-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Mahsa Jessri, Deirdre Hennessey, Ana Bader Eddeen, Carol Bennett, Claudia Sanmartin, Douglas Manuel, Mortality and Life Expectancy Lost in Canada Attributable to Dietary Patterns: Evidence From Canadian National Nutrition Survey Linked to Routinely Collected Health Administrative Databases, American Journal of Epidemiology, Volume 192, Issue 3, March 2023, Pages 377–396, https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwac189

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

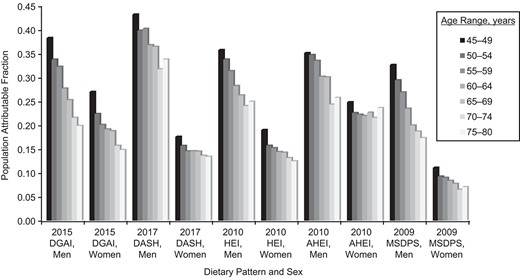

Using 5 diet quality indexes, we estimated the mortality and life expectancy lost, at the national level, attributable to poor dietary patterns, which had previously been largely unknown. We used the Canadian Community Health Survey 2004, linked to vital statistics (n = 16,212 adults; representing n = 22,898,880). After a median follow-up of 7.5 years, 1,722 deaths were recorded. Population attributable fractions were calculated to estimate the mortality burden of poor dietary patterns (Dietary Guidelines for Americans Adherence Index 2015, Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension, Healthy Eating Index, Alternative Healthy Eating Index, and Mediterranean Style Dietary Pattern Score). Better diet quality was associated with a 32%–51% and 21%–43% reduction in all-cause mortality among adults aged 45–80 years and ≥20 years, respectively. Projected life expectancy at 45 years was longer for Canadians adhering to a healthy dietary pattern (average of 5.2–8.0 years (men) and 1.6–4.1 (women)). At the population level, 26.5%–38.9% (men) and 8.9%–22.9% (women) of deaths were attributable to poor dietary patterns. Survival benefit was greater for individuals with higher scores on all diet indexes, even with relatively small intake differences. The large attributable burden was likely from assessing overall dietary patterns instead of a limited range of foods and nutrients.

Abbreviations

- AHEI

Alternative Healthy Eating Index

- CCHS

Canadian Community Health Survey

- CI

confidence interval

- DASH

Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension

- DGAI

Dietary Guidelines for Americans Adherence Index

- DPMP

Dietary Patterns Methods Project

- HEI

Healthy Eating Index

- HR

hazard ratio

- MSDPS

Mediterranean Style Dietary Pattern Score

With the dramatic increase in life expectancy during the 20th century, we can be more optimistic that good health is achievable and sustainable. Unlike smoking, whose contribution to death and disease has been steadily decreasing, the contribution of poor diet has been increasing—poor diet is now one of the most common preventable behavioral risks for chronic diseases in Canada (1). Despite the leading role of poor dietary patterns in health, there is a lack of evidence regarding the overall mortality burden (attribution) of unhealthy dietary patterns in large, prospective, nationally representative surveys worldwide. The most cited estimates, provided by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation Global Burden of Disease studies, are based on a few selected foods and nutrients (2, 3) that are not available for all countries. This single-nutrient approach is limited in its ability to consider the multidimensionality of dietary intake exposure, and to detect small effects of single dietary constituents (4).

Conceptually, examining overall dietary patterns is more in line with the real world, where individuals do not consume single isolated nutrients but rather varied meals with complex combination of foods and nutrients (5). The dietary pattern approach is promising for examination of chronic diseases, since when one component of diet changes, it is substituted by another and therefore it is the “synergistic and antagonistic” effects of nutritional components that predict the chronic disease risk (6). Examining dietary patterns is increasingly recognized as an approach for informing public health recommendations. However, the most recent systematic reviews of dietary patterns—performed by the US Department of Agriculture—demonstrated an underdeveloped evidence base for longitudinal association of dietary patterns with several health outcomes (5, 7, 8). Particularly, the National Cancer Institute’s Dietary Pattern Methods Project (DPMP) and the US Department of Agriculture (8–10) have identified the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) (11), Healthy Eating Index (HEI) (12), Alternative Healthy Eating Index (AHEI) (13), Mediterranean Style Dietary Pattern Score (MSDPS) (14), and Dietary Guidelines for Americans Adherence Index (DGAI) (15) as dietary patterns commonly used in North American populations with relevance to dietary guidelines (10).

The lack of nationally representative burden estimates for dietary patterns is a critical gap in policy development. Previous evaluation of successful public health policy has indicated that burden estimates are critical as they provide powerful input for policy and can constitute a “business case” for public health policy development (16, 17). This is important as modification of dietary intake is a cornerstone for prevention policy (18). As such, population burden measures that estimate the number of preventable events achievable through the reduced prevalence of modifiable risk factors are of high relevance for resource allocation, primary prevention, and prioritization (19).

The evidence supporting the protective effects of healthy dietary patterns has been derived mainly from prospective cohort studies among middle-aged or older adults, with known limitations (e.g., potential selection bias and lack of generalizability, use of a single food frequency questionnaire, ignoring measurement errors) (10, 20). To our knowledge, no previous study has examined the population burden of mortality attributable to poor dietary patterns at the national level. The concept of a dose-response relationship between dietary patterns and mortality is still controversial, and the type of dietary pattern most beneficial for primary prevention needs further clarification, especially in diverse countries following Western-type dietary patterns (21).

Given the limited evidence on the topic, we addressed the following a priori research questions: 1) Are healthier dietary patterns, as characterized by higher scores on 5 common diet quality indexes, consistently associated with reduced risk of all-cause mortality? 2) Are different index scores equally protective, and is there a rank (e.g., percentile) at which mortality benefit begins (i.e., prognostic utility of indexes)? And 3) what is the population attributable fraction of mortality and estimated life expectancy lost due to poor dietary patterns? In addressing these research questions, attention was given to mitigating the effect of random and systematic measurement errors in self-reported dietary recalls.

METHODS

This study was approved by the Ottawa Health Science Network Research Ethics Board. Data were collected under the authority of the Statistics Act of Canada and were accessed and analyzed at Statistics Canada (Ottawa, Canada). Data linkages were completed through funding from Statistics Canada, Health Canada, and Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Study population and design

We used data from the first Canadian national nutrition survey—the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS), Nutrition, 2004—linked to the Canadian Vital Statistics Death Database. The CCHS-Nutrition 2004 is a cross-sectional, multistage and complex survey conducted by Statistics Canada (January 2004 to January 2005), representing approximately 98% of the Canadian population (response rate = 76.5%) (22, 23). Trained interviewers used the modified US Department of Agriculture automated multiple-pass method to collect standardized 24-hour dietary recalls (24). A second 24-hour dietary recall was collected by phone from approximately 30% of participants, 7–10 days after collecting the first dietary recall. The second day of dietary recalls was used to estimate usual intake distribution by accounting for day-to-day variation in intakes using the National Cancer Institute’s method (25, 26) (Web Appendix 1, available at https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwac189). This variation in the diets of the 30% of the participants with a second recall was used to extrapolate the variability in the diets of those with only 1 day of recall. Participants with either 1 or 2 days of recalls were included in the analysis.

Of 33,469 CCHS-Nutrition 2004 participants who agreed to share their data, 29,897 were linked to the Canadian Vital Statistics Death Database—a census of all deaths registered in Canada (linkage rate = 5.3%). Details on the external and internal validity of the linkage have been previously published (27, 28). Participants in CCHS-Nutrition 2004 were followed to December 31, 2011; participants with no recorded death by this date were censored.

After removing those under 20 years of age, participants with invalid dietary recalls (as defined by Statistics Canada as incomplete, implausible, or lacking sufficient data (n = 35)), and all pregnant and breastfeeding women (n = 191), the sample included 16,212 respondents. Of these, 4,901 (representing 6,147,470 Canadians) had completed the second day of dietary recall. In line with previous studies on the topic (9, 10), we restricted our sample to participants aged 45–80 years in sensitivity analyses, leaving a final analytical sample of 9,174 participants (representing 11,313,844 Canadians) of whom 2,671 (representing 2,953,337 Canadians) had a second day of dietary recalls.

Dietary pattern ascertainment

We defined dietary patterns using several well-established dietary quality indexes that provide a common and standardized metric for comparing findings across populations, including those recommended by the National Cancer Institute’s DPMP (9, 10). All diet quality indexes suggested by the DPMP (10) and the US Department of Agriculture (7)—DASH 2017 (11), HEI 2010 (12), AHEI 2010 (13), MSDPS 2009 (14), and the latest DGAI 2015 (15, 29)—were used. Web Table 1 presents an overview of components and scoring criteria for each of the 5 indexes, and Web Table 2 shows the Pearson correlation coefficients for the association among the indexes.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were weighted using Statistics Canada’s sampling survey weights to ensure a nationally representative sample (23). Analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina), and R, version 3.4.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Missing values for sociodemographic and lifestyle variables were imputed using multiple imputation (Hmisc package) (30) in R with the full list of predictor variables, censoring and time-to-event variables, and auxiliary variables that were not predictors but were helpful for the multiple imputation process. Prior to imputation, a correction factor to correct for the bias in self-reported height and weight (compared with measured anthropometry) was used for body mass index (31). Random and systematic measurement errors (e.g., misreporting) were thoroughly identified and addressed, including by using 2 days of dietary recalls and including misreporting as a covariate (Web Appendix 1) (25, 32–34). A priori sensitivity analyses were conducted (Web Appendix 2).

The Cox model proportional hazards assumptions were verified by plotting weighted Schoenfeld residuals against time-to-event variables, which revealed no evidence of departure from proportionality of hazards over time (35). Terms for interaction of person-time and dietary pattern scores were also nonsignificant, further confirming that assumptions were satisfied. Weighted Cox proportional hazard models with person-days as the time metric were fitted as part of the regression calibration to model time to death—while simultaneously adjusting for influential covariates—to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association of dietary pattern scores and mortality. To maximize the generalizability of findings, most of the covariates used were from a standardized list of covariates determined a priori by the Dietary Patterns Methods Project (age, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, physical activity, smoking, energy intake, body mass index, diabetes, and alcohol intake). All recommended covariates were used in the regression calibration models except for postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy (for models analyzing women), which is not available in CCHS-Nutrition, and race/ethnicity, which was replaced with immigrant status because of power and degrees-of-freedom issues with using race/ethnicity in a mostly Caucasian (as identified in Statistics Canada data) sample (10). Chronic diseases (i.e., heart disease, diabetes, cancer) were included as covariates because of their important contribution to mortality in Canada. As a sensitivity analysis, we also looked at chronic diseases as effect modifiers by adding them as terms for interaction of diet with each of the 3 diseases at baseline in the same model. Additionally, to account for concerns with dietary data collection, models further adjusted for the sequence of dietary recall (first or second) and the day of the week on which the 24-hour recall was collected (weekend/weekday). Weighted and adjusted Kaplan-Meier curves were plotted to represent the probability of survival among groups with different dietary pattern scores, and log-rank statistics were used to measure the equality of ranks. Weighted population attributable fraction was calculated as described in Web Appendix 3.

Baseline Characteristics and Crude Mortality Rates per 10,000 Person-Years (Unweighted) Among Men (n = 7,355), Canadian Adults in Canadian Community Health Survey–Nutrition Linked to Canadian Vital Statistics Death Database, 2004/2005 to 2011

| Variable . | Frequency, % . | Person-Years . | No. of Deaths . | Crude Mortality Rate, Per 10,000 Person-Years . | Age-Standardized Rate . | 95% CI . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline age categories, years | 100 | 52,227.3 | 806 | 154.3 | 126.3 | 117.2, 136.0 |

| <45 | 39.4 | 21,609.1 | 25 | 11.6 | ||

| 45–80 | 55.3 | 28,605.6 | 550 | 192.3 | ||

| ≥80 | 5.3 | 2,012.7 | 231 | 1,147.7 | ||

| Age categories, 10-year intervals | ||||||

| <30 | 18.1 | 9,888.6 | 7 | 7.1 | ||

| 30–39 | 13.1 | 7,198.7 | 8 | 11.1 | ||

| 40–49 | 17.5 | 9,572.2 | 30 | 31.3 | ||

| 50–59 | 18.5 | 10,023.5 | 60 | 59.9 | ||

| 60–69 | 13.0 | 6,679.2 | 140 | 209.6 | ||

| 70–79 | 13.5 | 6,372.9 | 298 | 467.6 | ||

| 80–89 | 5.9 | 2,363.8 | 238 | 1,006.8 | ||

| ≥90 | 0.5 | 128.5 | 25 | 1,945.4 | ||

| Dietary reference intake age groups, years | ||||||

| 19–30 | 19.5 | 10,667.2 | 8 | 7.5 | ||

| 31–50 | 31.2 | 17,116.5 | 40 | 23.4 | ||

| 51–70 | 30.7 | 16,194.5 | 213 | 131.5 | ||

| ≥71 | 18.6 | 8,249.2 | 545 | 660.7 | ||

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Daily/occasional smoker with with ≥20 but <90 cigarettes/day | 11.8 | 6,153.3 | 98 | 159.3 | 240.3 | 187.1, 303.9 |

