-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Meredith G Moore, Kyle W Singerman, William J Kitzmiller, Ryan M Gobble, Gender Disparity in 2013-2018 Industry Payments to Plastic Surgeons, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 41, Issue 11, November 2021, Pages 1316–1320, https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjaa367

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The gender pay gap in medicine has been under intense scrutiny in recent years; female plastic surgeons reportedly earn 11% less than their male peers. “Hidden” pay in the form of industry-based transfers exposes compensation disparity not captured by traditional wage-gap estimations.

The aim of this study was to reveal the sex distribution of industry payments to board-certified plastic surgeons across all years covered by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services Open Payment Database (CMS OPD).

We obtained the National Provider Identifier (NPI) for each surgeon in the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) member directory to record gender. Next, “General Payments” data points from annual files for all years present in the CMS OPD, 2013 to 2018, were aggregated and joined to provider details by Physician Profile ID before quantitative analysis was performed.

Of 4840 ASPS surgeons, 3864 (79.8%) reporting ≥1 industry payment were included with 3220 male (83.3%) and 644 female (16.7%). Over 2013 to 2018, females received mean [standard deviation] 56.01 [2.51] payments totaling $11,530.67 [$1461.45] each vs 65.70 [1.80] payments totaling $25,469.05 [$5412.60] for males. The yearly ratio of male-to-female payments in dollars was 2.36 in 2013, 2.69 in 2014, 2.53 in 2015, 2.31 in 2016, 1.72 in 2017, and most recently 1.96 in 2018.

Individual male plastic surgeons received over twice the payment dollars given to their female counterparts, accepting both more frequent and higher-value transfers from industry partners. Payment inequity slightly declined in recent years, which may indicate shifting industry engagement gender preferences.

There is great potential for industry involvement in the innovative field of plastic surgery. In fact, plastic surgeons are often the department members most frequently compensated by industry across surgical departments at large.1 All industry payments to US plastic surgeons since 2013 are now publicly available thanks to the Physician Payments Sunshine Act of 2010 mandating reporting of any payment >$10 from a drug or device company.2 These payment records sit within the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services Open Payments Database (CMS OPD). Most transactions catalogued here fall under the “General” category, which includes all cash and cash equivalents. Mandatory reporting to CMS drives transparency regarding the relationship between physicians and industry, yet little has been studied about specific recipient characteristics, including gender, within plastic surgery.

The gender pay gap in medicine has been under intense scrutiny in recent years. Investigations into traditional compensation trends in the field of plastic surgery have elucidated a gender wage gap in which females earn 11% less than their peers.3 However, not much is known about the industry payments that plastic surgeons receive in addition to their reported salary and how these may abide by male-female divides. To this end, “hidden” compensation publicly reported under the Physician Payments Sunshine Act may exacerbate gender wage gaps.

Female representation within plastic surgery resident trainees has grown year-on-year for the past 7 years.4 As females become a larger part of our workforce, it bears relevance to examine whether their “soft” compensation is equivalent to that of males. Previous studies repeatedly demonstrate sizeable salary discrepancies between female and male surgeons,5-9 and existing work in various surgical subspecialties suggests that this gap applies to industry payments as well.10-13

A longitudinal analysis of industry support of plastic surgeons via the CMS OPD for all reporting years to date has not yet been conducted with respect to gender. Six years of records of industry payments to plastic surgeons over the 2013 to 2018 period may reveal certain preferences in corporate physician relationships with implications for gender equity in the field; in light of this, we aimed to investigate the sex distribution of general industry payments to board-certified plastic surgeons across all years covered by the CMS OPD.

METHODS

Overview

The 2019 membership of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS), as a preeminent professional organization for our field, was used as the population sample for this observational, retrospective study of plastic surgeons with CMS OPD entries. Records were pulled from the online database at https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/ by one of the authors (M.G.M.). Specific payment parameters are available regarding the amount, form of payment, date of payment, payment purpose, and physician practice specialization, and so on. Payment records are available dating back to the 2013 calendar year, and each transfer is indexed to a recipient physician’s personal Payment Profile Identifier (PPI).

