-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Miguel Gonçalves Ferreira, Dean M Toriumi, Bart Stubenitsky, Aaron M Kosins, Advanced Preservation Rhinoplasty in the Era of Osteoplasty and Chondroplasty: How Have We Moved Beyond the Cottle Technique?, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 43, Issue 12, December 2023, Pages 1441–1453, https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjad194

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Over the last 10 years, many new papers on innovative strategies from different surgeons worldwide have elevated the philosophy of preservation rhinoplasty (PR) to a different level: advanced preservation rhinoplasty.

The goal of this article was to illustrate how 4 experienced surgeons approach important anatomical and functional issues related to PR.

M.G.F., A.M.K., B.S., and D.M.T. were asked about how they approach classical problems and relative contraindications for dorsal PR with different modern advanced preservation rhinoplasty techniques.

The answers of each surgeon make clear a new reality in dorsal PR that did not exist in the recent past. These advances in dorsal PR techniques are due to many surgeons’ contributions, leading this practice to a different level: advanced preservation rhinoplasty.

Dorsal preservation is making a dramatic resurgence and is fueled by the many very talented surgeons who are demonstrating outstanding outcomes with preservation techniques. The authors believe that this trend will continue, and a mutual collaboration between structuralists and preservationists going forward will continue to advance rhinoplasty as a specialty.

See the Commentary on this article here.

In 1899, Goodale introduced dorsal preservation (DP), and this was followed by Lothrop in 1914 and Cottle in 1946.1-3 Moving forward from the 1950s, a select group of innovative surgeons performed and improved DP in a surgical world dominated by reduction techniques. The concept of preserving the good features of the dorsum and the middle vault is theoretically superior to reduction. This strategy may have been universally accepted if not for some issues of surgical imprecision, loss of control, and structural unpredictability. These factors, along with the advent of the open approach, influenced surgeons to turn to structure rhinoplasty (SR), because it presented more precise and predictable results. Despite all the subsequent improvements of middle vault reconstruction, with new grafts and flaps developed by eminent worldwide surgeons, the “preservers” continued to believe that preservation rhinoplasty (PR) could achieve better dorsal outcomes in a select group of patients.

In the past decade, new concepts of nasal anatomy have emerged due to cadaver studies and, more recently, accurate radiological studies.4,5 These ideas and findings have allowed new modifications of the early push-down/let-down techniques. Daniel recently coined the descriptive title “preservation rhinoplasty” (PR), and it has become a rather popular movement in recent years.6

PR is rapidly gaining popularity among surgeons. Due to the expansion of techniques and a new understanding of anatomy, we are now in the era of advanced preservation rhinoplasty (APR). Patients who in the Cottle era were not considered ideal candidates for DP may now be suitable. The main objective of this article is to provide an overview of surgical solutions to common problems and unique perspectives that allow expansion of the indications for DP. To achieve this, 4 renowned surgeons with experience in APR provided answers regarding how they expand the use of DP techniques in their own practices. As described herein, the concepts of osteoplasty and chondroplasty in rhinoplasty have changed the paradigm and broadened the indications for PR.

METHODS

Eleven questions regarding new aspects in advanced DP were answered, individually and independently, by 4 experienced surgeons: M.G.F., A.M.K., B.S., and D.M.T. The answers were limited to 100 to 150 words each.

RESULTS: QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS

How Do You Manage the Medium/Severe S-Shaped Nasal Bones?

M.G.F.

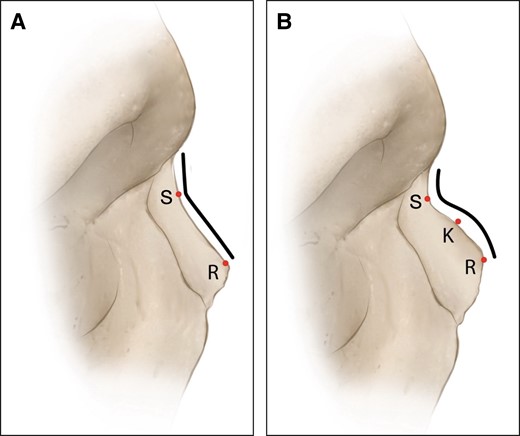

Big humps are more likely to have a bony kyphosis. The S-shaped nasal bones (Figure 1) will impact surface anatomy and must be diagnosed before surgery, if possible, with a computed tomography scan. If the kyphosis is significant, one must perform ostectomy or osteoplasty—in this case, I uncap the hump as far as needed with a diamond drill (preferable) or piezoelectric (PEI) system. I dissect the bony dorsal compartment. I use a superficial preservation approach to dehump a nose with S-shaped nasal bones: spare roof technique A.7-9

(A, B) V- and S-shaped nasal bones. K, kyphosis; R, rhinion; S, sellion.

