-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Elbert E Vaca, Megan M Perez, Jonathan B Lamano, Sergey Y Turin, Simon Moradian, Steven Fagien, Clark Schierle, Photographic Misrepresentation on Instagram After Facial Cosmetic Surgery: Is Increased Photography Bias Associated With Greater User Engagement?, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 41, Issue 11, November 2021, Pages NP1778–NP1785, https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjab203

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Before-and-after images are commonly used on Instagram (Menlo Park, CA) to advertise aesthetic surgical treatments and are a powerful means of engaging prospective patients. Consistency between before-and-after images accurately demonstrating the postoperative result on Instagram, however, has not been systematically assessed.

The aim of this study was to systematically assess facial cosmetic surgery before-and-after photography bias on Instagram.

The authors queried 19 Instagram facial aesthetic surgery–related hashtags on 3 dates in May 2020. The “top” 9 posts associated with each hashtag (291 posts) were analyzed by 3 plastic surgeons by means of a 5-item rubric quantifying photographic discrepancies between preoperative and postoperative images. Duplicate posts and those that did not include before-and-after images of facial aesthetic surgery procedures were excluded.

A total of 3,477,178 posts were queried. Photography conditions were observed to favor visual enhancement of the postoperative result in 282/291 analyzed top posts, with an average bias score of 1.71 [1.01] out of 5. Plastic surgeons accounted for only 27.5% of top posts. Physicians practicing outside their scope of practice accounted for 2.8% of top posts. Accounts with a greater number of followers (P = 0.017) and posts originating from Asia (P = 0.013) were significantly associated with a higher postoperative photography bias score.

Photographic misrepresentation, with photography conditions biased towards enhancing the appearance of the postoperative result, is pervasive on Instagram. This pattern was observed across all physician specialties and raises significant concerns. Accounts with a greater number of followers demonstrated significantly greater postoperative photography bias, suggesting photographic misrepresentation is rewarded by greater user engagement.

“The assumption that seeing is believing makes us susceptible to visual deception.”

Kathleen Hall Jamieson1

For better or worse, social media has become ubiquitous in aesthetic surgery and is a powerful marketing and engagement tool for prospective patients seeking aesthetic treatments.2-7 These trends have accelerated at rapid pace, perhaps most notably on image-based social medial platforms such as Instagram (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA). Founded in 2010, Instagram now has over 1.1 billion monthly active users as of October 2020 and is the most commonly used platform for 18- to 35-year-olds, who on average spend >40 minutes on the platform daily.8-10

In a 2016 survey of 100 consecutive plastic surgery patients assessing social media preferences, before-and-after photographs were rated as the single most important type of content sought by prospective patients.11 However, it is well known that the fidelity of accurately representing postoperative results is reliant on rigorous standardization of clinical photography.12-20 Several factors can significantly impact the perception of aesthetic clinical photographs, including (but not limited to): lighting, camera lens selection and focal distance, backdrop, expression, head position, makeup, hairstyle, jewelry, and clothing.12-21 Attempting to control for all of these variables is challenging; however, given our high professional standards, the attempt must nonetheless be made. Standardized photography not only permits surgeons to critique their own results but is also critical for accurate demonstration of postoperative results to colleagues and prospective patients.

Anecdotally, we have noticed concerning trends in photographic misrepresentation of “before-and-after” photography on Instagram, with photographic conditions being noticeably skewed to enhance the appearance of the postoperative result. Instagram was chosen because this image-focused social media platform permitted query of the top posts by means popular facial aesthetic facial surgical procedure hashtags, and therefore, these posts represent the most frequently seen images by Instagram users interested in facial aesthetic procedures. Given the number of variables affecting clinical photography, our aim was to systematically analyze discrepancies in before-and-after images of facial aesthetic surgery on Instagram by focusing on 5 variables: (1) lighting, (2) facial expression, (3) makeup, (4) head position, and (5) framing—with framing encompassing before-and-after discrepancies in hairstyle, jewelry, photography backdrop, and clothing.

METHODS

Data from Instagram (Instagram.com) were obtained on a biweekly basis on May 3, 17, and 31, 2020. Two authors (M.M.P. and J.B.L.) queried the following hashtags for popular facial cosmetic surgery procedures:22 #blepharoplasty, #browlift, #chinaugmentation, #chinimplant, #eyelidlift, #eyelidsurgery, #facelift, #faceliftsurgery, #facialfatgrafting, #fatgrafting, #genioplasty, #liplift, #necklift, #nosejob, #nosesurgery, #rhinoplasty, #rhytidectomy, #undereyebags, #undereyecircles.

