The Graves of Tarim: Genealogy and Mobility across the Indian Ocean

The Graves of Tarim: Genealogy and Mobility across the Indian Ocean

Contents

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Visiting the Graves of Tarim Visiting the Graves of Tarim

-

Who's Who: Engraving History Who's Who: Engraving History

-

The First Fātiḥa The First Fātiḥa

-

The Second Fātiḥa The Second Fātiḥa

-

The Third Fātiḥa The Third Fātiḥa

-

A Light Like Rain: Graves of Tarim, Gardens of Paradise, Genealogies of Diaspora A Light Like Rain: Graves of Tarim, Gardens of Paradise, Genealogies of Diaspora

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Cite

Abstract

This chapter examines Ahmad al-Junayd's localist project of restoring the houses, mosques, and graves of the ancestors in Tarim. It discusses his other work of writing manuals that could guide pilgrims in and around Tarim graves. It suggests that this is an example genealogy acquiring a bending power, curving the journeys of persons back to the graves of Tarim and contends that that power builds on the genealogical canon that developed in the diaspora.

In downtown Singapore, ten minutes' walk toward the sea from the gleaming, golden skyscrapers of the ministry of finance and the central bank, lies the grave of the Hadrami sayyid Ḥabīb Nūḥ al-Ḥabshī. The building that houses the grave is shaped more like a Hindu chandi than a Muslim saint's tomb; it is a rectangular structure rising many dozens of steps above the ground. The tomb within is covered by the green cloth of Islam and surrounded by golden yellow drapes, the color of Malay royalty. Pilgrims and supplicants from all ethnic groups—Malays, Hadrami Arabs, Chinese, and especially Indians—come to visit and sit quietly a while. On the walls are framed genealogies, pointing to Ḥabīb Nūḥ's siblings in Penang, Singapore's predecessor port city at the northern end of the Strait of Melaka, and to ascendants in Hadramawt. The line from Singapore to Penang reaches west to other port cities, which, until two generations ago, were Crown Colonies of Britain's empire of free trade: Colombo, Bombay, and Aden. Along this old trunk route of world trade, and along the smaller branches that feed into it, are older ports settled by Hadramis and housing tombs like Ḥabīb Nūḥ's. Indeed, we can visualize the diaspora of Hadramis as a distribution of graves across the Indian Ocean.

Yet the diversity of the visitors to these graves, as at Ḥabīb Nūḥ's in Singapore, mean that this diaspora cannot be understood in singular ethnic terms. Not all pilgrims come seeking their ancestors or origins. Like the British diaspora, which in its incarnation as an imperial power proclaimed its protection of free trade and the law for all comers in the nineteenth century, leading Hadrami figuresoften stood for causes larger than those of their own communities. Liberal state and universal religion come together in one corner of Ḥabīb Nūḥ's tomb, where the Singapore government has placed a locked steel safe with a slot to receive the votive offerings of pilgrims in publicly accountable fashion. Many parties participate, and distribution has to be fair. The port cities of the Indian Ocean were such plural societies. In chapter 4, we saw the sayyid Zayn al-ʿAydarūs leading Surat in prayer at the easing of a naval blockade that had gripped the entire city in crisis. In chapter 5, we saw how the traveling genealogies of the Hadrami sayyids had to bear the universal Light of Islamic prophethood and lent mystical shape to ecumenical Islamic society expanding across the Indian Ocean. And in chapter, those genealogies became intertwined with Bugis and Malay ones, in moral exchanges that created creole communities and transcultural families. As the diaspora moved, the genealogies evolved.

Steps to Ḥabīb Nūḥ al-Ḥabshī's Indianstyle shrine, Singapore. Photo by the author.

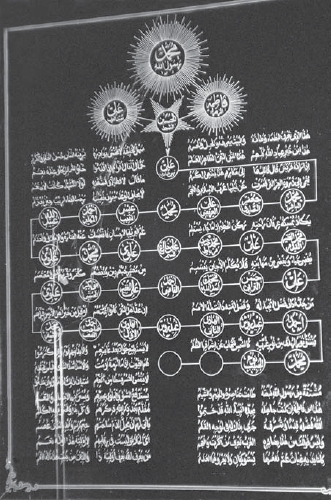

Lineal genealogy beside the tomb of Ḥabīb Nūḥ al-Ḥabshī, linking him to ascendants in Hadramawt and to Prophet Muḥammad. Photo by the author.

Those genealogies have two important dimensions: while they enable the tracing of origins, they also allow communities of diverse origins to articulate with each other in new relations of mutuality and moral engagement, such as in shared family and shared religion. This duality involves cohabitation of closed and open aspects, or, in the more specific terms of kinship, of patrilineal and matrilateral ties. Gender asymmetry is centralto this cohabitation, as we saw in chapter 6: holding the two sides together successfully turns on controlling women's choices in marriage. The theory to support such control appeared in canonical texts written abroad, such as al-Shillī's legally inflected genealogy/biography, The Irrigating Fount. At stake in this duality of closedness and openness was not a static tension but a dynamic of signification, which maintained discursive control over an expanding sphere of exchange rather than reject or throttle it. A diaspora, in this sense, provides characteristic ways of marking the movements of individuals, of presiding over the comings and goings of numerous persons across space, time, and culture.

Our examination of the evolving canon in diaspora noted a shift from figural to literal genealogies, embodied in the difference between ʿAbd al-Qādir al-ʿAydarūs's mystical The Travelling Light and al-Shillī's legalistic The Irrigating Fount. The move is again one from openness to closedness, but as the diaspora expands, so does what the enclosure contains. The different literary sensibilities of ʿAbd al-Qādir al-ʿAydarūs and al-Shillī, demonstrated in the way each handles genealogy, color their descriptions of the homeland Tarim as well. Both call for visiting the graves of Tarim, but while ʿAbd al-Qādir al-ʿAydarūs's account is short, mythological, and folkloric (al-ʿAydarūs 1985: 76), al-Shillī's is positivistic, systematic, and prescriptive (al-Shillī 1901: 148–49). In a section devoted to the mosques, cemeteries, hills, and wadis of Tarim, al-Shillī encourages a return to the town by embedding in his description a manual for visiting its graves. He instructs the reader to visit the grave of the First Jurist before anyone else's. He proceeds to detail a list of graves to visit, in less than a page. But his manual then stops abruptly, for he says that those far away will not benefit from his instruction, while those living there could easily find a reliable guide.

Like the diaspora, society in the homeland is also plural, composed of different groups and categories of persons, engaged in relations of exchange. In his book, al-Shillī has a non-sayyid, a Bā Harmī shaykh, say that without first visiting the First Jurist's grave, a pilgrimage is not valid. Just as Hadrami sayyids entered into exchanges with Indians in Surat and Bugis in Pontianak, in the new polities of the diaspora, so too in the homeland did they engage with other townsmen—tribals, farmers, and builders—in relations of exchange. From afar, the density of such exchanges makes them opaque, and al-Shillī abandons his effort at representing them. Furthermore, as we have seen, al-Shillī narrowed the scope of genealogy, refocusing it along the Prophetic patriline and allowing numerous lateral ties to fall away.