A.M.K.

Although moderate S-shaped humps can be managed with bony cap modification and DP, severe S-shaped nasal bones are managed with SR. When the nasal bones have a very high kyphion point, the bone must be excessively modified or removed, and the underlying cartilaginous vault becomes exposed. The cartilage vault under the nasal bones is often denuded of perichondrium and has irregularities on the dorsum where the skin is the thinnest. Although these dorsums can be treated with DP, SR is easier, and the outcomes are more consistent. In addition, patients with severe S-shaped nasal bones often have a low radix and/or a low anterior septal angle. These anatomic characteristics make flattening maneuvers even more difficult.

B.S.

S-shaped nasal bones are a relative contraindication for preservation of the bony vault. In slightly S-shaped nasal bones, I try to change the S-shape to a V-shape by rasping. If successful, I proceed with a let-down or push-down as usual. In severe S-shaped nasal bones, I revert to structural techniques for the bone. This can be done by extensive rasping or removal of the bony cap followed by osteotomies.

D.M.T.

My method of management of the severe S-shaped nasal bones depends on the status of the radix. The S-shaped dorsal hump has an S-shaped angulation from the nasion to rhinion, whereas the V-shaped hump has a straight-line configuration from nasion to rhinion. If the radix is low and requires augmentation, I place a radix graft to a level that is appropriate for the patient. Elevation of the radix will decrease the prominence of the S-shaped deformity. Then the remaining hump can be managed with the PEI or a rasp to take down the bony cap. Once the bony cap is reduced, the cartilaginous dorsum can be reduced with an intermediate level flap such as the subdorsal Z-flap or Tetris.10 I take out bilateral bone strips (let-down) through subperiosteal tunnels, bilateral transverse bone cuts through small stab incisions, and the radix osteotomy from below. If the radix is not low and does not require augmentation, I utilize the spare roof type B technique of Ferreira and Ishida and use a PEI to take out triangular segments bilaterally to allow the projecting component of the S-shaped hump to be collapsed on itself and sutured into a flattened position.11 This will convert the S-shaped hump to a straight profile line. Even in these cases, I may use a small, crushed cartilage radix graft. I prefer to place radix grafts into a narrow subperiosteal tunnel and then fix them into place with a 6-0 Monocryl (Ethicon, Raritan, NJ) transcutaneous fixation suture.

How Do You Manage the Low Radix?

M.G.F.

A low radix is a very important entity in nasal aesthetics. Due to long-term issues with visibility, I usually avoid putting grafts in the radix area. When the deepness is relevant, I use diced cartilage in a subperiosteal tunnel that I create specifically for this purpose. In extreme cases, I still utilize the “diced cartilage in fascia” proposed by Daniel et al.12

A.M.K.

The low radix is a relative contraindication for an impaction technique. Even if a hinge is created at the radix, some amount of radix lowering often occurs. Most often, a surface technique is performed in which the bony cap and cartilaginous vault are lowered with high septal strip removal. This has been the most consistent and reliable way to manage the low radix, in addition to radix grafts of diced cartilage in fascia. An open technique is more often employed for surface techniques because of the large exposure and ability to sculpt the bones with PEI.

B.S.

A low radix can be a presurgical finding or an iatrogenic result of the surgery when using bony vault lowering techniques. In both cases, I solve the issue by augmenting the depressed area with minced cartilage. A narrow subperiosteal tunnel (4-mm wide) is made cranially beyond the deepest point without dissection of lateral walls. The minced cartilage is then applied with an applicator syringe.

D.M.T.

