-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Ryan Faderani, Prateush Singh, Massimo Monks, Shivani Dhar, Eva Krumhuber, Ash Mosahebi, Allan Ponniah, Facial Aesthetic Ideals: A Literature Summary of Supporting Evidence, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 44, Issue 1, January 2024, Pages NP1–NP15, https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjad295

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

To achieve the goal of enhancing facial beauty it is crucial for aesthetic physicians and plastic surgeons to have a deep understanding of aesthetic ideals. Although numerous aesthetic criteria have been proposed over the years, there is a lack of empirical analysis supporting many of these standards.

This aim of this review was to undertake the first exploration of the empirical evidence concerning the aesthetic ideals of the face in the existing literature.

A comprehensive search in MEDLINE, Embase, Scopus and CENTRAL databases was conducted for primary clinical studies reporting on the classification of the facial aesthetic units as per the Gonzales-Ulloa facial aesthetic unit classification from January 1962 to November 2022.

A total of 36 articles were included in the final review: 12 case series, 14 cohort studies, and 10 comparative studies. These described the aesthetic ideals of the following areas: forehead (6 studies; mean level of evidence, 3.33); nose (9 studies; mean level of evidence, 3.6); orbit (6 studies; mean level of evidence, 3); cheek (4 studies; mean level of evidence, 4.07); lips (6 studies; mean level of evidence, 3.33); chin (4 studies; mean level of evidence, 3.75); ear (1 study; level of evidence, 4).

The units that were most extensively studied were the nose, forehead, and lip, and these studies also appeared in journals with higher impact factors than other subunits. Conversely, the chin and ear subunits had the fewest studies conducted on them and had lower impact factors. To provide a useful resource for readers, it would be prudent to identify and discuss influential papers for each subunit.

Recognition of facial beauty is a reflexive and universal phenomenon that occurs instantaneously. Our ability to instinctively identify and appreciate facial beauty without consciously unraveling the underlying cognitive processes or reasoning behind it remains a mystery.1 Artists, mathematicians, and surgeons have, throughout history, dedicated themselves to studying this phenomenon in an effort to unravel the secrets behind facial beauty recognition and its defining factors. The challenge of objectively defining the parameters of beauty dates back centuries, with ancient Greece providing clear documentation of its significance. The Greeks firmly believed that beauty was a result of ideal proportions. Aristotle famously described beauty as “a sense of harmonious or aesthetically pleasing proportionality.” It was during this flourishing period of Greek philosophy around 500 BC that various arithmetic principles emerged, such as the 1:1 “unity” ratio, the division of the face into thirds, and the concept of the golden ratio. These principles aimed to provide insights into the foundations of facial beauty.2,3

During the Renaissance, the Euclidean concept of the golden ratio was further developed into the notion of the “divine proportion” by Luca Pacioli and Leonardo da Vinci.4-6 Their work explored the applications of the golden ratio in geometry, architecture, and the natural world, including the human face. This fusion of mathematics, art, and geometry led to the formulation of the early canons of facial aesthetics. In this period of experimentation, various facial indices were introduced, such as the classical facial index, the Bruges facial index, and the Vitruvian proportions in the lower face.2,7,8 Even in contemporary aesthetics, the golden ratio continues to inspire research in the field of facial aesthetics.9 One prominent advocate of the golden ratio, Marquardt, conducted cross-cultural surveys on beauty, both in modern and historical contexts.10 His research led him to conclude that beauty is a result of the golden ratio, which remains consistent across genders, races, and cultures. Based on this belief, Marquardt developed the controversial “Marquardt mask” as a means to determine optimal beauty. The mask is derived from the application of the “golden decagon matrix,” which is created by applying the golden ratio to human faces.10 However, similar to previous attempts at defining beauty, this “one mask fits all” approach has also proven inadequate in accurately predicting or modeling facial aesthetics.11,12

In the twentieth century, the field of facial anthropometry saw significant advancements due to the contributions of surgeons such as Seghers, Farkas, and Ricketts.13-16 Their research involved conducting direct measurements of facial features in both attractive and unattractive individuals, aiming to compare and establish standard values for attractive facial features. Their findings challenged the notion that aesthetic ideals were solely based on the golden ratio. They emphasized that there are multiple components contributing to facial attractiveness beyond mere proportions. Their work revealed that facial beauty arises from the interplay of various factors, including symmetry, averageness, ogee curves (S-shaped curves), measurements of individual subunit features, and overall proportions.17 A face that harmoniously incorporates these elements adheres to a global standard of beauty, which has been observed to be consistent across different ethnicities and cultures.

As aesthetic physicians and plastic surgeons, our responsibility is to enhance the natural beauty of our patients’ faces, whether this is for aesthetic enhancement or for reconstructive purposes. To achieve this goal, it is crucial for us to have a deep understanding of the aesthetic ideals that we strive to achieve. Although numerous aesthetic criteria have been proposed over the years, there is a lack of empirical analysis supporting many of these standards. Therefore, it is essential to have a comprehensive and concise comprehension of the quantitative evidence related to aesthetic standards. This knowledge will enable practitioners to optimize their outcomes and introduce objectivity into our field. To the best of our knowledge, this literature review represents the first exploration of the empirical evidence concerning the aesthetic ideals of the face in the existing literature.

METHODS

Search Strategies

A comprehensive, systematic literature search of published articles was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines.18 The search collected articles published from January 1962 until November 2022.

