-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Laura M Welti, Kristen M Beavers, Annie Mampieri, Stephen R Rapp, Edward Ip, Sally A Shumaker, Daniel P Beavers, Patterns of Home Environmental Modification Use and Functional Health: The Women’s Health Initiative, The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, Volume 75, Issue 11, November 2020, Pages 2119–2124, https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glz290

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We examined common patterns of home environmental modification (HEM) use and associated major (including disability-, cardiovascular-, and cancer-related) health conditions and events among older women.

Women, aged 78.6 ± 6.3 years (n = 71,257), self-reported utilization of nine types of HEMs (hand rails, grab bars, ramps, nonslip surfaces, tacking carpets/rugs, decreasing clutter, increasing lighting, raised sink/counter heights, other). Concurrent history of major health conditions and events was collected. Odds ratios (ORs) were estimated based on overall HEM use and four latent classes (low HEM use [56%], rails/grab bars [20%], lighting/decluttering [18%], high HEM use [5%]), adjusted for age, marital status, race/ethnicity, education, depression, and obesity.

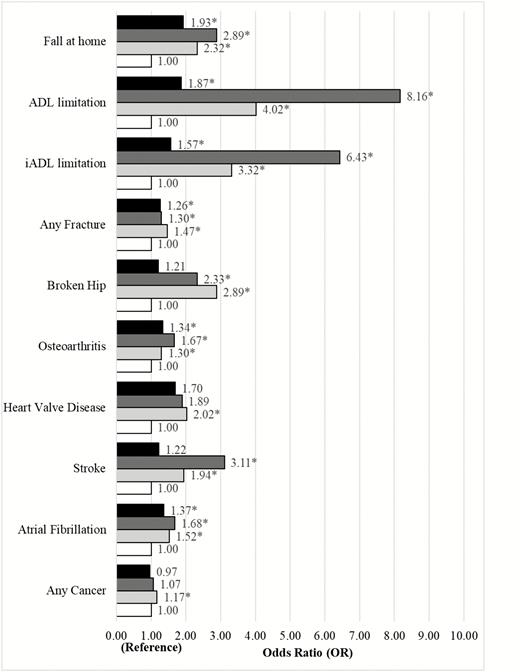

Fifty-five percent of women reported using any HEM (overall), with strongest associations among disability-related conditions. Activities of daily living limitations were strongly associated with high HEM use (OR = 8.16, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 6.62–10.05), railing/grab bar use (OR = 4.02, 95% CI = 3.26–4.95), and lighting/declutter use (OR = 1.87, 95% CI = 1.40–2.50) versus low HEM use. Recent falls were positively associated with overall HEM use (OR = 1.79, 95% CI = 1.72–1.87); high HEM use (OR = 2.89, 95% CI = 2.64–3.16), railings/grab bars use (OR = 2.32, 95% CI = 2.18–2.48), and lighting/declutter use (OR = 1.93, 95% CI = 1.79–2.08) were positively associated with recent falls. Modest associations were observed between HEM use and select (ie, atrial fibrillation, heart valve disease, stroke) cardiovascular outcomes.

Among older women, disability-related conditions, including functional limitations and recent falls, were strongly associated with overall HEM use, high HEM use, and railings/grab bar use.

Older adults overwhelmingly prefer to remain in their current homes for as long as possible (1). However, age-related and disease-related increases in functional limitations (such as difficulties with walking, carrying items, or climbing stairs) (2) and fall risk (3,4) interfere with prolonged ability to age in place. This observation is particularly relevant for older women, who are living the longest with reduced function (5–7).

Home environmental modifications (HEMs), such as the addition of/changes to: railings, grab bars, nonslip surfaces, shower or toilet seat, and lighting (8), can help older adults maintain independent living by improving performance of activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental (IADLs) (9–14) and reducing risk of falls and injury (15–18). According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, approximately 42% of older adults report using HEMs, with rates slightly higher among women and those 75 years and older (9). Despite their prevalence, limited research has examined the health-related correlates of HEM use. Greater total number of health conditions or major health events are known to be positively associated with overall HEM use (19–22); however, specific health conditions and events associated with common patterns of HEM use, that is, individual strategies that frequently are used together such as increasing lighting and decluttering, among older adults is unknown. Identifying associations between major health-related correlates and specific patterns of HEM usage would add to the current literature and potentially inform future intervention strategies aimed at promoting independent living among older adults, and in particular, women.

Building on our prior research identifying latent classes of HEM use, this study aims to advance current understanding of the health conditions or major health events associated with common patterns of HEM use utilizing the well characterized Women’s Health Initiative study (23,24), containing more than 70,000 women with demographic, HEM, chronic disease, and disability data. We hypothesize that patterns of HEM use will be differentially associated with chronic disease and disability, with the strongest associations observed for disability-related conditions.

Method

Women’s Health Initiative

The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) is a large, multicenter clinical trial (CT), and observational study (OS) examining the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in postmenopausal women. 161,808 women were recruited from 40 U.S. clinic centers from 1993 to 1998 (aged 50–79 years old). Full details can be found in the published recruitment and methods (23) and design (24) papers. In 2005, participants were invited to continue in the study for 5 years of follow-up (Extension 1). In 2010, participants were invited to continue for an additional 5 years (Extension 2), which enrolled 93,500 consenting participants followed through 2015. WHI protocol and consent forms were approved by local institutional review boards before use.