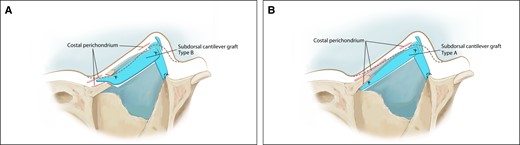

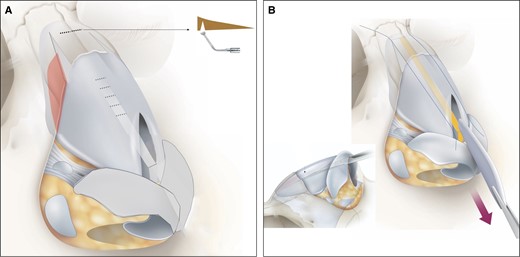

I manage the low radix with a radix graft placed into a narrow subperiosteal pocket and then fixated with a transcutaneous 6-0 Monocryl suture that is removed on the seventh postoperative day when the cast is removed. I can also place the radix graft through the lateral wall stab incisions. If the dorsum and radix are low and both require augmentation, I use a push-up technique incorporating a subdorsal cantilever graft (SDCG) type B (Figure 2A).13,14 This graft is carved from autologous costal cartilage and is specifically designed for the patient's needs. After performing bilateral lateral osteotomies, bilateral transverse osteotomies, and a radix osteotomy, the SDCG type B is extended through the radix osteotomy to raise the entire dorsum, including the radix. Complete release of the lateral keystone and piriform ligament is also required to allow the middle vault to be pushed up. The SDCG type B is then fixed to a caudal septal extension graft to create a new L-shaped support structure.

How Do You Manage the Supratip Area?

M.G.F.

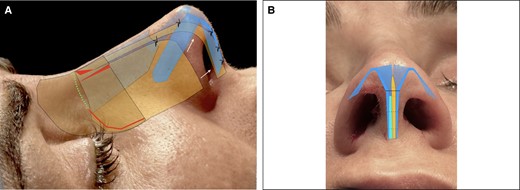

In PR, the supratip area is critical whether one performs high, low, or intermediate strip strategies. Recently I`ve introduced the septal advancement flap (SAF) in all primary cases (Figure 3), so I have a smooth continuity between W-point, tip, and upper lip.15 With the SAF, it is critical to double-check that the “supratip suture” is in the correct position to have a stable relationship in the complex septum/lower lateral cartilages/domal area.

(A, B) Septal advancement flap applied to the spare roof technique in a 44-year-old female patient.

A.M.K.

The supratip area is managed last in a high strip technique, whether with a surface or impaction technique, by preserving the W-ASA segment (the W point is the caudal point of separation of the upper lateral cartilages from the septum, and the ASA point is the anterior septal angle). If the supratip is low preoperatively, this is a relative contraindication for DP, and a low strip technique should only be employed if the caudal septum is strong and if the surgeon can rely on the flap to rotate and push up the anterior septal angle. If a strong supratip break point is present preoperatively, structural dorsal rhinoplasty should be considered to retain complete control of the dorsal profile.

B.S.

Often, this issue can be anticipated by preoperative examination when palpating a downward curvature of the dorsum caudally. There are several options to correct a supratip depression, depending on the severity. If there is a slight depression, the issue can be solved by either the placement of a thin cartilage graft (ideally a thin cephalic trim graft) or releasing the caudal upper lateral cartilages and suturing them together above the septum. A second, more caudal vertical cut can be made in more severe cases. This creates 2 QC flaps with 2 pivot points, enabling the elevation of the supratip area.

D.M.T.

The supratip area is managed based on the desired position after the tip projection is set. If the supratip requires lowering, such as in a tension nose deformity, I use a Tetris flap with the vertical incision of the caudal segment of the flap extending through the W point.16 This will allow precise control of the supratip position by advancing or lowering the connection of the Tetris flap to the caudal strut. If the supratip is in proper position, I use a subdorsal Z-flap, without extending the caudal cut through the W-point to preserve the supratip position.17,18 If the supratip is too low, I place a small soft tissue onlay graft into the depressed area. If a saddle nose deformity is noted, I raise the saddled area with an SDCG type A that elevates the supratip/saddle and is fixed to a caudal septal extension graft (Figure 2B).13

How Do You Manage the Upper Lateral Cartilage (ULC) Shoulders?

M.G.F.

ULC shoulders might be a problem in surface anatomy if they are prominent, asymmetric, or both. In these cases, I dissect only the dorsum's cartilaginous segment and use a Colorado needle (Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI) to burn the shoulders (chondroplasty). I utilize it with the lowest potency that is efficient. The concept of chondroplasty has emerged with the use of electromedicine—Colorado tip, laser, etc. After doing so, I do interpose some kind of absorbable material (Spongostan; Johnson & Johnson Medtech, New Brunswick, NJ) between the roof and the envelope to avoid any kind of skin fibrosis or retraction during the first healing period.

A.M.K.

If the ULC shoulders are prominent or asymmetric, they are best treated by shaving with a blade or electrocautery. At times a lateral keystone release can help to treat these asymmetries, but after the dorsal preservation has been completed, the ULC shoulders can be modified to smooth the profile. Surgeons will find that the left ULC shoulder often sits higher than the right, and this can easily be modified.

B.S.

