-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Ryan D Wagner, Kristy L Hamilton, Andres F Doval, Aldona J Spiegel, How to Maximize Aesthetics in Autologous Breast Reconstruction, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 40, Issue Supplement_2, December 2020, Pages S45–S54, https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjaa223

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

With continuous technical and functional advances in the field of breast reconstruction, there is now a greater focus on the artistry and aesthetic aspects of autologous reconstruction. Whereas once surgeons were most concerned with flap survival and vessel patency, they are now dedicated to reconstructing a similarly or even more aesthetically pleasing breast than before tumor resection. We discuss the approach to shaping the breast through the footprint, conus, and skin envelope. We then discuss how donor site aesthetics can be optimized through flap design, scar management, and umbilical positioning. Each patient has a different perception of their ideal breast appearance, and through conversation and counseling, realistic goals can be set to reach optimal aesthetic outcomes in breast reconstruction.

Continuous advances in autologous breast reconstruction have resulted in the establishment of deep inferior epigastric perforator (DIEP) flap breast reconstruction as the standard of care at some institutions.1,2 More than 4 decades ago, the pedicled transverse rectus abdominus myocutaneous flap was the first utilized option for abdominal-based reconstruction, which evolved into the free transverse rectus abdominus myocutaneous flap with the advent of microsurgery, then finally to the more technically demanding muscle-preserving DIEP flap.2 Numerous recent technical innovations have improved free flap survival, streamlined perforator selection, and optimized reliability and efficiency in microsurgical breast reconstruction. Although much of the recent literature has focused on these technical aspects, plastic surgeons are concurrently making significant advancements in the aesthetic aspects of breast reconstruction. This review will discuss refinements in flap design, inset, and shaping to enhance breast aesthetics as well as abdominal donor site optimization to improve abdominal appearance. The institutional review board from Houston Methodist Hospital granted approval of this research protocol (institutional review board no. Pro00011704).

Aesthetic improvements are often viewed as artistic in nature. Some surgeons see these elements as difficult to teach or describe, and some trainees view them as challenging to learn or reproduce.3,4 However, basic principles can be applied to both the analysis of the defect or deformity and the reconstruction to maximize the aesthetics. It is important to determine the patient’s expectations and goals for their reconstruction. Often, patients have their own ideal of what is aesthetically optimal, and this ideal may vary from one patient to another. Further, what the patient identifies as their ideal breast image may not be concordant with that of the surgeon. It is not infrequent that the surgeon is unsatisfied with the final outcome of a reconstruction with which the patient is very satisfied, or vice versa. Some patients may wish the volume, shape, and ptosis of their current breasts to be retained, while others may desire their breasts to be smaller, larger, more projecting, or lifted. Each patient has a different perception of what is ideal, and the surgeon must elicit the patient’s preferences but also inform the patient of what can realistically be achieved through reconstruction. In this way, the surgeon and patient can develop a mutually agreed on reconstructive goal and set expectations to optimize aesthetics in the reconstruction.

THE BREAST

Footprint

Some aspects of breast reconstruction are largely out of the control of the plastic surgeon, including the mastectomy, need for radiation, and individual patient factors. However, with a systematic approach to analysis, planning, and reconstruction, an aesthetically pleasing outcome can be achieved in both routine and complex cases. Blondeel et al described a useful 3-step model for shaping the breast, which considers the breast footprint, conus, and skin envelope.3,5,6 The footprint is the foundation of the breast. The anatomic borders include a curved contour just below the clavicle superiorly, the lateral border of the sternum medially, the inframammary fold (IMF) inferiorly, and the mid-axillary line laterally.3,7 In aesthetic breast surgeries such as augmentations, the breast footprint is already set. However, in breast reconstruction, the footprint often needs to be reestablished after mastectomy.4,5 This offers the plastic surgeon an opportunity to make changes to the footprint if needed. For example, if the breasts are asymmetric or particularly narrow or wide, control of the footprint can optimize the final aesthetic result.

