-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Mihye Choi, Jordan D Frey, Optimizing Aesthetic Outcomes in Breast Reconstruction After Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy, Aesthetic Surgery Journal, Volume 40, Issue Supplement_2, December 2020, Pages S13–S21, https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjaa139

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Nipple-sparing mastectomy (NSM) has been associated with improved quality of life and patient satisfaction with similar oncologic outcomes compared with traditional mastectomy techniques. By conserving the nipple-areola complex and the majority of the breast skin envelope, NSM allows for improved aesthetic outcomes after breast reconstruction. However, the technique is also associated with a steep learning curve that must be considered to achieve optimal outcomes. It is important that the plastic surgeon functions in concert with the extirpative breast surgeon to optimize outcomes because the reconstruction is ultimately dependent on the quality of the overlying mastectomy flaps. Various other factors influence the complex interplay between aesthetic and reconstructive outcomes in NSM, including preoperative evaluation, specific implant- and autologous-based considerations, as well as techniques to optimize and correct nipple-areola complex position. Management strategies for complications necessary to salvage a successful reconstruction are also reviewed. Lastly, techniques to expand indications for NSM and maximize nipple viability as well as preshape the breast are discussed. Through thoughtful preoperative planning and intraoperative technique, ideal aesthetic results in NSM may be achieved.

Nipple-sparing mastectomy (NSM) is the latest advancement in the surgical treatment of breast cancer, permitting near complete preservation of the breast skin envelope along with the nipple-areola complex (NAC).1-5 NSM has been associated with improved quality of life and patient satisfaction with similar oncologic outcomes compared with traditional mastectomy techniques.5-8 In properly selected patients, NSM affords the plastic surgeon the ability to perform a more natural, anatomic, and aesthetic reconstruction compared with traditional mastectomy techniques.9 NSM with reconstruction has been performed at our institution since February 2006 and continues into the present (May 2020). All evidence presented from our institution in this review was collected during this time frame. All associated studies were approved by the institutional review board at NYU Langone Health.

Indications for NSM continue to expand while multiple patient-, disease-, and operative-specific factors have been examined in an effort to determine overall risk.2,10-16 Various factors have been identified as increasing the risk for complications after NSM, including incision choice, mastectomy indication, chemotherapy, reconstructive modality, and mastectomy weight, among others.2-4,14-17 Meanwhile, various factors, including severe grade II or grade III breast ptosis along with significant macromastia, NAC/chest wall asymmetry, and poor breast skin quality such as significant striae and/or skin laxity, represent relative contraindications for NSM due to an increased risk of aesthetic and reconstructive compromise.

Outside of patient selection, various techniques and maneuvers in breast reconstruction after NSM can be employed to maximize aesthetic outcomes and patient satisfaction. Proper mastectomy flap dissection sets the foundation for a successful reconstruction while optimization of nipple position and appearance is paramount. Nipple position may also be altered in the primary or secondary setting as necessary. Important and unique considerations exist in optimizing aesthetics in implant- and autologous-based reconstruction after NSM, respectively. Additionally, managing complications is an important aspect of ensuring an ultimately viable and natural reconstruction. Finally, staged breast reduction and NSM as well as nipple delay may be employed in certain circumstances to improve nipple position and viability, respectively, thus allowing the surgeon to offer NSM to patients who otherwise may not be candidates.

Oncologic Safety of Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy

It is imperative that the plastic surgeon understands oncologic considerations in patient selection and operative technique. Overall, oncologic outcomes with NSM appear similar to traditional mastectomy techniques, with rates of locoregional recurrence ranging from 0.0% to 25.7%.6-8,18 Current United States National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines suggest that NSM is best reserved for biologically favorable, early-stage cases with no nipple discharge, Paget’s disease, or nipple involvement on imaging.19 Further, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends that invasive breast cancer or ductal carcinoma in situ should be at least 2 cm from the nipple and that the nipple margin is assessed to be clear intraoperatively.13 However, 1 recent publication based on imaging studies recommended that only patients with clinical NAC tumor involvement be excluded from NSM.20

