-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Tina Tian, Yurie Sekigami, Sydney Char, Molly Bloomenthal, Jeffrey Aalberg, Lilian Chen, Abhishek Chatterjee, Assessment of Conflicts of Interest in Studies of Breast Implants and Breast Implant Mesh, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 41, Issue 11, November 2021, Pages 1269–1275, https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjab013

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

With increased collaboration between surgeons and industry, there has been a push towards improving transparency of conflicts of interest (COI).

A literature search identified all articles published between 2016 – 2018 involving breast implants/implantable mesh from three major United States plastic surgery journals. Industry payment data from 8 breast implant/implantable mesh companies was collected using the CMS Open Payments database. COI discrepancies were identified by comparing author declaration statements with payments >$100.00 found for the year of publication and year prior. Risk factors for discrepancy were determined at study and author levels.

A total of 162 studies (548 authors) were identified. 126 (78%) studies had at least one author receive undisclosed payments. 295 (54%) authors received undisclosed payments. Comparative studies were significantly more likely to have COI discrepancy than non- comparative studies (83% vs 69%, p < 0.05). Multivariate analysis showed no association between COI discrepancy and final product recommendation. Authors who accurately disclosed payments received higher payments compared to authors who did not accurately disclose payments (median $40,349 IQR 7278-190,413 vs median $1300 IQR 429-11,1544, p <0.001).

The majority of breast implant-based studies had undisclosed COIs. Comparative studies were more likely to have COI discrepancy. Authors who accurately disclosed COIs received higher payments than authors with discrepancies. This study highlights the need for increased efforts to improve the transparency of industry sponsorship for breast implant-based studies.

The relationship between industry and healthcare workers has increasingly impacted multiple realms of medicine, including research, education, and clinical practice. Industry-sponsored research in the field of plastic surgery has particularly helped foster innovation in the form of new and improved devices, products, and techniques. However, an ethical dilemma presents itself in industry-sponsored research when the physician is provided financial compensation. This compensation can be direct in the form of consultant fees or indirect through food and beverage, hotel costs, honoraria, etc. A systematic review comparing industry-sponsored research with similar non-funded studies showed that the former was more likely to favor pharmaceutical treatment.1 Several studies have shown that clinical practice patterns can be affected by industry sponsorship even when physicians deny any influence.2 A study conducted by Wazana et al discovered that physicians who attended industry-funded educational events and accepted funding for travel/lodging were more likely to support the industry sponsor’s pharmaceutical treatments.3

Financial conflicts of interest in plastic surgery have come under considerable scrutiny for concerns that it may influence patient care. A systematic review of the plastic surgery literature demonstrated that only a small proportion of publications are dedicated to evaluating ethical principles despite the extensive number of ethical issues that plastic surgeons often face.4 Lopez et al reviewed a year’s worth of plastic surgery publications and concluded that investigators with a financial conflict of interest (COI) were significantly more likely to publish positive conclusions compared with their non-funded counterparts.5 A review of abdominal wall reconstruction literature performed by DeGeorge et al revealed that studies reporting a COI with acellular dermal matrix companies were more likely to endorse the use of these products.6 A recent survey of 322 members of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons showed that the majority have a history of accepting industry gifts but refute their influence on personal clinical practice.7

In response to the increased concern for potential industry-influenced biases, the Physician Payments Sunshine Act was proposed under the 2010 Affordable Care Act and fully implemented in January 2017.8 This federal law requires all industry manufacturers to report all payments made to physicians. This information became publicly available in 2015 with the launch of the Open Payments Database website (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), Baltimore, MD; openpaymentsdata.cms.gov). A recent study by Boyll et al demonstrated that 87% of authors had a discrepancy between the Open Payments database and author self-disclosure on plastic surgery pubications.9

The aims of this study were to identify studies related to breast implant and implantable mesh published in 3 major plastic surgery journals in order to (1) evaluate the accuracy of reporting of financial COI and (2) determine if any risk factors are significantly associated with COI discrepancy.

METHODS

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Open Payments Program was utilized to evaluate the accuracy of industry payment disclosures for breast implant and implantable mesh studies. We looked at studies published between January 2016 and December 2018 to ensure all author payments would be reported in the database, which currently includes payment data from January 2013 to December 2018.

