-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Naveen Virin Goddard, Marc D Pacifico, Gianluca Campiglio, Norman Waterhouse, A Novel Application of the Hemostatic Net in Aesthetic Breast Surgery: A Preliminary Report, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 42, Issue 11, November 2022, Pages NP632–NP644, https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjac058

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Obtaining optimum breast aesthetics can be challenging in secondary aesthetic breast surgery, particularly with poor-quality skin, when downsizing implants, and in cases where patients will not accept additional mastopexy scars. Most techniques described in these cases rely on internal suturing and capsulorrhaphy, which can lack precision in tailoring the skin over the internal pocket.

The aim of this study was to present the authors’ experience with utilizing the hemostatic net to help address a range of challenging breast cases in their practices.

A multicentre retrospective analysis of patients undergoing aesthetic and reconstructive breast surgery between 2019 and 2021 was conducted. A database was established to record patient demographics, indications for surgery, surgical technique, and complications. Following capsulorrhaphy, the hemostatic net was applied in as many rows as required with monofilament sutures and removed 3 to 7 days postoperatively.

Twenty-four women (aged 23-67 years) underwent aesthetic or reconstructive breast surgery with the hemostatic net. This approach optimized stabilization of the inframammary fold and redraping of lax skin or irregularities in the skin envelope. At follow-up review, only 1 instance of the net failing to successfully redrape the skin was seen.

The application of the hemostatic net is an option for patients who might otherwise require mastopexy but refuse to accept the scars. The technique has now been extended to primary cases where implant malposition or skin tailoring issues are anticipated, thus securing its place as a part of the surgical armamentarium.

See the Commentary on this article here.

Redraping excess skin in secondary breast surgery can be challenging, particularly with smooth or nanotextured implants,1,2 in patients with inelastic, poor-quality skin, when downsizing implants, and in cases where the patient refuses to accept the additional mastopexy scars that might otherwise be indicated. In addition, providing additional stability to the inframammary fold (IMF) in these cases is also highly desirable to support the weight of a new prosthesis. This preliminary report describes our early experience with the hemostatic net3 as a means to tailor and reposition the breast skin in these challenging scenarios, particularly in cases where a formal mastopexy might have been indicated.

Apart from mastopexy, the majority of techniques described to accommodate skin laxity and improve breast aesthetics rely on internal suturing4,5 and capsule modification.6,7 Although these approaches can improve the pocket shape and size, and stabilize the implant location, they may be limited in redraping or tailoring the skin or even the internal pocket due to skin dissociation and laxity. Moreover, if total capsulectomy is undertaken due to severe capsular contracture or explantation of macrotextured implants, the capsule will not be available for capsular flaps or suturing work.

In many fields of plastic surgery, quilting sutures have been widely used to secure skin grafts8,9 and abdominoplasty flaps10 to their underlying tissues to close dead space and reduce the likelihood of seroma and hematoma formation. In 2012, Auersvald et al reapplied this principal, utilizing a “hemostatic net” composed of a series of continuous transfixing sutures encompassing the skin and superficial musculoaponeurotic system to prevent hematoma formation and aid skin redistribution in areas dissected during rhytidectomy.3 The use of the hemostatic net has subsequently been described by multiple authors in rhytidectomy,11-14 neck-lift,15-17 gliding brow lift,18 and more recently in gynecomastia surgery,19 not only to successfully close dissected tissue space, but also to redrape and reposition skin laxity in many clinical fields.

Based on our experience with the use of the hemostatic net in facial surgery, we present a multicenter preliminary report where the principles of the hemostatic net are used to address a range of challenging breast cases in our practices. Our early experience with the hemostatic net in challenging secondary cases has been very positive in a range of scenarios, with only 1 instance of the net failing to successfully control lax skin.

METHODS

A multicenter retrospective analysis of patients undergoing aesthetic and reconstructive breast surgery between 2019 and 2021 was conducted. Patients undergoing primary or secondary aesthetic or reconstructive breast procedures in which the hemostatic net was used were included. Patients undergoing gynecomastia surgery were excluded. A database was established to record patient demographics, indications, surgical technique, results, and complications.

The size and type of suture used for the hemostatic net, the duration of the net sutures in situ, and the length of follow-up was analyzed for all patients. Particular attention was paid to the shape control achieved in the lateral and inferior poles. All patients were followed up for at least 3 months (mean, 12.9 months). Although patient satisfaction was not formally evaluated with a validated scoring system, informal patient satisfaction feedback direct to the surgeon and via invited reviews was collated. This study follows the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and all patients provided written informed consent.

Surgical Technique

Surgical planning was customized to each patient and clinical scenario, but some principles were established in common to all. Patients were marked preoperatively either standing or sitting up straight. Their existing breast footprint (as delineated by their implants or natural breast borders) were marked and the ideal aesthetic breast lines were determined by displacement of the breast and/or implant. This included medial and lateral displacement as warranted, as well as cranial displacement. In many patients, additional analysis and marking when supine was also beneficial.

For most cases, implant removal and initial capsule work (capsulectomy, capsulorrhaphy, etc) was undertaken first. A temporary sizing implant was inserted to act as a guide for further maneuvers. Following the preoperatively planned ideal breast aesthetic lines, and assisted by the temporary sizer, rows of external hemostatic net sutures were inserted, most commonly 3/0 Ethilon (Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, NJ) or either 2/0 or 4/0 Monocryl (Ethicon) or 3/0 Prolene (Ethicon), as continuous sutures, with the aid of an assistant maintaining the breast in its ideal position (Figure 1). This provided an external scaffold or framework around which the breast and implant could be stabilized.

(A) Intraoperative clinical photographs of a 66-year-old female patient who presented with unilateral intracapsular implant rupture and underwent exchange and downsizing of her 425-g McGhan tall height anatomic implants (Allergan, Inc., Dublin, Ireland) for 255-cc Mentor CPG312 implants (Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, NJ). Preoperative markings were used to outline the preoperative footprint of the implant (inferior marking) compared to the ideal aesthetic breast lines (superior marking); the markings subsequently acted as an intraoperative guide when placing the hemostatic net. (B) The hemostatic net is seen in situ providing an external framework that stabilizes the new implant over the ideal breast footprint. (C) One month postoperative clinical photographs demonstrating the lateral and caudal skin redraping that was achieved with the net.