In examining our oncologic outcomes in NSM with follow-up over 4 years, locoregional recurrence after NSM was 2.0%, and tumor-to-nipple distances ≤1 cm trended towards increased risk of recurrence.21 Therefore, in our practice, patients with tumors <1 cm from the nipple margin are not oncologic candidates for NSM. Intraoperatively, we perform frozen subareolar biopsies, which we have identified as highly specific and moderately sensitive.22 Therefore, if a positive frozen result is obtained, the surgeon can confidently remove the NAC because false-positive results are rare. Permanent subareolar biopsies are also sent given the moderate sensitivity of the frozen biopsies; if the permanent result is positive after a false negative frozen biopsy, the NAC is excised in a delayed fashion. In understanding these considerations and working in concert with breast surgeons in NSM, oncologic outcomes are not compromised in the pursuit of superior aesthetic breast reconstruction outcomes.

Preoperative Evaluation

Patients consulting for NSM should undergo a comprehensive assessment to ascertain their candidacy, notably a complete breast examination. Patient history must be assessed, including a determination of past medial and surgical history, body mass index (BMI), and smoking status, among other considerations. Specifically related to smoking status, pack-year and time-to-quitting smoking should be determined because patients undergoing NSM with a <10 pack-year history and >5 years to quitting smoking have demonstrated equivalent outcomes to nonsmokers.15

Bilateral breasts are examined for any obvious or palpable lesions. Any significant findings related to breast pathology should be discussed with and confirmed by the patient’s surgical oncologist, because both parties must agree that the patient is an oncologic candidate for NSM prior to proceeding. Additionally, the need for chemotherapy and radiation will influence outcomes, both aesthetic and otherwise, and should be fully considered and discussed with patients.

Once the patient is established as a candidate for NSM from an oncologic standpoint, reconstructive considerations must be evaluated. The overall chest wall and breast footprint(s) are examined. Severe chest wall or breast asymmetry may not represent absolute contraindications for NSM, though they may lead to significant NAC asymmetry postoperatively. Although mild-to-moderate nipple asymmetry may be remedied intraoperatively or in secondary revisions, severe NAC asymmetry is difficult to correct and is a relative contraindication to NSM.23 Any asymmetries should be discussed with the patient preoperatively. The breast is also examined for prior surgical scars, especially Wise pattern scars from a prior breast reduction or mastopexy or prior lumpectomy incisions, which may be incorporated into the NSM incision or ignored if limited or from the distant past. Periareolar scars should be carefully examined because more recent incisions may compromise blood supply and NAC outcomes and more distant scars may serve as a delay to the NAC to improve perfusion.

A history of breast augmentation should also be ascertained along with the implant information and plane of implant placement, if known. Augmentation will result in a decrease in the amount of breast tissue. In these cases, if implant-based reconstruction is selected by the patient and surgeon, the prior implant pocket can be utilized for tissue expander or permanent implant placement so long as care is taken during the mastectomy to preserve the implant capsule. A history of prior aesthetic breast surgery should not affect the aesthetic outcomes of NSM beyond the pre-NSM aesthetic appearance of the breast (ie, presence of scars from prior aesthetic breast surgery).

Breast size and ptosis are evaluated. Patients with small- to moderate-sized breasts and grade I to mild grade II ptosis (sternal notch to nipple distance ≤27 cm) represent ideal candidates for NSM. Macromastic patients or those with severe grade II to grade III ptosis (sternal notch to nipple distance >27 cm) should be approached cautiously. In these patients, there is a greater distance from the peripheral breast skin perforators to the wound edges and NAC, increasing risk of poor perfusion, ischemic complications, and poor aesthetics. Further, the NAC is often not optimally positioned on the most projecting portion of the breast in these patients, increasing the risk of postoperative nipple malposition.23 Lastly, the larger breast envelope, which is preserved in NSM in these patients, is often mismatched to the underlying implant- or autologous-based reconstruction, risking poor aesthetic outcome. Therefore, patients with larger or more ptotic breasts are best served with skin-sparing techniques or by undergoing delayed NSM after staged reduction mammaplasty to reduce breast parenchyma and skin as well as optimize nipple position. Immediate breast reconstruction in NSM employing a skin reduction pattern incision is also possible but discouraged because it is prone to high rates of wound-healing complications, which can compromise reconstructive and aesthetic success.