Study Selection and Search

A literature search conducted by a single author (T.T.) in December 2019 employing MEDLINE (National Center for Biotechnology Information [NCBI], Bethesda, MD) and EMBASE (Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) identified articles published between January 2016 and December 2018 involving breast implants and/or implantable mesh from 3 US-based plastic surgery journals with the highest impact factors (Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Annals of Plastic Surgery, and Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery). Search terms were as follows: “breast implant,” “breast reconstruction,” “breast augmentation,” “augmentation mastopexy,” “implant-associated lymphoma,” “pre-pectoral,” “sub-pectoral,” “implantable mesh,” “tissue expander,” and “acellular dermal matrix.” Only studies written in English and those with at least 1 US author were included. Abstracts, conference reports, and studies solely focusing on autologous reconstruction were excluded.

Payment Data

Author payments were identified by 4 authors in January 2020 (T.T., Y.S., S.C., M.B.) utilizing the Open Payments database. Payment data from the 8 major companies with commercially available and FDA-approved breast implant and implantable mesh products (Allergan/LifeCell [Irvine, CA], Mentor [Santa Barbara, CA], Sientra [Santa Barbara, CA], Integra [Plainsboro Township, NJ], Ethicon [Bridgewater, NJ], Johnson & Johnson [New Brunswick, NJ], Musculoskeletal Transplant Foundation [Edison, NJ], and Bard [Franklin Lakes, NJ]) were collected from both the year of study acceptance and the year prior (24-month period). We included any payment that was categorized as a “general payment” and totaled greater than $100 over the 24-month period. These payments included consulting fees, food and beverage, royalties, licensing, gifts, honoraria, travel and lodging, and speaking or educational fees.

Study and Author Data

Study information was collected employing a standardized protocol. The following data were extracted from each study: authors, journal name, publication date, acceptance date, impact factor, study type, presence or absence of a declaration statement, number of authors, and whether the study was in support of breast implants or implantable mesh. Authors were categorized as first, middle, or last author. The total cumulative payments for all authors were then recorded as total payments received for each study. Study types were further characterized into comparative (randomized controlled trials, retrospective cohort, etc) vs non-comparative (editorials, medical education articles, case reports, etc). Data collection was reviewed by 2 authors (T.T., Y.S.). Differences in data collection were reviewed in further detail by the senior author (A.C.) to reach a consensus.

Outcomes

If an author received any payment from the 8 major breast implant/implantable mesh companies totaling greater than $100 in the 24-month period prior to study acceptance, this was considered to be a COI for both the author and the study. This 24-month period time interval was felt to be reasonable based on past publications on what constituted an “expiration” time limit for a COI.10,11 Payments received from companies other than the 8 listed were not considered for the purpose of this analysis.

At the author level, we defined a discrepancy as receipt of any payment as detailed above that was not disclosed in the declaration statement. At the study level, we considered a discrepancy to exist if any of the study authors did not disclose a payment. Finally, we evaluated whether breast implants or implantable mesh was recommended based on the study conclusions.

Recommendations were classified with respect to study outcome: (1) positive, (2) negative, or (3) neutral. A positive outcome was defined as any study that recommended utilization of the product or stated that the product was superior or equivalent to the standard of care. A negative outcome was defined as any study that explicitly recommended against utilizing the product, reported that the product was unsafe, or stated that the product was inferior to the standard of care. A neutral study was defined as the authors providing no recommendation regarding the product. Studies that compared different types of implants or implantable mesh were also considered neutral.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed by 1 of the authors (J.A.) employing SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Univariate associations were determined utilizing chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables. The Bonferroni method was employed to correct for multiple comparisons when examining differences between payment levels. Logistic regression was utilized to determine associations in a multivariate setting and associations reported as odds ratios. All variables in the multivariate analysis were chosen by the researchers; no selection process was utilized. The alpha level was set at 0.05 (2-tailed) for all tests.