Current Study Sample

Our initial sample included 88,500 women enrolled in Year 3 of Extension 2 (2013–2014). From this, 81,420 women (92%) responded to an annual mailed survey with current demographic characteristics, health conditions, or major health events of interest (listed below). A separate supplemental questionnaire containing HEMs use data was collected from 90% of respondents (n = 79,650). The final analysis sample for this study included 71,257 women with concurrent HEMs data and demographic characteristics, health conditions, or major health events of interest.

Latent HEM Classifications

In the supplemental questionnaire, participants were asked to mark changes or additions they made to their home for themselves or someone else, including: railings or banisters, grab bars, indoor or outdoor ramps, nonslip surfaces, tacking down carpets/rugs, decreasing clutter, increasing lighting, sink/counter heights, other, or no changes. These items were adapted from the Rebuilding Together Safe at Home Checklist, created in partnership with the Administration on Aging and the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) (25,26). The three most commonly reported individual HEM strategies were grab bars (31%), decreasing clutter (26%), and increasing lighting (18%). Based on responses to this questionnaire, four latent classes of commonly reported patterns of HEM usage were identified, and are briefly described below.

The “low HEM use” latent class grouped the HEM users with the lowest probability of utilizing any individual HEM strategy (56%). The second latent class, “railings/grab bars,” grouped those who had a high likelihood of using hand rails and grab bars and low probability of using the other HEM strategies (21%). A third class, “lighting/declutter,” describes women who commonly reported increasing lighting and decluttering the home, but had lower probability of using the other HEM strategies (18%). Finally, the smallest latent class, “high HEM use,” reported high utilization of many HEM strategies (5%). These four latent HEM classes (low HEM use, railings/grab bars, lighting/decluttering, high HEM use) characterize common patterns of HEM use within this cohort of older women.

Participant Demographic and Health Information

Demographic and lifestyle characteristics were collected at WHI baseline and on the annual surveys, including: current age at time of questionnaire (<75 years, ≥75 years), marital status (married or marriage-like relationship) at WHI baseline, race/ethnicity (black, Hispanic, Caucasian, other), education (high school [HS] or less), current self-reported general health (excellent, very good, good, fair, poor), current depression (Burnam Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale—Short Form (CES-D SF) (27) score ≥ 0.06), and baseline obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2). Self-reported recent history of falls was collected from the questionnaire in which participants responded yes or no to the question, “In the last year, did you fall at home?”

Current overall functional status was derived from four items on the annual survey that assess ADLs (eating, dressing, transferring, bathing) and two items that assess more complex life tasks, IADLs (grocery shopping, taking medications). Each item was self-rated on a scale of 1–3 describing how much help was needed to complete the activities: (1) without help; (2) with some help; (3) unable to complete without help. Responses of 2 or 3 on any component are defined as having an ADL or IADL limitation, respectively.

The following major health conditions and events (current or ever) were assessed on the annual mailed survey and adjudicated (28): history of any fracture, broken hip, osteoarthritis, angina, atrial fibrillation, coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), coronary heart disease (CHD), heart valve disease, myocardial infarction (MI), total MI, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA), stroke, any cancer, and breast cancer. Of interest, six disability-related health conditions or events (falls at home, ADL limitation, IADL limitation, any fracture, broken hip, osteoarthritis), three cardiovascular-related conditions or events (heart valve disease, stroke, atrial fibrillation), and any cancer were examined in our main analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Participant characteristics were summarized overall and by HEM utilization category (Any HEM Use vs No HEM Use) using descriptive characteristics. Unadjusted statistical comparisons between HEM users and nonusers were performed using t-tests for continuous data and chi-square tests for categorical data. The odds of any HEM use were presented for all disability-, cardiovascular-, and cancer-related disease events unadjusted and with adjustment for age, marital status, race/ethnicity, education, depression, and obesity status. Latent class analyses (LCA) were conducted to organize individual observed HEM response patterns into groups. This allows us to identify which individual HEM strategies women commonly combined together, thus forming latent classes of women who share common HEM strategies. We assumed four latent classes based on previous work, and analyses were conducted using the PROC LCA macro in SAS (29). Associations between key health event outcomes (disability-, cardiovascular-, and cancer-related disease events, identified from previous logistic regression as being associated with overall HEM use) and latent HEM classes were estimated using multinomial logistic regression modeling using latent class membership as the response. Models were adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, depression, and obesity status; relationships are presented using odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), with the low HEM use group, women who report little to no HEM utilization, as the referent group. All analyses were conducted using SAS v9.4 and comparisons were deemed statistically significant at a 0.05 level.