The quality and laxity of the breast envelope is assessed. Good breast skin quality and minimal laxity, represented by a pinch test >2 cm and snap-back in each breast quadrant, are optimal. In these patients, the breast skin envelope can accommodate well to the underlying reconstruction. Further, any intraoperative techniques to optimize preexisting nipple asymmetry will be well tolerated, maximizing the likelihood of a superior aesthetic result.

Next, options for reconstruction should be discussed. Desired postoperative breast size is an important consideration, because desire for larger breast sizes will inherently require tissue expansion. Ideal candidates for immediate, 1-stage implant reconstruction are those who desire a similar to slightly larger or more full postoperative breast size. Consideration of these desires can improve postoperative patient satisfaction with aesthetic outcomes.24 Patients desiring autologous reconstruction should undergo examination of potential donor sites to assess for availability.

Lastly, patients must be counseled on the possibility of adjustments to the operative plan based on intraoperative findings. Factors requiring such adjustments may include positive findings of subareolar biopsy or poor perfusion on assessment of the mastectomy flaps intraoperatively. In cases of planned 1-stage implant-based reconstruction, patients must also be aware of the possibility of changing to placement of a tissue expander to minimize tension on the overlying mastectomy flaps and NAC or delaying breast reconstruction. If the intraoperative nipple biopsy is positive for cancer or the nipple is found to be ischemic and requires excision during the initial case, a plan on how to handle the contralateral nipple needs to be discussed. The indications for secondary revisions are also discussed, including the potential need for NAC repositioning due to malposition.25

Our institution has developed an algorithm to assist in predicting individual patients’ risks for complications in NSM.26 This algorithm may be utilized by surgeons and patients alike to assist in the shared decision-making process regarding the type of mastectomy and breast reconstruction to perform. Although this risk calculator does not directly inform aesthetic outcomes, the interplay between reconstructive and aesthetic outcomes cannot be overstated, making this a powerful tool for plastic surgeons consulting with patients desiring NSM. This algorithm and risk calculator is available online (www.nsmriskcalc.com).

Importance of Mastectomy Flap Quality

Mastectomy flap quality and perfusion are paramount to the success of any breast reconstruction. However, this is even more notable in NSM because the majority, if not all, of the breast envelope is maintained along with the NAC. After NSM, the burden of perfusion from the subdermal plexus and subcutaneous perforators is thus greater than traditional mastectomy techniques. Although discussed in greater depth elsewhere, it is imperative that the mastectomy be performed in the anatomic plane of the breast capsule. In doing so, the oncologic resection will be maximized while trauma to the skin envelope will be minimized, resulting in optimally perfused skin flaps to support the underlying reconstruction.27

We have importantly identified that ideal mastectomy flaps are not one-size-fits-all because flap thickness depends on patient anatomy and location within the breast. The thickness of the ideal breast skin flap increases as one progresses from anterior to posterior in the breast. Further, patients with larger breasts and higher BMI tend to have thicker mastectomy flaps, on average, compared with patients with small breasts and/or low BMI.28 This again emphasizes the importance of an anatomic mastectomy dissection based on the individual patient’s anatomy rather than achieving any one particular value for overall mastectomy flap thickness.

Maximizing mastectomy flap quality will set the groundwork for a successful aesthetic outcome after breast reconstruction in NSM because any areas of poor perfusion will compromise the reconstruction secondary to ischemic insult, even if only partial thickness.26

Considerations in Implant-Based Reconstruction

Implant-based breast reconstruction remains the most commonly performed method of breast reconstruction. Indications for single-stage reconstruction with an immediate implant or 2-stage reconstruction with a tissue expander are similar as for non-NSM cases. Combining immediate implant reconstruction with NSM allows for a “breast in a day” reconstruction without the implicit need for a secondary operation.3 Importantly, mastectomy flap quality should be carefully assessed prior to proceeding with reconstruction. This may be conducted clinically or utilizing adjunctive modalities, such as fluorescent angiography. Any clearly nonviable tissue should be carefully assessed, including the NAC. Mild decreases in overlying skin flap perfusion lead us to utilize nitropaste and/or hyperbaric oxygen therapy postoperatively. Moderate to severe decreases in perfusion may lead to conversion from immediate implant to tissue expander–based reconstruction, decrease in intraoperative tissue expander fill, or delaying the reconstruction. If the decreased perfusion is limited to a small area, excision is a possibility. Not doing so will compromise both reconstructive and aesthetic outcomes as well as risk reconstructive failure with device exposure.