In this chapter, we return to Aḥmad al-Junayd, whom we left at the end of chapter 3, and examine this resolute localist's project of place making: restoring the houses, mosques, and graves of the ancestors. As part of that project, al-Junayd also wrote a manual for visiting the graves of Tarim. As one of the reliable locals, like those recommended by al-Shillī, he sought not to provide a description for visitors from far away but to create a text that could guide pilgrims in and around those graves. The text was a manual, a guide to proper action, and was part of his project to make Tarim a place of return. Here, we see genealogy acquiring a bending power, curving the journeys of persons back to the graves of Tarim. That power builds on the genealogical canon that developed in the diaspora, even borrowing from and extending the manual that al-Shillī had begun but abandoned. Al-Junayd's manual makes return a performance of pilgrimage to the graves of Tarim. As we have come to expect from al-Junayd, the stakes are large. After all, he wanted his brother back from Singapore for good. The poetics of pilgrimage brings together people who, in the course of the return, become a community. It concretizes such a community in a visit to the grave, in which the living call out the names of the dead, following the manual, and exchange greetings with them. As a place where mobile texts and mobile persons meet, the grave becomes a site where the resolute localist finds much work to be done and meaning to be invested. Considering al-Shillī's emphasis on the closed aspect of genealogy, what seems surprising here is that in the heart of the homeland, at the graves of Tarim, the open aspect of genealogy gains prominence again, in al-Junayd's manual. This prominence is less surprising if we recall that Hadramawt was initially a destination, rather than an origin, for the sayyids. In his concern with revivifying the traces of the ancestors, al-Junayd preserves something of that sense of Tarim as a diasporic destination. As we have seen in the travels of part I, much transcultural work needs to be done in the diaspora. It turns out that the same is true of the homeland as well, for within it, native status, aṣāla, is endlessly relative, layered, and deferred. In al-Junayd's manual for visiting the graves of Tarim, that transcultural work is again of a genealogical sort but now in a different, performative register: genealogy becomes pilgrimage. In pilgrimage, genealogy opens up the graveyard by expanding its space into an itinerary of ritual stations, and thereby increases its interpretive possibilities. Recognition of that interpretive amplification sensitizes one to the social complexities of the homeland and reveals it to be no less plural and complex than the diaspora, as we shall see.

Visiting the Graves of Tarim

The graveyards of Tarim are three: Zanbal, al-Furayṭ, and Akdar. At the edge of town, just within the old town wall, they lie on either side of a road that is also a wadi bed.1 The floods, when they come, pass through this major channel to water the gardens surrounding the town. It is well known that the water arrives in seven timed surges over a number of hours, due to the specific distribution of branches feeding this main channel upstream. What is unknowable is whether the rains will come at all. It is along the sides of this artery, by the graves, that men stand during prayers for rain (ṣalāt al-istisqāʾ), led by religious leaders of the town. In 1993 and 1994, they said such prayers during an extended drought. People say that such prayers will not work if men's hearts are not clean, if they harbor ill will toward each other. The prayers enjoin the townsfolk to concentrate not on what divides them but on what they have in common. The location of the prayer for rains is apt for this purpose. The gathering of the living is reflected in the society of the dead beside them. The men praying for water all have ancestors here who share the earth waiting for eternal relief. The two societies meet and mingle on such portentous occasions, and do so regularly. Every Friday, some individuals visit the graves. Every year, on the fourteenth of the month of Shaʿbān, after the largest annual pilgrimage, to the tomb of the prophet Hūd, visits are organized to the graves of Tarim, and visitors place sweet-scented basil at the headstones. As with prayer, such visits have leaders who head, guide, and chant. These leaders are normally the preeminent sayyid scholars of Tarim. The itinerary and liturgy of such visits among the ancestral remains trace out specific ways in which dead and living, sayyid and non-sayyid, relate to one another in one grave society, one town, one religion, and one history.

A number of manuals for the visit have been written and are incorporated into the diasporic texts, as we have seen (al-ʿAydarūs 1985; al-Haddād n.d.; al-Shillī 1982; Kharid 1985). But the most popular one in use today is the Salve for the Sickly in Organizing Visits to Tarim's Cemetery,2which Aḥmad al-Junayd wrote in the nineteenth century out of concern for the traces of the ancestors. It exists in many manuscript recensions produced for personal use. One version that I consulted had a colophon indicating that the owner was licensed in its use by a teacher.3 While such authentications of transmission are common, in this case the evidence of transmission is crucial to the nature of the text. By itself, the volume is of no use. One needs a guide who has prior knowledge of the graveyard and who will walk the visitor through both text and cemetery, pointing to the referents on the ground. Without such a guide, entering the graveyard with the manual is like coming upon a strange town with a map consisting only of an alphabetical list of street names. Aḥmad al-Junayd was urged by his contemporaries to write the manual because he had frequently accompanied his teacher the sayyid ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. ʿAbd Allāh Bā Faraj around the graveyards of Tarim and had been shown the graves of the famous pious. When the teacher died, al-Junayd's community wanted to preserve his great knowledge of the tombs. Aḥmad was able to write down that knowledge and to pass it on as a guided tour. In this sense, the knowledge exists in the inseparable conjunction of teacher and text and is reproduced as a performance in real space and time—as educational tourism in the city of the dead. Some of the tombs had multiple inhabitants, and Aḥmad pointed them out as well. The cemetery provides another reason for thinking of knowledge as personal contact and for representing it in genealogical form. Let us now consider the knowledge that is inculcated through the itinerary of the text. We follow the recension of ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Mashhūr, whose abridgment of his teacher Aḥmad al-Junayd's Salve is the version commonly used. This recension, the Gift of the Generous Intimate for Visiting Tarim's Saints, is the slimmer version that is hand-copied and taken round the tour.4

The manual begins with a direct prescription:

It behooves the visitor to begin at (the grave of) the First of the cemetery, our master the First Jurist, and say: Greetings to you, Oh Saints of God! Greetings to you, Oh Best of God! Greetings to you, Oh Elect of God! Greetings and the mercy of God be upon you! … Greetings to you, Oh Folk of the Graves, may you receive what you have been promised, and God willing we will follow. We ask God for us and for you health.5 Oh God, make enter among them spirit from you and greetings from us. Greetings to you, Oh Folk of “There is no god but God”6 (repeated a number of times with variation). … Greetings to you, our brothers of the Muslims and the believers. May God bless you, the ancient and the recent … tame your wildnesses … be merciful to your absence … record your virtues … forgive your transgressions …

The visit to the graves is opened at the first station, the grave of the First Jurist (al-Faqīh al-Muqaddam) Muḥammad b. ʿAlī. We met him in chapter 2. He is the unique first point where Prophetic descent and organized Sufism come together in Hadramawt. The scholarly etymologies agree that the attribution of precedence in his title refers directly to his position as the first figure in the graveyard to be visited on such occasions. Yet the sense of the “Paramount Jurist” is buttressed by his other title, the Greatest Teacher (al-Ustādh al-Aʿẓam), and underscores his orthodoxy, as an exponent of religious law. This stamp is important because of the First Jurist's hand in introducing Sufism to Hadramawt; the law and Sufism have often been pitted against each other in Islamic history (al-Ḥibshī 1976; Memon 1976). The First Jurist received the investiture (taḥkīm) from a courier dispatched by the Maghrebian saint of Telemcen, Abū Madyan Shuʿayb, in the thirteenth century; on his shoulders was placed the mantle (khirqa) of Abū Madyan. His contemporary al-Shaykh Saʿīd bin ʿῙsā al-ʿAmūdī, of Dawʿan at the western end of Hadramawt, also received the investiture of Abū Madyan. Opinions differ about whether the First Jurist or al-ʿAmūdī first received the investiture directly from the courier and passed it on to the other. The First Jurist was the first to denounce violence and the use of arms, breaking his sword over his knee. This action inaugurates the sayyid tradition of pacifist Sufism and became a major plank in sayyids' self-identification as independent arbiters of the peace between armed tribes. Al-ʿAmūdī himself is visited in a popular annual pilgrimage, but his descendants carry arms and ruled parts of the western end of the wadi intermittently over centuries.7

The descent line of the Hadrami sayyids begins to branch at the First Jurist. Most sayyid descendants are his progeny, while a small minority revert to his father's brother, who is known as the “Uncle of the Jurist (ʿAmm al-Faqīh). Significantly, visits to the graves of Tarim begin with the grave of the First Jurist rather than with that of his great-grandfather ʿAlī the Endower of Qasam (d. 1135 c.e.), who was the first sayyid buried in Tarim. While genealogical descent is one ordering modality of a visit to the graves, the Sufi complex initiated by the First Jurist organizes the orthopraxy of religion itself in Hadramawt. Visits to the graves are thus also construed as visits by Sufi initiates to their masters. In this sense, a visit is merely an extension of calls made to teachers for instruction while they were alive and is an affirmation of the perduring pedagogical relation. Correspondingly, the “First” to be visited is also the “Greatest Teacher.” Indeed, as we will see in the next chapter, pilgrimages to the tombs of saints are combined with and assimilated into visits with living scholars, in return journeys of creoles to the homeland. The educational tourism of the visit to Tarim's graves is one moment in an ongoing didactic process of ambitious proportions. This school began with the First Jurist (d. 1255), eight generations or three hundred years after the advent of his ancestor Aḥmad b. ʿῙsā the Migrant (d. 956) in Hadramawt, the first sayyid to settle there and arguably the progenitor of the largest Hadrami tribe.

