-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Sterling E Braun, Michaela K O’Connor, Margaret M Hornick, Melissa E Cullom, James A Butterworth, Global Trends in Plastic Surgery on Social Media: Analysis of 2 Million Posts, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 41, Issue 11, November 2021, Pages 1323–1332, https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjab185

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Plastic surgeons and patients increasingly use social media. Despite evidence implicating its importance in plastic surgery, the large volume of data has made social media difficult to study.

The aim of this study was to provide a comprehensive assessment of plastic surgery social media content worldwide by utilizing techniques for analyzing large-scale data.

The hashtag “#PlasticSurgery” was used to search public Instagram posts. Metadata were collected from posts between December 2018 and August 2020. In addition to descriptive analysis, 2 instruments were created to characterize textual data: a multilingual dictionary of procedural hashtags and a rule-based text classification model to categorize the source of the post.

Plastic surgery content yielded more than 2 million posts, 369 million likes, and 6 billion views globally over the 21-month study. The United States had the most posts of 182 countries studied (26.8%, 566,206). Various other regions had substantial presence including Istanbul, Turkey, which led all cities (4.8%, 102,208). The classification model achieved high accuracy (94.9%) and strong agreement with independent raters (κ = 0.88). Providers accounted for 40% of all posts (847,356) and included the categories physician (28%), plastic surgery (9%), advanced practice practitioners and nurses (1.6%), facial plastics (1.3%), and oculoplastics (0.2%). Content between plastic surgery and non–plastic surgery groups demonstrated high textual similarity, and only 1.4% of posts had a verified source.

Plastic surgery content has immense global reach in social media. Textual similarity between groups coupled with the lack of an effective verification mechanism presents challenges in discerning the source and veracity of information.

Clinicians and trainees across a multitude of specialties are increasingly exploiting social media for professional purposes.1-9 Patients also use the platforms to chronicle experiences, seek and offer support, learn about procedures, and evaluate providers.10,11 For plastic surgeons, social media has become indispensable for patient outreach and recruitment.12-19 Of the social media platforms, Instagram (Facebook, Menlo Park, CA) has demonstrated one of the strongest impacts for plastic surgery practices.20,21 With over 1 billion active monthly users, 130 million in the United States alone, Instagram is one of the most popular social media platforms.22

Despite evidence implicating the importance of medical discourse on social media platforms, social media has been difficult to study due to the volume of content. Current literature has used a narrow scope of analysis and small sample sizes to overcome these challenges.5,23 Our goal was to provide a comprehensive assessment of plastic surgery content on Instagram on a global scale.

METHODS

We collected metadata from publicly available Instagram posts containing the hashtag “#PlasticSurgery” between December 2018 and August 2020. The search was conducted in August 2020 by the corresponding author (S.E.B.) and reviewed by 3 authors (M.K.O., M.M.H., and M.E.C.). There were no disagreements regarding the results of the search. We then created 2 instruments to characterize the textual data: a multilingual word dictionary to identify surgical procedures, and a rule-based text-classification model to characterize the source of the post. Descriptive analysis was performed to assess the nature of the content as well as its reach amongst the public. The study did not meet the criteria for human subject research provided by the University of Kansas Medical Center IRB and was exempt from review. We followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines for cross-sectional studies.24 Further description of the methods, representative figures, and code used for analysis are presented in the Appendix.

Data Processing

Data collection and analysis were performed with Node.js version 14.15.0 (OpenJS Foundation) and R software version 3.6.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).25 Data were evaluated for completeness with summary statistics and visualized in a time series plot (Appendix). Duplicates were removed from the data by retaining observations with a unique timestamp, caption text, and screen name. Data for likes and comments were present for all observations. View counts were present for video and story content. For image posts, the view counts were imputed by the k-nearest-neighbors method considering like and comment counts.26

Geographic Data

Location data were available for posts that included a publicly displayed location tag. Named locations, typically a city or neighborhood, were converted to geographic coordinates in latitude and longitude with the Google Geocoding API (Google, Mountain View, CA) (Appendix, Section 1).27 Coordinates were grouped into geographic clusters with a 20-km radius to allow for analyses of representative areas (ie, different neighborhoods or districts within a city). The most common cluster for each account was used to impute missing location data for that account.