Prepectoral as well as total and partial submuscular techniques are utilized in NSM for implant-based reconstruction. Prepectoral alloplastic breast reconstruction has seen a resurgence of popularity. The main indications in prepectoral reconstruction are healthy and viable mastectomy flaps as well as a tumor that is not locally advanced or close to the pectoralis muscle. Prepectoral tissue expander or immediate implant placement allows for the device to interact with the tissue envelope directly without any intervening muscle, although scaffold coverage is usually employed. This is advantageous because construction of the breast contour, specifically medial fullness, and positioning of the NAC over the device can be more straightforward while animation deformity is obviated. However, healthy mastectomy flaps are imperative because any ischemic damage will result in prosthesis exposure and risk reconstructive failure. Upper pole fullness is also often lacking, and rippling can be an issue given the absence of the overlying pectoralis muscle, which can necessitate primary or secondary fat grafting (Supplemental Figure 1).

In total or partial submuscular approaches, the pectoralis muscle is elevated to the level of the superior breast border and medially to the sternal attachments to provide medial cleavage. It is imperative in NSM that the underlying implant pocket be matched to the overlying skin envelope, which is completely or largely preserved compared with non-NSM techniques. Not doing so will result in NAC malposition and an unaesthetic breast shape. Patients with very small breasts may be served with total submuscular coverage. However, scaffold support to expand and cover the inferolateral aspect of the implant pocket is employed in the majority of cases. The scaffold of choice in our practice is contour, fenestrated human acellular dermal matrix. In cases of scaffold utilization, the inferior pectoralis is released from its origins to the level of the medial attachments. The scaffold is secured to the inframammary fold inferiorly and the chest wall at the level of the anterior axillary line laterally to define the breast footprint. The device, whether a tissue expander or permanent implant, may then be placed, and the scaffold is sutured to the edge of the pectoralis, providing complete coverage. In total submuscular coverage, the serratus fascia and/or muscle are elevated to the level of the anterior axillary line, after which the device is placed and the muscle/fascial edges are sutured (Supplemental Figures 2 and 3).25

Considerations in Autologous Reconstruction

Autologous reconstruction after NSM proceeds similarly to non-NSM procedures; however, particular care in incision choice is necessary to optimize exposure for recipient vessel dissection. In these cases, care must be taken to minimize prolonged retraction on the skin flaps, which is often required for recipient vessel exposure and microsurgery. Prolonged retraction can lead to increased skin tension and pressure, further leading to ischemic complications of the NAC and mastectomy flaps. Multiple periods of relaxation of the skin flaps from retraction and gentle retraction when necessary are recommended to minimize this stress. The choice of NSM incision can also assist in minimizing the impact of retraction in microsurgical NSM reconstruction. Vertical radial and Wise pattern incisions offer superior access to the internal mammary vessels compared with inframammary fold incisions in these cases, especially in patients with larger breasts (Figure 1).16

This 49-year old female patient with recurrent left breast cancer after lumpectomy and radiation underwent bilateral nipple-sparing mastectomy with autologous lateral thigh perforator flap reconstructions. Patient is shown (A) preoperatively, (B) 3 months postoperatively after immediate lateral thigh perforator flap reconstruction through vertical mastectomy incisions, and (C) 1 year after initial reconstruction now after skin paddle excision and 1 session of autologous fat transfer to bilateral breasts.

Ensuring an aesthetic breast shape and projection in autologous reconstruction after NSM is paramount. The breast dimensions and footprint should be noted and compared with the flap dimensions prior to flap insetting. Our preference is to inset the midline portion of the flap along the inframammary fold, setting the base width of the new breast footprint. The tapered edge of the flap thus can be inset superiorly, extending slightly into the axillary tail to fill this area, which otherwise will be hollow. Care is also taken to ensure that the flap fills the hollow over the dissected internal mammary vessels, especially if a rib-sacrificing approach is utilized. In patients with preoperative wider breast base widths, the superior edge of the flap can be inset along the inframammary fold, recreating a footprint with a longer base width if desired.

