-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Rachel M Smith, Srishti Rathore, D’Andrea Donnelly, Peter J Nicksic, Samuel O Poore, Aaron M Dingle, Diversity Drives Innovation: The Impact of Female-Driven Publications, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 42, Issue 12, December 2022, Pages 1470–1481, https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjac137

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Gender disparities are pervasive in academic plastic surgery. Previous research demonstrates articles authored by women receive fewer citations than those written by men, suggesting the presence of implicit gender bias.

The aim of this study was to describe current citation trends in plastic surgery literature and assess gender bias. The expectation was that women would be cited less frequently than their male peers.

Articles published between 2017 and 2019 were collected from 8 representative plastic surgery journals stratified by impact factor. Names of primary and senior authors of the 50 most cited articles per year per journal were collected and author gender was determined via online database and internet search. The median numbers of citations by primary and senior author gender were compared by Kruskal-Wallis test.

Among 1167 articles, women wrote 27.3% as primary author and 18% as senior author. Women-authored articles were cited as often as those authored by men (P > 0.05) across all journal tiers. Articles with a female primary and male senior author had significantly more citations than articles with a male primary author (P = 0.038).

No implicit gender bias was identified in citation trends, a finding unique to plastic surgery. Women primary authors are cited more often than male primary authors despite women comprising a small fraction of authorship overall. Additionally, variegated authorship pairings outperformed homogeneous ones. Therefore, increasing gender diversity within plastic surgery academia remains critical.

See the Commentary on this article here.

Gender disparity in the field of plastic surgery and academic medicine is a persistent problem. Existing research demonstrates that academic plastic surgeons tend to be males, and that females experience significant promotion and leadership inequalities as, when controlling for experience, they are less likely to be full professors than their male collegues.1,2 Profound differences are also reported in the number of articles published by women at the assistant and full professor level.3 Women are less likely to be presenters and senior authors at national plastic surgery meetings where academic work has the potential to be broadly disseminated to the scientific community.4 Despite women consistently contributing to 50% or more of the incoming medical school classes, the number of plastic surgery trainees identifying as female has remained around 40% since 2014; in 2019, based on integrated plastic surgery program websites, the female-to-male trainee ratio was 0.86.5-7 Although the female-to-male proportion of plastic surgery faculty has increased from 1:9.2 to 1:5.3 between 2008 and 2013, women remain underrepresented along the academic ladder.8,9

This is known as the “leaky pipeline” phenomenon, which may be explained by the multitude of barriers women face when working in academic medicine as a result of implicit gender bias—unconscious assumptions about males and females formed as a result of “cultural and societal expectations, learned behaviors, and standardized associations.” 10-12 These include, but are not limited to, sexism, imposter syndrome, lack of female mentorship in their department, and pressure to uphold societal gender roles.13 These barriers produce downstream consequences for many female surgeons as opportunities to obtain titled roles are less likely to be given to women who for personal, educational, or clinical reasons are not able to participate in research.14

More recently, research in the greater academic sphere has demonstrated notable disparities in the number of citations received for articles authored by women vs men. Specifically, Chatterjee et al found that articles authored by women published in high-impact medical journals (eg, New England Journal of Medicine and Journal of American Medical Association) received fewer citations than those authored by men.15 Of these publications, women were also less likely to be primary authors than men and even less likely to be senior authors.16 This discrepancy brings into question the objectivity and presumed meritocracy of scientific communication, that published work is recognized on merit alone.17,18 Citations are a stepping-stone to succession, a widely utilized and accepted metric to gauge scholarly impact, academic success, and academic promotion.15 Therefore, if present, gender bias among citations can contribute to a self-perpetuating barrier to advancement for women.

To understand the current state of citation trends in the field of plastic surgery, we conducted a cross-sectional bibliometric analysis of the 50 most-cited articles published in plastic surgery journals across multiple impact factors between 2017 and 2019. Given the importance and weight that the number of citations carries in academia, we sought to determine whether citation disparities between genders exist. We hypothesized articles written by men as primary and senior authors would be cited more frequently as demonstrated in other medical and academic fields including medicine, urology, gynecologic oncology, neurosurgery, pediatric neurosurgery, neuroscience, psychology, and epidemiology.15,19-26 In addition, because women may face greater barriers to publishing in high-impact journals, we expected disparities in citations to decrease in lower-impact journals as the proportion of women authorship increases.22

METHODS

Articles published between 2017 and 2019 were collected from 8 representative plastic surgery journals: Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Journal of Reconstructive Microsurgery, Microsurgery, Annals of Plastic Surgery, Journal of Plastic Surgery and Hand Surgery, Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Global Open, and Archives of Plastic Surgery. Journals were stratified according to journal impact factor at the time of article collection (August 2021) as high-tier, mid-tier, low-tier, and open access, and were chosen according to both impact factor and discussion among academic plastic surgeons to ensure these were journals that best represented the breadth of publishing options available to authors (Table 1). Journal impact factor was reported from 2020 Journal Impact Factor, Journal Citation Reports (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA). Per journal, the top 50 cited articles were collected per year along with the average number of citations per article using Web of Science 2017-2019 Journal Citation Reports (Clarivate Analytics). All original peer-reviewed articles were included with the exception of clinical guidelines written by expert organizations and not individual authors.