Text Analysis

We created a multilingual procedure dictionary to analyze the post captions. The most common non–English language tags were identified and translated with the Google Cloud Translation API.28 The terms were reviewed manually and those pertinent to plastic surgery were categorized by procedure type (Appendix, Section 2). This allowed us to characterize tags from more than 30 languages (Figure 1). Sentiment analysis was performed to gauge reception in the comments. We used the Jockers Rinker lexicon and a validated lexicon for emojis.29 For this process, a numeric value is assigned to sentences based on the associated positivity or negativity considering adjacent words that negate or amplify the effect. The sum of the comment sentiments and number of positive and negative comments were tabulated.

Account Type Classification

We designed a rule-based text classification model to characterize the account as 1 of 7 types: Plastic Surgery, ENT (ear nose and throat) Facial Plastics, Oculoplastics (ophthalmology), Physician (ie, without formal plastic surgery training), APP & RN (advanced practice practitioners and registered nurses), Organization, and Other.

‘Plastic Surgery’ included those certified by the American Board of Plastic Surgery (ABPS) or verified international member surgeons of the American Society of Plastic Surgery (ASPS).30,31 ‘ENT Facial Plastics’ included members certified by the American Board of Facial Plastic Surgery (ABFPS).32 ‘Oculoplastics’ included members of the American Society of Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeons (ASOPRS).33 For the ‘Plastic Surgery’, ‘ENT Facial Plastics’, and ‘Oculoplastics’ categories, classification was determined by comparing information from respective board organizations and information with the username and screenname of the post. Geographic data were compared to exclude false positive matches to common names.

‘Physician’ included physicians who did not have ABPS, ASPS, ABFPS, or ASOPRS certification. ‘APP & RN’ included advanced practice practitioners and registered nurses serving as affiliated staff and/or providers. Classification within these categories was determined by presence of a professional title or academic degree identified through matching of a regular expression. ‘Organization’ represented organizational accounts of a practice (ie, clinic, medical spa, ambulatory surgical center, etc). ‘Other’ represented accounts that remained uncategorized.

Validation and Predictive Accuracy

Validation was performed on a random, representative sample of 2500 unique accounts. The sample was independently evaluated by 3 trained observers (M.K.O., M.M.H., and M.E.C.) who manually assessed information to determine a classification. The ‘Plastic Surgery’, ‘ENT Facial Plastics’, and ‘Oculoplastics’ classes were checked with data from the respective board website, each of which offered a public interface to verify certification. Accounts that no longer existed at the time of validation were excluded. Discrepancies or difficulties with classification were discussed with all authors to determine a final classification.

Performance metrics were calculated by comparing predicted categories to the independent evaluation. We calculated standard accuracy measures including Cohen’s κ test to evaluate the model.34 Our model achieved high accuracy (94.9%, class range, 87.3%-99.6%) and strong agreement between the model and independent raters (κ = 0.88; range, 0.86-0.90). High accuracy was observed for each of the provider classes (range, 94.5%-99.6%).35

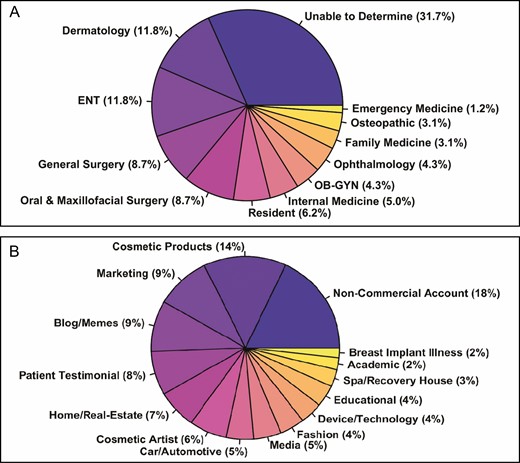

During validation, the ‘Physician’ category and the ‘Other’ category were further subclassified through manual review (Figure 2). For the ‘Physician’ category, the biographic page and linked websites associated with the validation data with the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) website were assessed.36 For the ‘Other’ category, subclassification was determined through review of the biographic page.

Subclassification of ‘Physician’ and ‘Other’ Categories. (A) ‘Physician’ category. (B) ‘Other’ category.