In delayed reconstruction, the footprint often needs to be completely recreated. Occasionally, patients in this subgroup have undergone radiation treatment, which makes the remaining mastectomy skin less pliable. This is particularly important to consider when assessing the skin inferior to the mastectomy scar, which usually needs to be excised to recreate a natural lower pole for the flap reconstruction. The senior author (A.J.S.) pays particular attention to determining the location of the IMF. During preoperative markings, it should be marked higher than expected because removal of the lower tissue often displaces the fold inferiorly. This is magnified by radiation and the pulling force generated by the abdominal closure.3,8 It is easier to lower a fold during a secondary operation than pull it superiorly because the latter requires abdominal skin advancement and suture fixation.

In immediate reconstruction, the first step is to reestablish and reinforce the IMF after the mastectomy. The lateral border and the IMF can be rebuilt by suturing the mastectomy flaps back down to the chest wall, carefully avoiding the endings of the lateral intercostal nerves that are located at the edge of the pectoralis and can cause painful neuromas if caught in a suture. To improve symmetry, it is important to note and mark any discrepancies in the heights of the IMFs before the operation.

Conus

After the footprint has been established, the flap must be inset and shaped. This process will determine the conus of the breast, defined as the shape, projection, and volume. In unilateral reconstructions, the entire abdomen is harvested and zone 4 or zones 3 and 4 are trimmed to match the volume of the contralateral breast.5 It is prudent to leave the flap volume slightly larger than ultimately desired because the flap may need to be sculpted on a secondary revision or the patient may lose weight after completing their breast reconstruction journey. Alternatively, for patients with minimal abdominal tissue or insufficient abdominal volume to match the contralateral breast, the senior author utilizes a stacked or double-pedicled DIEP flap with an intra-flap anastomosis. This procedure allows the entire abdomen to be utilized while ensuring adequate perfusion to both hemiabdomens.9,10 The flap can be shaped in a variety of ways. A small wedge of tissue can be excised at the umbilicus and the 2 edges of the flap sutured together to create a 3-dimensional shape. Another approach is to fold in the lateral edges of the flap to build more projection. The senior author does not utilize immediate implants to increase projection. The need for an additional implant is evaluated after the flap has settled and symmetry is assessed in preparation for the secondary revisional surgery. Methods for inset vary depending on the breast pocket and the timing of the reconstruction. In delayed reconstruction, the breast pocket is recreated and can hold the flap in position with little need for additional suspension (Video 1). In immediate reconstruction, the pocket is often too large for the flap, and some surgeons advocate for the fixation of the flap employing key sutures. These sutures can prevent the flap from falling laterally and help improve the superomedial fullness, which is a difficult region to define.4,5,7

In bilateral reconstruction there is less opportunity to tailor flap volume. During flap harvest, the senior author bevels the dissection superiorly and laterally to capture additional tissue if additional volume is desired, but gains are substantial.8 There are differing opinions on flap inset in bilateral cases. The senior author advocates for the flap to be inset ipsilaterally and rotated 180 degrees with the medial aspect of the flap positioned laterally on the breast. This approach offers several advantages: the superficial vein is positioned close to the internal mammary vein and the DIEP pedicle, permitting quick anastomosis if additional venous drainage is required, and the T12 intercostal sensory nerve branches of the flap can easily reach the anterior branches of the T3 intercostal nerve in the same microsurgical field if neurotization is desired.11,12 Other surgeons prefer to rotate the flap 90 degrees and position the lateral aspect of the flap superiorly on the breast to place the thicker medial abdominal tissue on the inferior pole where more volume is needed. Alternatively, others prefer to position the flap contralaterally on the chest to optimize positioning of the pedicle. Regardless of the method of flap inset, it is often helpful to sit the patient up to 45 degrees prior to final inset to better assess the position, projection, and symmetry of the breasts.4,5,13