| Daily/occasional smoker with <20 cigarettes/day | 16.7 | 8,834.1 | 86 | 97.4 | 223.7 | 164.2, 297.6 |

| Former daily/occasional smoker and those who smoked a total of ≥100 cigarettes in lifetime | 36.9 | 18,733.4 | 454 | 242.4 | 121.1 | 108.3, 134.9 |

| Never smoked | 34.6 | 18,506.5 | 168 | 90.8 | 94.3 | 80.0, 110.4 |

| Alcohol consumption over the prior 12 months | ||||||

| None | 16.9 | 8,341.7 | 261 | 312.9 | 159.8 | 139.2, 182.6 |

| Less than 1–3 times per month | 31.8 | 16,697.4 | 248 | 148.5 | 132.2 | 114.6, 151.7 |

| 1–3 times per week | 29.3 | 15,726.5 | 127 | 80.8 | 100.0 | 76.8, 127.9 |

| 4–7 times a week or being binge drinker: drank >2 times per week with the frequency of ≥5 drinks being 1 or more times per week | 22.0 | 11,461.7 | 170 | 1,483.0 | 122.8 | 100.3, 148.9 |

| Physical activity, metabolic equivalents/day | ||||||

| ≥3.0 | 19.7 | 10,491.7 | 97 | 92.5 | 837.0 | 65.5, 105.4 |

| 1.5–3.0 | 24.5 | 13,055.9 | 137 | 104.9 | 965.0 | 75.5, 121.5 |

| <1.5 | 55.8 | 28,679.8 | 572 | 199.4 | 148.8 | 136.3, 162.0 |

| Body mass indexa | ||||||

| <18.5 | 1.1 | 449.2 | 27 | 601.1 | 391.2 | 248.3, 586.4 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 29.4 | 15,139.5 | 285 | 188.3 | 142.3 | 125.6, 160.7 |

| 25.0–29.9 | 40.4 | 21,159.8 | 315 | 148.9 | 117.1 | 102.6, 133.0 |

| ≥30.0 | 29.1 | 15,478.8 | 179 | 115.6 | 129.1 | 105.1, 157.1 |

| Respondent’s highest level of education | ||||||

| Less than secondary school graduation | 26.4 | 13,122.8 | 398 | 303.3 | 148.6 | 131.9, 166.7 |

| Secondary school graduation | 16.6 | 8,833.2 | 80 | 90.6 | 117.2 | 83.0, 160.8 |

| Some postsecondary education | 8.8 | 4,642.2 | 53 | 114.2 | 133.3 | 98.9, 175.8 |

| Postsecondary graduation | 48.2 | 25,629.1 | 275 | 107.3 | 115.9 | 101.4, 132.0 |

| Current diabetes | ||||||

| Yes | 8.4 | 4,057.0 | 151 | 372.2 | 156.5 | 127.6, 190.0 |

| No | 91.6 | 48,170.3 | 655 | 136.0 | 120.7 | 111.1, 130.9 |

| Current heart disease | ||||||

| Yes | 10.3 | 4,712.0 | 250 | 530.6 | 161.6 | 138.5, 187.5 |

| No | 89.7 | 47,515.3 | 556 | 117.0 | 118.0 | 107.6, 129.3 |

| Current cancer | ||||||

| Yes | 3.0 | 1,246.0 | 92 | 738.4 | 284.6 | 164.0, 459.3 |

| No | 97.0 | 50,981.3 | 714 | 140.1 | 120.5 | 111.2, 130.3 |

| Current hypertension | ||||||

| Yes | 20.2 | 9,886.8 | 344 | 347.9 | 140.2 | 121.3, 161.1 |

| No | 79.8 | 4,2340.5 | 462 | 109.1 | 121.0 | 109.6, 133.3 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married/common-law | 56.5 | 29,752.8 | 433 | 145.5 | 993.0 | 89.0, 110.4 |

| Widowed/separated/divorced/single, never married | 43.5 | 22,474.5 | 373 | 166.0 | 173.5 | 155.9, 192.5 |

| Misreporting status | ||||||

| Underreporter | 30.8 | 15,921.9 | 283 | 177.7 | 127.9 | 112.7, 144.6 |

| Plausible reporter | 57.3 | 29,944.3 | 470 | 157.0 | 129.5 | 117.0, 142.9 |

| Overreporter | 11.9 | 6,361.2 | 53 | 83.3 | 104.6 | 75.7, 140.7 |

| Immigration status | ||||||

| Canadian Born | 85.4 | 44,583.6 | 690 | 154.8 | 137.8 | 126.6, 149.6 |

| Immigrant | 14.6 | 7,643.7 | 116 | 151.8 | 86.9 | 70.1, 106.5 |

| Neighborhood deprivation indexb | ||||||

| Low | 12.7 | 6,614.2 | 95 | 143.6 | 317.3 | 88.5, 802.9 |

| Moderate | 70.0 | 36,695.2 | 545 | 148.5 | 119.8 | 109.4, 130.9 |

| High | 17.3 | 8,918.0 | 166 | 186.1 | 169.1 | 143.6, 197.8 |

| Self-perceived health | ||||||

| Poor | 3.7 | 1,573.2 | 105 | 667.4 | 373.7 | 299.1, 461.3 |

| Fair | 12.0 | 5,795.2 | 207 | 357.2 | 192.9 | 163.9, 225.6 |

| Good | 31.7 | 16,586.9 | 251 | 151.3 | 122.2 | 104.4, 142.3 |

| Very good | 34.0 | 18,234.4 | 172 | 94.3 | 91.4 | 77.5, 107.0 |

| Excellent | 18.6 | 10,037.5 | 71 | 70.7 | 78.8 | 60.9, 100.4 |

| Self-perceived stress | ||||||

| Not at all stressful | 14.6 | 7,223.8 | 224 | 310.1 | 134.8 | 113.9, 158.4 |

| Not very stressful | 26.1 | 1,3588.0 | 246 | 181.0 | 111.6 | 96.0, 128.9 |

| A bit stressful | 38.4 | 20,321.9 | 242 | 119.1 | 134.8 | 116.1, 155.6 |

| Quite a bit stressful | 17.7 | 9,387.5 | 78 | 83.1 | 154.6 | 114.1, 204.7 |

| Extremely stressful | 3.2 | 1,706.1 | 16 | 93.8 | 119.3 | 61.7, 208.2 |

| Sense of belonging to local community | ||||||

| Very strong | 22.5 | 11,696.5 | 215 | 183.8 | 109.8 | 94.2, 127.3 |

| Somewhat strong | 41.4 | 21,748.0 | 315 | 144.8 | 118.9 | 104.9, 134.2 |

| Somewhat weak | 23.9 | 12,489.5 | 171 | 136.9 | 144.1 | 122.7, 168.0 |

| Very weak | 12.2 | 6,293.4 | 105 | 166.8 | 160.4 | 130.3, 195.2 |

| Household food security status | ||||||

| Food secure | 93.3 | 48,681.1 | 773 | 158.8 | 123.4 | 114.3, 133.1 |

| Food insecure without hunger | 3.5 | 1,831.6 | 21 | 114.7 | 151.1 | 78.8, 262.3 |

| Food insecure with moderate/severe hunger | 2.7 | 1,486.6 | 12 | 80.7 | 119.6 | 44.7, 257.8 |

| Not stated | 0.4 | 228.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Variable . | Frequency, % . | Person-Years . | No. of Deaths . | Crude Mortality Rate, Per 10,000 Person-Years . | Age-Standardized Rate . | 95% CI . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline age categories, years | 100 | 52,227.3 | 806 | 154.3 | 126.3 | 117.2, 136.0 |

| <45 | 39.4 | 21,609.1 | 25 | 11.6 | ||

| 45–80 | 55.3 | 28,605.6 | 550 | 192.3 | ||

| ≥80 | 5.3 | 2,012.7 | 231 | 1,147.7 | ||

| Age categories, 10-year intervals | ||||||

| <30 | 18.1 | 9,888.6 | 7 | 7.1 | ||

| 30–39 | 13.1 | 7,198.7 | 8 | 11.1 | ||

| 40–49 | 17.5 | 9,572.2 | 30 | 31.3 | ||

| 50–59 | 18.5 | 10,023.5 | 60 | 59.9 | ||

| 60–69 | 13.0 | 6,679.2 | 140 | 209.6 | ||

| 70–79 | 13.5 | 6,372.9 | 298 | 467.6 | ||

| 80–89 | 5.9 | 2,363.8 | 238 | 1,006.8 | ||

| ≥90 | 0.5 | 128.5 | 25 | 1,945.4 | ||

| Dietary reference intake age groups, years | ||||||

| 19–30 | 19.5 | 10,667.2 | 8 | 7.5 | ||

| 31–50 | 31.2 | 17,116.5 | 40 | 23.4 | ||

| 51–70 | 30.7 | 16,194.5 | 213 | 131.5 | ||

| ≥71 | 18.6 | 8,249.2 | 545 | 660.7 | ||

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Daily/occasional smoker with with ≥20 but <90 cigarettes/day | 11.8 | 6,153.3 | 98 | 159.3 | 240.3 | 187.1, 303.9 |

| Daily/occasional smoker with <20 cigarettes/day | 16.7 | 8,834.1 | 86 | 97.4 | 223.7 | 164.2, 297.6 |

| Former daily/occasional smoker and those who smoked a total of ≥100 cigarettes in lifetime | 36.9 | 18,733.4 | 454 | 242.4 | 121.1 | 108.3, 134.9 |

| Never smoked | 34.6 | 18,506.5 | 168 | 90.8 | 94.3 | 80.0, 110.4 |

| Alcohol consumption over the prior 12 months | ||||||

| None | 16.9 | 8,341.7 | 261 | 312.9 | 159.8 | 139.2, 182.6 |

| Less than 1–3 times per month | 31.8 | 16,697.4 | 248 | 148.5 | 132.2 | 114.6, 151.7 |

| 1–3 times per week | 29.3 | 15,726.5 | 127 | 80.8 | 100.0 | 76.8, 127.9 |

| 4–7 times a week or being binge drinker: drank >2 times per week with the frequency of ≥5 drinks being 1 or more times per week | 22.0 | 11,461.7 | 170 | 1,483.0 | 122.8 | 100.3, 148.9 |

| Physical activity, metabolic equivalents/day | ||||||

| ≥3.0 | 19.7 | 10,491.7 | 97 | 92.5 | 837.0 | 65.5, 105.4 |

| 1.5–3.0 | 24.5 | 13,055.9 | 137 | 104.9 | 965.0 | 75.5, 121.5 |

| <1.5 | 55.8 | 28,679.8 | 572 | 199.4 | 148.8 | 136.3, 162.0 |

| Body mass indexa | ||||||

| <18.5 | 1.1 | 449.2 | 27 | 601.1 | 391.2 | 248.3, 586.4 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 29.4 | 15,139.5 | 285 | 188.3 | 142.3 | 125.6, 160.7 |

| 25.0–29.9 | 40.4 | 21,159.8 | 315 | 148.9 | 117.1 | 102.6, 133.0 |

| ≥30.0 | 29.1 | 15,478.8 | 179 | 115.6 | 129.1 | 105.1, 157.1 |

| Respondent’s highest level of education | ||||||

| Less than secondary school graduation | 26.4 | 13,122.8 | 398 | 303.3 | 148.6 | 131.9, 166.7 |

| Secondary school graduation | 16.6 | 8,833.2 | 80 | 90.6 | 117.2 | 83.0, 160.8 |

| Some postsecondary education | 8.8 | 4,642.2 | 53 | 114.2 | 133.3 | 98.9, 175.8 |

| Postsecondary graduation | 48.2 | 25,629.1 | 275 | 107.3 | 115.9 | 101.4, 132.0 |

| Current diabetes | ||||||

| Yes | 8.4 | 4,057.0 | 151 | 372.2 | 156.5 | 127.6, 190.0 |

| No | 91.6 | 48,170.3 | 655 | 136.0 | 120.7 | 111.1, 130.9 |

| Current heart disease | ||||||

| Yes | 10.3 | 4,712.0 | 250 | 530.6 | 161.6 | 138.5, 187.5 |

| No | 89.7 | 47,515.3 | 556 | 117.0 | 118.0 | 107.6, 129.3 |

| Current cancer | ||||||

| Yes | 3.0 | 1,246.0 | 92 | 738.4 | 284.6 | 164.0, 459.3 |

| No | 97.0 | 50,981.3 | 714 | 140.1 | 120.5 | 111.2, 130.3 |

| Current hypertension | ||||||

| Yes | 20.2 | 9,886.8 | 344 | 347.9 | 140.2 | 121.3, 161.1 |

| No | 79.8 | 4,2340.5 | 462 | 109.1 | 121.0 | 109.6, 133.3 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married/common-law | 56.5 | 29,752.8 | 433 | 145.5 | 993.0 | 89.0, 110.4 |

| Widowed/separated/divorced/single, never married | 43.5 | 22,474.5 | 373 | 166.0 | 173.5 | 155.9, 192.5 |