At the First Jurist's grave, the visit opens with two exchanges between the living and the dead. All of the living, regardless of social affiliation, stand in one rank, as a moiety facing all of the dead, as their opposite. First is the exchange of greetings. The greetings to the dead are a call for their presence. The question of whether they reply is the subject of much discussion; the old texts are replete with instances in which they do. Second is the repetition of the first line of the Muslim declaration of faith, “There is no god but God” (Lā ilāha illā Allāh), as a gift to the souls of the departed. The declaration is named by the onomatopoeia tahlīl, and its repetition bestows merit upon the dead. Pious, wealthy Hadramis leave trusts in their wills specifically for the annual performance of the tahlīl, for the sake of their own souls, and as gifts to their deceased relatives, followers, servants, and slaves. The endowment pays for the coffee and incense used on such occasions. The arrangement is one pious act that endures after death—a pious son praying for one's soul, as the Prophet said.

At the cemetery, the dead are accorded powers in various degrees, typically thaumaturgic in nature: thus the title of Aḥmad al-Junayd's manual, Salve for the Sickly. The hagiographies of many of those lying in this graveyard reveal that requests asked of them will be answered, and in the course of the visit, requests are made. In parallel with the pedagogical ambition, the visit is also one moment in an ongoing process of votive exchanges that brings together living and dead in a relation of supplicant to saint.

The pedagogical and votive aims of the visit are pursued within a poetic structure whose performance is scripted in the manual. The iterative process of its movement enables us to highlight the formal elements of that structure by way of a summary. The linear motion of the ritual through written and performed time is marked at various points by paradigmatic figures, of whom the first and the prototype is the prophet Muḥammad. The plots where these figures lie buried or are invoked are the major stations of the visit; between them are minor ones. These figures are surrounded by associates, followers, and dependents in a circle, as it were. Across the historical and performative times that separate them, the major figures are brought into paradigmatic consociation by ritual invocations shared only by them. These utterances create a resonance between the figures, raising them above the smaller individuals who surround and separate them and creating landmarks on the ritual terrain. Between these landmark figures, movement takes on a linear appearance. In the early part of the text, the progress is genealogical, chain-linking fathers and sons in a single, unbroken, vertical line of patrilineal descent. Subsequent parts abandon the genealogical line, and the linearity takes form in corporeal movement on the ground, as visitors move down rows of graves, enfilading laterally. In this phase, successive stations in the textual itinerary are guided by locations on the ground. Here, the order of the sequence does not imply generational or hierarchical precedence but is simply an accident of burial location. Each station, however, reiterates both the linear and circular elements in the form of mini-genealogies and collateral lines of the residents of the plots, and through evocation of an orbit of kinsmen, associates, teachers, and followers. In the course of the visit, visitors may invoke individuals a number of times by name, as they are emplaced in related genealogies and overlapping clusters of associations. Repetition of their names within different groups reinforces familiarity and creates a sense of sociability among the dead. The overall effect is of an imbricated series of spirals, formed by the liturgical dynamic of vertical, circular, and lateral elements. The resulting movement of bodies, voices, and minds across the graveyard, analogous to that of a slow-moving tornado, if an image is desired, actualizes a commingling of persons and groups, dead and alive, in the shared time and space of the visit to the graveyard. Visitors come to meet persons, and at their resting places, greet them and theirs by name. Together, the living and the dead are referred to as “the folk of this noble presencing (ḥafra).”8 The virtual collectivity enacted is not an amorphous amalgam; it is constituted in relations of generational precedence, hierarchical rank, filiation and agnation, tutelage, attachment, service, sepulchral distance, and so on.

The tombs of the ancestors are metonyms of relics that are consubstantial with them. Positioned on the earth of the grave, visitors stand in the presence of those they visit, in enfleurage, by a tactile logic of contiguity expressed in ʿAbd Allāh al-ʿAydarūs's formulation: “their places are directly in contact with their clothes; their clothes cover their bodies; their bodies clothe their souls, and their souls adorn the presence of their God … the fragrance of souls we find in their clothes” (al-Haddād n.d.: 71). The graveyard is a reliquary of the traces of the ancestors, which Aḥmad al-Junayd's choreography in his manual brings alive for the moving reciter. The number of names in the manual runs in the hundreds, and with classificatory extensions added, its scope is infinite: the family of so-and-so, root and branch; the family's neighbors; the folk of Jerusalem; all the scholars; all the saints; all Muslims. Even people not buried in Tarim can be incorporated. The poetic structure organizes them in a coherent fashion that, with familiarity, can even be memorized. This is less difficult than at first blush, as the organizing categories, families, and even individuals are already known from everyday social life, and from the regular rituals that texture it.

Recalling the pedagogical and votive aims of the visit, the manual has, coordinate with the form, messages conveyed in its contents. Two things predominate in the contents: history, and a cure. The history is of the arrival of the prophet Muḥammad's mission in Hadramawt and its deposition in Tarim, specifically in Tarim's preeminent graveyard, Zanbal, the resting place of the Prophet's descendants. Their tombstones stand erect as witnesses, marks in the engraving of that history. They make the mission locally present and available to the folk of Tarim, if they seek it. What is available is a cure for this world and the next, salve and salvation. One takes in the history with the cure.

Like the canonical texts we have read in their diasporic contexts, the contents of this history are shaped by the form of their presentation. The pilgrimage itself is the message. As such, our reading of that history is compelled to follow the paths traced around the graves of Tarim by al-Junayd's incantatory text, and by the pilgrims who lend its written words their bodies and voices. Let us see how form and content inform each other along the way.

Who's Who: Engraving History

At the grave of the First Jurist, al-Junayd's manual says to sit and recite the Yāsīn verse from the Qurʾan and the opening verse, the Fātiḥa, while leaving open the choice of other verses. After this recitation, the prayer for the Prophet, the taṣliyya of presencing, is enjoined. The Fātiḥa is then read for three major groups: first, prophets and descendants of the prophet Muḥammad, in chronological order down to the early twentieth century; second, the shaykhly lineages of Hadramawt, families that have some historical religious fame and standing but are not descended from the Prophet; third, a global Muslim community comprising the founders of legal schools in Islamic law, famous Sufi figures, and others.

The order of the three Fātiḥas at the first station initiates the spiral patterns that are subsequently recapitulated at each unit station. There is an emphatic vertical axis—a lineal genealogy—surrounded by a circle of followers. At the first station, the axis is the line of the prophet Muḥammad (first Fātiḥa), followed by the circle of local followers (second Fātiḥa) and then the maximal circle of the global community of Muslims (third Fātiḥa). This order also anticipates the overall sequence of the entire visit. First, the visit works its way through the cemetery of the sayyids, Zanbal; then it moves on to that of the shaykhs, al-Furayṭ; and in closing, it invokes all Muslims in a grand finale of benedictions. Considered within the total poetic structure of the visit, then, the three Fātiḥas of the first station are a part that can stand for the whole, a synecdoche for the cadaveral and living body of Muslims of Tarim and the world, headed by the prophet Muḥammad and his descendants. At this signal point, within the poetic representation is the content of a history lesson, a message elaborated in detail. We have seen something of this message in chapter, in the formation of the ʿAlawī Way in the homeland and the routes thereto. Here we pick up that thread again, now on its own narrative terms and its preferred stage, the graves of Tarim. Table 2 highlights the key personages inthe discussion to follow.