The literature search was performed in the MEDLINE (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD), Embase (Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands), Scopus (Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands), and CENTRAL (Wiley, Hoboken, NJ) databases. The keywords used in the search were selected from key papers; 2 search strings were created and combined with the Boolean term “AND”. Additionally, a MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) term search was also conducted. Forwards and backwards citation searching, as well as gray literature, was checked to identify further articles. A search was carried out for each of the aesthetic subunits as per the Gonzales-Ulloa facial aesthetic unit classification.19

String 1: “Face” OR “Forehead” OR “Nose” OR “Eyelid” OR “Cheek” OR “Upper lip” OR “Lower lip” OR “Chin” OR “Ear” AND “Aesthetic” OR “beauty”

String 2: “Classification” OR “Analysis” OR “Measurement” OR “Anthropometry” OR “Ideal*”

Inclusion Criteria

Original research publications, including randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, case-control studies, and case series which reported on the aesthetic classification of at least 1 facial unit

Human female subjects

Exclusion Criteria

Studies reporting on the measurement of facial units without providing aesthetic ideals

Studies with only male subjects

Review articles

Conference abstracts without full text

Case reports

Non–English language studies

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measure was the presentation of data related to aesthetic classification of facial subunits.

Study Selection and Data Management

Study selection was conducted in a 2-stage process. Titles and abstracts were initially screened by 2 reviewers (R.F. and P.S.) for potential eligibility, after excluding duplicate records. Next, studies identified as relevant underwent full-text review by both reviewers. Any discrepancies between the reviewers were resolved by discussion or referral to a third reviewer (A.P.). The data from all full-text articles accepted for the final analysis were independently retrieved by R.F. and P.S. by means of a standardized data-extraction form. Any discrepancies between the reviewers were resolved by discussion or referral to A.P. All data were then reviewed by A.P. The search results, including abstracts, full-text articles, and records of reviewers’ decisions, including reasons for exclusion, were recorded in Endnote X8 (Clarivate Analytics).

The extracted data include details on study characteristics, number of patients, classification used, methodology, study objectives, outcomes, and ideals listed. Data were extracted from the studies as presented.

RESULTS

Literature Search Results

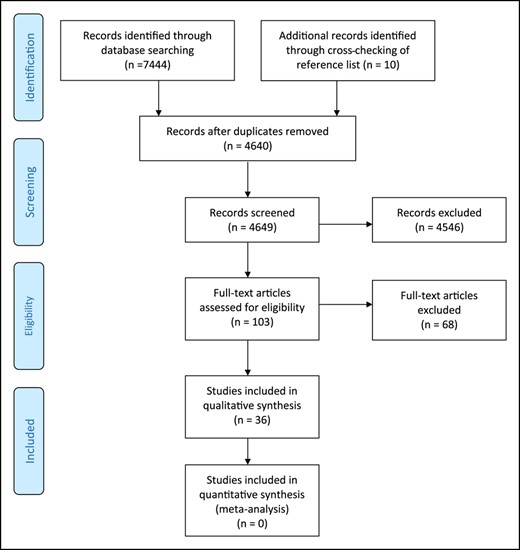

We found 2773 articles in the MEDLINE database search, 2739 articles in the Embase database search, 1760 in the Scopus database search, and 172 in the CENTRAL database search. References from these 4 searches were combined, and after removing the duplicates, 4640 articles were available for title and abstract reviewing. Of these, 4546 articles did not meet the inclusion criteria and were excluded. Following full-text review of the remaining 94 articles, 68 articles were excluded as the inclusion criteria were not met. A secondary search of the reference list revealed an additional 10 articles. A total of 36 articles were included in the final review and formed the basis of this systematic review (Figure 1). Details of the included studies are summarized in Supplemental Table 1. There were 12 case series, 14 cohort studies, and 10 comparative studies. The mean level of evidence of the studies included in this review was 3.29.

The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram.

Forehead

We identified 6 studies that described the aesthetic ideals of the forehead. The mean level of evidence for this unit is 3.33. The mean impact factor of the journals in which these studies were published is 4.09.

Nose

We identified 9 studies that described the aesthetic ideals of the nose. The mean level of evidence for this unit was 3.33. The mean impact factor of the journals in which these studies were published is 3.60.

Orbit

We identified 6 studies that described the aesthetic ideals of the periorbital unit. The mean level of evidence for this unit was 3. The mean impact factor of the journals in which these studies were published is 1.82.

Malar

We identified 4 studies that described the aesthetic ideals of the malar unit. The mean level of evidence for this unit was 3.25. The mean impact factor of the journals in which these studies were published is 4.07.

Lip

We identified 6 studies that described the aesthetic ideals of the lip unit. The mean level of evidence for this unit was 3.33. The mean impact factor of the journals in which these studies were published is 3.40.

Chin

We identified 4 studies that described the aesthetic ideals of the chin unit. The mean level of evidence for this unit was 3.75. The mean impact factor of the journals in which these studies were published is 1.95.

Ear

We identified 1 study that described the aesthetic ideals of the ear unit. The level of evidence for this study was 4. The impact factor of the journal in which this study was published is 2.08.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of conducting this literature review was to gather and analyze the existing evidence regarding the aesthetic standards of different facial subunits. It is not surprising that some subunits received more attention than others from researchers. The subunits that were most extensively studied were the nose, forehead, and lip, and the journals reporting these studies also had higher impact factors than journals reporting studies on the other subunits. Conversely, the chin and ear subunits had the fewest studies conducted on them, and these studies appeared in journals with lower impact factors. Interestingly, despite the periorbital area being the subject of a large number of studies, these studies were found in journals with the lowest average impact factors. It was also notable that the majority of studies on the periorbital area were conducted in East Asia, whereas studies on other facial units were predominantly carried out in Western regions, emphasizing the cultural significance attached to certain facial subunits. Meta-analyzing all the studies in a quantifiable way presents a challenge due to significant heterogeneity in the methodology of the papers and the various measurements used in defining aesthetic standards. This heterogeneity includes the use of different metrics, proportions, degrees, coordinates, and descriptions. Furthermore, authors utilized various methods to compare attractive and less attractive faces, including evaluating fashion models, grouping faces into attractive and unattractive categories by nonmedical study participants, having professional make-up artists rank attractiveness, and the authors themselves ranking attractiveness.