| Misreporting status | ||||||

| Underreporter | 30.8 | 15,921.9 | 283 | 177.7 | 127.9 | 112.7, 144.6 |

| Plausible reporter | 57.3 | 29,944.3 | 470 | 157.0 | 129.5 | 117.0, 142.9 |

| Overreporter | 11.9 | 6,361.2 | 53 | 83.3 | 104.6 | 75.7, 140.7 |

| Immigration status | ||||||

| Canadian Born | 85.4 | 44,583.6 | 690 | 154.8 | 137.8 | 126.6, 149.6 |

| Immigrant | 14.6 | 7,643.7 | 116 | 151.8 | 86.9 | 70.1, 106.5 |

| Neighborhood deprivation indexb | ||||||

| Low | 12.7 | 6,614.2 | 95 | 143.6 | 317.3 | 88.5, 802.9 |

| Moderate | 70.0 | 36,695.2 | 545 | 148.5 | 119.8 | 109.4, 130.9 |

| High | 17.3 | 8,918.0 | 166 | 186.1 | 169.1 | 143.6, 197.8 |

| Self-perceived health | ||||||

| Poor | 3.7 | 1,573.2 | 105 | 667.4 | 373.7 | 299.1, 461.3 |

| Fair | 12.0 | 5,795.2 | 207 | 357.2 | 192.9 | 163.9, 225.6 |

| Good | 31.7 | 16,586.9 | 251 | 151.3 | 122.2 | 104.4, 142.3 |

| Very good | 34.0 | 18,234.4 | 172 | 94.3 | 91.4 | 77.5, 107.0 |

| Excellent | 18.6 | 10,037.5 | 71 | 70.7 | 78.8 | 60.9, 100.4 |

| Self-perceived stress | ||||||

| Not at all stressful | 14.6 | 7,223.8 | 224 | 310.1 | 134.8 | 113.9, 158.4 |

| Not very stressful | 26.1 | 1,3588.0 | 246 | 181.0 | 111.6 | 96.0, 128.9 |

| A bit stressful | 38.4 | 20,321.9 | 242 | 119.1 | 134.8 | 116.1, 155.6 |

| Quite a bit stressful | 17.7 | 9,387.5 | 78 | 83.1 | 154.6 | 114.1, 204.7 |

| Extremely stressful | 3.2 | 1,706.1 | 16 | 93.8 | 119.3 | 61.7, 208.2 |

| Sense of belonging to local community | ||||||

| Very strong | 22.5 | 11,696.5 | 215 | 183.8 | 109.8 | 94.2, 127.3 |

| Somewhat strong | 41.4 | 21,748.0 | 315 | 144.8 | 118.9 | 104.9, 134.2 |

| Somewhat weak | 23.9 | 12,489.5 | 171 | 136.9 | 144.1 | 122.7, 168.0 |

| Very weak | 12.2 | 6,293.4 | 105 | 166.8 | 160.4 | 130.3, 195.2 |

| Household food security status | ||||||

| Food secure | 93.3 | 48,681.1 | 773 | 158.8 | 123.4 | 114.3, 133.1 |

| Food insecure without hunger | 3.5 | 1,831.6 | 21 | 114.7 | 151.1 | 78.8, 262.3 |

| Food insecure with moderate/severe hunger | 2.7 | 1,486.6 | 12 | 80.7 | 119.6 | 44.7, 257.8 |

| Not stated | 0.4 | 228.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

a Body mass index calculated as weight (kg)/height (m)2.

b An area-based deprivation index was used that categorizes dissemination areas (smallest geostatistical units of Canadian census) into 2 sets of quintile groups: one for the social components of deprivation (% of people living alone, % of people divorced/separated, and % of single-parent families) and one for the material components (% without high school graduation, employment ratio, and the average income). Quintile 1 in each group represents the 20% least deprived while quintile 5 represents the 20% most deprived; when cross-tabulated, these quintiles create 25 distinct cells. We defined “low neighborhood deprivation” as dissemination areas with social and material combinations in quintiles 1 and 2 (4 cells) and “high neighborhood deprivation” as dissemination areas with social and material combinations in quintiles 4 and 5 (4 cells). The remaining dissemination areas (17 cells) were classified as having “moderate neighborhood deprivation” (57, 58).

Baseline Characteristics and Crude Mortality Rates per 10,000 Person-Years (Unweighted) Among Men (n = 7,355), Canadian Adults in Canadian Community Health Survey–Nutrition Linked to Canadian Vital Statistics Death Database, 2004/2005 to 2011

| Variable . | Frequency, % . | Person-Years . | No. of Deaths . | Crude Mortality Rate, Per 10,000 Person-Years . | Age-Standardized Rate . | 95% CI . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline age categories, years | 100 | 52,227.3 | 806 | 154.3 | 126.3 | 117.2, 136.0 |

| <45 | 39.4 | 21,609.1 | 25 | 11.6 | ||

| 45–80 | 55.3 | 28,605.6 | 550 | 192.3 | ||

| ≥80 | 5.3 | 2,012.7 | 231 | 1,147.7 | ||

| Age categories, 10-year intervals | ||||||

| <30 | 18.1 | 9,888.6 | 7 | 7.1 | ||

| 30–39 | 13.1 | 7,198.7 | 8 | 11.1 | ||

| 40–49 | 17.5 | 9,572.2 | 30 | 31.3 | ||

| 50–59 | 18.5 | 10,023.5 | 60 | 59.9 | ||

| 60–69 | 13.0 | 6,679.2 | 140 | 209.6 | ||

| 70–79 | 13.5 | 6,372.9 | 298 | 467.6 | ||

| 80–89 | 5.9 | 2,363.8 | 238 | 1,006.8 | ||

| ≥90 | 0.5 | 128.5 | 25 | 1,945.4 | ||

| Dietary reference intake age groups, years | ||||||

| 19–30 | 19.5 | 10,667.2 | 8 | 7.5 | ||

| 31–50 | 31.2 | 17,116.5 | 40 | 23.4 | ||

| 51–70 | 30.7 | 16,194.5 | 213 | 131.5 | ||

| ≥71 | 18.6 | 8,249.2 | 545 | 660.7 | ||

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Daily/occasional smoker with with ≥20 but <90 cigarettes/day | 11.8 | 6,153.3 | 98 | 159.3 | 240.3 | 187.1, 303.9 |

| Daily/occasional smoker with <20 cigarettes/day | 16.7 | 8,834.1 | 86 | 97.4 | 223.7 | 164.2, 297.6 |

| Former daily/occasional smoker and those who smoked a total of ≥100 cigarettes in lifetime | 36.9 | 18,733.4 | 454 | 242.4 | 121.1 | 108.3, 134.9 |

| Never smoked | 34.6 | 18,506.5 | 168 | 90.8 | 94.3 | 80.0, 110.4 |

| Alcohol consumption over the prior 12 months | ||||||

| None | 16.9 | 8,341.7 | 261 | 312.9 | 159.8 | 139.2, 182.6 |

| Less than 1–3 times per month | 31.8 | 16,697.4 | 248 | 148.5 | 132.2 | 114.6, 151.7 |

| 1–3 times per week | 29.3 | 15,726.5 | 127 | 80.8 | 100.0 | 76.8, 127.9 |

| 4–7 times a week or being binge drinker: drank >2 times per week with the frequency of ≥5 drinks being 1 or more times per week | 22.0 | 11,461.7 | 170 | 1,483.0 | 122.8 | 100.3, 148.9 |

| Physical activity, metabolic equivalents/day | ||||||

| ≥3.0 | 19.7 | 10,491.7 | 97 | 92.5 | 837.0 | 65.5, 105.4 |

| 1.5–3.0 | 24.5 | 13,055.9 | 137 | 104.9 | 965.0 | 75.5, 121.5 |

| <1.5 | 55.8 | 28,679.8 | 572 | 199.4 | 148.8 | 136.3, 162.0 |

| Body mass indexa | ||||||

| <18.5 | 1.1 | 449.2 | 27 | 601.1 | 391.2 | 248.3, 586.4 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 29.4 | 15,139.5 | 285 | 188.3 | 142.3 | 125.6, 160.7 |

| 25.0–29.9 | 40.4 | 21,159.8 | 315 | 148.9 | 117.1 | 102.6, 133.0 |

| ≥30.0 | 29.1 | 15,478.8 | 179 | 115.6 | 129.1 | 105.1, 157.1 |

| Respondent’s highest level of education | ||||||

| Less than secondary school graduation | 26.4 | 13,122.8 | 398 | 303.3 | 148.6 | 131.9, 166.7 |

| Secondary school graduation | 16.6 | 8,833.2 | 80 | 90.6 | 117.2 | 83.0, 160.8 |

| Some postsecondary education | 8.8 | 4,642.2 | 53 | 114.2 | 133.3 | 98.9, 175.8 |

| Postsecondary graduation | 48.2 | 25,629.1 | 275 | 107.3 | 115.9 | 101.4, 132.0 |

| Current diabetes | ||||||

| Yes | 8.4 | 4,057.0 | 151 | 372.2 | 156.5 | 127.6, 190.0 |

| No | 91.6 | 48,170.3 | 655 | 136.0 | 120.7 | 111.1, 130.9 |

| Current heart disease | ||||||

| Yes | 10.3 | 4,712.0 | 250 | 530.6 | 161.6 | 138.5, 187.5 |

| No | 89.7 | 47,515.3 | 556 | 117.0 | 118.0 | 107.6, 129.3 |

| Current cancer | ||||||

| Yes | 3.0 | 1,246.0 | 92 | 738.4 | 284.6 | 164.0, 459.3 |

| No | 97.0 | 50,981.3 | 714 | 140.1 | 120.5 | 111.2, 130.3 |

| Current hypertension | ||||||

| Yes | 20.2 | 9,886.8 | 344 | 347.9 | 140.2 | 121.3, 161.1 |

| No | 79.8 | 4,2340.5 | 462 | 109.1 | 121.0 | 109.6, 133.3 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married/common-law | 56.5 | 29,752.8 | 433 | 145.5 | 993.0 | 89.0, 110.4 |

| Widowed/separated/divorced/single, never married | 43.5 | 22,474.5 | 373 | 166.0 | 173.5 | 155.9, 192.5 |

| Misreporting status | ||||||

| Underreporter | 30.8 | 15,921.9 | 283 | 177.7 | 127.9 | 112.7, 144.6 |

| Plausible reporter | 57.3 | 29,944.3 | 470 | 157.0 | 129.5 | 117.0, 142.9 |

| Overreporter | 11.9 | 6,361.2 | 53 | 83.3 | 104.6 | 75.7, 140.7 |

| Immigration status | ||||||

| Canadian Born | 85.4 | 44,583.6 | 690 | 154.8 | 137.8 | 126.6, 149.6 |

| Immigrant | 14.6 | 7,643.7 | 116 | 151.8 | 86.9 | 70.1, 106.5 |

| Neighborhood deprivation indexb | ||||||

| Low | 12.7 | 6,614.2 | 95 | 143.6 | 317.3 | 88.5, 802.9 |

| Moderate | 70.0 | 36,695.2 | 545 | 148.5 | 119.8 | 109.4, 130.9 |

| High | 17.3 | 8,918.0 | 166 | 186.1 | 169.1 | 143.6, 197.8 |

| Self-perceived health | ||||||

| Poor | 3.7 | 1,573.2 | 105 | 667.4 | 373.7 | 299.1, 461.3 |

| Fair | 12.0 | 5,795.2 | 207 | 357.2 | 192.9 | 163.9, 225.6 |

| Good | 31.7 | 16,586.9 | 251 | 151.3 | 122.2 | 104.4, 142.3 |

| Very good | 34.0 | 18,234.4 | 172 | 94.3 | 91.4 | 77.5, 107.0 |

| Excellent | 18.6 | 10,037.5 | 71 | 70.7 | 78.8 | 60.9, 100.4 |

| Self-perceived stress | ||||||

| Not at all stressful | 14.6 | 7,223.8 | 224 | 310.1 | 134.8 | 113.9, 158.4 |

| Not very stressful | 26.1 | 1,3588.0 | 246 | 181.0 | 111.6 | 96.0, 128.9 |

| A bit stressful | 38.4 | 20,321.9 | 242 | 119.1 | 134.8 | 116.1, 155.6 |

| Quite a bit stressful | 17.7 | 9,387.5 | 78 | 83.1 | 154.6 | 114.1, 204.7 |

| Extremely stressful | 3.2 | 1,706.1 | 16 | 93.8 | 119.3 | 61.7, 208.2 |

| Sense of belonging to local community | ||||||

| Very strong | 22.5 | 11,696.5 | 215 | 183.8 | 109.8 | 94.2, 127.3 |

| Somewhat strong | 41.4 | 21,748.0 | 315 | 144.8 | 118.9 | 104.9, 134.2 |

| Somewhat weak | 23.9 | 12,489.5 | 171 | 136.9 | 144.1 | 122.7, 168.0 |

| Very weak | 12.2 | 6,293.4 | 105 | 166.8 | 160.4 | 130.3, 195.2 |

| Household food security status | ||||||

| Food secure | 93.3 | 48,681.1 | 773 | 158.8 | 123.4 | 114.3, 133.1 |

| Food insecure without hunger | 3.5 | 1,831.6 | 21 | 114.7 | 151.1 | 78.8, 262.3 |

| Food insecure with moderate/severe hunger | 2.7 | 1,486.6 | 12 | 80.7 | 119.6 | 44.7, 257.8 |