| Year of Death . | Name . | Significance . |

|---|---|---|

622 | I. Prophet Muḥammad | Prophet of Islam, ancestor of all sayyids |

Prophet Hūd and other prophets | ||

| | ||

956 | Aḥmad b. ʿĪsā the Migrant | Founding ancestor of sayyid line in Hadramawt |

| | ||

ʿAlawī b. ʿUbayd Allāh | Eponymous ancestor of all Hadrami sayyids | |

| | ||

1135 | ʿAlī Endower of Qasam | First sayyid buried in Tarim; founder of Qasam town near Tarim and investor in its productive date palms |

| | ||

1161 | Muḥammad Principal of Mirbāṭ | The ancestor in whom all Hadrami sayyid genealogical ascent lines meet |

| | ||

1255 | II. The First Jurist | Initiator of sayyid, Sufi ʿAlawī Way |

| | ||

1416 | III. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Saqqāf | Originator of ritual forms that mark the beginning of the institutionalized ʿAlawī Sufi complex |

| | ||

1430 | IV. ʿUmar al-Muḥḍār | Originator of geographical form (sanctified landscape); first leader of a formal sayyid association |

\ | ||

1451 | Muḥammad b. ʿAlī Kharid | Author of first major sayyid genealogy |

\ | ||

1461 | ʿAbd Allāh al-ʿAydarūs | “Sultan of Notables”; progenitor of al-ʿAydarūs lineage, the lineage most famous abroad and with the greatest number of sovereign settlements at home |

\ | ||

1490 | al-Shaykh ʿAlī b. Abī Bakr al-Sakrān | First sayyid author of biographies |

\ | ||

1513 | Abū Bakr al-ʿAydarūs the Adeni | Saint of Aden; founder of first translocation of the sayyid Sufi complex outside Tarim |

\ | ||

1561 | Aḥmad b. Ḥusayn al-ʿAydarūs | Founder of the first sovereign settlement under a sayyid (manṣabates) |

\ | ||

1584 | Shaykh Bū Bakr bin Sālim | Founder of the ʿAynāt manṣabate; reorganized Hūd pilgrimage. Father of al-Ḥusayn, who brought Yāfiʿī mercenaries to repel the northern Qāsimī imams |

\ | ||

1720 | V. ʿAbd Allāh al-Ḥaddād | Distinguished saint of Tarim and author of widely used books and liturgies |

\ | ||

Ḥasan Ṣāliḥ al-Baḥr | Associate of the three men below who repelled Yāfiʿīs from Hadramawt | |

Ṭāhir b. Ḥusayn bin Ṭāhir | The only person to attempt to establish a sayyid state (imamate) with arms | |

ʿAbd Allāh b. Ḥusayn Bilfaqīh | One of “the Seven ʿAbd Allāhs” | |

1858 | Aḥmad b. ʿAlī al-Junayd | Author of the manual for visiting the Tarim graveyard, Salve for the Sickly |

\ | ||

1902 | ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Mashhūr | Author of an abridged version of al-Junayd's manual; author of the “total” sayyid genealogy The Luminescent, Encompassing Mid-day Sun |

| Year of Death . | Name . | Significance . |

|---|---|---|

622 | I. Prophet Muḥammad | Prophet of Islam, ancestor of all sayyids |

Prophet Hūd and other prophets | ||

| | ||

956 | Aḥmad b. ʿĪsā the Migrant | Founding ancestor of sayyid line in Hadramawt |

| | ||

ʿAlawī b. ʿUbayd Allāh | Eponymous ancestor of all Hadrami sayyids | |

| | ||

1135 | ʿAlī Endower of Qasam | First sayyid buried in Tarim; founder of Qasam town near Tarim and investor in its productive date palms |

| | ||

1161 | Muḥammad Principal of Mirbāṭ | The ancestor in whom all Hadrami sayyid genealogical ascent lines meet |

| | ||

1255 | II. The First Jurist | Initiator of sayyid, Sufi ʿAlawī Way |

| | ||

1416 | III. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Saqqāf | Originator of ritual forms that mark the beginning of the institutionalized ʿAlawī Sufi complex |

| | ||

1430 | IV. ʿUmar al-Muḥḍār | Originator of geographical form (sanctified landscape); first leader of a formal sayyid association |

\ | ||

1451 | Muḥammad b. ʿAlī Kharid | Author of first major sayyid genealogy |

\ | ||

1461 | ʿAbd Allāh al-ʿAydarūs | “Sultan of Notables”; progenitor of al-ʿAydarūs lineage, the lineage most famous abroad and with the greatest number of sovereign settlements at home |

\ | ||

1490 | al-Shaykh ʿAlī b. Abī Bakr al-Sakrān | First sayyid author of biographies |

\ | ||

1513 | Abū Bakr al-ʿAydarūs the Adeni | Saint of Aden; founder of first translocation of the sayyid Sufi complex outside Tarim |

\ | ||

1561 | Aḥmad b. Ḥusayn al-ʿAydarūs | Founder of the first sovereign settlement under a sayyid (manṣabates) |

\ | ||

1584 | Shaykh Bū Bakr bin Sālim | Founder of the ʿAynāt manṣabate; reorganized Hūd pilgrimage. Father of al-Ḥusayn, who brought Yāfiʿī mercenaries to repel the northern Qāsimī imams |

\ | ||

1720 | V. ʿAbd Allāh al-Ḥaddād | Distinguished saint of Tarim and author of widely used books and liturgies |

\ | ||

Ḥasan Ṣāliḥ al-Baḥr | Associate of the three men below who repelled Yāfiʿīs from Hadramawt | |

Ṭāhir b. Ḥusayn bin Ṭāhir | The only person to attempt to establish a sayyid state (imamate) with arms | |

ʿAbd Allāh b. Ḥusayn Bilfaqīh | One of “the Seven ʿAbd Allāhs” | |

1858 | Aḥmad b. ʿAlī al-Junayd | Author of the manual for visiting the Tarim graveyard, Salve for the Sickly |

\ | ||

1902 | ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Mashhūr | Author of an abridged version of al-Junayd's manual; author of the “total” sayyid genealogy The Luminescent, Encompassing Mid-day Sun |

note: The central column contains names invoked in al-Mashhūr's liturgy Gift of the Generous Intimate for Visiting the Tombs of Tarim's Saints. The grave of the First Jurist (II) is the first station of the visit to the graves. Here, visitors read the Fātiḥa chapter of the Qurʾan for the souls of the people in this table. The names numbered I to V are ritually elevated in the liturgy. I have added information that does not appear in the manual: the year of death and the person's historical significance. Vertical lines between names denote unbroken genealogical progression, whereas slashes indicate jumps in the genealogy, moving sideways to collateral lines and downward to descendants.

The First Fātiḥa

First, the Fātiḥa for his Presence our Sayyid (master) the Prophet of God Muḥammad son of ʿAbd Allāh, God's prayers be upon him, and upon the Prophet of God Hūd, and all the Prophets and Messengers all of them, and upon their companions and followers until the Day of Reckoning.

The first Fātiḥa opens with Prophet Muḥammad (I in table 2) and Prophet Hūd. It mentions the first four caliphs after Muḥammad, as well as members of his family: his daughter Fāṭima and her sons Hasan and Ḥusayn, his wives Khadīja and ʿAʾisha, his uncles ʿAbbās and Hamza, and ʿAbbās's son ʿAbd Allāh. Broader categories—of Prophet Muḥammad's wives, descendants, all scholars, and all saints—are invoked. The litany then moves in a direct unilinear progression of the sons of Ḥusayn (Muḥammad's grandson) until Aḥmad b. ʿῙsā the Migrant, the ancestor of all Hadrami sayyids. The parsimonious chain-linking of his descent from Ḥusayn, without collaterals, asserts the truth and force of his extraction. Reaching the Migrant in the progression recalls his circle of brothers, sons, and grandsons. The descent lines of his sons and grandsons went extinct except for that of the grandson ʿAlawī b. ʿUbayd Allāh, the eponymous ancestor of the sayyids of Hadramawt. Thus, this lineage group is also known as the Folk of Father ʿAlawī (Āl Bā ʿAlawī), or ʿAlawīs (ʿAlawīyyūn).

Past ʿAlawī, the genealogical recitation proceeds with no break to ʿAlī the Endower of Qasam. As we have seen, ʿAlī the Endower reputedly founded the settlement of Qasam by investing 20,000 dinārs in planting date palms, bringing value to the land. The Endower of Qasam is the first sayyid to be buried in Tarim, and his burial initiated their presence there. Historically, he stands for the settlement of the sayyids in Tarim. The Endower's son is known as Muḥammad Principal of Mirbāṭ, a town on the Indian Ocean coast, where he is buried. All living Hadrami sayyids are descendants of Muḥammad the Principal of Mirbāṭ; their lines of ascent meet in him.

