-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Damian M Herz, Michael J Frank, Huiling Tan, Sergiu Groppa, Subthalamic control of impulsive actions: insights from deep brain stimulation in Parkinson’s disease, Brain, Volume 147, Issue 11, November 2024, Pages 3651–3664, https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awae184

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Control of actions allows adaptive, goal-directed behaviour. The basal ganglia, including the subthalamic nucleus, are thought to play a central role in dynamically controlling actions through recurrent negative feedback loops with the cerebral cortex. Here, we summarize recent translational studies that used deep brain stimulation to record neural activity from and apply electrical stimulation to the subthalamic nucleus in people with Parkinson’s disease.

These studies have elucidated spatial, spectral and temporal features of the neural mechanisms underlying the controlled delay of actions in cortico-subthalamic networks and demonstrated their causal effects on behaviour in distinct processing windows. While these mechanisms have been conceptualized as control signals for suppressing impulsive response tendencies in conflict tasks and as decision threshold adjustments in value-based and perceptual decisions, we propose a common framework linking decision-making, cognition and movement. Within this framework, subthalamic deep brain stimulation can lead to suboptimal choices by reducing the time that patients take for deliberation before committing to an action. However, clinical studies have consistently shown that the occurrence of impulse control disorders is reduced, not increased, after subthalamic deep brain stimulation surgery. This apparent contradiction can be reconciled when recognizing the multifaceted nature of impulsivity, its underlying mechanisms and modulation by treatment. While subthalamic deep brain stimulation renders patients susceptible to making decisions without proper forethought, this can be disentangled from effects related to dopamine comprising sensitivity to benefits versus costs, reward delay aversion and learning from outcomes.

Alterations in these dopamine-mediated mechanisms are thought to underlie the development of impulse control disorders and can be relatively spared with reduced dopaminergic medication after subthalamic deep brain stimulation. Together, results from studies using deep brain stimulation as an experimental tool have improved our understanding of action control in the human brain and have important implications for treatment of patients with neurological disorders.

Introduction

Movements enable us to interact with our environment. Rather than simply predicting whatever happens next, we can adapt our behaviour to reach our goals and avoid harm.1 But how do we make sure that our actions are in line with our goals? Cognitive control refers to a set of functions in the brain that monitor our environment and behaviour, and implement changes of our actions when warranted.2,3 One of the main objectives of cognitive control is to enable goal-directed behaviour. In contrast to automatic or habitual behaviour, in which a certain stimulus or state maps directly to an action, goal-directed behaviour, reflects an effortful process allowing more flexibility, e.g. when the value of an outcome or action-outcome contingencies have changed.4-6 Thus, in some circumstances, we need to suppress automatic, fast responses to select our actions based on slower cognitive processes (Fig. 1A). This is thought to be implemented by cognitive control facilitating the allocation of resources such as attention and working memory to our actions when necessary.3,7,8

![Conceptual framework and experimental model. (A) Goal-directed behaviour (purple) relies on assigning expected outcomes to actions, which can then be chosen based on optimization of subjective value. In contrast, in habitual or automatic behaviour (yellow), a certain state or stimulus directly maps to an action. This direct mapping is thought to be faster and less computationally costly compared to goal-directed behaviour. (B) In sequential sampling models, evidence (grey) for one option versus another is accumulated over time until it reaches the decision threshold a (horizontal black line). With low thresholds (dashed horizontal lines), the option is chosen quicker but is more likely to be incorrect (here choice B in yellow), while higher thresholds (continuous horizontal lines) lead to more accurate but slower choices (here choice A in purple). Parameters t and v refer to, respectively, non-decision time (e.g. early sensory processing) and drift rate (rate of evidence accumulation). (C) A simplified illustration of cortical-subthalamic nucleus (STN) connectivity shows that cortical organization (purple to white gradient) is also reflected in STN and basal ganglia output structures [internal pallidum (GPi) and substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr)] but with considerable overlap. There is a tremendous dimensionality reduction from cortex to STN, which has a net neural inhibitory effect on cortex and descending output. (D) Illustration of a deep brain stimulation (DBS) lead, which can be used for recording activity from and apply stimulation to the STN. LFP = local field potential.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/brain/147/11/10.1093_brain_awae184/1/m_awae184f1.jpeg?Expires=1750196598&Signature=CrhIU2O~TMuF8jdwl0sMqYmE2dmgd~zps-TBp7SEkOaGmS4QSLPDPE8qjclSgCfrwV03UjdRkIwCVP5zonjad8YtdvDmMqUuEEJGXeyI~FHlpzxDzskDcejlV2wPrCUcJX6N3qNfDTl7S5U8vNkCcrHdZdhTSOEWMa-YFuK7lgSWhlXcLvCNjg2zE5ww~805EeuJZ5H2d8dXbQ9V~wz~vTUFkrbXeOHeTQM8k9czNUZqj5CCWvG--2AReGfhowyO2jFqOSog~LhT2pcq8nEerlWQ5whF7zeU~5Fgl~VBxs0yBjUbjx1PPP58HnqMwKT87Jcpn1KiAIpWa1GksY5uWA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Conceptual framework and experimental model. (A) Goal-directed behaviour (purple) relies on assigning expected outcomes to actions, which can then be chosen based on optimization of subjective value. In contrast, in habitual or automatic behaviour (yellow), a certain state or stimulus directly maps to an action. This direct mapping is thought to be faster and less computationally costly compared to goal-directed behaviour. (B) In sequential sampling models, evidence (grey) for one option versus another is accumulated over time until it reaches the decision threshold a (horizontal black line). With low thresholds (dashed horizontal lines), the option is chosen quicker but is more likely to be incorrect (here choice B in yellow), while higher thresholds (continuous horizontal lines) lead to more accurate but slower choices (here choice A in purple). Parameters t and v refer to, respectively, non-decision time (e.g. early sensory processing) and drift rate (rate of evidence accumulation). (C) A simplified illustration of cortical-subthalamic nucleus (STN) connectivity shows that cortical organization (purple to white gradient) is also reflected in STN and basal ganglia output structures [internal pallidum (GPi) and substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr)] but with considerable overlap. There is a tremendous dimensionality reduction from cortex to STN, which has a net neural inhibitory effect on cortex and descending output. (D) Illustration of a deep brain stimulation (DBS) lead, which can be used for recording activity from and apply stimulation to the STN. LFP = local field potential.