| Not stated | 0.4 | 228.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Variable . | Frequency, % . | Person-Years . | No. of Deaths . | Crude Mortality Rate, Per 10,000 Person-Years . | Age-Standardized Rate . | 95% CI . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline age categories, years | 100 | 52,227.3 | 806 | 154.3 | 126.3 | 117.2, 136.0 |

| <45 | 39.4 | 21,609.1 | 25 | 11.6 | ||

| 45–80 | 55.3 | 28,605.6 | 550 | 192.3 | ||

| ≥80 | 5.3 | 2,012.7 | 231 | 1,147.7 | ||

| Age categories, 10-year intervals | ||||||

| <30 | 18.1 | 9,888.6 | 7 | 7.1 | ||

| 30–39 | 13.1 | 7,198.7 | 8 | 11.1 | ||

| 40–49 | 17.5 | 9,572.2 | 30 | 31.3 | ||

| 50–59 | 18.5 | 10,023.5 | 60 | 59.9 | ||

| 60–69 | 13.0 | 6,679.2 | 140 | 209.6 | ||

| 70–79 | 13.5 | 6,372.9 | 298 | 467.6 | ||

| 80–89 | 5.9 | 2,363.8 | 238 | 1,006.8 | ||

| ≥90 | 0.5 | 128.5 | 25 | 1,945.4 | ||

| Dietary reference intake age groups, years | ||||||

| 19–30 | 19.5 | 10,667.2 | 8 | 7.5 | ||

| 31–50 | 31.2 | 17,116.5 | 40 | 23.4 | ||

| 51–70 | 30.7 | 16,194.5 | 213 | 131.5 | ||

| ≥71 | 18.6 | 8,249.2 | 545 | 660.7 | ||

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Daily/occasional smoker with with ≥20 but <90 cigarettes/day | 11.8 | 6,153.3 | 98 | 159.3 | 240.3 | 187.1, 303.9 |

| Daily/occasional smoker with <20 cigarettes/day | 16.7 | 8,834.1 | 86 | 97.4 | 223.7 | 164.2, 297.6 |

| Former daily/occasional smoker and those who smoked a total of ≥100 cigarettes in lifetime | 36.9 | 18,733.4 | 454 | 242.4 | 121.1 | 108.3, 134.9 |

| Never smoked | 34.6 | 18,506.5 | 168 | 90.8 | 94.3 | 80.0, 110.4 |

| Alcohol consumption over the prior 12 months | ||||||

| None | 16.9 | 8,341.7 | 261 | 312.9 | 159.8 | 139.2, 182.6 |

| Less than 1–3 times per month | 31.8 | 16,697.4 | 248 | 148.5 | 132.2 | 114.6, 151.7 |

| 1–3 times per week | 29.3 | 15,726.5 | 127 | 80.8 | 100.0 | 76.8, 127.9 |

| 4–7 times a week or being binge drinker: drank >2 times per week with the frequency of ≥5 drinks being 1 or more times per week | 22.0 | 11,461.7 | 170 | 1,483.0 | 122.8 | 100.3, 148.9 |

| Physical activity, metabolic equivalents/day | ||||||

| ≥3.0 | 19.7 | 10,491.7 | 97 | 92.5 | 837.0 | 65.5, 105.4 |

| 1.5–3.0 | 24.5 | 13,055.9 | 137 | 104.9 | 965.0 | 75.5, 121.5 |

| <1.5 | 55.8 | 28,679.8 | 572 | 199.4 | 148.8 | 136.3, 162.0 |

| Body mass indexa | ||||||

| <18.5 | 1.1 | 449.2 | 27 | 601.1 | 391.2 | 248.3, 586.4 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 29.4 | 15,139.5 | 285 | 188.3 | 142.3 | 125.6, 160.7 |

| 25.0–29.9 | 40.4 | 21,159.8 | 315 | 148.9 | 117.1 | 102.6, 133.0 |

| ≥30.0 | 29.1 | 15,478.8 | 179 | 115.6 | 129.1 | 105.1, 157.1 |

| Respondent’s highest level of education | ||||||

| Less than secondary school graduation | 26.4 | 13,122.8 | 398 | 303.3 | 148.6 | 131.9, 166.7 |

| Secondary school graduation | 16.6 | 8,833.2 | 80 | 90.6 | 117.2 | 83.0, 160.8 |

| Some postsecondary education | 8.8 | 4,642.2 | 53 | 114.2 | 133.3 | 98.9, 175.8 |

| Postsecondary graduation | 48.2 | 25,629.1 | 275 | 107.3 | 115.9 | 101.4, 132.0 |

| Current diabetes | ||||||

| Yes | 8.4 | 4,057.0 | 151 | 372.2 | 156.5 | 127.6, 190.0 |

| No | 91.6 | 48,170.3 | 655 | 136.0 | 120.7 | 111.1, 130.9 |

| Current heart disease | ||||||

| Yes | 10.3 | 4,712.0 | 250 | 530.6 | 161.6 | 138.5, 187.5 |

| No | 89.7 | 47,515.3 | 556 | 117.0 | 118.0 | 107.6, 129.3 |

| Current cancer | ||||||

| Yes | 3.0 | 1,246.0 | 92 | 738.4 | 284.6 | 164.0, 459.3 |

| No | 97.0 | 50,981.3 | 714 | 140.1 | 120.5 | 111.2, 130.3 |

| Current hypertension | ||||||

| Yes | 20.2 | 9,886.8 | 344 | 347.9 | 140.2 | 121.3, 161.1 |

| No | 79.8 | 4,2340.5 | 462 | 109.1 | 121.0 | 109.6, 133.3 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married/common-law | 56.5 | 29,752.8 | 433 | 145.5 | 993.0 | 89.0, 110.4 |

| Widowed/separated/divorced/single, never married | 43.5 | 22,474.5 | 373 | 166.0 | 173.5 | 155.9, 192.5 |

| Misreporting status | ||||||

| Underreporter | 30.8 | 15,921.9 | 283 | 177.7 | 127.9 | 112.7, 144.6 |

| Plausible reporter | 57.3 | 29,944.3 | 470 | 157.0 | 129.5 | 117.0, 142.9 |

| Overreporter | 11.9 | 6,361.2 | 53 | 83.3 | 104.6 | 75.7, 140.7 |

| Immigration status | ||||||

| Canadian Born | 85.4 | 44,583.6 | 690 | 154.8 | 137.8 | 126.6, 149.6 |

| Immigrant | 14.6 | 7,643.7 | 116 | 151.8 | 86.9 | 70.1, 106.5 |

| Neighborhood deprivation indexb | ||||||

| Low | 12.7 | 6,614.2 | 95 | 143.6 | 317.3 | 88.5, 802.9 |

| Moderate | 70.0 | 36,695.2 | 545 | 148.5 | 119.8 | 109.4, 130.9 |

| High | 17.3 | 8,918.0 | 166 | 186.1 | 169.1 | 143.6, 197.8 |

| Self-perceived health | ||||||

| Poor | 3.7 | 1,573.2 | 105 | 667.4 | 373.7 | 299.1, 461.3 |

| Fair | 12.0 | 5,795.2 | 207 | 357.2 | 192.9 | 163.9, 225.6 |

| Good | 31.7 | 16,586.9 | 251 | 151.3 | 122.2 | 104.4, 142.3 |

| Very good | 34.0 | 18,234.4 | 172 | 94.3 | 91.4 | 77.5, 107.0 |

| Excellent | 18.6 | 10,037.5 | 71 | 70.7 | 78.8 | 60.9, 100.4 |

| Self-perceived stress | ||||||

| Not at all stressful | 14.6 | 7,223.8 | 224 | 310.1 | 134.8 | 113.9, 158.4 |

| Not very stressful | 26.1 | 1,3588.0 | 246 | 181.0 | 111.6 | 96.0, 128.9 |

| A bit stressful | 38.4 | 20,321.9 | 242 | 119.1 | 134.8 | 116.1, 155.6 |

| Quite a bit stressful | 17.7 | 9,387.5 | 78 | 83.1 | 154.6 | 114.1, 204.7 |

| Extremely stressful | 3.2 | 1,706.1 | 16 | 93.8 | 119.3 | 61.7, 208.2 |

| Sense of belonging to local community | ||||||

| Very strong | 22.5 | 11,696.5 | 215 | 183.8 | 109.8 | 94.2, 127.3 |

| Somewhat strong | 41.4 | 21,748.0 | 315 | 144.8 | 118.9 | 104.9, 134.2 |

| Somewhat weak | 23.9 | 12,489.5 | 171 | 136.9 | 144.1 | 122.7, 168.0 |

| Very weak | 12.2 | 6,293.4 | 105 | 166.8 | 160.4 | 130.3, 195.2 |

| Household food security status | ||||||

| Food secure | 93.3 | 48,681.1 | 773 | 158.8 | 123.4 | 114.3, 133.1 |

| Food insecure without hunger | 3.5 | 1,831.6 | 21 | 114.7 | 151.1 | 78.8, 262.3 |

| Food insecure with moderate/severe hunger | 2.7 | 1,486.6 | 12 | 80.7 | 119.6 | 44.7, 257.8 |

| Not stated | 0.4 | 228.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

a Body mass index calculated as weight (kg)/height (m)2.

b An area-based deprivation index was used that categorizes dissemination areas (smallest geostatistical units of Canadian census) into 2 sets of quintile groups: one for the social components of deprivation (% of people living alone, % of people divorced/separated, and % of single-parent families) and one for the material components (% without high school graduation, employment ratio, and the average income). Quintile 1 in each group represents the 20% least deprived while quintile 5 represents the 20% most deprived; when cross-tabulated, these quintiles create 25 distinct cells. We defined “low neighborhood deprivation” as dissemination areas with social and material combinations in quintiles 1 and 2 (4 cells) and “high neighborhood deprivation” as dissemination areas with social and material combinations in quintiles 4 and 5 (4 cells). The remaining dissemination areas (17 cells) were classified as having “moderate neighborhood deprivation” (57, 58).

RESULTS

Within the 115,566 person-years of follow-up (median, 7.48 (interquartile range, 7.22–7.7) years), 1,722 deaths were recorded. The mean age at baseline and end of follow-up were, for men, 46.09 (standard error, 0.17) and 53.33 (standard error, 0.17) and, for women, 47.97 (standard error, 0.34) and 55.31 (standard error, 0.34), respectively. Baseline characteristics and crude and age-standardized mortality rates for sociodemographic and lifestyle behaviors are presented in Tables 1 and 2. Among men, being underweight (body mass index < 18.50) was associated with the highest age-standardized mortality rate per 10,000 person-years (391.2, 95% CI: 248.3, 586.4), while in women, being a daily/occasional smoker with 20–90 cigarettes per day was associated with the highest age-standardized mortality rate per 10,000 person-years (351.7, 95% CI: 80.1, 982.6). As expected, favorable lifestyle behavior and sociodemographic exposure categories resulted in the lowest age-standardized mortality rates (e.g., never or less frequent smoking, moderate alcohol consumption, greater physical activity, higher education, better self-perceived health, and a greater sense of belonging to the local community).

Baseline Characteristics and Crude Mortality Rates per 10,000 Person-Years (Unweighted) Among Women (n = 8,857), Canadian Adults in Canadian Community Health Survey–Nutrition Linked to Canadian Vital Statistics Death Database, 2004/2005 to 2011

| Variable . | Frequency, % . | Person-Years . | No. of Deaths . | Crude Mortality Rate, Per 10,000 Person-Years . | Age-Standardized Rate . | 95% CI . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline age categories, years | 100 | 63,338.9 | 916 | 144.6 | 84.2 | 78.5, 90.2 |

| <45 | 33.3 | 22,087.6 | 16 | 7.2 | ||

| 45–80 | 57.6 | 36,569.5 | 520 | 142.2 | ||

| ≥80 | 9.1 | 4,681.8 | 380 | 811.7 | ||

| Age categories, 10-year intervals | ||||||

| <30 | 15.6 | 10,341.3 | 5 | 4.8 | ||

| 30–39 | 11.1 | 7,380.9 | 5 | 6.8 | ||

| 40–49 | 15.1 | 9,994.0 | 19 | 19.0 | ||

| 50–59 | 17.4 | 11,333.6 | 61 | 53.8 | ||

| 60–69 | 14.0 | 8,924.1 | 115 | 128.9 | ||

| 70–79 | 16.2 | 9,776.1 | 288 | 294.6 | ||

| 80–89 | 9.6 | 5,141.4 | 361 | 702.1 | ||

| ≥90 | 1.1 | 447.5 | 62 | 1,385.5 | ||

| Dietary reference intake age groups, years | ||||||

| <31 | 16.9 | 11,196.7 | 6 | 5.4 | ||

| 31–50 | 26.6 | 17,651.8 | 25 | 14.2 | ||

| 51–70 | 31.0 | 19,965.7 | 187 | 93.7 | ||

| ≥71 | 25.5 | 14,524.8 | 698 | 480.6 | ||

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Daily/occasional smoker with ≥20 but >90 cigarettes/day | 6.0 | 3,822.6 | 55 | 143.9 | 351.7 | 80.1, 982.6 |

| Daily/occasional smoker with <20 cigarettes/day | 17.3 | 11,098.0 | 110 | 99.1 | 121.7 | 99.4, 147.5 |

