Latinization, Local Languages, and Literacies in the Roman West

Latinization, Local Languages, and Literacies in the Roman West

Contents

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

4.1 Introduction 4.1 Introduction

-

4.2 Methodological Challenges 4.2 Methodological Challenges

-

4.3 The Urban Dimension: Status and Size 4.3 The Urban Dimension: Status and Size

-

4.4 Epigraphic Habit within Communities 4.4 Epigraphic Habit within Communities

-

4.5 Regional Variations: The Conventus 4.5 Regional Variations: The Conventus

-

4.6 Conclusions 4.6 Conclusions

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

4 The Epigraphic Habit in Post-Conquest Hispania*: A Geospatial Analysis of the Epigraphic Data and Self-Governing Communities

-

Published:November 2024

Cite

Abstract

This chapter considers the epigraphic habit in relation to the self-governing communities of the early imperial Iberian Peninsula. The entanglement of juridical status, monumentality, epigraphic output, and research bias poses a challenge for interpreting the data relevant for Latinization. However, by turning to macro-level analyses, we can discern general patterns that can be refined by case studies focusing on regions and epigraphic text and material types (for example, the milestones of Bracaraugustanus). The chapter shows that the spread of the epigraphic habit is the result of an interplay between the status of communities and their understanding, or interpretation, of the epigraphic habit. Neighbouring communities tended to engage in intercity rivalry, and those with supra-regional function also tended to compete with communities further away. In order to untangle research bias and diagnose the various factors motivating the epigraphic habit, we must enhance the data further, adding more precise geospatial information.

4.1 Introduction

The continuous process of Latinization that started in the third century bce had far-reaching effects on the linguistic and epigraphic landscapes of the Iberian Peninsula (Chapters 2 and 3). We tend to view the Latinization of the Iberian Peninsula as a teleological process with a clear result. The various forms of modern-day Spanish (Castilian, Catalan, Gallego, and so on) and Portuguese are descended from Latin and contain only relatively few words from their pre-Roman predecessors, and the epigraphic evidence seems to support the relatively quick adoption of Latin as the main language for written communication.1 Even though the Peninsula knew a long history of written languages and saw a major rise in the epigraphic culture of Palaeohispanic languages around the time of the Roman conquest, the Augustan period seems to represent a watershed moment for the massive increase in Latin epigraphic activity and the demise of the epichoric epigraphy. Traditionally most Palaeohispanic inscriptions have been dated to the mid- and late Republic, and all Palaeohispanic epigraphy tends to be dated with the Principate as a solid terminus ante quem. But often dating is based on this preconceived view of the evolution of the language and epigraphy of the Peninsula, rather than direct archaeological or other information. Although the epigraphic record is quite different from that of Gaul, in which Gaulish clearly survives much later (Chapter 5), it may be worth remembering the imprecise nature of much of the dating. While the reality of the language death of the local varieties is not recoverable with any precision, it is unlikely that they suddenly disappeared from oral use under Augustus. In the same way, the Roman language and epigraphy were clearly successful, and at a zoomed-out scale apparently relatively homogeneous, but the reality is one of complexity and regionality in the precise modalities of both.

Although we tend to regard Latinization as a gradual process resulting from the impact of Roman soft power, we must not forget that the Roman conquest was at times violent and based on unequal power constructions.2 The most obvious power behind the initial spread of Latin was undoubtedly the military. But the simple marching of an army through a land will not lead to the adoption of Roman practices and the Latin language; in fact it may result in quite the opposite. It is clear that the advancing lines of Roman conquest do not neatly reflect the tempo of the spread of Latin and the uptake of the epigraphic habit, and indeed, as we have seen in the earlier chapters, the conquest is the context for the expansion of epichoric epigraphy in some regions. Though the military has an impact, to a greater or lesser extent, everywhere, the nature of that impact depends on the nature and speed of the conquest, the economic effects, whether depressive or stimulating, the size and nature of military settlement, and relations with local communities.3 Trade goes, at least in part, hand in hand with the military, and is another key early factor in the spread of Latin. Even though locals could trade with military communities, however, at least at first the army would commonly gather resources by force and later by continuous taxation.4 These interlinked factors of trade and the military are essential for understanding the spread of Latin and epigraphy in the Republican period and to a lesser extent the imperial,5 when the military presence on the Iberian Peninsula after the Cantabrian Wars was limited to one legion.

Both of these elements help to shape the creation and status of the self-governing communities across Roman-period Hispania. The shift from the Republic to the imperial period is formative for the urban fabric of the Iberian Peninsula.6 It is in this period that Caesar and Augustus promote several communities to coloniae with Roman citizenship. The Caesarean coloniae seem to have been ‘promoted’ with a deduction of Caesarian veterans after they supported Pompey. The promotion to colonia meant less freedom and accepting a new elite: the Latin-speaking veterans.7 The status of municipium civium Romanorum, on the other hand, those holding Roman citizenship without a deductio, was granted to the allies of Rome. Similarly, we see that Augustus promotes communities, most likely those that were Latin coloniae, to municipia civium Romanorum. It is likely these promotions were implemented to accommodate the number of inhabitants already holding Roman citizenship through their descent. The communities holding Roman citizenship, such as Ilerda and Caesaraugusta, often had long-standing relations with Rome as allies in the wars. The last major shift in the urban fabric of the Iberian Peninsula is the blanket grant of ius Latii by the Flavians to the three provinces.8 As a result, we find several statuses on the Iberian Peninsula, which each have their own forms of citizenship. The question arises, then, as to whether the nature of these different communities has an impact on Latinization and the uptake of the epigraphic habit.

This chapter analyses the Latin epigraphic record across the peninsula and considers geospatial information to uncover deeper relations between the epigraphic habit (lapidary and monumental metal inscriptions) and the size and status of different communities, in an attempt to reveal the ways in which different communities adapted to, and expressed themselves in, the new Roman context. This analysis combines the latest research on status of settlements with the large LatinNow epigraphic data set, whose geographical attributions have been significantly improved from those of the digital epigraphic feeder projects. Despite the best efforts carefully to curate the epigraphic records, they still form a ‘characterful data set’ (Chapter 1), and this research should be seen as the first steps into a complex issue.

4.2 Methodological Challenges

The collection of epigraphic data is a continuous and uneven process. The LatinNow data for the Iberian Peninsula were collected from several databases, aggregated by the Europeana EAGLE project, with entries mainly up to 2017,9 of which the most important is Hispania Epigraphica Online (Chapter 1). This data set relies primarily on the publications of the epigraphic journal Hispania Epigraphica.10 One of the main issues underlying these digital resources is the nature of the recovery of the epigraphic remains, their publication, and digitization, which are shaped by modern factors. Several elements play a major role in creating a biased record. First, the epigraphic record is strongly dependent on archaeological activity to uncover new finds, and in Spain and Portugal this has traditionally tended to focus on well-known and monumental sites. In addition, epigraphic scholarship itself historically has tended to favour monumental inscription and thus has disproportionately considered the elite. This bias in turn reinforces the focus on the monumental cities, as the elite uses the urban monuments to represent itself. As a result, the everyday writing on small objects, or the so-called instrumentum, are recorded much less often, or with less precision.11 Admittedly, more recently there has been increasing interest in small-finds epigraphy,12 aiding our understanding of the way in which local communities and individuals interacted with writing and literacy (Chapter 7). Despite these efforts and owing to the historical focus on the elite, the epigraphic record has a clear bias towards monumental inscriptions, which together represent what we term the ‘epigraphic habit’ (Chapter 1).