Results

Study Sample Characteristics

Of the sample population, 55% of women reported utilizing at least one HEM. Table 1 provides demographic and health characteristics of study participants by HEM usage category (any vs none). Women were an average 78.6 ± 6.3 years old at the time of the supplemental questionnaire, 88.7% were non-Hispanic white, and few had a high school level education or less (17.2%). The proportion of women reporting HEM use was similar across all race/ethnicities. HEM use was frequently reported among women using walk aids (78.3%), recently living in a nursing home (73.6%), and using special services where they live (74.7%). This same trend is shown among women with fair to poor self-rated general health, ADL limitations, and IADL limitations. Lastly, HEM use was more common among women who reported any major health conditions/events (64.7%).

| Characteristic . | Any HEM Use . | No HEM Use . |

|---|---|---|

| Total participants | 39,851 (55.9) | 31,406 (44.1) |

| Age (years) | 79.5 ± 6.3 | 77.4 ± 6.0 |

| Married | 27,015 (56.7) | 20,649 (43.3) |

| HS education or less | 6,424 (52.8) | 5,750 (47.2) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 35,326 (56.0) | 27,788 (44.0) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 880 (51.6) | 824 (48.4) |

| Black/African American | 2,204 (56.4) | 1,702 (43.6) |

| Depression | 2,698 (62.3) | 1,631 (37.7) |

| Obesity | 11,491 (62.2) | 6,992 (37.8) |

| General health | ||

| Good to excellent | 33,720 (54.3) | 28,343 (45.7) |

| Fair to poor | 3,598 (70.9) | 1,476 (29.1) |

| Live in place with special services | 3,057 (59.7) | 2,060 (40.3) |

| Uses special services | 1,140 (74.7) | 387 (25.3) |

| Live in nursing home in past year | 1,150 (73.6) | 413 (26.4) |

| Walk aid use | ||

| Cane | 4,451 (77.3) | 1,308 (22.7) |

| Crutches | 30 (78.9) | 8 (21.1) |

| Walker | 1,968 (80.7) | 470 (19.3) |

| Wheelchair | 281 (77.2) | 83 (22.8) |

| Major health condition/event | ||

| Fall at home in past year | 11,079 (69.0) | 4,971 (31.0) |

| ADL limitation | 1,194 (81.7) | 267 (18.3) |

| IADL limitation | 3,900 (77.7) | 1,118 (22.3) |

| Any fracture | 3,111 (62.2) | 1,888 (37.8) |

| Broken hip | 863 (72.6) | 326 (27.4) |

| Angina | 947 (63.0) | 555 (37.0) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 476 (65.1) | 255 (34.9) |

| CABG | 648 (59.4) | 442 (40.6) |

| Coronary heart disease | 1,177 (63.0) | 691 (37.0) |

| Coronary revascularization | 2,123 (62.2) | 1,288 (37.8) |

| Heart valve disease | 132 (71.4) | 53 (28.6) |

| Myocardial infarction | 1,157 (63.1) | 678 (36.9) |

| Total myocardial infarction | 1,260 (63.4) | 728 (36.6) |

| Osteoarthritis | 19,931 (59.9) | 13,356 (40.1) |

| PTCA | 1,648 (61.8) | 1,017 (38.2) |

| Stroke | 906 (68.9) | 408 (31.1) |

| Any cancer | 6,805 (57.9) | 4,957 (42.1) |

| Breast cancer | 3,504 (56.5) | 2,695 (43.5) |

| Characteristic . | Any HEM Use . | No HEM Use . |

|---|---|---|

| Total participants | 39,851 (55.9) | 31,406 (44.1) |

| Age (years) | 79.5 ± 6.3 | 77.4 ± 6.0 |

| Married | 27,015 (56.7) | 20,649 (43.3) |

| HS education or less | 6,424 (52.8) | 5,750 (47.2) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 35,326 (56.0) | 27,788 (44.0) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 880 (51.6) | 824 (48.4) |

| Black/African American | 2,204 (56.4) | 1,702 (43.6) |

| Depression | 2,698 (62.3) | 1,631 (37.7) |

| Obesity | 11,491 (62.2) | 6,992 (37.8) |

| General health | ||

| Good to excellent | 33,720 (54.3) | 28,343 (45.7) |

| Fair to poor | 3,598 (70.9) | 1,476 (29.1) |

| Live in place with special services | 3,057 (59.7) | 2,060 (40.3) |

| Uses special services | 1,140 (74.7) | 387 (25.3) |

| Live in nursing home in past year | 1,150 (73.6) | 413 (26.4) |

| Walk aid use | ||

| Cane | 4,451 (77.3) | 1,308 (22.7) |

| Crutches | 30 (78.9) | 8 (21.1) |

| Walker | 1,968 (80.7) | 470 (19.3) |

| Wheelchair | 281 (77.2) | 83 (22.8) |

| Major health condition/event | ||

| Fall at home in past year | 11,079 (69.0) | 4,971 (31.0) |

| ADL limitation | 1,194 (81.7) | 267 (18.3) |

| IADL limitation | 3,900 (77.7) | 1,118 (22.3) |

| Any fracture | 3,111 (62.2) | 1,888 (37.8) |

| Broken hip | 863 (72.6) | 326 (27.4) |

| Angina | 947 (63.0) | 555 (37.0) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 476 (65.1) | 255 (34.9) |

| CABG | 648 (59.4) | 442 (40.6) |

| Coronary heart disease | 1,177 (63.0) | 691 (37.0) |

| Coronary revascularization | 2,123 (62.2) | 1,288 (37.8) |

| Heart valve disease | 132 (71.4) | 53 (28.6) |

| Myocardial infarction | 1,157 (63.1) | 678 (36.9) |

| Total myocardial infarction | 1,260 (63.4) | 728 (36.6) |

| Osteoarthritis | 19,931 (59.9) | 13,356 (40.1) |

| PTCA | 1,648 (61.8) | 1,017 (38.2) |

| Stroke | 906 (68.9) | 408 (31.1) |

| Any cancer | 6,805 (57.9) | 4,957 (42.1) |

| Breast cancer | 3,504 (56.5) | 2,695 (43.5) |

Notes: Data are presented as N (%) by row, otherwise mean ± standard deviation. HS = high school; ADL = activities of daily living; IADLs = instrumental activities of daily living; CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; PCTA = percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty.