The domiciling of the sayyids in Hadramawt took three centuries from the time of the Migrant's arrival, finally being fixed only with the First Jurist (II in table 2), the eighth-generation lineal descendant of the Migrant, seventeen generations following the prophet Muḥammad. The manual for visiting the graves scrupulously recounts all the generations from the Prophet to the First Jurist with no omissions, until it reaches Abū Bakr al-ʿAydarūs the Adeni (see table 2).

Four generations past the First Jurist, his lineal descendant ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Saqqāf (III in table 2) is the next major figure in the litany. He stands at the beginning of a new phase in the history of the ʿAlawī Way: the development of an institutional complex of Sufi practices, comprising ritual, geographical, and textual elements. Al-Saqqāf initiated rituals still practiced today. His son, ʿUmar al-Muḥḍār (IV in table 2) is linked to significant places on the ritual landscape: Umar's Rock, the first station at the pilgrimage to the prophet Hūd's tomb, by the perpetual stream; and al-Muḥḍār's mosque, where the fasting month of Ramafān is brought to conclusion.

Another figure, ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Khaṭīb (d. 1451), appears a number of times in the manual, though he is not represented in table 2. We have met him in chapter, as the author of the Garden of the Heart Essences, Apothecary for Incurable Maladies (subsequently renamed the Transparent Essence), the foundational compilation of Hadrami Sufi biographies upon which subsequent canonical authors, such as ʿAbd al-Qādir al-ʿAydarūs and al-Shillī, drew copiously. While al-Khaṭīb was not a sayyid, his text, along with al-Muḥḍār's places and al-Saqqāf's rituals, brought together the institutional complex of the ʿAlawī Way in the mid-fifteenth century.

A cluster of significant figures in the manual is the ʿAydarūses, some of whom we have met. ʿAbd Allāh al-ʿAydarūs, a grandson of al-Saqqāf who was raised by his uncle al-Muḥḍār, appears as the Sultan of Notables in the manual. He was nicknamed al-ʿAydarūs by his grandfather and fostered the lineage of that name, which became famous away from Tarim, in surrounding regions and in Aden, India, and elsewhere. The Saint of Aden, Abū Bakr al-ʿAydarūs the Adeni, is called out here, as is Aḥmad b. Ḥusayn al-ʿAydarūs (d. 1561), who founded the first settlement in Hadramawt under a form of sayyid sovereign rule (manṣab), while his brothers prospered in India. A number of manṣabates subsequently developed around Tarim under the leadership of other ʿAydarūses, in plantation settlements such as Thibī, Būr, Tāriba, and al-Hazm that were funded by remittances from India. This usage of the term manṣab is not found elsewhere in the Arabic-speaking world and may be an adoption of Indian usage. As a result of these linked expansions abroad and at home, the ʿAydarūs family became the grandest of the sayyid lineages. The family's eponymous ancestor ʿAbd Allāh al-ʿAydarūs, father of the Adeni, is thus invoked with the honorific Sultan of Notables in the graveyard manual.

Other major figures in the manual have similar transregional presences. Shaykh Bū Bakr bin Sālim, who appears in table 2 after the ʿAydarūses, is not buried in Tarim, like the Adeni. From the family base at ʿAynāt, a town forty minutes today by car from Tarim, the lineage of Shaykh Bū Bakr has had a transregional presence beyond Hadramawt since the late sixteenth century. In 1584, Shaykh Bū Bakr deputed ʿAlī Harhara, one of his students, to the region of Yāfiʿ near Aden to spread the ʿAlawī Way. Links between Shaykh Bū Bakr and the Yāfiʿīs have been strong since then, in a relation of spiritual clientage. In the seventeenth century, the Shaykh Bū Bakrs obtained Yāfiʿī assistance in expelling the northern Zaydi Qāsimī occupiers from Hadramawt; this was achieved in 1704. Besides creating alliances with the Yāfiʿīs, Shaykh Bū Bakr's son al-Ḥusayn was famous for his campaign against tobacco, as we saw in chapter. Abroad, Muslim sultans in the Comoro Islands in East Africa belonged to branch lineages of Shaykh Bū Bakr, as does the Raja of Perlis, who is now (2005) King of Malaysia. Before the advent of socialism in South Yemen, the Shaykh Bū Bakr lineage maintained an open kitchen as a public institution to host visitors and celebrate calendrical events. The family received annual votive offerings of coffee from the Yāfiʿīs and money from endowments in India for the upkeep of the kitchen. Shaykh Bū Bakr himself composed various litanies and Sufi works, as well as specific traditions that are practiced in Hadramawt today. For instance, he initiated the tradition of praying the five obligatory prayers all at once after noon on the last Friday of the fasting month of Ramafān. Shaykh Bū Bakr first started this tradition within his own family, but as his reputation grew, the practice spread, and people came from towns such as Sayʾūn, Tarim, and Qasam for these special prayers at ʿAynāt.9

A more purely religious figure, ʿAbd Allāh al-Haddād (V in table 2) was a relatively late saint of Tarim, living through the occupation of the northern Qāsimī imams; he died in 1720, a decade and a half after their expulsion. He was blind from an early age and is well known for his writings, which were among the first Hadrami printed texts (al-Haddād 1876, 1891, 1895, 1927) and are today translated into Malay (al-Haddād 1981, 1995 [1985]; Al-Husaini 1999), English (al-Haddad 1991; al-Haddad 1992), and French (al-Haddād 2002, 2004).

The last major grouping of sayyids invoked at the first Fātiḥa in the manual are the associates of Aḥmad al-Junayd, from the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. They were united in expelling the Yāfiʿīs from Hadramawt, who were associated with Shaykh Bū Bakr and came to dominate the region in the century after the expulsion of the Qāsimīs (bin Hāshim 1948; al-Kindī 1991; al-Mashhūr 1984:229 ff). Ṭāhir b. Ḥusayn b. Ṭāhir issued a call to arms and declared himself imam, the leader of an Islamic state. He drew, though not explicitly, on the northern, Zaydi model of a religiously guided descendant of the Prophet unsheathing his sword in a stand against oppression and injustice (Zayd 1981). The move broke with the pacifist tradition of his ancestor the First Jurist and was controversial. The experiment was short-lived, and Ṭāhir subsequently removed to the coast at al-Shiḥr, where he was an exile of sorts. His brother ʿAbd Allāh was one of seven scholarly contemporaries all named ʿAbd Allāh, who supported Ṭāhir. They came to be called the Seven ʿAbd Allāhs; ʿAbd Allāh b. Ḥusayn's grave at al-Masīla near Tarīm is visited annually. As an outgrowth of their histories, the lineages of Shaykh Bū Bakr of ʿAynāt and the bin Yaḥyās (of whom the Ṭāhirs are a branch) of al-Masīla are the only sayyids who are recognized as arms bearing.

The first Fātiḥa ends with the names of Aḥmad al-Junayd and his student ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Mashhūr, respectively the author and popularizer of the manual itself. Unlike the graves it visits, the manual is not a relic. Rather, like the genealogy within it, the text is a living process that develops and grows. In writing and editing it, al-Junayd and al-Mashhūr created a vehicle for their own perpetuation, as ancestors. In the end, they themselves were inducted into the liturgical genealogy by subsequent manuscript copyists of the manual.

As this account of the first Fātiḥa indicates, the names chanted in what at first blush appears to be a genealogical liturgy move seamlessly between religious and historical registers as well. At the grave of the First Jurist, and beginning with the prophet Muḥammad himself, these names of a Prophetic genealogy trace out known geographies and histories, abroad and at home, down to recent times, finally including the manual's authors, and their associates, at the end of the nineteenth century. They had created a political movement to rid Tarim of the Yāfiʿī interlopers who caused Aḥmad al-Junayd such misery and ultimately caused his brother ʿUmar to disavow returning to Tarim for good, choosing the security of Singapore instead.