Further internal suturing was subsequently undertaken as required, including IMF stabilizing sutures and lateral pocket tailoring. A predetermined smooth or nanotextured implant (as determined from tissue-based planning20) was then used according to the requirements of the individual patient, and a 3-layer closure was performed, usually with 3/0 and/or 4/0 Monocryl. A nonadhesive dressing (eg, Mepitel; Mölnlycke Health Care, Gothenburg, Sweden) was applied over the hemostatic net to avoid discomfort from a postsurgical bra. The hemostatic net sutures were removed 3 to 7 days after surgery. The varied length of time the sutures were maintained reflected the iterative journey we have been on to determine the optimum retention time for the sutures. As we describe in more detail below, in the Discussion, part of the decision is related to the subjective analysis of the patient’s tissues and skin.

RESULTS

Twenty-four female patients (age range, 23-67 years; mean, 40 years) received the hemostatic net during breast surgery in the authors’ private practices (total, 48 breasts): 4 patients received the hemostatic net after mastopexy, 4 after revisional surgery for malpositioned implants, 4 after bilateral breast augmentation, 3 during aesthetic surgery to correct the areola in tuberous breasts, 3 after augmentation mastopexy, and 2 after reverse abdominoplasty. Four further patients received the net after either IMF symmetrization, symmastia, implant failure, or latissimus dorsi breast reconstruction, respectively. The majority of hemostatic nets were composed of 2/0 Monocryl (n = 26 breasts); however, 3/0 Ethilon (n = 12 breasts), 4/0 Monocryl (n = 8 breasts), and 3/0 Prolene (n = 2 breasts) were also used. The net was left in situ for either 3 (n = 6 breasts), 4 (n = 32 breasts), or 7 days (10 breasts) before being removed.

Application of wound dressings included an initial protective layer of gauze over the net sutures to prevent rubbing, and then a surgical bra over the gauze. At 1 to 2 weeks after surgery, patients were placed into an underwired bra early to provide additional external support and were instructed that the wires of the bra should sit accurately in the breast crease to help to ensure stability. In some cases, Micropore Tape (3M, St Paul, MN) was used to shape the skin and reduce the swelling after the hemostatic net was removed.

Length of follow-up varied from 3 months to 2 years (mean, 12.9 months). Although hyperpigmented (n = 2 patients) and hypopigmented (n = 1 patient) suture marks were identified in 3 patients initially, only 1 patient experienced mild hypopigmented suture marks at 1-year follow-up.

Overall, the only long-term complications we have observed were the presence of small hypopigmented scars in the 1 patient at 12 months, and failure of the net to accurately control the position of the IMF in 1 further patient. The patient with the hypopigmented scars was young (in her 20s) and had thick skin, and the sutures were left in for 1 week. We speculate that had the sutures been removed sooner, this complication might not have arisen. In the second patient, the loss of IMF control occurred despite the hemostatic net, although this may have been in part due to the patient’s refusal to downsize her implants.

We acknowledge from the outset that in this preliminary report we are presenting our experience with this novel technique to our colleagues, rather than performing a detailed scientific analysis. Further reporting and analysis are planned once longer-term follow-up is achieved and greater numbers can be included.

Details of patient demographics and surgical procedures can be found in Table 1. Further details in Table 1 include suture material used, time the net was left in situ, length of follow-up, results, and complications.

Demographics, Surgical Indications, and Surgical Techniques Used in Patients Included in this Series, Including Length of Follow-up, Results, and Complications

| Age (years) . | Gender . | Surgical procedure . | Indication for surgery . | Suture used for hemostatic net (material and size) . | Time suture left in situ (days) . | Length of follow-up (months) . | Results . | Complications . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | Female | Revision breast reduction/mastopexy and augmentation | Bottomed-out breasts: IMF malpositioned caudally | 3/0 Ethilon | 7 | 12 | Well-proportioned, larger breasts with stable improvement in the IMF position | Hypopigmented net suture marks at 1-year follow-up |

| 61 | Female | Breast implant exchange and change of plane | Implant malposition: waterfall effect | 3/0 Ethilon | 7 | 6 | Unable to control shape of lateral curvature of breast internally. Excellent shape control achieved with net | None |

| 24 | Female | Revision breast implant surgery | Implant malposition | 3/0 Ethilon | 7 | 6 | Improvement in implant position and overall breast aesthetics | None |

| 66 | Female | Implant revision | Implant malposition: overly large implants | 3/0 Ethilon | 7 | 3 | 425-cc McGhan implants (Allergan, Irvine, CA) were replaced with 255-cc Mentor implants (Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, NJ). Good shape control achieved with net | None |

| 30 | Female | Implant revision | Implant malposition: bottomed-out implants, waterfall effect | 3/0 Ethilon | 7 | 9 | Good shape control achieved | None |

| 24 | Female | Reverse abdominoplasty | Excess fat and skin in the upper abdomen | 3/0 Prolene | 3 | 7 | Excess fat and skin were excised, the IMF was successfully stabilized with the net without any tension across the fold | None |

| 46 | Female | Reverse abdominoplasty | Excess fat and skin in the upper abdomen | 3/0 Ethilon | 3 | 3 | Upper abdominal skin laxity corrected, glandular ptosis improved, IMF stabilized | None |

| 38 | Female | Mastopexy | Breast ptosis | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 20 | Improvement of breast ptosis | None |

| 41 | Female | Mastopexy | Breast ptosis | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 19 | Improvement of breast ptosis | None |

| 44 | Female | Mastopexy | Breast ptosis | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 24 | Improvement of breast ptosis | None |

| 41 | Female | Mastopexy | Symmastia | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 20 | Improvement in medial border of breast | None |

| 36 | Female | IMF symmetrization | IMF asymmetry | 4/0 Monocryl | 3 | 26 | Loss of IMF control occurred despite the net | Relapse of IMF asymmetry |

| 54 | Female | Implant exchange | Symmastia | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 20 | Increased IMF stability, improved cleavage symmetry and medial and inferior breast contour | None |