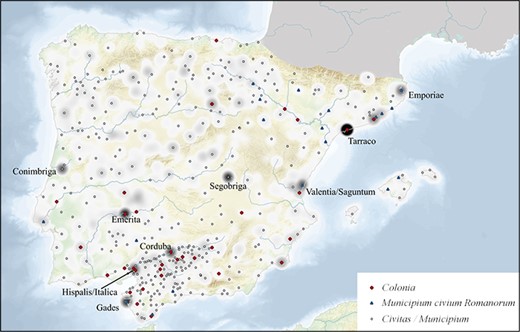

The heat map in Fig. 4.1 shows epigraphic clusters within a radius of 30 kilometres of civilian settlements for the total of all 31,346 inscriptions for the Iberian Peninsula in the LatinNow database. The heatmap was created using 30-kilometre clustering—all inscriptions within 30 kilometres from civilian settlements are used for the clustering algorithm. This radius roughly coincides with the six-hour walking distance that can be considered the maximum territory of a settlement.13 In this way we attempt to count all the inscriptions belonging to a city and its territory. Moreover, epigraphic foci within this 30-kilometre distance are amplified. The upper value has been set to 1,000 inscriptions; this means that places with 1,000 or more inscriptions are rendered black. This upper value is chosen to level the effect of Tarraco with its 2,716 records, and to highlight places with high concentrations. The second largest concentration is found in Emerita Augusta (909). Unsurprisingly we find another high concentration in Corduba (723), thereby completing the list of provincial capitals. These are the centres of imperial power and therefore hold a high concentration of honorific inscriptions dedicated to Emperors, provincial flamines, and local magistrates. All these men, and to a lesser extent women,14 immortalize their memory in the most public and high-status places of the province. Although not a provincial capital, the high number of inscriptions in Gades (793) was to be expected. This city was considered to be of great importance in Antiquity.15 The concentration at Hispalis/Italica near Gades is the result of multiple sites with high concentrations in close vicinity, similar to the area of Valentia/Saguntum.

Heat map of the epigraphic record within a 30-kilometre radius of the civilian settlements.

In addition, we observe some, at least at first sight, more unexpected sites with high epigraphic concentrations: Segobriga (802), Conimbriga (592), and Emporiae (546).16 Although we could perhaps explain the epigraphic richness of Segobriga through its relevance as a mining centre and a city boasting a large monumental core, such arguments do not hold for Conimbriga and Emporiae. More likely, both these high concentrations are the result of research and publication bias. In the case of Segobriga, it is the interplay between the monumental and epigraphic richness of the city, and the resultant interest and publications, that skews upwards the digitized epigraphy of the site.17 The high volume of epigraphic records of Conimbriga and Emporiae is the result of continuous excavations since the mid-twentieth century, in the case of the latter fuelled by interest in Greek colonies.18

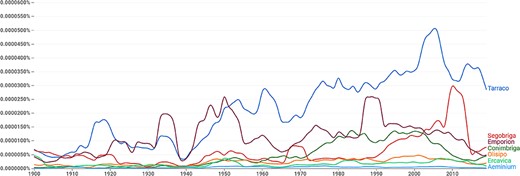

We can observe this potential research bias for Segobriga and Conimbriga with an Ngram that allows us to contrast the attention received in the literature by these places compared to others nearby (Fig. 4.2). The Google Ngram allows us to search digitized books available in Google for specific words. This Ngram was created by searching the Spanish language corpus up to 2019.19 Despite the limits of Ngram (the OCR might be faulty, and our search terms not recognized), the bias towards Segobriga and Conimbriga stands out in contrast to the neighbouring towns of Ercavica and Aeminium. In the case of Aeminium and Conimbriga, we must account for a rather problematic issue: in Late Antiquity the toponym Conimbriga shifts with the seat of the bishop to Aeminium. As such, Conimbriga might refer to both Condeixa-a-Velha, Roman Conimbriga, and Coimbra, the later bishopric located at Roman Aeminium.

Google Ngram of publications mentioning places from 1900 onwards.

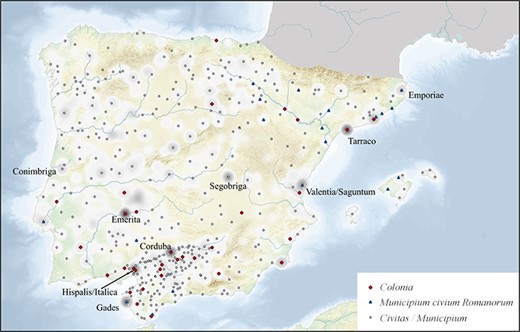

When we turn to the heat map showing only the inscriptions we regard as representative of the epigraphic habit (Chapter 1)—namely, Latin inscriptions on stone and monumental metal—we can observe the effect of this research bias (Fig. 4.3). Conimbriga (129) and Emporiae (179) are suddenly less prominent; in the case of the latter this is related to the attention that has been paid to the non-lapidary inscriptions in Greek and Iberian. Similarly, we find that Tarraco has gone from 2,716 records to only 586. These drops are an indication of the completeness of their records: for these locations, besides the traditionally collected monumental inscriptions, researchers have recorded many smaller inscribed finds and added these to the online databases. The less significant drops in other cities may signify a research focus on monumental inscriptions, while everyday inscribed objects have not been studied with much attention or have not yet made it into the databases that form the basis for our data set. In order to avoid studying the research bias, or creating conclusions resulting from this, we have to be aware of the modern patterns and, for the zoomed-out scales of analysis, are forced to focus on the more evenly studied subset of ‘epigraphic-habit’ inscriptions.

Heat map of inscriptions relating to the epigraphic habit within a radius of 30 kilometres from civilian settlement.

The geospatial approach faces a challenge, since the digital epigraphic data sets use inadequate spatial data. Historically, in the CIL corpora the epigraphy was attributed to an ancient place. Turning to CIL II, for the Iberian Peninsula, we find that the first place is Ossonoba (Faro), with the additions of S. Bartholomeu de Messines, Loulé, Boudens, and Fuzeta.20 This organization led the earliest digital data sets, such as EDCS, to follow this approach of assigning inscriptions to the main known local ancient place, with reference to the modern name associated with that ancient place. Clearly, this approach creates issues when an ancient city is located between two modern places, or when its original location is disputed. In order to overcome these issues, the Hispania Epigraphica journal organizes its sections by country, then modern divisions in alphabetical order.21 Spain is organized following the hierarchical organization into provincia and municipio, whereas Portugal is organized following distrito, concelho (also município), and freguesía. Where possible, a more specific location within the municipio or freguesía is given for the individual inscriptions. This shift has led to the attribution of the epigraphy to a wider range of modern places, which for the epigraphy that does not hail from the major urban centres can be more useful.

However, the problems continue when we want to attribute coordinates to the locations attached to our epigraphic records in databases in order to undertake GIS analysis. Rather than finding that our epigraphy is located using their individual location, we encounter the issue that it is attributed to the modern local municipality. In the cities with continued habitation, the centroid is generally on, or at least near, the archaeological site. However, when the ancient city is a green-field site, the chosen centroid is often located at the nearest modern municipal capital, leading to the dislocation of the epigraphy. The example of the epigraphy of Tróia is illustrative. This port settlement at the estuary of the Sado is located 45 kilometres from Grândola, the municipal capital to which Tróia’s epigraphy was attributed.22 Where possible in the LatinNow data set we have relocated the epigraphy to the ancient place, but finite resources meant that we were not able to improve the data for all the epigraphic locations. Researchers using the standard online epigraphic data sets should be aware of these issues.

For the epigraphy concentrated in ancient civilian settlements, changing the location in the data sets from, say, the modern municipal capital to a more precise ancient site can be a rather straightforward bulk computer operation where we have the archaeological information. Unfortunately, another problem is that epigraphy belonging to the broader territory of ancient cities has commonly incautiously been geographically attributed to the ancient cities controlling the territory (and thus often to the associated modern places). Occasionally this occurs in the print publications themselves, but more commonly this is a product of ‘streamlined’ digitization, whereby inputters find it easier to use a site already stored in the data set. Thereby the epigraphy of hinterlands tends to be aggregated in the same modern places as the urban epigraphy, losing crucial information to reconstruct the complexities of urban–rural patterning, including the reconstruction of dispersed rural settlements. If we think about the same happening to milestones, we would lose valuable information on the location of roads. The modern organization into municipalities is more finegrained than in Antiquity: Pliny gives 513 civitates for the entire peninsula, whereas we find 308 municipalities in Portugal and 8,118 in Spain. As a result, the modern system in some cases leads to the attribution of some of the rural epigraphy to other places nearer to the original find-spot than the ancient cities, but still not necessarily close to the location of the ancient display.