RESULTS

After performing a literature search utilizing MEDLINE and EMBASE, 4121 studies were identified. After removing studies that had no US authors, 1086 studies were assessed for inclusion. A total of 177 studies met our inclusion criteria, which included 590 authors (Table 1).

| Characteristic . | Value (%) . |

|---|---|

| Study design | |

| Comparative | 119 (67) |

| Non-comparative | 58 (33) |

| Declaration statement present | 177 (100) |

| Article stance | |

| Positive | 56 (32) |

| Neutral | 106 (60) |

| Negative | 15 (8) |

| No. of authors (mean) | 3.46 |

| Topic | |

| Breast implant | 74 (42) |

| Implantable mesh | 36 (20) |

| Both | 67 (38) |

| Journal | |

| Aesthetic Surgery Journal | 37 (21) |

| Annals of Plastic Surgery | 37 (21) |

| Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery | 103 (58) |

| Characteristic . | Value (%) . |

|---|---|

| Study design | |

| Comparative | 119 (67) |

| Non-comparative | 58 (33) |

| Declaration statement present | 177 (100) |

| Article stance | |

| Positive | 56 (32) |

| Neutral | 106 (60) |

| Negative | 15 (8) |

| No. of authors (mean) | 3.46 |

| Topic | |

| Breast implant | 74 (42) |

| Implantable mesh | 36 (20) |

| Both | 67 (38) |

| Journal | |

| Aesthetic Surgery Journal | 37 (21) |

| Annals of Plastic Surgery | 37 (21) |

| Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery | 103 (58) |

| Characteristic . | Value (%) . |

|---|---|

| Study design | |

| Comparative | 119 (67) |

| Non-comparative | 58 (33) |

| Declaration statement present | 177 (100) |

| Article stance | |

| Positive | 56 (32) |

| Neutral | 106 (60) |

| Negative | 15 (8) |

| No. of authors (mean) | 3.46 |

| Topic | |

| Breast implant | 74 (42) |

| Implantable mesh | 36 (20) |

| Both | 67 (38) |

| Journal | |

| Aesthetic Surgery Journal | 37 (21) |

| Annals of Plastic Surgery | 37 (21) |

| Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery | 103 (58) |

| Characteristic . | Value (%) . |

|---|---|

| Study design | |

| Comparative | 119 (67) |

| Non-comparative | 58 (33) |

| Declaration statement present | 177 (100) |

| Article stance | |

| Positive | 56 (32) |

| Neutral | 106 (60) |

| Negative | 15 (8) |

| No. of authors (mean) | 3.46 |

| Topic | |

| Breast implant | 74 (42) |

| Implantable mesh | 36 (20) |

| Both | 67 (38) |

| Journal | |

| Aesthetic Surgery Journal | 37 (21) |

| Annals of Plastic Surgery | 37 (21) |

| Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery | 103 (58) |

Study-Level Results

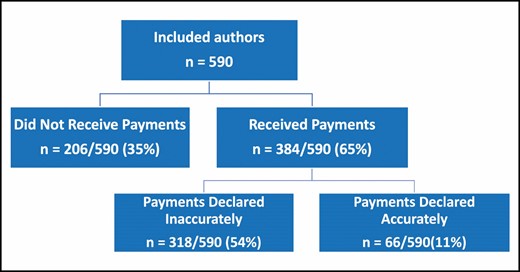

Of the 177 included studies, all had a declaration statement present. A total of 159 (90%) studies had at least 1 author receive a payment from industry (Figure 1), and 141 (80%) studies had at least 1 author receive payments from industry and did not accurately disclose them. The average journal impact factor was 3.48. Fifty-six (32%) studies had a positive final recommendation, 106 (60%) studies were neutral, and 15 (8%) studies had a negative recommendation. One-hundred nineteen (67%) studies were of comparative type. For studies with authors receiving payments, the cumulative amount over a 24-month period ranged from a minimum of $101 to maximum of $10,010,816.

Author-Level Results

Of the 590 authors, 384 (65%) received payments (Figure 2). Three-hundred eighteen (54%) of the authors who received payments did not accurately disclose their payments. The average number of authors per study was 3.46. The top 3 companies with discrepancies were Allergan/Lifecell, Sientra, and Mentor.

