-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Natalia Vidal-Laureano, Carlos T Huerta, Eduardo A Perez, Steven Alexander Earle, Augmented Safety Profile of Ultrasound-Guided Gluteal Fat Transfer: Retrospective Study With 1815 Patients, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 44, Issue 4, April 2024, Pages NP263–NP270, https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjad377

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Gluteal augmentation with autologous fat transfer is one of the fastest growing aesthetic surgical procedures worldwide over the past decade. However, this procedure can be associated with high mortality from fatal pulmonary fat embolism events caused by intramuscular injection of fat. Ultrasound-guided fat grafting allows visualization of the transfer in the subcutaneous space, avoiding intramuscular injection.

The aim of this study was to assess the safety and efficacy of gluteal fat grafting performed with ultrasound-guided cannulation.

A retrospective chart review of all patients undergoing ultrasound-guided gluteal fat grafting at the authors’ center between 2019 and 2022 was performed. All cases were performed by board-certified and board-eligible plastic surgeons under general anesthesia in ASA Class I or II patients. Fat was only transferred to the subcutaneous plane when over the gluteal muscle. Patients underwent postoperative follow-up from a minimum of 3 months up to 2 years. Results were analyzed with standard statistical tests.

The study encompassed 1815 female patients with a median age of 34 years. Controlled medical comorbidities were present in 14%, with the most frequent being hypothyroidism (0.7%), polycystic ovarian syndrome (0.7%), anxiety (0.6%), and asthma (0.6%). Postoperative complications occurred in 4% of the total cohort, with the most common being seroma (1.2%), local skin ischemia (1.2%), and surgical site infection (0.8%). There were no macroscopic fat emboli complications or mortalities.

These data suggest that direct visualization of anatomic plane injection through ultrasound guidance is associated with a low rate of complications. Ultrasound guidance is an efficacious adjunct to gluteal fat grafting and is associated with an improved safety profile that should be considered by every surgeon performing this procedure.

Gluteal contouring and augmentation with fat grafting is not a new procedure, having now been performed for over 4 decades,1 but has become very popular in the last decade. It is one of the fastest-growing procedures worldwide as documented by the International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery 2021, with a 34.1% growth between 2020 and 2021.2 A similar increase was found by The Aesthetic Society, which reported a 37% increase in buttock augmentations (fat grafting and implants) from 2020 to 2021.3 But with the increase in popularity, we have unfortunately also seen an increase in catastrophic complications. Mortalities from gluteal fat grafting were first reported in 2015 from Mexico and Colombia, with 22 deaths in the previous 10 and 15 years, respectively.4 These cases were reviewed, and it was found that all showed evidence of intramuscular fat being present. Consequently, it was recommended to avoid injection into the deep gluteal muscle.

The popularity of the procedure continued to grow and with it the number of fatal cases, leading to a survey by the Aesthetic Surgery Education and Research Foundation sent to all active members of the American Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery and the International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery in 2017 to document the incidence of fatal and nonfatal pulmonary fat embolism and mortality rate. The survey found an annual mortality rate of 1:3448.5

During this same year, 2017, South Florida saw the highest number of Brazilian butt lift deaths, 5, in the United States up to that date.6 This contributed to the creation of an international intersociety work group called the Gluteal Fat Grafting Task Force, led by Dr Peter Rubin, MD. The goal was “to create an appropriate anatomic model to study the pathophysiology behind these deaths, identify contributing anatomic factors and determine safer fat graft injection techniques.”7 After performing cadaver studies a consensus was reached, and in 2018 the Task Force made the following recommendations: fat graft should be injected in the subcutaneous space; intergluteal access is preferable to avoid deep angulation; instruments should offer control of the cannula and therefore a rigid cannula should be used to avoid inadvertent bending and Luer connections should be avoided as well; and injection should only be done while the cannula is in motion.7

As a response to the increased mortality rates of this procedure, especially in South Florida, the Florida Board of Medicine conducted a special meeting in 2019. The result was an emergent rule that prohibited injection of fat deep to the superficial gluteal fascia, intramuscularly or submuscularly.8 Unfortunately, this did not slow down the alarming mortality rate we were experiencing in South Florida. In fact, the deadliest year on record for Brazilian butt lift mortality in South Florida was 2021, in which there were 6 fatalities.6