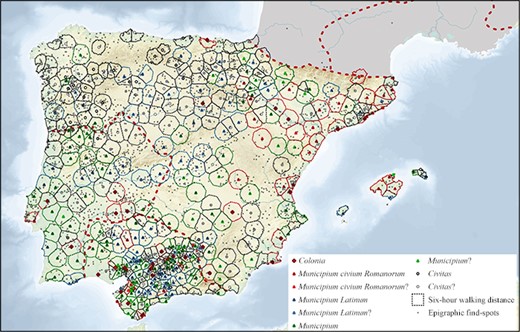

With these issues of research bias towards monumental inscriptions and the aggregation of epigraphy in modern places in mind, at the broad scale of analysis we must find ways to study the epigraphic record while trying to mitigate these deleterious effects. To counter the effect of the dislocation of epigraphy from ancient sites because of their attribution to modern ones, we have used a 5-kilometre radius from the urban centres, to identify epigraphy that might be considered ‘urban’. Though this may be an inadequate solution compared to detailed record-by-record geo-referencing, and does not rescue the rural epigraphy that has been erroneously sucked into the centres, it can serve as a useful interim workaround. In addition, as we lack knowledge of the territories of the civitates, I have reconstructed these by establishing territories based on a six-hour walking distance.23 Most areas of the peninsula are covered when using this distance (Fig. 4.4), but roughly a tenth of the epigraphic record is found outside these reconstructed territories, in what I shall call ‘extra territorial’ areas. These epigraphic concentrations will be discussed briefly below, and, as they are far from known centres, in future research they could help us recover not yet found centres of population or provide information on how peripheral territories were organized.

Epigraphy, juridical status, and the constructed six-hour territories.

A perennial issue that we have not yet touched upon is the dating of the texts. Dating epigraphic texts is a well-known challenge for several reasons. First, the objects on which the inscriptions appear are prone to be reused as spolia, thereby appearing in a later archaeological context than the inscription itself. Moreover, the inscriptions collected in the large nineteenth-century corpora often tend to lack their archaeological context. As a result, epigraphists resort to various ways of dating inscriptions using the object and text, rather than the archaeological context. In rare cases we find a clear date within the text as it includes consular dating, the reign of the Emperor, or other clearly dateable historic events. Interestingly, inscriptions with such obvious internal dating are often published without stating the date. For those familiar with the reigns of the Emperors or other historic events, it is perhaps deemed not necessary to note down the year, as it clearly appears in the inscription itself.24 However, this practice is unhelpful for two reasons: first, it feels like a form of gatekeeping that reduces the accessibility of the field; second, these internal dating elements are not machine readable, making them less useful for analyses such as those deployed in this volume.

More commonly, we have to resort to other less direct forms of dating, such as formulae, iconography, and palaeography.25 For example, the formula hic situs, or sita, est, is considered to be in disuse from the third century, and is dated by Raepsaet-Charlier specifically to the first century ce.26 Similarly, the formula Dis Manibus or DM is considered to start in the Flavian period and has ended by the fourth century.27 Such generalizations aid in giving broad dates to inscriptions. In addition, these formulae are considered pagan, in contrast to Christian formulae such as in pace and fidelis that tend to appear from the third century onwards.28 From these formulae, we might begin to think that there is a clear separation between pagan and Christian epigraphy. However, such assumptions might obscure interesting outliers, like the Late Antique (sixth or seventh century ce) inscription from Kaiseraugst, which starts with the formula DM.29 Moreover, if we use the truisms mentioned above to date epigraphy, we will find that epigraphic formulae tend to follow our dating categories perfectly. We have created a circular reasoning in dating methods.

Since the subset of the inscribed objects for the Iberian Peninsula had only a small set of dated inscriptions, and we have not had sufficient time consistently to improve the dating of the epigraphy for the Iberian Peninsula, I have been forced to proceed without detailed chronological data, though where subsets allow the evaluation of chronological patterns I do so.

4.3 The Urban Dimension: Status and Size

The fact that we find 58 per cent (18,279 inscriptions) of all epigraphy of the peninsula within 5 kilometres of a self-governing centre demonstrates the importance of these centres for the epigraphic output, although, despite our improvements to the geo-coordinates, as we have seen, the skewing of the geographical attribution caused by the issues discussed above will have inflated this number. Beltrán links the Plinian humanissima ambitio (Plin. HN 34.17) directly with public places, especially those in the cities.30 The presentation areas for epigraphy are the fora, the spectacle buildings, and other places of gathering. Even within the private sphere, the humanissima ambitio is expressed epigraphically in the atrium, the public area of the private house.31 Clearly public display and cities were important in the spread of Latin and the epigraphic habit,32 but not all cities are the same, and understanding the different status and sizes of urban settlement in the Iberian Peninsula and their diverse epigraphic records may allow us to understand better the dynamics of the epigraphic habit and its drivers.

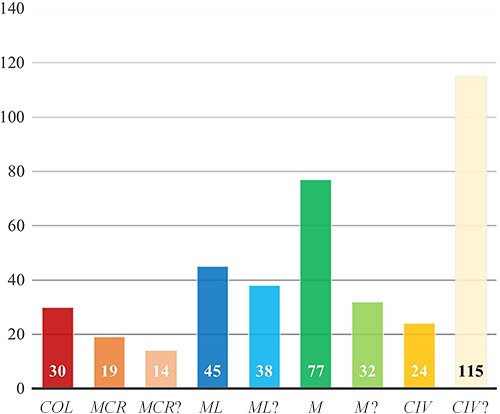

As a result, we have to establish the juridical status of the communities. These statuses change over time, which naturally causes complexity for mapping and analysis. Thankfully, the juridical status of the communities changes relatively little on the Iberian Peninsula over time. We observe ad hoc grants in the Republican period—for instance, the communities granted Latin status recorded by Pliny. Roman citizenship was mostly granted during the Julio-Claudian period.33 Thereafter we find the grant of ius Latii by the Flavians promoting most communities without a status to Latin municipium. In contrast to other provinces we do not see a gradual promotion of municipia to honorary coloniae in later periods. The only exception is Italica, which is promoted by Hadrian upon its own request.34 Therefore, the situation is relatively stable by around 100 ce, and we have opted to use the statuses known at that period for our analysis.35 I prefer to use the term communities when dealing with juridical status, as a status (for example, colonia, municipium) is granted to the whole community (city and territory) rather than a single city. Moreover, not all self-governing communities are urban.36 Based on the available information I have differentiated between coloniae (COL), municipia civium Romanorum (MCR, holding Roman citizenship), municipia Latina (ML, with Latin rights), municipia (M) without known rights, and civitates (CIV). All these statuses are directly supported by literary or epigraphic sources.37 In addition to the certain categories we have to add uncertain ones. The uncertain municipia civium Romanorum (MCR?) are the oppida Latina as mentioned by Pliny in his Naturalis historia, which it seems likely became Roman municipia in the Julio-Claudian period. The possible Latin municipia (ML?) have the Quirina tribus attested, but do not mention municipium in the epigraphic record. Pliny mentions several communities with reference to their status; these are the uncertain municipia (M?), as they are likely to have been promoted, and within this category we also find communities with an attested tribus. The uncertain civitates (CIV?) have indirect evidence for a self-governing status; either they have magistrates or they refer to res publica. With these categories, we can assign a status to all known self-governing communities of the Iberian Peninsula (Fig. 4.5).

Statuses of self-governing communities of the Iberian Peninsula (total 394).

