-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Richard C Oude Voshaar, Silvia D M van Dijk, New horizons in personality disorders—from neglect to necessity in geriatric care, Age and Ageing, Volume 54, Issue 4, April 2025, afaf066, https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afaf066

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Personality disorders, characterised by enduring and maladaptive patterns of behaviour, cognition and emotional regulation, affect 1 in 10 older adults. Personality disorders are frequently encountered in geriatric care considering their association with multimorbidity and increased health care utilisation. Patients with personality disorders often receive inadequate somatic health care due to (i) difficulties in expressing their actual symptoms and needs, (ii) challenging interactions with professionals, and (iii) non-compliance with medical treatment and lifestyle advice. Acknowledging personality disorders in geriatric care may improve treatment outcomes of somatic diseases. Since empirical evidence on personality diagnosis and treatment in older adults is scarce, we summarise future endeavours. First, the development of age-inclusive diagnostic tools should be prioritised to ensure comparability across age groups and facilitate longitudinal research over the lifespan. Second, evidence-based treatment approaches should be tailored to older people. Insight-oriented psychotherapies remain effective in later life considering sufficient level of introspection. Supportive and mediative therapies may better suit those with significant cognitive or physical impairments. Geriatric care models should be ideal for managing the complex needs of these patients when a consistent approach can be assured within the geriatric team as well as within the network considering the high level of interdisciplinary exchange needed. Third, considering the dynamic nature of personality disorders older adults should not be excluded from studies using novel technologies for real-time monitoring and personalised care. By addressing these gaps, the field can improve somatic treatment outcomes and uphold the dignity and well-being of older adults with personality disorders.

Key Points

Personality disorders are common, linked to multimorbidity, higher care use, yet often unrecognised in geriatric care.

Recognising specific personality disorders enables clear, empathetic and consistent responses from health care professionals.

Age-neutral diagnostic criteria and tools are essential for studying life transitions and comparing younger and older patients.

Randomised studies are needed to test age-adjusted psychotherapy for personality disorders in later life.

Excluding older adults from studies on innovative diagnostic or treatment technologies reflects ageism.

Introduction

Personality disorders are characterised by enduring patterns of behaviour, cognition and inner experience that deviate significantly from the expectations of an individual’s culture [1]. These patterns are pervasive, inflexible and typically emerge in early adulthood, affecting lifetime personal and social functioning across a range of situations. The pervasive nature of personality disorders implies that these disorders often persist into old age. In a representative population-based survey in the USA, the prevalence of a personality disorder was estimated at 13·2% for individuals aged 65–74 years, 10·4% for those aged 75–84 years and 10·7% for those aged 85 years or older [2]. Across all ages, personality disorders are associated with high levels of psychological distress, increased suicide risk, lower quality of life, physical and mental health problems, increased use of medical and informal care and premature mortality [3–7]. These associations underscore the importance of better addressing the needs of older individuals with personality disorders when they face somatic or (other) mental health issues, as well as exploring ways to mitigate the impact of the personality disorder itself. Considering the high prevalence rates [2] and the low detection rates in specialised mental health care [8], only a minority of older adults who meet the criteria for a personality disorder are likely to receive adequate mental health care for these conditions. Nonetheless, nearly all people have to interact with primary or specialised somatic health care professionals at some points in their life. This is even truer as people age due to increasing somatic multimorbidity. Personality-related issues often lead to interpersonal challenges that complicate interactions with somatic healthcare professionals.

Diagnosis

The development of personality disorders is best understood as an interplay between genetic predisposition and childhood adversity, such as trauma or neglect. Personality disorders are thought to be polygenic, with heritability estimates for specific traits ranging from 17% to 65% [9]. Genetic susceptibility may involve variations in genes related to neurotransmitter systems, emotional regulation, and impulse control, making individuals more vulnerable to developing maladaptive coping mechanisms or persistent behavioural patterns in response to early adversity and/or sociocultural circumstances [10, 11]. These coping mechanisms often reflect adaptive responses needed to survive adverse conditions in childhood but prove to be dysfunctional in the absence of such adversity or other circumstances. They typically become apparent as individuals mature and gain independence in adolescence. Social circumstances can shape the expression of personality pathology, either accentuating (e.g. poor support, stressors) or compensating (e.g. family support, social work environment) [12]. When compensatory mechanisms are lost through ageing (death of a spouse, retirement, physical illness), personality pathology may first become apparent in old age.

