-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

David D Celentano, Elizabeth Platz, Shruti H Mehta, The Centennial of the Department of Epidemiology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health: A Century of Epidemiologic Discovery and Education, American Journal of Epidemiology, Volume 188, Issue 12, December 2019, Pages 2043–2048, https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwz176

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The Department of Epidemiology at Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health was founded in 1919, with Wade Hampton Frost as inaugural chair. In our Centennial Year, we review how our research and educational programs have changed. Early years focused on doctoral education in epidemiology and some limited undergraduate training for practice. Foundational work on concepts and methods linked to the infectious diseases of the day made major contributions to study designs and analytical methodologies, largely still in use. With the epidemiologic transition from infectious to chronic disease, new methods were developed. The Department of Chronic Diseases merged with the Department of Epidemiology in 1970, under the leadership of Abraham Lilienfeld. Leon Gordis became chair in 1975, and multiple educational tracks were developed. Genetic epidemiology began in 1979, followed by advances in infectious disease epidemiology spurred by the human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome epidemic. Collaborations with the Department of Medicine led to development of the Welch Center for Prevention, Epidemiology, and Clinical Research in 1989. Between 1994 and 2008, the department experienced rapid growth in faculty and students. A new methods curriculum was instituted for upper-level epidemiologic training in 2006. Today’s research projects are increasingly collaborative, taking advantage of new technologies and methods of data collection, responding to “big data” analysis challenges. In our second century, the department continues to address issues of disease etiology and epidemiologic practice.

When the International Health Board of the Rockefeller Foundation selected the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health as the first school of its type in the United States in 1916, William Henry Welch was appointed as the inaugural dean. The Department of Epidemiology was one of the foundational departments when students matriculated in 1919. The initial faculty appointments in the School were in the disciplines of physiological hygiene (William H. Howell), bacteriology and sanitary engineering (William W. Ford), chemical hygiene (Elmer Verner McCollum), biometry and vital statistics (Raymond Pearl and Lowell Reed), tropical medicine (Robert Hegner, William Cort, and Francis Root) and epidemiology (Wade Hampton Frost) (1). This storied cohort of faculty served as the brain trust for Welch’s “institute of hygiene.”

In 1918, following his release from a tuberculosis sanitorium, Frost analyzed the 1918 influenza pandemic using both field methods and careful statistical analysis (2). Frost and Edgar Sydenstricker, a statistician and close collaborator, published data on the global spread of influenza in 1919 (3). As his biographer Thomas M. Daniel stated in his 2004 history, Wade Hampton Frost, Pioneer Epidemiologist 1880–1938: Up to the Mountain, pneumonia and influenza mortality in Massachusetts between 1887 and 1916 were strongly correlated with cyclical seasonal peaks (4). Frost’s contributions to the developing scientific discipline of epidemiology were manifold: mathematical models of epidemic curves of infectious diseases (with Lowell Reed), the study of tuberculosis epidemiology, and using life tables incorporating age stratification to estimate secondary attack rates, among other firsts.

Frost created the first syllabus in epidemiology at Johns Hopkins. Appendix 1 is Frost’s syllabus as printed in the Johns Hopkins University Circular of Summer Courses 1920. This comprehensive introduction to the epidemiologic methods of data collection, collation, analysis, and interpretation required 18 hours of student participation per week (roughly equivalent to a 6-credit semester-long course). Using contemporary public health examples, which of course were predominately infectious diseases at that time, the methods of investigation were presented in lectures and illustrated through the analysis of real-time epidemiologic data from Baltimore. This was supplemented by field work leading to a culminating experience, akin to today’s “integrative learning experience”: “a brief thesis on an assigned subject in epidemiology.”

EPIDEMIOLOGIC DISCOVERY

Cataloging the past achievements of a diverse and growing faculty of the Department of Epidemiology is challenging. However, reviewing these accomplishments provides a brief snapshot into the available methods, existing tools, and the leading public health problems of the day. What is most striking perhaps is how some of the early pioneering work continues to influence the way we approach and address contemporary public health challenges. In the early days, Frost developed the methods used in the analysis of birth cohorts, Kenneth Maxcy investigated rickettsial infections in the South, and Philip Sartwell characterized the log normal distribution of incubation periods. It was also during this period that Alexander Langmuir departed Johns Hopkins to form the Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS) at the Centers for Disease Control. Faculty from the department—Lilienfeld, John Hume (who would later become dean) and Sartwell—trained the first class of Epidemic Intelligence Service officers in the essentials of “shoe-leather epidemiology” (1), a term attributed to Frost.