No funding was received to conduct this study.

Study Population

The inclusion cohort comprised all physicians searchable on the online ASPS Find A Surgeon tool (https://find.plasticsurgery.org/) on September 1, 2019. Physicians based in all US states and territories were recorded. Surgeons in this group were cross-referenced with those in the CMS OPD “Physician Supplement File for All Program Years” file, which contains the names of all physicians who were paid the equivalent of over US$10 on at least 1 occasion over the period from August 1, 2013 to December 31, 2018. Surgeons were matched by PPI; those without a listed PPI were manually searched on the CMS OPD online search tool by first and last name, with further verification by practice location. Despite being listed, 32 surgeons present in the CMS OPD had a zero-dollar payment total for the study period and hence were excluded from the final cohort.

Physician full name, geographic practice information (state, 5-digit practice zip code), and American Board of Plastic Surgery certification year were recorded from the ASPS Find A Surgeon tool. Corresponding National Provider Identifier (NPI) (https://npiregistry.cms.hhs.gov/) was then identified for each recipient. The NPI listing was utilized for definitive gender classification and verification of physician practice location. The state and zip code of the primary practice site was recorded for those surgeons with multiple practices associated with their NPI number.

Payment Data

General Payments datasets for all years available were downloaded from the CMS OPD. This category includes all forms of payment (eg, speaking fees, food, and beverage), excluding only those transfers categorized as Research Payments or Ownership Interests (https://www.cms.gov/OpenPayments/FAQs/FAQs-openpayments). Figures in US dollars from these CMS OPD General Payments were aggregated by annual amounts for each individual year queried and then joined by PPI to the surgeon demographic database in Tableau (Seattle, WA) data visualization software. Quantity of payments and payment total for the study period were tabulated as payment variables for each PPI (ie, each surgeon) and then counted by sex. Additional calculated variables included annual payment aggregated total, number of payments by year, totals by form of payment (cash or cash equivalent vs in-kind designation), and figures by gender group. Additionally, we directly compared payment totals between gender groups by calculating a male-to-female ratio.

Statistical Analyses

Payment differences between ASPS-affiliated plastic surgeons of each gender were assessed by single-factor analysis of variance and 2-tailed t test assuming equal variances. Statistical significance level was set at P < 0.05. Descriptive statistics such as mean, median, and mode were computed for quantitative payment variables.

RESULTS

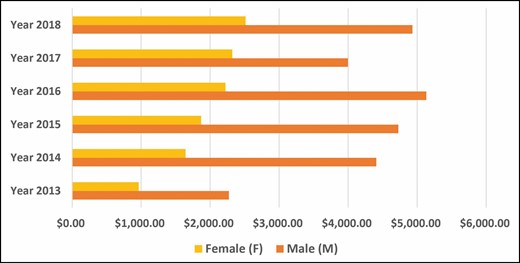

The composite database of physicians with a nonzero payment sum numbered 3864, which amounts to 79.8% of the 4840 ASPS members catalogued. Within this group, the sex distribution of 83.3% male and 16.7% female mirrored that of the other remaining 976 ASPS members who had never received payments (male, 86.0%; female, 14.0%). Of female surgeons, 82.5% (644 of 781) were paid by industry at least once over the study period; for males, this figure was 79.4% (3224 of 4063). Mean [standard deviation] total funds transferred to men (N = 3220) was $25,468.05 [$5412], and to women (N = 644) $11,530.67 [$11,461.45] (Table 1, Figure 1). Both distributions had a positive skew. Mean number of payments to men was 65.7 [1.8] vs 56.0 [2.5] for women. Average dollars per payment over the study period was $387.68 for male plastic surgeons and $205.85 for female plastic surgeons. Earnings ratios between the genders ranged from male:female 1.72 in 2017 to 2.69 in 2014, with this ratio equaling 2.21 when calculated for all payments received over the entire study period (Table 1).