The total numbers of posts utilizing each hashtag were recorded. The top 9 posts utilizing each hashtag were further analyzed, after excluding duplicates and posts that did not show before-and-after images of facial cosmetic surgical procedures that required an incision. Demographic data were then extracted from the poster’s user profile and associated practice website including the poster’s number of Instagram followers, number of likes per post, country of origin, medical specialty (if any), and certifying medical board (American Board of Plastic Surgery [ABPS], American Board of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery [ABO-HNS], American Board of Ophthalmology [ABO], American Board of Dermatology [ABD], American Board of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery [ABOMS], or other). Poster’s country of origin was further organized into geographic regions: (1) United States/Canada, (2) Europe, (3) Asia, (4) Middle East,23 (5) Latin America/Caribbean, and (6) Australia. We further tracked if the source of the post was a patient. If the source of the Instagram post did not fall into any of these categories (ie, fan page, consultant, etc), then the poster was categorized as “other.”

Posts were also categorized if they fell within or outside of the practitioner’s scope of practice. Scope of practice was determined as offering procedures outlined by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education24 for a respective residency or additional fellowship training in a specific area. Offering procedures outside of these areas was defined as out of scope. For example, dermatologists were considered to be practicing outside their scope of practice if they offered aesthetic surgical procedures outside of injectables, lasers, chemical peels, or minimally invasive procedures. Practitioners who performed aesthetic surgical procedures and advertising themselves as certified by the American Board of Cosmetic Surgery (ABCS) were considered to be practicing outside their scope of practice because the ABCS is not recognized by the American Board of Medical Specialties.

Before-and-after screenshots of the analyzed top posts were rated by 3 plastic surgeons (E.E.V., S.Y.T., C.S.) utilizing a photography bias score developed by this study’s 2 principal authors (E.E.V and C.S.), after blinding for the poster’s username and country of origin. The clinical photography bias score (CPBS) is composed of 5 components: (1) lighting; (2) facial expression; (3) makeup; (4) head position; and (5) framing. Framing was defined to include hairstyle, jewelry, photography, and/or clothing “before-and-after” discrepancies that appeared to influence the aesthetic perception of a clinical photograph. The raters could select a score of –1, 0, or +1 for each of the 5 components, with +1 indicating that the photographic parameter was perceived to enhance the postoperative appearance, –1 indicating that the photographic parameter was perceived to enhance the preoperative appearance, and 0 signifying a neutral or absence of difference between the pre- and postoperative image (Table 1). The total CPBS ranged from –5 to +5, with a higher positive score indicating a greater bias favoring the appearance of the postoperative image. The raters were provided with all available views, if available (eg, frontal, oblique, lateral) and were instructed to record their bias score if they observed clear discrepancies between before-and-after images on any of the provided views (eg, facelift patient—neck extended in postoperative lateral view compared to preoperative view = +1 for “head position”). Prior to rating, raters were provided with a sample of 20 before-and-after images with a spectrum of CPBS scores agreed upon by E.E.V. and C.S.

| Bias score . | Lighting . | Facial expression . | Makeup . | Head position . | Framing . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +1 (favors postoperative image) | Lighting discrepancy resulting in increased shadowing effect on pre- vs postoperative image Lighting discrepancy resulting in washout effect that blunts shadows on post- vs preoperative image | Perception of any increased degree of sad or melancholy expression on pre- vs postoperative image Perception of any degree of smile or eye squinting on post- vs preoperative image | Perception of discrepancy where more favorable makeup is worn on the post- vs preoperative image | Perception of more flattering head position on post- vs preoperative image, for example: Neck extension: favors facelift, genioplasty, rhinoplasty, lower blepharoplasty, lip lift Neck flexion: favors upper blepharoplasty, browlift | Perception of more favorable photography condition on post- vs preoperative image including: —Hairstyle —Jewelry —Clothing —Image background Example: Better hairstyle or if hair/jewelry/clothing obscure surgical incisions in postoperative image |

| 0 (neutral) | No perceived difference in pre- vs postoperative image | No perceived difference in pre- vs postoperative image | No perceived difference in pre- vs postoperative image | No perceived difference in pre- vs postoperative image | No perceived difference in pre- vs postoperative image |

| –1 (favors preoperative image) | Lighting condition enhances or favors the preoperative image | Facial expression enhances or favors the preoperative image | Makeup enhances or favors the preoperative image | Head position enhances or favors the preoperative image | Framing enhances or favors the preoperative image |

| Total score (–5 to +5): | _________ |

| Bias score . | Lighting . | Facial expression . | Makeup . | Head position . | Framing . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +1 (favors postoperative image) | Lighting discrepancy resulting in increased shadowing effect on pre- vs postoperative image Lighting discrepancy resulting in washout effect that blunts shadows on post- vs preoperative image | Perception of any increased degree of sad or melancholy expression on pre- vs postoperative image Perception of any degree of smile or eye squinting on post- vs preoperative image | Perception of discrepancy where more favorable makeup is worn on the post- vs preoperative image | Perception of more flattering head position on post- vs preoperative image, for example: Neck extension: favors facelift, genioplasty, rhinoplasty, lower blepharoplasty, lip lift Neck flexion: favors upper blepharoplasty, browlift | Perception of more favorable photography condition on post- vs preoperative image including: —Hairstyle —Jewelry —Clothing —Image background Example: Better hairstyle or if hair/jewelry/clothing obscure surgical incisions in postoperative image |