| Characteristic . | Any HEM Use . | No HEM Use . |

|---|---|---|

| Total participants | 39,851 (55.9) | 31,406 (44.1) |

| Age (years) | 79.5 ± 6.3 | 77.4 ± 6.0 |

| Married | 27,015 (56.7) | 20,649 (43.3) |

| HS education or less | 6,424 (52.8) | 5,750 (47.2) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 35,326 (56.0) | 27,788 (44.0) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 880 (51.6) | 824 (48.4) |

| Black/African American | 2,204 (56.4) | 1,702 (43.6) |

| Depression | 2,698 (62.3) | 1,631 (37.7) |

| Obesity | 11,491 (62.2) | 6,992 (37.8) |

| General health | ||

| Good to excellent | 33,720 (54.3) | 28,343 (45.7) |

| Fair to poor | 3,598 (70.9) | 1,476 (29.1) |

| Live in place with special services | 3,057 (59.7) | 2,060 (40.3) |

| Uses special services | 1,140 (74.7) | 387 (25.3) |

| Live in nursing home in past year | 1,150 (73.6) | 413 (26.4) |

| Walk aid use | ||

| Cane | 4,451 (77.3) | 1,308 (22.7) |

| Crutches | 30 (78.9) | 8 (21.1) |

| Walker | 1,968 (80.7) | 470 (19.3) |

| Wheelchair | 281 (77.2) | 83 (22.8) |

| Major health condition/event | ||

| Fall at home in past year | 11,079 (69.0) | 4,971 (31.0) |

| ADL limitation | 1,194 (81.7) | 267 (18.3) |

| IADL limitation | 3,900 (77.7) | 1,118 (22.3) |

| Any fracture | 3,111 (62.2) | 1,888 (37.8) |

| Broken hip | 863 (72.6) | 326 (27.4) |

| Angina | 947 (63.0) | 555 (37.0) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 476 (65.1) | 255 (34.9) |

| CABG | 648 (59.4) | 442 (40.6) |

| Coronary heart disease | 1,177 (63.0) | 691 (37.0) |

| Coronary revascularization | 2,123 (62.2) | 1,288 (37.8) |

| Heart valve disease | 132 (71.4) | 53 (28.6) |

| Myocardial infarction | 1,157 (63.1) | 678 (36.9) |

| Total myocardial infarction | 1,260 (63.4) | 728 (36.6) |

| Osteoarthritis | 19,931 (59.9) | 13,356 (40.1) |

| PTCA | 1,648 (61.8) | 1,017 (38.2) |

| Stroke | 906 (68.9) | 408 (31.1) |

| Any cancer | 6,805 (57.9) | 4,957 (42.1) |

| Breast cancer | 3,504 (56.5) | 2,695 (43.5) |

| Characteristic . | Any HEM Use . | No HEM Use . |

|---|---|---|

| Total participants | 39,851 (55.9) | 31,406 (44.1) |

| Age (years) | 79.5 ± 6.3 | 77.4 ± 6.0 |

| Married | 27,015 (56.7) | 20,649 (43.3) |

| HS education or less | 6,424 (52.8) | 5,750 (47.2) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 35,326 (56.0) | 27,788 (44.0) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 880 (51.6) | 824 (48.4) |

| Black/African American | 2,204 (56.4) | 1,702 (43.6) |

| Depression | 2,698 (62.3) | 1,631 (37.7) |

| Obesity | 11,491 (62.2) | 6,992 (37.8) |

| General health | ||

| Good to excellent | 33,720 (54.3) | 28,343 (45.7) |

| Fair to poor | 3,598 (70.9) | 1,476 (29.1) |

| Live in place with special services | 3,057 (59.7) | 2,060 (40.3) |

| Uses special services | 1,140 (74.7) | 387 (25.3) |

| Live in nursing home in past year | 1,150 (73.6) | 413 (26.4) |

| Walk aid use | ||

| Cane | 4,451 (77.3) | 1,308 (22.7) |

| Crutches | 30 (78.9) | 8 (21.1) |

| Walker | 1,968 (80.7) | 470 (19.3) |

| Wheelchair | 281 (77.2) | 83 (22.8) |

| Major health condition/event | ||

| Fall at home in past year | 11,079 (69.0) | 4,971 (31.0) |

| ADL limitation | 1,194 (81.7) | 267 (18.3) |

| IADL limitation | 3,900 (77.7) | 1,118 (22.3) |

| Any fracture | 3,111 (62.2) | 1,888 (37.8) |

| Broken hip | 863 (72.6) | 326 (27.4) |

| Angina | 947 (63.0) | 555 (37.0) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 476 (65.1) | 255 (34.9) |

| CABG | 648 (59.4) | 442 (40.6) |

| Coronary heart disease | 1,177 (63.0) | 691 (37.0) |

| Coronary revascularization | 2,123 (62.2) | 1,288 (37.8) |

| Heart valve disease | 132 (71.4) | 53 (28.6) |

| Myocardial infarction | 1,157 (63.1) | 678 (36.9) |

| Total myocardial infarction | 1,260 (63.4) | 728 (36.6) |

| Osteoarthritis | 19,931 (59.9) | 13,356 (40.1) |

| PTCA | 1,648 (61.8) | 1,017 (38.2) |

| Stroke | 906 (68.9) | 408 (31.1) |

| Any cancer | 6,805 (57.9) | 4,957 (42.1) |

| Breast cancer | 3,504 (56.5) | 2,695 (43.5) |

Notes: Data are presented as N (%) by row, otherwise mean ± standard deviation. HS = high school; ADL = activities of daily living; IADLs = instrumental activities of daily living; CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; PCTA = percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty.