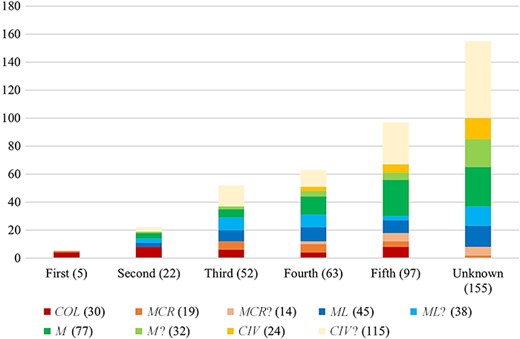

Another element of importance is the size of the civilian centre. Large cities tend to have more epigraphy simply because more people lived in these cities, and more people were commemorated with funerary and honorific epigraphy. In an earlier publication, I organized 239 cities on the Iberian Peninsula into five size categories (Fig. 4.6) (the remaining 155 could not be categorized owing to uncertainty over their extent):38

80 hectares and higher;

40 ha (incl.) to 80 ha (excluding 80);

20 ha (incl.) to 40 ha (excl.);

10 ha (excl.) to 20 ha (excl.);

10 ha (incl.) and lower.

Size distribution of cities on the Iberian Peninsula (total 239).

The geographic distribution of the lower four categories is rather equally spread over the Iberian Peninsula. However, the largest five cities are concentrated on the Mediterranean coast and the southern part of the peninsula. These five consist of the provincial capitals (Tarraco, Corduba, and Emerita Augusta) and two important pre-Roman cities (Gades and Carthago Nova).

The combined data of size and status show that the higher-status communities also tend to be the larger communities (Fig. 4.7). The five largest communities all held Roman rights; the sole municipium civium Romanorum among the five largest is Gades. Though there are only 30 coloniae out of 394 communities, they are overrepresented in the larger-size tiers. Similarly, we see that the municipia without known rights, and the civitates, are concentrated in the lower tiers.

Distribution of status of community across size of cities of the Iberian Peninsula (total 394).

When mapping the juridical status of the communities, we have to keep a few caveats in mind. First, as stated above, not all communities are centred on a clear urban settlement; however, to have the community represented spatially, I have chosen a centroid to be able to include them in the analysis. In addition, some communities are attested only in the Graeco-Roman literary sources or the epigraphic record, without providing any location for the community. For instance, the Grallienses are attested only in an honorific inscription set up for a provincial flamen originating from this community:

M(arco) Sempr(onio) M(arci) filio / Quir(ina) Capitoni / Gralliensi adlecto / in ordine Caesaraug(ustano) / omnib(us) honorib(us) / in utraq(ue) r(e) p(ublica) s(ua) f(uncto) / flam(ini) p(rovinciae) H(ispaniae) c(iterioris) / p(rovincia) H(ispania) c(iterior).39

From this one inscription, it is clear that the community was a municipium Latinum based on the fact that Marcus Sempronius Capitonus held all magistracies (omnibus honoribus) in his own community and that he was admitted to the tribus Quirina.40 There are about thirty-six of these unlocated communities, and these have been ignored for our analyses, as we cannot attribute epigraphy to these communities, other than the single finds mentioning the name.

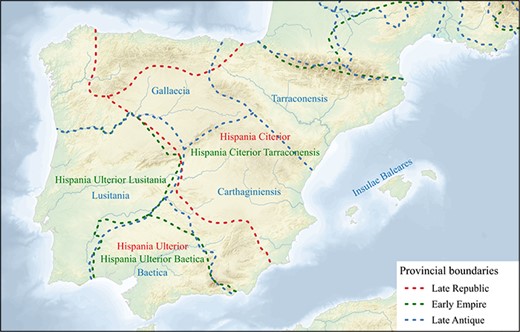

The geographical distribution of the status categories over the peninsula shows some interesting patterns (Fig. 4.8). The main concentration of communities holding the Roman citizenship, coloniae and municipia civium Romanorum, lies in the south-east of the peninsula, whereas we see that the civitates are the most common self-governing communities of the north-western part. The correlation with the area under Roman control by 154 bce is striking (see Chapter 2, Fig. 2.3), and it is likely that members of these communities were collaborating with the Roman power. In this context, it is worth drawing attention to the 89 bce decree by Cn. Pompeius Strabo known as the Ascoli bronze (CIL I2 709), which grants Roman citizenship to the turma Salluitana after the battle of Asculum.41 The Plinian reference to the colonia Caesaraugusta (Zaragoza) by its old name oppidum Salduba may possibly be interpreted as related to the turma Salluitana.42 The bronze also mentions soldiers originating from Ilerda. Hartmut Galsterer points out three soldiers from Ilerda mentioned by duo nomina.43 As it is very unlikely that the three soldiers were all granted Roman citizenship virtutis causa; it is more likely that Ilerda was a community with Latin rights prior to 89 bce.44 Similarly, Natalie Barrandon argues that Ilerda was an early Roman stronghold on the frontier, basing her argument on the early coinage of Ilerda (iltiŕta) and the fact that Pliny mentions this as the capital of a regio.45 These early interactions support the early uptake of Roman citizenship, early intensive contacts with Latin-speaking actors, and use of epigraphic medium to record status.

It is to be expected that communities with different juridical statuses may have participated differently within the epigraphic culture. From imperial edicts such as the Tabula Siarensis, it is clear that the Roman state expected the diverse communities to engage in different ways. The Tabula Siarensis stipulates it should be on display in the coloniae and Italian municipia,46 thereby clearly excluding provincial municipia and other civitates. It is interesting to note that Siarum as a municipium in Baetica was not expected to put this on display, but decided to do so anyway. I have argued elsewhere that this is the result of the ambition of Siarum to try to outdo its neighbours.47 The question arises whether we can document different epigraphic cultures based on juridical status.

4.4 Epigraphic Habit within Communities

To avoid the aforementioned issues of research bias, we will focus on the inscriptions that are considered to be part of the epigraphic habit, which make up a large set of 16,876 inscriptions. However, there is a strong incentive in any case to use this subset, since, if there is a correlation between juridical status and epigraphic practices, it will perhaps be most obvious in contexts of public display, and therefore the epigraphic habit will be the most likely medium for its expression.

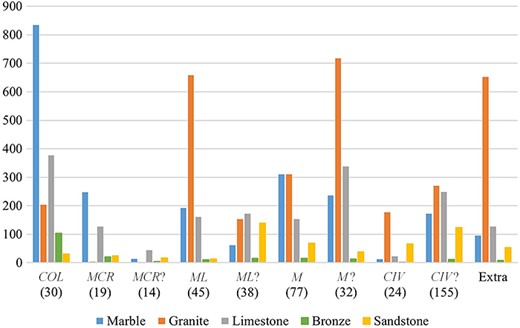

The coloniae stand out in the results of the analysis of the distribution of records of the epigraphic habit subset across the communities of different juridical status (Fig. 4.9): 22.4 per cent of all inscriptions, 4,122, are found within this small set of communities (coloniae and their territories). These 30 coloniae represent less than one-tenth of all communities. Expanding our enquiry to all 63 communities holding Roman citizenship (coloniae, and certain and uncertain municipia civium Romanorum), we see that these 16 per cent of the communities produce one-third of the epigraphic-habit inscriptions. This over-representation can be explained through various overlapping effects: these Roman communities are over-represented in research owing to the research bias towards these communities; they tend to have larger cities and territories (Fig. 4.7), and therefore higher numbers of inhabitants; and, finally, epigraphic display was an element of inter-city rivalry, which we expect to find in these higher-status communities that were participating in the wider Mediterranean sphere.48

The distribution of epigraphy (epigraphic-habit subset n = 16,876) across the different juridical status and differentiated for urban (dark) and rural (light) epigraphy.

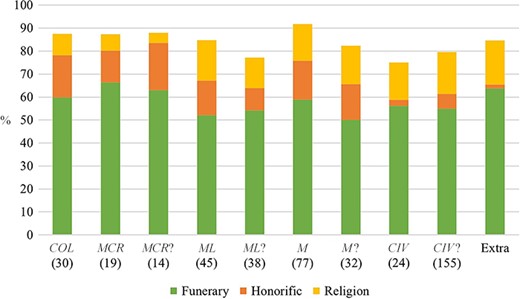

Another way to explore differences in the epigraphic records of diverse community types is in the text types deployed in the corpus for each. Once again, we must keep in mind that the data have limitations and must seek safety in numbers. Owing to the large variability in total numbers of epigraphy between the communities of different status types, I decided to focus on the percentages of text types within each assemblage of inscribed monuments.