In the second half of the 20th Century, Abraham Lilienfeld applied epidemiologic methods developed for the study of infectious diseases to chronic medical conditions such as cancer and cardiovascular diseases. George W. Comstock pioneered the use of the community randomized clinical trial to demonstrate the efficacy of isoniazid for the control of tuberculosis. Additionally, with Lilienfeld, Comstock demonstrated the value of a population-based serum bank, which continues to be the basis for numerous case-cohort and nested case-control studies within defined cohorts conducted today. With the emergence of the human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) epidemic, the department returned to infectious diseases and became increasingly engaged in international research. Jon Samet led school-wide investigations of environmental exposures to air pollution, radon, and secondhand smoke. Much of the department’s research is conducted in 14 affiliated centers ( Appendix 2).

PEDAGOGY IN EPIDEMIOLOGY OVER THE CENTURY

Frost’s “collateral readings” for his 1920 syllabus for Epidemiology consisted of recent publications and working papers—there was insufficient depth of material in the literature on the methods of epidemiology to be used as a textbook. The first text by a Johns Hopkins faculty member was not published until 1976: Lilienfeld’s Foundations of Epidemiology (5). It was Leon Gordis’s Epidemiology (6), published 20 years later, that became the internationally renowned text that has been most widely adopted in the teaching of introductory epidemiology. It is now published by Elsevier as Gordis Epidemiology, 6th Edition, by Celentano and Szklo (7).

A signature achievement of Samet’s tenure as chair (1994–2008) was a complete revamp and refresh of the epidemiologic methods curriculum, with a focus on teaching advanced epidemiologic methods. The courses that were taught at the turn of the millennium had changed little since the 1970s and 1980s. Samet led a faculty group to rethink the teaching of epidemiology over a 3-year period, grounding the curriculum in a philosophical foundation to guide our approach, and updating the design and analytical approaches underlying contemporary epidemiologic research. This update, consisting of a series of 4 integrated courses, was completed in 2006 and is continually revised as new instructors take leadership roles in teaching. The teaching of epidemiology in the school is now divided into several “streams”—for those reading the epidemiologic literature, for those doing epidemiologic practice in the field, and for those conducting epidemiologic research using advanced epidemiologic methods.

Today, the department admits students to the PhD, MHS, and ScM degrees. Teaching is done through 68 formal face-to-face courses, 30 online courses for full-time and distance education students, a vibrant Graduate Summer Institute of Epidemiology and Biostatistics (now in its 37th year under the direction of Moyses Szklo), and short-term concentrated courses offered annually through formal Institutes in Beijing, India, and Spain.

EVOLUTION OF THE DEPARTMENT OF EPIDEMIOLOGY

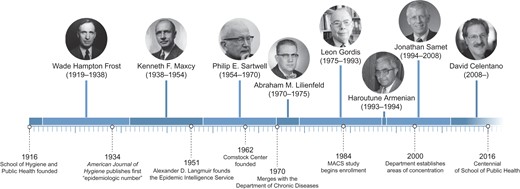

Figure 1 shows the evolution and growth of the department from its inception in 1919 to its status today (8). The department began with Frost as the sole professor in the department, soon followed by 2 associate professors and 2 instructors, assisted by 2 statistical clerks and a secretary/stenographer. The faculty were housed in 3 rooms in McCoy Hall on Broadway in space provided by the School of Medicine, and they taught 1 introductory course ( Appendix 1) to the small number of DrPH and ScD students who matriculated that first year (physicians were admitted to the DrPH, which could be completed in 2 years, and public health specialists were admitted to the ScD program, to be completed in 3 years with a dissertation) (1). Miriam Brailey, who instituted the study of disparities in tuberculosis care in Baltimore, was the first woman hired as a professor in the department, in 1932; she remained active until 1959 (1).

History of the Department of Epidemiology of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Reproduced from Celentano (Am J Epidemiol. 2016;183(5):355–361) (8) by permission of Oxford University Press. MACS, Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study.