As a result, it becomes challenging to combine the results of different studies into a single, quantifiable analysis. Our comprehensive search yielded numerous aesthetic classifications for each facial subunit. To provide a useful resource for readers, we believe it would be prudent to identify and discuss influential papers for each subunit. By doing so, readers can refer to these papers as a reference point for further investigation and analysis.

Forehead

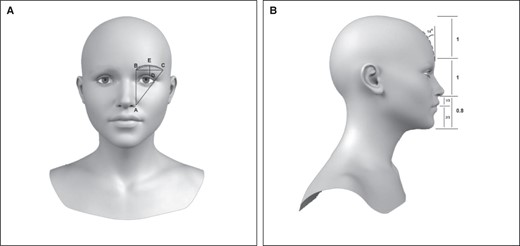

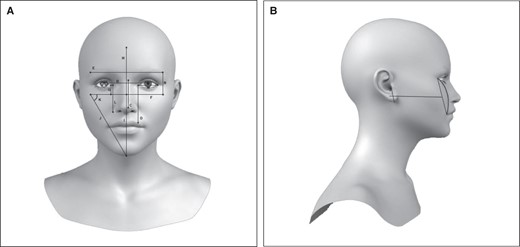

The forehead aesthetic unit can be subdivided into 3 subunits: central forehead, lateral forehead (temple), and brow (Figure 2).19,20

(A) Westmore brow. (A) Ala; (B) Medial brow; (C) Lateral brow; (AC) Oblique line drawn from ala through the lateral canthus to lateral brow; (D) Lateral limbus; (E) Brow apex. (B) Forehead length and angle.

Eyebrows

Most of the studies that investigated the aesthetic standards of the forehead focused on defining the standards for the eyebrow. The aesthetics of the eyebrow have evolved over the years, with fashion trends playing a significant role in shaping standards. One of the earliest definitions of a modern aesthetic ideal for the brow was provided by Westmore (Figure 2A).21 However, it is important to note that this definition did not provide any numerical guidelines for the brow. Instead, it was based solely on Westmore's aesthetic ideals, without any empirical evidence to support his suggestion.

Gunter and Antrobus conducted a study to explore the relevance of eyebrow shape in facial aesthetics.22 In their study, the authors compared the difference in brow shape between a group of “attractive” models from fashion magazines and a second group of patients from their practice who were consulted for facial rejuvenation procedures (many of whom underwent brow lifts). They suggested that when evaluating eyebrow aesthetics, it is important to consider the entire periorbital area, especially the eyelids. By doing so, one can better understand the impact of the brow shape on the overall appearance of the eyes and surrounding areas.

Another important consideration in evaluating eyebrow aesthetics is the patient's facial shape. It has been suggested that although the Westmore brow is considered the most aesthetically appealing in an oval face shape, this may not necessarily be the case for individuals with rounder, squarer, or longer faces.23 Therefore, it is important for practitioners to consider each patient's individual facial features and characteristics when determining the most appropriate brow shape and aesthetic ideal.

Forehead Length

The ideal vertical height of the forehead is also an important consideration in facial anthropometry and aesthetics. Studies have shown that elongation of the forehead can negatively impact facial attractiveness.24 Several studies have suggested that the ideal forehead height (measured from brow to hairline) in females should be between 5 and 6 cm.15,25,26 These studies determined the ideal height based on the concept of averageness, where anthropometric measurements of forehead length were obtained from a population of “average” individuals. In addition to metric measurements for forehead length, there are several ideal proportions to consider when assessing facial aesthetics. One of the most widely used canons over the centuries has been the division of the face into horizontal thirds. Leonardo da Vinci described the canon of equal thirds, which states that the following 3 measurements should be equal: the upper third (trichion to glabella), the middle third (glabella to subnasale), and the lower third (subnasale to menton)27 (Figure 2B). Studies have shown that attractive females generally meet the criteria of these proportions in terms of their facial parameters.27

Forehead Inclination

Forehead inclination is a measure of the lateral contour of the forehead, defined as the angle between the line from the trichion to the glabella when the face is placed on the Frankfort horizontal line (Figure 2B).28 In a study of 100 Korean women, Oh et al found that the mean forehead inclination was 12.47° (range, 11.6°-13.3°).29 This study, however, did not focus on determining the most attractive forehead inclination. Instead, it emphasized the potential significance of considering forehead inclination as a factor in assessing attractiveness. Furthermore, it highlights the importance of recognizing and accounting for racial variations in facial structure and aesthetic preferences. Swift and Jones suggested that a beautiful female forehead has a curve of 12° to 14° recession off the vertical axis (which they depicted graphically).9 Although this measurement is important to consider, there are no studies comparing the curve of the forehead in attractive and unattractive faces.