In the results visualized in the bar chart (Fig. 4.10), we see the percentages of funerary epigraphy within the total of the epigraphic-habit subset per community status, showing a variation of between 50 and under 70 per cent.49 The variation in our data set does not show any patterns that could explain the higher number in Roman communities. The slightly higher percentage of funerary epigraphy in the Roman communities might simply be related to the size of the cities. As we have seen in Fig. 4.7 the communities holding Roman citizenship are over-represented in the larger urban communities. The size distribution is based on the size of the built-up area of the cities, disregarding the population density of the cities. Since coloniae tend to be more densely populated, the bias towards these communities as population centres is even stronger.50 Moreover, the higher-status communities tend to follow the classical model of city and territory, leading to a concentration of the necropoleis and epigraphic record in the urban centre. The Latin communities and civitates without known status tended to adopt dispersed settlement patterns.51 As a result, their epigraphy is less concentrated (see Fig. 4.9). This might have led to an under-representation, as we have not yet located the smaller epigraphic foci of the multiple necropoleis within a community.

Relative distribution of funerary, religious, and honorific inscriptions within the epigraphic-habit subset by community status.

We should consider funerary epigraphy when thinking about intercity rivalry through epigraphy, since the funerary streets leading into the cities are in a way the first calling card of the city and its epigraphic habit. However, a much more relevant type of epigraphy for intercity rivalry was honorific epigraphy.52 Pliny the Elder relates that the increase in honorific epigraphy testifies to the ambitions of the local elite and that public display was a means of confirming and reinforcing their status.53 The inscriptions honouring the Emperor or governor demonstrate the relationship of the community with the current power.54 And dedications to the local elite show engagement of the community with the practices of the wider epigraphic koine, and an intention to reinforce the position of the community in the grander scheme. Add to this those honorific inscriptions honouring the local elite that had risen to power, and we see how the various honorific inscriptions add to the grandeur of a community. The urban centres were the focus for the elite representation, with the fora and other public places the preferred locations for honorific statues with their inscribed pedestals.55 The choice of Latin shows the ambitions of the elite to engage with the Latin-speaking world and in particular to emulate and ingratiate themselves with the new ruling class. We find examples of the elite starting to use Latin immediately after the promotion of the community. A telling example is the bronze-lettered inscription commemorating the euergetic act of Proculus(?) Spantamicus at Segobriga, which has been dated, along with the forum it records, to the early first century:56

[- - -? Proc?]ulus Spantamicus La[- - -]us forum sternundum d(e) s(ua) p(ecunia) c(uravit-erunt)

The name Spantamicus is of Celtiberian origin and the -icus ending is a Latinized form of the Celtiberian familial name suffix -ko- in epichoric inscriptions.57 It is interesting to see the local elites engage in euergetism immediately after the promotion of Segobriga and use Latin in such a public sphere. The epigraphic modes of honorific inscriptions and the related euergetic dedications in Latin are swiftly incorporated.

Honorific epigraphy is closely related to the political organization of the communities. Political positions were acquired by election by the people, so public recognition was essential. Apart from being from a well-known elite family, the elite had to gain the favour of the people, often by euergetism.58 If successful, these euergetic acts were then recognized by the people through honorific statues and inscriptions. In addition, the erection of a statue also showed that the dedicator had the power to give the necessary recognition to the individual being honoured. In the majority of cases, the erection of honorific statues was a matter for the ordo decurionum, the elite in charge of the city’s administration, and the role of the community was that of spectator. In the few cases in which the community was involved in erecting an honorific monument, it was allowed to ‘borrow’ the power of the elite. Regardless of the dedicant, the honorific inscriptions served to highlight the social status of the person being honoured and were an integral part of the political system of the communities holding citizenship.

The distribution of honorific epigraphy (Fig. 4.10) shows that most communities tend to take part. Unsurprisingly, the communities that stand out through a low ratio are the civitates without specific citizenship rights and the ‘extraterritorial’ areas. The latter are a problematic bunch, as these are outside the six-hour-walking-distance territories of the located communities. Here we expect to find some of the unlocated and unknown communities described above.59 In addition, there are areas too inhospitable for urbanism; these were either uninhabited or might have had other functions. The low ratio of honorifics in the civitates must be seen in the light of a different political organization, in which the duet of euergetism and honorific epigraphy plays a less significant role. Further research might investigate the people honoured across these categories of community; it would be expected that the honorific epigraphy in the civitates honours the Emperors, as honouring the local elite may not have held such an important social function.

The pattern shown by the ratio of religious epigraphy is rather surprising. Here we find that those communities holding Roman citizenship are less well represented (Fig. 4.10). We have to keep in mind that we are dealing with ratios and not the real numbers. This lower ratio indicates only that a smaller section of the epigraphic habit is oriented towards the religious epigraphy. Despite this caveat, we can explain the higher ratio of religious epigraphy in lower-status communities and in the extraterritorial regions, as the result of sanctuaries such as that of Endovellicus at São Miguel da Mota and of Lar Berobreus at Monte do Facho de Donón.60 These supra-regional sanctuaries tend to have higher concentrations of epigraphy than the neighbouring communities, as they perform a religious function for a large territory. The sanctuary of Endovellicus at São Miguel da Mota holds eighty-eight religious inscriptions,61 and the sanctuary of Lar Berobreus about one hundred altars, of which two-thirds offer an inscription.62 Interestingly, these sanctuaries, located at mountain tops, are dedicated to local deities. Although it seems likely that these sanctuaries, with their local divinities, are continuations of pre-Roman sanctuaries, the archaeological evidence for this continuation is often lacking.63 Despite the lack of evidence of pre-Roman religious activities, the naming of the deities indicates local origins. Based on ceramic evidence, the sanctuary of Endovellicus can be dated from the Julio-Claudian period to the late second or early third century.64 The presence of marble from the nearby mines, which started in the Augustan period, and the uptake of the habit to erect altars with votive inscriptions, show either the relatively quick uptake of new habits and religious practices within an existing religious practice, or the quick uptake of local deities by ‘Roman’ actors in the Augustan period.

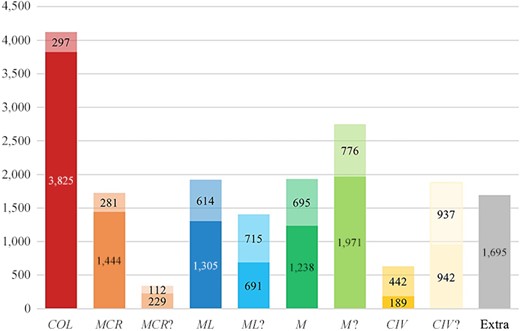

Another approach in the exploration of the diverse epigraphic profiles of communities is to consider the materiality of the epigraphy. We shall take a look at the most common material types found in the epigraphic-habit subset, stone and bronze, excluding inscriptions for which the type of stone is unknown (Fig. 4.11). ‘Stone’ without specification is the most common category, since the original publications often do not specify the material type, and without autopsy and further investigations it was not possible to establish which type of stone had been used. In addition, we find that some databases opt to attribute stone as the default material category when the material is unknown. Clearly, such an assumption is hugely problematic when it is extended to all epigraphic records, given that numerous small finds of ceramic and metal then disappear into the ‘epigraphic-habit’ category. It came as a surprise to discover just how many inscriptional records from the Iberian Peninsula had been wrongly categorized as being on stone in the original data set. During the LatinNow project we corrected such mistakes as far as possible (Chapter 1). However, for the Iberian Peninsula, records with the category ‘stone’, given the imprecision, were left out of this analysis.

Absolute distribution of most common material types, within the epigraphic-habit subset.

The most commonly found material types in the epigraphic-habit subset are granite (2,554), marble (2,106), limestone (1,615), sandstone (572), and bronze (194).65 The use of these materials shows some interesting distributions. The coloniae tend to prefer marble for their epigraphic output. In addition, we find that bronze epigraphy is used significantly more often by coloniae than any other settlement type. However, we must not forget that bronze is not that durable, as it tended to be reused, and this certainly is the explanation for the low overall number of bronze texts.66 This preference for marble raises the question whether coloniae are located near the marble quarries or have better access to marble, or whether this decision requires particular cost and effort.