A similar process determining whether we should act fast or slow is studied in the field of decision-making. Decision-making is concerned with the computations involved in comparing two or more options, e.g. regarding their expected value in value-based decision-making or sensory properties in perceptual decision-making.9-11 Weighing the time we spend on deliberation (speed) versus the likelihood of arriving at the correct choice (accuracy) is central for optimizing decisions.12,13 Mathematically, this can be conceptualized as an increased level of evidence that needs to be accumulated before an action is selected, often referred to as ‘decision threshold’ in sequential sampling models.14,15 The decision threshold can be elevated when faced with conflicting information, increased task difficulty or after a mistake16-20 (Fig. 1B). Such dynamic adjustments of decision thresholds are similar to cognitive control in that they allow people to switch to more cautious ways of selecting their actions when necessary, while routinely relying on simpler decisions requiring less evidence or even selecting actions without assigning any explicit value computations.5,21-23

Thus, the ability to control fast but putatively suboptimal actions to allow slower, more accurate choices is a crucial process for optimizing behaviour. Traditionally, cognitive control and decision-making have been studied in separate fields, the former focusing mainly on peoples’ abilities to override automatic responses for allowing deliberate choices, and the latter primarily studying the benefits and costs of different options. However, there is mounting evidence for a large overlap between the involved mechanisms.24 In particular, both critically rely on optimizing the time we take before committing to a choice, which can be parsimoniously conceptualized as the controlled delay of an action. How might this process be implemented in the brain?

The basal ganglia (BG) consist of a network of nuclei seated deep in the brain common to all vertebrates.25 The BG receive high dimensional somatotopic afferents from cortical neurons (primarily layer 5) and send low dimensional feedback to the cortex in a recurrent negative feedback architecture, which also exists at the subcortical level.26-29 Cortico-BG loops originating from different cortical areas are organized in parallel but overlapping circuits showing a cortical rostro-caudal gradient,30,31 illustrated in Fig. 1C. The glutamatergic subthalamic nucleus (STN) receives input from D2-expressing GABAergic neurons of the striatum relayed via GABAergic prototypic neurons of the external pallidum in the indirect pathway and monosynaptic glutamatergic input from cortex in the hyperdirect pathway, as well as afferents from multiple subcortical areas.32,33 Both the indirect and hyperdirect pathways exert a net inhibitory effect on their output structures.25,27 Given the immense dimensionality reduction (roughly a 1000-fold reduction in the number of neurons from striatal BG input to BG output26,34), the very fast monosynaptic connection between cortex and STN, as well as the net inhibitory effects of subthalamic activation, the STN has been proposed to mediate fast and broad inhibition of neural activity resulting in a pause of behaviour.13,16,35-38

At the cortical level, several areas of the prefrontal cortex, in particular (pre)-supplementary motor area, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex and right inferior frontal gyrus are thought to be neural hubs evaluating information such as the presence of conflict, unexpected events or negative feedback to recruit the necessary control mechanisms.3,6,16,39,40 Importantly, the prefrontal cortex has direct connections to the STN through the hyperdirect pathway innervating the STN just ventro-medially to and overlapping with subthalamic regions mainly connected to motor cortical areas.31,41-43 Thus, the architecture of cortico-STN networks seems well suited to implement the controlled pause or delay of an action, which has been supported by evidence in non-human primates.44,45 This allows the avoidance of fast but putatively suboptimal actions for slower, more accurate choices.46,47 However, this hypothesis is difficult to test in humans, since the deep-seated localization and small size of the STN make it notoriously difficult to record activity from the STN or interfere with its function non-invasively. This challenge can be overcome by studying patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) who are treated with STN deep brain stimulation (DBS) for clinical purposes.