Nose

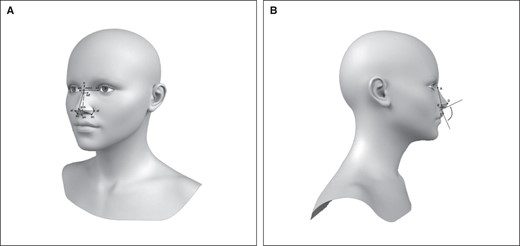

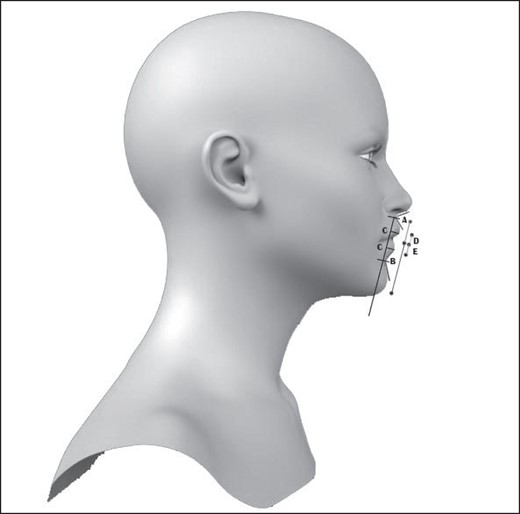

The nose, as the central feature of every face, plays a crucial role in determining overall facial beauty among facial units. However, due to the complex 3-dimensional morphology of the nose and its central role in aesthetics, many potential ideals for nasal aesthetics have been suggested. To quantify nasal dimensions, several measurements can be taken into account, including height, width, and inclinations such as nasal tip projection, nasolabial angle, and nasofrontal angle. Additionally, nasal proportions such as nose width/nose height, nose height/face height, and nose width/face width are also considered. (Figure 3)

(A) Nasal measurements as per Farkas: nose height (n-sn dotted), nasal bridge length (n-prn), nasal root depth (sagittal) (m(s)), nasal root width (horizontal) (mf-mf), nasal root slope length (m-en), soft nasal tip protrusion (sn-prn), soft nose width (al-al), ala length (ac-prn). (B) Combination of nasolabial angle and Crumley 1 method for defining nasal tip projection. (A) Vertex of nasofrontal angle; (B) perpendicular from line (AE) through (D); (D) tip defining point; (E) vermilion-cutaneous junction of upper lip.

Interalar-Intercanthal Ratio

To determine the quantitative parameters of the ideal nose, Farkas et al conducted a study comparing anthropometric nasal and craniofacial measurements between attractive and below-average faces of young North American Caucasian women.30 The study included 34 attractive women and 21 “below average” faces from a group of 200 women, and various nasal and craniofacial parameters were measured and compared. This paper is considered one of the earliest and most influential works in this field. However, the authors did not specify how the attractiveness groups were determined in the study. Farkas et al not only emphasized the absence of 6 neoclassical canons, namely the 3-section profile canon, nasoaural canon, orbitonasal canon, nasofacial canon, naso-oral canon, and nasoaural inclination canon, in aesthetically pleasing noses, but also presented a detailed quantitative analysis of the dimensions, angles, and proportions of the aesthetically pleasing nose. This analysis was backed by numerical data and measurements.30 The orbitonasal canon, which is one of the earliest canons, proposes that the distance between the nostrils (interalar distance) should be equivalent to the distance between the inner corners of the eyes (intercanthal distance).31 However, Baker et al conducted a study to determine the optimal alar width and measured this ratio in 36 Caucasian females who were objectively rated as the “most beautiful women” by People Magazine. Their findings indicated that the ideal interalar distance for aesthetic purposes is slightly wider than the intercanthal distance, with a ratio of 1:1.17.32

Nasal Tip Projection

Nasal tip projection (NTP) refers to the forward extent of the nasal tip from the facial surface, which is most prominently observed in profile view. NTP is considered to be one of the most critical aspects of both nasal aesthetics and rhinoplasty procedures. The earliest and most frequently referenced method for measuring NTP was established by Goode, who determined it as a ratio calculated by dividing nasal height by nasal length. According to Goode, the optimal NTP range is between 0.55 and 0.6. Since then, several other techniques for measuring NTP have been proposed, such as the Simons, Baum, Powell, and Crumley ratios.33-36

Numerous researchers have since attempted to examine the relationship between facial attractiveness and the different methods of NTP measurement. These studies applied various NTP measurement techniques to facial images, which were subsequently assessed for attractiveness. The level of correlation between the different NTP measurement methods and facial attractiveness was then evaluated.

The Crumley methods (Crumley 1 and 2) demonstrate the strongest correlation with facial attractiveness.33,37,38 The Crumley 1 method calculates NTP by dividing the sum of upper lip length and nasal length by nasal height, whereas the Crumley 2 method determines NTP by dividing the distance from the vertex of the nasofrontal angle to the menton by nasal height. Crumley has suggested that the optimal NTP is 3.53 based on the Crumley 1 method and 4.23 based on the Crumley 2 method.

Nasolabial Angle

The available literature provides different methods of measuring the nasolabial angle (NLA), with 4 commonly used definitions: (1) the angle between the columella and the line that intersects the subnasale and labrale superius; (2) the angle between the columella and the line tangent to the cutaneous upper lip proper; (3) the angle between the long axis of the nostril and the line perpendicular to the Frankfort horizontal; and (4) the angle between the long axis of the nostril and the line that intersects the glabella and pogonion.30,37-39 However, no studies have compared the aesthetic relevance of these various definitions. In a survey of 82 rhinoplasty surgeons, Harris et al found that there is no consensus among surgeons regarding the optimal definition of NLA.40 We identified 2 studies that have attempted to calculate the ideal NLA empirically.

Sinno et al defined NLA as the angle between the columella and the line tangent to the cutaneous upper lip proper.38 They conducted a study in which 98 members of the public rated the aesthetic appeal of 3 different nasolabial angles (100°, 105°, 110°) and concluded that the most aesthetically pleasing NLA was 104.9°. On the other hand, Armijo et al defined NLA as the angle between the long axis of the nostril and the line perpendicular to the Frankfort horizontal.41 They manipulated lateral photographs of 10 women to have various nasolabial angles (90°-110°) and then had plastic surgery residents and office staff rate these photographs. Their study suggested that the ideal nasolabial angle would be 97.7° ± 2.32° with a range of 95.56° to 100°. It is worth noting that each definition of NLA has its advantages and disadvantages.