| 45 | Female | Implant exchange | Implant failure | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 22 | Repositioning of implant in optimum position, restored overall breast aesthetic | None |

| 23 | Female | Areola adjustment in tubular breasts | Puffy areola | 4/0 Monocryl | 4 | 23 | Improvement in areola aesthetics | None |

| 27 | Female | Areola adjustment in tubular breasts | Nipple pointing down | 4/0 Monocryl | 4 | 16 | Improvement in areola aesthetics and nipple projection | None |

| 24 | Female | Areola adjustment in tubular breasts | Nipple pointing down | 4/0 Monocryl | 4 | 11 | Improvement in areola aesthetics and nipple projection | None |

| 35 | Female | Breast reconstruction | Latissimus dorsi flap | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 11 | Restoration in breast volume and improvement in breast aesthetic | Temporary hyperpigmented net suture marks |

| 48 | Female | Revision augmentation mastopexy | Implant displacement | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 3 | Repositioning of breast implant into optimum position, stable IMF | None |

| 67 | Female | Revision augmentation mastopexy | Implant displacement | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 3 | Repositioning of breast implant into optimum position, stable IMF | None |

| 31 | Female | Breast augmentation | Implant displacement | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 3.5 | Repositioning of implant with good skin redraping achieved | None |

| 44 | Female | Breast augmentation | Implant displacement | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 3.5 | Repositioning of implant with good skin redraping achieved | None |

| 33 | Female | Breast augmentation | Augmentation | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 16 | Larger, fuller, well-proportioned breasts | None |

| 37 | Female | Breast augmentation | Augmentation | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 22 | Larger, fuller, well-proportioned breasts | Temporary hyperpigmented net suture marks |

| Age (years) . | Gender . | Surgical procedure . | Indication for surgery . | Suture used for hemostatic net (material and size) . | Time suture left in situ (days) . | Length of follow-up (months) . | Results . | Complications . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | Female | Revision breast reduction/mastopexy and augmentation | Bottomed-out breasts: IMF malpositioned caudally | 3/0 Ethilon | 7 | 12 | Well-proportioned, larger breasts with stable improvement in the IMF position | Hypopigmented net suture marks at 1-year follow-up |

| 61 | Female | Breast implant exchange and change of plane | Implant malposition: waterfall effect | 3/0 Ethilon | 7 | 6 | Unable to control shape of lateral curvature of breast internally. Excellent shape control achieved with net | None |

| 24 | Female | Revision breast implant surgery | Implant malposition | 3/0 Ethilon | 7 | 6 | Improvement in implant position and overall breast aesthetics | None |

| 66 | Female | Implant revision | Implant malposition: overly large implants | 3/0 Ethilon | 7 | 3 | 425-cc McGhan implants (Allergan, Irvine, CA) were replaced with 255-cc Mentor implants (Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, NJ). Good shape control achieved with net | None |

| 30 | Female | Implant revision | Implant malposition: bottomed-out implants, waterfall effect | 3/0 Ethilon | 7 | 9 | Good shape control achieved | None |

| 24 | Female | Reverse abdominoplasty | Excess fat and skin in the upper abdomen | 3/0 Prolene | 3 | 7 | Excess fat and skin were excised, the IMF was successfully stabilized with the net without any tension across the fold | None |

| 46 | Female | Reverse abdominoplasty | Excess fat and skin in the upper abdomen | 3/0 Ethilon | 3 | 3 | Upper abdominal skin laxity corrected, glandular ptosis improved, IMF stabilized | None |

| 38 | Female | Mastopexy | Breast ptosis | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 20 | Improvement of breast ptosis | None |

| 41 | Female | Mastopexy | Breast ptosis | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 19 | Improvement of breast ptosis | None |

| 44 | Female | Mastopexy | Breast ptosis | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 24 | Improvement of breast ptosis | None |

| 41 | Female | Mastopexy | Symmastia | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 20 | Improvement in medial border of breast | None |

| 36 | Female | IMF symmetrization | IMF asymmetry | 4/0 Monocryl | 3 | 26 | Loss of IMF control occurred despite the net | Relapse of IMF asymmetry |

| 54 | Female | Implant exchange | Symmastia | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 20 | Increased IMF stability, improved cleavage symmetry and medial and inferior breast contour | None |

| 45 | Female | Implant exchange | Implant failure | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 22 | Repositioning of implant in optimum position, restored overall breast aesthetic | None |

| 23 | Female | Areola adjustment in tubular breasts | Puffy areola | 4/0 Monocryl | 4 | 23 | Improvement in areola aesthetics | None |

| 27 | Female | Areola adjustment in tubular breasts | Nipple pointing down | 4/0 Monocryl | 4 | 16 | Improvement in areola aesthetics and nipple projection | None |

| 24 | Female | Areola adjustment in tubular breasts | Nipple pointing down | 4/0 Monocryl | 4 | 11 | Improvement in areola aesthetics and nipple projection | None |

| 35 | Female | Breast reconstruction | Latissimus dorsi flap | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 11 | Restoration in breast volume and improvement in breast aesthetic | Temporary hyperpigmented net suture marks |

| 48 | Female | Revision augmentation mastopexy | Implant displacement | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 3 | Repositioning of breast implant into optimum position, stable IMF | None |

| 67 | Female | Revision augmentation mastopexy | Implant displacement | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 3 | Repositioning of breast implant into optimum position, stable IMF | None |

| 31 | Female | Breast augmentation | Implant displacement | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 3.5 | Repositioning of implant with good skin redraping achieved | None |

| 44 | Female | Breast augmentation | Implant displacement | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 3.5 | Repositioning of implant with good skin redraping achieved | None |

| 33 | Female | Breast augmentation | Augmentation | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 16 | Larger, fuller, well-proportioned breasts | None |

| 37 | Female | Breast augmentation | Augmentation | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 22 | Larger, fuller, well-proportioned breasts | Temporary hyperpigmented net suture marks |

IMF, inframammary fold.

