-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Grace S. Shieh, Shurong Zheng, Richard A. Johnson, Yi-Feng Chang, Kunio Shimizu, Chia-Chang Wang, Sen-Lin Tang, Modeling and comparing the organization of circular genomes, Bioinformatics, Volume 27, Issue 7, April 2011, Pages 912–918, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr049

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Motivation: Most prokaryotic genomes are circular with a single chromosome (called circular genomes), which consist of bacteria and archaea. Orthologous genes (abbreviated as orthologs) are genes directly evolved from an ancestor gene, and can be traced through different species in evolution. Shared orthologs between bacterial genomes have been used to measure their genome evolution. Here, organization of circular genomes is analyzed via distributions of shared orthologs between genomes. However, these distributions are often asymmetric and bimodal; to date, there is no joint distribution to model such data. This motivated us to develop a family of bivariate distributions with generalized von Mises marginals (BGVM) and its statistical inference.

Results: A new measure based on circular grade correlation and the fraction of shared orthologs is proposed for association between circular genomes, and a visualization tool developed to depict genome structure similarity. The proposed procedures are applied to eight pairs of prokaryotes separated from domain down to species, and 13 mycoplasma bacteria that are mammalian pathogens belonging to the same genus. We close with remarks on further applications to many features of genomic organization, e.g. shared transcription factor binding sites, between any pair of circular genomes. Thus, the proposed procedures may be applied to identifying conserved chromosome backbones, among others, for genome construction in synthetic biology.

Availability: All codes of the BGVM procedures and 1000+ prokaryotic genomes are available at http://www.stat.sinica.edu.tw/∼gshieh/bgvm.htm.

Contact: [email protected]

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Most of the prokaryotic genomes (1158 out of 1194, NCBI, August 2010) are circular with a single chromosome (called circular genomes henceforth). Orthologous genes (abbreviated as orthologs) are genes directly evolved from an ancestor gene (Tatusov et al., 1997), and can be traced through different species in evolution. The fraction of shared orthologs between two circular genomes was found to be better conserved than the order of genes (Huynen and Bork, 1998), in which the fraction of shared orthologs between genomes was employed to measure genome evolution of nine prokaryotes. Here, our emphasis is on the structure of circular genomes, which, for example, plays an important role in synthetic biology. A review paper in synthetic genomics (Carrera et al., 2009) indicates that genome organization may influence gene expression, which is vital for organisms. Further, predicting or modeling the rules of genome organization via comparative genomics may provide valuable information for genome construction.

We reason that genome structure can be studied via distributions of shared orthologs between genomes, e.g. the most or least favored region in which shared orthologs between each pair of bacterial genomes are located. While the marginal distributions of shared orthologs are often found to be asymmetric and bimodal, to date there is no joint distribution with closed-formed marginals to model such data. This motivated us to develop a family of joint distribution and its related statistical inferences.

Recent studies show that gene order is extensively conserved between closely related species, but rapidly become less conserved among more distantly related species. This trend is likely to be universal in prokaryotes (Tamames, 2001; Wolf et al., 2001). However, the fraction of shared orthologs between two circular genomes is more conserved than the order of genes (see Fig. 6 of Huynen and Bork, 1998). In addition to the fraction of shared orthologs between bacterial genomes, we further incorporate the distributions of shared orthologs of paired circular genomes to infer similarity of their genome organization. By converting the locations of shared orthologs in any paired circular genomes into angles, these pairs of angles can be viewed as bivariate circular vectors.

Most of the marginal distributions of shared orthologs in circular genomes are asymmetric and/or multimodal, which can be modeled by the generalized von Mises distribution (GVM) (Maksimov, 1967; Yfantis and Borgman, 1982). Therefore, we propose a family of bivariate circular distributions with each marginal assuming a GVM distribution, and call this family the bivariate generalized von-Mises (BGVM). The inference procedures, estimation of the parameters in BGVM and testing for independence of structures of paired circular genomes, are developed. A novel correlation measure, which is based on the fraction of shared orthologs and a circular grade correlation derived here, is introduced to measure organization similarity between circular genomes. Furthermore, this similarity is visually depicted by the rose diagrams of shared orthologs.

The marginal distributions of BGVM are quite flexible since GVM can model either symmetric or asymmetric, unimodal or multimodal circular data, depending on the values of its four parameters. The probability density function (pdf) of GVM is in closed form and thus is convenient for inferences; see Yfantis and Borgman (1982) for details.