Envelope

The next consideration is the envelope of skin and subcutaneous tissue, which, together with the conus, determines the shape of the breast. The envelope is initially influenced by the type and manner in which the mastectomy performed. Skin-sparing and nipple-sparing mastectomy (NSM) techniques are now performed routinely in the appropriate patient population. This preservation of the native skin envelope of the breast subsequently allows for a more natural reconstruction. When the nipple-areola complex can be preserved, the entire breast envelope can often be left intact with a single scar adjacent to the areola or, preferably, within the IMF.2,4 NSM has been shown to be an oncologically safe operation, and reconstruction after NSM is associated with high patient satisfaction and a low complication profile.14-17 Until recently, the ideal candidate for NSM was a patient with little to no ptosis, relatively small breasts, and a body mass index of less than 30 and who was a nonsmoker.2,18 However, this population has expanded with the introduction of new techniques such as a staged reduction or mastopexy in patients undergoing prophylactic mastectomy.19,20 Salibian et al showed that staged breast reduction an average of 5 months prior to mastectomy significantly reduced the incidence of major mastectomy flap necrosis. However, no significant difference in nipple-areola necrosis rate was found between staged and nonstaged techniques (Supplemental Figure 1).18

Skin quality and availability differ vastly between immediate and delayed reconstruction. In delayed reconstruction, there is often a shortage of available skin and the skin may be retracted or scarred. When dissecting the breast pocket, it is imperative to release any bands or constrictions to allow the envelope to fully expand.3,5 After mastectomy, the skin flaps tend to fall laterally where they can scar in place if an expander was not inserted in a delayed-immediate fashion. The lateral breast pocket is a key area to examine when releasing scar bands and areas of fibrosis. Once inset, the flap should not feel compressed because of a scarred skin envelope. Resecting severely scarred breast skin is always an option as more abdominal tissue can be employed to establish the envelope. The contralateral breast should be closely considered at this stage to determine whether reduction or mastopexy may be required in the future or whether the patient is happy with the current appearance of her contralateral breast. Ptosis can be increased by recruiting additional abdominal skin or reduced by removing a larger portion of this skin and tightening the envelope.7 A final consideration is the design and inset of the abdominal skin paddle. A smaller skin paddle ellipse can be designed and positioned within the mastectomy scar in the center of the breast mound to create 2 aesthetic units. Alternatively, all the skin inferior to the mastectomy scar can be excised or deepithelialized, with the skin paddle extending from the mastectomy scar to the IMF to create the appearance of a single aesthetic unit. The latter design, advocated by the senior author, can lead to a more natural transition from the native breast envelope to the reconstructed envelope and better positioning of the IMF.7

By contrast, in immediate reconstruction, there is rarely a paucity of skin when the mastectomy flaps are healthy and well perfused. Because it is important to have a well-tailored skin envelope without significant redundancy, the contralateral breast needs to be considered to assess whether resection of excess skin is necessary. Resecting excess breast skin can complement the conus of the flap and prevent early ptosis of the reconstructed breast.4,5 If significant ptosis is present, a staged mastopexy can be considered, as discussed above. Alternatively, the mastectomy can be planned with a vertical incision or a wise-pattern incision with a bipedicle dermal flap to preserve the nipple if additional skin reduction is required.20,21 However, it is important to note that, as in any breast-shaping procedure, the main focus should be on reshaping the gland, or in this case the flap, so that the skin drapes over the underlying form. The skin itself should not be utilized to shape the breast because this will not produce a long-lasting result. The skin stretches and conforms to the underlying tissue (Figure 1; Supplemental Figure 2).

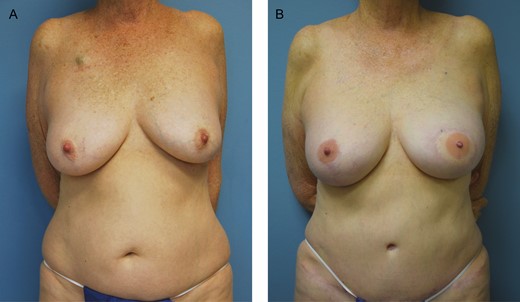

(A) Preoperative photograph of this 51-year-old female with right breast cancer who underwent right mastectomy and immediate right deep inferior epigastric perforator flap breast reconstruction followed by a left mastopexy and a right breast flap revision for symmetry. (B) The final photograph displays her 10-month postoperative result.