Similar to 1-stage implant reconstruction, autologous reconstruction after NSM can, in theory, be performed in a single stage without the implicit need for a secondary operation. This can be achieved by placing the autologous tissue in a buried fashion under the mastectomy flaps without a skin paddle. However, we prefer to leave a small skin paddle for monitoring within the utilized mastectomy incision in these cases with the paddle being simply excised secondarily. In this manner, flap monitoring is more reliable and not dependent on internal monitoring devices with high false-positive readings or on nonspecific clinical signs such as turgor and warmth, which may be confounded by the overlying skin flaps. Additionally, we found that those with buried and nonburied flaps after NSM had similar rates of revisionary procedures.29

Notably, autologous reconstruction may also be utilized as a salvage modality after failed implant-based reconstruction.30 These cases are complicated by a scarred and often contracted breast pocket with malpositioned nipples. Care must be taken to release the breast pocket as much as possible as well as optimize nipple position. If native breast skin is missing as a result of complications from the index prosthetic reconstruction, flap skin should be used as needed to allow the breast envelope to expand. The autologous flap may then be shaped appropriately to reconstruct the breast footprint.

Optimizing Nipple Position and Appearance

Establishing symmetric and anatomic NAC positioning is a primary goal in NSM that can often be one of the most difficult to achieve. However, this goal is essential in attaining an aesthetic result after NSM.23 In 1 survey, NAC position was rated as the second most common NAC-related aspect that patients wished they could change after NSM.31 Various techniques are available to address NAC positioning in a primary manner as well as correct malposition in a secondary fashion.

Perhaps most important in addressing aesthetic nipple positioning in NSM is the preoperative patient evaluation. The preoperative position of the NAC on the breast should be discussed as well as any chest wall deformities present. The impact of these findings on postoperative results should be discussed as well as the potential need for repositioning. Ideally, the NAC is placed on the most projecting part of the breast postoperatively. Some patients may have differing ideals related to NAC position, however. This needs to be discussed and plans for NAC position can be altered accordingly.23

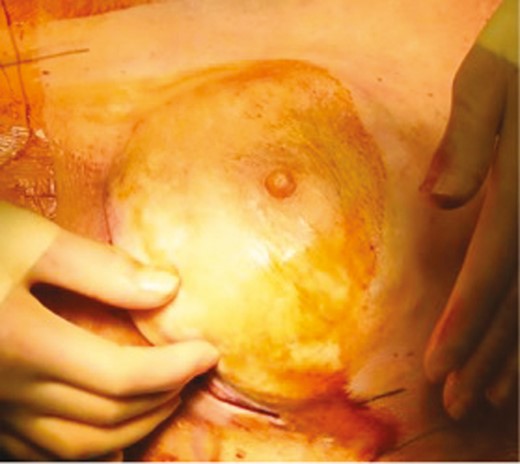

Various techniques exist for primary and secondary manipulation of NAC position in NSM. Careful attention must be paid to optimizing NAC position at the time of initial NSM and reconstruction. Our practice for setting NAC position is to either secure the NAC to the underlying muscle or acellular dermal matrix or to set the position after incisions are closed and immediately place drains to closed suction.23 Again, the NAC is positioned at the most projecting part of the breast or in accordance with patient preference (Figure 2).

Intraoperative photograph (patient age unknown) demonstrating redraping of the mastectomy flap over the implant in a case of immediate implant reconstruction and nipple-sparing mastectomy. Note that the nipple-areola complex is optimally placed over the most projecting part of the reconstruction. The underside of the nipple may then be secured to the underlying muscle or scaffold to hold this position. This will maximize aesthetic results and minimize risk of postoperative nipple malposition.

In our study of more than 1000 cases of NSM, 77 (7.4%) underwent NAC repositioning in a delayed fashion. Cases requiring NAC repositioning were significantly more likely to have preoperative radiation, a vertical or Wise pattern incision, autologous reconstruction, and minor mastectomy flap necrosis. Previous radiation (odds ratio [OR] = 3.6827), vertical radial mastectomy incisions (OR = 1.8218), and autologous reconstruction (OR = 1.77) were positive independent predictors of NAC repositioning, whereas implant-based reconstruction (OR = 0.5552) was a negative independent predictor of repositioning. The most common techniques were crescentic periareolar excision (32.5%), capsule modification (18.2%), and directional skin excision (13.0%). In cases of malposition in implant-based reconstruction, the source of malposition is identified as due to either a skin issue or a capsule issue.