RESULTS

Posts, Reach, and Engagement

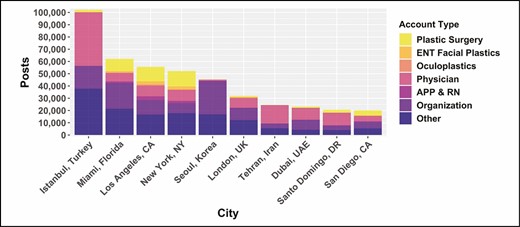

We examined 2,112,393 posts from 180,945 unique accounts between December 2018 and August 2020 (Table 1). The United States accounted for one-quarter (566,206 posts) of all posts and had the most of the 182 countries included. Non-US countries had 1,054,083 posts observed, and in 492,104 posts, no location was specified. The most prolific city was Istanbul, Turkey (102,208 posts), followed by Miami, FL (62,079 posts), Los Angeles, CA (55,667 posts), New York, NY (52,212 posts), and Seoul, South Korea (45,407 posts) (Figure 3).

| . | Total . | US . | Non-US . | Not specified . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (December 2018-August 2020) | ||||

| Posts | 2,112,393 | 566,206 | 1,054,083 | 492,104 |

| Views | 6,125,465,903 | 1,998,461,673 | 3,022,478,752 | 1,104,525,478 |

| Likes | 369,027,521 | 108,121,598 | 191,797,677 | 69,108,246 |

| Comments | 15,081,829 | 5,061,295 | 7,441,800 | 2,578,734 |

| Per day | ||||

| Posts | 3,402 | 912 | 1,697 | 792 |

| Views | 9,863,874 | 3,218,135 | 4,867,116 | 1,778,624 |

| Likes | 594,247 | 174,109 | 308,853 | 111,285 |

| Comments | 24,286 | 8,150 | 11,984 | 4,153 |

| Per post | ||||

| Views | 4,352.2 | 5,753.9 | 3,811.2 | 3,392.7 |

| Likes | 174.7 | 191 | 182 | 140.4 |

| Comments | 7.1 | 8.9 | 7.1 | 5.2 |

| Positive | 53.4% | 64.5% | 52.3% | 42.8% |

| Negative | 2.0% | 2.6% | 1.7% | 2.1% |

| Account type—number of posts (%) | ||||

| Plastic surgery | 190,540 (9.0) | 143,218 (25.3) | 39,516 (3.7) | 7,806 (1.6) |

| Facial plastics | 26,538 (1.3) | 23,697 (4.2) | 1,940 (0.2) | 901 (0.2) |

| oculoplastics | 5,202 (0.2) | 4,134 (0.7) | 832 (0.1) | 236 (0.0) |

| Non–plastic physician | 592,018 (28.0) | 75,193 (13.3) | 414,333 (39.3) | 102,492 (20.8) |

| APP & RN | 33,058 (1.6) | 26,471 (4.7) | 4,059 (0.4) | 2,528 (0.5) |

| Organization | 456,292 (21.6) | 130,585 (23.1) | 234,512 (22.2) | 91,195 (18.5) |

| Other | 808,745 (38.3) | 162,908 (28.8) | 358,891 (34.0) | 286,946 (58.3) |

| . | Total . | US . | Non-US . | Not specified . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (December 2018-August 2020) | ||||

| Posts | 2,112,393 | 566,206 | 1,054,083 | 492,104 |

| Views | 6,125,465,903 | 1,998,461,673 | 3,022,478,752 | 1,104,525,478 |

| Likes | 369,027,521 | 108,121,598 | 191,797,677 | 69,108,246 |

| Comments | 15,081,829 | 5,061,295 | 7,441,800 | 2,578,734 |

| Per day | ||||

| Posts | 3,402 | 912 | 1,697 | 792 |

| Views | 9,863,874 | 3,218,135 | 4,867,116 | 1,778,624 |

| Likes | 594,247 | 174,109 | 308,853 | 111,285 |

| Comments | 24,286 | 8,150 | 11,984 | 4,153 |

| Per post | ||||

| Views | 4,352.2 | 5,753.9 | 3,811.2 | 3,392.7 |

| Likes | 174.7 | 191 | 182 | 140.4 |

| Comments | 7.1 | 8.9 | 7.1 | 5.2 |

| Positive | 53.4% | 64.5% | 52.3% | 42.8% |

| Negative | 2.0% | 2.6% | 1.7% | 2.1% |

| Account type—number of posts (%) | ||||

| Plastic surgery | 190,540 (9.0) | 143,218 (25.3) | 39,516 (3.7) | 7,806 (1.6) |