Traditionally, fat transfer is done blindly with the correct location being identified based solely on experience and feel. Ultrasound guidance allows the surgeon to be able to see the cannula in real time. It has been shown with ultrasound there are consistently 5 layers in the gluteal subcutaneous anatomy (skin, superficial fat, superficial fascia, deep fat, deep fascia), independent of age, sex, or BMI.9 Other techniques to avoid intramuscular fat injection, such as angle on injection, cannula thickness, access incision, among others,10-15 have been proposed to decrease this risk. But unfortunately, even after all these recommendations, and surgeons following them, we kept on seeing fat embolism cases.6 Therefore, tactile feedback alone is not enough to avoid intramuscular injection of fat in the gluteal region.16

The use of ultrasound to guide fat transfer has been described by Pazmiño.17,18 This method, which involves injecting the fat in a static manner using real-time ultrasound guidance, has been shown to yield safe results. Recently the Florida Department of Health instituted a law mandating all surgeons to use ultrasound imaging when performing fat transfer.19 This has been supported by the American Society of Plastic Surgeons and The Aesthetic Society. In our busy center, ultrasound-guided gluteal fat transfer has been performed since 2019. The aim of the current study was to assess the safety and efficacy of gluteal fat grafting utilizing ultrasound-guided cannulation.

METHODS

A retrospective chart review of all patients undergoing ultrasound-guided gluteal fat grafting at our center between September 2019 and September 2022 was performed. No cases of liposuction and fat transfer to buttocks performed during this period were excluded from the data analysis. IRB approval was not obtained as this study qualified for exemption. Medical charts were accessed to obtain the information required, but patient identifiers were not linked to the research data set. Written consent was obtained, by which the patients agreed to the use and analysis of their data. Declaration of Helsinki guidelines were used to guide this study. All cases were performed by board-certified and board-eligible plastic surgeons (American Board of Plastic Surgery) under general anesthesia in American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) Class I or II patients. Fat was only transferred to the subcutaneous plane when over the gluteal muscle. Patients underwent postoperative follow-up from a minimum of 3 months up to 2 years.

We retrieved demographic and clinical data including age, gender, comorbidities, BMI, volume of tumescence fluid infiltrated, total lipoaspirate, volume of fat injected, and operative time. Complications, including seroma, local skin ischemia, surgical site infection, fat necrosis, dehydration, hematoma, and macroscopic fat embolism, were reviewed. In addition, any other complications seen were included in a separate column as “miscellaneous.” Results were analyzed with standard statistical tests.