Maxcy became chair when Frost died in 1938 and held the position until 1954. Like Frost, he was a physician, but he also received a DrPH in epidemiology from Johns Hopkins in 1921, after which he served in the US Public Health Service for 8 years. As his biographers Wood and Wood wrote, “At the annual meeting of the American Public Health Association in 1952, the William T. Sedgwick Memorial Medal was awarded to Dr. Maxcy. In making the presentation, Dr. Karl F. Meyer said in part: ‘Under his guidance, teaching and research in epidemiology has, through the years, undergone a subtle transition. From a descriptive science overshadowed by an anthropocentric point of view it has become a biologic science . . . ’” (9, p. 164). The department was growing at this time, in part due the emergence of polio and the advent of vaccine development. Maxcy brought on 3 faculty—David Bodian, Howard Howe, and Isabelle Morgan—who did groundbreaking work on the inactivated polio vaccine. One recruit during Maxcy’s tenure was Langmuir, of Epidemic Intelligence Service fame at the Centers for Disease Control. The Epidemic Intelligence Service was originally started to protect the American public from biological warfare and manmade epidemics; this is remarkably similar to the contemporary concerns with “health security.”

Sartwell chaired the department from 1954 to 1970, a time of transition from infectious diseases to chronic diseases making the majority contribution to the morbidity and mortality of Americans. His most notable contributions were in the fields of thrombotic complications of oral contraceptives in the 1950s, characterizing the distributions of incubation periods of infectious diseases in the 1960s, addressing occupational exposure to medical radiation, and in the design of population-based field studies. Sartwell hired Genevieve Matanoski, an environmental epidemiologist, in 1958; she completed her DrPH in the department in 1964 and remains on our faculty today. The most well-known faculty hire during Sartwell’s tenure was Comstock, who joined the faculty in 1961 to reinvigorate the Public Health Training Center in Hagerstown. As one of the 2 original (1921) field sites for epidemiologic training jointly developed by the school and the Maryland State Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, it had fallen on tough times. Comstock renewed a presence in Hagerstown with a small group of health workers and clerks to use the center as a base of operations for community-based research to support both epidemiology and public health practice through a close relationship with the Washington County Health Department; this vibrant collaboration continues today. A large body of epidemiologic evidence has grown from the original private county census Comstock conducted in 1963, and the first serum bank specimens were collected in 1974 (CLUE I study). This repository has been used to address epidemiologic hypotheses decades later in ways that were not previously possible. The center, renamed the George W. Comstock Center for Public Health Research and Prevention in his honor, is home to a large portfolio of NIH-supported research studies on disease prevention, under the directorship of Josef Coresh. The focus today is on cardiovascular disease, cancer, stroke, and dementia.

Lilienfeld was Chair of the Department of Chronic Disease from 1958 to 1970, and this department merged with the Department of Epidemiology in 1970 (10). As Karen Kruse Thomas writes, “Lilienfeld’s approach to chronic disease was guided by two disciplines that rose to broad influence in the 1950s: social sciences and medical genetics” (11, p. 322). Demonstrating his prescient awareness of the social determinants of disease, when Lilienfeld started the Department of Chronic Disease, his first faculty hires were a sociologist, an anthropologist, and a political scientist. He inaugurated an interdisciplinary course in the school, Human Genetics, with Bentley Glass (from the Department of Biology), Barton Childs (from the Department of Pediatrics), and Victor McKusick (from the Division of Medical Genetics in the School of Medicine). Cancer research became a cornerstone of the department’s research agenda, which then expanded to many other areas (11). As his New York Times obituary stated on August 8, 1984, “Dr. Lilienfeld was instrumental in expanding epidemiology from a discipline focused on infectious diseases to one embracing chronic diseases including cancer, cerebral palsy, epilepsy, heart disease and stroke” (12, p. D21). Lilienfeld suffered a myocardial infarction in 1974 while lecturing in his introductory course, “Principles of Epidemiology,” and in his recovery, the chair passed to Gordis.

Gordis, a pediatrician and DrPH-trained epidemiologist (from the department), served as chair from 1975 to 1993. During that time, many faculty members were recruited, and the department became specialized, with the formation of educational tracks in 1979. The initial tracks included Chronic Disease and Clinical Epidemiology, Infectious Diseases Epidemiology, Genetic Epidemiology, and Occupational and Environmental Epidemiology. By 1986, Chronic Diseases and Clinical Epidemiology split into 2 separate tracks. Gordis was perhaps best known for his teaching acumen. During his career, he taught thousands of public health and medical students their introductory course in epidemiology. His textbook, Epidemiology (6), became the go-to source for beginning students. Gordis had a knack for making somewhat complex epidemiologic principles seem simple and accessible, and he presented them in the style of a detective story. Students loved his course, his humor, and his teaching style; he won the student teaching award in the school (the Golden Apple) each time he was eligible. He also gained significant notoriety for his role in the 1990s on a controversial expert panel that he chaired for the National Institutes of Health that advised against routine mammography for the early detection of breast cancer for women under the age of 50 years. That recommendation did not go over very well with radiologists and cancer specialists.