| Facial plastics | 26,538 (1.3) | 23,697 (4.2) | 1,940 (0.2) | 901 (0.2) |

| oculoplastics | 5,202 (0.2) | 4,134 (0.7) | 832 (0.1) | 236 (0.0) |

| Non–plastic physician | 592,018 (28.0) | 75,193 (13.3) | 414,333 (39.3) | 102,492 (20.8) |

| APP & RN | 33,058 (1.6) | 26,471 (4.7) | 4,059 (0.4) | 2,528 (0.5) |

| Organization | 456,292 (21.6) | 130,585 (23.1) | 234,512 (22.2) | 91,195 (18.5) |

| Other | 808,745 (38.3) | 162,908 (28.8) | 358,891 (34.0) | 286,946 (58.3) |

APP & RN, advanced practice practitioners and registered nurses.

| . | Total . | US . | Non-US . | Not specified . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (December 2018-August 2020) | ||||

| Posts | 2,112,393 | 566,206 | 1,054,083 | 492,104 |

| Views | 6,125,465,903 | 1,998,461,673 | 3,022,478,752 | 1,104,525,478 |

| Likes | 369,027,521 | 108,121,598 | 191,797,677 | 69,108,246 |

| Comments | 15,081,829 | 5,061,295 | 7,441,800 | 2,578,734 |

| Per day | ||||

| Posts | 3,402 | 912 | 1,697 | 792 |

| Views | 9,863,874 | 3,218,135 | 4,867,116 | 1,778,624 |

| Likes | 594,247 | 174,109 | 308,853 | 111,285 |

| Comments | 24,286 | 8,150 | 11,984 | 4,153 |

| Per post | ||||

| Views | 4,352.2 | 5,753.9 | 3,811.2 | 3,392.7 |

| Likes | 174.7 | 191 | 182 | 140.4 |

| Comments | 7.1 | 8.9 | 7.1 | 5.2 |

| Positive | 53.4% | 64.5% | 52.3% | 42.8% |

| Negative | 2.0% | 2.6% | 1.7% | 2.1% |

| Account type—number of posts (%) | ||||

| Plastic surgery | 190,540 (9.0) | 143,218 (25.3) | 39,516 (3.7) | 7,806 (1.6) |

| Facial plastics | 26,538 (1.3) | 23,697 (4.2) | 1,940 (0.2) | 901 (0.2) |

| oculoplastics | 5,202 (0.2) | 4,134 (0.7) | 832 (0.1) | 236 (0.0) |

| Non–plastic physician | 592,018 (28.0) | 75,193 (13.3) | 414,333 (39.3) | 102,492 (20.8) |

| APP & RN | 33,058 (1.6) | 26,471 (4.7) | 4,059 (0.4) | 2,528 (0.5) |

| Organization | 456,292 (21.6) | 130,585 (23.1) | 234,512 (22.2) | 91,195 (18.5) |

| Other | 808,745 (38.3) | 162,908 (28.8) | 358,891 (34.0) | 286,946 (58.3) |

| . | Total . | US . | Non-US . | Not specified . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (December 2018-August 2020) | ||||

| Posts | 2,112,393 | 566,206 | 1,054,083 | 492,104 |

| Views | 6,125,465,903 | 1,998,461,673 | 3,022,478,752 | 1,104,525,478 |

| Likes | 369,027,521 | 108,121,598 | 191,797,677 | 69,108,246 |

| Comments | 15,081,829 | 5,061,295 | 7,441,800 | 2,578,734 |

| Per day | ||||

| Posts | 3,402 | 912 | 1,697 | 792 |

| Views | 9,863,874 | 3,218,135 | 4,867,116 | 1,778,624 |

| Likes | 594,247 | 174,109 | 308,853 | 111,285 |

| Comments | 24,286 | 8,150 | 11,984 | 4,153 |

| Per post | ||||

| Views | 4,352.2 | 5,753.9 | 3,811.2 | 3,392.7 |

| Likes | 174.7 | 191 | 182 | 140.4 |

| Comments | 7.1 | 8.9 | 7.1 | 5.2 |

| Positive | 53.4% | 64.5% | 52.3% | 42.8% |

| Negative | 2.0% | 2.6% | 1.7% | 2.1% |

| Account type—number of posts (%) | ||||

| Plastic surgery | 190,540 (9.0) | 143,218 (25.3) | 39,516 (3.7) | 7,806 (1.6) |