This challenge often justifies structural rhinoplasty techniques. If, like me, you want to use preservation, there are a couple of solutions. For broad ULC shoulders, I partially incise the cartilage of the dorsum on the new desired dorsal lines. This takes off the tension and narrows the ULCs. If the shoulders are sharp or elevated, careful sculpting of the edges can be performed with electrocautery to soften them. Finally, if there is serious bulging or broadness of the ULCs, the release of the ULCs from the septal T with trimming of the excess is an efficient solution.

D.M.T.

I manage the ULC shoulders by trimming with a 15 blade, preserving the underlying mucosal lining. The lining preserves support and prevents deformity. To create the proper contour, I may place a 6-0 Monocryl suture to close the small cartilaginous defect. Another option is to employ gentle electrocautery (Colorado needle) to sculpt the high upper lateral cartilage shoulder.

How Do You Manage the Crooked Nose?

M.G.F.

In PR, the crooked nose is always managed with the following rational basis: tension on the cartilaginous middle vault is solved with the releasing of the septum at any level (high, intermediate, or low). Structurally the final result will be similar because the remaining attached septum will be tilted to the contralateral side of the deviation with high and medium strip (side to side), or will be tilted to the same side in low strip in a swinging door fashion. The crooked nose is managed with my standard surface technique—spare roof technique B.19 Once the roof is released from the septum (high strip), the nose tends to immediately become straight, and the septum remains crooked. For nonsevere septal deviations, I perform a regular L-shape septoplasty and suture the upper part asymmetrically to the roof. If the septal deviation is severe, I do an extracorporeal septoplasty (preserving the roof).

A.M.K.

If the crooked nose is secondary to axis deviation, the best way to manage the nose is with an asymmetric, let-down technique (impaction). Moderate deviations are addressed with a subdorsal Z-flap technique (Figure 4), in which the flap is locked to the contralateral side of the septal deviation, and a septoplasty is performed separately to release the tension. For severe deviations, a low strip technique is used to move the entire osseocartilaginous vault and septum as 1 flap. If the patient has intracorporeal damage or distortion (usually from trauma), often a subtotal septoplasty is necessary.

B.S.

By far, the most efficient technique for managing crooked noses in PR is a cartilaginous low strip combined with an asymmetric bony vault let-down, or SPQR (Figures 5, 6). The septum's vertical release from the ethmoid's perpendicular plate swings the septum tensionless into the midline. The complete release of the bony vault then lets it follow the cartilaginous vault.

D.M.T.

I manage the deviated nose with axis deviation based on the status of the nasal septum. If the nasal septum is not severely deviated in absence of a high septal deviation at the ethmoid bone, I release the bones and middle vault from the septum with an intermediate level flap (subdorsal Z-flap, Tetris, or Ishida) and then perform bilateral bone strips (let-down), taking out a larger strip on the side opposite the deviation. I also perform bilateral transverse bone cuts and a radix bone cut from below. Then the intermediate level flap is overlapped on the side opposite the deviation to shift the dorsum to the midline. If the nasal septum is severely deviated and/or if there is a high septal deviation involving the ethmoid bone, I employ a low strip (SPQR, Cottle, SPAR [septum pyramidal adjustment and repositioning] type B) by releasing the entire septum from the bony attachments.20-22 This allows the overly large quadrangular cartilage flap to be trimmed and rotated caudally and then fixed to the nasal spine. In the absence of a dorsal hump, a septal flap is created, and minimal rotation avoids dropping the dorsum. This is a type of swinging door septal flap. The deviated ethmoid bone can be removed to allow straightening of the bony septum. Care must be taken to create an angled oblique radix bone cut leaving the external periosteum attached to the bone to avoid dropping the radix. I prefer a “no dorsal skin elevation” method to preserve nasal bone integrity and support. In most cases, I utilize osteotomes and a rongeur for the bone cuts with no dorsal skin elevation over the dorsum. For the severely deviated nose with an S-shaped deformity, I use structure methods. If there is deviation and saddling of the middle vault, I employ a subdorsal cantilever graft type A to straighten the dorsum and raise the middle vault.

I do not believe the low strip (Cottle, SPQR, SPAR type B) has fallen out of favor. To the contrary, I believe improvements made in the technique (SPQR) have increased the utility of the low strip.23 The technique demonstrates superior benefit for the deviated nose and deviated septum with high septal deviation.

How Do You Prevent the Hump Recurrence and Manage the Lateral Keystone Area (LKA)?

M.G.F.

