation into teaching development can help in the quality improvement of education and training.

Evaluating and quality improving education and training, particularly using behavioural theories, could make practice change more likely and thereby improve patient outcomes.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

None.

Ethics statement

Ethics approval not applicable. The patient provided informed consent for publication of their case details and images.

Data availability

Data are available on request from the corresponding author.