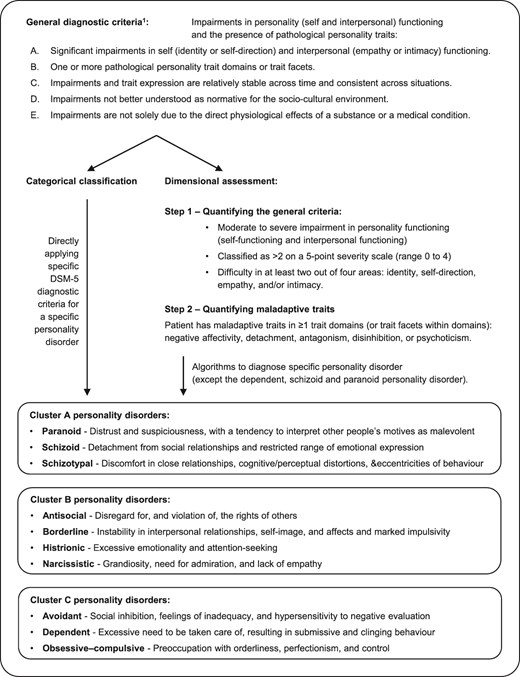

Adequate diagnostic procedures require a thorough biographical (hetero-)anamnesis from the individual as well as a close relative in addition to a mental health examination to explore actual symptoms and behaviour (see Figure 1). The various aspects that must be evaluated to diagnose a personality disorder are inherently dimensional in nature. In milder cases, it may be informative to observe a person’s natural behaviour when interacting in a group as well as to explore how they cope with stressful circumstances. Since the threshold from normative to pathological for the different traits and behaviours remains partly subjective, applying the LEAD standard may enhance diagnostic validity and reliability. LEAD is an acronym for ‘Longitudinal, Expert, All Data’ and refers to involving a team of expert clinicians conducting longitudinal assessments, utilising all available data from multiple sources [13, 14]. The LEAD standard is time-consuming and not always feasible in routine clinical practise or research. To standardise diagnostics, several self-report questionnaires and (semi-)structured interviews have been developed based on a plethora of personality theories [15]. For classification of personality disorders in research projects, the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Personality Disorders (SCID-5-PD) and Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-5 Alternative Model for Personality Disorders (SCID-5-AMPD) [16, 17] are most often used. For the DSM-5 AMPD are also self-reported questionnaires available for overall level of personality functioning (Level of Personality Functioning Scale Self-Report, LPFS-SR) [18] as well as maladaptive traits (Personality Inventory for DSM-5, PID-5) [19]. Shortened versions of these self-report questionnaires, designed for use in older persons, demonstrate acceptable psychometric properties [20, 21].

Accumulating research has contributed to the classification of ‘specific’ personality disorders in the DSM (version III through 5). The classification for ‘any’ personality disorder, however, is still based on expert consensus. This has not changed with the introduction of general diagnostic criteria in the DSM-IV and DSM-5, which include early onset, long duration, inflexibility and pervasiveness of symptoms and behavior [22]. Furthermore, empirical data increasingly challenge the categorical classification of personality disorders. The dimensional nature of personality traits, in line with the many personality theories, has led to the Alternative Model for Personality Disorders (AMPD) described in section III of the DSM-5 on ‘Emergent Measures and Models’ [1], which closely resembles the classification of personality disorders in the ICD-11 [23]. Intra- and interpersonal functioning becomes more apparent in the AMDP, which states that the core of personality disorders stems from issues in the ideas someone has of themselves and of interpersonal relationships. In a first diagnostic step, overall severity of personality pathology is estimated based on self and interpersonal functioning. Secondly, the constellation of personality traits is evaluated to describe the stylistic expression of the personality pathology.

Diagnosing personality disorders requires a high level of specialisation which falls beyond primary care or specialised geriatric services. Patients should be referred to specialised mental health care for proper diagnostics in case affective responses or interpersonal functioning are considered beyond average. A further complexity in geriatric mental health care is that not all diagnostic criteria for personality disorders fit for older people [24, 25]. Approximately 25% of the diagnostic criteria have a mismatch based on face validity [24] and 29% contain measurement bias in older age groups [25]. This might explain why the latent variable structure for each personality disorder shows a similar severity level of personality pathology whilst meeting a lower number of formal diagnostic criteria [25]. Proper diagnostics may help clinicians and relatives to understand the behavioural response of these patients better, give guidance to proper treatment of these patients in different health care settings, and may open the door for treatment in specialised mental health care to lessen suffering for themselves and their relatives.

Impact of personality disorders in mental health care

Personality disorders are rarely the main reason for referral to geriatric mental health care due to their ego-syntonic nature. Since most psychiatric disorders are associated with personality disorders, many patients seen in specialised mental health care suffer from a primary or comorbid personality disorder [26]. In the general population, estimates of comorbid personality disorders vary between 45% and 60% for the different types of mood disorders [27] and between 35% and 58% for the different anxiety disorders [28], being the most common psychiatric disorders in later life [29]. These figures align with studies amongst older persons referred to specialised mental healthcare, with reported prevalence rates of at least one personality disorder up to 33% in outpatient samples and up to 80% in inpatient samples [26].

Comorbidity of personality disorders is not inconsequential. Meta-analysis has shown that the presence of a comorbid personality disorder doubles the likelihood of nonresponse to treatment for mood disorders irrespective whether patients are treated with antidepressants, electroshock therapy or psychotherapy [30]. Albeit less studied, treatment results of anxiety disorders [31, 32], alcohol use disorders [33] and eating disorders [34] are also negatively affected in the presence of a personality disorder. In clinical practise, however, careful consideration is essential to prevent the mislabelling of therapy-resistant patients as having a personality disorder. Research on older adults, however, is sparse and confined to depression. A routine outcome monitoring study found that in older patients referred for depression treatment, the presence of any comorbid personality disorder resulted in poorer functional outcomes after one year of treatment than patients without personality comorbidity [8]. Additionally, cluster C personality disorders were linked to a delayed treatment response and worse long-term outcomes for depressive symptoms and functional recovery in a clinical trial on late-life depression [35].

Recent years, the evidence for psychotherapy to reduce psychological distress and to improve interpersonal, social and occupational functioning in people with personality disorders has increased substantially. Specialised psychotherapies like cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), schema therapy (ST), mentalisation-based therapy (MBT), dialectical behavioural therapy (DBT) and transference focused therapy are generally supported in guidelines, although evidence remains limited to relatively small clinical trials in highly specialised services (Table 1) [36–38].