PD is a frequent, disabling neurological disorder characterized by progressive degeneration of multiple neuromodulatory systems, in particular dopaminergic cells in the midbrain.48 PD can lead to various neuropsychiatric symptoms.49 It is defined clinically by the hallmark presence of movement slowness (bradykinesia), as well as other motor symptoms such as shaking (tremor) and increased muscle stiffness (rigidity).49,50 The mainstay treatment of PD is dopamine replacement. In case of complications to medical treatment, e.g. movement fluctuations and involuntary movements (dyskinesias), or insufficient effects on tremor, symptoms can be alleviated by DBS.51 During DBS surgery, electrodes are implanted in subcortical structures, in PD most commonly the STN, and connected to a subcutaneous implantable pulse generator (IPG). For symptom alleviation, stimulation is given continuously at high frequencies (>100 Hz) at intensities of several mA, depending on the target structure and the clinical response to DBS. The mechanisms of DBS are multifaceted at different temporal and spatial scales.51-54 Functionally, the effects of STN-DBS are in line with a reduced excitatory influence of cortical and increased inhibitory influence of subcortical areas on the STN, which has been described as a functional or informational lesion.53,55

Besides its important role in clinical therapy, DBS can also be used as an experimental tool to better understand how the brain mediates behaviour.56-59 In some DBS centres, surgery is performed in two stages, where electrodes are implanted and externalized in the first stage and only connected to the IPG (i.e. internalized) in the second stage ∼1 week after the first operation.51 This allows the recording of local field potentials (LFPs) from the STN or application of electrical stimulation through the externalized extension cables before internalization of the device (Fig. 1D). Novel DBS devices allow simultaneous stimulation and recordings of STN LFPs in patients with implanted IPGs without the need for electrode externalizations.51

Invasive STN recordings have revealed pathological activity patterns in PD underlying movement slowness60,61 and therapy-related involuntary dyskinesia movement.62,63 However, they can also be used to infer physiological STN functions in controlling behaviour. Of note, when inferring physiological functions of the STN, it is important to consider that the studied participants are not healthy but suffer from a neurological disorder. To address this, most DBS studies discussed here tested PD patients ON their dopaminergic medication, which is thought to normalize neural activity and behaviour as much as possible. However, since dopamine medication can in itself lead to abnormal behaviour,64,65 it is helpful to include a healthy control group for behavioural testing and to conduct complementary neurophysiological studies in healthy non-human animals or humans suffering from other disorders, which can be treated by DBS surgery, such as obsessive compulsive disorders. Thus, taking these considerations into account, DBS gives the unique opportunity to record neurophysiological activity in humans from the STN that cannot easily be recorded non-invasively and to modify brain activity and behaviour through temporally and spatially focused electrical STN stimulation. In this review, we will first consider previous studies recording neural activity from the STN during tasks probing cognitive control and decision-making, before summarizing the behavioural effects of STN DBS and finally discussing clinical implications.

Recording neural activity through deep brain stimulation electrodes

Invasive STN recordings during behavioural tasks using externalized DBS leads have been conducted for over 20 years.60 The strongest task-modulated LFP signal is the beta band (∼13–30 Hz), which, similar to motor cortical beta power, is reduced just prior to and during movement as well as after salient cues and increases after movement termination. This is often termed beta event-related desynchronization (ERD) and synchronization (ERS), respectively. Furthermore, increases in low frequency activity around the theta band (∼2–8 Hz; the theta band is usually defined as 4–8 Hz in EEG but can extend to even lower frequencies at ∼2 Hz in the STN) are often seen after cues and around movement, similar to frontal cortical theta power. Finally, there are strong increases in broad-band gamma activity (∼50–90 Hz) at movement onset (for an example see Fig. 2A and B). These general task-related changes in the LFP are highly reproducible and have been reported throughout a range of different tasks.66-72 Task-related changes in these frequency bands can be used as a correlative measure to examine whether modulations of spectral STN activity correspond to a given (observable or latent) process of interest.

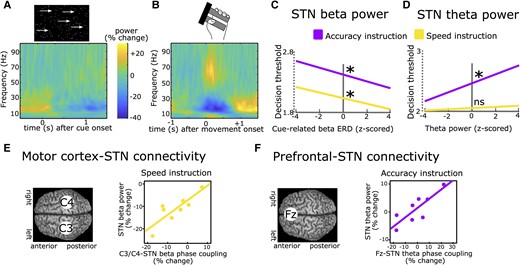

Recordings of subthalamic activity. (A) Time-frequency spectrum of subthalamic nucleus (STN) recordings (group-level) aligned to the onset of a moving dots-cue. (B) Same as in A but aligned to onset of movement (force grip). (C) Stronger cue-induced reductions in STN beta power are predictive of lower decision thresholds irrespective of instructions. (D) Increases in STN theta power during deliberation are predictive of higher decision thresholds after Accuracy (purple) but not Speed instructions (yellow). (E) Phase coupling between electrode C3/C4 (covering motor cortex) and STN in the beta band correlates with STN beta power during Speed (yellow) but not Accuracy instructions (not shown). (F) Phase coupling between electrode Fz (covering medial prefrontal cortex) and STN in the theta band correlates with STN theta power during Accuracy (purple) but not Speed instructions (not shown). A and B are based on Herz et al.73C–F are based on Herz et al.69

There is mounting evidence that dynamic modulation of STN theta and beta activity are reflective of processes related to suppressing and delaying actions. These modulations can be observed in studies of cognitive control and decision-making and can be related to behavioural adjustments at the single trial level. Yet, there are important distinctions between subthalamic control of actions in the theta and beta band, particularly regarding their modulation by task context, which we will discuss in more detail below.