Procedure

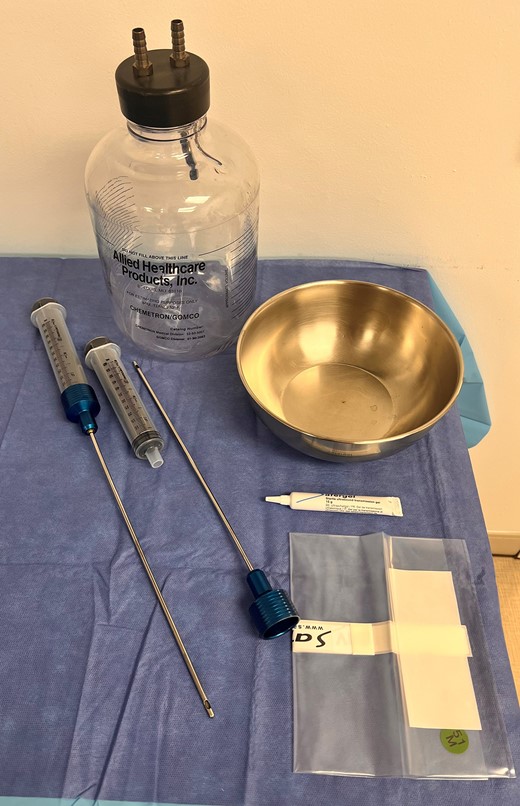

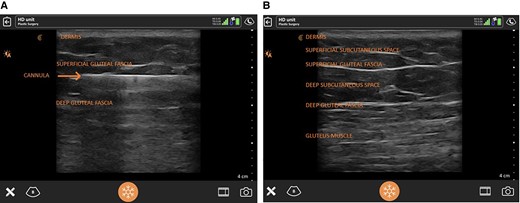

All patients were treated in our Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations–certified office-based surgery facility by board-certified and board-eligible plastic surgeons. All procedures were performed under general anesthesia. Procedure was started with the patient in the supine position. Liposuction to the anterior torso was performed first. A super-wet technique was used with tumescence fluid prepared with 2 mg of epinephrine in 1 liter of 0.9% normal saline. Power-assisted liposuction was performed with a 4-mm basket cannula. At completion of liposuction, a 10fr Jackson-Pratt drain was left in the lower abdomen and incisions were closed. The patient was then placed in a prone, flexed position. Liposuction to the posterior trunk was performed in a similar manner. Fat was prepared by the decantation method and transferred to 60-mL syringes for injection. Figure 1 shows the equipment used. Incisions for gluteal fat transfer were made in the midline intergluteal crease and bilateral inferior gluteal folds. A portable ultrasound (Clarius L15 HD3) was used in all patients to assess the gluteal layers in real time, as shown in Figure 2, and for the fat transfer portion over the gluteal muscle. A 5-mm blunt-tip, single-hole cannula was used for injection. Fat was injected in a retrograde manner or static in boluses using a 60-mL syringe while observing it with ultrasound (as shown in the Video, available online at www.aestheticsurgeryjournal.com). The final volume injected was determined by skin elasticity and final aesthetic shape. Patients were placed in a compression garment and discharged home. Follow-ups were done at 24 hours, 1 week, 6 weeks, 3 months, and 2 years.

Equipment used: 60-mL syringes with Toomey-type tip, blunt-tip 5-mm single-hole infiltrating cannulas, sterile bowl for fat placement, 2800-mL glass collection bottle, and sterile bag and gel for ultrasound.

Ultrasound view of gluteal anatomy with layers labeled (dermis, superficial subcutaneous space, superficial gluteal fascia, deep subcutaneous space, deep gluteal fascia, and gluteal muscle) with (A) and without (B) the infiltrating cannula.

RESULTS

The study period covered 1815 female patients with a median age of 34 years (range, 18-58 years). Controlled medical comorbidities were present in 14%, with the most frequent being hypothyroidism (0.7%), polycystic ovarian syndrome (0.7%), anxiety (0.6%), and asthma (0.6%). BMI ranged from 22.2 to 34.6 kg/m2, with an average of 28.3 kg/m2. The mean total volume infiltrated was 4600 mL (range, 3500-5800 mL), and the mean total lipoaspirate volume was 4300 mL (range, 3100-4900 mL). The mean volume of fat transferred to the buttocks and hip region was 720 mL (range, 540-1200 mL), and the mean operative time it took surgeons to transfer the fat (injecting time) was 28 minutes (range, 20-39 minutes); this included the usage of ultrasound during the transfer which was not documented separately. Postoperative complications occurred in 4% of the total cohort, with the most common being seroma (1.2%), local skin ischemia (1.2%), and surgical site infection (0.8%; Table 1). There were no macroscopic fat emboli complications or mortalities.

Postoperative Complications Among Patients Undergoing Ultrasound-Guided Gluteal Fat Grafting Procedures From 2019 to 2022

| Characteristic . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Any complication | 72 (4) |

| Seroma | 21 (1.2) |

| Local skin ischemia | 22 (1.2) |

| Surgical site infection | 14 (0.8) |

| Fat necrosis | 6 (0.3) |

| Miscellaneousa | 6 (0.3) |

| Dehydration | 2 (0.1) |

| Hematoma | 2 (0.1) |

| Macroscopic fat embolism | 0 (0) |

| Mortality | 0 (0) |

| Characteristic . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Any complication | 72 (4) |

| Seroma | 21 (1.2) |

| Local skin ischemia | 22 (1.2) |

| Surgical site infection | 14 (0.8) |

| Fat necrosis | 6 (0.3) |

| Miscellaneousa | 6 (0.3) |

| Dehydration | 2 (0.1) |

| Hematoma | 2 (0.1) |

| Macroscopic fat embolism | 0 (0) |

| Mortality | 0 (0) |

aArrhythmia, thrombophlebitis, allergy to antibiotics.