| Therapy . | Mechanism of action . | Evidence for older adults . |

|---|---|---|

| CBT | Cognitive restructuring: identifying and changing distorted thought patterns that contribute to maladaptive behaviours. | Never been tested in older adults but feasibility and effectiveness of CBT for late-life psychiatric disorders has been widely acknowledged in the field and supported by several RCTs. |

| Behavioural activation: encouraging engagement in positive activities to improve mood and functioning. | ||

| Skill development: teaching coping skills, problem-solving techniques and emotional regulation strategies. | ||

| Dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) | Mindfulness: fostering present-moment awareness and acceptance of thoughts and feelings. | Feasibility for older adults has been demonstrated, as well as effectiveness in a small pilot RCT. |

| Emotional regulation: helping individuals understand and manage intense emotions. | ||

| Interpersonal effectiveness: improving communication skills and relationships. | ||

| Distress tolerance: developing strategies to cope with crises without resorting to harmful behaviours. | ||

| Schema therapy (ST) | Identification of schemas: recognising maladaptive schemas that influence behaviour and relationships. | Feasibility for older adults has been demonstrated by several observational studies. Effectiveness in later life is likely based on observational studies using a multiple baseline design as well as one well-powered RCT. |

| Schema mode work: exploring different emotional states and how they impact current functioning. | ||

| Experiential techniques: using imagery and role-play to address and heal from past traumas. | ||

| MBT | Mentalisation: enhancing the ability to understand oneself and others’ mental states, promoting empathy and insight. | Neither feasibility nor effectiveness has been examined in later life. |

| Exploration of relationships: examining interpersonal dynamics and how they affect emotions and behaviour. | ||

| Therapeutic alliance: building a strong therapeutic relationship to facilitate exploration and understanding. | ||

| Transference-focused psychotherapy (TFP) | Transference analysis: exploring the patient’s feelings and reactions towards the therapist to understand their interpersonal patterns. | Neither feasibility nor effectiveness has been examined in later life. |

| Reality testing: challenging distorted perceptions and beliefs about self and others. | ||

| Integration of split-off parts: helping individuals integrate conflicting aspects of their identity and emotions. | ||

| Psychodynamic therapy | Unconscious processes: exploring how unconscious thoughts and feelings influence behaviour and relationships. | Neither feasibility nor effectiveness has been examined in later life. |

| Defence mechanisms: identifying and understanding defence mechanisms that protect the individual from anxiety but may hinder functioning. | ||

| Transference and countertransference: utilising the therapeutic relationship to illuminate patterns from past relationships. |

| Therapy . | Mechanism of action . | Evidence for older adults . |

|---|---|---|

| CBT | Cognitive restructuring: identifying and changing distorted thought patterns that contribute to maladaptive behaviours. | Never been tested in older adults but feasibility and effectiveness of CBT for late-life psychiatric disorders has been widely acknowledged in the field and supported by several RCTs. |

| Behavioural activation: encouraging engagement in positive activities to improve mood and functioning. | ||

| Skill development: teaching coping skills, problem-solving techniques and emotional regulation strategies. | ||

| Dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) | Mindfulness: fostering present-moment awareness and acceptance of thoughts and feelings. | Feasibility for older adults has been demonstrated, as well as effectiveness in a small pilot RCT. |

| Emotional regulation: helping individuals understand and manage intense emotions. | ||

| Interpersonal effectiveness: improving communication skills and relationships. | ||

| Distress tolerance: developing strategies to cope with crises without resorting to harmful behaviours. | ||

| Schema therapy (ST) | Identification of schemas: recognising maladaptive schemas that influence behaviour and relationships. | Feasibility for older adults has been demonstrated by several observational studies. Effectiveness in later life is likely based on observational studies using a multiple baseline design as well as one well-powered RCT. |

| Schema mode work: exploring different emotional states and how they impact current functioning. | ||

| Experiential techniques: using imagery and role-play to address and heal from past traumas. | ||

| MBT | Mentalisation: enhancing the ability to understand oneself and others’ mental states, promoting empathy and insight. | Neither feasibility nor effectiveness has been examined in later life. |

| Exploration of relationships: examining interpersonal dynamics and how they affect emotions and behaviour. | ||

| Therapeutic alliance: building a strong therapeutic relationship to facilitate exploration and understanding. | ||

| Transference-focused psychotherapy (TFP) | Transference analysis: exploring the patient’s feelings and reactions towards the therapist to understand their interpersonal patterns. | Neither feasibility nor effectiveness has been examined in later life. |

| Reality testing: challenging distorted perceptions and beliefs about self and others. | ||

| Integration of split-off parts: helping individuals integrate conflicting aspects of their identity and emotions. | ||

| Psychodynamic therapy | Unconscious processes: exploring how unconscious thoughts and feelings influence behaviour and relationships. | Neither feasibility nor effectiveness has been examined in later life. |

| Defence mechanisms: identifying and understanding defence mechanisms that protect the individual from anxiety but may hinder functioning. | ||

| Transference and countertransference: utilising the therapeutic relationship to illuminate patterns from past relationships. |

aBased on guidelines for borderline personality disorders of the APA (USA) and NICE (UK), and the Dutch Interdisciplinary Guidelines for personality disorders [36–38].

| Therapy . | Mechanism of action . | Evidence for older adults . |

|---|---|---|

| CBT | Cognitive restructuring: identifying and changing distorted thought patterns that contribute to maladaptive behaviours. | Never been tested in older adults but feasibility and effectiveness of CBT for late-life psychiatric disorders has been widely acknowledged in the field and supported by several RCTs. |

| Behavioural activation: encouraging engagement in positive activities to improve mood and functioning. | ||

| Skill development: teaching coping skills, problem-solving techniques and emotional regulation strategies. | ||

| Dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) | Mindfulness: fostering present-moment awareness and acceptance of thoughts and feelings. | Feasibility for older adults has been demonstrated, as well as effectiveness in a small pilot RCT. |

| Emotional regulation: helping individuals understand and manage intense emotions. | ||

| Interpersonal effectiveness: improving communication skills and relationships. | ||

| Distress tolerance: developing strategies to cope with crises without resorting to harmful behaviours. | ||