| Facial plastics | 26,538 (1.3) | 23,697 (4.2) | 1,940 (0.2) | 901 (0.2) |

| oculoplastics | 5,202 (0.2) | 4,134 (0.7) | 832 (0.1) | 236 (0.0) |

| Non–plastic physician | 592,018 (28.0) | 75,193 (13.3) | 414,333 (39.3) | 102,492 (20.8) |

| APP & RN | 33,058 (1.6) | 26,471 (4.7) | 4,059 (0.4) | 2,528 (0.5) |

| Organization | 456,292 (21.6) | 130,585 (23.1) | 234,512 (22.2) | 91,195 (18.5) |

| Other | 808,745 (38.3) | 162,908 (28.8) | 358,891 (34.0) | 286,946 (58.3) |

APP & RN, advanced practice practitioners and registered nurses.

The posts garnered more than 15 million comments, 369 million likes, and 6 billion views globally. In the United States alone, more than 100 million likes and nearly 2 billion views were observed. Sentiment scores amongst the comments were overall positive with a margin of 64.5% to 2.6% in the United States and 53.4% to 2% globally.

Account Type

In the United States, providers accounted for 48% of posts (272,713 posts, Table 1) with ‘Plastic Surgery’ as the most common (25.3%, 143,218 posts) category, followed by ‘Physician’ (13.3%, 75,193 posts), ‘APP & RN’ (4.7%, 26,471 posts), ‘ENT Facial Plastics’ (4.2%, 23,697 posts), and finally ‘Oculoplastics’ (0.7%, 4.134 posts). The ‘Other’ category accounted for the most posts of any single category with 28.8% (162,908 posts) with ‘Organizations’ accounting for the remaining posts (23.1%, 130,585 posts).

In non-US countries, providers as a group accounted for 44% of content (460,680 posts). As expected, the categories ‘Plastic Surgery’ (3.7%, 39,516), ‘ENT Facial Plastics’ (0.2%, 1940 posts), and ‘Oculoplastics’ (0.1%, 832 posts) accounted for a smaller portion of the provider category because they relied on international member surgeons of the US board organizations that defined the categories. ‘APP & RN’ also made up a smaller portion of the provider category outside of the United States (0.4% 4059 posts).

During validation, the ‘Physician’ category was subclassified through manual review (Figure 2A). Nine unique specialties accounted for 59% and included dermatology (12%), ENT (12%), general surgery (9%), oral and maxillofacial surgery (9%), internal medicine (5%), obstetrics and gynecology (4%), ophthalmology (4%), and family medicine (3.1%). Residents accounted for 6.2% of the sample, and in 31.7% of cases, board certification within an accredited specialty was unable to be determined.

For the ‘Other’ category, subclassification showed, in 18% of the sample, the accounts were noncommercial general-public accounts (Figure 2B). Posts from patients or related groups accounted for 10%. Educational accounts and academic institutions made up 6% of the sample. The remaining 66% of the sample was comprised of various commercial interests.

Tags

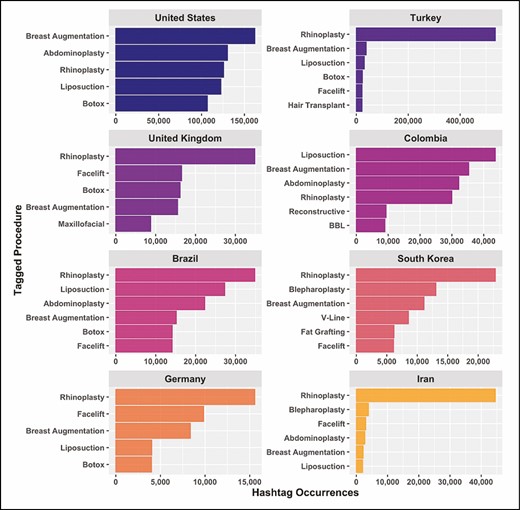

Hashtags from more than 30 languages were studied (Figure 1). For provider categories, the tag followed the most common procedures for each discipline with breast augmentation (45,099 tags) most common for ‘Plastic Surgery’, rhinoplasty (9645 tags) most common for ‘ENT Facial Plastics’, and blepharoplasty (2571 tags) most common for ‘Oculoplastics’. For ‘Physician’, the most common procedure was rhinoplasty (199,191 tags). For ‘APP & RN’ and ‘Organization’ the most common tags related to injection procedures with filler or Botox (Allergan, Inc., Irvine, CA).