2 METHODS

2.1 Roles of some parameters in the BGVM model

The parameters κ and λ in a GVM (μ, ν, κ, λ) marginal control not only the concentration at θ = μ and θ = ν but also the graphic shape of the density. If κ = 0, the GVM is antipodally symmetric and has two modes, depending on λ, at θ = ν and θ = ν ± π. If λ = 0, the GVM reduces to the von Mises distribution, which is symmetric and unimodal, with mean direction μ and concentration κ; the larger κ is the more concentrated when the distribution is at μ. If μ12 = 0 , the BGVM is a unimodal distribution, and as κ12 increases the association between Θ1 and Θ2 increases, which indicates that the association between the given pair of circular genomes increases. From the copula representation in Section 2 of Shieh et al. (2006), we have that Φ1 = 2π F1(Θ1) given θ2 is VM (μ12 + 2πF2 (θ2), κ12). When μ12 = 0, Φ1 centers on 2πF2(θ2), and the dependence of Θ1 on Θ2 is controlled by the magnitude of κ12.

A BGVM generator written in R is available at http//:www.stat.sinica.edu.tw/∼gshieh/bgvm.htm.

2.2 Estimation and testing hypothesis under a BGVM distribution

2.2.1 MLEs of the parameters

Assuming that shared orthologs between a pair of circular genomes follow a BGVM distribution, given their converted angles we can immediately obtain the fitted BGVM distribution by applying the MLE algorithm in MLE_LR-test.R of the Supplementary Material. The MLE algorithm was modified from the Newton–Raphson method (Tanner, 1996), to prevent the estimates for the model in Equation (2) being trapped in local maxima, which was caused by the sinusoidal functions in the joint density. Next, we derive the limiting distribution of MLEs for the parameters in BGVM. The likelihood ratio test for independence of the organization between genomes is addressed at the end of this section.

To see how the MLE algorithm performs, we show its estimation results using data generated from BGVM with the parameters (μ1, ν1, κ1, λ1, μ2,  ,

,  and the sample size 100. We first estimated parameters of the marginals and obtained

and the sample size 100. We first estimated parameters of the marginals and obtained  and

and  . Next, we used these estimates as initial values and applied the MLE algorithm to estimate parameters of the joint density. The estimates obtained are

. Next, we used these estimates as initial values and applied the MLE algorithm to estimate parameters of the joint density. The estimates obtained are  ,

,  = (1.33, 1.65, 0.92, 0.95, 1.62, 1.55, 1.02, 0.90, 0.92, 2.32), which are quite close to the true values.

= (1.33, 1.65, 0.92, 0.95, 1.62, 1.55, 1.02, 0.90, 0.92, 2.32), which are quite close to the true values.

When the vector of parameters η belongs to the interior of the parameter set, the regularity conditions (see Section 3 of Shieh et al., 2006 for details) hold, and the consistency of the MLEs follows, which implies that the vector of MLEs multiplied by  converges to their true parameters. Asymptotic multivariate normality of the MLEs then follows from Lemma 1 and Theorem 2 of Self and Liang (1987), which indicates that this centered vector converges to a multivariate normal distribution as stated below.

converges to their true parameters. Asymptotic multivariate normality of the MLEs then follows from Lemma 1 and Theorem 2 of Self and Liang (1987), which indicates that this centered vector converges to a multivariate normal distribution as stated below.

Theorem 1.

has multivariate normal limiting distribution, and

has multivariate normal limiting distribution, and

Remark

If some of the parameters are known, then asymptotic normality holds for the reduced set with the corresponding entries in the information matrix.

has limiting distribution Z1I[Z1 > 0 ] , where Z1 has a normal distribution with variance determined from I−1. The cases where κ1 = 0, λ1 = 0, κ2 = 0 and/or λ2 = 0 are treated similarly.

has limiting distribution Z1I[Z1 > 0 ] , where Z1 has a normal distribution with variance determined from I−1. The cases where κ1 = 0, λ1 = 0, κ2 = 0 and/or λ2 = 0 are treated similarly.2.2.2 Testing for independence of the organization between circular genomes

There are really two cases, and the second case is the most complicated.

, Iij's are the (i, j) entries of the information matrix I(η) and c2 = c3 = 1/4 − c1. Furthermore,

, Iij's are the (i, j) entries of the information matrix I(η) and c2 = c3 = 1/4 − c1. Furthermore,

Codes in R to obtain MLEs and the LR test are available at http://www.stat.sinica.edu.tw/∼gshieh/bgvm.htm.