| Schema therapy (ST) | Identification of schemas: recognising maladaptive schemas that influence behaviour and relationships. | Feasibility for older adults has been demonstrated by several observational studies. Effectiveness in later life is likely based on observational studies using a multiple baseline design as well as one well-powered RCT. |

| Schema mode work: exploring different emotional states and how they impact current functioning. | ||

| Experiential techniques: using imagery and role-play to address and heal from past traumas. | ||

| MBT | Mentalisation: enhancing the ability to understand oneself and others’ mental states, promoting empathy and insight. | Neither feasibility nor effectiveness has been examined in later life. |

| Exploration of relationships: examining interpersonal dynamics and how they affect emotions and behaviour. | ||

| Therapeutic alliance: building a strong therapeutic relationship to facilitate exploration and understanding. | ||

| Transference-focused psychotherapy (TFP) | Transference analysis: exploring the patient’s feelings and reactions towards the therapist to understand their interpersonal patterns. | Neither feasibility nor effectiveness has been examined in later life. |

| Reality testing: challenging distorted perceptions and beliefs about self and others. | ||

| Integration of split-off parts: helping individuals integrate conflicting aspects of their identity and emotions. | ||

| Psychodynamic therapy | Unconscious processes: exploring how unconscious thoughts and feelings influence behaviour and relationships. | Neither feasibility nor effectiveness has been examined in later life. |

| Defence mechanisms: identifying and understanding defence mechanisms that protect the individual from anxiety but may hinder functioning. | ||

| Transference and countertransference: utilising the therapeutic relationship to illuminate patterns from past relationships. |

| Therapy . | Mechanism of action . | Evidence for older adults . |

|---|---|---|

| CBT | Cognitive restructuring: identifying and changing distorted thought patterns that contribute to maladaptive behaviours. | Never been tested in older adults but feasibility and effectiveness of CBT for late-life psychiatric disorders has been widely acknowledged in the field and supported by several RCTs. |

| Behavioural activation: encouraging engagement in positive activities to improve mood and functioning. | ||

| Skill development: teaching coping skills, problem-solving techniques and emotional regulation strategies. | ||

| Dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) | Mindfulness: fostering present-moment awareness and acceptance of thoughts and feelings. | Feasibility for older adults has been demonstrated, as well as effectiveness in a small pilot RCT. |

| Emotional regulation: helping individuals understand and manage intense emotions. | ||

| Interpersonal effectiveness: improving communication skills and relationships. | ||

| Distress tolerance: developing strategies to cope with crises without resorting to harmful behaviours. | ||

| Schema therapy (ST) | Identification of schemas: recognising maladaptive schemas that influence behaviour and relationships. | Feasibility for older adults has been demonstrated by several observational studies. Effectiveness in later life is likely based on observational studies using a multiple baseline design as well as one well-powered RCT. |

| Schema mode work: exploring different emotional states and how they impact current functioning. | ||

| Experiential techniques: using imagery and role-play to address and heal from past traumas. | ||

| MBT | Mentalisation: enhancing the ability to understand oneself and others’ mental states, promoting empathy and insight. | Neither feasibility nor effectiveness has been examined in later life. |

| Exploration of relationships: examining interpersonal dynamics and how they affect emotions and behaviour. | ||

| Therapeutic alliance: building a strong therapeutic relationship to facilitate exploration and understanding. | ||

| Transference-focused psychotherapy (TFP) | Transference analysis: exploring the patient’s feelings and reactions towards the therapist to understand their interpersonal patterns. | Neither feasibility nor effectiveness has been examined in later life. |

| Reality testing: challenging distorted perceptions and beliefs about self and others. | ||

| Integration of split-off parts: helping individuals integrate conflicting aspects of their identity and emotions. | ||

| Psychodynamic therapy | Unconscious processes: exploring how unconscious thoughts and feelings influence behaviour and relationships. | Neither feasibility nor effectiveness has been examined in later life. |

| Defence mechanisms: identifying and understanding defence mechanisms that protect the individual from anxiety but may hinder functioning. | ||

| Transference and countertransference: utilising the therapeutic relationship to illuminate patterns from past relationships. |

aBased on guidelines for borderline personality disorders of the APA (USA) and NICE (UK), and the Dutch Interdisciplinary Guidelines for personality disorders [36–38].

More recent evidence suggests that specialist psychotherapy is not superior to ‘general psychotherapeutic treatment’ or ‘good psychiatric management’ [39, 40]. This equivalence, however, is only achieved for general treatment models grounded in a model of personality disorders that considers the specific challenges faced by patients and applies a consistent language and caring approach. Moreover, these general treatments still need to be manualized and delivered within a well-structured and specialised team to ensure effectiveness [39].

To our knowledge, only two randomised controlled trials (RTCs) have examined the effectiveness of psychotherapy for personality disorders in later life. These include a pilot study evaluating the effectiveness of DBT for older inpatients with persistent depression and comorbid personality disorders [41], and a well-powered RCT assessing the efficacy of group schema therapy (GST) for older outpatients with cluster B and/or C personality disorders [42]. DBT and GST both were superior to the usual care control conditions albeit reported effect-sizes were a bit lower compared to those found in younger people [41, 42].

Whilst prescription of psychotropic drugs for personality disorders is always off-label, older patients with personality disorders are frequently prescribed multiple psychotropic drugs [43]. Reasons for overprescription may be a lack of perceived clinical alternatives resulting in physician’s feelings of helplessness or indifference, unintended continuation after a temporary crisis, a general tendency to treat all symptoms pharmacologically, an attempt to keep patients assigned to their clinic, and finally ambiguity in guidelines [44, 45]. Psychotropic drugs, however, may have some merits to improve underlying traits or to suppress symptoms associated with a personality disorder. Training in the ‘relational aspects of prescribing’ is key for physicians, as acceptance of medication by patients largely depends on the relationship with their prescriber [46].