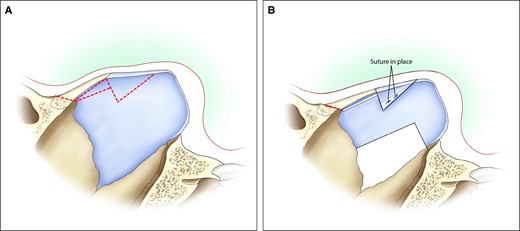

Probably the most important structural movement in DP is the release of the LKA. The 3-dimensional (3D) structural architecture of the cartilaginous middle vault is very important to understanding how safe it is to release the LKA in DP. Once the integrity of the middle vault is maintained, one can release the LKA, and the 3D architecture will be the same. Splitting the bony and cartilaginous part of the middle vault in the lateral wall is the key to pushing the roof down and flattening the dorsum. In big humps or severe S-shaped nasal bones the roof should be sutured to the septum as described by Ferreira (Figure 7).11

Spare roof technique B. (A) Lateral wall and subdorsal ostectomy. (B) High strip and central compartment.

A.M.K.

When utilizing a surface technique, a high strip is almost always done. Hump recurrence is prevented with a 3-suture fixation technique as previously described. With an impaction technique, the surgeon must check all possible blocking points, including Webster's triangle, bony contact at the lateral osteotomy lines, internal periosteal dissection at the lateral osteotomy lines, lateral keystone release, and full bony mobilization. For a high strip impaction, the surgeon must also check to make sure that the subdorsal keel has been removed. For a low strip impaction, the surgeon must make sure the osseocartilaginous joint is completely released and that the posterior septal angle of the caudal septum rests on the anterior nasal spine without tension (which can cause the flap to migrate cephalically postoperatively) and without excessive caudal septal length (which can deviate the nose postoperatively).

B.S.

The most frustrating complication in PR is hump recurrence. It is caused by an insufficient release of blocking points and inadequate fixation of the cartilaginous vault. Blocking points can be bony (under the bony cap, at the middle keystone area [MKA], or at osteotomy sites) or cartilaginous (LKA or septum underneath pivot point). By removing sufficient bone under the vault, rasping the MKA, banana-shaped ostectomies, and by releasing the LKA (ballerina move) and incising the septum under the pivot point, recurrence can be prevented.

Good fixation of the cartilaginous vault by 2 sutures in the high strip and reliable fixation of the septum to the anterior nasal spine is essential to keeping the dorsum in place.

D.M.T.

I prevent hump recurrence by managing all the potential blocking points and with suture fixation methods. I perform a lateral keystone release for larger dorsal humps and more severely deviated noses. I release the LKA and piriform ligament on the side opposite the deviation in the deviated nose. I do a banana-shaped lateral bone strip removal to make sure there is no blocking point near the medial canthal ligament. I make sure I take out a generous bone or cartilage segment below the bony hump. I also release the periosteum around the lateral bone strip removal to prevent a blocking point at the maxilla. I check the subdorsal area at the rhinion to make sure there is no residual cartilage spanning the bone cartilage junction. Vertical cuts can be made through any remnant cartilage below the rhinion to allow flexing of the K-area to “stretch and flatten the hump.” I place a fixation suture (4-0 PDS) to fixate the dorsum into the reduced position on the septal flap (subdorsal Z-flap, Tetris, etc.) and/or a transmucosal suture through the middle vault and septum.

How Do You Manage Bony Dorsal Irregularities?

M.G.F.

Bony dorsal irregularities have to be diagnosed before surgery because they change the strategy. Once irregularities have an impact on surface anatomy, I have to dissect the dorsum (which I do not do routinely), and typically they are fixed before any maneuver, by ostectomy/osteoplasty with a diamond burr or (if not possible) with PEI. Care must be taken to avoid any soft tissue envelope or skin injuries. The most frequent “irregularity” is kyphosis of the S-shaped nasal bones.

A.M.K.

All bony dorsal irregularities are managed with piezoelectric rhinosculpture. This can be done before or after DP, and the bones can be modified as you proceed throughout the operative sequence. The use of rasps and osteotomes is often too aggressive and causes radiating fracture lines, loss of the bony cap, and irregularities, especially if the dorsal preservation has been completed and further modification is necessary.

B.S.

Rasping is the easiest and most effective solution for bony vault irregularities. Let-down or push-down can be performed following reshaping into the desired form.

D.M.T.

Intraoperatively, I manage dorsal irregularities with a piezotome, narrow rasp, or trimming of the cartilage. If I note an irregularity postoperatively, I correct it with a narrow rasp if it is bony. If it is cartilage, I may consider an in-office “needle shave,” in which I place local anesthetic over the area and with a 16-gauge needle shave down the cartilage deformity.24 I do not use filler in the nose.