| Tier . | Journal . | Journal impact factor 2020 . |

|---|---|---|

| High | Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery | 4.763 |

| Aesthetic Surgery Journal | 4.283 | |

| Mid | Journal of Reconstructive Microsurgery | 2.873 |

| Microsurgery | 2.425 | |

| Low | Annals of Plastic Surgery | 1.539 |

| Journal of Plastic Surgery and Hand Surgery | 1.462 | |

| Open access | Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Global Open | NA |

| Archives of Plastic Surgery | NA |

| Tier . | Journal . | Journal impact factor 2020 . |

|---|---|---|

| High | Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery | 4.763 |

| Aesthetic Surgery Journal | 4.283 | |

| Mid | Journal of Reconstructive Microsurgery | 2.873 |

| Microsurgery | 2.425 | |

| Low | Annals of Plastic Surgery | 1.539 |

| Journal of Plastic Surgery and Hand Surgery | 1.462 | |

| Open access | Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Global Open | NA |

| Archives of Plastic Surgery | NA |

NA, not applicable.

| Tier . | Journal . | Journal impact factor 2020 . |

|---|---|---|

| High | Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery | 4.763 |

| Aesthetic Surgery Journal | 4.283 | |

| Mid | Journal of Reconstructive Microsurgery | 2.873 |

| Microsurgery | 2.425 | |

| Low | Annals of Plastic Surgery | 1.539 |

| Journal of Plastic Surgery and Hand Surgery | 1.462 | |

| Open access | Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Global Open | NA |

| Archives of Plastic Surgery | NA |

| Tier . | Journal . | Journal impact factor 2020 . |

|---|---|---|

| High | Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery | 4.763 |

| Aesthetic Surgery Journal | 4.283 | |

| Mid | Journal of Reconstructive Microsurgery | 2.873 |

| Microsurgery | 2.425 | |

| Low | Annals of Plastic Surgery | 1.539 |

| Journal of Plastic Surgery and Hand Surgery | 1.462 | |

| Open access | Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Global Open | NA |

| Archives of Plastic Surgery | NA |

NA, not applicable.

The names of the primary and senior authors for each article were collected and gender was determined according to a binary scale (male vs female) via Genderize, a validated online database that uses social network profiles as the gender data source.27,28 The probability of gender classification was also reported by the database, and names where gender could not be classified or did not meet the database threshold of 0.7 were determined through a manual internet search for the author’s name and affiliations. Names that could not be identified via either of these 2 approaches were excluded from the study.

Statistical Analysis

Articles were summarized according to primary and senior authorship, gender, and journal tier. Data were also analyzed by author gender pairings (ie, male primary with male senior, male primary with female senior, etc). Articles written by a single author were only included in the primary authorship analysis. To account for right-skewed citation distribution due to the presence of positive outliers, differences in the median quartile of citations per gender per journal tier were compared.29 Nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used to determine differences between groups with significance set at P < 0.05. All analyses were performed with SPSS 26 (IBM, Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

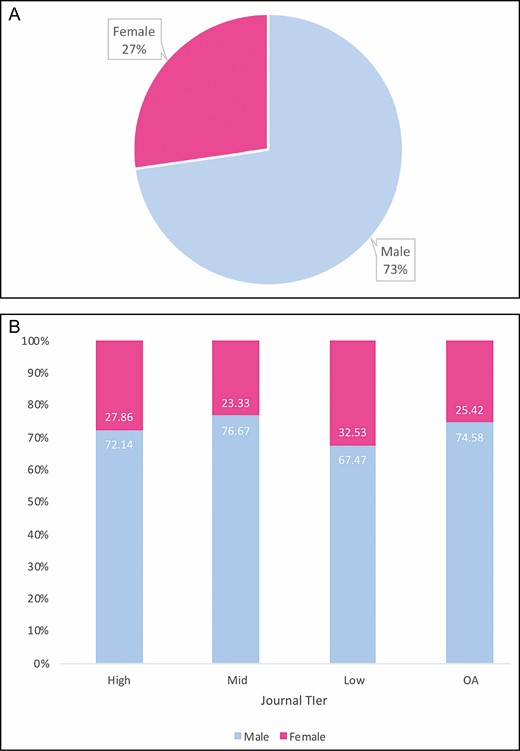

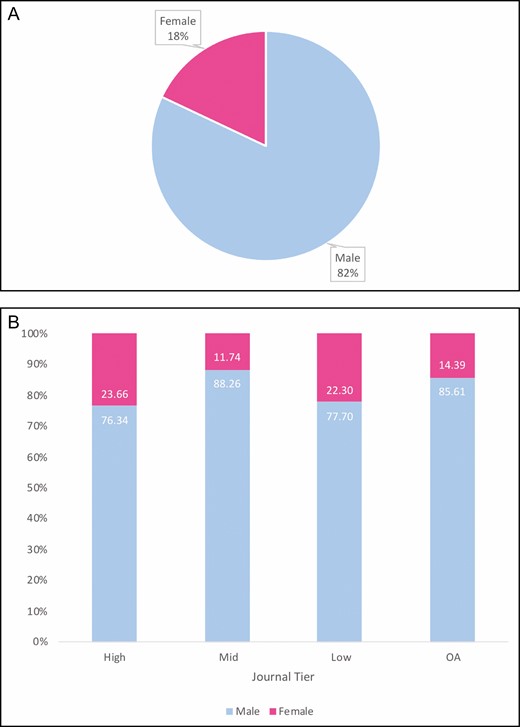

Among 1200 articles collected, 1 article (0.08%) was excluded because it was written by a consortium and 32 (2.7%) articles were excluded because authorship gender could not be identified. Overall, of the 1167 articles that met the inclusion criteria for analysis, women wrote 318 (27.3%) as the primary or only author (Figure 1A). Broken down by tier, women represented 27.9% of primary authorship in high-impact journals, 23.3% in mid-impact journals, 32.5% in low-impact journals, and 25.4% in open access journals (Figure 1B) There were 1151 articles that had 2 or more authors where senior authorship could be analyzed. Of these, women represented 207 (18%) of senior authorship (Table 2, Figure 2A). Women represented even less of senior authorship across each impact tier with 23.7% senior female authors in high-impact journals, 11.7% in mid-impact journals, 22.3% in low-impact journals, and 14.4% in open access journals (Table 3, Figure 2B).