Although our model was able to accurately distinguish between classes, there is significant correlation between groups regarding the tags used (Table 2). To account for variation in language and location, only posts from within the United States and in English were included to determine correlation. Tags used by plastic surgeons were highly correlated with tags used by non–plastic physicians (0.92), ‘Organizations’ (0.88), and ‘Other’ (0.81). There was also a high degree of correlation between tags used by non–plastic physicians and tags from the ‘Organization’ (0.93) and ‘Other’ (0.87) categories.

| . | Plastic Surgery . | ENT Facial Plastics . | Oculoplastics . | Physician . | APP & RN . | Organization . | Other . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Posts | 190,540 | 26,538 | 5,202 | 592,018 | 33,058 | 456,292 | 808,745 |

| Verified posts, n (%) | 5,314 (2.8) | 1,347 (5.1) | 111 (2.1) | 9,809 (1.7) | 17 (0.1) | 3,827 (0.8) | 9,060 (1.1) |

| Users | 3,537 | 427 | 149 | 23,394 | 2,205 | 20,527 | 130,719 |

| Verified users, n (%) | 44 (1.2) | 10 (2.3) | 1 (0.7) | 139 (0.6) | 4 (0.2) | 37 (0.2) | 806 (0.6) |

| Textual correlation between posts | |||||||

| Plastic Surgery | 1 | 0.71 | 0.52 | 0.92 | 0.57 | 0.88 | 0.81 |

| ENT Facial Plastics | 0.71 | 1 | 0.48 | 0.79 | 0.57 | 0.69 | 0.61 |

| Oculoplastics | 0.52 | 0.48 | 1 | 0.52 | 0.36 | 0.46 | 0.4 |

| Physician | 0.92 | 0.79 | 0.52 | 1 | 0.68 | 0.93 | 0.87 |

| APP & RN | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.36 | 0.68 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.66 |

| Organization | 0.88 | 0.69 | 0.46 | 0.93 | 0.75 | 1 | 0.92 |

| Other | 0.81 | 0.61 | 0.4 | 0.87 | 0.66 | 0.92 | 1 |

| . | Plastic Surgery . | ENT Facial Plastics . | Oculoplastics . | Physician . | APP & RN . | Organization . | Other . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Posts | 190,540 | 26,538 | 5,202 | 592,018 | 33,058 | 456,292 | 808,745 |

| Verified posts, n (%) | 5,314 (2.8) | 1,347 (5.1) | 111 (2.1) | 9,809 (1.7) | 17 (0.1) | 3,827 (0.8) | 9,060 (1.1) |

| Users | 3,537 | 427 | 149 | 23,394 | 2,205 | 20,527 | 130,719 |

| Verified users, n (%) | 44 (1.2) | 10 (2.3) | 1 (0.7) | 139 (0.6) | 4 (0.2) | 37 (0.2) | 806 (0.6) |

| Textual correlation between posts | |||||||

| Plastic Surgery | 1 | 0.71 | 0.52 | 0.92 | 0.57 | 0.88 | 0.81 |

| ENT Facial Plastics | 0.71 | 1 | 0.48 | 0.79 | 0.57 | 0.69 | 0.61 |

| Oculoplastics | 0.52 | 0.48 | 1 | 0.52 | 0.36 | 0.46 | 0.4 |

| Physician | 0.92 | 0.79 | 0.52 | 1 | 0.68 | 0.93 | 0.87 |

| APP & RN | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.36 | 0.68 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.66 |

| Organization | 0.88 | 0.69 | 0.46 | 0.93 | 0.75 | 1 | 0.92 |

| Other | 0.81 | 0.61 | 0.4 | 0.87 | 0.66 | 0.92 | 1 |

APP & RN, advanced practice practitioners and registered nurses.

| . | Plastic Surgery . | ENT Facial Plastics . | Oculoplastics . | Physician . | APP & RN . | Organization . | Other . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Posts | 190,540 | 26,538 | 5,202 | 592,018 | 33,058 | 456,292 | 808,745 |

| Verified posts, n (%) | 5,314 (2.8) | 1,347 (5.1) | 111 (2.1) | 9,809 (1.7) | 17 (0.1) | 3,827 (0.8) | 9,060 (1.1) |

| Users | 3,537 | 427 | 149 | 23,394 | 2,205 | 20,527 | 130,719 |

| Verified users, n (%) | 44 (1.2) | 10 (2.3) | 1 (0.7) | 139 (0.6) | 4 (0.2) | 37 (0.2) | 806 (0.6) |