Overall and Individual HEM Use Associations by Major Health Conditions and Events

Unadjusted and adjusted associations between major health conditions/events and overall HEM use (any vs none) can be found in Table 2. Unsurprisingly, women who reported disability-related conditions/events had significantly greater odds of HEM use compared who did not report those conditions, while strongest associations were found among women who reported ADL (OR: 3.60, 95% CI: 3.15–4.12) or IADL limitations (OR: 2.94, 95% CI: 2.75–3.15). After model-adjustment, all disability-related health conditions/events remained significantly associated with any HEM use. Of cardiovascular- and cancer-related health conditions/events, only atrial fibrillation, heart valve disease, and stroke were positively associated with HEM use after model-adjustment.

Unadjusted and Model-Adjusted Associations Between Any HEM Use and Major Health Conditions and Events, by Category

| . | Any HEM Use Vs No HEM Use . | |

|---|---|---|

| Major Health Condition or Event . | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) . | Model-Adjusted OR (95% CI) . |

| Disability-related | ||

| Fall at home in past year | 2.06 (1.98–2.14) | 1.79 (1.72–1.87) |

| ADL limitation | 3.60 (3.15–4.12) | 2.48 (2.13–2.88) |

| IADL limitation | 2.94 (2.75–3.15) | 2.09 (1.93–2.25) |

| Any fracture | 1.32 (1.25–1.40) | 1.23 (1.15–1.31) |

| Broken hip | 2.11 (1.85–2.40) | 1.74 (1.52–2.01) |

| Osteoarthritis | 1.35 (1.31–1.39) | 1.22 (1.18–1.26) |

| Cardiovascular-related | ||

| Angina | 1.35 (1.22–1.50) | 1.07 (0.95–1.20) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.48 (1.27–1.72) | 1.27 (1.07–1.50) |

| CABG | 1.45 (1.27–1.65) | 1.08 (0.93–1.25) |

| Coronary heart disease | 1.35 (1.23–1.49) | 1.08 (0.97–1.20) |

| Coronary revascularization | 1.32 (1.23–1.41) | 1.04 (0.96–1.13) |

| Heart valve disease | 1.97 (1.43–2.70) | 1.68 (1.18–2.41) |

| Myocardial infarction | 1.36 (1.23–1.49) | 1.07 (0.97–1.20) |

| Total myocardial infarction | 1.38 (1.25–1.51) | 1.09 (0.98–1.21) |

| PTCA | 1.29 (1.19–1.40) | 1.04 (0.95–1.14) |

| Stroke | 1.77 (1.57–1.99) | 1.48 (1.29–1.69) |

| Cancer-related | ||

| Any cancer | 1.10 (1.06–1.14) | 1.02 (0.97–1.06) |

| Breast cancer | 1.03 (0.97–1.08) | 0.97 (0.92–1.03) |

| . | Any HEM Use Vs No HEM Use . | |

|---|---|---|

| Major Health Condition or Event . | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) . | Model-Adjusted OR (95% CI) . |

| Disability-related | ||

| Fall at home in past year | 2.06 (1.98–2.14) | 1.79 (1.72–1.87) |

| ADL limitation | 3.60 (3.15–4.12) | 2.48 (2.13–2.88) |

| IADL limitation | 2.94 (2.75–3.15) | 2.09 (1.93–2.25) |

| Any fracture | 1.32 (1.25–1.40) | 1.23 (1.15–1.31) |

| Broken hip | 2.11 (1.85–2.40) | 1.74 (1.52–2.01) |

| Osteoarthritis | 1.35 (1.31–1.39) | 1.22 (1.18–1.26) |

| Cardiovascular-related | ||

| Angina | 1.35 (1.22–1.50) | 1.07 (0.95–1.20) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.48 (1.27–1.72) | 1.27 (1.07–1.50) |

| CABG | 1.45 (1.27–1.65) | 1.08 (0.93–1.25) |

| Coronary heart disease | 1.35 (1.23–1.49) | 1.08 (0.97–1.20) |

| Coronary revascularization | 1.32 (1.23–1.41) | 1.04 (0.96–1.13) |

| Heart valve disease | 1.97 (1.43–2.70) | 1.68 (1.18–2.41) |

| Myocardial infarction | 1.36 (1.23–1.49) | 1.07 (0.97–1.20) |

| Total myocardial infarction | 1.38 (1.25–1.51) | 1.09 (0.98–1.21) |

| PTCA | 1.29 (1.19–1.40) | 1.04 (0.95–1.14) |

| Stroke | 1.77 (1.57–1.99) | 1.48 (1.29–1.69) |

| Cancer-related | ||

| Any cancer | 1.10 (1.06–1.14) | 1.02 (0.97–1.06) |

| Breast cancer | 1.03 (0.97–1.08) | 0.97 (0.92–1.03) |

Notes: Data are presented as N (%), otherwise mean ± standard deviation. Model adjustments include age, marital status, race/ethnicity, education, depression, and obesity status. ADL = activities of daily living; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living; CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; PCTA = percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty.