Proportion of Authorship and Number of Citations by Author Role and Author Pairing

| Author level . | Gender . | N (%) . | Average number of citations per year [SD] . | Median quartile . | Pa . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary author | Male | 849 (72.8) | 3.77 [3.46] | 2.60 | 0.939 |

| Female | 318 (27.2) | 4.07 [4.12] | 2.78 | ||

| Total | 1167.00 | — | — | ||

| Senior author | Male | 944 (82%) | 3.63 [3.60] | 2.60 | 0.276 |

| Female | 207 (18%) | 3.90 [3.28] | 2.80 | ||

| Total | 1151.00 | — | — | ||

| Authorship pairings | MMb | 688 (65.8%) | 3.46 [3.22] | 2.55 | 0.022 |

| FMb | 151 (14.4%) | 4.20 [4.47] | 2.80 | ||

| MF | 126 (12.1%) | 3.84 [3.36] | 2.80 | ||

| FF | 81 (7.7%) | 4.05 [3.13] | 3.00 | ||

| Total | 1046.00 | — | — |

| Author level . | Gender . | N (%) . | Average number of citations per year [SD] . | Median quartile . | Pa . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary author | Male | 849 (72.8) | 3.77 [3.46] | 2.60 | 0.939 |

| Female | 318 (27.2) | 4.07 [4.12] | 2.78 | ||

| Total | 1167.00 | — | — | ||

| Senior author | Male | 944 (82%) | 3.63 [3.60] | 2.60 | 0.276 |

| Female | 207 (18%) | 3.90 [3.28] | 2.80 | ||

| Total | 1151.00 | — | — | ||

| Authorship pairings | MMb | 688 (65.8%) | 3.46 [3.22] | 2.55 | 0.022 |

| FMb | 151 (14.4%) | 4.20 [4.47] | 2.80 | ||

| MF | 126 (12.1%) | 3.84 [3.36] | 2.80 | ||

| FF | 81 (7.7%) | 4.05 [3.13] | 3.00 | ||

| Total | 1046.00 | — | — |

SD, standard deviation; FF, female primary with female senior author; FM, female primary with male senior author; MF, male primary author with female senior author; MM, male primary with male senior author.

aP value corresponds to 1-tailed nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test for authorship pairings.

bP value between MM and FM = 0.034; P > 0.05 for all other pairing comparisons.

Proportion of Authorship and Number of Citations by Author Role and Author Pairing

| Author level . | Gender . | N (%) . | Average number of citations per year [SD] . | Median quartile . | Pa . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary author | Male | 849 (72.8) | 3.77 [3.46] | 2.60 | 0.939 |

| Female | 318 (27.2) | 4.07 [4.12] | 2.78 | ||

| Total | 1167.00 | — | — | ||

| Senior author | Male | 944 (82%) | 3.63 [3.60] | 2.60 | 0.276 |

| Female | 207 (18%) | 3.90 [3.28] | 2.80 | ||

| Total | 1151.00 | — | — | ||

| Authorship pairings | MMb | 688 (65.8%) | 3.46 [3.22] | 2.55 | 0.022 |

| FMb | 151 (14.4%) | 4.20 [4.47] | 2.80 | ||

| MF | 126 (12.1%) | 3.84 [3.36] | 2.80 | ||

| FF | 81 (7.7%) | 4.05 [3.13] | 3.00 | ||

| Total | 1046.00 | — | — |

| Author level . | Gender . | N (%) . | Average number of citations per year [SD] . | Median quartile . | Pa . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary author | Male | 849 (72.8) | 3.77 [3.46] | 2.60 | 0.939 |

| Female | 318 (27.2) | 4.07 [4.12] | 2.78 | ||

| Total | 1167.00 | — | — | ||

| Senior author | Male | 944 (82%) | 3.63 [3.60] | 2.60 | 0.276 |

| Female | 207 (18%) | 3.90 [3.28] | 2.80 | ||

| Total | 1151.00 | — | — | ||

| Authorship pairings | MMb | 688 (65.8%) | 3.46 [3.22] | 2.55 | 0.022 |

| FMb | 151 (14.4%) | 4.20 [4.47] | 2.80 | ||

| MF | 126 (12.1%) | 3.84 [3.36] | 2.80 | ||

| FF | 81 (7.7%) | 4.05 [3.13] | 3.00 | ||

| Total | 1046.00 | — | — |

SD, standard deviation; FF, female primary with female senior author; FM, female primary with male senior author; MF, male primary author with female senior author; MM, male primary with male senior author.

aP value corresponds to 1-tailed nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test for authorship pairings.

bP value between MM and FM = 0.034; P > 0.05 for all other pairing comparisons.