During the Gordis years, Bernice Cohen established the first formal academic training program in genetic epidemiology in the department in 1979. Originally trained in genetics at the Arts and Sciences campus of Johns Hopkins, she had the vision to bring the disciplines of genetics and epidemiology together (11). Cohen was a driving force in establishing this new scientific discipline and helped define its importance in public health. Today, many epidemiologic studies consider the relative contribution of genetics and epigenetics as well as traditional risk-factor assessment in epidemiologic investigations.

It was also during Gordis’s tenure that the HIV epidemic began in earnest. Gordis recruited B. Frank Polk in 1982 to reenergize infectious-diseases epidemiology teaching and research. Polk had been investigating obstetrical infections and cardiovascular disease at the Harvard Channing Laboratory in Boston. Shortly after his arrival, HIV emerged as a major issue in Baltimore (and throughout the world), and Polk galvanized the efforts of the Johns Hopkins community in response to this challenging new viral infection with John Bartlett, the Director of the Division of Infectious Diseases in the School of Medicine. He started the first HIV cohort studies in men who have sex with men (the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study, in 1984) and people who inject drugs (AIDS Linked to the IntraVenous Experience, in 1987), both of which remain active today. He also was an early investigator in sub-Saharan Africa, starting the first cohort study of maternal-to-child HIV transmission in Malawi. In 2019, Johns Hopkins is the nation’s leading recipient of NIH research funds to study HIV/AIDS, a legacy of Frank Polk’s passion, commitment, and leadership.

In 1989, Gordis and Paul Whelton, a professor in medicine, founded the Welch Center for Prevention, Epidemiology, and Clinical Research. This collaboration between the departments of epidemiology and medicine has been unusually successful in building bridges and collaborative research between the 2 schools.

Gordis stepped down as chair in 1993. Haroutune Armenian, himself a DrPH graduate of the department and Gordis’s deputy chair, served as interim chair for a year, until Samet was recruited from New Mexico in 1994. Under Samet, the faculty numbers expanded, and student applications and admissions increased substantially. Samet and his research team made seminal contributions to understanding the health effects of air pollution, the physiological effects of smoking and scientific basis of secondhand smoke, and the health effects of indoor pollution, among other areas (13). During his 14 years as chair, the faculty doubled, from 40 in 1994 to 79 in 2008, with only minor turnover. During this same period of time, the number of doctoral students doubled, with major increases in the number of master’s students. The finances of the department also grew in line with the increase in faculty. In part due to this growth, 2 deputy chairs were appointed (David Celentano and Terri Beaty) to assist the chair with the administration of the department, and a faculty executive committee, composed of elected and appointed faculty, was established to provide advice to the chair about anticipated policy changes that would affect students, staff, and faculty, as well as to establish strategic directions for the department.

Samet resigned in 2008 to become Chair of the Department of Preventive Medicine at the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California. At Dean Michael Klag’s request, Celentano became interim chair in August 2008 and was appointed chair in September 2009 following an international search. This appointment represented a shift in focus—Celentano is the first nonphysician to oversee the department—and reflects the current composition of the faculty, where PhDs greatly outnumber MDs (96 and 31, respectively). Epidemiology research today is conducted primarily on a team science basis, with most faculty holding doctoral degrees in epidemiology and related disciplines.

Today, the department has 8 educational tracks (Epidemiology of Aging, Cancer Epidemiology, Cardiovascular and Clinical Epidemiology, Clinical Trials and Evidence Synthesis, Environmental Epidemiology, General Epidemiology and Methodology, Genetic Epidemiology, and Infectious Disease Epidemiology), comprising 62 professorial faculty, 33 scientist faculty, 29 research associates, 2 instructors, and 1 senior lecturer. The department has grown from 79 in 2008 to 127 full-time faculty in 2019. There are approximately 90 master’s students and 60 doctoral students in residence.