In an early study,74 patients had to push a button with their right or left hand after an imperative cue. The direction (right versus left) was indicated by a preceding warning cue. In 20% of trials, the imperative cue was replaced by another cue signalling that participants had to refrain from executing the movement. In all conditions, beta power was reduced after each cue, but this decrease was terminated earlier in trials requiring movement suppression leading to a relative increase of beta power. Furthermore, inter-individual differences in the latency of the cue-related beta ERD were correlated with differences in mean reaction times. The relative increase in STN beta power in trials with movement inhibition versus execution was confirmed in several other studies.75-80 These findings were mainly interpreted as STN beta ERD allowing movement execution, which could be aborted by a relative increase in STN beta power. However, the relative difference between conditions might have simply reflected the absence of a movement-related beta decrease in conditions with movement inhibition since STN beta power is strongly reduced during movements (as shown in Fig. 2B). Furthermore, since no action is executed during movement suppression, it is difficult to relate modulations of STN beta power to trial-by-trial changes in behaviour. One way to address this is to induce a longer deliberation period between imperative cue and movement (and thus between the cue-related and movement-related beta ERD) and to use computational modelling to reveal latent cognitive mechanisms. In a recent study, participants performed a moving-dots task81 (Box 1) in which they had to decide whether a cloud of dots appeared to move to the left or to the right and then press a button with the corresponding hand.69 When patients were instructed to weigh accuracy over speed, they had increased reaction times and committed fewer fast errors. Computational modelling using a drift diffusion model15 revealed that this could be explained by an increase in the decision threshold. STN beta power showed a marked reduction after the moving dots cue, which was steeper in the Speed condition favouring fast over accurate choices. The steeper beta was reduced on a trial-by-trial basis, the faster were reaction times and the lower were decision thresholds (Fig. 2C). Importantly, responses occurred much later (∼1 s) on average than the duration of the cue-induced beta ERD and the relationship between STN beta power and, respectively, reaction times and decision thresholds was preserved when excluding any trials where responses fell into the beta ERD window. Thus, the relatively higher beta power in trials with increased decision thresholds could not simply be explained by movements already occurring in this time period when decision thresholds were low. This finding has since been replicated twice.17,73 Furthermore, it was demonstrated that decision thresholds were specifically reflected by modulations of the cue-induced beta ERD, while the later occurring movement-related beta ERD correlated with movement, not decision, speed.73

Eriksen-Flanker task: The correct response is indicated by a central arrow, which is flanked by distracting arrows. In incongruent trials the central arrow points to a different direction compared to the flanking arrows. Different versions of the task exist using letters or numbers.

Moving dots task: A cloud which consists of many white dots is shown on a screen. While some dots move coherently to one direction (e.g. 8% of all dots in more difficult trials or 50% of dots in easier trials) the remaining dots move randomly. Participants have to decide whether the cloud appears to move to the left or right and indicate this choice usually by a left- versus right-hand movement.

Simon task: The correct response is indicated by the colour of a cue (or alternatively a letter), which is presented either to the left or right of a central fixation cross. In incongruent trials, the correct response is different to the spatial position of the cue (e.g. a cue indicating a right hand response is shown on the left side of the screen).

Stop-signal reaction time task: In a subset of trials an already initiated response (indicated by a Go-cue) has to be aborted when a visual or auditory Stop-signal is presented. The delay between the Go-cue and the Stop-signal is adjusted over time in a stair-case procedure so that patients are able to successfully stop the response in 50% of trials. The stop signal reaction time can then be computed by subtracting the mean stop signal delay from the mean reaction time.

Stroop task: The names of colours are written in incongruent ink colours. Participants have to state aloud the ink colours ignoring the written words (e.g. if the word ‘red’ is written in yellow ink the correct response is ‘yellow’).

In tasks with conflicting information, such as the Eriksen-Flanker task82 (Box 1), a strong, short-lasting cue-induced theta power increase can be observed in the STN and over medial prefrontal cortex in EEG.38,72,83-85 An increase in STN theta power can also be detected during deliberation in the moving dots task even if there is no clear cue onset.18,86 Similar to STN beta activity, STN theta power has consistently been shown to correlate with single-trial adjustments in decision thresholds.18,69,73,86 However, unlike STN beta power, this relationship is dependent on task context. Increases in STN theta activity only correlate with increased decision thresholds when participants are more cautious, weighing accuracy over speed18,69,73,86 (Fig. 2D). Relatedly, the experience of decision conflict—signalling the need for further evidence accumulation to arrive at an accurate decision—is related to increases in cortical and STN theta activity.38,83,86,87 These patterns are similarly observed in healthy humans in simultaneous functional MRI (fMRI) and EEG studies linking conflict-induced increases in midfrontal cortical theta in EEG to STN signals in fMRI and decision threshold adjustments.88 Thus, beyond their spectral properties, STN theta and beta oscillations also seem to differ regarding their modulation by task context and strategy.