| Former daily/occasional smoker and those who smoked a total of ≥100 cigarettes in lifetime | 27.5 | 17,315.7 | 270 | 155.9 | 81.4 | 71.4, 92.4 |

| Never smoked | 49.2 | 31,102.5 | 481 | 154.7 | 70.1 | 63.2, 77.7 |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||||

| None | 8.6 | 16,275.6 | 441 | 271.0 | 103.0 | 90.7, 116.5 |

| Less than 1–3 times per month | 26.8 | 27,776.6 | 308 | 110.9 | 77.9 | 68.9, 87.7 |

| 1–3 times per week | 43.3 | 13,867.5 | 85 | 61.3 | 67.9 | 51.1, 88.4 |

| 4–7 times a week or being binge drinker: drank >2 times per week with the frequency of ≥5 drinks being 1 or more times per week | 21.3 | 5,419.2 | 82 | 151.3 | 81.1 | 63.0, 102.7 |

| Physical activity, metabolic equivalents/day | ||||||

| ≥3.0 | 15.8 | 10,232.7 | 63 | 61.6 | 62.6 | 45.6, 83.8 |

| 1.5–3.0 | 23.7 | 15,284.8 | 123 | 80.5 | 64.3 | 52.0, 78.7 |

| <1.5 | 60.6 | 37,821.5 | 730 | 193.0 | 95.2 | 87.7, 103.1 |

| Body mass indexa | ||||||

| <18.5 | 2.2 | 1,292.8 | 37 | 286.2 | 167.7 | 105.0, 254.2 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 36.7 | 23,134.6 | 349 | 150.9 | 88.4 | 78.6, 99.1 |

| 25.0–29.9 | 32.2 | 20,405.3 | 286 | 140.2 | 73.0 | 64.1, 82.9 |

| ≥30.0 | 29.0 | 18,506.2 | 244 | 131.9 | 87.6 | 76.0, 100.5 |

| Respondent’s highest level of education | ||||||

| Less than secondary school graduation | 28.6 | 17,362.1 | 487 | 280.5 | 102.9 | 88.8, 118.5 |

| Secondary school graduation | 17.5 | 11,118.8 | 138 | 124.1 | 87.8 | 72.4, 105.5 |

| Some postsecondary education | 8.2 | 5,269.9 | 49 | 93.0 | 87.4 | 64.2, 116.4 |

| Postsecondary graduation | 45.7 | 29,588.1 | 242 | 81.8 | 73.6 | 64.4, 83.8 |

| Current diabetes | ||||||

| Yes | 8.0 | 4,675.1 | 171 | 365.8 | 154.7 | 115.2, 203.4 |

| No | 92.0 | 58,663.8 | 745 | 127.0 | 77.0 | 71.2, 83.1 |

| Current heart disease | ||||||

| Yes | 8.5 | 4,684.0 | 253 | 540.1 | 130.0 | 106.4, 157.4 |

| No | 91.5 | 58,654.9 | 663 | 113.0 | 75.6 | 69.6, 81.9 |

| Current cancer | ||||||

| Yes | 2.6 | 1,410.4 | 76 | 538.8 | 191.3 | 143.9, 249.3 |

| No | 97.4 | 61,928.5 | 840 | 135.6 | 80.5 | 74.8, 86.6 |

| Current hypertension | ||||||

| Yes | 25.6 | 15,435.3 | 454 | 294.1 | 92.8 | 81.0, 105.9 |

| No | 74.4 | 47,903.6 | 462 | 96.4 | 79.0 | 71.8, 86.7 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married/common-law | 47.5 | 30,819.2 | 233 | 75.6 | 66.0 | 56.5, 76.6 |

| Widowed/separated/divorced/single, never married | 52.6 | 32,519.7 | 683 | 210.0 | 98.2 | 89.3, 107.7 |

| Misreporting status | ||||||

| Underreporter | 34.4 | 21,804.4 | 311 | 142.6 | 91.4 | 80.9, 103.0 |

| Plausible reporter | 56.5 | 35,719.3 | 523 | 146.4 | 80.5 | 73.3, 88.3 |

| Overreporter | 9.1 | 5,815.2 | 82 | 141.0 | 83.4 | 65.4, 104.8 |

| Immigration status | ||||||

| Canadian born | 85.7 | 54,301.2 | 786 | 144.8 | 90.6 | 84.1, 97.6 |

| Immigrant | 14.3 | 9,037.7 | 130 | 143.8 | 53.0 | 43.3, 64.3 |

| Neighborhood deprivation indexb | ||||||

| Low | 11.6 | 7,360.3 | 95 | 129.1 | 73.3 | 58.6, 90.6 |

| Moderate | 68.1 | 43,206.1 | 604 | 139.8 | 82.5 | 75.5, 89.9 |

| High | 20.3 | 12,772.6 | 217 | 169.9 | 97.1 | 83.7, 112.1 |

| Self-perceived health | ||||||

| Poor | 4.2 | 2,380.8 | 97 | 407.4 | 200.3 | 155.5, 254.0 |

| Fair | 13.1 | 7,753.9 | 262 | 337.9 | 150.5 | 129.2, 174.2 |

| Good | 31.6 | 19,970.5 | 297 | 148.7 | 80.3 | 70.1, 91.6 |

| Very good | 34.7 | 2,2403.8 | 209 | 93.3 | 61.3 | 53.0, 70.5 |

| Excellent | 16.6 | 10,829.8 | 51 | 47.1 | 42.9 | 31.6, 57.0 |

| Self-perceived stress | ||||||

| Not at all stressful | 12.6 | 7,705.5 | 202 | 262.2 | 83.9 | 65.5, 106.0 |

| Not very stressful | 25.7 | 16,056.6 | 295 | 183.7 | 77.2 | 67.9, 87.5 |

| A bit stressful | 39.8 | 25,462.3 | 298 | 117.0 | 87.9 | 77.7, 99.0 |

| Quite a bit stressful | 18.2 | 11,739.7 | 96 | 81.8 | 90.4 | 72.1, 111.9 |

| Extremely stressful | 3.7 | 2,374.8 | 25 | 105.3 | 133.4 | 85.1, 199.2 |

| Sense of belonging to local community | ||||||

| Very strong | 25.3 | 15,883.1 | 281 | 176.9 | 73.9 | 64.6, 84.1 |

| Somewhat strong | 40.9 | 26,118.4 | 328 | 125.6 | 82.7 | 73.4, 92.8 |

| Somewhat weak | 22.2 | 14,099.7 | 181 | 128.4 | 88.5 | 75.6, 103.0 |

| Very weak | 11.6 | 7,237.7 | 126 | 174.1 | 120.1 | 98.6, 145.0 |

| Household food security status | ||||||

| Food secure | 91.9 | 58,030.8 | 885 | 152.5 | 82.8 | 77.0, 88.8 |

| Food insecure without hunger | 4.8 | 3,159.6 | 17 | 53.8 | 75.5 | 42.4, 124.3 |

| Food insecure with moderate/severe hunger | 3.1 | 2,022.5 | 14 | 69.2 | 137.5 | 37.2, 353.2 |

| Not stated | 0.2 | 126.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Variable . | Frequency, % . | Person-Years . | No. of Deaths . | Crude Mortality Rate, Per 10,000 Person-Years . | Age-Standardized Rate . | 95% CI . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline age categories, years | 100 | 63,338.9 | 916 | 144.6 | 84.2 | 78.5, 90.2 |

| <45 | 33.3 | 22,087.6 | 16 | 7.2 | ||

| 45–80 | 57.6 | 36,569.5 | 520 | 142.2 | ||

| ≥80 | 9.1 | 4,681.8 | 380 | 811.7 | ||

| Age categories, 10-year intervals | ||||||

| <30 | 15.6 | 10,341.3 | 5 | 4.8 | ||

| 30–39 | 11.1 | 7,380.9 | 5 | 6.8 | ||

| 40–49 | 15.1 | 9,994.0 | 19 | 19.0 | ||

| 50–59 | 17.4 | 11,333.6 | 61 | 53.8 | ||

| 60–69 | 14.0 | 8,924.1 | 115 | 128.9 | ||

| 70–79 | 16.2 | 9,776.1 | 288 | 294.6 | ||

| 80–89 | 9.6 | 5,141.4 | 361 | 702.1 | ||

| ≥90 | 1.1 | 447.5 | 62 | 1,385.5 | ||

| Dietary reference intake age groups, years | ||||||

| <31 | 16.9 | 11,196.7 | 6 | 5.4 | ||

| 31–50 | 26.6 | 17,651.8 | 25 | 14.2 | ||

| 51–70 | 31.0 | 19,965.7 | 187 | 93.7 | ||

| ≥71 | 25.5 | 14,524.8 | 698 | 480.6 | ||

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Daily/occasional smoker with ≥20 but >90 cigarettes/day | 6.0 | 3,822.6 | 55 | 143.9 | 351.7 | 80.1, 982.6 |

| Daily/occasional smoker with <20 cigarettes/day | 17.3 | 11,098.0 | 110 | 99.1 | 121.7 | 99.4, 147.5 |

| Former daily/occasional smoker and those who smoked a total of ≥100 cigarettes in lifetime | 27.5 | 17,315.7 | 270 | 155.9 | 81.4 | 71.4, 92.4 |

| Never smoked | 49.2 | 31,102.5 | 481 | 154.7 | 70.1 | 63.2, 77.7 |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||||

| None | 8.6 | 16,275.6 | 441 | 271.0 | 103.0 | 90.7, 116.5 |

| Less than 1–3 times per month | 26.8 | 27,776.6 | 308 | 110.9 | 77.9 | 68.9, 87.7 |

| 1–3 times per week | 43.3 | 13,867.5 | 85 | 61.3 | 67.9 | 51.1, 88.4 |

| 4–7 times a week or being binge drinker: drank >2 times per week with the frequency of ≥5 drinks being 1 or more times per week | 21.3 | 5,419.2 | 82 | 151.3 | 81.1 | 63.0, 102.7 |

| Physical activity, metabolic equivalents/day | ||||||

| ≥3.0 | 15.8 | 10,232.7 | 63 | 61.6 | 62.6 | 45.6, 83.8 |

| 1.5–3.0 | 23.7 | 15,284.8 | 123 | 80.5 | 64.3 | 52.0, 78.7 |

| <1.5 | 60.6 | 37,821.5 | 730 | 193.0 | 95.2 | 87.7, 103.1 |

| Body mass indexa | ||||||

| <18.5 | 2.2 | 1,292.8 | 37 | 286.2 | 167.7 | 105.0, 254.2 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 36.7 | 23,134.6 | 349 | 150.9 | 88.4 | 78.6, 99.1 |

| 25.0–29.9 | 32.2 | 20,405.3 | 286 | 140.2 | 73.0 | 64.1, 82.9 |

| ≥30.0 | 29.0 | 18,506.2 | 244 | 131.9 | 87.6 | 76.0, 100.5 |

| Respondent’s highest level of education | ||||||

| Less than secondary school graduation | 28.6 | 17,362.1 | 487 | 280.5 | 102.9 | 88.8, 118.5 |

| Secondary school graduation | 17.5 | 11,118.8 | 138 | 124.1 | 87.8 | 72.4, 105.5 |

| Some postsecondary education | 8.2 | 5,269.9 | 49 | 93.0 | 87.4 | 64.2, 116.4 |

| Postsecondary graduation | 45.7 | 29,588.1 | 242 | 81.8 | 73.6 | 64.4, 83.8 |

| Current diabetes | ||||||

| Yes | 8.0 | 4,675.1 | 171 | 365.8 | 154.7 | 115.2, 203.4 |

| No | 92.0 | 58,663.8 | 745 | 127.0 | 77.0 | 71.2, 83.1 |

| Current heart disease | ||||||

| Yes | 8.5 | 4,684.0 | 253 | 540.1 | 130.0 | 106.4, 157.4 |

| No | 91.5 | 58,654.9 | 663 | 113.0 | 75.6 | 69.6, 81.9 |

| Current cancer | ||||||

| Yes | 2.6 | 1,410.4 | 76 | 538.8 | 191.3 | 143.9, 249.3 |

| No | 97.4 | 61,928.5 | 840 | 135.6 | 80.5 | 74.8, 86.6 |

| Current hypertension | ||||||

| Yes | 25.6 | 15,435.3 | 454 | 294.1 | 92.8 | 81.0, 105.9 |

| No | 74.4 | 47,903.6 | 462 | 96.4 | 79.0 | 71.8, 86.7 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married/common-law | 47.5 | 30,819.2 | 233 | 75.6 | 66.0 | 56.5, 76.6 |

| Widowed/separated/divorced/single, never married | 52.6 | 32,519.7 | 683 | 210.0 | 98.2 | 89.3, 107.7 |