2.3 A novel circular correlation measure rpg

2.3.1 A circular grade correlation measure rg

is the MLE of the F2 marginal distribution and

is the MLE of the F2 marginal distribution and  and

and  are MLEs for κ12 and μ12.

are MLEs for κ12 and μ12.2.3.2 The large sample (limiting) distribution of rg

For each pair of genomes, the number of shared orthologs can range from a few hundred to more than two thousand. With such large sample sizes, the limiting distribution of the circular grade correlation estimate rg in general follows a normal distribution. To provide confidence intervals for ρg to judge whether the similarity on distributions of shared orthologs of paired circular genomes is different from zero (independence) or not, we derive the limiting distribution of the centered rg.

and

and  are derived in Appendix2.pdf of the Supplementary Material, which provides a proof for the convergence of the centered rg to a normal distribution.

are derived in Appendix2.pdf of the Supplementary Material, which provides a proof for the convergence of the centered rg to a normal distribution.The 1 − α confidence interval of ρg(θ1, θ2) is [rg − Zα/2D, rg + Zα/2D], where 0 < α < 1 and Zα/2 is the critical value of the standard normal distribution N(0, 1) at the level of α/2.

2.3.3 A visualization tool: rose diagrams

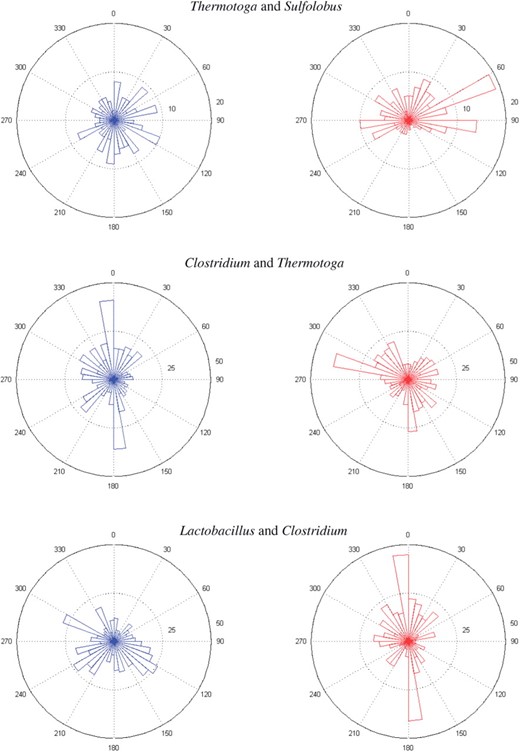

To visually depict association between paired circular genomes, we applied rose diagrams (a kind of angular histogram; Fisher, 1993) to each pair of shared orthologs. The radius of each sector with a binwidth of 10○ or other angles is proportional to the relative frequency of shared orthologs, whose corresponding angles belong to the sector, e.g. 60○ ∼ 70○ of the rose diagram of Sulfolobus in Figure 1, where the inner dotted (outer) circle denotes the frequency being 10 (20). In general, a small binwidth results in a bumpier rose diagram than that of a large one.

The rose diagrams of shared orthologs, identified by protein sequence similarity 0.7, of three pairs of prokaryotic genomes.

3 RESULTS

In this section, we apply the proposed procedures to shared orthologs between paired prokaryotic genomes to measure similarity of their genome organization. However, we note that our procedures can be applied to many features of genomic organization, e.g. shared TFBSs, shared repeated elements (Benson and Waterman, 1994) and shared non-coding genes (e.g. rRNA and small RNA), by inputting their corresponding angles instead of those of shared orthologs to our algorithm. For instance, both Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis have more verified TFBSs than other bacteria, and we can analyze their shared TFBSs using procedures developed here.

3.1 Data preprocessing

To let the shared orthologs between paired circular genomes reflect their similarity, we filtered out predicted horizontal transferred genes. The filtering was performed using data from the Horizontal Gene Transfer Database (Garcia-Vallve et al., 2003), which were accessed at http://genomes.urv.es/HGT-DB/. After the filtering, only species-specific genes were left in each circular genome, and we mapped their physical positions into angles ranged in [0, 2π). As an ortholog in each circular genome has a clustered orthologous group (COG) ID (Tatusov et al., 1997), the genes having the same COG ID in any paired circular genomes were identified as orthologs.

Paralogous genes (abbreviated as paralogs) are genes related by duplication within a genome. Due to gene duplication, there may be orthologous sets of paralogs within one genome, and several paralogs may share the same COG ID. That is, there are one-to-many, many-to-one and many-to-many corresponding shared orthologs besides the one-to-one corresponding ones. Using the following minimum angle distance, we can identify one-to-one shared orthologs. Let D(A, B) denote the distance between orthologs A and B, and D(A, B) = min{|angle of A − angle of B|, 2π − |angle of A − angle of B|}. For an orthologous set (multiple paralogs with the same COG ID), we use the shortest distance ortholog pairs (A, B), where Dmin(A, B) = mini,jD(Ai, Bj) and 1 ≤ i ≤ m, 1 ≤ j ≤ n, provided that m and n are orthologs in genomes A and B corresponding to one COG ID.