| 0 (neutral) | No perceived difference in pre- vs postoperative image | No perceived difference in pre- vs postoperative image | No perceived difference in pre- vs postoperative image | No perceived difference in pre- vs postoperative image | No perceived difference in pre- vs postoperative image |

| –1 (favors preoperative image) | Lighting condition enhances or favors the preoperative image | Facial expression enhances or favors the preoperative image | Makeup enhances or favors the preoperative image | Head position enhances or favors the preoperative image | Framing enhances or favors the preoperative image |

| Total score (–5 to +5): | _________ |

| Bias score . | Lighting . | Facial expression . | Makeup . | Head position . | Framing . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +1 (favors postoperative image) | Lighting discrepancy resulting in increased shadowing effect on pre- vs postoperative image Lighting discrepancy resulting in washout effect that blunts shadows on post- vs preoperative image | Perception of any increased degree of sad or melancholy expression on pre- vs postoperative image Perception of any degree of smile or eye squinting on post- vs preoperative image | Perception of discrepancy where more favorable makeup is worn on the post- vs preoperative image | Perception of more flattering head position on post- vs preoperative image, for example: Neck extension: favors facelift, genioplasty, rhinoplasty, lower blepharoplasty, lip lift Neck flexion: favors upper blepharoplasty, browlift | Perception of more favorable photography condition on post- vs preoperative image including: —Hairstyle —Jewelry —Clothing —Image background Example: Better hairstyle or if hair/jewelry/clothing obscure surgical incisions in postoperative image |

| 0 (neutral) | No perceived difference in pre- vs postoperative image | No perceived difference in pre- vs postoperative image | No perceived difference in pre- vs postoperative image | No perceived difference in pre- vs postoperative image | No perceived difference in pre- vs postoperative image |

| –1 (favors preoperative image) | Lighting condition enhances or favors the preoperative image | Facial expression enhances or favors the preoperative image | Makeup enhances or favors the preoperative image | Head position enhances or favors the preoperative image | Framing enhances or favors the preoperative image |

| Total score (–5 to +5): | _________ |

| Bias score . | Lighting . | Facial expression . | Makeup . | Head position . | Framing . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +1 (favors postoperative image) | Lighting discrepancy resulting in increased shadowing effect on pre- vs postoperative image Lighting discrepancy resulting in washout effect that blunts shadows on post- vs preoperative image | Perception of any increased degree of sad or melancholy expression on pre- vs postoperative image Perception of any degree of smile or eye squinting on post- vs preoperative image | Perception of discrepancy where more favorable makeup is worn on the post- vs preoperative image | Perception of more flattering head position on post- vs preoperative image, for example: Neck extension: favors facelift, genioplasty, rhinoplasty, lower blepharoplasty, lip lift Neck flexion: favors upper blepharoplasty, browlift | Perception of more favorable photography condition on post- vs preoperative image including: —Hairstyle —Jewelry —Clothing —Image background Example: Better hairstyle or if hair/jewelry/clothing obscure surgical incisions in postoperative image |

| 0 (neutral) | No perceived difference in pre- vs postoperative image | No perceived difference in pre- vs postoperative image | No perceived difference in pre- vs postoperative image | No perceived difference in pre- vs postoperative image | No perceived difference in pre- vs postoperative image |

| –1 (favors preoperative image) | Lighting condition enhances or favors the preoperative image | Facial expression enhances or favors the preoperative image | Makeup enhances or favors the preoperative image | Head position enhances or favors the preoperative image | Framing enhances or favors the preoperative image |

| Total score (–5 to +5): | _________ |

Statistical analysis was performed with SSPS. Mean [standard deviation] photography bias scores for the 3 raters (E.E.V., S.Y.T., C.S.) were reported and compared across provider specialty type, board certification, procedure type, and geographic region with one-way analysis of variance. Significance was set at P < 0.05. Number of likes and follower counts were correlated with photography bias scores by both Pearson and Spearman coefficients. Planned independent-sample t tests were conducted between individual groups as a post-hoc analysis. Groups were then divided into high photography bias (bias score ≥1.71) and low photography bias (bias score <1.71) because the average photography bias score was 1.71. Chi-squared tests were performed comparing location, provider, board certification, and procedure across the 2 patient groups. Independent-sample t tests compared the number of followers and likes between high and low photography bias score groups.