| Misreporting status | ||||||

| Underreporter | 34.4 | 21,804.4 | 311 | 142.6 | 91.4 | 80.9, 103.0 |

| Plausible reporter | 56.5 | 35,719.3 | 523 | 146.4 | 80.5 | 73.3, 88.3 |

| Overreporter | 9.1 | 5,815.2 | 82 | 141.0 | 83.4 | 65.4, 104.8 |

| Immigration status | ||||||

| Canadian born | 85.7 | 54,301.2 | 786 | 144.8 | 90.6 | 84.1, 97.6 |

| Immigrant | 14.3 | 9,037.7 | 130 | 143.8 | 53.0 | 43.3, 64.3 |

| Neighborhood deprivation indexb | ||||||

| Low | 11.6 | 7,360.3 | 95 | 129.1 | 73.3 | 58.6, 90.6 |

| Moderate | 68.1 | 43,206.1 | 604 | 139.8 | 82.5 | 75.5, 89.9 |

| High | 20.3 | 12,772.6 | 217 | 169.9 | 97.1 | 83.7, 112.1 |

| Self-perceived health | ||||||

| Poor | 4.2 | 2,380.8 | 97 | 407.4 | 200.3 | 155.5, 254.0 |

| Fair | 13.1 | 7,753.9 | 262 | 337.9 | 150.5 | 129.2, 174.2 |

| Good | 31.6 | 19,970.5 | 297 | 148.7 | 80.3 | 70.1, 91.6 |

| Very good | 34.7 | 2,2403.8 | 209 | 93.3 | 61.3 | 53.0, 70.5 |

| Excellent | 16.6 | 10,829.8 | 51 | 47.1 | 42.9 | 31.6, 57.0 |

| Self-perceived stress | ||||||

| Not at all stressful | 12.6 | 7,705.5 | 202 | 262.2 | 83.9 | 65.5, 106.0 |

| Not very stressful | 25.7 | 16,056.6 | 295 | 183.7 | 77.2 | 67.9, 87.5 |

| A bit stressful | 39.8 | 25,462.3 | 298 | 117.0 | 87.9 | 77.7, 99.0 |

| Quite a bit stressful | 18.2 | 11,739.7 | 96 | 81.8 | 90.4 | 72.1, 111.9 |

| Extremely stressful | 3.7 | 2,374.8 | 25 | 105.3 | 133.4 | 85.1, 199.2 |

| Sense of belonging to local community | ||||||

| Very strong | 25.3 | 15,883.1 | 281 | 176.9 | 73.9 | 64.6, 84.1 |

| Somewhat strong | 40.9 | 26,118.4 | 328 | 125.6 | 82.7 | 73.4, 92.8 |

| Somewhat weak | 22.2 | 14,099.7 | 181 | 128.4 | 88.5 | 75.6, 103.0 |

| Very weak | 11.6 | 7,237.7 | 126 | 174.1 | 120.1 | 98.6, 145.0 |

| Household food security status | ||||||

| Food secure | 91.9 | 58,030.8 | 885 | 152.5 | 82.8 | 77.0, 88.8 |

| Food insecure without hunger | 4.8 | 3,159.6 | 17 | 53.8 | 75.5 | 42.4, 124.3 |

| Food insecure with moderate/severe hunger | 3.1 | 2,022.5 | 14 | 69.2 | 137.5 | 37.2, 353.2 |

| Not stated | 0.2 | 126.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

a Body mass index calculated as weight (kg)/height (m)2.

b An area-based deprivation index was used that categorizes dissemination areas (smallest geostatistical units of Canadian census) into 2 sets of quintile groups: one for the social components of deprivation (% of people living alone, % of people divorced/separated, and % of single-parent families) and one for the material components (% without high school graduation, employment ratio, and the average income). Quintile 1 in each group represents the 20% least deprived while quintile 5 represents the 20% most deprived; when cross-tabulated, these quintiles create 25 distinct cells. We defined “low neighborhood deprivation” as dissemination areas with social and material combinations in quintiles 1 and 2 (4 cells) and “high neighborhood deprivation” as dissemination areas with social and material combinations in quintiles 4 and 5 (4 cells). The remaining dissemination areas (17 cells) were classified as having “moderate neighborhood deprivation” (57, 58).

Baseline Characteristics and Crude Mortality Rates per 10,000 Person-Years (Unweighted) Among Women (n = 8,857), Canadian Adults in Canadian Community Health Survey–Nutrition Linked to Canadian Vital Statistics Death Database, 2004/2005 to 2011

| Variable . | Frequency, % . | Person-Years . | No. of Deaths . | Crude Mortality Rate, Per 10,000 Person-Years . | Age-Standardized Rate . | 95% CI . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline age categories, years | 100 | 63,338.9 | 916 | 144.6 | 84.2 | 78.5, 90.2 |

| <45 | 33.3 | 22,087.6 | 16 | 7.2 | ||

| 45–80 | 57.6 | 36,569.5 | 520 | 142.2 | ||

| ≥80 | 9.1 | 4,681.8 | 380 | 811.7 | ||

| Age categories, 10-year intervals | ||||||

| <30 | 15.6 | 10,341.3 | 5 | 4.8 | ||

| 30–39 | 11.1 | 7,380.9 | 5 | 6.8 | ||

| 40–49 | 15.1 | 9,994.0 | 19 | 19.0 | ||

| 50–59 | 17.4 | 11,333.6 | 61 | 53.8 | ||

| 60–69 | 14.0 | 8,924.1 | 115 | 128.9 | ||

| 70–79 | 16.2 | 9,776.1 | 288 | 294.6 | ||

| 80–89 | 9.6 | 5,141.4 | 361 | 702.1 | ||

| ≥90 | 1.1 | 447.5 | 62 | 1,385.5 | ||

| Dietary reference intake age groups, years | ||||||

| <31 | 16.9 | 11,196.7 | 6 | 5.4 | ||

| 31–50 | 26.6 | 17,651.8 | 25 | 14.2 | ||

| 51–70 | 31.0 | 19,965.7 | 187 | 93.7 | ||

| ≥71 | 25.5 | 14,524.8 | 698 | 480.6 | ||

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Daily/occasional smoker with ≥20 but >90 cigarettes/day | 6.0 | 3,822.6 | 55 | 143.9 | 351.7 | 80.1, 982.6 |

| Daily/occasional smoker with <20 cigarettes/day | 17.3 | 11,098.0 | 110 | 99.1 | 121.7 | 99.4, 147.5 |

| Former daily/occasional smoker and those who smoked a total of ≥100 cigarettes in lifetime | 27.5 | 17,315.7 | 270 | 155.9 | 81.4 | 71.4, 92.4 |

| Never smoked | 49.2 | 31,102.5 | 481 | 154.7 | 70.1 | 63.2, 77.7 |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||||

| None | 8.6 | 16,275.6 | 441 | 271.0 | 103.0 | 90.7, 116.5 |

| Less than 1–3 times per month | 26.8 | 27,776.6 | 308 | 110.9 | 77.9 | 68.9, 87.7 |

| 1–3 times per week | 43.3 | 13,867.5 | 85 | 61.3 | 67.9 | 51.1, 88.4 |

| 4–7 times a week or being binge drinker: drank >2 times per week with the frequency of ≥5 drinks being 1 or more times per week | 21.3 | 5,419.2 | 82 | 151.3 | 81.1 | 63.0, 102.7 |

| Physical activity, metabolic equivalents/day | ||||||

| ≥3.0 | 15.8 | 10,232.7 | 63 | 61.6 | 62.6 | 45.6, 83.8 |

| 1.5–3.0 | 23.7 | 15,284.8 | 123 | 80.5 | 64.3 | 52.0, 78.7 |

| <1.5 | 60.6 | 37,821.5 | 730 | 193.0 | 95.2 | 87.7, 103.1 |

| Body mass indexa | ||||||

| <18.5 | 2.2 | 1,292.8 | 37 | 286.2 | 167.7 | 105.0, 254.2 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 36.7 | 23,134.6 | 349 | 150.9 | 88.4 | 78.6, 99.1 |

| 25.0–29.9 | 32.2 | 20,405.3 | 286 | 140.2 | 73.0 | 64.1, 82.9 |

| ≥30.0 | 29.0 | 18,506.2 | 244 | 131.9 | 87.6 | 76.0, 100.5 |

| Respondent’s highest level of education | ||||||

| Less than secondary school graduation | 28.6 | 17,362.1 | 487 | 280.5 | 102.9 | 88.8, 118.5 |

| Secondary school graduation | 17.5 | 11,118.8 | 138 | 124.1 | 87.8 | 72.4, 105.5 |

| Some postsecondary education | 8.2 | 5,269.9 | 49 | 93.0 | 87.4 | 64.2, 116.4 |

| Postsecondary graduation | 45.7 | 29,588.1 | 242 | 81.8 | 73.6 | 64.4, 83.8 |

| Current diabetes | ||||||

| Yes | 8.0 | 4,675.1 | 171 | 365.8 | 154.7 | 115.2, 203.4 |

| No | 92.0 | 58,663.8 | 745 | 127.0 | 77.0 | 71.2, 83.1 |

| Current heart disease | ||||||

| Yes | 8.5 | 4,684.0 | 253 | 540.1 | 130.0 | 106.4, 157.4 |

| No | 91.5 | 58,654.9 | 663 | 113.0 | 75.6 | 69.6, 81.9 |

| Current cancer | ||||||

| Yes | 2.6 | 1,410.4 | 76 | 538.8 | 191.3 | 143.9, 249.3 |

| No | 97.4 | 61,928.5 | 840 | 135.6 | 80.5 | 74.8, 86.6 |

| Current hypertension | ||||||

| Yes | 25.6 | 15,435.3 | 454 | 294.1 | 92.8 | 81.0, 105.9 |

| No | 74.4 | 47,903.6 | 462 | 96.4 | 79.0 | 71.8, 86.7 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married/common-law | 47.5 | 30,819.2 | 233 | 75.6 | 66.0 | 56.5, 76.6 |

| Widowed/separated/divorced/single, never married | 52.6 | 32,519.7 | 683 | 210.0 | 98.2 | 89.3, 107.7 |

| Misreporting status | ||||||

| Underreporter | 34.4 | 21,804.4 | 311 | 142.6 | 91.4 | 80.9, 103.0 |

| Plausible reporter | 56.5 | 35,719.3 | 523 | 146.4 | 80.5 | 73.3, 88.3 |

| Overreporter | 9.1 | 5,815.2 | 82 | 141.0 | 83.4 | 65.4, 104.8 |

| Immigration status | ||||||

| Canadian born | 85.7 | 54,301.2 | 786 | 144.8 | 90.6 | 84.1, 97.6 |

| Immigrant | 14.3 | 9,037.7 | 130 | 143.8 | 53.0 | 43.3, 64.3 |

| Neighborhood deprivation indexb | ||||||

| Low | 11.6 | 7,360.3 | 95 | 129.1 | 73.3 | 58.6, 90.6 |

| Moderate | 68.1 | 43,206.1 | 604 | 139.8 | 82.5 | 75.5, 89.9 |

| High | 20.3 | 12,772.6 | 217 | 169.9 | 97.1 | 83.7, 112.1 |

| Self-perceived health | ||||||

| Poor | 4.2 | 2,380.8 | 97 | 407.4 | 200.3 | 155.5, 254.0 |

| Fair | 13.1 | 7,753.9 | 262 | 337.9 | 150.5 | 129.2, 174.2 |

| Good | 31.6 | 19,970.5 | 297 | 148.7 | 80.3 | 70.1, 91.6 |

| Very good | 34.7 | 2,2403.8 | 209 | 93.3 | 61.3 | 53.0, 70.5 |

| Excellent | 16.6 | 10,829.8 | 51 | 47.1 | 42.9 | 31.6, 57.0 |

| Self-perceived stress | ||||||

| Not at all stressful | 12.6 | 7,705.5 | 202 | 262.2 | 83.9 | 65.5, 106.0 |

| Not very stressful | 25.7 | 16,056.6 | 295 | 183.7 | 77.2 | 67.9, 87.5 |

| A bit stressful | 39.8 | 25,462.3 | 298 | 117.0 | 87.9 | 77.7, 99.0 |

| Quite a bit stressful | 18.2 | 11,739.7 | 96 | 81.8 | 90.4 | 72.1, 111.9 |

| Extremely stressful | 3.7 | 2,374.8 | 25 | 105.3 | 133.4 | 85.1, 199.2 |

| Sense of belonging to local community | ||||||

| Very strong | 25.3 | 15,883.1 | 281 | 176.9 | 73.9 | 64.6, 84.1 |

| Somewhat strong | 40.9 | 26,118.4 | 328 | 125.6 | 82.7 | 73.4, 92.8 |

| Somewhat weak | 22.2 | 14,099.7 | 181 | 128.4 | 88.5 | 75.6, 103.0 |

| Very weak | 11.6 | 7,237.7 | 126 | 174.1 | 120.1 | 98.6, 145.0 |

| Household food security status | ||||||

| Food secure | 91.9 | 58,030.8 | 885 | 152.5 | 82.8 | 77.0, 88.8 |

| Food insecure without hunger | 4.8 | 3,159.6 | 17 | 53.8 | 75.5 | 42.4, 124.3 |

| Food insecure with moderate/severe hunger | 3.1 | 2,022.5 | 14 | 69.2 | 137.5 | 37.2, 353.2 |

| Not stated | 0.2 | 126.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Variable . | Frequency, % . | Person-Years . | No. of Deaths . | Crude Mortality Rate, Per 10,000 Person-Years . | Age-Standardized Rate . | 95% CI . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline age categories, years | 100 | 63,338.9 | 916 | 144.6 | 84.2 | 78.5, 90.2 |