Unadjusted and Model-Adjusted Associations Between Any HEM Use and Major Health Conditions and Events, by Category

| . | Any HEM Use Vs No HEM Use . | |

|---|---|---|

| Major Health Condition or Event . | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) . | Model-Adjusted OR (95% CI) . |

| Disability-related | ||

| Fall at home in past year | 2.06 (1.98–2.14) | 1.79 (1.72–1.87) |

| ADL limitation | 3.60 (3.15–4.12) | 2.48 (2.13–2.88) |

| IADL limitation | 2.94 (2.75–3.15) | 2.09 (1.93–2.25) |

| Any fracture | 1.32 (1.25–1.40) | 1.23 (1.15–1.31) |

| Broken hip | 2.11 (1.85–2.40) | 1.74 (1.52–2.01) |

| Osteoarthritis | 1.35 (1.31–1.39) | 1.22 (1.18–1.26) |

| Cardiovascular-related | ||

| Angina | 1.35 (1.22–1.50) | 1.07 (0.95–1.20) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.48 (1.27–1.72) | 1.27 (1.07–1.50) |

| CABG | 1.45 (1.27–1.65) | 1.08 (0.93–1.25) |

| Coronary heart disease | 1.35 (1.23–1.49) | 1.08 (0.97–1.20) |

| Coronary revascularization | 1.32 (1.23–1.41) | 1.04 (0.96–1.13) |

| Heart valve disease | 1.97 (1.43–2.70) | 1.68 (1.18–2.41) |

| Myocardial infarction | 1.36 (1.23–1.49) | 1.07 (0.97–1.20) |

| Total myocardial infarction | 1.38 (1.25–1.51) | 1.09 (0.98–1.21) |

| PTCA | 1.29 (1.19–1.40) | 1.04 (0.95–1.14) |

| Stroke | 1.77 (1.57–1.99) | 1.48 (1.29–1.69) |

| Cancer-related | ||

| Any cancer | 1.10 (1.06–1.14) | 1.02 (0.97–1.06) |

| Breast cancer | 1.03 (0.97–1.08) | 0.97 (0.92–1.03) |

| . | Any HEM Use Vs No HEM Use . | |

|---|---|---|

| Major Health Condition or Event . | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) . | Model-Adjusted OR (95% CI) . |

| Disability-related | ||

| Fall at home in past year | 2.06 (1.98–2.14) | 1.79 (1.72–1.87) |

| ADL limitation | 3.60 (3.15–4.12) | 2.48 (2.13–2.88) |

| IADL limitation | 2.94 (2.75–3.15) | 2.09 (1.93–2.25) |

| Any fracture | 1.32 (1.25–1.40) | 1.23 (1.15–1.31) |

| Broken hip | 2.11 (1.85–2.40) | 1.74 (1.52–2.01) |

| Osteoarthritis | 1.35 (1.31–1.39) | 1.22 (1.18–1.26) |

| Cardiovascular-related | ||

| Angina | 1.35 (1.22–1.50) | 1.07 (0.95–1.20) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.48 (1.27–1.72) | 1.27 (1.07–1.50) |

| CABG | 1.45 (1.27–1.65) | 1.08 (0.93–1.25) |

| Coronary heart disease | 1.35 (1.23–1.49) | 1.08 (0.97–1.20) |

| Coronary revascularization | 1.32 (1.23–1.41) | 1.04 (0.96–1.13) |

| Heart valve disease | 1.97 (1.43–2.70) | 1.68 (1.18–2.41) |

| Myocardial infarction | 1.36 (1.23–1.49) | 1.07 (0.97–1.20) |

| Total myocardial infarction | 1.38 (1.25–1.51) | 1.09 (0.98–1.21) |

| PTCA | 1.29 (1.19–1.40) | 1.04 (0.95–1.14) |

| Stroke | 1.77 (1.57–1.99) | 1.48 (1.29–1.69) |

| Cancer-related | ||

| Any cancer | 1.10 (1.06–1.14) | 1.02 (0.97–1.06) |

| Breast cancer | 1.03 (0.97–1.08) | 0.97 (0.92–1.03) |

Notes: Data are presented as N (%), otherwise mean ± standard deviation. Model adjustments include age, marital status, race/ethnicity, education, depression, and obesity status. ADL = activities of daily living; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living; CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; PCTA = percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty.

Unadjusted associations between health conditions/events and individual HEM strategies can be found in Supplementary Table S1. Disability-related health conditions/events increased odds of using any given individual HEM strategy, with the strongest association between ADL limitations and ramps usage (OR: 5.34, 95% CI: 4.67–6.12) compared with women with no limitations. Women who reported heart valve disease showed 1.5–2 times greater odds of using the railings, grab bars, or decluttering, compared with women without the condition; however, stroke was the only cardiovascular-related health condition/event in which a significant association existed across all individual HEM strategies. Lastly, cancer-related conditions were most commonly associated with grab bar usage.