RESULTS

A total of 3,477,178 posts were queried (Table 2) that utilized the selected hashtags evaluated in this study and 291 unique posts were analyzed for photography bias. Of the 291 unique posts analyzed, only 80 accounts (27.5%) were operated by plastic surgeons (Table 3). Other physicians represented included otolaryngology/facial plastic surgeons (135 accounts), ophthalmology (37 accounts), oral and maxillofacial surgery (17 accounts), dermatology (1 account), general surgery (2 accounts), pediatric surgery (2 accounts), and dentists (3 accounts). One-hundred and seventy posts were by US/Canada accounts and 121 by international accounts (Table 4). In regards specifically to rhinoplasty posts, 56.9% were from Middle Eastern–based accounts. Number of likes per post ranged from 9 to 26,166, with an average of 1804 likes. Number of followers per account ranged from 476 to 2,900,000, with an average of 38,974 followers.

| Procedure hashtag . | N . |

|---|---|

| #blepharoplasty | 178,263 |

| #browlift | 301,652 |

| #liplift | 45,931 |

| #chinaugmentation | 55,534 |

| #chinimplant | 18,165 |

| #eyelidlift | 24,782 |

| #eyelidsurgery | 81,436 |

| #facelift | 1,081,679 |

| #faceliftsurgery | 6287 |

| #facialfatgrafting | 1435 |

| #fatgrafting | 1435 |

| #genioplasty | 11,862 |

| #necklift | 93,875 |

| #nosejob | 644,406 |

| #nosesurgery | 148,173 |

| #rhinoplasty | 960,646 |

| #rhytidectomy | 3499 |

| #undereyebags | 51,677 |

| Total | 3,778,337 |

| Procedure hashtag . | N . |

|---|---|

| #blepharoplasty | 178,263 |

| #browlift | 301,652 |

| #liplift | 45,931 |

| #chinaugmentation | 55,534 |

| #chinimplant | 18,165 |

| #eyelidlift | 24,782 |

| #eyelidsurgery | 81,436 |

| #facelift | 1,081,679 |

| #faceliftsurgery | 6287 |

| #facialfatgrafting | 1435 |

| #fatgrafting | 1435 |

| #genioplasty | 11,862 |

| #necklift | 93,875 |

| #nosejob | 644,406 |

| #nosesurgery | 148,173 |

| #rhinoplasty | 960,646 |

| #rhytidectomy | 3499 |

| #undereyebags | 51,677 |

| Total | 3,778,337 |

| Procedure hashtag . | N . |

|---|---|

| #blepharoplasty | 178,263 |

| #browlift | 301,652 |

| #liplift | 45,931 |

| #chinaugmentation | 55,534 |

| #chinimplant | 18,165 |

| #eyelidlift | 24,782 |

| #eyelidsurgery | 81,436 |

| #facelift | 1,081,679 |

| #faceliftsurgery | 6287 |

| #facialfatgrafting | 1435 |

| #fatgrafting | 1435 |

| #genioplasty | 11,862 |

| #necklift | 93,875 |

| #nosejob | 644,406 |

| #nosesurgery | 148,173 |

| #rhinoplasty | 960,646 |

| #rhytidectomy | 3499 |

| #undereyebags | 51,677 |

| Total | 3,778,337 |

| Procedure hashtag . | N . |

|---|---|

| #blepharoplasty | 178,263 |

| #browlift | 301,652 |

| #liplift | 45,931 |

| #chinaugmentation | 55,534 |

| #chinimplant | 18,165 |

| #eyelidlift | 24,782 |

| #eyelidsurgery | 81,436 |

| #facelift | 1,081,679 |

| #faceliftsurgery | 6287 |

| #facialfatgrafting | 1435 |

| #fatgrafting | 1435 |

| #genioplasty | 11,862 |

| #necklift | 93,875 |

| #nosejob | 644,406 |

| #nosesurgery | 148,173 |

| #rhinoplasty | 960,646 |

| #rhytidectomy | 3499 |

| #undereyebags | 51,677 |

| Total | 3,778,337 |

| Provider specialty . | N (%) . |

|---|---|

| Plastic surgery | 80 (27.6) |

| ENT/facial plastic surgery | 135 (46.4) |

| Ophthalmology | 37 (12.7) |

| Dermatology | 1 (0.003) |

| Oral/maxillofacial surgery | 17 (0.06) |

| General surgery | 2 (0.007) |

| Pediatric surgery | 2 (0.007) |

| Dentistry | 3 (0.033) |

| Othera | 8 (0.027) |

| Unidentified | 6 (0.021) |

| Total | 291 (100) |

| Provider specialty . | N (%) . |

|---|---|

| Plastic surgery | 80 (27.6) |

| ENT/facial plastic surgery | 135 (46.4) |

| Ophthalmology | 37 (12.7) |

| Dermatology | 1 (0.003) |

| Oral/maxillofacial surgery | 17 (0.06) |

| General surgery | 2 (0.007) |

| Pediatric surgery | 2 (0.007) |

| Dentistry | 3 (0.033) |

| Othera | 8 (0.027) |

| Unidentified | 6 (0.021) |

| Total | 291 (100) |

ENT, ear, nose, and throat.