The distribution of stone types shows an unsurprising correlation with the geological spread of the stone (Fig. 4.12). Granite and limestone especially are used within the regions of origin. Unsurprisingly, we find that marble, as a highly valued stone type, is spread out well beyond the quarries in the southern part. Moreover, we observe that some coloniae tend to have a particular preference for marble. Along the Mediterranean coast, Tarraco and Carthago Nova stand out as coloniae preferring marble. In addition to the local marble, we must also consider their access to imported marble, although this would most likely be used for decoration.67 However, the spread of marble in the region where marble was quarried indicates that local use was an important driver for the production of marble inscribed monuments. For example, near the Estremoz/Vila Viçosa quarries, we find a large concentration of marble without a town. This is the sanctuary for Endovellicus, where we find that votive altars tend to be erected in the local marble.68 Nonetheless, even in the region where marble was quarried, and even though it is found in the sanctuary of Endovellicus, the use of marble is mostly found in the coloniae. As such, Emerita Augusta, Corduba, Astigi, Hispalis, and Italica stand out in Baetica. As a Roman municipium and important town in the west, we find that Gades also prefers marble over other materials. This concentration and those in Ebora, Myrtilis, and Celti can be explained by the combination of the availability of marble for the communities and the intercity rivalry.69 As I have argued before, we can observe this in monumentality and epigraphy.70 As marble is a valued and expensive material in antiquity, it is prone to be used as a measure to show the wealth and prestige of individuals and the community as a whole.71 In this light of intercity rivalry, we can see the use of precious materials in cities such as Ebora and Myrtilis. Both cities are older than the ex novo Augustan foundations of the conventus capital Pax Iulia and the provincial capital Emerita Augusta. The imperial project favouring the new cities gave these the upper hand, in prestige and relevance, as assize and economic centres. The local elite in the older towns wished to show their importance to the local population and the new, imperial-backed elite. What better way of defeating the new players than in their own game. Local elite thus borrowed the ‘language’ of the new power literally and visually by engaging in the epigraphic output and monumentalization. These relations between old cities and their newer promoted counterparts led to a rivalry that can be seen playing out in their inscribed stones.

Distribution of stone types granite, marble, and limestone used in epigraphic output and marble quarries.

4.5 Regional Variations: The Conventus

Hispania has been described as a micro-European continent, based on its heterogeneous geography and cultures (see also Chapters 2 and 3).72 As such, the macro-level approach above on cities and status across the whole peninsula provides a rather limited view that overlooks this regionality. In order to obtain some regional approaches, we could turn to the provinces of Hispania. However, these come with their own problems. First of all, the provincial divisions were not as stable as we often seem to think. For the first decades of the conquest, up to 197 bce, the peninsula was considered one provincia. After 197 bce, it was divided into Hispania Citerior and Hispania Ulterior, roughly dividing the peninsula into a north-eastern half and a south-western half (Fig. 4.13). Augustus then divided the peninsula into three provinces: the senatorial province Hispania Ulterior Baetica and the imperial provinces of Hispania Ulterior Lusitania and Hispania Citerior Tarraconensis. The boundaries of the imperial provinces are often considered as fixed lines; however, they were far from so.73 The next significant reorganization took place under Diocletian, where Hispania Citerior Tarraconensis, the largest province of the Empire, was divided into four smaller provinces: Tarraconensis, Gallaecia, Carthaginiensis, and Insulae Baleares.74 Under this reorganization the diocese Hispania was created, which also included the provinces of Lusitania, Baetica, and Tingitana, across the Strait of Gibraltar.

The provinces of the early Empire were subdivided into conventus: Hispania Citerior Tarraconensis into Carthaginiensis, Tarraconensis, Caesaraugustanus, Clunienses, Asturum, Lucensis, and Bracaraugustanus; Hispania Ulterior Baetica into Cordubensis, Astigitanus, Hispalensis, and Gaditanus; and, lastly, Hispania Lusitania into Emeritensis, Scallabitanus, and Pacensis. These subdivisions might be more helpful than the larger provincial areas for exploring local differences, as they partially follow geographical and cultural patterns.75 For instance, the conventus Gaditanus covers the coastal area of the Mediterranean Façade, a region previously under the control of Phoenicians and Carthaginians. Admittedly, the Celtiberian area was divided up into three different conventus, showing that these earlier linguistic and cultural groups were not necessarily, or perhaps occasionally deliberately not, the basis for the divisions.76 Nonetheless, these subdivisions are units we can use to observe some local patterns.

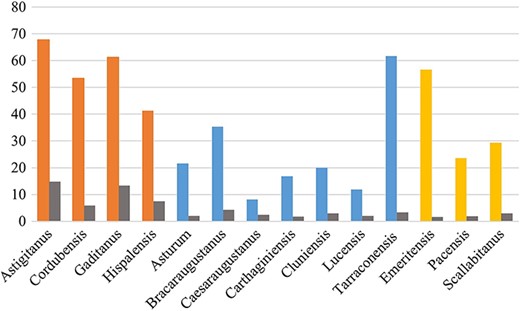

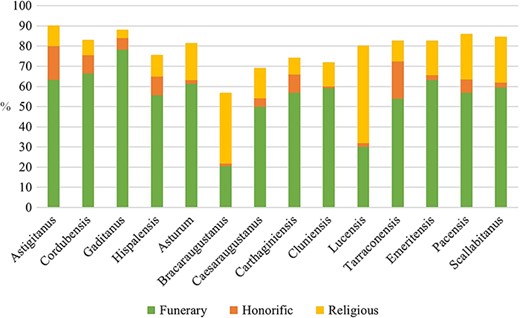

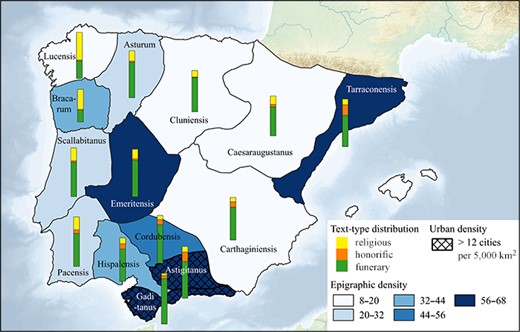

Fig. 4.14 indicates that regional differences are striking across the Iberian Peninsula. At first we notice that the conventus of Baetica (orange) have rather high epigraphic concentrations. This is not surprising, as these regions have the highest urban density of the peninsula and are among the highest of the Roman west.77 Surprising is the fact Astigitanus has the highest epigraphic density, as, in contrast to Gaditanis, Tarraconensis, and Emeritensis, this conventus does not hold a large and important urban centre. The highest concentrations in the provinces of Lusitania and Citerior/Tarraconensis are found in the conventus of the provincial capitals: Emeritensis and Tarraconensis. These cities are prolific epigraphic centres, as they concentrate the local, regional, and imperial juridical and religious functions and therefore tend to draw in the elite. These are the centres where the ambitious elite Pliny alluded to are most present. Similarly, but on a much smaller scale, we can understand the small towns as foci for epigraphic output. When we turn to urban densities, we observe that Astigitanus also holds the highest urban density, though it does not have a major single centre, supporting the idea of urban density as an epigraphic focus.

‘Density’ of the epigraphic habit per conventus. Provinces coloured as follows: Baetica orange, Tarraconensis blue, Lusitania yellow. The urban density (number of cities per 5,000 kilometres2) is in grey.

Urban density is not the whole story in the explanation of the epigraphic densities. We need to remind ourselves of the potential skewing effect of large coordinating publications: the second edition of CIL II (Hispaniae) is appearing in phases and CIL II2 Pars XIII Conventus Carthaginiensis has only recently been published, and its possible impact would not have been felt in our data. Pars XIV conventus Tarraconensis came out in 1995, 2011, 2012, and 2016, and has therefore mostly been ingested into our data set; the same goes for Pars V Astigitanus (1998) and VII Cordubensis (1995). Bracaraugustanus may feature surprisingly high on the list, thanks to concerted efforts of Portuguese scholars to document this region.