Crescentic periareolar and directional skin excisions are performed in cases in which the NAC requires mild to moderate repositioning due to skin issues. Crescentic periareolar excisions are performed as a crescent adjacent to the NAC, whereas directional skin excision is performed as a skin excision remote to the periareolar to reposition the NAC along a vector. Mastopexy-type procedures may be utilized for more severe NAC malposition due to a skin issue when greater repositioning is required. Capsule modification, including capsulotomy, capsulectomy, and capsulorrhaphy, is utilized in cases of malposition due to a capsule issue, such as capsular contracture.23,25

Notably, in alloplastic NSM reconstruction, NAC repositioning must take place with care to avoid injuring the underlying implant. Further, the NAC is nourished only via the subdermal plexus of the prior mastectomy flaps, increasing the risk of ischemic NAC compromise and precluding the ability to redevelop mastectomy flap planes in mastopexy-like NAC-altering procedures. In cases addressing skin-related issues, the dermis is not incised, but intervening tissue is rather deepithelialized during any mastopexy-type procedure to preserve NAC vascularization. Conversely, in autologous NSM reconstruction, the NAC derives its blood supply via the mastectomy flap subdermal plexus but also secondarily from the underlying vascularized flap tissue. More aggressive NAC repositioning maneuvers, such as Wise pattern mastopexy techniques, can thus be employed.23,25

Lastly, preliminary breast reshaping via staged breast mastopexy or reduction prior to NSM is a very useful and effective method of optimizing NAC position in NSM as will be discussed below.

Nipple appearance after NSM is also a critical factor in the aesthetic success of the procedure. In terms of projection, certain patients may desire reduction or augmentation of the nipple after NSM. Nipple reduction may be performed with a simple wedge excision. For nipple height reduction, nipple skin can be excised as a ring or cylinder below the top of the nipple. Nipple augmentation may be accomplished utilizing fat or dermal grafts as well as fillers. Augmentation can be particularly useful as the utilization of subareolar biopsies for oncologic safety can often result in under-projection of the nipple. This may also be useful in the setting of partial-thickness nipple necrosis in which nipple projection may still be lacking after wound healing is complete. In cases of complete, full-thickness nipple necrosis, secondary nipple reconstruction can be undertaken after the resultant wound is fully healed via local flap techniques, including C-V and skate flaps.25 Utilizing areolar tissue is very effective because a “like with like” reconstruction is provided. Lastly, a tattoo technique may also be employed in cases of ischemic insult to the NAC after healing is complete to refine or recreate the NAC aesthetic unit with satisfactory success.

Managing Complications

In appropriately selected patients, the overall risk of complications in NSM is low, generally ranging from 1% to 13%.4,25 However, appropriate management of these complications, especially ischemic complications, can salvage an aesthetic outcome for the patient. As discussed above, we have developed a risk assessment algorithm and calculator that can help to predict the risk of overall reconstructive complications after NSM.25 Discussion regarding reconstructive risks and their impact on aesthetic outcomes must be undertaken with patients preoperatively. If risk is deemed to be too high or if patients are not willing to accept the potential impact of those risks on outcome, non-NSM techniques should be pursued.

Ischemic complications after NSM should be prudently monitored for and diagnosed in the outpatient setting. Partial-thickness or minor NAC and mastectomy flap necrosis, with an incidence ranging from 5% to 13%, can be managed conservatively employing local wound care.4,25 However, full-thickness NAC and mastectomy flap necrosis, ranging from 1% to 7%, should be managed aggressively with excision and closure, especially in alloplastic reconstructions to minimize risk of reconstructive failure.4 In many cases, this is possible in the office setting under local anesthesia with primary reclosure. However, when larger areas of mastectomy skin are affected, debridement and excision is best performed in the operating room because device deflation, replacement, or removal may be necessary.25

Autologous reconstruction permits greater flexibility in the management of full-thickness NAC or mastectomy flap necrosis in NSM because there is no foreign device that risks infection with exposure. Primary closure should be attempted after excision of necrotic tissue. However, larger wounds may be managed with local wound care or skin grafting with plans for secondary excision. When there is concern for mastectomy flap ischemia intraoperatively, flap skin may be “banked” under the mastectomy flaps. This banked skin can then be utilized if full-thickness mastectomy flap ischemia occurs or excised if not in a secondary fashion.