Demographics, Surgical Indications, and Surgical Techniques Used in Patients Included in this Series, Including Length of Follow-up, Results, and Complications

| Age (years) . | Gender . | Surgical procedure . | Indication for surgery . | Suture used for hemostatic net (material and size) . | Time suture left in situ (days) . | Length of follow-up (months) . | Results . | Complications . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | Female | Revision breast reduction/mastopexy and augmentation | Bottomed-out breasts: IMF malpositioned caudally | 3/0 Ethilon | 7 | 12 | Well-proportioned, larger breasts with stable improvement in the IMF position | Hypopigmented net suture marks at 1-year follow-up |

| 61 | Female | Breast implant exchange and change of plane | Implant malposition: waterfall effect | 3/0 Ethilon | 7 | 6 | Unable to control shape of lateral curvature of breast internally. Excellent shape control achieved with net | None |

| 24 | Female | Revision breast implant surgery | Implant malposition | 3/0 Ethilon | 7 | 6 | Improvement in implant position and overall breast aesthetics | None |

| 66 | Female | Implant revision | Implant malposition: overly large implants | 3/0 Ethilon | 7 | 3 | 425-cc McGhan implants (Allergan, Irvine, CA) were replaced with 255-cc Mentor implants (Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, NJ). Good shape control achieved with net | None |

| 30 | Female | Implant revision | Implant malposition: bottomed-out implants, waterfall effect | 3/0 Ethilon | 7 | 9 | Good shape control achieved | None |

| 24 | Female | Reverse abdominoplasty | Excess fat and skin in the upper abdomen | 3/0 Prolene | 3 | 7 | Excess fat and skin were excised, the IMF was successfully stabilized with the net without any tension across the fold | None |

| 46 | Female | Reverse abdominoplasty | Excess fat and skin in the upper abdomen | 3/0 Ethilon | 3 | 3 | Upper abdominal skin laxity corrected, glandular ptosis improved, IMF stabilized | None |

| 38 | Female | Mastopexy | Breast ptosis | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 20 | Improvement of breast ptosis | None |

| 41 | Female | Mastopexy | Breast ptosis | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 19 | Improvement of breast ptosis | None |

| 44 | Female | Mastopexy | Breast ptosis | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 24 | Improvement of breast ptosis | None |

| 41 | Female | Mastopexy | Symmastia | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 20 | Improvement in medial border of breast | None |

| 36 | Female | IMF symmetrization | IMF asymmetry | 4/0 Monocryl | 3 | 26 | Loss of IMF control occurred despite the net | Relapse of IMF asymmetry |

| 54 | Female | Implant exchange | Symmastia | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 20 | Increased IMF stability, improved cleavage symmetry and medial and inferior breast contour | None |

| 45 | Female | Implant exchange | Implant failure | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 22 | Repositioning of implant in optimum position, restored overall breast aesthetic | None |

| 23 | Female | Areola adjustment in tubular breasts | Puffy areola | 4/0 Monocryl | 4 | 23 | Improvement in areola aesthetics | None |

| 27 | Female | Areola adjustment in tubular breasts | Nipple pointing down | 4/0 Monocryl | 4 | 16 | Improvement in areola aesthetics and nipple projection | None |

| 24 | Female | Areola adjustment in tubular breasts | Nipple pointing down | 4/0 Monocryl | 4 | 11 | Improvement in areola aesthetics and nipple projection | None |

| 35 | Female | Breast reconstruction | Latissimus dorsi flap | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 11 | Restoration in breast volume and improvement in breast aesthetic | Temporary hyperpigmented net suture marks |

| 48 | Female | Revision augmentation mastopexy | Implant displacement | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 3 | Repositioning of breast implant into optimum position, stable IMF | None |

| 67 | Female | Revision augmentation mastopexy | Implant displacement | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 3 | Repositioning of breast implant into optimum position, stable IMF | None |

| 31 | Female | Breast augmentation | Implant displacement | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 3.5 | Repositioning of implant with good skin redraping achieved | None |

| 44 | Female | Breast augmentation | Implant displacement | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 3.5 | Repositioning of implant with good skin redraping achieved | None |

| 33 | Female | Breast augmentation | Augmentation | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 16 | Larger, fuller, well-proportioned breasts | None |

| 37 | Female | Breast augmentation | Augmentation | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 22 | Larger, fuller, well-proportioned breasts | Temporary hyperpigmented net suture marks |

| Age (years) . | Gender . | Surgical procedure . | Indication for surgery . | Suture used for hemostatic net (material and size) . | Time suture left in situ (days) . | Length of follow-up (months) . | Results . | Complications . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | Female | Revision breast reduction/mastopexy and augmentation | Bottomed-out breasts: IMF malpositioned caudally | 3/0 Ethilon | 7 | 12 | Well-proportioned, larger breasts with stable improvement in the IMF position | Hypopigmented net suture marks at 1-year follow-up |

| 61 | Female | Breast implant exchange and change of plane | Implant malposition: waterfall effect | 3/0 Ethilon | 7 | 6 | Unable to control shape of lateral curvature of breast internally. Excellent shape control achieved with net | None |

| 24 | Female | Revision breast implant surgery | Implant malposition | 3/0 Ethilon | 7 | 6 | Improvement in implant position and overall breast aesthetics | None |

| 66 | Female | Implant revision | Implant malposition: overly large implants | 3/0 Ethilon | 7 | 3 | 425-cc McGhan implants (Allergan, Irvine, CA) were replaced with 255-cc Mentor implants (Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, NJ). Good shape control achieved with net | None |

| 30 | Female | Implant revision | Implant malposition: bottomed-out implants, waterfall effect | 3/0 Ethilon | 7 | 9 | Good shape control achieved | None |

| 24 | Female | Reverse abdominoplasty | Excess fat and skin in the upper abdomen | 3/0 Prolene | 3 | 7 | Excess fat and skin were excised, the IMF was successfully stabilized with the net without any tension across the fold | None |

| 46 | Female | Reverse abdominoplasty | Excess fat and skin in the upper abdomen | 3/0 Ethilon | 3 | 3 | Upper abdominal skin laxity corrected, glandular ptosis improved, IMF stabilized | None |

| 38 | Female | Mastopexy | Breast ptosis | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 20 | Improvement of breast ptosis | None |

| 41 | Female | Mastopexy | Breast ptosis | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 19 | Improvement of breast ptosis | None |