| <45 | 33.3 | 22,087.6 | 16 | 7.2 | ||

| 45–80 | 57.6 | 36,569.5 | 520 | 142.2 | ||

| ≥80 | 9.1 | 4,681.8 | 380 | 811.7 | ||

| Age categories, 10-year intervals | ||||||

| <30 | 15.6 | 10,341.3 | 5 | 4.8 | ||

| 30–39 | 11.1 | 7,380.9 | 5 | 6.8 | ||

| 40–49 | 15.1 | 9,994.0 | 19 | 19.0 | ||

| 50–59 | 17.4 | 11,333.6 | 61 | 53.8 | ||

| 60–69 | 14.0 | 8,924.1 | 115 | 128.9 | ||

| 70–79 | 16.2 | 9,776.1 | 288 | 294.6 | ||

| 80–89 | 9.6 | 5,141.4 | 361 | 702.1 | ||

| ≥90 | 1.1 | 447.5 | 62 | 1,385.5 | ||

| Dietary reference intake age groups, years | ||||||

| <31 | 16.9 | 11,196.7 | 6 | 5.4 | ||

| 31–50 | 26.6 | 17,651.8 | 25 | 14.2 | ||

| 51–70 | 31.0 | 19,965.7 | 187 | 93.7 | ||

| ≥71 | 25.5 | 14,524.8 | 698 | 480.6 | ||

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Daily/occasional smoker with ≥20 but >90 cigarettes/day | 6.0 | 3,822.6 | 55 | 143.9 | 351.7 | 80.1, 982.6 |

| Daily/occasional smoker with <20 cigarettes/day | 17.3 | 11,098.0 | 110 | 99.1 | 121.7 | 99.4, 147.5 |

| Former daily/occasional smoker and those who smoked a total of ≥100 cigarettes in lifetime | 27.5 | 17,315.7 | 270 | 155.9 | 81.4 | 71.4, 92.4 |

| Never smoked | 49.2 | 31,102.5 | 481 | 154.7 | 70.1 | 63.2, 77.7 |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||||

| None | 8.6 | 16,275.6 | 441 | 271.0 | 103.0 | 90.7, 116.5 |

| Less than 1–3 times per month | 26.8 | 27,776.6 | 308 | 110.9 | 77.9 | 68.9, 87.7 |

| 1–3 times per week | 43.3 | 13,867.5 | 85 | 61.3 | 67.9 | 51.1, 88.4 |

| 4–7 times a week or being binge drinker: drank >2 times per week with the frequency of ≥5 drinks being 1 or more times per week | 21.3 | 5,419.2 | 82 | 151.3 | 81.1 | 63.0, 102.7 |

| Physical activity, metabolic equivalents/day | ||||||

| ≥3.0 | 15.8 | 10,232.7 | 63 | 61.6 | 62.6 | 45.6, 83.8 |

| 1.5–3.0 | 23.7 | 15,284.8 | 123 | 80.5 | 64.3 | 52.0, 78.7 |

| <1.5 | 60.6 | 37,821.5 | 730 | 193.0 | 95.2 | 87.7, 103.1 |

| Body mass indexa | ||||||

| <18.5 | 2.2 | 1,292.8 | 37 | 286.2 | 167.7 | 105.0, 254.2 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 36.7 | 23,134.6 | 349 | 150.9 | 88.4 | 78.6, 99.1 |

| 25.0–29.9 | 32.2 | 20,405.3 | 286 | 140.2 | 73.0 | 64.1, 82.9 |

| ≥30.0 | 29.0 | 18,506.2 | 244 | 131.9 | 87.6 | 76.0, 100.5 |

| Respondent’s highest level of education | ||||||

| Less than secondary school graduation | 28.6 | 17,362.1 | 487 | 280.5 | 102.9 | 88.8, 118.5 |

| Secondary school graduation | 17.5 | 11,118.8 | 138 | 124.1 | 87.8 | 72.4, 105.5 |

| Some postsecondary education | 8.2 | 5,269.9 | 49 | 93.0 | 87.4 | 64.2, 116.4 |

| Postsecondary graduation | 45.7 | 29,588.1 | 242 | 81.8 | 73.6 | 64.4, 83.8 |

| Current diabetes | ||||||

| Yes | 8.0 | 4,675.1 | 171 | 365.8 | 154.7 | 115.2, 203.4 |

| No | 92.0 | 58,663.8 | 745 | 127.0 | 77.0 | 71.2, 83.1 |

| Current heart disease | ||||||

| Yes | 8.5 | 4,684.0 | 253 | 540.1 | 130.0 | 106.4, 157.4 |

| No | 91.5 | 58,654.9 | 663 | 113.0 | 75.6 | 69.6, 81.9 |

| Current cancer | ||||||

| Yes | 2.6 | 1,410.4 | 76 | 538.8 | 191.3 | 143.9, 249.3 |

| No | 97.4 | 61,928.5 | 840 | 135.6 | 80.5 | 74.8, 86.6 |

| Current hypertension | ||||||

| Yes | 25.6 | 15,435.3 | 454 | 294.1 | 92.8 | 81.0, 105.9 |

| No | 74.4 | 47,903.6 | 462 | 96.4 | 79.0 | 71.8, 86.7 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married/common-law | 47.5 | 30,819.2 | 233 | 75.6 | 66.0 | 56.5, 76.6 |

| Widowed/separated/divorced/single, never married | 52.6 | 32,519.7 | 683 | 210.0 | 98.2 | 89.3, 107.7 |

| Misreporting status | ||||||

| Underreporter | 34.4 | 21,804.4 | 311 | 142.6 | 91.4 | 80.9, 103.0 |

| Plausible reporter | 56.5 | 35,719.3 | 523 | 146.4 | 80.5 | 73.3, 88.3 |

| Overreporter | 9.1 | 5,815.2 | 82 | 141.0 | 83.4 | 65.4, 104.8 |

| Immigration status | ||||||

| Canadian born | 85.7 | 54,301.2 | 786 | 144.8 | 90.6 | 84.1, 97.6 |

| Immigrant | 14.3 | 9,037.7 | 130 | 143.8 | 53.0 | 43.3, 64.3 |

| Neighborhood deprivation indexb | ||||||

| Low | 11.6 | 7,360.3 | 95 | 129.1 | 73.3 | 58.6, 90.6 |

| Moderate | 68.1 | 43,206.1 | 604 | 139.8 | 82.5 | 75.5, 89.9 |

| High | 20.3 | 12,772.6 | 217 | 169.9 | 97.1 | 83.7, 112.1 |

| Self-perceived health | ||||||

| Poor | 4.2 | 2,380.8 | 97 | 407.4 | 200.3 | 155.5, 254.0 |

| Fair | 13.1 | 7,753.9 | 262 | 337.9 | 150.5 | 129.2, 174.2 |

| Good | 31.6 | 19,970.5 | 297 | 148.7 | 80.3 | 70.1, 91.6 |

| Very good | 34.7 | 2,2403.8 | 209 | 93.3 | 61.3 | 53.0, 70.5 |

| Excellent | 16.6 | 10,829.8 | 51 | 47.1 | 42.9 | 31.6, 57.0 |

| Self-perceived stress | ||||||

| Not at all stressful | 12.6 | 7,705.5 | 202 | 262.2 | 83.9 | 65.5, 106.0 |

| Not very stressful | 25.7 | 16,056.6 | 295 | 183.7 | 77.2 | 67.9, 87.5 |

| A bit stressful | 39.8 | 25,462.3 | 298 | 117.0 | 87.9 | 77.7, 99.0 |

| Quite a bit stressful | 18.2 | 11,739.7 | 96 | 81.8 | 90.4 | 72.1, 111.9 |

| Extremely stressful | 3.7 | 2,374.8 | 25 | 105.3 | 133.4 | 85.1, 199.2 |

| Sense of belonging to local community | ||||||

| Very strong | 25.3 | 15,883.1 | 281 | 176.9 | 73.9 | 64.6, 84.1 |

| Somewhat strong | 40.9 | 26,118.4 | 328 | 125.6 | 82.7 | 73.4, 92.8 |

| Somewhat weak | 22.2 | 14,099.7 | 181 | 128.4 | 88.5 | 75.6, 103.0 |

| Very weak | 11.6 | 7,237.7 | 126 | 174.1 | 120.1 | 98.6, 145.0 |

| Household food security status | ||||||

| Food secure | 91.9 | 58,030.8 | 885 | 152.5 | 82.8 | 77.0, 88.8 |

| Food insecure without hunger | 4.8 | 3,159.6 | 17 | 53.8 | 75.5 | 42.4, 124.3 |

| Food insecure with moderate/severe hunger | 3.1 | 2,022.5 | 14 | 69.2 | 137.5 | 37.2, 353.2 |

| Not stated | 0.2 | 126.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

a Body mass index calculated as weight (kg)/height (m)2.

b An area-based deprivation index was used that categorizes dissemination areas (smallest geostatistical units of Canadian census) into 2 sets of quintile groups: one for the social components of deprivation (% of people living alone, % of people divorced/separated, and % of single-parent families) and one for the material components (% without high school graduation, employment ratio, and the average income). Quintile 1 in each group represents the 20% least deprived while quintile 5 represents the 20% most deprived; when cross-tabulated, these quintiles create 25 distinct cells. We defined “low neighborhood deprivation” as dissemination areas with social and material combinations in quintiles 1 and 2 (4 cells) and “high neighborhood deprivation” as dissemination areas with social and material combinations in quintiles 4 and 5 (4 cells). The remaining dissemination areas (17 cells) were classified as having “moderate neighborhood deprivation” (57, 58).

Weighted and Multivariable-Adjusted Hazard Ratios for All-Cause Mortality According to 1-Unit Increase in Usual Intake Score of 5 Dietary Quality Index Scores Reported at Midpoint of Quintiles, Canadian Adults in Canadian Community Health Survey–Nutrition Linked to Canadian Vital Statistics Death Database, 2004/2005 to 2011

| . | . | . | Model 1c,d . | Model 2c . | Model 3 (Main Model)c,e . | Model 4c,f . | Model 5g,h . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quintile . | Median Scorea . | Median Scoreb . | HRi . | 95% CI . | HRi . | 95% CI . | HRi . | 95% CI . | HRi . | 95% CI . | HRi . | 95% CI . |

| Dietary Guideline for Americans Adherence Index 2015j | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 6.64 | 6.42 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| 2 | 7.48 | 7.23 | 0.78 | 0.70, 0.86 | 0.81 | 0.71, 0.93 | 0.81 | 0.71, 0.93 | 0.82 | 0.71, 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.82, 1.00 |

| 3 | 8.06 | 7.82 | 0.65 | 0.55, 0.78 | 0.71 | 0.57, 0.89 | 0.7 | 0.56, 0.88 | 0.71 | 0.56, 0.88 | 0.85 | 0.71, 1.01 |

| 4 | 8.57 | 8.36 | 0.56 | 0.43, 0.71 | 0.63 | 0.46, 0.85 | 0.62 | 0.45, 0.84 | 0.62 | 0.46, 0.85 | 0.79 | 0.62, 1.01 |

| 5 | 9.32 | 9.14 | 0.44 | 0.31, 0.62 | 0.52 | 0.34, 0.79 | 0.51 | 0.33, 0.79 | 0.52 | 0.34, 0.79 | 0.72 | 0.51, 1.01 |

| Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension 2017k | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 36.96 | 36.26 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| 2 | 41.19 | 40.33 | 0.79 | 0.72, 0.87 | 0.83 | 0.74, 0.93 | 0.82 | 0.73, 0.92 | 0.82 | 0.72, 0.92 | 0.89 | 0.81, 0.97 |

| 3 | 44.56 | 43.50 | 0.66 | 0.56, 0.79 | 0.72 | 0.58, 0.88 | 0.7 | 0.57, 0.86 | 0.7 | 0.57, 0.87 | 0.81 | 0.68, 0.96 |

| 4 | 47.89 | 46.57 | 0.55 | 0.43, 0.71 | 0.62 | 0.46, 0.83 | 0.6 | 0.44, 0.81 | 0.6 | 0.44, 0.81 | 0.74 | 0.58, 0.94 |

| 5 | 52.04 | 50.84 | 0.43 | 0.30, 0.61 | 0.52 | 0.34, 0.77 | 0.49 | 0.32, 0.75 | 0.49 | 0.33, 0.75 | 0.65 | 0.47, 0.91 |

| Healthy Eating Index 2010j | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 49.87 | 48.83 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| 2 | 55.79 | 54.36 | 0.8 | 0.73, 0.88 | 0.83 | 0.74, 0.93 | 0.82 | 0.73, 0.93 | 0.83 | 0.73, 0.93 | 0.89 | 0.80, 0.99 |

| 3 | 59.69 | 58.08 | 0.68 | 0.58, 0.81 | 0.74 | 0.61, 0.89 | 0.72 | 0.59, 0.89 | 0.73 | 0.60, 0.89 | 0.82 | 0.70, 0.98 |

| 4 | 63.72 | 61.85 | 0.58 | 0.46, 0.74 | 0.65 | 0.49, 0.85 | 0.63 | 0.48, 0.84 | 0.64 | 0.48, 0.85 | 0.76 | 0.60, 0.97 |