What might be the role of the recorded task-related LFP modulations in the STN? LFPs reflect a summation of various underlying neural processes including synaptic transmembrane currents, calcium flux and action potentials from thousands of neurons in proximity of the recording electrode.89 Thus, LFP recordings can reveal synchronized, oscillatory neural population activity. A prominent theory proposes that such neural oscillations provide a ‘window in time’ where neural communication between spatially distinct brain regions can take place.90,91 According to this theory, the effect of action potentials on their target neurons depends on the phase of ongoing oscillations so that neurons which are aligned regarding their phases can communicate more efficiently compared to neurons that are out of sync. Several studies have demonstrated that spiking activity in the STN is aligned to the phase of theta and beta oscillations.92-95 In the study described above,69 during the moving dots task, activity changes in the beta band were predominantly observed over motor cortical areas, and in the theta band over midline prefrontal cortex (cortical signals were measured using EEG), in line with previous studies18,83,86,88,96,97 (Fig. 2E and F). However, beta oscillations are also expressed in prefrontal cortex98-101 and theta oscillations in motor cortical areas,102,103 arguing against a clear-cut distinction in regionally specific cortico-STN communication according to distinct frequency bands. Nevertheless, oscillatory communication might facilitate adapting which cortical areas primarily impose activity changes in the STN to mediate action control in specific time windows. For beta activity, it has been demonstrated that increased beta power at the cortical level is locked to increased beta activity at arm muscles during static contractions, which is attenuated during phasic movements.104,105 Thus, this neural signal could facilitate stabilization of the current posture for delaying dynamic movement.106 One challenge for this hypothesis is that oscillatory synchronization might be too slow to implement a quick action pause, at least for lower frequencies in the theta and beta band during outright stopping.107 Stopping-related single neuron activity in (primarily ventro-medial) STN occur well before any oscillatory beta increases.42 Thus, there is strong correlative evidence for a role of STN theta and beta oscillations in delaying actions, but does the STN have causal behavioural effects in humans? One possibility for testing this is to apply electrical stimulation to the STN using DBS and measure the resulting changes in behaviour.

Shaping behaviour with deep brain stimulation

Building on results from rodent studies implicating STN in cognitive control,108,109 early evidence that STN DBS might impair functions related to cognitive control in humans came from clinical assessments after DBS surgery showing that DBS worsens performance of the Stroop task110 (Box 1), which is often part of the standard neuropsychological evaluation.57,111-113 A shortcoming of such clinical neuropsychological assessments is that often only a summary statistic is reported, e.g. the difference in reaction times in trials with versus without conflict, accuracy rates or similar. However, the proposed computational role of the STN makes a much clearer prediction. STN DBS should lead to an increase in particularly fast erroneous responses slipping through control during response conflict, while this should not be the case if responses have been slowed down.44,45,47 Three separate studies tested PD patients during a Simon task114 (Box 1) on and off DBS and analysed accuracy rates as a function of reaction times. Two of these studies found that indeed STN DBS significantly increased error rates in the fastest, but not in slower, conflict trials,115,116 while the third study found a similar, albeit not significant effect, putatively due to a lower sample size.117 Patients’ ability to avoid hasty choices during decision-making has been assessed in several studies on and off DBS. These studies have consistently observed that continuous high-frequency DBS impairs patients’ ability to slow down responses when caution is warranted, leading to reduced decision thresholds in both value-based and perceptual decision-making.83,118-122

There are, however, some short-comings of the approach comparing separate on versus off DBS conditions. DBS is used as a clinical treatment for PD. When patients who are chronically implanted with DBS are withdrawn from DBS treatment in one condition, their clinical state will deteriorate considerably compared to on DBS. Thus, patients are overall slower, might have tremor and experience other discomfort due to symptom exacerbation. Such more unspecific (i.e. not task-related) effects of DBS are difficult to account for in statistical designs and can introduce substantial variability. For example, for outright stopping during the stop-signal reaction time task123 (Box 1), previous studies have shown improvement,124-126 deterioration127,128 and no overall effects37,129,130 of STN DBS, despite strong evidence for causal effects of STN on outright stopping in rodent studies.131,132 This could, next to differences in exact electrode placement and methodologies,127,133-135 be due to differences in the clinical state when patients are studied on and off DBS. PD patients who express impaired response inhibition OFF treatment136 might show improved performance with DBS, while the opposite might be true for patients with preserved inhibition without treatment.130 In addition, a study showing positive effects of STN DBS on stopping in PD patients reported that this effect could also be achieved with DBS of the ventral-intermediate nucleus of the thalamus, a target for tremor-dominant PD, suggesting general DBS effects related to clinical improvement.126 A second limitation of classical on versus off DBS studies is that there can be ambiguity regarding the mechanism being affected by DBS, since stimulation is given continuously. For example, altered performance could be related to changes during deliberation, action preparation or outcome evaluation.68

To address these issues, recent studies have leveraged technical advances in DBS for applying stimulation in short bursts rather than continuously. Since the exact timing of stimulation can be varied from trial to trial, this makes any immediate changes in the clinical state of the patients unlikely (on- and off-DBS trials are compared within the same session, see later) and can facilitate inference of timing-specific effects of STN DBS on distinct processes underlying the observed behaviour.