Postoperative Complications Among Patients Undergoing Ultrasound-Guided Gluteal Fat Grafting Procedures From 2019 to 2022

| Characteristic . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Any complication | 72 (4) |

| Seroma | 21 (1.2) |

| Local skin ischemia | 22 (1.2) |

| Surgical site infection | 14 (0.8) |

| Fat necrosis | 6 (0.3) |

| Miscellaneousa | 6 (0.3) |

| Dehydration | 2 (0.1) |

| Hematoma | 2 (0.1) |

| Macroscopic fat embolism | 0 (0) |

| Mortality | 0 (0) |

| Characteristic . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Any complication | 72 (4) |

| Seroma | 21 (1.2) |

| Local skin ischemia | 22 (1.2) |

| Surgical site infection | 14 (0.8) |

| Fat necrosis | 6 (0.3) |

| Miscellaneousa | 6 (0.3) |

| Dehydration | 2 (0.1) |

| Hematoma | 2 (0.1) |

| Macroscopic fat embolism | 0 (0) |

| Mortality | 0 (0) |

aArrhythmia, thrombophlebitis, allergy to antibiotics.

DISCUSSION

Macroscopic fat embolism has been a catastrophic complication we started seeing as gluteal fat grafting became more popular. There were 25 fatal cases of macroscopic fat embolism in South Florida between January 2010 and April 2022,6 a rate that has triggered various legislative measures to regulate and make this procedure safer.19 A comprehensive review of these cases, the South Florida experience, and the pathophysiology of this complication has been recently published.6 The authors of this thorough review concluded that intramuscular fat injection was responsible for macroscopic fat embolism. Intramuscular injection was previously encouraged to promote a well-vascularized bed for the fat transferred, to ensure fat viability,20 and to increase the volume injected.21 Multiple studies have reported the dangers of this technique and the importance of performing only subcutaneous fat transfer.4-7,9-12,14,15,22-27 This has also been recommended by the last published “Practice Advisory on Gluteal Fat Grafting” in 2022.28 In the South Florida experience, in every case reviewed autopsy dissection revealed evidence of fat in the gluteal muscle.6 It is also important to mention that the extent of fat in this compartment did not correlate with inadvertent intramuscular fat injections. It is believed this was the result of intentional intramuscular fat grafting or the result of the surgeon not being aware of their cannula position at the time of injection.

Differentiating between macroscopic and microscopic fat embolism has been very important in understanding the pathophysiology of this condition. A thorough review of both pathological entities by Cardenas-Camarena et al revealed the importance of prevention and the dangers of muscular fat injection leading to fat embolism, cardiovascular collapse, and death.22 They also found that a complete cut or direct cannulation of the gluteal veins is not necessary for macroscopic fat embolism to occur due to the constant negative pressure that the gluteal venous system maintains. This makes it paramount to directly visualize the placement of fat in the subcutaneous space.

Fat grafting has long been performed “blind,” guided primarily by the surgeons’ tactile feel and anatomic knowledge. Experienced surgeons who have performed numerous fat grafting procedures vouch for experience as the most important component for knowledge of the cannula tip position and avoidance of intramuscular injection. Unfortunately, there are several cases of macroscopic fat embolism with experienced surgeons documenting only subcutaneous injection and with evidence of fat in the muscular plane after postmortem examination.6 This tells us that experience and anatomic knowledge are not enough to avoid this complication.

The use of ultrasound in plastic surgery has become more popular in the last few decades. Its benefits include the fact that it is noninvasive, poses no radiation risk, is painless, has a patient-friendly technique, and a short learning curve, making it more accessible and usable for practitioners.29 Interest in plastic surgeon–led ultrasound has diversified starting from microsurgery and lymphedema surgery to identify small vessels and avoid unnecessary donor sites, to breast procedures for identification of postoperative complications, such as hematoma and seromas, and even capsular contracture. The use of ultrasound to guide fat transfer was studied by D’Amico and co-workers in 15 patients, showing its efficacy and reliability.30 They mention as limitations the cost of ultrasound and the need for an assistant to hold the probe. In our practice, both surgeons use a surgeon-held technique (Video). With the nondominant hand, the probe is held, and the dominant hand is used for injecting. The probe may be put down for 2-hand proprioception when inserting the cannula, and then the probe is placed to confirm subcutaneous cannula placement before and during the injection.