How Do You Manage ULC Irregularities and Asymmetries?

M.G.F.

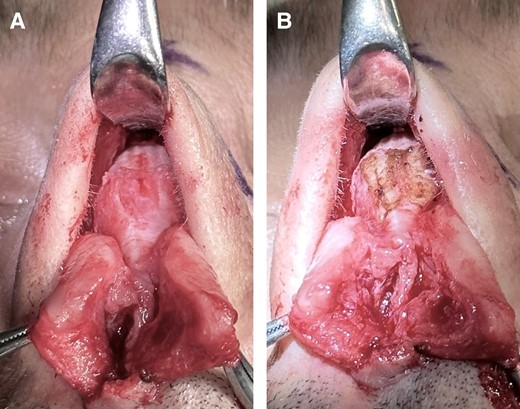

As with bony irregularities, cartilage asymmetries or irregularities must be diagnosed before surgery, and the dorsum is dissected in that specific area. Asymmetries are frequent in the crooked nose and are solved with bilateral dissection of the LKA (excess of ULCs sink in the dissected LKA). Irregularities, including ULC shoulders, are typically treated with Colorado tip cautery in vaporization mode at the lowest potency possible. After doing so, one should interpose some material (Spongostan) in between the burned area and the soft tissue envelope (Figure 8).

Chondroplasty with electrocautery (Colorado needle) of the upper lateral cartilage shoulders in a 38-year-old male patient.

A.M.K.

See previous response. For severe concavities, I often add submucosal spreader grafts in predissected pockets. This is very common in axis deviation, in which a submucosal spreader is added opposite the side of the deviation. Small onlay lateral wall grafts are placed caudally as necessary.

B.S.

For cartilaginous vault irregularities or asymmetries, structural rhinoplasty techniques are justified and probably easiest. For preservation, the irregularities or asymmetries can be carefully sculpted with electrocautery or a blade. But again, the threshold to convert to structural should be low.

D.M.T.

ULC asymmetries or irregularities can be managed with a shave of the prominent shoulder. If the upper lateral cartilages are asymmetric and 1 side is too narrow or medialized, I place a submucosal spreader graft, in which the rectangular-shaped graft is placed into a narrow subperichondrial pocket (Figure 9).18,24 This lateralizes the medialized upper lateral cartilage. If the middle vault is too wide, I perform bilateral segmental spreader flaps. In this case, the upper lateral cartilages are freed from the dorsal septum, and then spreader flaps are created and sutured with a 5-0 PDS suture to set a narrower middle vault. This is not a preservation technique.

Unilateral spreader graft to correct upper lateral cartilage asymmetries.

How Do You Manage Dorsal Aesthetic Lines (DALs)?

M.G.F.

DALs are the most important aspect of spare roof technique B. The triangular ostectomy is always done immediately in the exterior aspect of the desired DALs. After this maneuver, the traditional lateral osteotomies are done in a greenstick fashion, closing the “greenstick ring” of this technique—the barn doors greenstick fracture.25 The cartilaginous part of the DALs is treated, when needed, with Colorado tip cautery, as mentioned previously.

A.M.K.

When doing dorsal preservation, it is optimal to have excellent dorsal aesthetic lines, and an impaction technique can be employed without skin dissection. However, most dorsums require modification. If an impaction technique is employed, the bony dorsum is sculpted to achieve optimal DALs before impaction. Maximum modification can be done with a surface technique, in which the surgeon can combine bony modification and sequential piezoelectric osteotomies for maximum control of the bony vault.

B.S.

If the dorsal aesthetic lines are good preoperatively, they will look even better after use of a low septal strip. With a high septal strip broadness might occur, with extensive lowering or shortening. For this unwanted effect, there are a couple of solutions. If the dorsum is too broad, the cartilage of the dorsum can be partially incised on the new desired dorsal lines. This takes off the tension and narrows the ULC. Finally, if there is serious bulging or broadness of the ULC, release of the ULC from the septal T with trimming of the excess is an efficient solution.

D.M.T.

I manage the dorsal aesthetic lines by preserving them when they are favorable. This is the major upside of the dorsal preservation techniques. If the dorsal aesthetic lines are unfavorable, I use surface modification techniques to reset the DALs. If the bones are asymmetric or too wide, I perform a wide subperiosteal dissection and use PEI to sculpt the bones to a proper width and contour. If the middle vault is too wide, I utilize segmental spreader flaps as previously described. If there are small depressions at the end of the case, I place small soft tissue grafts into the depressions and fixate the grafts transcutaneously with a 6-0 Monocryl suture. If the DALs are too wide or asymmetric in the augmentation rhinoplasty patient or secondary rhinoplasty patient, I use a narrow asymmetrically carved subdorsal cantilever graft to contour the DALs into a straight and symmetric contour.