aOther includes 4 patients, 2 global aesthetic consultants, 1 beauty supply company, and 1 cosmetic tourism agency

| Provider specialty . | N (%) . |

|---|---|

| Plastic surgery | 80 (27.6) |

| ENT/facial plastic surgery | 135 (46.4) |

| Ophthalmology | 37 (12.7) |

| Dermatology | 1 (0.003) |

| Oral/maxillofacial surgery | 17 (0.06) |

| General surgery | 2 (0.007) |

| Pediatric surgery | 2 (0.007) |

| Dentistry | 3 (0.033) |

| Othera | 8 (0.027) |

| Unidentified | 6 (0.021) |

| Total | 291 (100) |

| Provider specialty . | N (%) . |

|---|---|

| Plastic surgery | 80 (27.6) |

| ENT/facial plastic surgery | 135 (46.4) |

| Ophthalmology | 37 (12.7) |

| Dermatology | 1 (0.003) |

| Oral/maxillofacial surgery | 17 (0.06) |

| General surgery | 2 (0.007) |

| Pediatric surgery | 2 (0.007) |

| Dentistry | 3 (0.033) |

| Othera | 8 (0.027) |

| Unidentified | 6 (0.021) |

| Total | 291 (100) |

ENT, ear, nose, and throat.

aOther includes 4 patients, 2 global aesthetic consultants, 1 beauty supply company, and 1 cosmetic tourism agency

| Location . | N (%) . |

|---|---|

| United States/Canada | 170 (58.4) |

| Middle East | 63 (21.6) |

| Europe | 24 (8.2) |

| Latin America/Caribbean | 16 (5.5) |

| Australia | 10 (3.4) |

| Asia | 8 (2.7) |

| Total | 291 (100) |

| Location . | N (%) . |

|---|---|

| United States/Canada | 170 (58.4) |

| Middle East | 63 (21.6) |

| Europe | 24 (8.2) |

| Latin America/Caribbean | 16 (5.5) |

| Australia | 10 (3.4) |

| Asia | 8 (2.7) |

| Total | 291 (100) |

| Location . | N (%) . |

|---|---|

| United States/Canada | 170 (58.4) |

| Middle East | 63 (21.6) |

| Europe | 24 (8.2) |

| Latin America/Caribbean | 16 (5.5) |

| Australia | 10 (3.4) |

| Asia | 8 (2.7) |

| Total | 291 (100) |

| Location . | N (%) . |

|---|---|

| United States/Canada | 170 (58.4) |

| Middle East | 63 (21.6) |

| Europe | 24 (8.2) |

| Latin America/Caribbean | 16 (5.5) |

| Australia | 10 (3.4) |

| Asia | 8 (2.7) |

| Total | 291 (100) |

American board certification was also evaluated among US physicians and it was found that the majority were certified by the ABO-HNS (48.6%; 72/148), the ABPS (29.7%; 44/148), and the ABO (13.5%; 20/148) (Table 5). Six accounts (8/291 posts; 2.7%) were found to be marketing outside the scope of their practice and included the following provider types: 1 general surgeon, 2 dentists, 1 ophthalmologist, 1 oral/maxillofacial surgeons, and 1 dermatologist (Table 6).

| Board certification . | N (%) . |

|---|---|

| ABPS | 40 (27.0) |

| ABO-HNS | 72 (48.6) |

| ABO | 20 (13.5) |

| ABD | 1 (0.67) |

| ABOMSa | 11 (7.4) |

| Totalb | 148 (100) |

| Board certification . | N (%) . |

|---|---|

| ABPS | 40 (27.0) |

| ABO-HNS | 72 (48.6) |

| ABO | 20 (13.5) |

| ABD | 1 (0.67) |

| ABOMSa | 11 (7.4) |

| Totalb | 148 (100) |

ABD, American Board of Dermatology; ABO, American Board of Ophthalmology; ABO-HNS, American Board of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery; ABOMS, American Board of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery; ABPS, American Board of Plastic Surgery.

aOne provider was double boarded in both otolaryngology and oral/maxillofacial surgery and counted twice, once in each category.

bTotal N = 148 providers after exclusion of: 121 foreign accounts, 8 nonphysician accounts (dentist, patients, consultants), and 15 unidentified society membership accounts.

| Board certification . | N (%) . |

|---|---|

| ABPS | 40 (27.0) |

| ABO-HNS | 72 (48.6) |

| ABO | 20 (13.5) |

| ABD | 1 (0.67) |

| ABOMSa | 11 (7.4) |

| Totalb | 148 (100) |

| Board certification . | N (%) . |

|---|---|

| ABPS | 40 (27.0) |

| ABO-HNS | 72 (48.6) |

| ABO | 20 (13.5) |

| ABD | 1 (0.67) |

| ABOMSa | 11 (7.4) |

| Totalb | 148 (100) |

ABD, American Board of Dermatology; ABO, American Board of Ophthalmology; ABO-HNS, American Board of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery; ABOMS, American Board of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery; ABPS, American Board of Plastic Surgery.

aOne provider was double boarded in both otolaryngology and oral/maxillofacial surgery and counted twice, once in each category.

bTotal N = 148 providers after exclusion of: 121 foreign accounts, 8 nonphysician accounts (dentist, patients, consultants), and 15 unidentified society membership accounts.