General Considerations

Postoperative radiation prior to reconstruction is another important aesthetic consideration. Opinions differ regarding the optimal time to perform autologous reconstruction on patients receiving radiation treatment, but many surgeons, including the senior author, prefer to delay reconstruction until after radiation is completed because of the negative effects of radiation on the tissues. Radiation can lead to poor skin quality, fibrosis, fat necrosis, and contraction of tissues.9,22,23 In addition, the aesthetic deformities that result from radiation are often difficult to correct in a subsequent revision. Many variables can affect the final reconstructive outcome, including the timing, duration, and dose of the radiation. Some studies have demonstrated a negative impact of radiation on aesthetic outcomes and patient satisfaction, while others are inconclusive.22-25 In some instances, it is unknown whether the patient will require radiation until after the surgical pathology has returned. Some surgeons advise delayed-immediate reconstruction in such cases to preserve the skin envelope and avoid the adverse effects of radiation on the reconstructed breast. Several studies have shown improved aesthetic outcomes employing this technique compared with traditional delayed reconstruction.26,27 However, these improved outcomes must be weighed against the higher rate of complications associated with immediate reconstruction and radiation therapy. The timing of reconstruction should ultimately be decided by mutual agreement between the patient and the surgeon based on the patient’s reconstructive goals (Figure 2; Supplemental Figure 3).

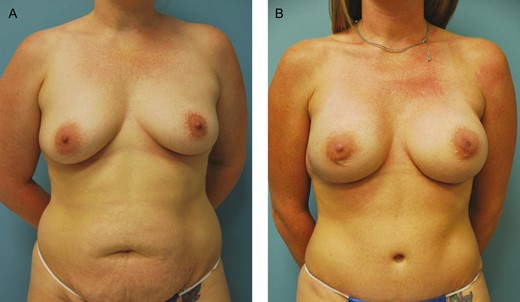

(A) Preoperative photograph of this 63-year-old female with left breast cancer who underwent left mastectomy and tissue expander placement followed by radiation therapy. She then underwent a delayed neurotized stacked deep inferior epigastric perforator flap reconstruction followed by a left breast flap revision and right mastopexy for symmetry. (B) The final photograph displays her 11-month postoperative result.

Symmetry is an important consideration during the initial free-tissue transfer. However, refinements are generally pursued during a secondary revisional surgery. Asymmetry after initial reconstruction is more common after delayed reconstructions and unilateral reconstructions. In delayed reconstructions, the scarring can distort the normal anatomy of the breast, and this effect is magnified when radiation is employed.28,29 The decision on how to approach a symmetry procedure for unilateral reconstruction should be based on the pre-mastectomy appearance of the breast, the type of mastectomy and reconstruction performed, and the patient’s reconstructive goals. The procedure can be performed on the reconstructed breast or the contralateral breast. On examination of the reconstructed breast, volume can be selectively removed or repositioned by direct excision, reduction mammaplasty, mastopexy, or liposuction. There are no specific guidelines in the literature on when the procedure should be performed. However, it is generally recommended to wait at least 3 months to avoid compromising long-term flap survival.28,30 Although slightly more challenging, volume can also be added to the reconstructed breast through fat grafting or implant augmentation. Despite the complications associated with fat grafting, including fat necrosis, numerous clinical studies have established its oncologic safety and it is routinely performed by the senior author.12,31-33 The most common symmetry procedures for the contralateral breast are implant augmentation, reduction, and mastopexy (Figure 3).29,34 Although these procedures can be performed at the time of reconstruction, they are usually delayed to determine how the flap will settle in terms of location on the chest wall, shape, and volume (Video 2).

(A) Preoperative photograph of this 31-year-old female with a strong family history of breast cancer and a positive BRCA mutation who underwent bilateral mastectomies and immediate bilateral deep inferior epigastric perforator flap reconstruction followed by a bilateral breast flap revision and bilateral implant placement for additional volume and projection. (B) The final photograph displays her 1-year postoperative result.