| 44 | Female | Mastopexy | Breast ptosis | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 24 | Improvement of breast ptosis | None |

| 41 | Female | Mastopexy | Symmastia | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 20 | Improvement in medial border of breast | None |

| 36 | Female | IMF symmetrization | IMF asymmetry | 4/0 Monocryl | 3 | 26 | Loss of IMF control occurred despite the net | Relapse of IMF asymmetry |

| 54 | Female | Implant exchange | Symmastia | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 20 | Increased IMF stability, improved cleavage symmetry and medial and inferior breast contour | None |

| 45 | Female | Implant exchange | Implant failure | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 22 | Repositioning of implant in optimum position, restored overall breast aesthetic | None |

| 23 | Female | Areola adjustment in tubular breasts | Puffy areola | 4/0 Monocryl | 4 | 23 | Improvement in areola aesthetics | None |

| 27 | Female | Areola adjustment in tubular breasts | Nipple pointing down | 4/0 Monocryl | 4 | 16 | Improvement in areola aesthetics and nipple projection | None |

| 24 | Female | Areola adjustment in tubular breasts | Nipple pointing down | 4/0 Monocryl | 4 | 11 | Improvement in areola aesthetics and nipple projection | None |

| 35 | Female | Breast reconstruction | Latissimus dorsi flap | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 11 | Restoration in breast volume and improvement in breast aesthetic | Temporary hyperpigmented net suture marks |

| 48 | Female | Revision augmentation mastopexy | Implant displacement | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 3 | Repositioning of breast implant into optimum position, stable IMF | None |

| 67 | Female | Revision augmentation mastopexy | Implant displacement | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 3 | Repositioning of breast implant into optimum position, stable IMF | None |

| 31 | Female | Breast augmentation | Implant displacement | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 3.5 | Repositioning of implant with good skin redraping achieved | None |

| 44 | Female | Breast augmentation | Implant displacement | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 3.5 | Repositioning of implant with good skin redraping achieved | None |

| 33 | Female | Breast augmentation | Augmentation | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 16 | Larger, fuller, well-proportioned breasts | None |

| 37 | Female | Breast augmentation | Augmentation | 2/0 Monocryl | 4 | 22 | Larger, fuller, well-proportioned breasts | Temporary hyperpigmented net suture marks |

IMF, inframammary fold.

Case Reports

Case 1

A 54-year-old female patient (G1 P1) presented with unilateral right-sided implant failure (Allergan Inspira TSF 345, Allergan, Irvine, CA), symmastia, and a bilaterally irregular IMF, most evident on the medial aspect of the right breast (Figure 2). The patient hoped to achieve bilateral breast symmetry without decreasing breast size.

Preoperative clinical photographs of a 54-year-old female patient who presented with right-sided implant failure, symmastia, and a bilaterally irregular inframammary fold: (A) left oblique view, (B) frontal view, and (C) right oblique view. The patient’s intraoperative photographs can be seen in Figures 3 and 4.

A periareolar approach was used, with no skin caudal to the areola excised. First, a total capsulectomy was undertaken to clear any residual silicone from the breast pocket and reduce the likelihood of subsequent siliconomas arising from an infiltrated capsule. The hemostatic net was then applied for 4 days with 2/0 Monocryl to provide a reinforced external framework to the medial, inferior, and lateral aspects of each breast pocket (Figure 3). Internal 2/0 Vicryl sutures (Ethicon) were then used medially to address the irregular IMF, and to shape the breast pocket laterally and inferiorly. Although we considered the option, the hemostatic net could not be applied below the areola because it needs strong underlying tissues to exert its reshaping effect.

Intraoperative photographs of the 54-year-old female patient seen in Figure 2. The patient underwent capsulectomy and reinforcement of the ideal breast footprint with net sutures, before reshaping of the breast pocket with internal sutures and replacement of her breast implants bilaterally. The hemostatic net is seen in situ over the medial, inferior, and lateral aspects of the right breast pocket prior to implant insertion, with the commencement of the net placement on the left side being demonstrated.

The combination of internal and external sutures in this case allowed optimal tailoring of both the internal pocket and the external breast shape, respectively, thus allowing the surgeon to symmetrize both the medial aspect of the breast and the IMF, as well as preserving the breast size desired by the patient with smooth round 450-cc Mentor implants (Ethicon) (Figure 4). No long-term postoperative complications, including hyperpigmented marks from the net sutures, were seen. Pre- and postoperative clinical photographs (Figure 5) demonstrate the improvement in overall breast aesthetics achieved, particularly with respect to the medial and inferior contour of the breast, the cleavage symmetry, and the stable IMF.

Final on-table intraoperative photographs of the 54-year-old female patient seen in Figure 2. The new implants and hemostatic net are seen in situ at the end of the surgery.

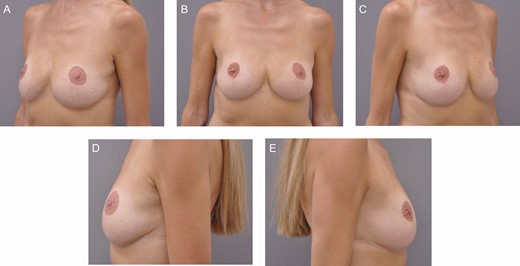

Preoperative and 1-year postoperative clinical photographs of the 54-year-old female patient seen in Figure 2. (A, B) Frontal view, with a significant and stable improvement in breast aesthetics, with an aesthetic reconstruction of both the inframammary folds and correction of the symmastia, with restoration of cleavage lines. Improvement in breast aesthetics (C, D) from the right oblique view, and (E, F) from the left oblique view.

Although a mild asymmetry is still present, the preoperative difference between the 2 breasts has been improved, especially regarding the roundness and smoothness of the right inferior pole (Figure 6). The right breast was elevated during the surgery; Figure 4 demonstrates the right IMF being intentionally overcorrected, elevating it in a more superior position compared with the contralateral side.