Number of Citations per Primary and Senior Author Gender, Stratified by Journal Impact Tier

| Journal impact tier . | Author role . | Author gender . | N (%) . | Average number of citations per year [SD] . | Median quartile . | Pa . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High impact | Primary | Male | 202 (72.1%) | 6.34 [4.28] | 5.75 | 0.137 |

| Female | 78 (27.9%) | 7.69 [6.21] | 6.47 | |||

| Mid impact | Male | 230 (76.2%) | 3.58 [3.18] | 2.40 | 0.971 | |

| Female | 70 (23.3%) | 2.82 [1.71] | 2.82 | |||

| Low impact | Male | 197 (67.5%) | 2.66 [2.62] | 2.25 | 0.115 | |

| Female | 95 (32.5%) | 2.75 [2.27] | 2.75 | |||

| Open access | Male | 220 (74.6) | 2.58 [2.01] | 2.33 | 0.147 | |

| Female | 75 (25.4%) | 3.09 [2.19] | 3.09 | |||

| High impact | Senior | Male | 213 (76.3%) | 6.29 [5.20] | 6.00 | 0.774 |

| Female | 66 (23.7%) | 6.29 [4.19] | 5.88 | |||

| Mid impact | Male | 263 (88.3%) | 2.66 [1.83] | 2.25 | 0.17 | |

| Female | 35 (11.7%) | 2.72 [1.20] | 2.50 | |||

| Low impact | Male | 230 (77.7%) | 2.59 [2.58] | 2.25 | 0.132 | |

| Female | 66 (22.3%) | 2.91 [2.19] | 2.38 | |||

| Open access | Male | 238 (85.6%) | 2.74 [2.11] | 2.40 | 0.981 | |

| Female | 40 (14.4%) | 2.61 [2.02] | 2.20 |

| Journal impact tier . | Author role . | Author gender . | N (%) . | Average number of citations per year [SD] . | Median quartile . | Pa . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High impact | Primary | Male | 202 (72.1%) | 6.34 [4.28] | 5.75 | 0.137 |

| Female | 78 (27.9%) | 7.69 [6.21] | 6.47 | |||

| Mid impact | Male | 230 (76.2%) | 3.58 [3.18] | 2.40 | 0.971 | |

| Female | 70 (23.3%) | 2.82 [1.71] | 2.82 | |||

| Low impact | Male | 197 (67.5%) | 2.66 [2.62] | 2.25 | 0.115 | |

| Female | 95 (32.5%) | 2.75 [2.27] | 2.75 | |||

| Open access | Male | 220 (74.6) | 2.58 [2.01] | 2.33 | 0.147 | |

| Female | 75 (25.4%) | 3.09 [2.19] | 3.09 | |||

| High impact | Senior | Male | 213 (76.3%) | 6.29 [5.20] | 6.00 | 0.774 |

| Female | 66 (23.7%) | 6.29 [4.19] | 5.88 | |||

| Mid impact | Male | 263 (88.3%) | 2.66 [1.83] | 2.25 | 0.17 | |

| Female | 35 (11.7%) | 2.72 [1.20] | 2.50 | |||

| Low impact | Male | 230 (77.7%) | 2.59 [2.58] | 2.25 | 0.132 | |

| Female | 66 (22.3%) | 2.91 [2.19] | 2.38 | |||

| Open access | Male | 238 (85.6%) | 2.74 [2.11] | 2.40 | 0.981 | |

| Female | 40 (14.4%) | 2.61 [2.02] | 2.20 |

SD, standard deviation.

aP value corresponds to 1-tailed nonparametric independent-samples Kruskal-Wallis test.

Number of Citations per Primary and Senior Author Gender, Stratified by Journal Impact Tier

| Journal impact tier . | Author role . | Author gender . | N (%) . | Average number of citations per year [SD] . | Median quartile . | Pa . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High impact | Primary | Male | 202 (72.1%) | 6.34 [4.28] | 5.75 | 0.137 |

| Female | 78 (27.9%) | 7.69 [6.21] | 6.47 | |||

| Mid impact | Male | 230 (76.2%) | 3.58 [3.18] | 2.40 | 0.971 | |

| Female | 70 (23.3%) | 2.82 [1.71] | 2.82 | |||

| Low impact | Male | 197 (67.5%) | 2.66 [2.62] | 2.25 | 0.115 | |

| Female | 95 (32.5%) | 2.75 [2.27] | 2.75 | |||

| Open access | Male | 220 (74.6) | 2.58 [2.01] | 2.33 | 0.147 | |

| Female | 75 (25.4%) | 3.09 [2.19] | 3.09 | |||

| High impact | Senior | Male | 213 (76.3%) | 6.29 [5.20] | 6.00 | 0.774 |

| Female | 66 (23.7%) | 6.29 [4.19] | 5.88 | |||

| Mid impact | Male | 263 (88.3%) | 2.66 [1.83] | 2.25 | 0.17 | |

| Female | 35 (11.7%) | 2.72 [1.20] | 2.50 | |||

| Low impact | Male | 230 (77.7%) | 2.59 [2.58] | 2.25 | 0.132 | |

| Female | 66 (22.3%) | 2.91 [2.19] | 2.38 | |||

| Open access | Male | 238 (85.6%) | 2.74 [2.11] | 2.40 | 0.981 | |

| Female | 40 (14.4%) | 2.61 [2.02] | 2.20 |

| Journal impact tier . | Author role . | Author gender . | N (%) . | Average number of citations per year [SD] . | Median quartile . | Pa . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High impact | Primary | Male | 202 (72.1%) | 6.34 [4.28] | 5.75 | 0.137 |