The method described by Sinno et al considers the surface anatomy of the patient, which can lead to a better understanding of each patient's aesthetic preferences.38 However, this method can be distorted by underlying bone or soft tissue abnormalities such as upper lip fillers or implants, upper lip deficiency, Class II malocclusion, protrusive maxilla, and upper incisor inclination. In contrast, measuring NLA using a line perpendicular to the Frankfort horizontal or a line intersecting the glabella and pogonion is governed by a facial plane, and therefore the bony structures play a larger role in defining the NLA than the soft tissues. These measurements are more constant over time and less likely to be altered, but they are more difficult to make in person and do not consider the labial component of the angle. For aesthetic surgeons, it is important to choose the definition of NLA that is most appropriate for their patient. Additionally, when making comparisons of proposed aesthetic ideals, it is essential to consider how the studies have measured NLA to avoid discrepancies. In summary, the choice of NLA definition should be made based on each patient's individual characteristics and the surgeon's preferences. The advantages and disadvantages of each definition should be taken into account when selecting the most appropriate method, and comparisons between studies should be made with caution.

Orbit

The eyes and periorbital area are crucial in determining facial attractiveness and are often the first areas to display signs of aging. Ethnic differences in the morphology of this region also exist, further highlighting the importance of individualized treatment approaches. The primary objective of surgery in this region is typically to restore a more youthful appearance. To accomplish this goal, several measurements must be taken into account. These measurements may include the degree of brow ptosis, the amount of upper eyelid skin redundancy (excess skin), the amount of orbital fat prolapse, and the degree of lower eyelid malposition (drooping or bulging of the lower eyelid).

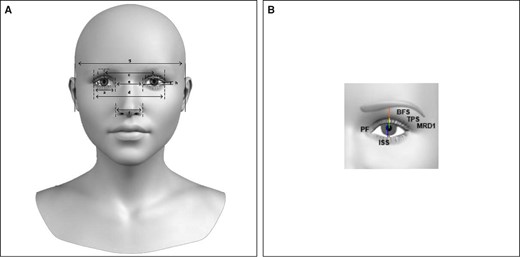

Canthal Tilt

Canthal tilt is defined as the angle between the horizontal line from the medial to the lateral canthus and is considered an important factor in determining facial aesthetics (Figure 4). Although a positive canthal tilt is generally preferred, there is still debate regarding the ideal degree of tilt. Research conducted by Kim et al, who measured anthropometric data in a group of 43 Korean beauty pageant models, suggested that the ideal canthal tilt for Korean women is around 8°.42 Similarly, Rhee et al found that a canthal tilt of 8° was desirable in Korean women, while noting that Caucasian women typically have a lower average canthal tilt of 4.12°.43 These findings highlight the importance of taking into account the ethnic background of the population being studied in determining aesthetic ideals of the orbital area.42,44 It is essential to understand and appreciate the cultural, racial, and gender-based anatomic differences between populations to achieve optimal outcomes in facial plastic surgery.

(A) Anthropometric measurements, frontal view: (a) horizontal dimension of palpebral fissure (exocanthion-endocanthion); (b) vertical dimension of palpebral fissure (palpebrale superius–palpebrale inferius); (c) interpupillary distance (center of pupil–center of pupil); (d) binocular width (exocanthion-exocanthion); (e) intercanthal width (endocanthion-endocanthion); (f) nasal width (distance between the widest point on each ala); (g) midfacial width (tragus-tragus); (h) slant of palpebral fissure (angle of the line between endocanthion and exocanthion of an eye based on the line connecting the right and left endocanthion); (i) height of upper eyelid (perpendicular distance between palpebrale superius and lower margin of the eyebrow); (j) width of pretarsal crease (palpebrale superius–upper margin of crease). (B) Eyelid measurements: brow fat span (BFS), red line; tarsal platform show (TPS), yellow line; margin to reflex distance 1 (MRD1), green line; palpebral fissure (PF), blue line; inferior scleral show (ISS), pink line.

Upper Eyelid

The upper eyelid varies greatly among different ethnicities and is the focus of many procedures. One of the key differences between ethnicities is the presence of a supratarsal crease. The supratarsal crease is the fold of skin in between the brow fat span and the tarsal platform show. Numerous studies have delved into the exploration of aesthetic ideals specifically within East Asian populations, shedding light on the significance of the supratarsal crease in defining an aesthetically pleasing eye.42,45,46 In their research, Rhee et al brought attention to the differing characteristics of the supratarsal crease among various ethnic groups.43 They found that in Caucasian individuals, a lower-positioned supratarsal crease tends to impart a more natural and youthful appearance. On the other hand, in Korea, a higher-positioned supratarsal crease without an epicanthal fold is considered preferable, while in Japan, a higher-positioned supratarsal crease with the presence of an epicanthal fold is favored.43 Vaca et al explored the topographic variations of upper eyelid proportions among Caucasian females: 294 individuals were evaluated for their eye “attractiveness” by a panel of 6 members comprising both plastic surgeons and laypersons.47 The authors conducted a comparison between eyes categorized as “attractive” and “unattractive.” They specifically directed their attention towards assessing the ratio between the upper lid fold (the crease of the eyelid to the lower margin of the brow) and the pretarsal region (area from lash line to eyelid crease) at multiple positions. The authors illustrated elevated ratios in attractive eyes compared with less attractive ones. Furthermore, they emphasized earlier observations indicating a stronger connection between positive canthal tilt and attractive eyes. The authors also investigated the link between the golden spiral and upper lid aesthetics. They discovered that the curvature peaks of attractive eyes aligned more closely with the golden spiral compared with less attractive eyes. However, this observation did not attain statistical significance, underscoring the tendency of conventional standards to come up short under empirical examination. These findings further emphasize the crucial importance for surgeons to recognize and consider the influence of ethnicity on beauty ideals when planning aesthetic procedures involving the periorbital region. By acknowledging these ethnic nuances, surgeons can tailor their approaches and techniques to achieve results that align with the aesthetic preferences and cultural norms specific to each ethnic group.