Let θij and θkj for 1 ≤ j ≤ n, denote the corresponding angle of the first base of the shared ortholog j in genomes i and k, which were used for statistical inferences. Note that within any given pair of genomes, the locations of distinct ortholog pairs are assumed to be independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) samples. Because marginals of shared ortholog genomes were often found to be asymmetric and bimodal, we fitted a BGVM model to each pair of shared orthologs for the prokaryotic genomes studied.

In the following, we apply the proposed BGVM procedures and rose diagrams to two sets of prokaryotic genomes, consisting of eight pairs of prokaryotic genomes separated from domain down to species, and 13 mycoplasma bacteria which are mammalian pathogens belonging to the same genus.

3.2 Application 1: eight pairs of prokaryotic genomes separated from domain to genus

In this application, we compare the structure organizations for each of the following pairs of bacterial genomes, which are (Thermotoga, Sulfolobus), (Clostridium, Thermotoga), (Lactobacillus, Clostridium), (Staphylococcus, Lactobacillus), (Oceanobacillus, Staphylococcus), (Bacillus, Oceanobacillus), (Bacillus anthracis, Bacillus subtitlis) and (Bacillus anthracis Ames, Bacillus anthracis Sterne). These pairs of genomes belong to different domains, the same domain, phylum class, order, family, genus and the same species, respectively. Among them, we first tested whether the genome structures of each pair are independent or not. After using the threshold of 0.7 for protein similarity to identify shared orthologs between each pair of genomes, we plotted their rose diagrams, which showed that several of the marginals are bimodal. Due to a space limit, only the rose diagrams (using a binwidth of 10○) of the first three pairs are presented in Figure 1; see Supplementary Figure S1 in Application1.pdf for all rose diagrams. Some marginal distributions of these pairs of bacterial genomes were asymmetric, based on the result of the test for symmetry in Pewsey (2002). For instance, some marginals of (Thermotoga, Sulfolobus), (Clostridium, Thermotoga) and (Lactobacillus, Clostridium) are asymmetric at the 95% significance level; see Table 1 for details.

| Bacteria name . | T n . | 97.5% critical value . | Symmetric . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermotoga | 0.66 | 1.96 | Yes |

| Sulfolobus | 5.23 | 1.96 | No |

| Clostridium | 5.75 | 1.96 | No |

| Thermotoga | 0.63 | 1.96 | Yes |

| Lactobacillus | |−0.93| | 1.96 | Yes |

| Clostridium | 2.96 | 1.96 | No |

| Bacteria name . | T n . | 97.5% critical value . | Symmetric . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermotoga | 0.66 | 1.96 | Yes |

| Sulfolobus | 5.23 | 1.96 | No |

| Clostridium | 5.75 | 1.96 | No |

| Thermotoga | 0.63 | 1.96 | Yes |

| Lactobacillus | |−0.93| | 1.96 | Yes |

| Clostridium | 2.96 | 1.96 | No |

| Bacteria name . | T n . | 97.5% critical value . | Symmetric . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermotoga | 0.66 | 1.96 | Yes |

| Sulfolobus | 5.23 | 1.96 | No |

| Clostridium | 5.75 | 1.96 | No |

| Thermotoga | 0.63 | 1.96 | Yes |

| Lactobacillus | |−0.93| | 1.96 | Yes |

| Clostridium | 2.96 | 1.96 | No |

| Bacteria name . | T n . | 97.5% critical value . | Symmetric . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermotoga | 0.66 | 1.96 | Yes |

| Sulfolobus | 5.23 | 1.96 | No |

| Clostridium | 5.75 | 1.96 | No |

| Thermotoga | 0.63 | 1.96 | Yes |

| Lactobacillus | |−0.93| | 1.96 | Yes |

| Clostridium | 2.96 | 1.96 | No |

For asymmetric and bimodal marginals of shared orthologs, it was reasonable to fit GVM distributions. Goodness-of-fit was checked by QQ-plots, similar to those in Shieh et al. (2006), which indicated that the fits were adequate for the marginals. For the fitted GVMs and QQ-plots, please see the file at http://www.stat.sinica.edu.tw/∼gshieh/bgvm.htm. The asymmetry and bimodality of the marginals suggested fitting a BGVM to shared orthologs for each pair of prokaryotic genomes. The MLE estimates of parameters in BGVM of (Thermotoga, Sulfolobus), (Clostridium, Thermotoga) and (Lactobacillus, Clostridium) are given in Table 2.