Table 2 summarises the recommendations from the Dutch and American multidisciplinary guideline arranged by prevailing symptoms or symptom clusters [36, 38]. Nonetheless, acknowledging symptom clusters of cognitive-perceptual disturbances, affective liability and impulsivity is not supported by the NICE guideline considering the lack of evidence and risk of overprescription [47]. Furthermore, evidence is entirely based on research in younger adults. Therefore, always discuss the target symptom for drug treatment, as well as the timing and method of evaluation, with the patient. Considering the risk of polypharmacy, guidelines generally recommend prescribing psychotropic drugs only for short-term periods and only adjunctive to psychotherapy [48]. Moreover, avoid polypharmacy and large-volume prescriptions of potentially toxic (e.g. tricyclic antidepressants) or addictive medications (e.g. benzodiazepines), perform a medication review every six months, and discontinue the drug when it proves to be insufficiently effective. Comorbid psychiatric disorders, however, should always be treated in accordance with the guideline for that specific disorder, despite its drop in effectiveness amongst those with a personality disorder.

Consensus-based preferred choices for pharmacological treatment of personality disordersa.

| Indication . | Recommendations . |

|---|---|

| Perceptual disturbances | Short-term use of low-dose antipsychotic drugs are considered first choice with no preference for typical or atypical antipsychotics. Dosages typically one third to a half of those required for antipsychotic treatment. Choice based on predicted side-effects (weight gain, lethargy, parkinsonism, cardiac side effects). Avoid use of benzodiazepines and tricyclic antidepressants. |

| Impulsivity | For acute treatment (hours, days), short-term use of low-dose antipsychotic drugs. For medium term effects, anti-epileptic drugs should be considered, with topiramate and lamotrigine being first choice and valproic acid being second choice. In case of treatment resistance, low-dose antipsychotic drugs can be considered (third choice). Avoid use of benzodiazepines and tricyclic antidepressants. |

| Affective liability | For persistent and invalidating mood swings, an SSRI, lamotrigine or an atypical antipsychotic drug can be considered. In case of a depressive disorder, an SSRI or SNRI is first choice, but in case treatment resistance, subsequent steps should be based on treatment algorithms for depressive disorder. In case of a low/depressed mood without a depressive disorder, treatment with an atypical antipsychotic drug or lamotrigine should be considered. In case of persistent anger/hostility, the anti-epileptics topiramate and lamotrigine are first choice and in case of treatment resistance, valproic acid or atypical antipsychotics are second choice. In case of persistent anxiety an SSRI or low-dose antipsychotic drug can be considered. With some reservations, benzodiazepines can also be considered. |

| Dissociation | No evidence for any drug. Avoid use of benzodiazepine and tricyclic antidepressants. |

| Indication . | Recommendations . |

|---|---|

| Perceptual disturbances | Short-term use of low-dose antipsychotic drugs are considered first choice with no preference for typical or atypical antipsychotics. Dosages typically one third to a half of those required for antipsychotic treatment. Choice based on predicted side-effects (weight gain, lethargy, parkinsonism, cardiac side effects). Avoid use of benzodiazepines and tricyclic antidepressants. |

| Impulsivity | For acute treatment (hours, days), short-term use of low-dose antipsychotic drugs. For medium term effects, anti-epileptic drugs should be considered, with topiramate and lamotrigine being first choice and valproic acid being second choice. In case of treatment resistance, low-dose antipsychotic drugs can be considered (third choice). Avoid use of benzodiazepines and tricyclic antidepressants. |

| Affective liability | For persistent and invalidating mood swings, an SSRI, lamotrigine or an atypical antipsychotic drug can be considered. In case of a depressive disorder, an SSRI or SNRI is first choice, but in case treatment resistance, subsequent steps should be based on treatment algorithms for depressive disorder. In case of a low/depressed mood without a depressive disorder, treatment with an atypical antipsychotic drug or lamotrigine should be considered. In case of persistent anger/hostility, the anti-epileptics topiramate and lamotrigine are first choice and in case of treatment resistance, valproic acid or atypical antipsychotics are second choice. In case of persistent anxiety an SSRI or low-dose antipsychotic drug can be considered. With some reservations, benzodiazepines can also be considered. |

| Dissociation | No evidence for any drug. Avoid use of benzodiazepine and tricyclic antidepressants. |

aBased on guidelines for borderline personality disorders of the APA (USA) and NICE (UK), and the Dutch Interdisciplinary Guidelines for personality disorders [36–38].

Consensus-based preferred choices for pharmacological treatment of personality disordersa.

| Indication . | Recommendations . |

|---|---|

| Perceptual disturbances | Short-term use of low-dose antipsychotic drugs are considered first choice with no preference for typical or atypical antipsychotics. Dosages typically one third to a half of those required for antipsychotic treatment. Choice based on predicted side-effects (weight gain, lethargy, parkinsonism, cardiac side effects). Avoid use of benzodiazepines and tricyclic antidepressants. |

| Impulsivity | For acute treatment (hours, days), short-term use of low-dose antipsychotic drugs. For medium term effects, anti-epileptic drugs should be considered, with topiramate and lamotrigine being first choice and valproic acid being second choice. In case of treatment resistance, low-dose antipsychotic drugs can be considered (third choice). Avoid use of benzodiazepines and tricyclic antidepressants. |