Tarsal platform show refers to the distance between the upper eyelash and the supratarsal crease (Figure 4). In a study conducted by McDonnell et al, 110 individuals were asked to rate 42 Caucasian faces. These faces were divided into 2 categories, “attractive” and “unattractive,” by laypeople. The researchers measured various eyelid parameters and compared the differences between these 2 groups. The study revealed that the tarsal platform show was lower in the group perceived as aesthetically pleasing, with a mean [standard deviation] measurement of 2.97 [0.9] mm.44

Lower Eyelid

The morphology of the lower eyelid exhibits considerably less variation than that of the upper eyelid. Currently, there is a lack of empirical studies that specifically classify the aesthetic ideal of the lower lid. However, one prominent reason for undergoing lower lid surgery is the age-related lengthening of the lower lid. A crucial measurement utilized to define the lower eyelid is the vertical distance from the lower eyelid margin to the lower lid crease in the midpupillary line, as outlined by Fezza and Massry.48 In their research, Fezza and Massry demonstrated a strong linear correlation between age and lower lid length. This measurement plays a significant role in assessing the youthfulness of the lower eyelid region and thereby influences the aesthetic ideal associated with it.48

Cheek/Malar

The intricacy of the subtle curvature found in the malar region poses a challenge when attempting to define it quantitatively. The interplay of facial shadows and highlights plays a significant role in creating the desirable curves associated with a youthful face. Existing literature acknowledges the limitations of analyzing the malar region solely through anterior and lateral views, suggesting that an oblique angle is necessary.49 Addressing the aging midface is a critical aspect of facial rejuvenation, as it often involves a loss of malar projection, resulting in a disruption of the youthful ogee curves. The concept of the malar ogee curve was first introduced by Little.50 He emphasized that when observing a face from an oblique angle, the soft tissues in the midface form an architectural S-shaped curve. Little described the ideal malar ogee curve as an elegant transition starting from the lateral tail of the brow, flowing through the convex fullness of the cheek, and tapering into the concave contour of the mandibular border. This configuration creates a harmonious and aesthetically pleasing appearance.

Ogee Curve

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the malar area, it is essential to consider the relationship between the ogee curves and the key landmarks within the midface. These landmarks include the malar eminence, zygomatic point, malar hollow, and the anterior and posterior mandible.49,51 The configuration and alignment of these landmarks contribute to shaping the overall appearance of the midface. However, it is worth noting that only a limited number of studies have successfully established parameters for aesthetically classifying the midface. These studies have attempted to quantify the relationship between landmark points by measuring lengths from the midline, employing coordinates, or calculating distances from reference lines (such as the lateral canthus to oral commissure or interzygomatic distance). Additionally, some early studies have presented aesthetic ideals by defining specific facial coordinates in frontal, lateral, and oblique views. Although these approaches are intriguing, they present challenges when it comes to their practical application in current clinical practice.

WIZDOM

Linkov et al introduced the WIZDOM (width of the interzygomatic distance of the midface) parameter as a valuable tool for assessing the relationship between midface landmarks (Figure 5).52 By drawing a horizontal line connecting the zygomaxillary points on both sides of the face, the authors were able to measure various distances and relationships between this line and multiple facial landmarks, including the chin, medial canthus, and lateral brow. In their study, the authors assessed the faces of 55 attractive models and developed the WIZDOM parameter, aiming to identify aesthetic ideal parameters for the midface. The results demonstrated that WIZDOM is a reliable and straightforward tool that can be utilized to define the midface in 2-dimensional photographs. By using this tool, clinicians and researchers can objectively assess and quantify the relationship between midface landmarks, providing valuable insights into the aesthetics of the midface region.

(A) WIZDOM (width of the interzygomatic distance of the midface) parameter: (A) corneal diameter; (B) interpupillary distance; (C) nasal length; (D) medial canthus; (E) brow length; (F) WIZDOM; (G) WIZDOM to medial canthus; (H) hairline to WIZDOM; (I) chin to WIZDOM; (J) chin to WIZDOM diagonal; (K) angle to WIZDOM; (L) medial canthus to nasal ala; (M) eye length; (N) lateral brow to WIZDOM. (B) Beauty arch.

Beauty Arch

The concept of the “beauty arch” offers another valuable approach to analyze lateral malar projection. This method was developed by Marianetti et al as a means to determine the ideal position of the zygomatic prominence in the sagittal view.53 In this technique, an arch is constructed in lateral view by drawing a line from the lateral canthus to the edge of the mouth. From the midpoint of this line, a perpendicular line known as the fulcra line is drawn. The fulcra line intersects with a perpendicular line passing through the lateral canthus. Using this intersection point, a compass is utilized to create an arch that passes through the corner of the mouth. This resulting arch is referred to as the beauty arch. Although this method can be complex and challenging to perform on a patient, it was developed based on a study involving 74 “attractive” beauty contestants. The beauty arch has been effectively used in planning malar augmentation for individuals with malar hypoplasia, demonstrating its utility in midfacial reconstruction. Although it may require technical proficiency, this approach provides valuable guidance for achieving desirable malar projection and aesthetics in appropriate cases.

Lips

Historically, plump lips have been associated with a youthful appearance and have been considered aesthetically desirable. Moreover, efforts have been made to objectively analyze and establish standards for rejuvenation and aesthetic evaluation.

In 1984, Farkas et al conducted a study focusing on the proportions of average faces, aiming to establish standards for defining the dimensions of the upper lip, lower lip, and chin area.54 However, it is worth noting that this study did not specifically address the concept of facial attractiveness. Our investigation highlighted that in perioral aesthetics, several measurements need to be considered. When examining the frontal face, it is important to measure the upper lip and lower lip heights, as well as the distances from the nasal tip to the mouth and from the mouth to the chin. These measurements can be used to formulate several proportions such as the upper lip to lower lip ratio, upper lip height to nose–mouth ratio, and the lower lip height to mouth–chin ratio (Figure 6).54-56

Lip analysis: nasolabial angle (red), mentolabial angle (green), lip protrusion (black), upper lip height (pink), lower lip height (orange).