How Do You Manage Big Humps (>5 mm)?

M.G.F.

Big humps are always a problem per se; most of the time, they are part of a “big nose.” The outcomes might be suboptimal with traditional maneuvers, even with a structured approach. In these cases, and with PR, the possible spring effect tends to be bigger, and the final position of the roof is less predictable. The technique is the same but with 2 extra measures: be sure to complete LKA dissection and suture the roof to the remaining septum (only after feeling no resistance)—the “hump apex suture,” with 1 or 2 sutures.

A.M.K.

With humps bigger than 5 mm, surface techniques are not employed. The lateral keystone release is extensive with complete or near complete disarticulation of the bones from the cartilaginous vault. Large humps are treated with impaction techniques or SR.

B.S.

For me, the most eloquent technique to manage big humps is a cartilaginous low strip combined with a bony vault let-down (SPQR). With a low strip, one not only lowers but also lengthens the midvault, enabling significant descent of the dorsum without it looking unnatural or broad.

D.M.T.

For larger dorsal humps, I utilize a Tetris or low strip to allow maximal subdorsal control and stability. If there is an S-shaped component to the hump, I take down the bony cap with a rasp or piezotome or use a spare roof type B with a radix graft (if the radix is low). With bigger dorsal humps, managing the potential blocking points is critical to preventing hump recurrence (LKA release, banana osteotomy, subdorsal cartilage/bone removal, periosteal elevation, etc.). I place 1 or 2 transmucosal sutures to help fix the hump in a reduced position. In larger humps, I also place lateral bone sutures that go through holes in the bones along the ascending process of the maxilla to hold the hump down. Another key is to make sure one has excellent stable tip projection and radix position to help camouflage a residual dorsal convexity. In most cases, I employ structure techniques in the tip such as a caudal septal extension graft to maximize tip support and preserve tip projection.24 This concept is very helpful with larger dorsal humps.

In Primaries, What Are Currently Your Main Contraindications for Dorsal Preservation Rhinoplasty?

M.G.F.

The spare roof technique, like most surface techniques, has no absolute contraindications in primary rhinoplasties. Grossly I apply this technique in all primary rhinoplasties. Exceptionally, extremely difficult primaries demand exceptional adjuvant maneuvers—less than 2% of all primaries, such as severe deformities due to closed trauma and/or severe asymmetric dysmorphias, demand some hybrid procedures in the dorsum or at maximum, a classical structured strategy.

A.M.K.

The main contraindications for DP are severe S-shaped nasal bones, a low radix combined with a low supratip region, severe middle vault asymmetries, complex septal deviations, a preoperative appearance of an inverted V, and any patient for whom I think a structural surgery will be easier and faster to get the same result.

B.S.

I try to do all my primary rhinoplasties with preservation techniques. In 85% I do complete preservation of the dorsum (cartilaginous and bony) and the tip. In the remaining primaries, I use a hybrid approach depending on the anatomy of the nose. Relative contraindications to preservation rhinoplasty are:

bony vault: S-shaped dorsum, extremely broad dorsum

cartilaginous vault: severe broadness

Tip: I use a septal extension graft if the tip has very thick skin, if the tip cartilages are very weak, if the desired up rotation of the tip is significant, or if I employ a high strip.

D.M.T.

My indications for dorsal preservation in primaries are very liberal. I use dorsal preservation in greater than 90% of primary rhinoplasties. I utilize dorsal preservation in patients with dorsal humps, deviations, and low dorsums requiring augmentation. I employ structure in primary cases where there are complex bone or middle vault deformities that require structural grafting for complete correction. In the wide nose, I use a hybrid approach, employing rhinosculpture for narrowing the wide nasal bones and segmental spreader flaps for the wide middle vault. I believe dorsal preservation rhinoplasty is contraindicated in cases in which the septum has been previously resected, leaving less than 15 mm of dorsal strut, and cases in which there is disruption of the keystone in the midline due to previous trauma, surgery, or iatrogenic disruption.

When Do You Perform Dorsal Non-Dissection?

M.G.F.

Dorsal non-dissection was first described by Goodale in 1899 in “a new method for the operative correction of exaggerated roman nose”; later it was popularized by Maurel (1940), Gola, and Saban, among others.1 The dorsal non-dissection is a common step of the spare roof technique B, with exceptions: medium/big bony kyphosis, ULC shoulders or other middle vault irregularities with impact on surface anatomy, big reductions in which redraping of the skin is necessary. The subdorsal osteotomy (radix greenstick fracture) allows complete dorsal preservation without any dissection or perforation of the skin in selected patients.