We have recently made several changes to our doctoral curriculum in response to our changing student environment and the pace of change in the discipline. Seven years ago, we instituted a second-year doctoral student seminar, which meets weekly over the year, to move students towards development of a dissertation proposal. Three years later, we added a year-long first-year doctoral student seminar to provide opportunities for doctoral students to interact across academic tracks, several of which had only 1 or 2 matriculating students. We have also instituted an expectation that a PhD can be completed in 4 years, and over the past 5 years, we have reduced the time in residence from 5.6 years to 4.3 years.

CONCLUSION

The Department of Epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health is one of the oldest and largest academic teaching programs of epidemiology in the world. From its humble beginnings at the turn of the last century, it produced major discoveries and methods that are still in use today. There have been significant research discoveries in the fields of infectious and chronic diseases, the burgeoning importance of genetic epidemiology, and the several “-omics,” and the approaches used today are far more sophisticated than in the past. This is in part due to a major growth in computing power at greatly reduced cost. Cloud computing allows almost infinite data sets to be analyzed in real time, and epidemiologists now collaborate across many fields, including medicine, computer sciences, and spatial analysis. We have begun incorporating computational and systems modeling, machine learning, and artificial intelligence into epidemiologic research. Despite these major changes in how we do our work, we are still driven by the desire to understand the etiology of disease and how to harness what we know to prevent the onset of disease or ameliorate the consequences of disease once acquired. At our core, we are an educational institution, and student and postdoctoral training are integral to our core values. We wish to both fundamentally understand the pathogenesis of disease processes and use epidemiology in real-time public health practice to ultimately improve the health of populations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Author affiliations: Department of Epidemiology, Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland (David D. Celentano, Elizabeth Platz, Shruti H. Mehta).

This work was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health (grant AI094189).

We thank Prof. Moyses Szklo for his comments.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Abbreviations

- AIDS

acquired immune deficiency syndrome

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus.

REFERENCES

Appendix 1. EPIDEMIOLOGY (Johns Hopkins University, Circular of Summer Courses 1920)

W. H. Frost, M. D., Surgeon, U.S. Public Health Service, Resident Lecturer. Milton V. Veldee, M.D., Associate. W. Thurber Fales, S.B., C.P.H., Instructor.

The course is given in the second trimester, occupying eighteen hours a week.

It is designed to give students a view of the importance and possibilities of epidemiological study in extending the knowledge of infectious diseases, and to afford them training in methods, especially as applicable to such studies as may ordinarily be made in connection with administrative measures for the control of infectious diseases, utilizing the data ordinarily available to public health organizations.

The minimum requirements for admission to the course are a knowledge of the basic facts and principles of bacteriology, equivalent at least to what is given in the course in elementary bacteriology, together with sufficient knowledge of elementary statistical method. Subject to certain exceptions, students will be admitted to this course only after completing the required courses in bacteriology and vital statistics.

The work consists of:

A course of lectures presenting the principles and methods of epidemiological investigation and illustrating their application in special research and in such current study of infectious diseases as is a necessary part of the work of administrative health organization.

A course of selected collateral reading.

Class work, occupying approximately ten hours a week, in the analysis of crude epidemiological data, the presentation of conclusions and the planning of investigations.

Weekly conferences for the discussion of selected topics in connection with lectures, class work and collateral reading.

Demonstrations, arranged through the courtesy of the Baltimore City and Maryland State Departments of Health, of the work done by these organizations and associated agencies in the study and control of infectious diseases. These demonstrations are supplemented by individual field work on the part of students in the collection of epidemiological data from original sources, taking advantage of such opportunities for field work as may be presented at the time.

The preparation, by each student, of a brief thesis on an assigned subject in epidemiology.

Appendix 2. Centers in the Department of Epidemiology, 2019

Center for Clinical Trials and Evidence Synthesis

Center for Drug Safety and Effectiveness

Center for Public Health and Human Rights

Center on Aging and Health

Center to Eliminate Cardiovascular Health Disparities

Cochlear Center for Hearing and Public Health

Comstock Center for Public Health Research and Prevention

Evidence-Based Practice Center

Institute for Clinical and Translational Research

Johns Hopkins Biological Repository

Spatial Science for Public Health Center

StatEpi Coordinating Center

Welch Center for Prevention, Epidemiology, and Clinical Research

Wendy Klag Center for Autism and Developmental Disabilities