THE ABDOMEN

The goal for the abdominal donor site is to optimize aesthetics and, where possible, approximate the result of an abdominoplasty. Just as DIEP flap breast reconstruction increasingly parallels cosmetic breast surgery in terms of desired results, the donor site must similarly achieve a successful aesthetic result; otherwise, the surgeon sacrifices the appearance of one part of the body to create an aesthetic result elsewhere. Nonetheless, the guiding focus of the flap harvest should be to ensure a flap of adequate size and viability for breast reconstruction. Thus, a successful flap design for each patient dictates what is achievable for the abdominal donor site in terms of scar location. Optimization of the umbilical location relative to the proportions of the torso can also enhance the appearance of the donor site. Finally, the method of wound closure and abdominal sculpting influences the outcome.

Flap Design

The major reasons for dissatisfaction with the donor site after DIEP flap breast reconstruction include bulging tissue at the lateral aspects of the incision or standing cone deformities, residual abdominal overhang, discrepancies in the abdominal wall thickness above and below the scar, and the scar location.35 In the majority of cases, the periumbilical perforators are incorporated into the DIEP flap because they are usually the most robust and reliably present.36,37 In some patients with a significant excess of abdominal tissue who otherwise could be considered candidates for standard abdominoplasty, the scar can still be positioned low on the abdomen without leading to problems with closure. However, in patients with less abdominal laxity, a flap design that includes the umbilicus has traditionally necessitated a higher and, therefore, more visibly unappealing scar. Alternative DIEP flap designs have been proposed to combat this problem, including the low DIEP flap for reconstruction of small to moderate-sized breasts and the mini-DIEP flap for partial breast reconstruction as previously published by the senior author.36,38,39 For the low DIEP flap, preoperative planning with routine computed tomography or magnetic resonance angiography of the abdomen allows the DIEP flap to be marked with a smaller vertical width and lower on the abdomen as long as a dominant perforator is present 4 cm inferior to the umbilicus.36 The inferior border of the abdominal scar can thus be lowered to just above the pelvic rim so that it is hidden in the underwear line of the patient, approximating the scar of a mini-abdominoplasty.36,40 As an added benefit, this flap design often eliminates the need to recreate the umbilicus.

The need for revision surgery for deformities including standing cones is far lower after abdominoplasty than after DIEP flap breast reconstruction.35,41 Therefore, standing cones should be curtailed as much as possible during the initial operation to minimize the need for revisions and strive to achieve the aesthetic goals of reconstruction. The abdominal incision should be closed lateral to medial.35 The incision can be extended slightly if necessary during the initial operation to remove excess skin and fat. However, the area at the lateral aspects of the incision can be utilized later as a reservoir for fat grafting and refined during the symmetry stage to improve the abdominal contour.

Umbilical Positioning

Prior to final closure, the abdominal incision can be tailor-tacked with staples to optimize the symmetry and plan the ideal placement of the umbilicus. The abdominal midline should be marked preoperatively to insure proper horizontal positioning. Taking into account the proportions of the abdomen, the umbilicus should be placed along this midline either at the level of the anterior superior iliac crest or at a pre-set position along the xiphoid to the pubic symphysis.42 Although a slightly superior placement yields a more “athletic” look, some surgeons maintain that placing the umbilicus 2 cm below the original achieves the most natural appearance.43 Visconti et al proposed basing the placement of the umbilicus on the golden ratio (1.62) of the abdominal aesthetic unit, which is defined as xiphoid-umbilicus to umbilicus-abdominal crease.44 This positioning is employed by the senior author as well. Although surgeons’ opinions differ, several studies have demonstrated that the most aesthetically appealing umbilicus is vertical- or oval-shaped, with superior hooding, and without protrusion.44,45 However, the formation of the umbilicus remains as controversial in DIEP flap reconstruction as it does in the abdominoplasty literature. The umbilical incision can be round, vertical ellipse, or U- or inverted U-shaped while the abdominal incision can be round, vertical ellipse, U- or inverted U-, or V- or inverted V-shaped.46 Most techniques involve defatting the umbilical stalk. Other modifications include plicating the umbilical stalk and suturing the dermis of the stalk to the abdominal fascia (Video 3).46