| Provider type . | Location . | Society membershipb . | Procedure . |

|---|---|---|---|

| General surgeon | Australia | Facelift and neck liposuction | |

| Dentista | Brazil | Lip lift × 2 | |

| Ophthalmologist | United States | ABO | Facelift |

| Dentist | Portugal | Rhinoplasty | |

| Oral/maxillofacial surgeona | Russia | Rhinoplasty × 2 | |

| Dermatologist | United States | ABD | Upper and lower blepharoplasty |

| Provider type . | Location . | Society membershipb . | Procedure . |

|---|---|---|---|

| General surgeon | Australia | Facelift and neck liposuction | |

| Dentista | Brazil | Lip lift × 2 | |

| Ophthalmologist | United States | ABO | Facelift |

| Dentist | Portugal | Rhinoplasty | |

| Oral/maxillofacial surgeona | Russia | Rhinoplasty × 2 | |

| Dermatologist | United States | ABD | Upper and lower blepharoplasty |

ABD, American Board of Dermatology; ABO, American Board of Ophthalmology.

aAccount had 2 independent posts considered outside of scope.

bSociety membership was only recorded for US physicians.

| Provider type . | Location . | Society membershipb . | Procedure . |

|---|---|---|---|

| General surgeon | Australia | Facelift and neck liposuction | |

| Dentista | Brazil | Lip lift × 2 | |

| Ophthalmologist | United States | ABO | Facelift |

| Dentist | Portugal | Rhinoplasty | |

| Oral/maxillofacial surgeona | Russia | Rhinoplasty × 2 | |

| Dermatologist | United States | ABD | Upper and lower blepharoplasty |

| Provider type . | Location . | Society membershipb . | Procedure . |

|---|---|---|---|

| General surgeon | Australia | Facelift and neck liposuction | |

| Dentista | Brazil | Lip lift × 2 | |

| Ophthalmologist | United States | ABO | Facelift |

| Dentist | Portugal | Rhinoplasty | |

| Oral/maxillofacial surgeona | Russia | Rhinoplasty × 2 | |

| Dermatologist | United States | ABD | Upper and lower blepharoplasty |

ABD, American Board of Dermatology; ABO, American Board of Ophthalmology.

aAccount had 2 independent posts considered outside of scope.

bSociety membership was only recorded for US physicians.