The learning curve associated with ultrasound use is not steep. Proper knowledge of the anatomy of the gluteal region is most important. In our practice, the senior surgeon has been utilizing ultrasound for all his gluteal fat transfer procedures since 2019. The junior surgeon joined this practice after training in 2021 and was proctored by the senior surgeon for approximately 20 cases, after which, based on observation by the senior surgeon, he was deemed safe to proceed without supervision. In our experience, ultrasound is extremely useful for teaching the procedure and ensuring patient safety.

Regarding surgical time, it is a concern of most surgeons that the use of real-time ultrasound will increase their operative time. As mentioned before, the learning curve is not steep and even in the first few cases, operative time only increased by 10 to 15 minutes. As surgeons become more familiar with the device and identification of the cannula, the extra time may come down to approximately 5 minutes. Due to the retrospective nature of this study, there are no data on the amount of time it took the surgeons to use the ultrasound. What is documented in the charts is the time of fat transfer, which was an average of 28 minutes. The use of ultrasound is only necessary while injecting over the gluteal muscle.

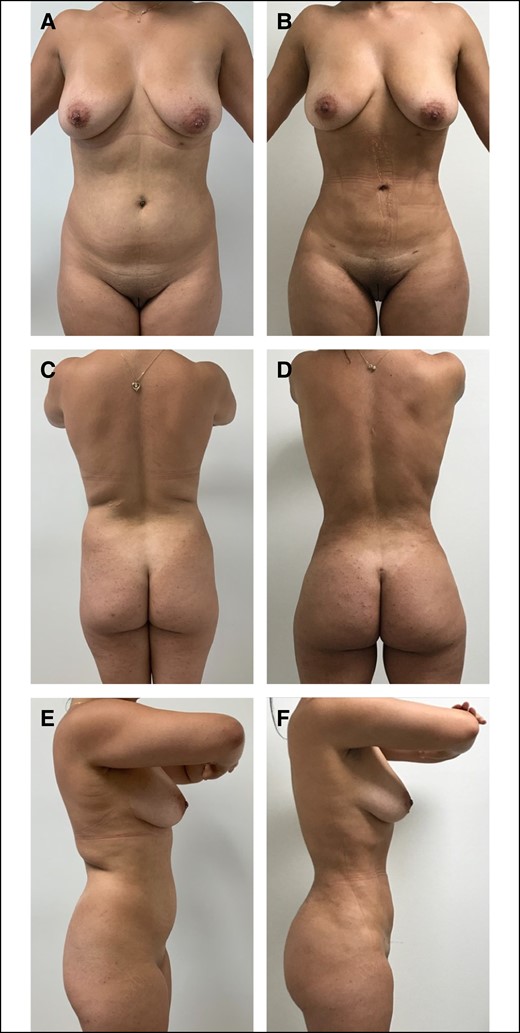