| Surgeon gender . | Payments ($) . | Individual payment mean ($) . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | 2013 . | 2014 . | 2015 . | 2016 . | 2017 . | 2018 . | 2013-2018 . | . |

| Male | 2272.83 | 4409.40 | 4726.84 | 5134.25 | 3995.04 | 4930.69 | 25,469.05 | 387.68 |

| Female | 963.45 | 1641.99 | 1870.36 | 2220.68 | 2319.97 | 2514.21 | 11,530.67 | 205.85 |

| Male:female payment ratio | 2.36 | 2.69 | 2.53 | 2.31 | 1.72 | 1.96 | 2.21 | 1.88 |

| Surgeon gender . | Payments ($) . | Individual payment mean ($) . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | 2013 . | 2014 . | 2015 . | 2016 . | 2017 . | 2018 . | 2013-2018 . | . |

| Male | 2272.83 | 4409.40 | 4726.84 | 5134.25 | 3995.04 | 4930.69 | 25,469.05 | 387.68 |

| Female | 963.45 | 1641.99 | 1870.36 | 2220.68 | 2319.97 | 2514.21 | 11,530.67 | 205.85 |

| Male:female payment ratio | 2.36 | 2.69 | 2.53 | 2.31 | 1.72 | 1.96 | 2.21 | 1.88 |

| Surgeon gender . | Payments ($) . | Individual payment mean ($) . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | 2013 . | 2014 . | 2015 . | 2016 . | 2017 . | 2018 . | 2013-2018 . | . |

| Male | 2272.83 | 4409.40 | 4726.84 | 5134.25 | 3995.04 | 4930.69 | 25,469.05 | 387.68 |

| Female | 963.45 | 1641.99 | 1870.36 | 2220.68 | 2319.97 | 2514.21 | 11,530.67 | 205.85 |

| Male:female payment ratio | 2.36 | 2.69 | 2.53 | 2.31 | 1.72 | 1.96 | 2.21 | 1.88 |

| Surgeon gender . | Payments ($) . | Individual payment mean ($) . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | 2013 . | 2014 . | 2015 . | 2016 . | 2017 . | 2018 . | 2013-2018 . | . |

| Male | 2272.83 | 4409.40 | 4726.84 | 5134.25 | 3995.04 | 4930.69 | 25,469.05 | 387.68 |

| Female | 963.45 | 1641.99 | 1870.36 | 2220.68 | 2319.97 | 2514.21 | 11,530.67 | 205.85 |

| Male:female payment ratio | 2.36 | 2.69 | 2.53 | 2.31 | 1.72 | 1.96 | 2.21 | 1.88 |

Of the top 1% of surgeon recipients (N = 39) by dollars received, just 3 (7.7%) of these were women. Four surgeons were disbursed 6-figure amounts (ie, >$100,000) by industry during each year of the 2013 to 2018 period, and all of these individuals were men. Male surgeons made up the vast majority of plastic surgeons receiving 6-figure payments in any one year (34 of 39, 89.5%). The top-earning individual was male; this surgeon amassed $16,400,200.00 over the study period across 300 payments, whereas the top-earning female surgeon earned $414,308.00 across 487 payments.

Over this period, payment trends reveal a steady increase in mean annual sum disbursed to female plastic surgeons, whereas this value remained more stable across the time period for males. The individual female surgeon earned an average of $963.45 in 2013, $1641.99 in 2014, $1870.36 in 2015, $2220.68 in 2016, $4319.97 in 2017, and $2514.21 in 2018.

Discussion

Discrepancies in both amounts and frequencies of fund transfers between companies and plastic surgeons of opposite genders exposes an additional compensation disparity not captured in traditional wage-gap estimations. During the 6 years of recorded Open Payments data to US physicians, male ASPS-affiliated plastic surgeons have received payments from industry on average amounting to greater than twice the payment dollars given to each female surgeon recipient. Over half of all dollars transferred to plastic surgeons by industry went to just 1% of ASPS plastic surgeons receiving payments between 2013 and 2018, with nearly all of these recipients being male. The inequity of payments to male and female ASPS members has slightly declined for 2017 and 2018 as compared to the earlier 2013 to 2016 period. Compared with their male counterparts, women were the recipients of significantly fewer industry payments during 2013 to 2018.