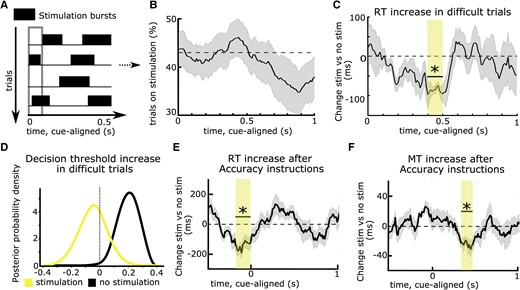

The first study assessing timing-specific effects of STN DBS on delaying actions tested PD patients who performed a moving dots task whilst STN DBS was applied in an adaptive DBS (aDBS) design.17 Recorded STN beta power triggered DBS whenever STN beta power crossed a certain threshold and was turned off again when beta power fell below this threshold,137,138 resulting in repetitive bursts of stimulation throughout the task (Fig. 3A). Importantly, this resulted in stimulation occurring in approximately half of all trials in any 100 ms window throughout the task (Fig. 3B), so that behaviour at each time window could be compared for trials where DBS had been given versus trials where no stimulation had been given. Results showed that both aDBS and continuous DBS impaired patients’ ability to slow down responses in line with previous studies.83,118-120 However, during aDBS this effect was restricted to a short ∼100 ms time window during deliberation (Fig. 3C). Stimulation during this processing window abolished the dynamic increase in decision thresholds during more difficult trials observed off DBS—and even during aDBS if stimulation was not given in this specific window (Fig. 3D). Together, this study demonstrated that STN effects on decision threshold adjustments are highly dynamic and related to short processing windows. They are also consistent with the dynamics of detailed neural circuit models of STN, in which initial brief STN activation is related to a temporary pause in action selection, implementing a collapsing decision boundary.47,139,140

Timing-specific stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus. (A) Deep brain stimulation (DBS) can be given in bursts rather than continuously, resulting in stimulation being applied in some trials, while no stimulation occurs in other trials in any given time window (in the 100 ms time window indicated by the grey rectangle, DBS was given in trials 2 and 4, while no DBS was given in trials 1 and 3 in this example). (B) Using an adaptive DBS set-up, stimulation was given on average in 43% of trials (dotted line) across time windows, which varied slightly according to fluctuation in subthalamic nucleus (STN) beta activity. (C) DBS reduced the reaction time (RT) increase in difficult trials only when given in a specific time window, 0.4–0.5 s after onset of the moving dots cue (marked by the yellow rectangle and an asterisk). (D) When DBS was given in this time window, patients no longer increased their decision thresholds during more difficult trials (yellow probability distribution with a mean close to 0), while this was preserved when DBS was not given in this exact window (black probability distribution shifted to the right from 0). The same effects were observed when comparing continuous DBS to an off DBS condition (not shown). (E) DBS impaired patients’ abilities to properly increase their RT after Accuracy instructions when given in a time window just before onset of the moving dots cue (marked by the yellow rectangle and an asterisk). (F) The same as E but for movement times (MT). Here, the significant time window showing timing-specific effects of DBS occurred later during the trial and the DBS effects on, respectively, RT and MT were not correlated. Note that in C and D, task difficulty changed on a trial-by-trial basis, while in E and F, Speed versus Accuracy instructions changed at each trial. A–D are based on Herz et al.17E and F are based on Herz et al.73

Such timing-specific effects of STN DBS have also been observed during the Stroop task.78 Since STN DBS was given in bursts throughout the experiment, the behavioural effect of DBS could not be explained by changes in the clinical state of the patients. What remained unclear, however, was whether the effect of DBS might have been related to fluctuations in STN beta activity, since aDBS was triggered by beta power, despite several control analyses to exclude this possibility.17 Furthermore, experimental factors modulating deliberation also affect how movements are performed.141,142 Could the observed effects of DBS on delaying choices be related to its effect on speeding up movement? To address these issues, a recent study modified stimulation so that the duration of DBS bursts and the interval between bursts were optimized to apply DBS on 50% of trials in any 100 ms window without this being triggered by changes in STN beta power. Patients performed a moving dots task in which, at each trial, patients were instructed to be as accurate or as fast as possible, which has been shown to significantly modulate both reaction times and movement speed.141 Movement speed was assessed by recording patients’ responses on a dynamometer. The main finding of the study was that DBS interfered with patients’ abilities to both slow down reaction times and movement speed when caution was warranted but that these effects occurred at different time points during the trial. While response times (and decision thresholds) were modulated by STN DBS just around onset of the moving dots cue (Fig. 3E), movement speed was modulated several hundred milliseconds later (Fig. 3F), and the two effects were not correlated. This demonstrated that decision and movement speed in the STN are controlled independently even if both are modified, e.g. due to time pressure. Finally, by applying stimulation bursts independently to the right versus left STN in a separate session, the study showed that STN DBS only interferes with slowing down choices when applied contralaterally to the moving hand, while ipsilateral DBS had no effects on behaviour. This finding adds to recent evidence that while cortico-STN networks can suppress behaviour broadly, i.e. beyond the task-relevant effector muscles,37,38 this effect is restricted to the contralateral body side.143,144