The Second Fātiḥa

At the end of the first Fātiḥa, which is for the ʿAlawīs, the liturgy invokes recitations for a class of persons collectively known as shaykhs. Shaykh is a generic term in Arabic meaning “chief, elder, leader”; in the Sufistic context of Hadrami social history, it functions as an honorific, connoting a teacher and mentor to an initiate. Unlike the first Fātiḥa, the second has no overarching ordering principle such as genealogy or chronology. Rather, it is a list of religious notables, the majority of whom are considered indigenous to Hadramawt. These notables came from South Arabian groups that had been famous since pre-Islamic times, such as the tribes of Kinda, Madhḥij, and Banī Hilāl. A few families such as the al-ʿAmūdīstrace clandestine histories emerging in glorious origins, such as descent from ministersof the Abbasid empire (conventionally considered the high-water mark of Islamic civilization), which had to be concealed for fear of pursuit after a defeat. They have family names, like most Hadramis, and the names have a categorical stability spanning the past five hundred years, since at least the sixteenth century. The al-Khaṭībs, for example, have delivered the weekly Friday sermon at the congregational mosque in Tarimfrom those times until today. In Singapore, the most senior religious authority among Hadramis in recent years was an al-Khaṭīb, Shaykh ʿUmar, until his death in 1998. The word Khaṭīb itself means preacher.

Beyond ancient or clandestine origins, the shaykhly families historiographically trace descent to the first ancestor who had religious distinction and fame. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Khaṭīb's Transparent Essence, the compendium of Sufi biographies which became the founding text of the sayyid ʿAlawī Way, is the primary source for the ancestral “firsts” of the shaykh families as well. The Bā Faḍls began with Sālim b. Faḍl Bā Faḍl, in the twelfth century (d. 1185). In some accounts, he left Hadramawt at a time when the light of knowledge there was flickering and spent forty years abroad in Iraq studying (al-Ḥāmid 1968: 473). He finally returned with a camel-load of books and revived religious scholarship. He was so successful that in his time, Tarim had three hundred scholars, all students of his and all of them muftis. One of these students was the First Jurist (al-Ḥāmid 1968: 720). Shaykh Sālim b. Faḍl Bā Faḍl heads the liturgy of the shaykhs in the grave manual. The positions of the First Jurist and Shaykh Sālim Bā Faḍl as liturgical heads of their respective cemetery groups in the manual puts them in a relation of equivalence and connection, a notion that purified sayyid genealogical representations, such as those of al-Shillī, lose sight of. In Tarim in the early 1990s, the head of the Jurisprudential Opinions Council (Majlis al-Iftāʾ) was a Bā Faḍl: Shaykh Faḍl Bā Faḍl, a legist with a twinkle in his eye who was born in the Dutch East Indies and repatriated to Tarim for schooling as a boy. Another member of this family, Shaykh Ruḥayyim b. ʿAbd Allāh Bā Faḍl, was the teacher and informant of the preeminent British scholar of Hadramawt, R. B. Serjeant. He authored numerous accounts of pilgrimages to sites in the region (Ruḥayyim Bā Faḍl n.d.-a, n.d.-b, n.d.-c, n.d.-d, n.d.-e).

In recorded history, many of the shaykhly families, such as the Bā Marwāns, had religious reputations before the proliferation of sayyid scholars and saints around the fifteenth century. For example, the shaykh ʿAlī b. Aḥmad Bā Marwān was the teacher of the First Jurist, and he became angry when his student broke his sword and took up the mantle of the Maghrebian saint Abū Madyan. He appears early in the Fātiḥa for the shaykhs in the manual, as does another teacher of the First Jurist, Muḥammad b. Aḥmad b. Abī al-Hubb (Bā Wazīr 1961: 126). The invocation of Bā Marwān and Abī al-Hubb at the second Fātiḥa foreshadows their positions in the visit. After the visit to Zanbal, the sayyid graveyard, pilgrims are to visit the graveyard of al-Furayṭ, where the shaykhs are buried. Here, the tombs of Bā Faḍl, Bā Marwān, and Abī al-Hubb are the first three stations visitors encounter. Engaged in the continuous biographical process of teaching and learning, shaykhs and sayyids are found as teachers and students to each other. Some sources say that Shaykh Sālim Bā Faḍl was a student of the sayyid Muḥammad Principal of Mirbāṭ (al-Ḥāmid 1968:702; al-Shillī 1982), while others do not (al-Khaṭīb n.d.; Bā Wazīr 1961:118). Shaykhly families can decline in religious standing if they stop producing scholars of note. The Bā Rashīds are an example. They were known for the Bā Rashīd mosque, one of the oldest in Tarim, which was already standing when the Endower of Qasam and his family of the Prophet's descendants began settling there in 1127. Aḥmad b. Muḥammad Bā Rashīd was a rich man who built five mosques; he was also considered a saint. He is known as the Trader of This World and the Next. The biographies of the early sayyid saints are replete with references to the indigenous shaykhs. The mother of ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Saqqāf (who established basic rituals of the ʿAlawī Way; III in table 2) was the daughter of the shaykhly Trader of This World and the Next (al-Ḥāmid 1968: 757). AlSaqqāf's teacher was another shaykh, Muḥammad b. Abī Bakr Bā ʿAbbād (Bā Wazīr 1961: 134). Another Bā ʿAbbad, ʿAbd Allāh b. Muḥammad, a teacher of the First Jurist, practiced ascesis at the tomb of the prophet Hūd before the sayyids; because of his precedence, his descendants continue to be the custodians of the land of the prophet Hūd's tomb complex today, in association with the bin Kūb Tamīmī bedouin who live in the vicinity. Other shaykhly lineages have always been of lower standing, such as the Bā Harmī and Bā Gharīb lineages. They specialize in teaching children the basics of reading and memorizing the Qurʾan.

The Third Fātiḥa

Upon completion of the second Fātiḥa, a third is read for the souls of Muslims elsewhere, those not buried in Tarim nor otherwise associated with it. These begin with the founders of the four orthodox schools of Sunni Islam, the jurists al-Shāfiʿī, Malik, Aḥmad, and Abū Hanīfa. Next come the luminaries of Sufism, such as Abū Madyan Shuʿayb, ʿAbd al-Qādir al-Jīlānī, and al-Hasan al-Shādhilī. Although Abū Madyan is credited with being the master of the First Jurist, his location here reflects the social perspective of the manual and the visit, which gazes out from the locale of Tarim and its spiritual leadership. Positioning the jurists before the Sufis affirms the orthodoxy of the visiting congregation, as does positioning the invocation of Muḥammad al-Ghazālī (d. 1111) after those for both groups; al-Ghazālī is credited with effecting a reconciliation of law and mysticism. In the same vein, the name of Ibn al-ʿArabī is absent, despite his formative historical and doctrinal influence, for he is a controversial figure. Pilgrimages to the graves of Tarim shun controversy; they seek harmony instead.

The third Fātiḥa completes the first station of the visit. As a self-contained cycle within the liturgy that models the whole visit, it ends with prayers for the general desiderata:

God raise their rank in heaven and preserve us with their protection and extend to us their assistance and benefit us through their grace in this world and the next, with their eminence and their secrets. God forgive the sins ‖ make easy the required, sort out the affairs of the Muslims. Choose for us what's good, in contentment and submission. Grant us success, wherever and to whomever He desires; freedom from all sickness ‖. Give us sustenance as He did the followers of the prophet Muḥammad, grant us the imitation of his deeds, let us be formed by his character, grant us what he gifted to the pious ones. We give thanks to God. May He lengthen our lives ingood health; give us sustenance and a believing and obedient wife and good, blessed, pious descendants; a legitimate, healthful, ample livelihood, and complete belief. And makethis true for our parents and children and shaykhs and whomever has claims upon us; and whomever leaves us testaments of prayers; and all Muslims. May God grant these prayers, and help the ʿAlawī sayyids and all Muslims, and settle their affairs; may He revivify the signs of religion and the traces of the law of the Lord Messenger, and make the successors follow their pious predecessors, purely for the sake of God. And this through the intercession of the Great Prophet and all the Folk of This Noble Presencing.