| Affective liability | For persistent and invalidating mood swings, an SSRI, lamotrigine or an atypical antipsychotic drug can be considered. In case of a depressive disorder, an SSRI or SNRI is first choice, but in case treatment resistance, subsequent steps should be based on treatment algorithms for depressive disorder. In case of a low/depressed mood without a depressive disorder, treatment with an atypical antipsychotic drug or lamotrigine should be considered. In case of persistent anger/hostility, the anti-epileptics topiramate and lamotrigine are first choice and in case of treatment resistance, valproic acid or atypical antipsychotics are second choice. In case of persistent anxiety an SSRI or low-dose antipsychotic drug can be considered. With some reservations, benzodiazepines can also be considered. |

| Dissociation | No evidence for any drug. Avoid use of benzodiazepine and tricyclic antidepressants. |

| Indication . | Recommendations . |

|---|---|

| Perceptual disturbances | Short-term use of low-dose antipsychotic drugs are considered first choice with no preference for typical or atypical antipsychotics. Dosages typically one third to a half of those required for antipsychotic treatment. Choice based on predicted side-effects (weight gain, lethargy, parkinsonism, cardiac side effects). Avoid use of benzodiazepines and tricyclic antidepressants. |

| Impulsivity | For acute treatment (hours, days), short-term use of low-dose antipsychotic drugs. For medium term effects, anti-epileptic drugs should be considered, with topiramate and lamotrigine being first choice and valproic acid being second choice. In case of treatment resistance, low-dose antipsychotic drugs can be considered (third choice). Avoid use of benzodiazepines and tricyclic antidepressants. |

| Affective liability | For persistent and invalidating mood swings, an SSRI, lamotrigine or an atypical antipsychotic drug can be considered. In case of a depressive disorder, an SSRI or SNRI is first choice, but in case treatment resistance, subsequent steps should be based on treatment algorithms for depressive disorder. In case of a low/depressed mood without a depressive disorder, treatment with an atypical antipsychotic drug or lamotrigine should be considered. In case of persistent anger/hostility, the anti-epileptics topiramate and lamotrigine are first choice and in case of treatment resistance, valproic acid or atypical antipsychotics are second choice. In case of persistent anxiety an SSRI or low-dose antipsychotic drug can be considered. With some reservations, benzodiazepines can also be considered. |

| Dissociation | No evidence for any drug. Avoid use of benzodiazepine and tricyclic antidepressants. |

aBased on guidelines for borderline personality disorders of the APA (USA) and NICE (UK), and the Dutch Interdisciplinary Guidelines for personality disorders [36–38].

Impact in somatic (geriatric) health care

Personality disorders are highly relevant to geriatric healthcare for three reasons. First, people with psychiatric disorders are at increased risk of having somatic multimorbidity, which is amplified in the presence of a personality disorder [5]. Personality disorders itself, in particular borderline personality disorder, have also been associated with somatic diseases, including cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, metabolic and gastrointestinal disease [49–53]. Second, when accounting for this higher level of somatic comorbidity, people with personality disorders make disproportionately greater use of somatic healthcare services [51, 54], whilst they are less compliant to medical treatment and lifestyle advice [51, 55]. The lack of compliance is generally assumed as an important contributor to worse somatic health outcomes and premature mortality, even when corrected for increased suicide rates [51, 55, 56]. Observational studies in younger adults have shown that improvement of personality pathology aligns with an improvement of lifestyle and decrease of health care utilisation [51]. Finally, recognising longstanding personality pathology should be distinguished from affective instability, poor impulse control, outbursts of aggression, apathy or paranoia resulting from a neurodegenerative or cerebrovascular disease, which in the DSM-5 can be classified as a ‘personality change due to another medical condition’ [1]. These symptoms, however, do not fit the etiological model of personality disorders (see above) and in our opinion should be considered as neuropsychiatric symptoms of brain diseases.

Physicians often categorise persons with personality disorders as ‘difficult patients’ by [57]. Geriatricians may face numerous challenges when treating older adults with personality disorders. Diagnosis can be difficult due to symptom overlap. Anxiety, depression and somatization stemming from personality disorders may mimic somatic symptoms, whilst communication barriers may lead to incomplete medical histories. With personality traits like impulsivity or distrust treatment adherence is often low affecting medication compliance and resistance to lifestyle changes needed for chronic disease management [51, 55]. Patient management may be more complex and time-consuming to navigate interpersonal conflicts, manipulative behaviours and emotional volatility, and also needs coordinating multidisciplinary care with psychologists, psychiatrists and social workers outside the medical domain [58, 59]. Behavioural factors, including substance abuse, poor diet and neglect of self-care routines, can exacerbate chronic conditions and increase complications [51, 55]. Medication management is challenging due to polypharmacy risks and increased sensitivity to side effects [44–46], necessitating careful balancing of benefits and risks. Social support issues, strained relationships and high rates of comorbid mental health conditions further complicate chronic disease management. Lastly, the emotional and cognitive load on geriatricians and primary care physicians can be significant, leading to stress, burnout and a need for specialised training in mental health and behavioural management for effective care [58].

Age-related aspects of personality disorders vary across the three main clusters of personality disorders (see Figure 1), each presenting unique challenges in later life. For individuals with cluster A personality disorders (the ‘odd, eccentric’ cluster), social isolation becomes increasingly problematic when functional limitations or illnesses necessitate assistance, as they may resist home care out of distrust or fear. When institutionalised, they may experience heightened agitation, aggression or even delusions. In cluster B personality disorders (the ‘dramatic, emotional, erratic’ cluster), impulsivity generally decreases with age, yet affective liability, dysthymic or dysphoric mood may intensify. These patients often show impulsivity concerning medication adherence and are more vulnerable to age-related stressors such as grief and retirement, sometimes causing divisions amongst caregivers. For those suffering from cluster C personality disorders (the ‘anxious, fearful’ cluster), there is often excessive reliance on medical and social support networks, whilst hesitancy can impede effective medical care and social referrals. Compulsiveness and rigidity may strain relationships with care providers, as these patients’ high standards are often unmet, and fear of rejection can contribute to social isolation and depression.