In order to compare the epigraphic profiles of these regions and to overcome the issues of research bias, we turn again to the three main text types of epigraphy: funerary, honorific, and religious epigraphy. Fig. 4.15 shows the occurrence of the three main text types within the records of the different conventus. The stacked columns show what proportion the main types take in the whole epigraphic record of that conventus. For example, in the case of Astigitanus, the funerary epigraphy takes up 63.6 per cent, the honorific epigraphy 16.6 per cent, and the religious epigraphy 9.7 per cent, encompassing almost 90 per cent of all epigraphy from that conventus. Bracaraugustanus stands out with a relatively high epigraphic density (Figs 4.14 and 4.16) and an underrepresentation of the main types of lapidary epigraphy; these count up to a mere 57 per cent of all epigraphy (Fig. 4.15). This raises the question where the high density is coming from, and what epigraphic types make up the remaining 43 per cent. It appears that 31.7 per cent of the epigraphic-habit text type in Bracaraugustanus is made up of milestones.

Relative distribution of the most common epigraphic text types by conventus.

Geographical distribution of the epigraphic density and text types per conventus, indicating the conventus with the highest urban density.

The overview map in Fig. 4.17 shows that we find a few areas of the Iberian Peninsula with a higher concentration of milestones. However, when comparing these areas with Bracaraugustanus, we observe that in this particular region the concentration is considerably higher. There are clusters of several dozens of milestones along some stretches of the roads, something we do not find in other regions. The intense concentration of milestones in this region is hard to explain, and seems unlikely to be down to research bias.78 The first explanation that springs to mind is that for some reason the officials in this peripheral corner of the Roman world had an unhealthy fear of getting lost. Campedelli relates the high number of milestones to mining activities and the need for good roads to extract the precious ores.79 This interpretation seems to be supported by the high concentration along the Vía de Plata, as the main artery to the south. However, we would expect to find a much higher concentration in the Sierra Morena to support the relation between mining and milestones (see Fig. 4.17). All milestones in this region are instead found near Corduba, rather than on the roads leading from the mines. Turning to the texts of the Bracaran milestones, as often with markers of space, we observe that these milestones are not merely milestones, but some of them also doubled as honorific inscriptions to the later Emperors. Sergio España Chamorro points out that Augustus reorganized the provinces and renovated the roads of Hispania; moreover, he adds that placing milestones in rural and peripheral areas could be a way to extend and implement Roman culture.80 This observation is interesting, as it might partially explain the high concentration in the region, as the roads in the north-west linked the conventus capitals of Bracara Augusta, Lucus Augusti, and Asturica Augusta, all three cities founded by Augustus. It is indeed very likely that this imperial project was completed with the milestones to show the agent of the reconstruction and reorganization of the territory. In addition, it would advertise Latin as the language of those that hold the power to implement these reorganizations.

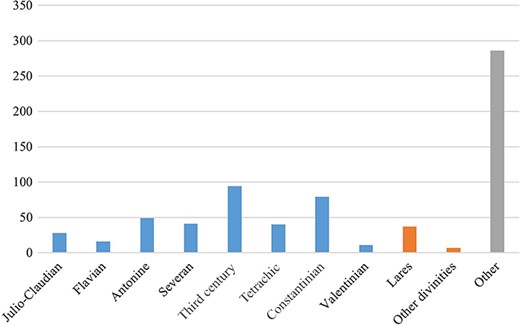

However, this explains only the Augustan, possibly the Julio-Claudian, milestones in the region, which make up only 7 per cent of the inscriptions mentioning an Emperor. Most of these stones pertain to later periods (see Fig. 4.18). This raises the question why we see such a low number of milestones for the Principate. One interpretation could be that these were erected only at the first construction of the road and later on when major renovations were needed in Late Antiquity.81 However, we cannot rule out the possibility that older stones were recarved, like the Tiberian milestone that was reused for Valentinian.82

Distribution of milestone dedications across imperial dynasties and deities.

Despite the relatively low concentrations of Julio-Claudian milestones in the region, they have instigated a new local practice. As epigraphy was introduced in the region at this late stage, the epigraphic habit still had to develop. With the Julio-Claudian milestones signalling the recent reorganizations, the epigraphic landscape was relatively dense with milestones. This might have given the message to the local communities that milestones were an important part of the epigraphic habit. In other regions, where milestones were already present in the Republican period, and possibly less prominent, these may not have seemed that important, resulting in an over-representation of milestones in this north-western part of the Iberian Peninsula.

Moreover, when turning to the texts of these milestones, we observe an interesting phenomenon: the case in which the Emperor is mentioned changes. The Julio-Claudian milestones have the Emperor in the nominative case, giving him the lead in setting up the stone.83 This supports the idea of the Emperors showing their power as actors reorganizing the landscape. However, during the Antonine dynasty, we observe a shift towards the dative case. In other words, the stone is given to the Emperor. The explanation for this might be a shift in agency: in the earlier stages the Emperor, or more likely imperial actors, set up the milestones in the name of the imperator, whereas in the later period local communities took up the maintenance of the roads. As customary, the inscriptions still started with the name of the Emperor; however, the dative was chosen to indicate it was set up for, not by, him. This shift in case made the milestones follow the case of honorific inscriptions.84 In addition, these honorific milestones left out the distance, indicating that their function as milestones had become secondary.

4.6 Conclusions

The current chapter has shown the possibilities we have for studying Latinization on the Iberian Peninsula using GIS. Despite substantial methodological challenges, broad patterns can be drawn. Even though the methods of data curation mean that the urban factor is overestimated in the data set, the epigraphic habit of the Iberian Peninsula is undoubtedly overwhelmingly urban. The urban element in the spread of Latin and the uptake of the epigraphic habit has long been appreciated, but in this analysis we combined a cleaner than ever before epigraphic data set and new data on self-governing communities to explore the distribution by conventus and whether patterns can be established between different statuses of community. We can observe that the conventus with higher urban densities and the communities with pre-Flavian promotions (those receiving the status of colonia or municipium civium Romanorum) were more likely to engage in the epigraphic habit. These Roman citizen communities were promoted relatively early under Caesar or Augustus and often received coloni or already had a relationship with Rome. This small set of communities, only 16 per cent, produce one-third of the epigraphic-habit inscriptions. Unsurprisingly, they show a similar distribution of epigraphic-habit output, focusing mostly on funerary and honorific epigraphy. This high uptake was explained through various means: they are over-represented in research; they tend to have larger cities and populations; they were centres of power for the elite; and they were more likely to engage in intercity rivalry, underscoring their importance and seniority.

Nonetheless, we observe that the communities promoted to Latin municipia with the grant of ius Latii under the Flavians did engage in the epigraphic habit, following the Roman communities. Interestingly, in these communities the epigraphic-habit output tended to focus more on religious epigraphy. This is explained in part via the relative distribution, as these were less likely to engage in honorific epigraphy and housed smaller populations. However, the proportion of religious epigraphic output becomes even stronger within the communities without a known status and the epigraphy beyond the reach of urban centres. This can be explained partly through the presence of supra-regional sanctuaries that contain great concentrations of votive epigraphy. Future research should investigate the role of religious epigraphy and the nature, whether it is focused on local or Roman deities, within the various communities.

The materiality of epigraphic output showed rather unsurprising patterns. Communities were most likely to use local materials; we see that the distribution of the use of granite and limestone follows the geological spread of these materials. Similarly, the use of marble for epigraphic output tends to be located around the marble quarries in the south-west of the peninsula. Interestingly, this valuable material, here a local product, can be used in the same manner as granite and limestone in these areas. Nonetheless, we observe a preference for marble within the epigraphic output of the coloniae, which can be linked to these communities receiving coloni and therefore people already familiar with the ‘Roman lifestyle’, and imported marble is clearly a feature for the highest-status displays.