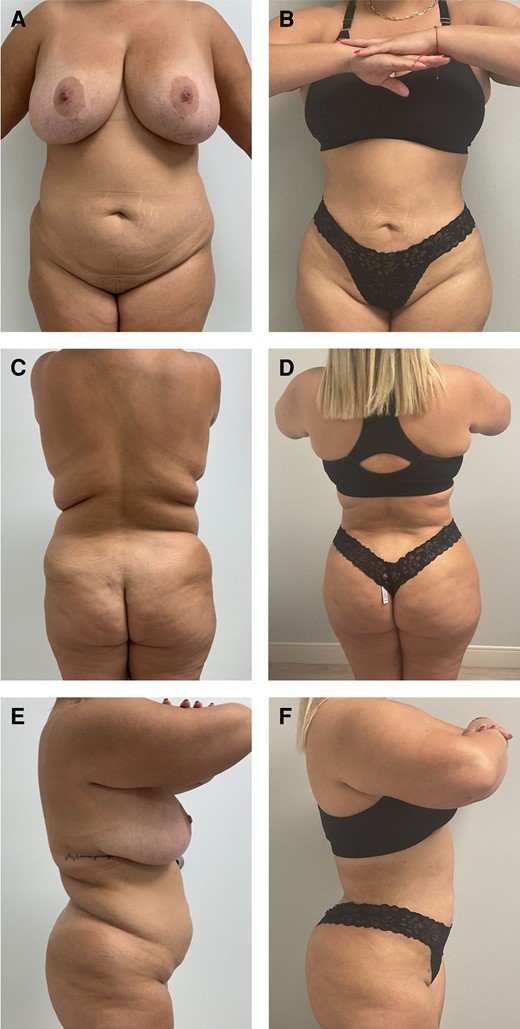

Another important aspect to discuss is the maintenance and even improvement of results. By using real-time ultrasound, not only can you ensure fat grafting only in the subcutaneous space, but you can selectively inject in the deep or the superficial subcutaneous spaces. The authors have observed differences in the projection and shape while injecting in the different planes (Figures 3-6). The deep subcutaneous space allows for more projection and volumetric expansion, while the superficial subcutaneous space allows for more subtle correction of flat areas and indentations. This experience is shared by Pazmiño and Del Vecchio et al, who recommend a mainly deep subcutaneous space injection to avoid “blow out fracture, skin changes and surface irregularities.”18 Fat viability in the subcutaneous space has been found to be comparable to that in the muscular plane.31

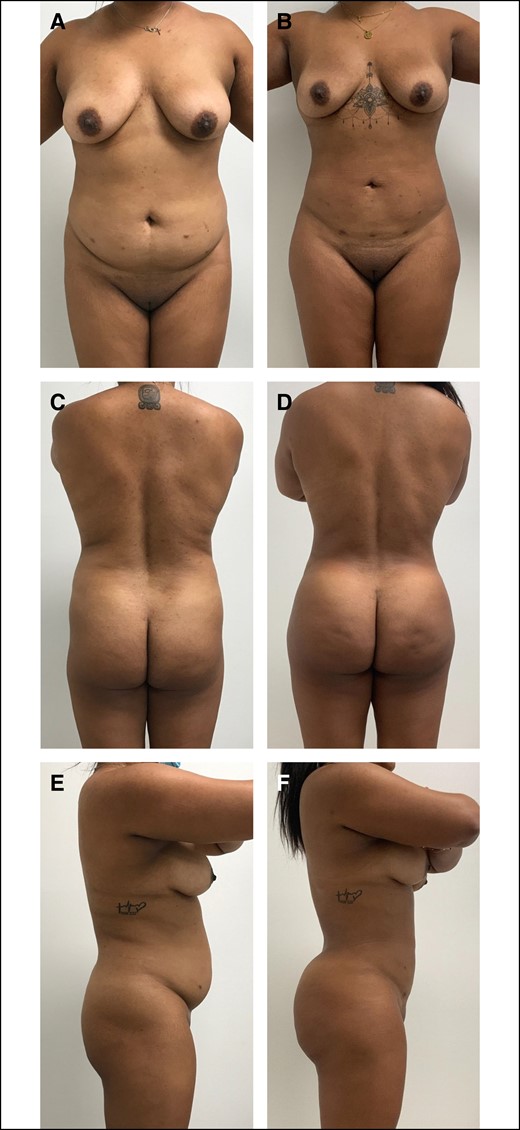

A 23-year-old female patient who is 6 months postoperative liposuction and ultrasound-guided fat transfer to buttocks and hips. She had a BMI of 26.1 kg/m2 and the total fat transferred was 720 mL. (A) Preoperative anterior view, (B) postoperative anterior view, (C) preoperative posterior view, (D) postoperative posterior view, (E) preoperative lateral view, and (F) postoperative lateral view.