The transcendent principle in the patient-doctor relationship is that physicians should not react to the manifest dysfunctional behaviour but address their patient’s covert underlying core need (Table 3) [60]. See Appendix 1 in the Supplementary Data section for general recommendations when interacting with patients who have a (specific) personality disorder. These broad principles can be helpful for those with limited experience in managing personality disorders, whilst acknowledging that each patient interaction requires an individualised approach.

| Cluster . | Specific personality disorder . | Self-image . | Perception of others . | Behaviour . | Core need(s) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Paranoid | Inferior | User | Distrust and accuse | Safety |

| Schizoid | Loner | Pushy | Keeping distance | autonomy | |

| Schizotypal | Stranger | Threatening | isolate | Safety, anxiety reduction | |

| B | Narcissistic | Special | Inferior | Seek admiration | Self-admiration |

| Antisocial | Strong | Can be used | Intimidate | Domination | |

| Borderline | Bad and inferior | Abusive | Attract and repel | Autonomy, control and stable contact | |

| Histrionic | Attractive | Seductive | Charming, exaggerate and amuse | Admiring attention | |

| C | Dependent | Helpless | Supportive | Attach and adjust | Support |

| Avoidant | Incompetent | Critical | Avoiding contact and feelings | Acceptation and avoiding rejection | |

| Obsessive compulsive | Responsible | Irresponsible and incompetent | Control and seek perfection | Avoiding failure |

| Cluster . | Specific personality disorder . | Self-image . | Perception of others . | Behaviour . | Core need(s) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Paranoid | Inferior | User | Distrust and accuse | Safety |

| Schizoid | Loner | Pushy | Keeping distance | autonomy | |

| Schizotypal | Stranger | Threatening | isolate | Safety, anxiety reduction | |

| B | Narcissistic | Special | Inferior | Seek admiration | Self-admiration |

| Antisocial | Strong | Can be used | Intimidate | Domination | |

| Borderline | Bad and inferior | Abusive | Attract and repel | Autonomy, control and stable contact | |

| Histrionic | Attractive | Seductive | Charming, exaggerate and amuse | Admiring attention | |

| C | Dependent | Helpless | Supportive | Attach and adjust | Support |

| Avoidant | Incompetent | Critical | Avoiding contact and feelings | Acceptation and avoiding rejection | |

| Obsessive compulsive | Responsible | Irresponsible and incompetent | Control and seek perfection | Avoiding failure |

| Cluster . | Specific personality disorder . | Self-image . | Perception of others . | Behaviour . | Core need(s) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Paranoid | Inferior | User | Distrust and accuse | Safety |

| Schizoid | Loner | Pushy | Keeping distance | autonomy | |

| Schizotypal | Stranger | Threatening | isolate | Safety, anxiety reduction | |

| B | Narcissistic | Special | Inferior | Seek admiration | Self-admiration |

| Antisocial | Strong | Can be used | Intimidate | Domination | |

| Borderline | Bad and inferior | Abusive | Attract and repel | Autonomy, control and stable contact | |

| Histrionic | Attractive | Seductive | Charming, exaggerate and amuse | Admiring attention | |

| C | Dependent | Helpless | Supportive | Attach and adjust | Support |

| Avoidant | Incompetent | Critical | Avoiding contact and feelings | Acceptation and avoiding rejection | |

| Obsessive compulsive | Responsible | Irresponsible and incompetent | Control and seek perfection | Avoiding failure |

| Cluster . | Specific personality disorder . | Self-image . | Perception of others . | Behaviour . | Core need(s) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Paranoid | Inferior | User | Distrust and accuse | Safety |

| Schizoid | Loner | Pushy | Keeping distance | autonomy | |

| Schizotypal | Stranger | Threatening | isolate | Safety, anxiety reduction | |

| B | Narcissistic | Special | Inferior | Seek admiration | Self-admiration |

| Antisocial | Strong | Can be used | Intimidate | Domination | |

| Borderline | Bad and inferior | Abusive | Attract and repel | Autonomy, control and stable contact | |

| Histrionic | Attractive | Seductive | Charming, exaggerate and amuse | Admiring attention | |

| C | Dependent | Helpless | Supportive | Attach and adjust | Support |

| Avoidant | Incompetent | Critical | Avoiding contact and feelings | Acceptation and avoiding rejection | |

| Obsessive compulsive | Responsible | Irresponsible and incompetent | Control and seek perfection | Avoiding failure |

Addressing the challenges of managing older adults with personality disorders requires a multifaceted approach that prioritises integration, communication and support. Integrated care models that combine mental health and primary care enable more coordinated and holistic treatment that enhance outcomes. This requires regular exchanges between all participating professionals, along with clear definitions of each role in relation to the patient with a personality disorder. To ensure a smoother collaboration necessitates training and supervision. Clear, empathetic and predictable communication builds trust, facilitating a stronger therapeutic alliance with patients. Empowering patients through education and involvement in decision-making fosters greater adherence to treatment plans, and also involving family and caregivers provides essential support and oversight. Together, these strategies create a more supportive and effective framework for managing complex needs in geriatric care.

Future endeavours

Older people often remain excluded from studies on personality disorders, particularly those suffering from multimorbidity, frailty and cognitive impairments [36]. To advance this field of research within geriatrics requires innovative studies that include the specific aspects of older people in epidemiological, diagnostic and treatment studies.