| Textual correlation between posts | |||||||

| Plastic Surgery | 1 | 0.71 | 0.52 | 0.92 | 0.57 | 0.88 | 0.81 |

| ENT Facial Plastics | 0.71 | 1 | 0.48 | 0.79 | 0.57 | 0.69 | 0.61 |

| Oculoplastics | 0.52 | 0.48 | 1 | 0.52 | 0.36 | 0.46 | 0.4 |

| Physician | 0.92 | 0.79 | 0.52 | 1 | 0.68 | 0.93 | 0.87 |

| APP & RN | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.36 | 0.68 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.66 |

| Organization | 0.88 | 0.69 | 0.46 | 0.93 | 0.75 | 1 | 0.92 |

| Other | 0.81 | 0.61 | 0.4 | 0.87 | 0.66 | 0.92 | 1 |

| . | Plastic Surgery . | ENT Facial Plastics . | Oculoplastics . | Physician . | APP & RN . | Organization . | Other . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Posts | 190,540 | 26,538 | 5,202 | 592,018 | 33,058 | 456,292 | 808,745 |

| Verified posts, n (%) | 5,314 (2.8) | 1,347 (5.1) | 111 (2.1) | 9,809 (1.7) | 17 (0.1) | 3,827 (0.8) | 9,060 (1.1) |

| Users | 3,537 | 427 | 149 | 23,394 | 2,205 | 20,527 | 130,719 |

| Verified users, n (%) | 44 (1.2) | 10 (2.3) | 1 (0.7) | 139 (0.6) | 4 (0.2) | 37 (0.2) | 806 (0.6) |

| Textual correlation between posts | |||||||

| Plastic Surgery | 1 | 0.71 | 0.52 | 0.92 | 0.57 | 0.88 | 0.81 |

| ENT Facial Plastics | 0.71 | 1 | 0.48 | 0.79 | 0.57 | 0.69 | 0.61 |

| Oculoplastics | 0.52 | 0.48 | 1 | 0.52 | 0.36 | 0.46 | 0.4 |

| Physician | 0.92 | 0.79 | 0.52 | 1 | 0.68 | 0.93 | 0.87 |

| APP & RN | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.36 | 0.68 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.66 |

| Organization | 0.88 | 0.69 | 0.46 | 0.93 | 0.75 | 1 | 0.92 |

| Other | 0.81 | 0.61 | 0.4 | 0.87 | 0.66 | 0.92 | 1 |

APP & RN, advanced practice practitioners and registered nurses.

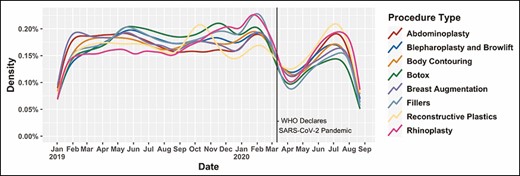

Trends for procedure-related tags over the study period are displayed in Figures 4 and 5. Trends in hashtag usage differed by region, with body contouring procedures being more common in North America and South America. In Turkey and Iran, rhinoplasty was by far the most commonly referenced procedure (Figure 4). With the onset of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, there was a sharp drop in volume of content in March and April of 2020. From May through August, content regarding ‘reconstructive plastics’ appeared to steadily recover to pre-pandemic levels. The remaining procedure categories improved but did not fully recover to pre-pandemic volume (Figure 5).

DISCUSSION

We observed trends in #PlasticSurgery content in social media from more than 2 million posts over a 21-month period. Although previous studies have sought to characterize the nature of plastic surgery content on social media platforms, they have been limited to sample sizes of fewer than 1000 posts, or accrued larger numbers by taking several small samples, often restricted to 1 region.23,37 Given the high volume of content observed in our data, such previously used sampling techniques likely captured only a portion of the daily average, making them susceptible to sampling bias. By observing the complete data, we can make all-inclusive assessments regarding the nature of content. We also predicted with high accuracy the account types associated with the content, allowing us to make comparisons at scale. Additionally, by building a multilingual dictionary of plastic surgery procedures, we were able to study content on a global scale written in more than 30 languages.