Strategies to Improve Nipple Viability and Expand Indications in Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy

Staged Breast Reduction Prior to Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy

Staged breast reduction and NSM can be performed in patients with significant breast ptosis (sternal notch to nipple distance >27 cm), larger breast size—which can increase complication in NSM17—or preoperative nipple malposition. Staged reduction can decrease complications compared with matched patients undergoing NSM without staged reduction.31 Through pre-NSM breast reduction or mastopexy, the nipple position can be optimized and the glandular tissue reduced, allowing greater control of the aesthetic outcome prior to definitive NSM and reconstruction. Additionally, the skin flaps and NAC are effectively delayed, increasing vascularity and minimizing risk of ischemic complications and their sequela. In our experience, this is offered for risk reduction to patients undergoing mastectomy who are otherwise good candidates for NSM with breast ptosis, large breast size, or malposition. In general, the waiting period between reduction and NSM is 3 months. Other groups have similarly performed staged reduction and NSM in cases of therapeutic mastectomy with shorter waiting periods. However, we believe that 3 months is an optimally safe period to reduce the risk of wound-healing complications, obviating the technique from therapeutic cases in which the mastectomy should not be additionally delayed.32 As such, we currently only offer this technique to those undergoing NSM for risk reduction due to family history or genetic predisposition.

In cases in which 3 months cannot be safely waited between breast reduction and NSM, such as in patients undergoing therapeutic mastectomies, a lumpectomy with a oncoplastic breast reduction and contralateral symmetrizing breast reduction may be performed at the index procedure. After a safe period has elapsed, 3 months in our experience, the patient may then undergo bilateral NSM and the reconstruction of their choice. The advantage of this approach in therapeutic cases is that chemotherapy may be allowed to proceed before NSM and reconstruction, preventing any potential delays. Further, and perhaps even more important, radiotherapy can often be avoided.

Nipple Delay

Nipple delay is a procedure in which the NAC is variably undermined through a remote incision before a definitive NSM is performed. In this manner, the vascularity of the NAC can be improved in a staged fashion. Issues regarding the waiting period between the delay procedure and the definitive extirpation again persist. Although useful in prophylactic cases, some centers advocate for performing the nipple delay along with lumpectomy in an initial stage so long as the tumor is not subareolar, followed by definitive NSM and breast reconstruction in a second stage. The deleterious impact of waiting for cancer excision between stages is thus mitigated. Subareolar biopsies may also be taken at the time of delay. Nipple delay is another management strategy for patients at increased risk of ischemic complications, although staged reduction as described above is our preferred technique in those with large breasts or significant ptosis.33

CONCLUSIONS

NSM has unlocked the potential to offer patients improved aesthetics, quality of life, and satisfaction after mastectomy and breast reconstruction. It is imperative for the plastic surgeon to appreciate the intimate interplay between aesthetic and reconstructive outcomes in NSM. In this regard, an understanding of oncologic considerations as well as overall risk profile for complications is of utmost importance. Collaboration with the breast surgeon will facilitate a maximization of the quality of mastectomy flaps through an anatomic dissection. Aesthetic results will further be optimized through careful preoperative evaluation as well as meticulous technical consideration and execution. Factors such as breast shape and chest contour, mastectomy flap creation, nipple position and appearance, and implant- and autologous-related factors among others must be acutely accounted for in NSM. In this manner, unparalleled outcomes can be achieved and offered to patients undergoing NSM and breast reconstruction for breast cancer or risk reduction.

Disclosures

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Funding

This supplement is sponsored by Allergan Aesthetics, an Abbvie Company (Irvine, CA), Mentor Worldwide, LLC (Irvine, CA), and 3M+KCI (St. Paul, MN).

REFERENCES