First, geriatric and somatic healthcare providers often encounter older adults with undiagnosed or untreated personality disorders. Without adequate understanding of their core needs (Table 3), these patients are at risk of excessive medical interventions, iatrogenic harm and lower quality of life [59]. Training programmes that educate geriatric healthcare providers on recognising and managing personality disorders are essential. Psychiatric services should be readily available in geriatric settings to improve diagnostics and, if needed, to provide psychiatric care. A minimal, but crucial intervention involves giving tailored behavioural management advice to all other healthcare professionals involved in the patients’ care. This holistic, team-based approach may significantly enhance the quality of life for older adults with personality disorders and reduce the burden on healthcare systems.

Second, diagnostic criteria for personality disorders have been developed and validated in younger populations, ignoring the unique social contexts and distinct manifestations of these disorders in later life [61]. Future research should improve diagnostic tools to ensure they are both valid and reliable for older adults, whilst maintaining their comparability with younger populations. Rather than creating age-specific diagnostic criteria and assessment tools, it is crucial to adopt age-neutral frameworks. Age-specific criteria may impede comparative research between age groups and limit longitudinal studies examining transitions across the lifespan. Significant life transitions—such as retirement, loss of loved-ones or physical decline—can exacerbate the manifestation of personality pathology, making these periods critical for understanding and addressing personality disorders in older adults.

Third, personality pathology is a significant predictor of nursing home admission [62, 63], with up to 80% of residents with mental-physical multimorbidity having at least one maladaptive personality trait [64]. Yet, there is a stark lack of empirical research on managing these conditions in this setting and once admitted these individuals often face barriers to appropriate care [65]. Traditional psychotherapies, particularly those requiring high levels of mentalisation and introspection, may not be feasible due to cognitive or functional limitations. Mediative therapy delivered through the nursing team may offer promising alternatives [66, 67] as well as supportive approaches align the principles of ‘good psychiatric management’ of personality disorders [68]. Refining and validating such models for long-term care settings is a pressing research priority. RCTs are needed to assess the effectiveness of these approaches in improving outcomes for both residents and care providers.

Fourth, treatment of late-life personality disorders is underdeveloped. For older adults living independently and with good reflective capacity, traditional psychotherapies (see Table 1) remain first choice, much like in younger populations. However, for those with lower levels of mentalisation or introspection, severe personality pathology or significant somatic and cognitive challenges, supportive and mediative therapies may be more appropriate. Developing and testing such models through RCTs is essential to establish evidence-based guidelines for this population. Additionally, research should explore hybrid approaches that combine psychotherapy with pharmacological or psychosocial interventions tailored to the unique needs of older adults.

Fifth, one hallmark of personality disorders is sensitivity to stress and fluctuating symptomatology. Under ideal circumstances, individuals with personality disorders may function relatively well. During stressful events or when past traumas are triggered, vulnerabilities such as emotional instability, impulsivity, self-harming behaviour, substance abuse or aggression often emerge. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA), which monitors triggers and symptoms in real-time, is ideally suited to understanding these fluctuations within individuals [69, 70]. In long-term care settings, observer-based research using cameras or wearable devices could provide valuable insights into how environmental stressors influence symptomatology (e.g. [71]). This approach is promising for the development of tailored interventions to mitigate stress-induced exacerbations of personality pathology in older adults.

Sixth, studies on late-life personality disorders should not refrain innovative methodologies and technologies. Longitudinal studies are crucial for understanding how personality pathology evolves with ageing and life transitions. Cross-sectional studies, whilst informative, cannot capture the nature of personality dynamics and its interaction with ageing processes. In this respect, digital tools such as wearables, mobile applications and remote monitoring systems can revolutionise data collection and intervention delivery [70]. For instance, wearable devices could monitor physiological stress markers in real-time, whilst mobile apps might facilitate self-reporting of mood or behaviour changes [72]. Such technologies not only enhance data accuracy but may also empower older adults to actively engage in their care [73, 74]. Participation in studies evaluating experimental techniques in psychotherapy are also crucial for geriatric care. For example, studies leveraging artificial intelligence or avatars hold the potential to enhance therapeutic effects by personalising interventions, improving accessibility and fostering experiential learning [75]. Older persons are often excluded from e-health interventions based on stereotypes that older persons are not digitally proficient. Nonetheless, pilot studies on online psychotherapy for older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic have shown promising results with respect to feasibility and acceptability [76].

Finally, most existing research on personality disorders is conducted in Western societies and often neglect cultural and socioeconomic diversity [77]. Cultural norms and values significantly influence how personality pathology manifests and is perceived [11, 77]. Future studies must adopt a global perspective, especially given the increasing cultural diversity within ageing populations worldwide.

Conclusion

Recognising personality disorders in older patients is essential as treating older patients with chronic somatic diseases and personality disorders requires a comprehensive, patient-centred approach that addresses their physical, social and psychological needs. Geriatric care models focus on integrated care, ideally beyond boundaries between mental and somatic health care, beyond boundaries of different echelons like primary and secondary health, beyond boundaries of independently living older persons and those in long-term care facilities, and finally beyond boundaries between the medical and social domain. As outlined above, this may be very complicated to achieve for older people with personality disorders due to the lack of proper diagnostics and need for a consistent approach of the different professionals involved.

Research on personality disorders in older adults, however, is in its infancy. From refining diagnostic criteria to developing innovative treatment models and leveraging cutting-edge technologies, the potential for impactful discoveries is vast. By prioritising age-neutral diagnostic frameworks, focusing on vulnerable populations in long-term care, and embracing interdisciplinary and innovative research methodologies, we can significantly improve the quality of care and outcomes for older adults with personality disorders. As the global population ages, the demand for evidence-based care for older adults with personality disorders will only grow. Addressing this gap in research is not just a scientific imperative—it is a moral one, ensuring that older adults with personality disorders receive the understanding, respect and care they need and deserve.

Declaration of Conflicts of Interest:

None declared.

Declaration of Sources of Funding:

None declared.

Comments