Future research should focus on a closer exploration of the intersection of material, object type, text type, the status of the individuals involved, and, above all, geographical precision. The current geographical data have already been significantly improved through the work of the LatinNow project, and that makes differentiations between urban types and urban and rural settings possible. If we were to enhance the epigraphic data set further, we could start to explore in finer detail and to trace more specific places of display on the level of the civitas and over time. However, the improvement of data is not as straightforward as we might think at first sight. In order to improve the spatial data, we need to collect precise geo-coordinates. Within the ATLAS project, the epigraphy from a small number of urban centres has been collected on the building level, allowing the observation of the changes within the city and the differentiation of the epigraphic output of the various late antique basilicae of Carthago.85 Besides collecting the find-spots, we should be cautious about the possibility of secondary locations, owing to reuse. Future projects should consider methods to indicate the certainty as to whether a find-spot is primary or secondary. When we have data of such precision, we can start analysing geospatial patterns within communities and come to a greater understanding of the epigraphic landscape. In addition, we are once again confronted with the issue of dating. In order to allow for the study of chronological patterns in a similar manner as with the spatial patterns, we need to have machine-readable dates. Moreover, databases allow for adding certainty to dates, so we can differentiate between certain dating obtained through, for example, precise stated regnal dates, on the one hand, and less certain dating methods such as formulae, palaeography, and iconography, on the other.

As this chapter has shown, the current curated epigraphic data set in combination with settlement data allows us to analyse the epigraphic output and observe patterns, particularly on the macro-scale. With the LatinNow data set, we can undertake similar analyses within and between other regions across the West, using a variety of archaeological and social data, exposing regionalities. Even without the further curation of the data, we can already gain insights into the epigraphic output and Latinization of the varied provincial communities at a scale not previously possible.

Footnotes

This output has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme, grant agreement No. 715626 (LatinNow). This contribution was not possible without the enormous patience of the editors, who have allowed me to work on the chapter up to the last moment. Moreover, their discussions and suggestions aided in streamlining my thoughts and the text. I want to thank all the participants of the LatinNow workshop that took place in 2022, where we discussed a first draft of this chapter. Lastly, I thank my wife Simone who put up with me finishing this chapter soon after our lovely daughter Kyra was born.

De Hoz (2022), 37.

Hopkins (1980); Corbier (1991), 228.

See Houten (2023a) for these factors and further references.

Houten (2021), 53.

The EAGLE export had records from the online epigraphic resources up to c.2017, but these were subsequently added to by the team with updated data and records from, for example, Hesperia, EDH, and RIBOnline. However, these more recently added records did not, for the most part, pertain to the Latin inscriptional record of the Iberian Peninsula.

Hispania Epigraphica the journal and Hispania Epigraphica Online have no direct relation to one another. To avoid confusion I will refer to the database as Hispania Epigraphica Online or HEpOnl.

Houten (2022c), 76.

Strabo mentions it as the largest city in the west (3.1.8 and 3.5.3).

Abascal Palazón and Cebrián Fernández (2007); Cebrián Fernández (2020); Abascal Palazón, Alföldy, and Cebrián Fernández (2011). For the online database of Roman inscriptions from Segobriga, see https://www.ua.es/personal/juan.abascal/Segobriga_imagenes_65.html.

Alarcão and Étienne (1976). HEpOnl holds 510 records from this publication.

The search was not available across Portuguese language materials at the time of the research. But the focus on the difference in volume of Spanish-language outputs reinforces the claim for wider interest in Segobriga and Conimbriga. An Ngram of the English-language scholarship also shows Ercavica and Aeminium at the bottom of the Ngram.

CIL II 3.

HEp 1, p. 13.

HEpOnl gives Grândola as the location—its coordinates were associated with the epigraphy —whereas IRCP (d’Encarnação 1984: 276–92) gives Tróia, Melides, Grândola, following the journal’s format of place, freguesía, municipality.

Houten (2021), 236.

One of the student assistants recorded surprise in the margins of a document: ‘It makes no sense that there is no date for this inscription in CILA, there is a clear date in the inscription.’ See CILA II 150. The inscription can be dated to 17 January 544 as it reads: XVI Kal(en)das Febru(arias)/(a)era DLXXXII.

For a more extensive discussion on the issues of dating, see Houten et al. (forthcoming).

Raepsaet-Charlier (2002). The abbreviated forms start in the beginning of the second century.

Carroll (2006), 268.

Schwarz (2004b), 109.

Beltrán Lloris (2015b), 132.

Melchor Gil (2017), 44.

For the role cities played in the spread and use of Latin, see Houten (2023a).

Houten (2021), 50–1.

Gell. NA 16.13.4–5.

For further details, see Houten (2021), 71–129.

Houten (2021), 94; (2017; 2020).

Houten (2021), 71–129.

Houten (2021), 226.

CIL II 4244.

On the relationship between municipium Latinum and the Quirina tribus, see Andreu Pintado (2004a; 2004b).

Haynes (2013), 32; Adams (2003a), 281.

Plin. HN 3.24.

Galsterer (1971), 11; see Moncunill (2017), 13, on the naming practice.

Galsterer (1971), 11; see also García Fernández (2011), 51–2.

Barrandon (2011), 62.

Cooley (2012), 170; Crawford (1996), no. 37.

Houten (2023a), 72–3.

Syme (1981), 273.

It is interesting to place these next to the slightly higher estimations of other scholars: ‘Latin epitaphs are thought to amount to at least 75 percent’ (Beltrán Lloris 2015a, 95); ‘between two thirds and three quarters are epitaphs’ (Chioffi 2014, 627); ‘epitaphs account for perhaps two-thirds of all surviving Greek and Latin inscriptions’ (Bodel 2001, 30).

Plin. HN 34.17; Melchor Gil (2017), 44.

Houten (2023a), 74.

Smith and Ward-Perkins (2016), 65; Leone (2016), 251; Abascal Palazón, Alföldy, and Cebrián Fernández (2011). See also Houten (forthcoming) on the interaction between the population and the statues.

AE 2001, 1246. Proculus is the most logical name based on the prevalence of this name in this period in Hispania; see Abascal Palazón, Alföldy, and Cebrián Fernández (2001), 119 (also for the dating).

Navarro, Gorrochategui, and Vallejo (2011), 132; Simón and Jordán (2018), 188; Abascal Palazón, Cebrián Fernández, and Trunk (2014), 51. The name Spantamicus is also found in a funerary inscription from Segobriga; see Abascal Palazón, Alföldy, and Cebrián Fernández (2009).

Veyne (1976); Zanker (2000), 39; Tak (1990), 90; Syme (1981), 270.

Houten (2021), 254.

D’Encarnação (1984), 561–629 (no. 482–565); Guerra et al. (2003); Schattner, Suárez Otero, and Koch (2014); Schattner, Guerra, and Fabião (2005); Schattner and Suárez Otero (2020). See Schattner (2013) for a complete overview of the extra-regional sanctuaries.

LatinNow database. Note that these are attributed to the actual site at São Miguel da Mota (14) and the municipality Terena (74), owing to the issues of attribution mentioned above. Note there are several more, but, because of their fragmentary nature, these cannot with certainty be assigned as religious inscriptions.

Richert (2012), 39.

Guerra et al. (2003), 433.

There appears to be no clear correlation between stone type and text type, but, since many of our stone types are not recorded, further data enhancement is required before firm conclusions can be reached.

Taelman (2022), 852; (2014). Taelman (2014) shows even Ammaia near the Estremoz/Vila Viçosa mines used imported marble from Teos (Turkey) and Skyros (Greece) for decoration.

D’Encarnação (1984), 561–629.

Houten (2021), 197; (2023a), 42; (2023b), 72.

Taelman (2022), 863.

Richardson (1986); Arce (1982), 43–69.

Ozcáriz Gil (2008), 90.

Alföldy (1987), 110.

For these urban densities, see Houten (2021).

España (2022), 96.

Campedelli (2022), 127.

España (2022), 98.

Gil Mantas (2022), 223.

See Rodríguez Colmenero, Ferrer Sierra, and Álvarez Asorey (2004). Interestingly the milestones to Titus and Domitian use the ablative case, as can be seen in the use of Caesare.

For more information, see ATLAS-cities.com.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| November 2024 | 11 |

| December 2024 | 23 |

| January 2025 | 23 |

| February 2025 | 34 |

| March 2025 | 17 |

| April 2025 | 16 |

| May 2025 | 8 |