Wages are a form of valuation, customarily a reflection of a laborer’s worth. The greater than 2-fold gender wage gap of industry payments we uncover is significantly more discordant than the previously elucidated 11% compensation gap in plastic surgery declared in the Doximity 2019 Physician Compensation Report.3 Sex-based disparity in corporate payments has been exposed in other fields, such as radiation oncology and ophthalmology and dermatology, and across medicine in general.14-17 Because the financial ramifications of industry preferences has not been extensively studied, the driving forces that may or may not influence these gender discrepancies remain unclear. Mechanisms for this discrepancy could relate to vast differences in the rate of speaker invitations despite equivalent academic qualifications between the genders18 and other services tendered by plastic surgeons for industry. Another possibility is the extension of a self-undervaluing phenomenon found in female general surgeons during salary negotiations19—women may lowball their worth when negotiating with industry partners. There is persistent gender discrepancy between male and female representation on editorial boards and in professional societies in our field, despite growth in female society membership in recent years.20 Women are less likely to be full professors, but the disproportionately large proportion of junior female academics bodes well for progress on this front.21 Nevertheless, it is conceivable that industry contact lists of plastic surgeons for hire could be tied to these statuses and may lag behind for years to come. Because male plastic surgeons historically rise higher in academia,22 they may be a more compelling target for industry.

This analysis expounds upon the work of Ngaage et al10 which focuses on payments to the academic plastic surgeon population in calendar year 2017 exclusively, concluding that although similar portions of males and females receive industry funds, men receive 92% of all disbursed funds. No females received 6-figure disbursements in 2017.23 We similarly find that male plastic surgeons on average receive more than double that received by women. More powerfully, we find that of those surgeons with an annual payment average over the 6 years totaling 6 figures, none are women.

The so-called “leaky pipeline” of females in plastic surgery, where there is a stepwise and drastic decline in the number of women at each successive step of the professional ladder, may be highly intertwined with financial success.1 Fazendin et al1 found industry payment variation by professorial rank among surgeons overall, so drop-off in the proportion of females at higher ends of the career ladder is of consequence in terms of receiving industry funds. When surveyed, the ASPS female cohort was more likely to be unmarried, childless, and to have similar hours and practice profile, while being half as likely to earn an income over $400,000 per year.25

There are several study limitations to bear in mind when interpreting our findings. CMS OPD data points are reliant on the accuracy of their source data entered by biomedical companies under the governmental regulation to report. Individual surgeons do not verify the information in this database. For surgeon sample, we chose the largest and arguably most inclusive professional organization in plastic surgery, purportedly representing 93% of practicing board-certified plastic surgeons in the United States.25 Nevertheless, there may be selection bias involved in sampling this population which excludes nonmember plastic surgeons. There are physicians performing operations who fall under the purview of plastic surgery without being board-certified plastic surgeons, and payments to these individuals are not examined here. Our scope is also limited to General Payments, and we deliberately exclude Research and Ownership payments in order to focus on industry transfers of the most common variety. Scholarly productivity for each surgeon was not investigated here, but it is conceivable that more extensively published surgeons are more visible to industry and may tend to be male. In addition, plastic surgeons of one gender may tend to self-specialize into different branches of the field that attract more or less industry funding (eg, those surgeons performing breast reconstruction benefiting from more dollars from breast implant manufacturers).

Conclusions

As gender-equity efforts regarding the sex distribution of our plastic surgery workforce are on the rise, equal pay for this more diverse labor force will only become a reality when extrasalarial sources of income such as industry payments also reach parity between men and women surgeons. Biomedical corporations have historically paid female plastic surgeons less money and less often than their male counterparts, and this trend holds true for first 6 years of mandatorily reported payment data. Further work will delve into underlying reasons for this discrepancy, and professional societies in plastic surgery should advocate for more equitable industry partnership.

Acknowledgments

The abstract was accepted for presentation at: PSRC 65th Annual Meeting, in May 2020 in Toronto, Ontario, Canada; however the meeting was cancelled.

Disclosures

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

References

ProPublica.

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. About ASPS. PlasticSurgery.org. Published