A.M.K.

When doing dorsal preservation, only with impaction techniques do I not dissect the skin. I do no dorsal skin dissection when the patient has V-shaped nasal bones that do not require any bony modification or rhinosculpture. Osteotomies are performed internally for the low osteotomies and through small stab incisions with ice cold water and a small piezoelectric saw through the transverse nasal incision. The healing is very rapid and the surgeon does not need to worry about damage to the soft tissue envelope (Figure 10).

Utilizing the piezoelectric device through the skin of a 35-year-old female patient.

B.S.

Over the years I have moved toward minimal dorsal skin dissection. In the majority of cases (>95%) the scroll ligament is not opened. Through the hemitransfixion incision, a narrow (3-4 mm) midline tunnel over the dorsum is made, starting at the caudal septal border, extending to the K-area or the sellion if needed. Through this tunnel I then can:

resect the caudal border of the ULC if shortening the nose by an up rotation of the tip

rasp the K-area to weaken the hinge or transform an S-shape into a V-shape

perform the ballerina maneuver (release of LKA) to facilitate flattening of the hump

add a graft to the sellion or K-area (minced cartilage or bone dust)

Lateral banana-shaped osteotomies are performed through an internal incision on the piriform rim; transverse and radix osteotomies (1-2 mm) are done transcutaneously, eliminating the need for lateral dorsal skin dissection. In cases in which the dorsum is straight and just has to be lowered, no skin dissection at all is done.

D.M.T.

I try to use a “no dorsal skin elevation” approach in all primary rhinoplasties with a V-shaped dorsal hump that do not require rhinosculpture or modifications of the upper lateral cartilages (upper lateral cartilage shoulders, etc.). In these cases, I dissect up to the W-point and leave the dorsal nasal skin intact and undissected. I perform the radix osteotomy from below, the transverse bone cuts through small lateral wall stab incisions, and removal of lateral bone strips through subperiosteal tunnels. The no dorsal skin elevation techniques provide rapid healing and excellent short-term and long-term outcomes. I also frequently employ no dorsal skin elevation techniques when I use a subdorsal cantilever graft to raise the dorsum of the nose.

In Primary Rhinoplasty, What Is Your Percentage of Dorsal Preservation Rhinoplasty?

M.G.F.

>98%.

A.M.K.

70%.

B.S.

85% to 98% (sometimes hybrid).

D.M.T.

>90%.

DISCUSSION

During the last 5 to 10 years, PR has evolved into the current era of advanced preservation rhinoplasty. The vast majority of the problems with traditional PR have been solved due to the persistence of well-known and talented surgeons, turning this practice into a comprehensive set of solutions and strategies that are much more accurate and predictable.7,10,26-35

In addition, the “marriage” between 2 iconic and seemingly opposite philosophies—structure and preservation—has become synergistic, improving and merging the best solutions, and now many surgeons use structural preservation rhinoplasty (SPR).18 Whether a surgeon employs structural techniques, preservation techniques, or a fusion of both depends on the surgeon's comfort as well as their patient population.

A main theme throughout this question and answer session was that the possibility of changing the bone and cartilage shape has expanded the indications for DP. The new concepts of osteoplasty (PEI or burr) and chondroplasty (Colorado needle, laser, or permanent sutures) have entered the era of advanced preservation rhinoplasty.

CONCLUSIONS

Dorsal preservation is making a dramatic resurgence and is fueled by the many talented surgeons who are demonstrating outstanding results with preservation techniques. This group of surgeons has, in many ways, lead the revival and inspires many.7,10,26-35 We are strong believers that this trend will continue, and that a mutual collaboration between structuralists and preservationists going forward will continue to advance rhinoplasty as a specialty.

Disclosures

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Dr Ferreira is an otolaryngologist, Nose and Face Clinic, Santo António University Hospital Center, University of Porto, Hospital da Luz–Arrábida, Porto, Portugal.

Dr Toriumi is a facial plastic surgeon in private practice in Chicago, IL and is a clinical editor for Aesthetic Surgery Journal.

Dr Stubenitsky is a plastic surgeon in private practice in Amsterdam, the Netherlands and is a Rhinoplasty section editor for Aesthetic Surgery Journal.

Dr Kosins is an assistant clinical professor, Department of Plastic Surgery, University of California, Irvine School of Medicine, Irvine, CA and is a Rhinoplasty section editor for Aesthetic Surgery Journal.