The two approaches described above, i.e. recording LFPs and applying stimulation through DBS electrodes, can also be combined. Using a bipolar montage surrounding the stimulation contact for common-mode rejection and appropriate artefact correction procedures, it is possible to record STN LFPs during DBS.17,68,73,145,146 Intriguingly, studies applying bursts of STN DBS and recording LFPs have consistently observed that timing-specific causal effects of DBS occur just prior to time windows where modulations of STN LFPs are reflective of this behaviour.17,68,73 For example, in the study discussed above,17 STN beta power from 500–800 ms after the moving dots cue correlated with decision threshold adjustments during difficult trials, with higher beta power being related to higher decision thresholds. Applying stimulation just prior to this time window, 400–500 ms after the cue, impaired patients ability to increase decision thresholds during difficult trials and reduced STN beta power in the time window where it usually (i.e. off DBS) was reflective of decision threshold adjustments. What could be the reason for this shift in timing between STN DBS effects and STN LFP correlates of behaviour? One possibility is that it might be necessary to suppress oscillations early on to prevent their expression, assuming a causal relationship between modulations in oscillatory STN activity and behavioural changes. In line with this, DBS reduces beta power longer than the exact duration of stimulation.68,73 Another possibility is that LFP changes are reflective of a neural process that has already taken place. For example, during outright stopping, inhibition might be achieved by modulation of fast single unit dynamics in the STN, while later occurring increases in STN beta activity might primarily maintain this state or regulate evaluative processes.42 A related possibility is that the relationship between oscillatory field activity and spiking might change with the delay after stimulus onset, as suggested by recent biophysical modelling of STN.139 Irrespective of the exact mechanism, together, these results provide strong evidence that cortico-STN circuits causally contribute to the controlled delay of action and that this dynamic process occurs in ‘critical’ time windows, which can be disturbed by DBS. This raises the question of whether STN DBS, beyond its beneficial effect on motor symptoms in PD, might also have detrimental effects rendering patients susceptible to impulsive behaviour.

Clinical implications

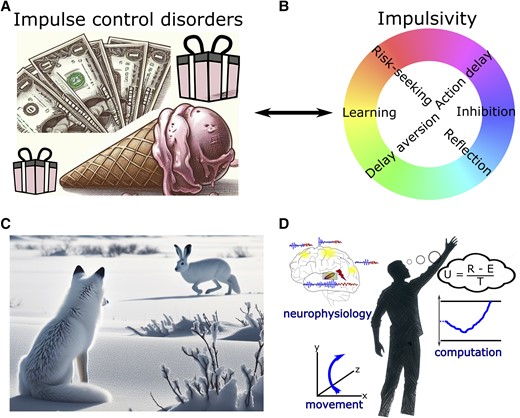

At first glance, there seems to be a discrepancy between the consistently observed DBS-induced impairment in delaying choices in experimental paradigms and the relatively rare occurrence of impulse control disorders (ICD) after STN DBS.147-149 ICD are defined as pathological gambling, compulsive shopping, eating and sexual behaviour along with other abnormal behaviour such as punding, hobbyism and overuse of dopaminergic medication. ICD affect up to ∼25% of medicated PD patients64,148 (Fig. 4A). The prevalence is even higher when considering more mildly affected patients who express impulse control behaviours, which do not sufficiently impact social or occupational function to classify as a disorder.150 Thus, rather than reflecting a categorical (yes/no) entity, impairments in impulse control represent a spectrum of changes in behaviour, which can have a devastating impact on patients’ and their caregivers’ lives when severely expressed. The occurrence of ICD has mainly been linked to dopaminergic treatment, with a particularly high risk of symptom occurrence when using dopamine agonists.65,148,150 While some patients develop post-operative de novo ICD after STN DBS, ICD mostly improve after surgery, presumably due to a reduction in dopaminergic medication.147,149,151 In other words, since dopamine treatment is thought to be the main underlying cause of ICD in PD patients, any reduction of dopamine medication—e.g. when motor impairment is alleviated by STN DBS—will reduce the expression of impulse control behaviours. However, if STN DBS disturbs patients’ abilities to delay choices, as discussed above, thus rendering them more susceptible to deciding more impulsively, why would STN DBS not itself lead to the emergence of ICD?

Clinical implications and outlook. (A) Impulse control disorders (ICD) are defined as pathological gambling, compulsive shopping, eating and hypersexuality along with other abnormal behaviour such as punding, hobbyism and overuse of dopaminergic medication. (B) Spectra of impulsivity comprise distinct underlying mechanisms. (C) In naturalistic behaviour, there is often no clear-cut distinction between functional categories such decision-making, perception and motor control. (D) Illustration of a holistic research approach combining multidimensional measures of brain activity and movement as well as computational analyses of the observed behaviour. In this example, evidence for different options is integrated regarding their utility (U) given by reward (R) subtracted by effort costs (E) and divided by total time (T) to obtain the reward.