| Female | 78 (27.9%) | 7.69 [6.21] | 6.47 | |||

| Mid impact | Male | 230 (76.2%) | 3.58 [3.18] | 2.40 | 0.971 | |

| Female | 70 (23.3%) | 2.82 [1.71] | 2.82 | |||

| Low impact | Male | 197 (67.5%) | 2.66 [2.62] | 2.25 | 0.115 | |

| Female | 95 (32.5%) | 2.75 [2.27] | 2.75 | |||

| Open access | Male | 220 (74.6) | 2.58 [2.01] | 2.33 | 0.147 | |

| Female | 75 (25.4%) | 3.09 [2.19] | 3.09 | |||

| High impact | Senior | Male | 213 (76.3%) | 6.29 [5.20] | 6.00 | 0.774 |

| Female | 66 (23.7%) | 6.29 [4.19] | 5.88 | |||

| Mid impact | Male | 263 (88.3%) | 2.66 [1.83] | 2.25 | 0.17 | |

| Female | 35 (11.7%) | 2.72 [1.20] | 2.50 | |||

| Low impact | Male | 230 (77.7%) | 2.59 [2.58] | 2.25 | 0.132 | |

| Female | 66 (22.3%) | 2.91 [2.19] | 2.38 | |||

| Open access | Male | 238 (85.6%) | 2.74 [2.11] | 2.40 | 0.981 | |

| Female | 40 (14.4%) | 2.61 [2.02] | 2.20 |

SD, standard deviation.

aP value corresponds to 1-tailed nonparametric independent-samples Kruskal-Wallis test.

Proportion of primary authorship by gender (A) across all journals and (B) stratified by journal impact factor tier.

Proportion of senior authorship by gender (A) across all journals and (B) stratified by journal impact factor tier.

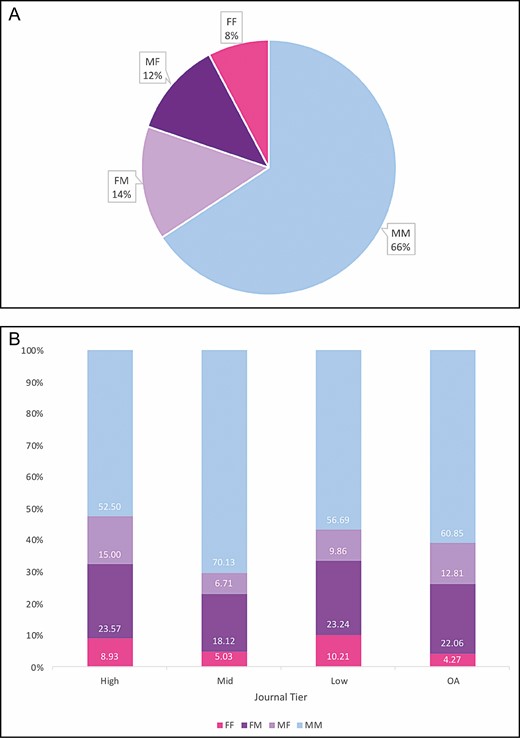

When analyzed by authorship pairings, male primary with male senior (MM) author comprised 65.8% of the articles across all journals, female primary with male senior (FM) comprised 14.4%, male primary with female senior (MF) comprised 12.1%, and female primary with female senior (FF) comprised 7.7% (Table 2, Figure 3A). Within each journal impact factor tier, MM represented 52.5% of authorship in high-impact journals, FM represented 23.6%, MF represented 15%, and FF represented 8.9%. In mid-impact journals, MM represented 70.1% of authorship, FM represented 18.1%, MF represented 6.7%, and FF represented 5%. Similarly in low-impact journals, MM represented 56.7% of authorship, FM represented 23.2%, MF represented 9.9%, and FF represented 4.3%. Authorship in open access journals was primarily MM with 60.9% of articles, followed by FM with 22.1%, then MF with 12.8%, and FF with 4.3% (Figure 3B).

Proportion of author pairings by gender (A) across all journals and (B) stratified by journal impact factor tier. FF, female primary with female senior author; FM, female primary with male senior author; MF, male primary author with female senior author; MM, male primary with male senior author.