The shared orthologs of three pairs of circular genomes, identified by protein sequence similarity 0.7, fitted by BGVM models

| Genome (i, j) . |  .

. |  .

. |  .

. |  .

. |  .

. |  .

. |  .

. |  .

. |  .

. |  .

. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (6, 7) | 0.32 | 0.27 | 3.14 | 1.79 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 5.78 | 3.05 | 0.68 | 0.62 |

| (7, 8) | 0.28 | 0.40 | 5.39 | 3.13 | 0.13 | 0.31 | 4.87 | 2.25 | 0.28 | 6.21 |

| (8, 9) | 0.20 | 0.11 | 2.19 | 0.30 | 0.58 | 0.61 | 0.24 | 1.33 | 0.18 | 5.49 |

| Genome (i, j) . |  .

. |  .

. |  .

. |  .

. |  .

. |  .

. |  .

. |  .

. |  .

. |  .

. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (6, 7) | 0.32 | 0.27 | 3.14 | 1.79 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 5.78 | 3.05 | 0.68 | 0.62 |

| (7, 8) | 0.28 | 0.40 | 5.39 | 3.13 | 0.13 | 0.31 | 4.87 | 2.25 | 0.28 | 6.21 |

| (8, 9) | 0.20 | 0.11 | 2.19 | 0.30 | 0.58 | 0.61 | 0.24 | 1.33 | 0.18 | 5.49 |

Due to space limit, we use genome numbers 1–9 to represent the following nine prokaryotic genomes, respectively: Bacillus anthracis Ames, Bacillus anthracis Sterne, Bacillus subtilis, Oceanobacillus, Staphylococcus, Lactobacillus, Clostridium, Thermotoga and Sulfolobus.

The shared orthologs of three pairs of circular genomes, identified by protein sequence similarity 0.7, fitted by BGVM models

| Genome (i, j) . |  .

. |  .

. |  .

. |  .

. |  .

. |  .

. |  .

. |  .

. |  .

. |  .

. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (6, 7) | 0.32 | 0.27 | 3.14 | 1.79 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 5.78 | 3.05 | 0.68 | 0.62 |

| (7, 8) | 0.28 | 0.40 | 5.39 | 3.13 | 0.13 | 0.31 | 4.87 | 2.25 | 0.28 | 6.21 |

| (8, 9) | 0.20 | 0.11 | 2.19 | 0.30 | 0.58 | 0.61 | 0.24 | 1.33 | 0.18 | 5.49 |

| Genome (i, j) . |  .

. |  .

. |  .

. |  .

. |  .

. |  .

. |  .

. |  .

. |  .

. |  .

. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (6, 7) | 0.32 | 0.27 | 3.14 | 1.79 | 0.31 | 0.49 | 5.78 | 3.05 | 0.68 | 0.62 |

| (7, 8) | 0.28 | 0.40 | 5.39 | 3.13 | 0.13 | 0.31 | 4.87 | 2.25 | 0.28 | 6.21 |

| (8, 9) | 0.20 | 0.11 | 2.19 | 0.30 | 0.58 | 0.61 | 0.24 | 1.33 | 0.18 | 5.49 |

Due to space limit, we use genome numbers 1–9 to represent the following nine prokaryotic genomes, respectively: Bacillus anthracis Ames, Bacillus anthracis Sterne, Bacillus subtilis, Oceanobacillus, Staphylococcus, Lactobacillus, Clostridium, Thermotoga and Sulfolobus.

Employing the LR-test based on the distributions of shared orthologs, we test whether genome organization of each pair of these prokaryotes are independent. (Not) rejecting this hypothesis indicates that their genome organizations are (not) correlated. For each pair of prokaryotic genomes, a LR-test of shared orthologs was computed, and the result showed that except (Thermotoga, Sulfolobus), the hypothesis was rejected for the other seven pairs at a 95% level using Case 2; see Application1.pdf of the Supplementary Material for details. This result indicates that for these seven pairs, their genome organizations are correlated based on the similarity of the distributions of their shared orthologs. This association can also be seen easily from their rose diagrams, in particular those of Bacillus anthracis Ames and Bacillus anthracis Sterne.