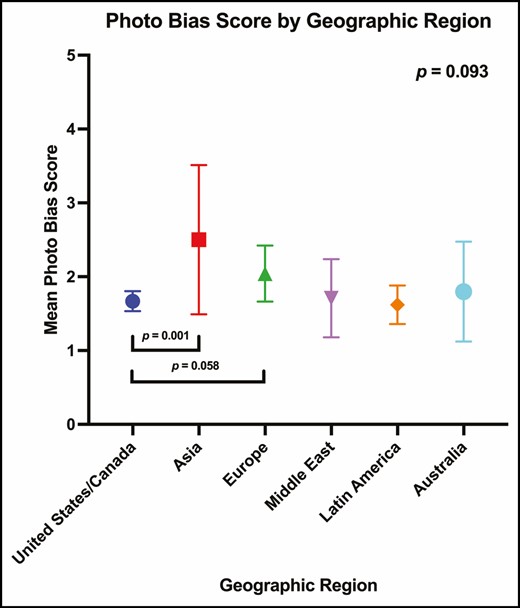

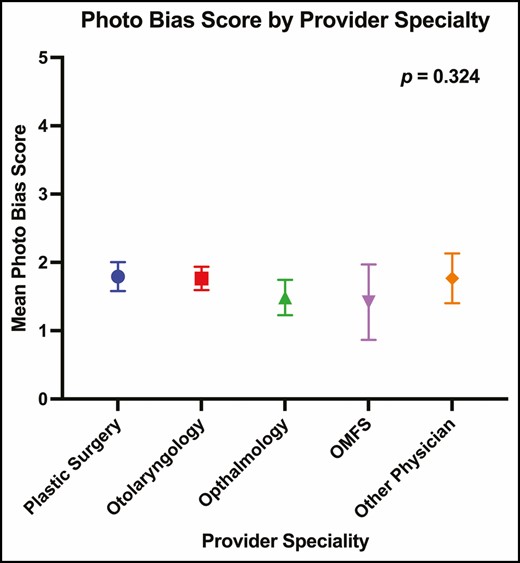

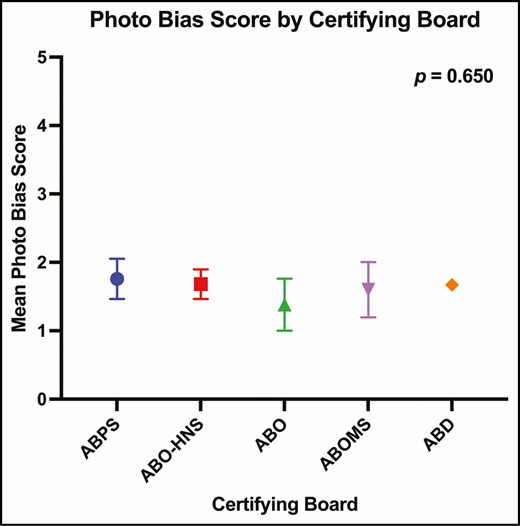

Overall, the average photography bias score was 1.71 [1.01] out of 5. Notably, there were no posts with a negative average photogaphy bias score and only 9 posts with a neutral score, indicating that photography conditions favored visual enhancement of the postoperative result in nearly all analyzed posts. Of the 9 posts with a photography bias score of 0, 5 were from plastic surgeons and 4 from otolaryngologists. When photography bias scores were compared across categories via 1-way analysis of variance, there was no significant difference in photography bias scores among geographic region (F = 1.909, P = 0.093), provider specialty (F = 1.171, P = 0.324), board certification (F = 0.619, P = 0.650), or procedure (F = 0.675, P = 0.827) (Figures 1-3). Planned t tests were notable for a significantly higher photography bias score in Asia than the United States/Canada (mean difference of 0.83, t = –2.522, P = 0.013) and a trend toward a higher photography bias score in Europe vs the United States/Canada (mean difference 0.37, t = –1.906, P = 0.058).

There was a significant positive correlation between a higher photography bias score and a greater number of Instagram account followers (Pearson, r = 0.140, P = 0.017). The remaining correlations were not significant (Spearman, followers vs photography bias, r = 0.104, P = 0.076; Pearson, likes vs photography bias, r = 0.079, P = 0.201; Spearman, likes vs photography bias, r = 0.118, P = 0.056). Chi-squared tests comparing the number of posts with high bias (≥1.71) and low bias (<1.71) found no difference across location, provider, board certification, or procedure (data not shown). However, posts with high photography bias had significantly more followers (t = –2.213, P = 0.035) with an average of 12,831 more followers in the high-bias group and a trending difference in the number of likes (t = –1.680, P = 0.095) with an average of 835 more likes in the high-bias group.

Discussion

Seeing the postoperative result should be the truest measure, at least in theory, of the surgeon’s skill and aesthetic judgment. Indeed, before-and-after photographs have been valued as the single most important type of content sought out by prospective plastic surgery patients.11 In a 2018 crowdsource survey, respondents reported that social media platforms were the single most influential online source they would use to select an aesthetic surgeon.6 Given that the 21st-century patient is regarded as a healthcare “consumer,” 7 before-and-after images on social media platforms are critical in the decision-making process of patients when they “shop” for a plastic surgeon. Unfortunately, images may tell only a curated version of the postoperative result.

Discrepancies in lighting, expression, head position, makeup, and hairstyle significantly influence facial appearance.12-21,25 Lambros, in a thought-provoking presentation, demonstrated impressive postoperative results after facial cosmetic procedures, only later revealing that the subjects had not undergone any intervention, with the apparent improvements being solely due to lighting modifications.13 To that end, our aim was to investigate the prevalence of before-and-after photographic discrepancies on Instagram because this social medial platform is commonly used by prospective aesthetic surgery patients.

The average photography bias score in this study was 1.71/5, with none of the top posts having a negative bias score, strongly indicating there is systemic bias towards enhancing the appearance of the postoperative result by manipulating before-and-after photography conditions. Furthermore, we demonstrated a significantly higher photography bias score in posts originating from Asia than in posts originating from the United States/Canada (mean difference, 0.83; P = 0.01). We hypothesize that greater facial cosmetic postoperative photography misrepresentation in Asia may be another permutation of a known trend in Asia, particularly in China, where academic misconduct, including plagiarism, data fabrication, and intellectual property theft, have garnered attention from both international governments and major scientific journals, including Nature.26 Another possibility is that this is due to type 1 error caused by the small number of top posts from Asia. Interestingly, we did observe a significant positive correlation between photography bias score and number of account followers (P = 0.017). Concerningly, this suggests that a greater number of Instagram users are drawn to Instagram accounts that practice a greater degree of postoperative photographic misrepresentation. There was a trend between number of likes per post and a higher photography bias score, although this was not significant (P = 0.076). This may suggest that number of followers is only partially correlated with number of likes—nonetheless, accounts with greater postoperative photography bias seem to garner more social media traffic.

Only 28% of top Instagram facial aesthetic surgery posts were from plastic surgeons, with 46% and 13% of posts from ear, nose, and throat/facial plastic surgeons and ophthalmologists, respectively. Alarmingly, the power of Instagram for patient engagement has not gone unnoticed by practitioners who advertise invasive procedures outside their scope of practice. Eight top posts (2.7%) were by practitioners who advertised procedures outside their scope of practice, including a general surgeon (facelift), an oral and maxillofacial surgeon (rhinoplasty × 2), a dentist (lip lift and rhinoplasty), an ophthalmologist (facelift), and a dermatologist (blepharoplasty) (Table 6). In a prior study by our group conducted in 2017 where top Instagram posts were queried with face, breast, and body aesthetic surgery hashtags, 11.6% of top posts were from physicians practicing outside their scope of practice,4 raising significant patient safety concerns. In this present study, as compared to our prior 2017 study,4 the lower proportion of posts from plastic surgeons is likely due to our focus on facial cosmetic procedures, thus there was a higher proportion of ear, nose, and throat/facial plastic surgeons and ophthalmologists. In addition, there was a lower proportion of physicians advertising procedures outside their scope of practice (2.7% vs 11.6%), which we believe is due to a lower number of general surgeons and gynecologists because they are less likely to advertise facial cosmetic surgery than breast and body procedures.27