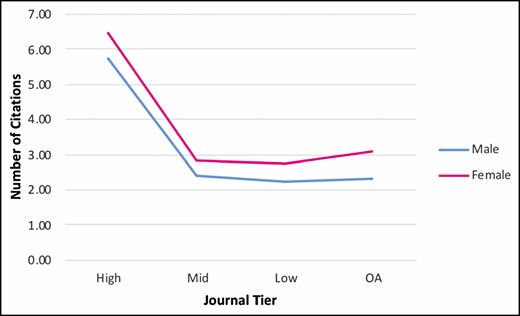

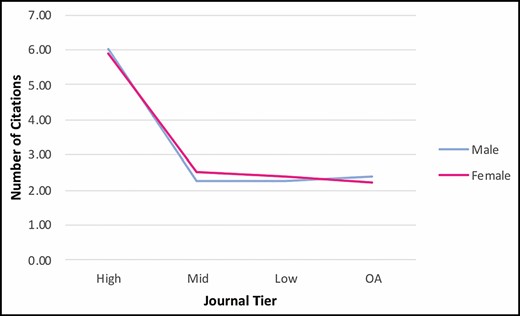

Citation trends were analyzed according to primary and senior authors as well as by author pairing. Across all journal impact tiers, the number of citations in the median quartile for articles with a female primary author were not significantly different from those written by men (2.78 vs 2.6, P = 0.939). Similarly, the number of citations in the median quartile for articles with female senior authorship were not significantly different than those authored by male senior authors (2.6 vs 2.6, P = 0.147) (Table 2). Stratified by journal impact tier, there was no significant difference between the number of citations of articles with female primary authors vs male primary authors in high-impact (6.47 vs 5.75, P = 0.137), mid-impact (2.82 vs 2.40, P = 0.971), low-impact (2.75 vs 2.25, P = 0.741), or open access (3.09 vs 2.33, P = 0.115) journals (Figure 4). There was no significant difference between the number of citations of articles with female senior authorship vs male senior authorship across high-impact (5.88 vs 6.0, P = 0.774), mid-impact (2.5 vs 2.25, P = 0.117), low-impact (2.38 vs 2.25, P = 0.132), or open access (2.20 vs 2.40, P = 0.981) journals (Table 3, Figure 5).

Number of citations (median quartile) per primary author stratified by journal tier. No significant difference was found between number of citations (median quartile) among male and female primary authors at each journal tier.

Number of citations (median quartile) per senior author stratified by journal tier. No significant difference was found between number of citations (median quartile) among male and female senior authors at each journal tier.

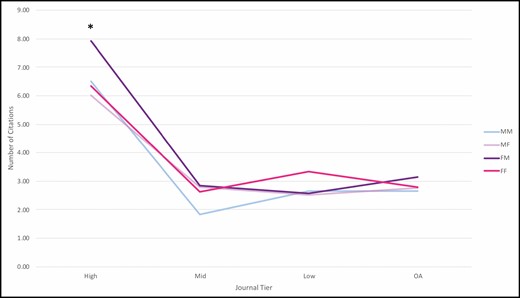

Across all journal tiers, there was a significant difference in number of citations when stratified by authorship pairings (P = 0.022) (Table 2). Specifically, articles written by female primary and male senior authors were cited significantly more than those written by male primary and male senior authors (3.0 vs 2.67, P = 0.034) (Figure 6). There was no significant difference in citation frequency between authorship pairings when stratified by impact factor for high-impact (P = 0.731), mid-impact (P = 0.917), low-impact (P = 0.865), and open access (P = 0.541) journals (Table 4).

| Level . | Author pairing . | N (%) . | Average number of citations per year [SD] . | Median quartile . | Pa . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High impact | MM | 147 (52.5%) | 25.95 [19.99] | 6.00 | 0.731 |

| MF | 42 (15%) | 25.76 [22.89] | 5.67 | ||

| FM | 66 (23.6%) | 32.06 [32.69] | 6.17 | ||

| FF | 25 (8.9%) | 27.28 [19.25] | 6.33 | ||

| Mid impact | MM | 209 (70.1%) | 10.76 [8.60] | 2.20 | 0.917 |

| MF | 20 (6.7%) | 11.90 [6.49] | 2.45 | ||

| FM | 54 (18.1%) | 11.17 [8.74] | 2.25 | ||

| FF | 15 (5.1%) | 9.40 [4.47] | 2.50 | ||

| Low impact | MM | 161 (56.7%) | 11.12 [13.57] | 2.20 | 0.865 |

| MF | 28 (9.9%) | 11.04 [9.21] | 2.25 | ||

| FM | 66 (23.2%) | 10.27 [9.36] | 2.42 | ||

| FF | 29 (10.2%) | 14.07 [11.23] | 2.50 | ||

| Open access | MM | 171 (60.9%) | 10.58 [9.14] | 2.33 | 0.541 |

| MF | 36 (12.8%) | 11.93 [8.26] | 2.68 | ||

| FM | 62 (22.1%) | 11.86 [9.81] | 2.71 | ||

| FF | 12 (4.3%) | 12.54 [9.61] | 2.50 |

| Level . | Author pairing . | N (%) . | Average number of citations per year [SD] . | Median quartile . | Pa . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High impact | MM | 147 (52.5%) | 25.95 [19.99] | 6.00 | 0.731 |

| MF | 42 (15%) | 25.76 [22.89] | 5.67 | ||

| FM | 66 (23.6%) | 32.06 [32.69] | 6.17 | ||

| FF | 25 (8.9%) | 27.28 [19.25] | 6.33 | ||

| Mid impact | MM | 209 (70.1%) | 10.76 [8.60] | 2.20 | 0.917 |

| MF | 20 (6.7%) | 11.90 [6.49] | 2.45 | ||

| FM | 54 (18.1%) | 11.17 [8.74] | 2.25 | ||

| FF | 15 (5.1%) | 9.40 [4.47] | 2.50 | ||

| Low impact | MM | 161 (56.7%) | 11.12 [13.57] | 2.20 | 0.865 |

| MF | 28 (9.9%) | 11.04 [9.21] | 2.25 | ||

| FM | 66 (23.2%) | 10.27 [9.36] | 2.42 | ||

| FF | 29 (10.2%) | 14.07 [11.23] | 2.50 | ||

| Open access | MM | 171 (60.9%) | 10.58 [9.14] | 2.33 | 0.541 |

| MF | 36 (12.8%) | 11.93 [8.26] | 2.68 | ||

| FM | 62 (22.1%) | 11.86 [9.81] | 2.71 | ||

| FF | 12 (4.3%) | 12.54 [9.61] | 2.50 |

SD, standard deviation; FF, female primary with female senior author; FM, female primary with male senior author; MM, Male primary with male senior author; MF, male primary author with female senior author.