Talei and Pearlman present a noteworthy study, which outlines a comprehensive methodology for characterizing the upper lip and offering guidance on preserving a youthful lip balance through surgery.57 Although their study lacks a direct comparison between attractive and unattractive lips in terms of empirical aesthetic ideals, it does offer valuable insights into essential factors for approaching a lip lift. The authors introduce the innovative “CUPID lip lift” technique, which effectively preserved the natural upper lip balance, enhanced muscle function, and ensured favorable long-term results in a cohort of 2440 consecutive patients spanning 6 years.

Upper-Lower Lip Ratio

The ideal ratio between the upper lip and lower lip is a subject of considerable debate in perioral aesthetics. Various studies suggest a range of ideals, spanning from 1:1 to 1:2.53,55,58 Among these, Bisson and Grobbelaar's research provides the most commonly referenced ideal for the upper to lower lip ratio. In their study, they compared the aesthetic characteristics of lips between 28 fashion models and 14 hospital employees.59 Based on their measurements, they proposed an upper lip to lower lip ratio of 1:1.6.59 Additionally, they observed that both the upper and lower lip heights were greater in models than the general population. Interestingly, Heidekrueger et al, in a cross-cultural survey, found that lip ratio preferences did not differ significantly across different ethnicities. However, they did note variations between age groups within the same ethnicity, with younger individuals showing a preference for larger lower lips.60

Philtrum: Labial Parameters

Similar to the lower eyelid, the elongation of the upper lip over time due to gravitational effects and reduced elasticity of the soft tissues can cause an abnormal balance between the upper lip height and the nose-mouth distance. To better analyze the upper lip region, Raphael et al developed the philtral-labial score (PLS).56 To calculate the PLS, 3 important landmarks need to be identified with the lips touching at rest: the base of columella (subnasale), the midpoint of the superior vermilion border (labiale superius), and the center of the labial fissure (stomion). These landmarks are then used to define the philtral and labial heights. The PLS is calculated by dividing the philtral height by the labial height. The authors show that with the aging process, the PLS increases over time, and larger PLS values are considered less attractive, with an ideal score of 2.0. Ultimately, this score serves as a measure of lower face disharmony and is a useful tool in defining the aesthetics of the upper lip.56

Lip Protrusion

Lip protrusion refers to the point of maximum projection of the lip, as measured in lateral view. To calculate lip protrusion, the point of maximum protrusion of the vermillion is measured on a side view, perpendicular from a vertical line connecting the base of the columella to the fold demarcating the lower lip and chin, as outlined by Lemperle et al.61 In addition to lip protrusion, the nasolabial and mentolabial angles are useful measures in defining the protrusion of the upper and lower lips.58,59 Penna et al found that when comparing the nasolabial and mentolabial angles in “attractive” and “unattractive” patients (judged by online volunteers through a survey), both angles were significantly less in the attractive cohort.56 Specifically, they found that a nasolabial angle of 98° and a mentolabial angle of 130.5° were most attractive in this group.56

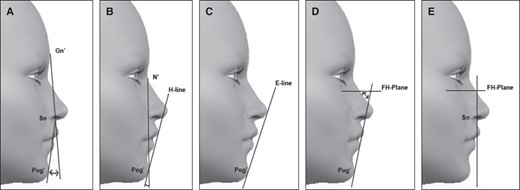

Chin

Extensive exploration of the chin's cephalometric analysis has been carried out within the field of orthodontics. Numerous methods have been developed to measure the degree of anteroposterior mandibular protrusion (Figure 7).14,62,63 However, only a limited number of studies have specifically examined the aesthetically appealing positions of the chin. Kuroda et al determined that, among the Japanese population, faces with a degree of mandibular retrusion were considered most attractive, and this finding correlated well with the Burstone Sn-Pog (subnasal-poganion) classification.64 When comparing the correlation of different methods of chin protrusion analysis to facial attractiveness, significant cultural differences emerge regarding the preferred method.64 Hsu suggested that the Burstone Sn-Pog line is best suited for aesthetic analysis of profiles in the Chinese population as well.65 However, in studies conducted on the Turkish population, Ricketts’s norms for upper and lower lips appeared to exhibit a stronger correlation.66 This again highlights the need to take into consideration cross-racial differences for facial aesthetics. Notably, there are currently no studies comparing methods of analysis specifically within the Caucasian population group (Figure 7).

Different methods of soft tissue analysis: (A) Legan and Burstone analysis; (B) Holdaway Analysis (H Line); (C) Ricketts profileanalysis; (D) Merrifield Z-Angle; (E) Epker soft tissue relationships. E-line, Line through Pogonion and nasal tip; FH-Plane, Frankfurt Horizontal; Gn, Glabellar; H, Holdaway soft tissue line; N, Nasion; Pog, Pogonion; Sn, Subnasale.