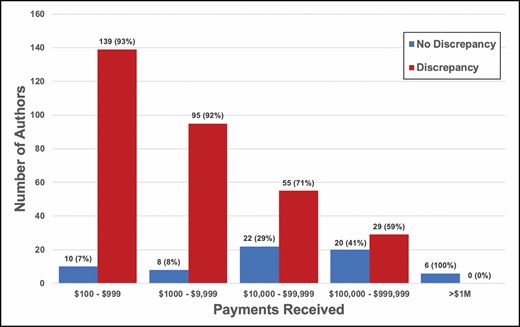

The total amount of payments received per author ranged from a minimum of $101.04 to maximum of $9,466,803. Authors who accurately disclosed payments had higher payments received compared with authors who did not accurately disclose payments (median $58,013 IQR $9810 to $332,312 vs median $1291 IQR $386 to $11,154, P < 0.0001). The top 3 payments received were $9,466,803, $9,333,499, and $4,617,266. Of authors who accurately disclosed payments, 10 (7%) received $100 to $999, 8 (8%) received $1000 to $9999, 22 authors (29%) received $10,000 to $99,999, 20 (41%) received $100,000-$999,999, and 6 (100%) received >$1 million. Of authors who did not accurately disclose payments, 139 authors (93%) received $100 to $999, 95 authors (92%) received $1000 to $9999, 55 authors (71%) received $10,000 to $99,999, 29 authors (59%) received $100,000 to $999,999, and 0 (0%) received >$1 million (P < 0.05 for all comparisons within a payment level) (Figure 3).

Predictors of Discrepancy

At the study level, on univariate analysis, comparative studies were significantly more likely to have a COI discrepancy than non-comparative studies (84% vs 71%, P < 0.05). Author order was not significantly associated with an increased risk of discrepancy. Of the 177 studies, 56 studies had a positive stance towards the utilization of implants or mesh based on our aforementioned criteria. Multivariate analysis showed no significant association between COI discrepancy and final stance of the publication as positive, negative, or neutral towards the utilization of implant/mesh.

No predictors of COI discrepancy were identified at the author level in either univariate or multivariate analyses.

DISCUSSION

With the increase in industry sponsorship in various aspects of healthcare, there also comes increased concern for how this may impact the integrity of clinical research results. With the almost necessary utilization of industry products for plastic and reconstructive surgery, some may argue that this collaboration with industry becomes essential. The senior authors in this study have had multiple collaborative efforts with industry and see this as essential to help guide the development and evaluation of the next generation of surgical tools. Furthermore, individuals with COI often have the most experience with certain devices given their thorough involvement in the early development and trials of a product.12 Nevertheless, such relationships must be declared when educating others through research publications and continuing medical education events.

The relationships between industry and physicians have been reported as high as 94%, which include receiving food in the workplace, free pharmaceutical/device samples, reimbursement costs for attending professional meetings, consultant fees, etc.13 A recent study demonstrated a total of $5,278,613 received by 4195 plastic surgeons over a 5-month period.14 Without accurate declarations of COI, the integrity of the plastic surgery profession comes into question and exposes surgeons to criticism that can be quickly sensationalized by the media. A review of the editors-in-chief of the top 100 surgery journals found an average payment of $3307, with the majority of editors-in-chief receiving less than the average of other physicians within their own specialty.15

The Physician Payment Sunshine Act is the first federal effort to bring greater transparency to the relationships between physicians and industry. Furthermore, the majority of major plastic surgery journals require disclosures of COI for consideration of publication. The large percentage of discrepancies seen in our study results may be the result of several factors. First, there may be some confusion among authors as to what can be considered a COI.16 Although a certain financial compensation may not be considered relevant by the author, it could create a biased effect on the study results. Furthermore, COI disclosure forms vary widely across journals and may benefit from a standardization process. A recent study by Ziai et al proposes minimizing author error by requiring a reporting of all financial ties, with relevant disclosures determined by an unbiased third party.17 Another study proposed that with improvements in the Open Payments Database, this can now be utilized by journals to characterize and verify financial disclosures by investigators during the review process.18 Recent guidelines from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons set $100 as the starting amount of what needs to be reported.19 The Aesthetic Society requires the disclosure timeframe to include the current month and preceding 12 months.20