Associations Between Latent HEM Classes and Health Conditions and Events

Model-adjusted associations between latent HEM classes and specific major health conditions or events are presented in Figure 1. All analyses use the low HEM use latent class as the referent group. Overall, railings/grab bars use was the only latent class with significantly higher odds of all health conditions/events. The strongest associations were among both railings/grab bars use and high HEM use and ADL (OR: 4.02, 95% CI: 3.26–4.95; OR: 8.16, 95% CI: 6.62–10.05) and IADL limitations (OR: 6.43, 95% CI: 5.70–7.26; OR: 3.32, 95% CI: 2.98–3.70), respectively.

Latent class models: model-adjusted odds ratios between latent HEM classes and health conditions/events. Note. ADL, activities of daily living; IADL, instrumental activity of daily living. Adjustments: age, marital status, race/ethnicity, education, depression, and obesity status. Lighting/declutter = black; high HEM use = dark gray; railing/grab bars = light gray; low HEM use (reference) = white. *p < .05.

Railings/grab bars latent class showed significantly higher odds of past broken hip (OR: 2.89, 95% CI: 2.39–3.50) and falling at home in the past year (OR: 2.32, 95% CI: 2.18–2.48), while odds of any fracture were 1.47 (95% CI: 1.33–1.63) times greater than odds of any fracture in low HEM use. Odds of having any of the cardiovascular-related conditions were two times greater in the railings/grab bars use latent class compared with low HEM use, and odds of any cancer were only slightly increased (OR: 1.17, 95% CI: 1.09–1.26). High HEM use had more than twice the odds of having a recent fall at home (OR: 2.89, 95% CI: 2.64–3.16) and broken hip (OR: 2.33, 95% CI: 1.75–3.11), with only slightly higher odds for any fracture compared with low HEM use. Stroke survivors had substantially elevated odds for high HEM use (OR: 3.11, 95% CI: 2.48–3.90), while odds for atrial fibrillation were moderate (OR: 1.68, 95% CI: 1.17–2.40). Lighting/declutter use was associated with all disability-related health conditions/events, with the exception of broken hip. However, among all cardiovascular- and cancer-related conditions, lighting/declutter use was only significantly associated with atrial fibrillation (OR: 1.37, 95% CI: 1.01–1.86).

Discussion

This study examined major health conditions and events associated with patterns of HEM utilization in a well-characterized cohort of older women. Overall, 55% of older women reported using at least one HEM, which is in general agreement with previously published prevalence rates from the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (9,20), demonstrating greater prevalence among older women versus older men. We observed that women who are older and reported disability-related health conditions/events have much higher odds of utilizing any HEMs, consistent with earlier findings among the general older adult population (9,30) and Medicare recipients (20,22). Moreover, high HEM use and use of railings/grab bars in particular were most strongly associated with ADL/IADL limitations, while lighting/declutter use was most highly associated with recent history of falls, compared with the low HEM use class. Modest associations were observed between overall HEM use and select (ie, atrial fibrillation, heart valve disease, and stroke) cardiovascular outcomes. These results underscore the importance of recognizing common patterns of HEM strategies used among older women with varying health conditions. Identifying these patterns may serve as a useful vehicle for health professionals to optimize client-centered HEM interventions based on current conditions and health history. Patient self-reported use of HEM strategies could help identify recent loss of function or fear of loss of function to practitioners; conversely, functional limitation in the absence of HEMs could indicate the need for OT intervention.

Previous studies demonstrated that a greater total number of health conditions or comorbidities increase odds of HEM use by 1.5 to 2 times compared with those who report none (19–22). Extending this knowledge to specific health conditions and patterns of HEM use, our most robust associations were found between ADL limitations and railings/grab bars or high HEM use classes. Our observed magnitude of association is in general agreement with prior reports (19–22,30), with one study suggesting as much as an eightfold increase in the odds of using a shower or tub seat modification among those with four or more ADL limitations (22). To this, we report that IADL limitations are also consistently associated with individual HEM use, as well as all three multiple HEM use classes, which has not been previously shown. Additionally, our finding of a positive association between history of falls/fracture and overall HEM use align with some prior studies (20,30), but not all (22,30). Only one other study (30), to the best of our knowledge, has examined associations between specific cardiovascular- or cancer-related health conditions/events and HEM use, which reports a negative association between cancer and use of ramps; yet, our study found a small, yet significant, positive association between cancer and railings/grab bars use, adding equipoise to a limited body of knowledge.

The relationship between chronic disease and disability is stronger among older women than men (5,6), especially those aged 75 and older. According to the 2017 Aging in Place Report (31), the most common issues homeowners experienced in their homes were trips or falls resulting in injury and difficulties completing daily tasks. Data presented here suggest that women with functional limitations, stroke, or recent history of falls have likely adopted more intensive home modifications, including installing railings/grab bars or using a broader array of strategies to either help prevent future adverse health events or to preserve or improve functional status by compensating for functional limitations. Additionally, railings/grab bars use was significantly associated with all health conditions/events, illustrating that there may be fewer barriers to implementing these devices, and older adults may be more aware of the benefits of adding railings or grab bars to maintain or improve autonomy, safety, and accessibility in the home. Odds of having had a stroke were tripled in high HEM users, suggesting that having a stroke increases the need for multiple combined HEM strategies. However, given that we cannot directly measure risk, it is possible that adverse health events occurred after HEM utilization. Future work examining longitudinal changes in both HEM use and onset of chronic disease and disability should help clarify the nature of these associations.