aP value corresponds to 1-tailed nonparametric independent-samples Kruskal-Wallis test.

| Level . | Author pairing . | N (%) . | Average number of citations per year [SD] . | Median quartile . | Pa . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High impact | MM | 147 (52.5%) | 25.95 [19.99] | 6.00 | 0.731 |

| MF | 42 (15%) | 25.76 [22.89] | 5.67 | ||

| FM | 66 (23.6%) | 32.06 [32.69] | 6.17 | ||

| FF | 25 (8.9%) | 27.28 [19.25] | 6.33 | ||

| Mid impact | MM | 209 (70.1%) | 10.76 [8.60] | 2.20 | 0.917 |

| MF | 20 (6.7%) | 11.90 [6.49] | 2.45 | ||

| FM | 54 (18.1%) | 11.17 [8.74] | 2.25 | ||

| FF | 15 (5.1%) | 9.40 [4.47] | 2.50 | ||

| Low impact | MM | 161 (56.7%) | 11.12 [13.57] | 2.20 | 0.865 |

| MF | 28 (9.9%) | 11.04 [9.21] | 2.25 | ||

| FM | 66 (23.2%) | 10.27 [9.36] | 2.42 | ||

| FF | 29 (10.2%) | 14.07 [11.23] | 2.50 | ||

| Open access | MM | 171 (60.9%) | 10.58 [9.14] | 2.33 | 0.541 |

| MF | 36 (12.8%) | 11.93 [8.26] | 2.68 | ||

| FM | 62 (22.1%) | 11.86 [9.81] | 2.71 | ||

| FF | 12 (4.3%) | 12.54 [9.61] | 2.50 |

| Level . | Author pairing . | N (%) . | Average number of citations per year [SD] . | Median quartile . | Pa . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High impact | MM | 147 (52.5%) | 25.95 [19.99] | 6.00 | 0.731 |

| MF | 42 (15%) | 25.76 [22.89] | 5.67 | ||

| FM | 66 (23.6%) | 32.06 [32.69] | 6.17 | ||

| FF | 25 (8.9%) | 27.28 [19.25] | 6.33 | ||

| Mid impact | MM | 209 (70.1%) | 10.76 [8.60] | 2.20 | 0.917 |

| MF | 20 (6.7%) | 11.90 [6.49] | 2.45 | ||

| FM | 54 (18.1%) | 11.17 [8.74] | 2.25 | ||

| FF | 15 (5.1%) | 9.40 [4.47] | 2.50 | ||

| Low impact | MM | 161 (56.7%) | 11.12 [13.57] | 2.20 | 0.865 |

| MF | 28 (9.9%) | 11.04 [9.21] | 2.25 | ||

| FM | 66 (23.2%) | 10.27 [9.36] | 2.42 | ||

| FF | 29 (10.2%) | 14.07 [11.23] | 2.50 | ||

| Open access | MM | 171 (60.9%) | 10.58 [9.14] | 2.33 | 0.541 |

| MF | 36 (12.8%) | 11.93 [8.26] | 2.68 | ||

| FM | 62 (22.1%) | 11.86 [9.81] | 2.71 | ||

| FF | 12 (4.3%) | 12.54 [9.61] | 2.50 |

SD, standard deviation; FF, female primary with female senior author; FM, female primary with male senior author; MM, Male primary with male senior author; MF, male primary author with female senior author.

aP value corresponds to 1-tailed nonparametric independent-samples Kruskal-Wallis test.

Number of citations (median quartile) per author pairing stratified by journal tier. There is a significant difference (*) between all authorship pairings in high-impact journals (P = 0.022). Specifically, articles with a male senior author and female primary author had more citations than those with a male primary author (P = 0.034). Significance was not determined across authorship pairings at any other tier. FF, female primary with female senior author; FM, female primary with male senior author; MF, male primary author with female senior author; MM, male primary with male senior author.

DISCUSSION

Citations are a measure of success in academia; they are used as a surrogate for innovation, research quality, and novelty.18 Although controversial, citation metrics are often used to measure an individual’s performance, affect academic promotion, and inform hiring decisions, in part because they are perceived as an unbiased reflection of merit.16,17,30-34 Therefore, to better understand current gender inequity in academic plastic surgery we assessed citation metrics across representative journals with varying journal impact factors for the presence of gender bias.

This is the first study to demonstrate the absence of gender bias among citation trends in the most-cited articles in the field of plastic surgery, a hopeful and encouraging finding.35,36 Unlike other data in various biomedical fields, we found articles with women authorship were cited similarly to those authored by men despite female authors comprising a smaller fraction of published authorship overall.11,19,20 Citation trends did not vary across journal impact factor. However, when compared across tiers, there was a higher percentage of female senior authors in the high impact tier.