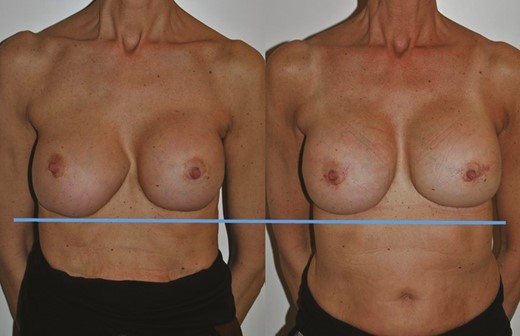

Preoperative (left) and 1-year postoperative (right) clinical photographs of the 54-year-old female patient seen in Figure 2. Although a mild asymmetry is still present, the preoperative difference between the 2 breasts has been improved, especially regarding the roundness and smoothness of the right inferior pole. The horizontal blue line demonstrates the elevation of the right inframammary fold achieved by the intentional overcorrection demonstrated in Figure 4.

Case 2

A 46-year-old female presented having previously undergone abdominoplasty with additional vibration amplification of sound energy at resonance (VASER) liposuction and BodyTite (InMode, Irvine, CA) procedures for skin tightening. The patient was left with excess skin laxity in the upper abdomen. In addition, the patient had previously undergone both breast augmentation mammaplasty as well as breast reduction mammaplasty and now presented with large breasts with glandular ptosis and upward orientation of the nipple-areola complexes (Figure 7). The nipple to IMF distance was 12 cm on the right and 13 cm on the left. As she had already had the transverse scars of a reduction mammaplasty, it was elected to use a reverse abdominoplasty to remove the excess skin in the upper abdomen, stabilize the IMF, and correct her glandular ptosis. A traditional abdominoplasty was considered inappropriate due to tight lower abdominal skin, an elevated low abdominal scar, and tension in skin over the mons.

Preoperative clinical photograph of a 46-year-old female patient who underwent a reverse abdominoplasty after being left with excess skin in the upper abdomen after a previous lower abdominoplasty with additional VASER liposuction and BodyTite (InMode, Irvine, CA) treatment.

Intraoperatively the excess skin was removed from the upper abdomen and advanced over the ribs. The excision was designed to dovetail into the previous breast reduction scars (Figure 8). The implant capsule was preserved in order not to expose the implants. The upper abdominal flap was undermined, elevated, contoured, and advanced into the new IMF. The wounds were closed in multiple layers and then 3/0 Ethilon hemostatic net sutures were used to secure the flap in position and stabilize the IMFs (Figure 9). The hemostatic net sutures were removed 3 days postoperatively. Three months postoperatively, the glandular ptosis had improved, the IMF had stabilized, and the upper abdominal skin laxity was corrected (Figure 10).

Intraoperative clinical photographs of the 46-year-old female patient in Figure 7. The upper abdominal flap was undermined, elevated, contoured, and advanced into the new inframammary fold.

Intraoperative clinical photographs of the 46-year-old female patient in Figure 7. The hemostatic net is demonstrated stabilizing the inframammary folds and securing the upper abdominal flap in situ fixed to the underlying deep fascia.

A 3-month postoperative result of the 46-year-old female patient in Figure 7. At this early follow-up a good improvement of the upper abdominal skin laxity is demonstrated with additional benefits to the glandular ptosis of the breasts evident in the preoperative photographs (Figure 7). The hemostatic net has provided a stable base and support for the reverse abdominoplasty.

Case 3

A 40-year-old (P1 G0) patient who had previously undergone reduction mammaplasty surgery 10 years previously with pre-existing symmastia presented after becoming aware of bottoming out of her breasts, resulting in overly long lower poles and high-riding nipples (Figure 11). In addition to addressing her suboptimal breast aesthetics, the patient desired a breast augmentation to address concerns about upper pole fullness and an overall desire for increased volume.

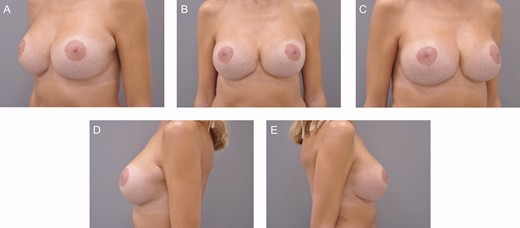

Preoperative clinical photographs of a 40-year-old female patient who presented with a combination of high-riding nipples and pseudoptosis having previously undergone a reduction mammaplasty elsewhere: (A) left oblique view, (B) frontal view, (C) right oblique view, (D) left lateral view, and (E) right lateral view. She sought an increase in volume, particularly in the upper poles, as well as correction of the suboptimal aesthetics of her breast. This patient underwent a lower pole mastopexy augmentation combined with the use of the hemostatic net to stabilize and recontour the lower pole of the breast, raise and support the inframmamary crease, and in effect, undergo a reverse abdominoplasty to lift the thoraco-epigastric skin more cranially. (See main text for further details.).

After discussing the patient’s concerns regarding pseudoptosis, a plan was made for a combination procedure of lower pole mastopexy augmentation6 combined with the use of the hemostatic net to lift and support the neo-inframammary fold, as well as effectively performing a reverse abdominoplasty. An anatomic implant (Nagor 365-cc XF3-365; Nagor Ltd, Glasgow, UK) was chosen due to the patient’s breast morphology and lack of upper pole soft tissue cover.

Intraoperatively the previous IMF scars were excised and the skin inferior to the scar was undermined caudally to dissect out the bottomed-out gland, before continuing cranially, initially in a subglandular plane. As the breasts were so low on the chest wall the initial plane of dissection was over the rectus abdominis (Video 1).

Once the pectoralis major was reached, a dual-plane pocket was created for the implant and a temporary sizer was used. The IMF was recreated and relocated with 3/0 polydioxanone (Ethicon) sutures, and then 3/0 Ethilon hemostatic net sutures were used in 2 rows to stabilize the IMF position and to obliterate the undermined caudal dead space. This effectively provided a stable base for the newly repositioned IMF, as well as being a reverse abdominoplasty (Video 2).

The lower pole breast tissue was then used as a superiorly based flap hammock (lower pole mastopexy augmentation) to further support the implant (3/0 polydioxanone) (Video 3). The implant was inserted, and this acted as a fulcrum over which the breast was then de-rotated caudally on closure, which addressed the previous suboptimal breast proportions and lowered the relative position of the nipple on the breast mound (Video 4).