An important aspect to consider for understanding the relationship between an impairment in delaying actions and the development of ICD is the multifaceted nature of impulsivity and its underlying mechanisms119,122,152,153 (Fig. 4B). In the paradigms reviewed above, patients mainly show ‘motor impulsivity’, i.e. an inability to hold back an action.154 In contrast to natural environments where decisions often are continuous and extend over time,155 in laboratory settings choices are almost always terminated by an action. Thus, motor impulsivity can lead to quicker, uncorrectable choices at lower levels of evidence. This is sometimes termed ‘reflection impulsivity’154 but is arguably closely related to motor impulsivity in laboratory settings.119 Importantly, despite the evidence considered for such hasty decisions being more strongly affected by noise, the associated choices are not necessarily more risk-prone or delay-aversive, two main aspects of ‘decision impulsivity’.154 Indeed, mechanistic computational models suggest that impulsivity related to risky decision-making and pathological gambling arises from imbalances of striatal dopamine altering the relative sensitivity to benefits versus costs of decisions,156 which is affected by dopaminergic medication but not by DBS.119,157 Thus, dopamine, but not STN DBS, can render PD patients more sensitive to possible benefits and less sensitive to potential costs of choices, and STN DBS, but not dopamine, reduces deliberation time, resulting in more hasty decisions.122,153 If anything, deciding faster might make patients fall back on habitual choices158,159 and PD patients tend to be habitually risk averse.160,161 With few exceptions,162,163 STN DBS has been shown to have no significant effects on patients’ decisions when these are less closely related to the speed of deliberation, e.g. when choosing between smaller immediate versus larger delayed rewards164-167 or learning from negative feedback.119,164,168,169

Together, an impairment in delaying choices due to STN DBS might render people more susceptible to initiate behaviour without proper forethought, e.g. getting up very quickly from a chair despite postural instability.119 However, this mechanism is different from increased reward delay aversion, reduced risk aversion or impairments in negative feedback learning, core processes thought to underlie the development of compulsive behaviours in clinical ICD, which are mainly related to dopaminergic medication.64,148,150,157,170-172

Is it possible to improve motor impairment in PD with STN DBS without simultaneously affecting motor impulsivity? In a hypothetical model of cortico-basal ganglia networks in which decision-making circuits are segregated from movement control, it might be possible to target beta oscillatory activity to specifically affect motor processes leaving decision-making processes unaltered. However, such a model seems incompatible with current views of brain organization and function. Imagine a fox hunting for prey (Fig. 4C). To successfully gather food, the fox needs to e.g. perceive a white hare against a white snowy background, stalk the hare to keep the target in its visual field and decide when and how to attack. In such naturalistic environments, it is impossible to clearly distinguish between decision-making and motor control, since both are continuous and inextricably intertwined.155 Such interactions are also implicated even in simple cognitive studies of task switching, wherein uncertainty about the latent task set rule in prefrontal cortex triggers an STN pause in the motor circuit, preventing premature responses and reducing task-set interference.173 According to this framework, even disrupting STN solely at the motor level will then impair decision-making and increase task-set interference.

Indeed, most, if not all, neural areas involved in decision-making modify and reflect movement174 and evolving decisions can be tracked in brain networks classified as motor.175,176 In DBS studies, decision threshold adjustments can be linked to STN activity changes both in the theta and beta range.10,17,69,73,86 Thus, to some extent, interfering with brain networks for therapy will always have diverse effects due to the multiple functionalities of brain organization (the same network can implement multiple functions).177 Nevertheless, on a more pragmatic level, there is good evidence that progress in spatially-focused DBS as well as adaptive DBS, which only gives stimulation when deemed necessary based on feedback markers, can improve clinical efficacy and spare side effects.178-180 To further advance this exciting field of research, it will be vital to better understand where and when DBS should be applied to optimize effects on abnormal neural activity patterns, even if it might remain fictitious to exclusively modulate one specific behaviourally-defined variable.

Outlook

In this review, we focused on the role of cortico-subthalamic circuits in the controlled delay of actions. However, cortico-basal ganglia circuits subserve a variety of other important functions, such as movement invigoration, action selection and learning.26,28,181,182 Many of these behaviourally defined functions are closely interrelated (e.g. options with higher utility should be more likely to be selected and also be acquired more vigorously)183 and therefore putatively rely on similar or even common neural mechanisms. This could be leveraged for therapy aiming to reinstate functionality that is impaired in neurological disorders such as PD. To this end it will be important to carefully map the effects of DBS on well-defined behavioural changes and their underlying computations. Optimally, this will involve multidimensional neurophysiological measures beyond a single frequency band or recording site,184 precisely controlled stimulation patterns and behavioural measures, including body movement, in studies that are grounded in clear theoretical frameworks allowing specific predictions to be tested106 (Fig. 4D). Since cortico-basal ganglia dysfunction has been implied in a wide range of neurological and psychiatric diseases, the results discussed here might also be useful for the study of other brain disorders and could inform future DBS study designs.180 For example, DBS of the ventro-medial STN is currently being investigated for obsessive-compulsive disorders,185 and a better mechanistic understanding of DBS effects on action control in obsessive-compulsive disorders could advance current treatment strategies. Novel sensing, directional DBS devices51 offer the unique possibility to translate insights from studies using DBS as an experimental tool to clinical therapy, bridging the gap between bench and bedside.

Funding

GBA Innovationsfonds project 01NVF22107 (INSPIRE–PNRM+).

Competing interests

The authors report no competing interests.