Next, we estimated the association of genome organizations of each of the eight pairs of prokaryotes. Note that the origins of most prokaryotic genomes are unknown (and having no rules to predict) or predicted, which demonstrates the importance of rpg's being invariant to the origins of both circular genomes. The values of rp, rg and rpg of these pairs (in Table 3) are incidentally consistent with their phylogeny relationships. The rose diagrams show that the genome structures of Bacillus anthracis Ames and Bacillus anthracis Sterne are almost identical, while those of Thermotoga and Sulfolobus are not at all alike.

The values of correlation measures rg, rp, rpg of nine prokaryotic genomes based on similarity of the distribution of shared orthologs

| (Genome i, Genome j) . | r g . | r p . | r pg . |

|---|---|---|---|

| ( 1, 2 ) | 0.84 | 0.49 | 0.67 |

| ( 2, 3 ) | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.44 |

| ( 3, 4 ) | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.47 |

| ( 4, 5 ) | 0.36 | 0.50 | 0.43 |

| ( 5, 6 ) | 0.24 | 0.51 | 0.38 |

| ( 6, 7 ) | 0.20 | 0.34 | 0.27 |

| ( 7, 8 ) | 0.08 | 0.30 | 0.19 |

| ( 8, 9 ) | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.08 |

| (Genome i, Genome j) . | r g . | r p . | r pg . |

|---|---|---|---|

| ( 1, 2 ) | 0.84 | 0.49 | 0.67 |

| ( 2, 3 ) | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.44 |

| ( 3, 4 ) | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.47 |

| ( 4, 5 ) | 0.36 | 0.50 | 0.43 |

| ( 5, 6 ) | 0.24 | 0.51 | 0.38 |

| ( 6, 7 ) | 0.20 | 0.34 | 0.27 |

| ( 7, 8 ) | 0.08 | 0.30 | 0.19 |

| ( 8, 9 ) | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.08 |

The values of correlation measures rg, rp, rpg of nine prokaryotic genomes based on similarity of the distribution of shared orthologs

| (Genome i, Genome j) . | r g . | r p . | r pg . |

|---|---|---|---|

| ( 1, 2 ) | 0.84 | 0.49 | 0.67 |

| ( 2, 3 ) | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.44 |

| ( 3, 4 ) | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.47 |

| ( 4, 5 ) | 0.36 | 0.50 | 0.43 |

| ( 5, 6 ) | 0.24 | 0.51 | 0.38 |

| ( 6, 7 ) | 0.20 | 0.34 | 0.27 |

| ( 7, 8 ) | 0.08 | 0.30 | 0.19 |

| ( 8, 9 ) | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.08 |

| (Genome i, Genome j) . | r g . | r p . | r pg . |

|---|---|---|---|

| ( 1, 2 ) | 0.84 | 0.49 | 0.67 |

| ( 2, 3 ) | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.44 |

| ( 3, 4 ) | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.47 |

| ( 4, 5 ) | 0.36 | 0.50 | 0.43 |

| ( 5, 6 ) | 0.24 | 0.51 | 0.38 |

| ( 6, 7 ) | 0.20 | 0.34 | 0.27 |

| ( 7, 8 ) | 0.08 | 0.30 | 0.19 |

| ( 8, 9 ) | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.08 |

3.3 Application 2: 13 mycoplasma bacteria

Above we showed that the BGVM distribution and its inference procedures can be applied to distinguish genome organization of eight pairs of bacteria in Application 1, in which genomes of six pairs were relatively distant (from different genus or beyond). Here, we apply the proposed procedures to a set of 13 mycoplasma bacteria, which are relatively close in phylogeny, to see if rpg can distinguish their genome organization. These bacteria are mammalian pathogens with small genomes, which belong to the same genus. Specifically, their phylogeny tree based on 16S ribosomal sequence, constructed by the software MEGA4, is in Application2.pdf of the Supplementary Material. Among these bacterial genomes, three origins are unknown and nine are predicted, which demonstrates the need of a correlation measure invariant to the origin of a circular genome such as rpg.

The pairwise rose diagrams (with a binwidth of 10○) of these 13 bacterial genomes showed that several of the marginals were bimodal and asymmetric; see http://www.stat.sinica.edu.tw/∼gshieh/bgvm.htm for details. Hence, we fitted a BGVM distribution to the shared orthologs for each pair of bacterial genomes. Next, the correlation measure rpg was applied to these genomes to result in the values in Table 4.