Abdominal Closure

Several techniques described in the abdominoplasty literature can be applied to the DIEP donor site during closure to further improve aesthetics. Before closure, plication with nonabsorbable sutures should be considered to create a more contoured torso in patients with significant rectus diastasis. Efforts can then be focused on achieving a tension-free closure to improve scarring on the lower abdomen and prevent scar widening. The senior author utilizes absorbable progressive tension sutures to both sculpt the abdomen as well as relieve tension on the inferior incision, which has been shown to decrease the rate of donor site wound dehiscence.47 Running unidirectional barbed sutures between the abdominal wall and the abdominal flap while advancing under tension along the linea semilunaris can relieve tension on the inferior abdominal closure (Figure 4). This running–barbed suture quilting technique has the added advantage of obliterating dead space and reducing abdominal drainage (Video 3).48 In addition to obliterating dead space, the senior author places 2 drains in the abdominal donor site. An alternative technique adopted from the abdominoplasty literature is the cannula-assisted, limited undermining, and progressive high-tension suture technique, which has demonstrated improved scar quality with a decreased complication profile.49 Finally, the skin edges should be closed with an atraumatic technique and perfect eversion of the dermis.

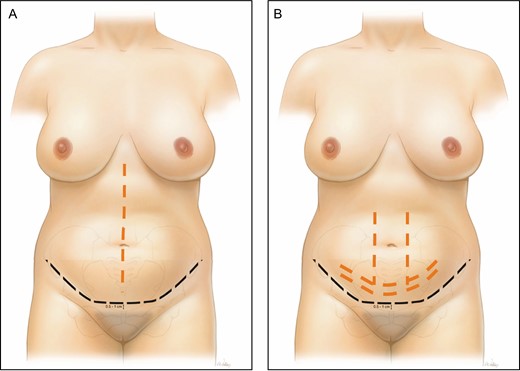

(A) Diagram of the ideal abdominal scar position (black line) for deep inferior epigastric perforator flap donor site closure and the location for the plication sutures (orange line) in patients with significant rectus diastasis. (B) Location of the progression tension sutures between the abdominal wall and the abdominal flap and along the inferior incision (orange line).

Postoperative management of the scar can be just as important as the surgical closure. Topical clobetasol, intralesional triamcinolone injections, and silicone gel sheeting are the mainstays of hypertrophic and keloid scar management.50 Surgical glue or tape can provide additional support and offload tension on the scar. Should depression of the scar develop, fat grafting with rigotomy at the time of revisional surgery is an option.

CONCLUSIONS

This review reflected the senior author’s techniques and perspectives for optimizing aesthetics in autologous breast reconstruction and is therefore a limited overview and not meant to serve as a comprehensive reference on the topic. Further, the review is retrospective in nature. Outcomes were not included in this study but were previously published.9,12,51 Prospective studies may be designed moving forward to investigate outcomes with different techniques for flap inset and shaping or abdominal closure; however, aesthetics outcomes are challenging to quantify.

Innovations in autologous-based breast reconstruction have optimized surgical outcomes and improved the aesthetics of the final reconstruction. With refinements in managing both the abdominal donor site and the breast recipient site, autologous breast reconstructions are able not only to restore form but also to meet patients’ aesthetic goals. The field of breast microsurgery is once again pushing boundaries to improve function with DIEP flap neurotization and vascularized lymph node transfer. As reconstructive surgeons, we hope we can continue to take steps to enhance the quality of life, psychological well-being, body image, and sexual health of patients desiring reconstruction.

Disclosures

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Funding

This supplement is sponsored by Allergan Aesthetics, an Abbvie Company (Irvine, CA), Mentor Worldwide, LLC (Irvine, CA), and 3M+KCI (St. Paul, MN).

REFERENCES

Author notes

Dr Doval is a Research Fellow