The patient recovered uneventfully, and the hemostatic net sutures were removed at 1 week postoperatively. The patient’s goals of fuller, larger breasts were met, and her breast proportions improved. Most noticeable was the stable improvement in the position of the IMF that the hemostatic net afforded. Results 1 year postoperatively are shown (Figure 12). Evidence of mild hypopigmentation resulting from the net was seen at 1-year follow-up (Figure 13).

One-year postoperative clinical photographs of the 40-year-old female patient seen in Figure 11: (A) left oblique view, (B) frontal view, (C) right oblique view, (D) left lateral view, and (E) right lateral view. Much improved overall proportions of her breasts can be appreciated with the nipple-areola complex more appropriately sited on the breast mound. Despite a relatively large implant being placed into an uncertain soft tissue environment, the hemostatic net has provided stability to the IMF and cranial advancement of the thoraco-epigastric skin.

Close-up detail of the 40-year-old female patient seen in Figure 11. Very small pale suture marks are evident in the thoraco-epigastric skin. The authors speculate that this might be due to a combination of the length of time the sutures remained in situ (1 week) combined with her subjectively assessed good-quality thick skin.

DISCUSSION

In this preliminary report we present further indications for the hemostatic net described by Auersvald et al3 for application in challenging breast surgery cases. In our practices, the hemostatic net was initially used in patients with malpositioned implants who were reluctant to accept further mastopexy scars. In these cases (unlike previously described capsular flaps6,7 and internal mastopexy procedures4,5 that focus on the internal aspects of breast reshaping) the hemostatic net allowed the skin overlying the breast pocket to be precisely tailored.

Once the skin was redraped over the breast pocket it allowed more precise aesthetic reconstruction of the breast footprint and 3-dimensional aesthetics, facilitating a decrease in implant size, positioning the IMF, and draping redundant lateral breast skin. We have also demonstrated that the net can be used when capsulectomy is performed following implant failure or in cases of substitution of macrotextured prostheses, as well as in situations aiming to prevent excess tension on the IMF when cranial relocation of thoraco-epigastric skin is required.

Inevitably there has been a learning curve over the period of the study, which has allowed us to develop technical refinements as well as suggestions on the length of time the hemostatic net is retained before suture removal. We acknowledge that despite being able to control the breast shape well with this approach, it is not a substitute for a formal mastopexy, which would often be our conventional approach in some of these situations. However, in cases in which it is hard to justify the additional scars of a mastopexy, and for patients who want to avoid a mastopexy, the hemostatic net offers an option for controlling the skin in a way that was hitherto impossible.

The hemostatic net has offered an opportunity to tailor the skin in cases where our patients refused the additional scarring of a mastopexy (often contrary to our recommended advice), rendering us unable to perform any further skin excision or skin tailoring techniques to reshape the breast and the skin envelope. As illustrated in the intraoperative series (Figure 1), the net can demonstrably recontour and redrape lax skin that is not adhering to the desired contour around the breast and implant. We are not suggesting the net is a replacement or an equal alternative to mastopexy, but it is a very useful tool in our armamentarium for dealing with lax skin that requires redraping and stabilization when we cannot undertake a mastopexy.

As well as stabilizing the breast footprint in its ideal position prior to insertion of internal sutures, external net sutures can also reinforce internal sutures, thus efficiently redraping the skin around the ideal breast footprint while also reducing the risk of early rupture of internal sutures and relapse. This reinforcement is particularly useful when dealing with large or submuscular implants.

It is the responsibility of the surgeon to openly discuss the concept of the hemostatic net and its limitations with patients as part of the preoperative consent process. The limitations that we have noted include a degree of unpredictability related to the power of the skin redraping, inevitably related to the thickness and quality of the patient’s skin. We have noted a possible higher risk of long-term suture marks from the hemostatic net in younger and thicker skin, as illustrated in our third case report. Patients with older, thinner, and less elastic skin appear less likely to develop these marks. We would urge caution in maintaining the hemostatic net in place for any prolonged period in pigmented skin due to the risk of creating hypo- or hyperpigmented scars. Although application of the net does marginally increase operating time and can cause some temporary increased discomfort for the patient, on balance we feel that these small limitations are outweighed by the benefits the net provides.

What has been positively observed is that even in those patients with relatively aged and thin skin, the net appears to sustain the redraped skin in its desired position, particularly around the lateral aspect of the breast—an area that is notoriously challenging to control without mastopexy approaches. Each of the 3 authors have independently evolved a similar approach during their individual experience of utilizing the hemostatic net for secondary breast implant surgery. We advocate preoperatively marking the displaced implant with the patient standing, and marking any lateralization of the implant that occurs when the patient is supine. The ideal position of the device is then marked on the patient after displacing the implant as required, in order to provide a map of where the hemostatic net will be required during surgery.

In malpositioned secondary breast implant cases, decisions regarding management of the implant capsule are fundamental. We do not advocate a particular approach to the capsule, as we have not observed any benefit or problem with one capsule technique over another with respect to our use of the hemostatic net—the net acting as a synergistic tool in each case in which it was implemented. In our series we have included patients who have had total capsulectomies, capsular flaps, and various capsulorrhaphy techniques.21,22 However, in the absence of a pathological Baker Grade III or IV capsular contracture,23 internal capsular flaps might confer further benefits in supporting the positioning of an implant in addition to the hemostatic net.

In non-malpositioned implant cases in patients who are subjectively judged to have poor tissue quality by their clinician, a supportive capsule tailored to an appropriate capsular flap can also provide extra support to an implant. However, if the capsule is particularly weak or requires removal, we advocate that the hemostatic net be used as an adjunct to reinforce the internal pocket, thus reducing the need for internal meshes and their potential associated complications.24 This raises the discussion point regarding the alternative use of absorbable (or other) meshes. However, meshes offer internal support only. Particularly in inelastic thin skin, such as in secondary or aged cases, they do not control the behavior of the breast skin envelope. External hemostatic net sutures can certainly be used in conjunction with the mesh, but we do not feel a mesh is a “like-for-like” alternative. Furthermore, use of a mesh introduces further potential complications and is therefore desirable to avoid when possible.