The values of correlation measure rpg between 13 mycoplasma bacteria based on similarity of the distribution of shared orthologs

| . | r pg . | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . | 8 . | 9 . | 10 . | 11 . | 12 . | 13 . |

| 1 | – | 0.28 | 0.25 | 0.77 | 0.25 | 0.28 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.39 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.28 |

| 2 | – | – | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.30 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.35 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.25 |

| 3 | – | – | – | 0.19 | 0.33 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.30 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.24 |

| 4 | – | – | – | – | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.27 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.27 |

| 5 | – | – | – | – | – | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.29 | 0.17 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.21 |

| 6 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.26 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.18 |

| 7 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.71 | 0.27 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.20 |

| 8 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.27 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| 9 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.18 |

| 10 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.25 |

| 11 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.60 | 0.24 |

| 12 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.22 |

| 13 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| . | r pg . | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . | 8 . | 9 . | 10 . | 11 . | 12 . | 13 . |

| 1 | – | 0.28 | 0.25 | 0.77 | 0.25 | 0.28 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.39 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.28 |

| 2 | – | – | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.30 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.35 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.25 |

| 3 | – | – | – | 0.19 | 0.33 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.30 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.24 |

| 4 | – | – | – | – | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.27 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.27 |

| 5 | – | – | – | – | – | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.29 | 0.17 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.21 |

| 6 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.26 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.18 |

| 7 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.71 | 0.27 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.20 |

| 8 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.27 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| 9 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.18 |

| 10 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.25 |

| 11 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.60 | 0.24 |

| 12 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.22 |

| 13 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

Due to space limit, we use genome numbers 1–13 to represent the following 13 bacterial genomes, respectively: M. genitalium G37, M. mobile 163K, M.synoviae 53, M.pneumoniae M129, M.agalactiae PG2, M.hyopneumoniae 232, M.hyopneumoniae J, M.hyopneumoniae 7448, M.pulmonis UAB CTIP, M.gallisepticum R, M.capricolum subsp. capricolum ATCC 27343, M.mycoides subsp. mycoides SC str. PG1, and M.penetrans HF-2. Further, No. denotes genome numbers.

The values of correlation measure rpg between 13 mycoplasma bacteria based on similarity of the distribution of shared orthologs

| . | r pg . | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . | 8 . | 9 . | 10 . | 11 . | 12 . | 13 . |

| 1 | – | 0.28 | 0.25 | 0.77 | 0.25 | 0.28 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.39 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.28 |

| 2 | – | – | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.30 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.35 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.25 |

| 3 | – | – | – | 0.19 | 0.33 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.30 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.24 |

| 4 | – | – | – | – | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.27 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.27 |

| 5 | – | – | – | – | – | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.29 | 0.17 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.21 |

| 6 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.26 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.18 |

| 7 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.71 | 0.27 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.20 |

| 8 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.27 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| 9 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.18 |

| 10 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.25 |

| 11 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.60 | 0.24 |

| 12 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.22 |

| 13 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| . | r pg . | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . | 8 . | 9 . | 10 . | 11 . | 12 . | 13 . |

| 1 | – | 0.28 | 0.25 | 0.77 | 0.25 | 0.28 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.39 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.28 |

| 2 | – | – | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.30 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.35 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.25 |

| 3 | – | – | – | 0.19 | 0.33 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.30 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.24 |

| 4 | – | – | – | – | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.27 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.27 |

| 5 | – | – | – | – | – | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.29 | 0.17 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.21 |

| 6 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.26 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.18 |

| 7 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.71 | 0.27 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.20 |

| 8 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.27 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| 9 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.18 |

| 10 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.25 |

| 11 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.60 | 0.24 |

| 12 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.22 |

| 13 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

Due to space limit, we use genome numbers 1–13 to represent the following 13 bacterial genomes, respectively: M. genitalium G37, M. mobile 163K, M.synoviae 53, M.pneumoniae M129, M.agalactiae PG2, M.hyopneumoniae 232, M.hyopneumoniae J, M.hyopneumoniae 7448, M.pulmonis UAB CTIP, M.gallisepticum R, M.capricolum subsp. capricolum ATCC 27343, M.mycoides subsp. mycoides SC str. PG1, and M.penetrans HF-2. Further, No. denotes genome numbers.