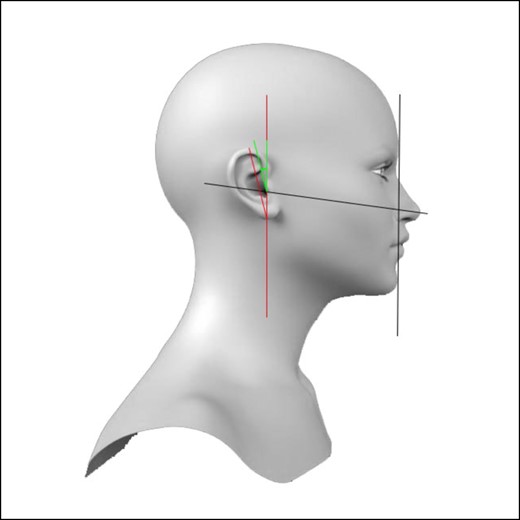

Ear

Although there have been numerous studies analyzing the dimensions of the ear during growth, there is a lack of research specifically focused on empirically defining aesthetic ideals for the ear.67 From a lateral facial view, ear position is defined by the angle of the ear axis in relation to a true vertical line of the face extending from nasion to gonion (Figure 8). Previous work by Farkas indicated that the normal range of auricular inclination fell between 9° and 29°.67 However, Broer et al emphasized that the ideal ear position is slightly reclined, ranging from −5° to 10°.68 Broer et al conducted an online survey among plastic surgeons and the general public worldwide.68 Participants were asked to modify the axis of a female model's ear to align with their desired ideal. Furthermore, they discovered that participants’ country of residence influenced ear axis preferences, with European participants tending to prefer a more vertical ear compared with those from the Middle East. Clearly, the ear unit has received limited attention in terms of defining aesthetic ideals, indicating a need for further research in this area to establish standards for the aesthetically pleasing ear.

The ear axis. Green line is the angle of the ear axis with respect to the true vertical of the face (red and black lines, axis from nasion to gonion).

The Future of Defining Facial Aesthetics

The majority of papers encompassed within this study employed manual facial measurements and deliberate evaluations of facial aesthetics carried out by both surgeons and volunteers. This approach can be labor-intensive, susceptible to error, and constrained by the number of faces that can feasibly be assessed. Given advancements in artificial intelligence capabilities, the future of delineating aesthetic standards may rest within artificial intelligence models. Specifically, there is promise in developing a system proficient in illustrating the perspectives observed when appraising a face, while simultaneously aiding in definition of facial beauty. This can be accomplished through the synergistic integration of computer vision, machine learning, and cognitive psychology. Such a system would be able to provide insights into the manner in which people gauge facial attractiveness. It also may have the capacity to unearth disparities in aesthetic preferences across diverse cultural contexts by scrutinizing interactions among users from different geographic regions and ethnic backgrounds. Recent studies have embarked upon the utilization of machine learning techniques to delve into the aesthetics of facial images69,70 Iyer et al employed a dataset comprising 5500 facial images, which were evaluated by a panel of 60 volunteers and rated for beauty on a 5-point Likert scale.69 This dataset was then employed to train a model capable of tasks including landmark localization, extraction of facial feature sets, and evaluation of an array of predetermined ratios. Iyer et al’s analysis indicated that facial images deemed aesthetically pleasing exhibited correspondence with the principles of neoclassical facial proportions. However, their study predominantly concentrated on evaluating the ratios of crucial facial landmarks. This underscores the need for more sophisticated algorithms capable of comprehensively appraising the subtler intricacies inherent within facial features.

Limitations

Numerous limitations within this review warrant acknowledgment, foremost among them being the challenge of comparing studies due to the diversity in units employed to define aesthetic ideals. Secondly, a lack of standardized measurement for attractiveness is noteworthy. The prevailing method involves plastic surgeons assessing faces/units on a Likert scale; yet discrepancies arise as certain studies solely incorporate laypersons as reviewers, while others opt for a combination. In an optimal scenario, a balanced review panel is advocated, alongside the presentation of rater demographics. Reviewers’ distinctions rooted in ethnicity, gender, and age manifest distinctly, evident notably in the periorbital area, with studies emphasizing different East Asian and Caucasian ideals. Hence, it becomes imperative for studies to elucidate their focal ideals and for surgeons to acknowledge cross-cultural aesthetic variations. Furthermore, the bulk of studies within this review centered on Caucasian females, underscoring the need to discern the patient demographic to which the findings of the included papers predominantly apply. Another important limitation in establishing aesthetic ideals for facial units lies in their evolutionary nature. An illustrative instance is the Westmore brow, emblematic of the 1970s and characterized by a slender, high-arched, and medially peaked brow21—a contrast to contemporary inclinations favoring thicker brows with lateral peaks. This dynamic shift underscores how these ideals evolve over time.

An additional crucial aspect of this study pertains to the predominant focus of the included papers on delineating optimal parameters for specific female facial anatomic units, rather than encompassing a compressive definition of beauty. Recognizing beauty involves intricate interplays of numerous elements extending beyond mere measurements and proportions—an intricacy exceeding the scope of this paper.

CONCLUSIONS

This review has examined the current evidence regarding the aesthetic ideals of the face. Our findings indicate that although there are numerous definitions available for the aesthetic ideals of various facial subunits, many measurements have not been empirically defined or consistently validated. Farkas's work made progress in quantifying facial dimension measurements by categorizing and documenting numerous measurements for each facial unit, although these have not been utilized to establish aesthetic ideals. With the advancements in computer modeling and automation, we now have the capability to take a significantly greater number of facial measurements, aiding in the assessment of aesthetic ideals. Furthermore, we have emphasized the significant gaps in aesthetic classifications for certain facial units, such as the ear and chin. We have summarized key papers that we believe will be valuable for aesthetic surgeons. Going forward, it is imperative to conduct more standardized studies that explore and define aesthetic ideals in a comprehensive manner.

Supplemental Material

This article contains supplemental material located online at www.aestheticsurgeryjournal.com.

Disclosures

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Mr Faderani and Mr Singh are plastic surgery trainees and Prof Mosahebi is a professor of plastic surgery, Division of Surgery & Interventional Science, University College London, London, UK.

Dr Monks is a general practitioner, Dr Dhar is an aesthetic practitioner, and Mr Ponniah is a plastic surgeon, Department of Plastic Surgery, Royal Free Hospital, London, UK.

Prof Krumhuber is a professor of psychology, Department of Experimental Psychology, University College London, London, UK.