At this point, the manual instructs the visitor to gather together his supplications, seek forgiveness, and direct the prayers for the dead. So ends the first station. The manual then moves on to the other stations of the visit, stopping at the graves of those named in the first and second Fātiḥas. A summary of the itinerary has been given in the earlier discussion on the poetic structure of the visit. It remains to note that the manual does not encompass the entire necropolis of Tarim. Only the cemeteries of the sayyids and shaykhs, Zanbal and al-Furayṭ, are visited in the liturgy. The other social categories—tribals and townsmen who are neither sayyids nor shaykhs—are left out of the manual. Their families visit them at the conclusion of the visit prescribed in it. The pedagogical and votive aims of the visit mean that only those who are thought to confer benefit, whose presence counts, are sought out. These are persons who have significance in the view of Hadrami history embedded within the manual.

Despite all that it contains, the manual for visiting the graves of Tarim is a compact volume of a mere forty-five hundred words, approximately. As liturgy, it serves as a mnemonic, an aid to ambulating recitation rather than a text to be studied indoors while sitting still; thus, it is small and portable.10 Its parsimony belies the richness of its content, which is evoked but not explicated. For that purpose, it relies on other books of reference, which provide exhaustive and detailed elucidation. The manual cites these references by invoking their authors. Al-Khaṭīb, the author of the Transparent Essence, for example, is recalled among other al-Khaṭībs, at two stations, as “ʿAbd al-Rahman b. Muhammad, Author of the Essence” Other authors receive mention among their kinsmen and associates. For bibliophiles, within the manual is found a genealogy not only of persons but one of texts as well. In the murmur of citation within recitation, the manual signals its membership within a wider historiographical tradition of Hadrami literature, which encompasses distinct genres of biography, hagiography, chronicle, genealogy, and law. In part II of this book, “Genealogical Travel,” we have seen something of how these genres combined to form a distinct, hybrid canon that took shape in the movement of a specific, Hadrami diaspora. Yet these genres are general in Arabic/Islamic literature and partake of broader Islamic discourses from which they were never isolated. The specifics of Hadrami lineages and places are always suffused with the more general history and imagery of Islam, and thus retain a vital openness. How the specific and the general coexist in any situation is never obvious but can at moments be perceived if one looks closely or listens carefully.

A Light Like Rain: Graves of Tarim, Gardens of Paradise, Genealogies of Diaspora

In ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Khaṭīb's fifteenth-century Garden of Heart Essences/Transparent Essence is an account by a sayyid, ʿAbd Allāh b. Aḥmad b. Abī ʿAlawī, who said:

The account connects with another story widely recounted in Tarim, which has the prophet Muḥammad's cousin and son-in-law, ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib, asking a man if he was from Hadramawt. When the man replied in the affirmative, ʿAlī said, “In it is the Red Hill.” This hill is identified by Hadramis as al-Furayṭ, which overlooks the graveyard of the shaykhs by that name. ʿAlī holds a special position among Yemenis, for he was sent to Yemen by the Prophet to claim their allegiance for the new religion of Islam (Ibn Hishām 1955: 649). ʿAlī is also the progenitor of all the descendants of the prophet Muḥammad, through his marriage to the Prophet's daughter Fāṭima; the Prophet had no surviving male issue. These accounts bring an otherwise obscure corner of the Arabian Peninsula within the sweep of Prophetic history and allow its participation in the cosmic events of Mecca-Medina. They make of the hill of al-Furayṭ in Tarim a relic of that history. When wealthy Hadramis die abroad in East Africa, they leave a provision in their wills for importing a tombstone carved from a bit of this hill, with its unmistakable red coloring, from Tarim and erecting it over their graves. In death they will reside under this tombstone and hope that “under it is one of the gardens of Paradise.”

In al-Khaṭīb's Garden is a subsequent account, by a shaykh, Muḥammad b. ʿAlī al-Zubaydī, of what he saw at the graves of Tarim:

When I returned from the pilgrimage to Mecca, I came to Tarim to visit its pious ones. So I entered the graveyard of the ʿAlawīs at the time of the Sacrifice. When I was upon it, I saw a light which appeared like rain, descending upon al-Furayṭ, then encircling the graves, and finally encompassing the town.

This image condenses a number of the elements that are brought together in the visit to the graves. Although the graves can be visited at any time, the formal annual visit takes place on the fourteenth of the month of Shaʿbān. This day is two weeks after the twenty-seventh of Rajab, which is celebrated as the day the Prophet made his night journey to Jerusalem and ascended the seven heavens. It also follows immediately upon the return of pilgrims from the annual pilgrimage to the tomb of the prophet Hūd. The people to whom Hūd had been sent did not heed his message, so God sent down great winds which destroyed them (Qurʾan 11, Hūd). Two weeks later, the fasting month of Ramafān begins, when God first sent down the revelations to His messenger Muḥammad. The organized visit to the graveyards of Tarim thus takes place in a period of intense interaction between sky and earth. Poised between the two, the rituals of this month engage associations already present in Islamic discourse, and draw them together in a directed narrative that is locally performed. As a Semitic religion, Islam is the “sky religion” (al-dīn al-samāwī); “Semitic” is a cognate of the Arabic samāwī, an adjectival derivative of “sky.” Its religious law, the sharīʿa, has etymological roots with the sense of “road (leading to water)” (Chittick 1994:129). Believers who observe its precepts have the chance to reside eternally in paradise, which is described as a garden.

The element that connects the images of sky, water, and garden is rain. In the southern Arabian Peninsula, rain is indisputably the direct, visible source of the flood and well waters on which agriculture depends. If it comes, it is borne on the monsoon winds blowing inland from the Indian Ocean, some time in the summer. The rains embody and are apprehended as a direct, vertical, linear relation between sky and earth. As a flood in the wadi bed, rain expresses its power in the directed linearity of the flow, which washes away everything in its path. It is for rain that Hadramis hold prayers during the pilgrimage to Hūd's tomb.13 It is also for rain that they hold their prayers by the graveyards of Tarim, beside the main watercourse. Such activities at the sites of tombs activate relations between elements that are nascent in the discursive imagery of Islam.14 The first biographical anthology of Hadrami sayyids, The Blaze (alGhurar, in reference to the white forehead of a horse), by the sayyid Muḥammad b. ʿAlī Kharid (1985:104), quotes a poem that puts the matter succinctly:

Within al-Furayṭ, Zanbal, Akdar and the watercourseInnumerable are they—sufi, saint and jurist—precepting the waterway15

The word I have translated as “precepting” is sh-rʿ, a root verb whose derivations mean both “to legislate” and “to irrigate,” with a more abstract, underlying sense of “to direct.” The poem suggests that the Sufis, saints, and jurists buried in the cemeteries of al-Furayṭ, Zanbal, and Akdar have the power to make water flow in the waterway. This power is that of the rainmaker. Who is the rainmaker? Al-Khaṭīb's Garden suggests the answer in a number of ways. The rain falls on al-Furayṭ, which is the location of the cemetery of the shaykhs, above one of the gardens of paradise; the shaykhs were already there when the sayyids arrived in Tarim. It is the shaykhs who draw water from the sky and circulate it around the town. The person who perceived the light as rain falling on al-Furayṭ is a shaykh.

Yet the imagery of light, and of Abrahamic sacrifice linked to Jerusalem and Mecca, has everything to do with the prophets and their descendants (Combs-Schilling 1989; Rubin 1975; Schimmel 1985). The prophet Muḥammad's father, ʿAbd Allāh, underwent a trial in which he was almost killed in sacrifice by his father; immediately after ʿAbd Allāh's death was averted, he married the Prophet's mother, Amina, who conceived the Prophet. The earliest Prophetic biographies contain reports of women who propositioned ʿAbd Allāh before he consummated his union with Amina (al-Ṭabarī 1988; Ibn Hishām 1955: 69). He refused them, but after lying with Amina, returned to them to take up their offers. They rejected him, because he no longer had the light he previously possessed: Amina had taken it away. One of these women, another of his wives, explained that “when he passed her he had between his eyes something like the white blaze on a horse's forehead, that she invited him in the hope that he would lie with her, but that he refused and went in to Amina bt. Wahb and lay with her, as a result of which she conceived the Messenger of God” (al-Ṭabarī 1988: 6). The imagery of light, and its association with the prophet Muḥammad, underwent extensive doctrinal elaboration at the hands of mystical thinkers such as Ibn al-ʿArabī, and it shows up in the titles of Hadrami books, such as Kharid's The Blaze, and in the white gowns, turbans, and tombs of descendants of the Prophet. On the axis that joins Prophetic seed and Light turns the renaming of al-Khaṭīb's book. The title he chose named effects and loci (garden, apothecary), while the title it was eventually given named causes and sources (the transparent essence, the grace of the sayyids of Tarim).16 In the image recounted by al-Zubaydī above, of light falling like rain, cause and effect are united.