We have found that the external net sutures stabilize the footprint of the breast by fixing the surrounding mobile soft tissue and skin. Furthermore, they allow the surgeon to alter the footprint of the breast, either by incorporating caudal or lateral chest wall skin into the breast, or conversely, moving some of the previous breast skin onto the chest wall.

Internal capsular or crease reinforcement sutures and external sutures are complementary—the internal sutures can help tailor the internal pocket, while the external sutures can tailor the surrounding skin. However, as alluded to above, in secondary cases, particularly in those with lax skin, the internal sutures are frequently insufficient to adequately impart the desired changes on the skin, as there is, in a sense, a delamination between the different tissue planes. Therefore, the additional external net sutures provide control for this situation.

One question that arises is the order of insertion of sutures—should the net sutures be applied first, to provide a stable external framework to outline and position the breast footprint, or should the net sutures only be added if internal sutures are determined to be inadequate to reshape the breast? We have had different experiences with this, and in some cases, we have found that initial net application is beneficial. Application of the net before any internal work supports the breast in its ideal position, permitting the best chance of achieving skin redraping and shape control, which can be difficult to achieve with internal capsule work alone. As well as optimizing skin tailoring, external net sutures have also been used in this series to reinforce and reduce the tension on internal sutures. However, there have been occasions in which internal sutures will be used initially, and only if these have been insufficient to shape the breast, then the hemostatic net sutures can be placed secondarily—often with a sizing implant in situ.

One further advantage with external sutures is that they also support the internal reconstruction of the pocket and reduce the risk of internal sutures rupturing in the first few days postoperatively; this is particularly important when larger or submuscular implants are used. After capsule work is completed, we have found that application of the hemostatic net before any internal suturing is undertaken is beneficial to provide a stable external framework which outlines and stabilizes the patient’s optimal breast footprint.

The suture and needle size used when transfixing the net were modified by each author depending on personal preference and surgical site. This is reflective of the learning curve that has been experienced during this process. For example, 1 author predominantly uses 3/0 Ethilon sutures to form the hemostatic net, whereas 2/0 or 4/0 Monocryl sutures and 4/0 Monocryl or 3/0 Prolene or 3/0 Ethilon sutures are preferred by the other 2 surgeons, respectively.

We have found that the size of the needle appears to be more important than the size of the suture to enable adequate bites to be achieved through the skin and then into the underlying deeper tissue, such as the deep fascia. A suggested suture is a 45-cm 3/0 Ethilon suture with a 26-mm reverse cutting needle. With smaller needles, we have struggled to achieve reliable bites in the deep fascia and then re-emerge through the skin.

In our series, the length of time net sutures are left in situ (between 3 and 7 days) also varied between operators and the location of the net. In the first case report, although larger 2/0 Monocryl sutures were used to allow the net to adequately catch the pectoralis fascia over the sternal area, the risk of problematic scarring was reduced by removing the net after only 3 days. This is of course a subjective judgment and a balance between wanting the hemostatic net to serve its function as best as possible while aiming not to cause long-term scars or evidence of suture placement.

The only other documented use of the hemostatic net in breast surgery that we are aware of describes leaving the net in situ for 24 hours to reduce the risk of net suture scars in gynecomastia cases.19 Only 3 out of 24 patients included in this report experienced suture marks, and only 1 patient exhibited mild hypopigmentation at 1-year follow-up. However, the difference in ethos of application of the hemostatic net in this report is that in the gynecomastia series the sole purpose of the net was to reduce dead space and hematoma risk, whereas conversely, in our series, the net was being used as a functional reshaping tool that therefore required a longer presence to achieve its purpose.

We speculate that the hypopigmented marks might have been related to the length of time the net was left in situ, hence suggesting that in might be better to remove the net within 72 hours, rather than leaving it for a week. In the face, the net is usually left for 48 hours due to observation of a similar phenomenon. We also hypothesize that the knots of single interrupted stitches may increase the pressure subjected to the skin and consequently increase the likelihood of hyper- or hypopigmented suture marks. Therefore, we use a continuous running suture.

We acknowledge the speculative decision-making regarding the length of time the net is left in situ, and on the basis of our initial series, we are reluctant to stipulate a fixed length of time. Rather, the individual surgeon must weigh up a number of factors including the function of the net, the degree of tissue tension it is required to support, the quality of the patient’s skin, and the pigmentation/ethnicity of the patient.

We postulate that increasing the number of passages and bites of the continuous net suture might spread the tension held over the skin, and as a result, may positively impact on the quality of the main surgical scar. Overall, the authors believe that the risk of permanent hypo- or hyperpigmentation resulting from the net is low and that with fully informed consent any marks that do result are well tolerated by patients.

Interestingly, we have all had similar experiences and a similar learning curve—something we established during our collaboration on this manuscript. We have also learnt tips from each other, such as consideration of placement of the hemostatic net prior to internal sutures, which has been helpful in certain cases.

We acknowledge that the small sample size, retrospective analysis and limited follow-up in some cases are all limitations of this preliminary report. Furthermore, without having the contralateral breast as a control, it is impossible to predict outcomes if the net were not used. However, although the hemostatic net does not eliminate the need for mastopexy, the use of the net when shaping the inferior and lateral poles has been invaluable in difficult secondary cases, with only 1 case of the net failing to control excess lax skin. This observation prompted us to share with the wider plastic surgery community our positive experience with the hemostatic net in secondary breast surgery.

CONCLUSIONS

We present our initial experience with the hemostatic net in aesthetic breast surgery. The use of the net has now been extended to primary cases where implant malposition or skin tailoring issues are anticipated, thus securing its place as a part of the surgical armamentarium. We feel that our experience with the use of this technique in secondary breast implant cases is important to share with the plastic surgery community at large and believe further experience will support its useful application in challenging secondary breast surgery.

Disclosures

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Dr Goddard is a Foundation Year 1 doctor, St Helier Hospital, London, UK.

Mr Pacifico is a plastic surgeon in private practice, Tunbridge Wells, UK.

Dr Campiglio is a plastic surgeon in private practice in Milan, Italy.

Mr Waterhouse is a plastic surgeon in private practice, London, UK