Plastic surgery content on social media has immense reach across the world, accounting for more than 2 million posts, over 369 million likes, and 6.1 billion views. We speculate that the steady growth in the number of daily posts about plastic surgery seen in 2019 and early 2020 will continue as content activity rebounds to pre-pandemic levels. Given the magnitude and extent of content throughout the world, we expect social media will serve as a major, if not primary, source of information regarding plastic surgery. This is particularly true for younger generations and suggests social media has the potential to provide education regarding the specialty and its associated procedures.

Our findings also demonstrated that content on the platform extends well beyond the United States: the most prolific city in our study was Istanbul, Turkey, with twice as many posts as any other city (Figure 3). Interestingly, over half of the posts from Turkey were classified by our model as ‘Physicians’ (49.5%) or ‘ASPS International Member Surgeons’ (1.6%). This was comparable to other international countries including France (39.6% and 0.9%, respectively) and Brazil (50.4% and 5.7%, respectively).

With regards to hashtag content, there were remarkable variations depending on the location. Longitudinal prevalence of tag content is visualized in Figure 5. The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and associated government-imposed shut-downs had a differential effect depending on the procedure. In the short term, reconstructive plastic surgery procedures appeared to rebound the quickest. Other procedures, such as abdominoplasty, body contouring, breast augmentation, and rhinoplasty, also quickly recovered to near pre-pandemic levels. However, injection procedures appear to lag behind. How these differential effects progress in the long term remains to be seen.

In our assessment of account types, there was significant variation across regions. This was expected because qualification was tied to certification with country-specific organizations. Within the United States, and in general, providers collectively accounted for 44% to 50% of content. In the United States, providers with certification from a plastic surgery–specific board made up 30.2% of all posts, and 62.7% of provider posts. On closer look within the sample of physicians in our validation sample, a wide range of specialties comprised the physician group, and a specialty could not be determined in one-third. Moreover, in our analysis of lexical diversity between account types, #PlasticSurgery usage was highly correlated with that of non–plastic physicians (0.92, Table 2). This was also true for ‘Organizations’, which demonstrated a high degree of similarity with plastic surgery accounts (0.88) and non–plastic physicians (0.93). This poses significant challenges for viewers in evaluating the source of content and presents an opportunity for misrepresentation of plastic surgery in content published by individuals and/or organizations without plastic surgery training. Recent evidence suggests unreliable information within social media platforms can be spread at the same rate, or even amplified, compared to reliable information.38,39

Considering the above trends, and as discourse continues to grow on social media platforms, the issue of verifying identity and the veracity of information could be magnified. Twitter (Twitter, San Francisco, CA) has a mechanism for verifying users but this had been paused prior to being relaunched this year.40 Instagram maintains a verification feature, but in our study only 0.57% of all users were verified and the rate ranged from 0.6% (‘Physician’) to 2.3% (‘ENT Facial Plastics’) between provider groups (Table 2). The findings suggest the feature is unlikely to be helpful in distinguishing between veritable sources.

Potential solutions to help viewers make these distinctions could include allowing plastic surgeons to link to social media accounts via the ASPS and/or ABPS website. At the time of writing, the ABPS website offers a verification feature by providing the name and address of the surgeon, but it does not provide links to websites or social media. The ASPS website via the ‘Find a Surgeon’ feature offers links to a practice website, but it does not provide a link directly to a social media account. As social media use continues to increase amongst plastic surgeons the addition of such features could help surgeons and patients alike.

Our analysis included several limitations. Although our model for classifying account types demonstrated high overall accuracy, certain class accuracies could stand to be improved, particularly for distinguishing between the ‘Other’ and ‘Organization’ categories. Additionally, the nature of social media ensures the data will continue to evolve. Although literature suggests Instagram has the strongest presence for plastic surgery regarding interactions with patients and the public, repeating the study on other platforms could also yield helpful information about the discussion on social media.

CONCLUSIONS

Plastic surgery content on social media has a profound reach, with more than 2 million posts observed over a 21-month period, accounting for more than 369 million likes and 6 billion views globally. Although the United States accounted for the most posts of 182 countries (34.9%, 566,206 posts), other regions had a significant presence on the platform including Istanbul, Turkey, which led all cities (6.3%, 102,208 posts). Whereas healthcare providers accounted for almost half of the posts studied, only 30.2% of US posts were from physicians with formal certification in a plastic surgery specialty, and only 0.5% of all posts were from verified users. We should continue to consider solutions to help social media consumers discern genuine sources of information regarding plastic surgery.

Disclosures

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Presented at: Plastic Surgery The Meeting (ASPS), October 2020.