Articles with a female primary author and male senior author received significantly more citations than when authorship pairings were homogeneous (ie, male primary and male senior author). This finding is in line with overwhelming evidence that variegated groups outperform homogeneous ones on problem solving and increased innovation as including people who hold varied lived experiences and perspectives generates robust and novel findings.37,38

Although gender bias remains ubiquitous across surgical disciplines, the gender gap in plastic surgery is narrowing compared with other surgical subspecialties, including orthopedic, cardiothoracic, urology, vascular, and neurosurgery.39,40 Between 2000 and 2013 the number of female surgeons increased from 15% to 25%, with plastic surgery showing one of the largest increases in overall female representation.41 From 2008 to 2015, the female-to-male proportion of integrated plastic surgery residents increased from 1:3.1 to 1:1.4 compared with neurosurgery and orthopedic surgery which have remained relatively stagnant.41 The proportion of female to male board-certified plastic surgeons also increased during this time from 1:9.1 to 1:5.3.41 A similar increase would be expected in gender representation among all certified plastic surgeons; however, we were unable to find any report at the time of publication. Although equitable representation has yet to be achieved, academic plastic surgery exhibits significant growth which may contribute to the lack of bias found in this study.

Although the percentage of female primary authorship exceeds the number of board-certified female plastic surgeons, it is much less than the percentage of female plastic surgery trainees (~40% over the past 4 years) who are most often first authors. However, despite female senior authorship being lower than the number of total board-certified female plastic surgeons, it does exceed the number of female academic plastic surgery faculty who are more likely to be senior authors in the first place. Furthermore, the impact of women-led work surpasses that of representation alone, illustrated by the fact that women comprise over 27% of senior authorship of the most-cited articles in the highest-impact journals, despite only making up 12.3% of academic board-certified plastic surgeons.9

As more women fill plastic surgery residency and faculty positions, it is important to remember that gender equity goes beyond merely the number of women within plastic surgery and must be met by a rise in gender inclusion. As evidenced by our data, women contribute meaningfully to plastic surgery literature yet comprise a smaller proportion of academic authorship. When stratified by topic, differences are elucidated further. Gunderson et al found that although women authorship has experienced notable increases in the Breast section of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, women author representation in the Cosmetic and Hand/Peripheral Nerve sections remains stagnant.42 This may be explained by the fact that the Breast section is the largest by volume compared with the other topics.

Therefore, future work needs to address specific barriers women face in academia, specifically along the publication pathway. For example, conducting quality research takes time, money, and mentorship. Because of the societal pressures of gender roles ascribed to them, women often defer research opportunities to devote more time to family obligations.14 Additionally, women are less likely to apply for grant funding and, when they do, receive less than their male colleagues.43 Lack of mentorship can also deter women from participating in research. Despite being more likely to benefit from same-gender mentorship, only 15% of women had a same-gender mentor.1,44 Disparities in perceived departmental support can also discourage women from conducting research as women surgeons are less likely to be promoted and tend to make less money than their male peers for doing the same quantity and caliber of work.45-48

Editorial decisions and the peer-review process is another stop in the publication pathway where female authors may face bias. In general, women are underrepresented on editorial boards and as editors in chief among leading medical and surgical journals.49,50 In 2019 women comprised 18.7% of editorial boards and 11.5% of associate editors in leading plastic surgery journals.50 A few journals, such as Aesthetic Surgery Journal, demonstrate more equitable representation among authorship and editorial board gender diversity.51-53 Even if review processes are blinded (which is typically not the case), studies show that gender preferences persist in the peer-review practice.36,54 In one study investigating the impact author gender has on perceived quality of scientific publications, male authors’ contributions were associated with greater scientific quality despite the actual content being rotated to control for confounding factors.54 Other studies demonstrate that women are often seen as less competent and evaluated more harshly than their male peers.55-57 Considering the lack of female representation among the stewards of scholarly work, research led by women within plastic surgery may be less likely to be selected for publication by journals who do not offer a double-blinded peer-review process and therefore reviewers and/or editors are aware of the gender of the authors during peer review and implicit bias may occur. Similarly, publishing decisions are influenced by authors’ social, professional, and collaborative networks where male researchers are more likely to collaborate with male peers and female researchers are more likely to collaborate with their female peers.26 Therefore gender disparities in academia self-perpetuate.

In light of these findings, we advocate for increased transparency among the article review process to control for authorship gender bias. As evidenced by the Aesthetic Surgery Journal, which was the only journal included in this study that provided information on its website detailing its double-blinded review process, increased transparency increases accountability which may in part diminish gender bias.51-53,58

There are limitations to this study worth noting. Gender was assessed according to a binary scale (male vs female) and does not represent the full spectrum of possible author gender identities. Additionally, gender was categorized according to the probability of the author’s first name appearing in verified social media accounts which may be discordant with their gender identity. Impact factor was also used to categorize journal prestige, as where authors publish has the potential to influence promotion and funding.59 However, impact factor is frequently criticized as it insufficiently captures the totality and nuances of a journal’s merit and therefore subsequent analysis using impact factor will also suffer the same limitations.60,61 The cross-sectional design of the study also limited the scope and time frame of the analysis.

CONCLUSIONS

When women overcome the multiple barriers along the publishing pathway, their contribution becomes integral to the advancement of plastic surgery; diversity indeed drives innovation. This is the first study to demonstrate the absence of gender bias among citation trends in plastic surgery literature, a finding unique in the field of surgery. Moreover, female authorship is best represented in high-impact journals where female primary authors are cited more often than male primary authors. Although encouraging, women authorship continues to be underrepresented in plastic surgery literature as a whole. As the field of plastic surgery continues to grow in gender diversity, it must also grow in gender inclusion. Our hope is that this study serves as both an affirmation and celebration of the contributions women make to plastic surgery as well as an impetus to dismantle the systemic barriers inhibiting them from publishing in the first place.

Disclosures

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.