This study lays the foundation for future studies to determine which HEM strategies or usage patterns are most effective at helping older adults age in place. Still, a common concern is the process of implementing HEMs. To optimize safety and effectiveness, often a team of specialists (e.g., assessment, financial, installation, instruction) is required to assist in the process of HEM implementation. For example, a recent study found that injury was twice as likely to occur due to a fall in the bathroom compared with a fall in the living room (32), indicating a need for bathroom HEMs to improve safety and autonomy in ADLs. However, factors, such as education, ethnicity, income, supplemental health insurance, social support, and perceived adequacy of income may impact the decision to implement HEMs, regardless of need (20–22). As such, older adults, especially women who are living longer with limited function, or with less social or financial support, are likely at a disadvantage in utilizing HEMs appropriately. There are major implications for scalability in HEM utilization if simple and affordable HEMs (eg, increased lighting and decluttering) demonstrate as much benefit for aging in place as complex modifications (eg, installing a ramp or raising counter heights). Nevertheless, it is clear that strategies which increase safety and accessibility within the home are much less expensive than relocation or institutionalized care (33) and should be implemented to help older women age in place.

Our study may be the first to comprehensively examine the prevalence—and factors associated with—common patterns of HEM use strategies among older women using latent class analyses. The most important strengths of this study are its large number of HEM users and diversity of HEM strategies assessed. Previous studies have examined factors associated with overall HEM use, individual HEM strategies, or were limited in number and scope of HEMs (ie, located only in bathroom). Lastly, we examined several varied health outcomes, and found differential patterns of use which may help health professionals differentiate HEM intervention targets based on health history or condition presented. There are some limitations to consider. First, our study is cross-sectional, which limits our interpretation in regards to temporality. The next logical step will be to examine how HEM use tracks with onset of chronic disease and disability. Second, HEM use data and osteoarthritis presence were self-reported, introducing the possibility of recall bias. Because disease outcomes are adjudicated for incident event, it is possible that some disease recurrence was missed due to the timing of outcome collection with respect to HEM assessment. Although the living arrangements of women remains unclear, we collected information on whether women stayed in a nursing home in the past year; still, many women would have still referred to their actual home when addressing questions regarding HEMs. Further, the survey question asked whether any changes or additions in the home were made not only for the respondent, but possibly for someone else. Lastly, although the WHI is diverse cohort of older women, results may not apply to all older women or older men.

In sum, the findings of this study suggest that functional limitations and a recent history of falls and overall HEM use were common among older women. Moreover, women with ADL/IADL limitations and recent falls were strongly associated with patterns of high HEM use and use of railings/grab bars compared with the class with low utilization of HEMs. These results shed light on the common patterns of HEM strategies used among older women that may assist in optimizing preventative strategies to maintain function, independence, and aging in place. Future research is needed to identify drivers of HEM adoption and intervention targets aimed to increase HEMs usage in women at risk or in the presence of functional limitations, and to explore whether utilizing common HEM patterns are effective for the prevention of distal health outcomes. These steps could help older adults maintain their independence and function, and improve aging in place.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (AG049232 to D.P.B). The WHI program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, NIH, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services through contracts HHSN268201600018C (G.L. Anderson), HHSN268201600001C (J. Wactawski-Wende), HHSN268201600002C (R.D. Jackson), HHSN268201600003C (M.L. Stefanick), HHSN268201600004C (S.A.S).

Acknowledgments

The sponsor played no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, analysis, and preparation of article.

Author Contributions: L.M.W., K.M.B., E.I., S.A.S., and D.P.B. were involved in concept and design of the article; L.M.W., K.M.B., E.I., S.R.R., S.A.S., and D.P.B. were involved in preparation of Methods; L.M.W., K.M.B., A.M., E.I., S.A.S., and D.P.B. were involved in data analysis and interpretation; L.M.W., A.M., K.M.B., E.I., S.R.R., S.A.S., and D.P.B. were involved in the preparation of article.

WHI Investigators Program Office: (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, Maryland) Jacques Rossouw, Shari Ludlam, Joan McGowan, Leslie Ford, and Nancy Geller. Clinical Coordinating Center: (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA) Garnet Anderson, Ross Prentice, Andrea LaCroix, and Charles Kooperberg. Investigators and Academic Centers: (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) JoAnn E. Manson; (MedStar Health Research Institute/Howard University, Washington, DC) Barbara V. Howard; (Stanford Prevention Research Center, Stanford, CA) Marcia L. Stefanick; (The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH) Rebecca Jackson; (University of Arizona, Tucson/Phoenix, AZ) Cynthia A. Thomson; (University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY) Jean Wactawski-Wende; (University of Florida, Gainesville/Jacksonville, FL) Marian Limacher; (University of Iowa, Iowa City/Davenport, IA) Jennifer Robinson; (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA) Lewis Kuller; (Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC) Sally Shumaker; (University of Nevada, Reno, NV) Robert Brunner; (University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN) Karen L. Margolis. Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study: (Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC) Mark Espeland.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

References

- aging

- atrial fibrillation

- obesity

- cerebrovascular accident

- ischemic stroke

- heart valve diseases

- cancer

- activities of daily living

- cardiovascular system

- depressive disorders

- ethnic group

- lighting

- marital status

- disability

- older adult

- women's health initiative

- environmental modification

- hand rails

- wheelchair ramps

- resource utilization groups

- self-report

- latent class analysis