The unification was achieved by the interpolation of Prophetic genealogy. The ability to bring rain and to divine water for wells is a persistent theme in sayyid hagiography. It is especially prominent in accounts of sayyids moving away from Tarim in the Arabian Peninsula, either to found new settlements on the frontiers of religion or to make pilgrimages. The most famous and probably earliest instance is that of ʿAbd Allāh Bā ʿAlawī (d. 1331). He lived before the convergence of streams that created the ʿAlawī Way in the fifteenth century and is not known for rituals, special places, or written works. His hagiography is replete instead with the operations of grace as events. He visited Mecca twice and both times brought rain to the parched town, conducting the prayers for rain (al-Khaṭīb n.d.; al-Shillī 1982: 403 ʿ.; Bā Wazīr 1961). Sayyid founders of settlements in Mashhad and Sayʾūn in later centuries divined wells where they settled (al-ʿAṭṭās n.d.; al-Kindī 1991).

In the emergence of the ʿAlawī Way from the fifteenth century on, Prophetic genealogy came to provide a master narrative that brought together previously independent domains of ritual, place, and text. These domains combined to form an institutional complex that, while inseparable from the descendants of the Prophet, enabled participation by others. To borrow Peter Brown's terms, persons like Aḥmad al-Junayd were “impresarios” who “coined a public language” of the saints that developed and persisted over centuries (Brown 1981: 48–49). In this language, lexical elements such as sky, rain, grave, water, irrigation, law, learning, and cure were brought into syntagmatic relation in the chain-linking of genealogy. Genealogy enabled performative texts such as Aḥmad al-Junayd's manual for visiting the graves of Tarim to activate the necropolis of the cemetery, opening it up to commerce with the living and engagement with history. With his Salve for the Sickly, visitors exchange visits, greetings, and votive requests with the dead, and in doing so, they relate to the dead as interlocutors with whom they interact in the same space and time: one does not simply go to the graveyards of Tarim; one goes to meet specific persons. In geographical and genealogical space, ancestors, the prophets Hūd and Muḥammad, and their descendants are not strangers but locals and intimates. In focusing his attention on them, al-Junayd was able to avoid the outside world, whose mediating circuits he was so suspicious of. Instead, value and blessings are obtained right at home, along the straight and narrow of religious rectitude and lineal descent. Intercession by the saints does not constitute mediation in the fraught ways we discussed in chapter, “A Resolute Localism.” They simply make accessible divine grace, which flows downward like rain.

Even so, the linearity of the genealogies and the inexorability of their emanation are more apparent than real. The genealogies do not live in timeless self-sufficiency; they are products of and subject to histories in which their discursive forms and human contents change considerably. The first two Fātiḥas of al-Junayd's Salve give us an idea of the content of these histories. Between al-Khaṭīb's fifteenth-century Garden/Apothecary/Essence and al-Junayd's nineteenth-century Salve/Gift are four centuries and as many countries. In this time, the concepts, representations, and human content of the genealogies underwent tremendous development. In al-Khaṭīb's Garden, genealogy made a modest and circumscribed showing, appearing mostly as part of a person's name, or as acknowledgment of a general precedence accorded Prophetic descent. The interest of the book was that of the enthusiast; it lay in savoring the particulars of each story of the saints rather than in an overarching narrative structure. The book strictly organized the stories, as a sequence of numbers, not the persons. Persons were simply lumped into gross groups, generations. The ratio of four generations to five hundred stories indicates the relative emphasis. In contrast, by the time al-Junayd's Salve was written and copied, genealogy had become an elaborate and specialized knowledge, which could organize hundreds of names in a compact manual. Its maturity as a science allowed Aḥmad al-Junayd to wield it with economy and precision.

Historical development is not everything. Location too is important. Unlike the diasporic texts, which came to concentrate on the sayyids, or on their relations with non-Hadrami nobility abroad, al-Junayd's manual represents a broader profile of Hadrami society in Hadramawt. It was written for Tarim and for the various categories of persons living in it. In the conduct of their lives, disparate groups of people had plenty to do with each other. Thus, while the manual amply represents the lineal genealogies, it also engraves lateral exchanges between unrelated categories of persons, and enacts these exchanges in the visit. In return to Tarim as pilgrimage, the homeland expands from being a pure point of sayyidly origin to a diverse one of many families with different histories and other beginnings. Prophetic precedence in the pilgrimage does not so much exclude others as lead and gather all. The point was to get along, to have hearts that were clean and wadis that were watered. That was the point of collective prayers at the cemetery, beside the flood path, the prayers for rain.

The license is an ijāza.

This line—“Lā ilāha illā Allāh”—is part of the Muslim declaration of faith.

Rivalry between the al-ʿAmūdīs and the sayyids is a theme that runs through Hadrami history until the twentieth century. The issue goes beyond the scope of this book, but a skeletal account would include al-ʿAmūdī's alliance with the northern Qāsimī imams in the eighteenth centuryand with Irshādīs in the twentieth.

On ḥaḍra, see chapter.

These prayers are referred to as the “five obligations,” khamsa furūḍ. The practice is not based on the primary sources of Islamic law, and a parallel is drawn to the Prophet's extra-Qurʾanic pronouncements (ḥadīth) by naming the practice Sunnat al Walī, or Tradition of the Saint.

The difference between vocalized recitation (qirāʾa) and silent reading (iṭṭilāʿ) in Islamic literary culture is significant; Messick (1993) treats the topic theoretically and ethnographically. Comparative and historical studies attest to the vitality—even primacy—of orality within traditions that seem to be dominated by texts (Graham 1987; Svenbro 1993).

In the hagiography of Prophet Muḥammad, the learned Christian monk Baḥīrā, whom the Meccans encounter on a trading expedition to Syria led by ʿAlī's father, Abū Ṭālib, authenticates the prophethood of Muḥammad. Baḥīrā recognizes the seal of prophethood between Muḥammad's shoulders, as well as other features that correspond to descriptions in his book, a repository of knowledge handed down through generations of monks who lived in his cell (al-Ṭabarī 1988: 44–46).

The question of whether rain descends on the tombs of prophets is much discussed in the polemical literature. Ibn Taymiyya recounts that ʿAʾisha, Prophet Muḥammad's favorite wife, once exposed his grave so that rain might fall, but to no avail, even though God's mercy does descend upon his grave, in Ibn Taymiyya's opinion (Ibn Taymiyya 1998:197).

For example, in the chapter “The Heights” (al-Aʿrāf) of the Qurʾan, the following line appears eight lines before mention of the prophets Hūd and Ṣāliḥ, who are associated with Hadramawt: “It is He Who sendeth the Winds like heralds of glad tidings, going before His Mercy: when they have carried the heavy-laden clouds, We drive them to a land that is dead, make rain to descend thereon, and produce every kind of harvest therewith, thus shall We raise up the dead: perchance ye may remember (Qurʾan 7:57, Abdullah Yusuf Ali's translation). Etymologically, the name of Hadramawt is sometimes derived from ḥaḍara mawt, making it a land in which “death was present.”

Al-Khaṭīb chose the title Garden of the Heart Essences, Apothecary for Incurable Maladies. Later the book was retitled The Transparent Essence, Recounting the Marvels of the Sayyids of Tarim, and Their Contemporaries in It of the Greatest, Gnostic Saints.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| October 2022 | 2 |

| December 2022 | 1 |

| April 2023 | 5 |

| November 2023 | 1 |

| August 2024 | 2 |

| October 2024 | 7 |