| 5 | 68.68 | 66.66 | 0.47 | 0.34, 0.66 | 0.56 | 0.38, 0.80 | 0.54 | 0.37, 0.79 | 0.55 | 0.37, 0.80 | 0.69 | 0.50, 0.95 |

| Alternative Healthy Eating Index 2010j,l | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 30.28 | 28.00 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| 2 | 34.11 | 32.08 | 0.82 | 0.76, 0.89 | 0.86 | 0.79, 0.94 | 0.85 | 0.78, 0.93 | 0.85 | 0.77, 0.93 | 0.85 | 0.78, 0.93 |

| 3 | 36.88 | 34.93 | 0.71 | 0.62, 0.82 | 0.77 | 0.66, 0.90 | 0.76 | 0.65, 0.89 | 0.75 | 0.64, 0.88 | 0.76 | 0.66, 0.88 |

| 4 | 39.77 | 37.81 | 0.62 | 0.51, 0.75 | 0.69 | 0.55, 0.86 | 0.68 | 0.54, 0.84 | 0.66 | 0.53, 0.84 | 0.68 | 0.56, 0.83 |

| 5 | 43.89 | 42.13 | 0.49 | 0.37, 0.66 | 0.58 | 0.43, 0.80 | 0.57 | 0.41, 0.79 | 0.56 | 0.40, 0.78 | 0.57 | 0.43, 0.76 |

| Mediterranean Style Dietary Pattern Score 2009j,l | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 10.17 | 10.25 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| 2 | 11.99 | 12.09 | 0.88 | 0.81, 0.96 | 0.9 | 0.81, 1.00 | 0.9 | 0.80, 1.00 | 0.9 | 0.81, 1.02 | 0.93 | 0.86, 1.01 |

| 3 | 13.35 | 13.53 | 0.8 | 0.69, 0.92 | 0.83 | 0.68, 1.00 | 0.83 | 0.68, 1.00 | 0.83 | 0.68, 1.03 | 0.88 | 0.76, 1.01 |

| 4 | 14.64 | 14.91 | 0.72 | 0.58, 0.89 | 0.76 | 0.58, 1.00 | 0.77 | 0.58, 1.00 | 0.77 | 0.58, 1.04 | 0.83 | 0.68, 1.01 |

| 5 | 16.51 | 16.82 | 0.62 | 0.46, 0.85 | 0.68 | 0.47, 0.99 | 0.68 | 0.47, 1.00 | 0.7 | 0.46, 1.06 | 0.77 | 0.58, 1.02 |

| . | . | . | Model 1c,d . | Model 2c . | Model 3 (Main Model)c,e . | Model 4c,f . | Model 5g,h . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quintile . | Median Scorea . | Median Scoreb . | HRi . | 95% CI . | HRi . | 95% CI . | HRi . | 95% CI . | HRi . | 95% CI . | HRi . | 95% CI . |

| Dietary Guideline for Americans Adherence Index 2015j | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 6.64 | 6.42 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| 2 | 7.48 | 7.23 | 0.78 | 0.70, 0.86 | 0.81 | 0.71, 0.93 | 0.81 | 0.71, 0.93 | 0.82 | 0.71, 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.82, 1.00 |

| 3 | 8.06 | 7.82 | 0.65 | 0.55, 0.78 | 0.71 | 0.57, 0.89 | 0.7 | 0.56, 0.88 | 0.71 | 0.56, 0.88 | 0.85 | 0.71, 1.01 |

| 4 | 8.57 | 8.36 | 0.56 | 0.43, 0.71 | 0.63 | 0.46, 0.85 | 0.62 | 0.45, 0.84 | 0.62 | 0.46, 0.85 | 0.79 | 0.62, 1.01 |

| 5 | 9.32 | 9.14 | 0.44 | 0.31, 0.62 | 0.52 | 0.34, 0.79 | 0.51 | 0.33, 0.79 | 0.52 | 0.34, 0.79 | 0.72 | 0.51, 1.01 |

| Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension 2017k | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 36.96 | 36.26 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| 2 | 41.19 | 40.33 | 0.79 | 0.72, 0.87 | 0.83 | 0.74, 0.93 | 0.82 | 0.73, 0.92 | 0.82 | 0.72, 0.92 | 0.89 | 0.81, 0.97 |

| 3 | 44.56 | 43.50 | 0.66 | 0.56, 0.79 | 0.72 | 0.58, 0.88 | 0.7 | 0.57, 0.86 | 0.7 | 0.57, 0.87 | 0.81 | 0.68, 0.96 |

| 4 | 47.89 | 46.57 | 0.55 | 0.43, 0.71 | 0.62 | 0.46, 0.83 | 0.6 | 0.44, 0.81 | 0.6 | 0.44, 0.81 | 0.74 | 0.58, 0.94 |

| 5 | 52.04 | 50.84 | 0.43 | 0.30, 0.61 | 0.52 | 0.34, 0.77 | 0.49 | 0.32, 0.75 | 0.49 | 0.33, 0.75 | 0.65 | 0.47, 0.91 |

| Healthy Eating Index 2010j | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 49.87 | 48.83 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| 2 | 55.79 | 54.36 | 0.8 | 0.73, 0.88 | 0.83 | 0.74, 0.93 | 0.82 | 0.73, 0.93 | 0.83 | 0.73, 0.93 | 0.89 | 0.80, 0.99 |

| 3 | 59.69 | 58.08 | 0.68 | 0.58, 0.81 | 0.74 | 0.61, 0.89 | 0.72 | 0.59, 0.89 | 0.73 | 0.60, 0.89 | 0.82 | 0.70, 0.98 |

| 4 | 63.72 | 61.85 | 0.58 | 0.46, 0.74 | 0.65 | 0.49, 0.85 | 0.63 | 0.48, 0.84 | 0.64 | 0.48, 0.85 | 0.76 | 0.60, 0.97 |

| 5 | 68.68 | 66.66 | 0.47 | 0.34, 0.66 | 0.56 | 0.38, 0.80 | 0.54 | 0.37, 0.79 | 0.55 | 0.37, 0.80 | 0.69 | 0.50, 0.95 |

| Alternative Healthy Eating Index 2010j,l | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 30.28 | 28.00 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| 2 | 34.11 | 32.08 | 0.82 | 0.76, 0.89 | 0.86 | 0.79, 0.94 | 0.85 | 0.78, 0.93 | 0.85 | 0.77, 0.93 | 0.85 | 0.78, 0.93 |

| 3 | 36.88 | 34.93 | 0.71 | 0.62, 0.82 | 0.77 | 0.66, 0.90 | 0.76 | 0.65, 0.89 | 0.75 | 0.64, 0.88 | 0.76 | 0.66, 0.88 |

| 4 | 39.77 | 37.81 | 0.62 | 0.51, 0.75 | 0.69 | 0.55, 0.86 | 0.68 | 0.54, 0.84 | 0.66 | 0.53, 0.84 | 0.68 | 0.56, 0.83 |

| 5 | 43.89 | 42.13 | 0.49 | 0.37, 0.66 | 0.58 | 0.43, 0.80 | 0.57 | 0.41, 0.79 | 0.56 | 0.40, 0.78 | 0.57 | 0.43, 0.76 |

| Mediterranean Style Dietary Pattern Score 2009j,l | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 10.17 | 10.25 | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent | 1.00 | Referent |

| 2 | 11.99 | 12.09 | 0.88 | 0.81, 0.96 | 0.9 | 0.81, 1.00 | 0.9 | 0.80, 1.00 | 0.9 | 0.81, 1.02 | 0.93 | 0.86, 1.01 |

| 3 | 13.35 | 13.53 | 0.8 | 0.69, 0.92 | 0.83 | 0.68, 1.00 | 0.83 | 0.68, 1.00 | 0.83 | 0.68, 1.03 | 0.88 | 0.76, 1.01 |

| 4 | 14.64 | 14.91 | 0.72 | 0.58, 0.89 | 0.76 | 0.58, 1.00 | 0.77 | 0.58, 1.00 | 0.77 | 0.58, 1.04 | 0.83 | 0.68, 1.01 |

| 5 | 16.51 | 16.82 | 0.62 | 0.46, 0.85 | 0.68 | 0.47, 0.99 | 0.68 | 0.47, 1.00 | 0.7 | 0.46, 1.06 | 0.77 | 0.58, 1.02 |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

a Weighted and error-adjusted usual intake median of the dietary quality index score; corresponds to models 1–4 (45 ≤ age group ≤ 80 years) (midpoint of quintiles).

b Weighted and error-adjusted usual intake median of the dietary quality index score; corresponds to model 5 (≥20 years) (midpoint of quintiles).

c Weighted n = 11,313,844 (unweighted n = 9,174); weighted number of deaths: 900,182.7 (unweighted n = 1,070); weighted person-years = 81,754,462.1 (unweighted person-years = 65,175.1).

d Model 1 (45 ≤ age group≤80 years): adjusted for day of the week on which 24-hour dietary recall was collected (weekday/weekend (Friday–Sunday)), sequence of dietary recall (first or second), baseline age (continuous), and sex.

e Model 3 (45 ≤ age group≤80 years): model 2 covariates in addition to diagnosis of diabetes (yes/no), cancer (yes/no), or heart disease (yes/no) and body mass index (underweight; normal weight; overweight; obese).

f Model 4 (45 ≤ age group ≤ 80 years): model 3 covariates minus misreporting (underreporter, plausible reporter, and overreporter).

g Weighted n = 22,898,880 (unweighted n = 16,212); weighted number of deaths: 1,358,206 (unweighted n = 1,722); unweighted person-years = 115645.4.

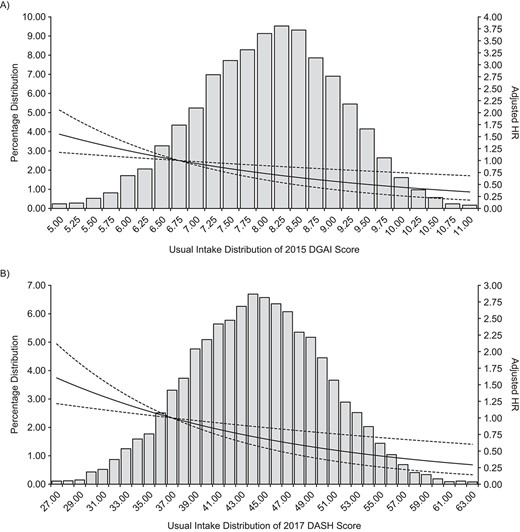

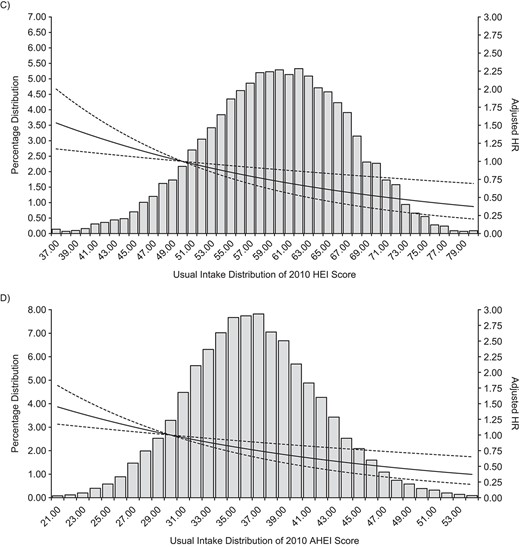

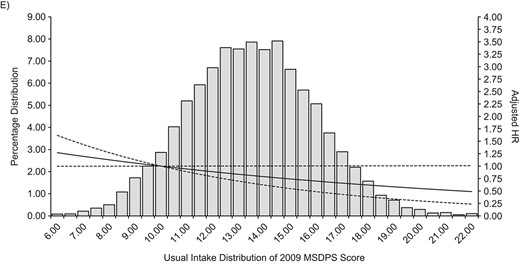

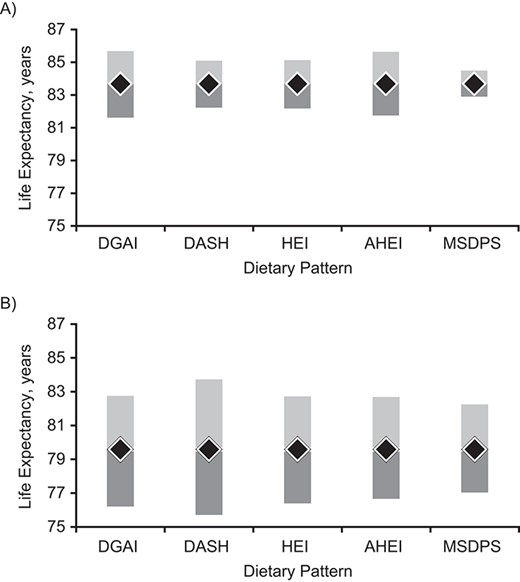

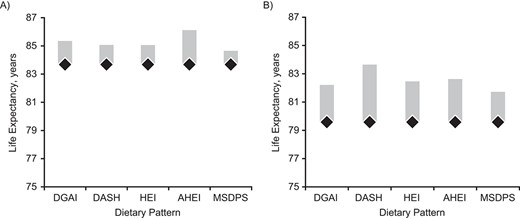

h Model 5 (20 ≤ age group): model 3 covariates with the full sample of ≥20 year olds.