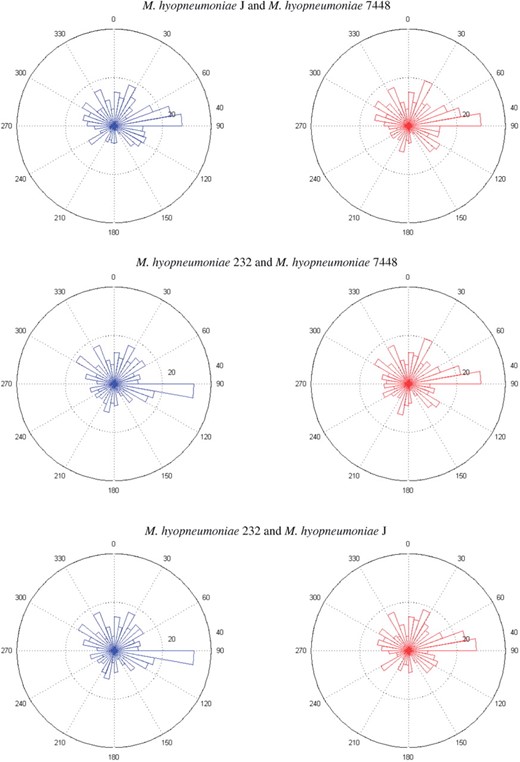

Interestingly, these associations are consistent with those measured based on similarity of their 16S rRNAs. Among these 13 bacterial genomes, the top few correlated pairs in terms of rpg are (M.genitalium G37, M.pneumoniae M129), (M.hyopneumoniae J, M.hyopneumoniae 7448), (M.hyopneumoniae 232, M.hyopneumoniae 7448) and (M.hyopneumoniae 232, M.hyopneumoniae J), whose values are equal to 0.77, 0.71, 0.69 and 0.67, respectively. The latter three pairs are hyopneumoniae, which cause chronic disease in pigs and attach to the same organ (lung cilia). From the rose diagrams of these hyopneumoniae in Figure 2, we can see that their genome structures are quite similar in terms of shared orthologs. The most favored regions of their shared orthologs are 80○ − 90○, (20○ − 30○ and 330○ − 340○) and (20○ − 30○ and 330○ − 340○), respectively, in which 23, (16 and 17) and (14 and 16) genes are in common, respectively. Among these genes, the largest common functional group is translation, and their gene orders are also conserved. For details, please see Supplementary Tables S1 and S2 in Application2.pdf. In particular, the rose diagrams of (M.hyopneumoniae J, M.hyopneumoniae 7448) clearly depict their similarity in genome organization, and the most and least favored regions of shared orthologs are 80○ − 90○ and 150○ − 160○, respectively. The genes located in the most favored region, encode ribosomal subunit proteins 30S and 50S, which are essential genes and are known to cluster together to form an operon structure in many bacterial genomes (Bratlie et al., 2010).

The rose diagrams of shared orthologs, identified via protein sequence similarity 0.7, of three pairs of hyopneumoniae bacteria.

Moreover, the aforementioned relationships depicted by rose diagrams are consistent with those of the other analysis on genome organization (Application2.pdf of the Supplementary Material). Thus, our procedures may provide useful information on comparing the organization of circular genomes and genome construction in synthetic biology.

4 DISCUSSION

The proposed BGVM distribution, with flexible and closed-formed marginal distributions, was shown to model paired angular data well, in which each marginal of the pair can be asymmetric or/and multimodal, e.g. shared orthologs between paired bacterial genomes. Statistical inferences employing the MLEs for parameters of the BGVM distribution and the LR-test for independence of the organization between circular genomes are established. A novel circular correlation measure (rpg), invariant to the choices of origins of circular genomes which are mainly unknown or predicted, was derived and a visualization tool provided. We applied these procedures to two sets of prokaryotic genomes, consisting a set of relatively distant prokaryotes and a set of closely related bacteria. The novel correlation measure rpg was shown to summarize associations between prokaryotic genomes well. While the rose diagrams further depict their associations via distributions of the shared orthologs. Our results are consistent with those of other analysis. Thus, the BGVM procedures may provide useful information on the organization of circular genomes.

We note that the BGVM procedures can be applied to identify shared TFBSs, shared coding or non-coding genes and shared repeated elements between circular genomes. Thus, they may be applied to identifying conserved chromosome backbones, detecting conserved gene clusters such as operons, among others, which can be used for genome construction in synthetic biology.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are indebted to Jia-Hong Wu and Su-Wei Hsu for computational assistance; Shih-Chung Chuang for statistical assistance. We thank Chuang-Hsiung Chang for discussions, and the AE and two reviewers for constructive comments that improved this article.

Funding: Shurong Zheng was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from Academia Sinica thematic grant (23-33); the research was supported in part by National Science Council, Republic of China (96-2118-M-001-010-MY2) and National Research Program-Genome Medicine grant (NSC99-3112-B-001-015) for G.S.S.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

Author notes

† Present address: Shurong Zheng, KLAS and Mathematics and Statistics, Northeast Normal University, Changchun 130024, China.

Associate Editor: Alfonso Valencia