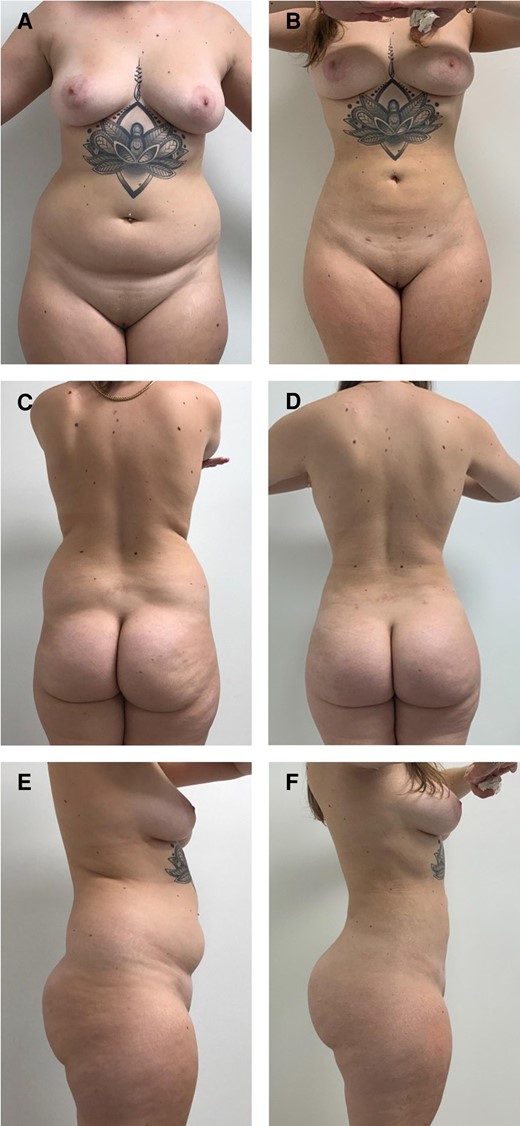

A 34-year-old female patient who is 2 years postoperative liposuction and ultrasound-guided fat transfer to buttocks and hips. She had a BMI of 29.5 kg/m2 and the total fat transferred was 780 mL. (A) Preoperative anterior view, (B) postoperative anterior view, (C) preoperative posterior view, (D) postoperative posterior view, (E) preoperative lateral view, and (F) postoperative lateral view).

A 33-year-old female patient who is 8 months postoperative liposuction and ultrasound-guided fat transfer to buttocks and hips. She had a BMI of 26.1 kg/m2 and the total fat transferred was 840 mL. (A) Preoperative anterior view, (B) postoperative anterior view, (C) preoperative posterior view, (D) postoperative posterior view, (E) preoperative lateral view, and (F) postoperative lateral view.

A 21-year-old female patient who is 6 months postoperative liposuction and ultrasound-guided fat transfer to buttocks and hips. She had a BMI of 27.4 kg/m2 and the total fat transferred was 900 mL. (A) Preoperative anterior view, (B) postoperative anterior view, (C) preoperative posterior view, (D) postoperative posterior view, (E) preoperative lateral view, and (F) postoperative lateral view.

Our findings show that ultrasound guidance of fat transfer to the gluteal region provides accurate visualization, avoiding inadvertent intramuscular injection and consequently minimizing the risk of macroscopic fat embolism. The limitations of this study are its retrospective nature, that only 2 surgeons participated in the study, and the lack of postoperative imaging to demonstrate the lack of intramuscular fat.

CONCLUSIONS

Ultrasound allows for direct visualization of the cannula in real time to ensure fat is placed in the safe subcutaneous plane, thereby minimizing the risk of fat embolism. The ultrasound device is affordable and does not add significant additional time to the procedure. It is also an essential tool for training new surgeons on this procedure safely. Ultrasound guidance is an efficacious adjunct to gluteal fat grafting and is associated with an improved safety profile that should be considered by every surgeon performing this procedure.

Supplemental Material

This article contains supplemental material located online at www.aestheticsurgeryjournal.com.

Disclosures

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

REFERENCES

International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (ISAPS) International survey on aesthetic/cosmetic procedures performed in 2021. Accessed November 13, 2023. https://www.isaps.org/media/vdpdanke/isaps-global-survey_2021.pdf

Multi-Society Gluteal Fat Grafting Task Force issues safety advisory using practitioners to reevaluate technique. Accessed July 10, 2023. https://www.surgery.org/sites/default/files/Gluteal-Fat-Grafting-02-06-18_0.pdf

Florida House Bill 1471: Health Care Provider Accountability Act. Accessed November 13, 2023. https://www.flsenate.gov/Session/Bill/2023/1471/?20Tab=VoteHistory

Author notes

Drs Vidal-Laureano and Earle are plastic surgeons in private practice in Miami, FL, USA.

Drs Huerta and Perez are general surgeons, Department of Surgery, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, FL, USA.

- ischemia

- ultrasonography

- postoperative complications

- anesthesia, general

- catheterization

- comorbidity

- fat embolism

- esthetics

- intramuscular injections

- safety

- surgical procedures, operative

- surgical wound infection

- mortality

- skin

- plastic surgery specialty

- wound seroma

- fat transplantation

- ultrasonic guidance procedure

- transfer technique

- lipomodeling