In a 2010 study examining the training background of providers offering liposuction in Southern California, only 62% were board-certified plastic surgeons, with dermatologists and physicians with no formal surgical training compromising a significant proportion of practitioners.28 In a 2013 Google search of 7500 websites of clinicians advertising themselves as plastic surgeons, 22% were not board certified by the ABPS.29 Furthermore, a 2018 American crowdsource survey showed that 96% of general public respondents did not know what type of board certification a plastic surgeon should hold—specifically, 42% of respondents believed a surgeon certified by the ABCS is a plastic surgeon.6 Unfortunately, the lack of education of the general public, exacerbated by the relative absence of scope of practice regulation, has in part permitted inadequately trained practitioners to gain traction in social media platforms to advertise plastic surgery procedures. This poses not only a risk to our specialty, but also to patient safety30 because patients make important decisions on which practitioner they will trust to perform their aesthetic surgery by referencing before-and-after photography on social media.6,11

In addition to poor education of the lay public,4-6,27-29 other factors have contributed to the infiltration of nonqualified practitioners into the aesthetic surgery market. Fierce competition has been amplified by social media,5,31,32 which along with trivialization of aesthetic surgery, has created an appetite for extreme, attention-grabbing “results” while minimizing the risks of potential complications. In addition, there are greater market forces at play, including lower physician insurance reimbursements,33 that have increased the economic pressure on healthcare providers with no formal aesthetic training to seek other revenue streams. This is a slippery slope: once a patient receives less-invasive cosmetic treatments, these patients may be more likely to undergo invasive surgical procedures once they establish rapport with the practitioner.34,35 The ability for unqualified practitioners to perform procedures outside their scope of practice, exacerbated by an uneducated public and fierce competition in our present digital age, has likely further contributed to the “keeping up with the Jones’s” phenomenon6,32 to demonstrate impressive results.

The question, however, remains: how does one attempt to curtail photographic misrepresentation of before-and-after results? This is a difficult and multifaceted problem—by no means do we claim to know the answer. The pressure to distinguish oneself as a surgeon to aesthetic healthcare consumers has created the ideal culture medium for a before-and-after photography “arms race” to thrive, and is further reinforced by Instagram’s algorithm/business model which is designed to maximize the amount of time users spend on the platform.36 Enforcement of more rigorous photography advertising standards by the ABPS on its members would be a naive and ineffective measure at best, especially in the absence of other frontrunning measures. Photography standards would be difficult to enforce and define, would add further regulatory burdens on our members, and would put our members in a quandary as other non-ABPS members will continue their current advertising practices. An attempt must be made to level the playing field by further increasing the barrier of entry for unqualified practitioners. The first step lies with public education. The American Society of Plastic Surgeons has continued to work on promoting awareness of ABPS board certification and our rigorous training and safety standards to distinguish ourselves from other specialties.37 The next step lies with legislation at the state and national level. In a landmark 2018 decision by the Medical Board of California, ABCS members are no longer permitted to advertise themselves as board certified in the state of California.38 If other states follow suit, this will surely be welcome news to properly trained surgeons.

This study is not without its limitations. First, we queried only the top posts for a limited number of facial cosmetic surgery hashtags—we suspect there may be a higher prevalence of physicians who advertise facial cosmetic procedures on Instagram outside their scope of practice. Second, we only queried Instagram images on 3 dates (2 weeks apart)—social media content continually changes and the observed trends may vary; however, this study improved upon our prior studies,4 as we previously only queried top posts on a single date. Third, there are inherent shortfalls to any proposed measurement scale. The senior authors of this study (E.E.V and C.S.) attempted to add objectivity to an otherwise subjective assessment of discrepancies in clinical photography conditions. Our 5-component photography bias scale (Table 2) was not designed to capture the severity of the indivdual components of the scale (ie, mild vs severe neck extension in a postoperative facelift photograph would both count as +1 on the scale). Furthermore, we decided to focus our scale on a few parameters, making it by no means completely comprehensive—nonetheless, this offers insight into the prevalence of photography bias. Fourth, this study may be underpowered, particularly when assessing photography bias trends in less-represented geographic areas and for physicians practicing outside their scope of practice. Nonetheless, this study is the first to attempt to systematically analyze photographic misrepresentation on a social media platform. Future studies may aim at assessing before-and-after photography bias for different types of cosmetic procedures, different digital platforms, and for a greater number of data points to elucidate other trends.

Conclusions

Consistency between before-and-after photographic conditions is essential for accurate representation of postoperative results. Unfortunately, visual enhancement of facial aesthetic surgery results via photographic misrepresentation is pervasive on Instagram, likely exacerbated by the competitive pressures of social media and the aesthetic surgery industry.

Disclosures

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.