This approach employing the Open Payments Database is favored by the authors of this paper given the universal access and transparency of the database. As a program of the federal government, this database is an accountable and verifiable source if any questions arise regarding a COI not reported. We propose that authors for any submission should commit (per submission requirement by the journal being submitted to) to checking the Open Payments Database and report what is present in that database. This approach relieves the burden to the journal of checking every author and encourages all authors to know what is being reported to the Open Payments Database (which they can appeal if inaccurate). We acknowledge that this method would be limited to US authors at this time because the database currently tracks only US physicians.

It is unclear at this point whether all types of financial conflicts have the same amount of impact on clinical care. In a survey of plastic surgeons of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, the majority of surgeons did not consider all types of COIs to be equally influential on provider behavior, with the most influential forms considered as being an employee of the company and receiving royalties or owning stock.7 Our results show an increasingly higher COI discrepancy rate with smaller payments, with only 7% of authors accurately disclosing payments between $100 and $999. There are several potential hypotheses to explain this inverse correlation. Boyll et al theorized that discrepancies in payment disclosures do not suggest “nefarious intent” but are more likely to be secondary to confusion regarding what is relevant and necessary for disclosure.9 Many physicians may be unaware that all rebates for utilization of products, participating in a company’s rewards program, or attending a reception where they must sign in all count towards the Open Payments Database. Much of what is listed in this database is not in the form of cash payments but instead as hidden payments. One can argue that this is very different from receiving thousands of dollars in the form of consulting fees.

Our study is not without limitations. A major limitation to our study is the subjective nature of our classification of studies as positive, negative, or neutral toward the utilization of implants/mesh. Similar to the methodology conducted in previous studies, we created strict definitions for each classification and reviewed all articles in duplicate to reach consensus.5,21 Although our study results demonstrated a trend towards positive outcomes with COI discrepancy, this was not statistically significant. Although this may potentially be attributable to our limited sample size and 3-year study period, further studies will be needed to determine if this relationship is truly statistically significant.

Our analysis was also limited in that we evaluated only 3 journals. However, these journals each have excellent reputations and high impact factors and strive for ethical excellence, which is why such a high rate of undisclosed payments is so alarming. It is reasonable to assume that if these journals have such high rates, then other journals may have similarly high rates of undeclared reporting. Furthermore, by targeting only the 8 major industry companies, these results do not reflect any payments by smaller companies not included that may also provide significant financial compensation to plastic surgeons. Our study is also limited by any potential inaccuracies in reporting to the Open Payments Database. Nevertheless, this database is currently the only nationally publicly available database to confirm financial compensation. A further limitation is the evaluation criteria employed. We chose >$100 as a significant amount of financial funding to be considered in this study, which we acknowledge is an arbitrary criterion.

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings demonstrate a significant discrepancy between disclosed COI and actual financial compensation received at both the author and study levels. This study demonstrates that there are still many improvements to be made in providing increased transparency for industry-funded plastic surgery research. Further investigation is warranted to explore interventions that may improve the accuracy of reporting prior to study publication.

Disclosures

In support of the findings within this study, the physician authors queried their own data using the Open Payments database and voluntarily disclose all identified industry payments.

Dr Tian has received payments from KCI (St. Paul, MN). Dr Sekigami has received payments from Biom'Up SA (Lyon, France). Dr Chatterjee has received payments from KCI (St. Paul, MN), Molnlycke Health Care (Gothenburg, Sweden), Biom'Up SA (Lyon, France), Focal Therapeutics (Aliso Viejo, CA), PolarityTE (Salt Lake City, UT), MedTronic (Dublin, Ireland), Gore (Newark, DE), Allergan (Irvine, CA), Mentor (Irvine, CA), Ethicon (Bridgewater, NJ), and Smith+Nephew (Watford, United Kingdom). Dr Chen has received payments from Allergan, Ethicon, Applied Medical Resources Corporation (Rancho Santa Margarita, CA), and Smith+Nephew (Watford, United Kingdom). The other authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

REFERENCES

American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery.

American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons.