-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Victoria L Chuen, Saumil Dholakia, Saurabh Kalra, Jennifer Watt, Camilla Wong, Joanne M-W Ho, Geriatric care physicians’ perspectives on providing virtual care: a reflexive thematic synthesis of their online survey responses from Ontario, Canada, Age and Ageing, Volume 53, Issue 1, January 2024, afad231, https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afad231

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

During the COVID-19 pandemic, telemedicine was widely implemented to minimise viral spread. However, its use in the older adult patient population was not well understood.

To understand the perspectives of geriatric care providers on using telemedicine with older adults through telephone, videoconferencing and eConsults.

Qualitative online survey study.

We recruited geriatric care physicians, defined as those certified in Geriatric Medicine, Care of the Elderly (family physicians with enhanced skills training) or who were the most responsible physician in a long-term care home, in Ontario, Canada between 22 December 2020 and 30 April 2021.

We collected participants’ perspectives on using telemedicine with older adults in their practice using an online survey. Two researchers jointly analysed free-text responses using the 6-phase reflexive thematic analysis.

We recruited 29 participants. Participants identified difficulty using technology, patient sensory impairment, lack of hospital support and pre-existing high patient volumes as barriers against using telemedicine, whereas the presence of a caregiver and administrative support were facilitators. Perceived benefits of telemedicine included improved time efficiency, reduced travel, and provision of visual information through videoconferencing. Ultimately, participants felt telemedicine served various purposes in geriatric care, including improving accessibility of care, providing follow-up and obtaining collateral history. Main limitations are the absence of, or incomplete physical exams and cognitive testing.

Geriatric care physicians identify a role for virtual care in their practice but acknowledge its limitations. Further work is required to ensure equitable access to virtual care for older adults.

Key Points

Telemedicine can serve to increase the accessibility of care, be used to provide follow-up care, and to obtain collateral history.

Key barriers to using telemedicine with older patients relate to sensory impairments and the accessibility of technology.

Virtual assessments are limited by the extent of physical examinations or cognitive testing that can be performed.

Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic, virtual care became widespread across many health services to minimise in-person visits and viral spread [1–4]. In Ontario, Canada, virtual care can be synchronous (telephone calls and videoconference visits) or asynchronous (eConsults, an online platform, which allows referring physicians to directly consult specialists for advice without the patient being present).

Although the use of telemedicine has increased during the pandemic, it remains unclear which tools are perceived as appropriate for the scope of practice within geriatrics and caring for older adults. Patients and caregivers rely on clinicians to determine when virtual care is an appropriate choice, over in-person care [5]. It has been shown that a hybrid model of in-person and virtual care will likely remain within geriatrics, and many other specialties, beyond the pandemic [5]. As such, the purpose of this study was to understand the experiences and perspectives of geriatric care physicians on the various telemedicine tools: telephone, videoconferencing and eConsults, in providing geriatric care to older adults.

Methods

We carried out a mixed quantitative and qualitative online survey for our study. In this manuscript, we focus on the qualitative results of our study. This report follows the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys guidelines [6]. We also report on the relevant items from the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research, though reporting on some criteria is limited by the absence of interview/focus group data, given the use of an online survey in this study. We obtained ethics approval from McMaster University Research Ethics Board (HiREB) (Project #11154).

Participant recruitment

We used convenience sampling by advertising our research project to potential participants through email lists catered towards physicians providing geriatric care. Our inclusion criteria included physicians who were certified in Geriatric Medicine (Internal Medicine-trained physicians), Care of the Elderly (Family Medicine physicians who completed an additional year of training in geriatrics) or who were the most responsible physician in a long-term care home for at least ten older adult patients. All participants were practicing in Ontario, Canada and had experience using virtual care in their geriatric practice. Virtual care was defined as being any one of the following three modalities: telephone visits, video visits and eConsults. We excluded retired physicians, as they may not have practiced during the pandemic, trainees (i.e. resident doctors, medical students), who have less autonomy over the format of care delivery, and geriatric psychiatrists, due to their earlier adoption of virtual care and through telepsychiatry [7, 8]. We recruited participants and collected our data between 22 December 2020 and 30 April 2021.

Survey design

We hosted our online survey through SurveyMonkey©, which automatically captures survey responses that can be downloaded for analysis. Our survey was designed by two primary investigators (V.C and J.H) and contained three sections, each for one of the three modalities of virtual care. Telephone visits were defined as clinical encounters completed over the telephone between the provider and the patient and/or their caregivers. Video visits were defined as clinical encounters completed through videoconferencing between the provider and the patient. eConsults were defined as a consultation provided through the Champlain Building Access to Specialists through eConsultation platform, the Ontario Telemedicine Network (OTN) or email to a referring physician and did not include making a request for an eConsult. We prompted participants to share their perspectives on using each tool with regards to their reason for implementing the tool, perceived benefits, ease of use, limitations, and barriers against using the tool within their scope of geriatric practice. We collected study participant demographics including age group, sex, specialty type, location of practice, type of practice (i.e. academic or community) and years in practice. Our survey is available in our supplementary data (Appendix 1).

We tested the survey’s face validity and usability with an expert panel consisting of three geriatricians, a Care of the Elderly physician, and a geriatric psychiatrist. We randomised the presentation of questions pertaining to each virtual care tool to avoid low or incomplete completion responses for any one tool, due to survey fatigue. We utilised adaptive questioning based on initial screening questions, and therefore the number of questions per page varied from 1 to 7 questions, and the number of pages varied from 4 to 15 pages. At the end of each survey page, participants were prompted with a completeness check to ensure all mandatory fields were completed. Participants were allowed to edit their responses prior to final submission but were not provided with a summary of their responses prior to ending the survey. Participants were not permitted to return to the survey after submission to edit their responses.

Survey administration

We sent a personalised link to an online survey to all participants who agreed to be approached for our research. No relationships were established between the researchers and the study participants, though it is possible that respondents may have previously interacted with the researchers involved in the study due to the small community of geriatricians in Ontario, Canada. Survey completion was voluntary. We did not require a password to access our open survey. We presented the study consent form on the first page of the survey, which outlined the purpose of the study, approximate length of time to complete the survey, information about data storage and the study investigators. Participants had to read and click-through the consent form before they were presented with the survey questions. We prohibited multiple responses from the same participant by providing participants with a unique survey link to prevent duplicate entries, rather than using cookies or collecting any Internet Protocol data. Survey responses could not be linked back to the initial email address it was sent to, allowing responses to be fully anonymised.

Declaration of funding

We received project funding, which was used to provide incentives to complete the survey. On the first page of the survey, our study information and consent page notified potential participants that survey completion would result in a reward of a $20 gift card. To preserve anonymity of survey responses, once the survey was completed, we provided a separate survey link to collect contact information to distribute the gift cards. The funding group had no role in the design, execution, analysis, and interpretation of data, or writing of the manuscript.

Analysis

All data was password protected against unauthorised access and only researchers listed in the ethics protocol had access to the raw and analysed data. The research team included five authors with a clinical background in geriatric care. At the time of study completion, V.C (MD) was a female senior resident trainee in Internal Medicine, S.D (MHSc, MD) was a male Geriatric Clinical Pharmacology & Psychiatry Fellow and qualitative researcher, S.K (MD) was a male Care of the Elderly family physician and long-term care medical director, J.W (PhD, MD) was a female consultant geriatrician and clinical epidemiologist, C.W (MSc, MD) was a female consultant geriatrician and researcher, and J.H (MHSc, MD) was a female consultant geriatrician, clinical pharmacologist and researcher.

Two investigators (V.C and S.D) jointly and collaboratively performed the 6-phase reflexive thematic analysis qualitative research methodology [9, 10]. Reflexive thematic analysis is a method which allows researchers to participate actively in the qualitative analysis and generate meaning from a dataset, through their own interpretation, rather than assuming that a single truth lies within the data itself [11]. Our goal was to understand the perspectives of geriatric care physicians on using each of the telemedicine tools in caring for older adults.

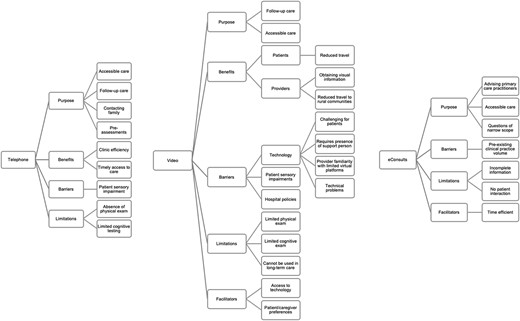

V.C and S.D familiarised themselves with the survey responses and performed line-by-line coding. We included all survey responses in our thematic analysis, including partially complete surveys and all responses were analysed according to the tool referred to (i.e. telephone, video or eConsults) in the original survey question. Codes were jointly identified by V.C and S.D, grouped based on similarities and then indexed accordingly using a visual map (see supplementary data, Appendix 2 for sample). Themes were then identified from the charting of codes. The themes were produced around multiple organising concepts that the researchers interpreted from the data.

The analysis was reflexive, as we aimed to achieve a deeper understanding of the data, rather than just achieve consensus of meaning. As is the case in reflexive thematic analysis, the final analysis was derived from V.C and S.D’s combined interpretation of the data, influenced by their theoretical assumptions of the analysis. During the process of conceptualisation of the study and subsequently at the stage of familiarising with the data set, V.C tended towards a more deductive and essentialist assumptions to ensure the open-coding contributed to producing themes relevant to the research question, while S.D adopted a constructionist, experiential and inductive orientation, thereby adding richness to interpretation of the data [10]. Following perspectives raised by Braun and Clarke [12], our aim was to generate meaning from the interpretation of data, rather than establishing a particular quantity of data to support a particular theme; as such, we did not recruit participants on the basis of achieving ‘data saturation’.

In the generation of our themes, we defined the term ‘purpose’ as meaning to meet a particular objective, ‘benefit’ as the advantages perceived, ‘barrier’ as the obstacles preventing use, ‘shortcomings’ as the flaws or limitations, and ‘facilitators’ as the factors that make an action easier.

In a separate manuscript, we reported upon the major themes that were generated regarding the use of telemedicine in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic [13]. This manuscript presents the major themes generated, which represent a more generalised perspective of using telemedicine, namely telephone visits, video visits or eConsults, by geriatric care physicians (Figure 1).

Coding tree depicting major themes identified for telephone visits, video visits and eConsults based on free-text survey responses.

Results

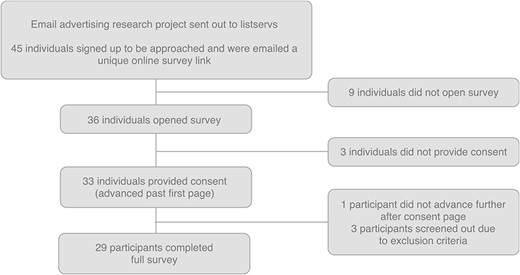

We had 45 participants sign up to be approached for our online survey, and 33 individuals provided their consent to participate. Three individuals were excluded for not meeting inclusion criteria, and one did not advance further than the consent page, resulting in 29 completed survey responses (Figure 2). The participation rate, defined as the number of participants who visited the first page of the survey over the number of individuals who agreed to be approached for the survey [6] was 80%. The survey completion rate, defined as the number of participants who completed the entire survey divided by the number who provided consent [6] was 87.9%.

Participant characteristics

Participants included geriatricians (75.9%), physicians working in long-term care (13.8%) and Care of the Elderly physicians (10.3%). The sample included 58.6% females and 34.5% males, and 6.9% of individuals who preferred not to share their sex. Respondents included both geriatric care physicians working in community (58.6%) and academic practices (41.4%) (Table 1). Most participants had previous experience using the telephone (96.6%), followed by videoconferencing (86.2%) and eConsults (64%).

| Baseline characteristic . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Scope of practice | |

| Geriatrician | 22 (75.9) |

| Care of the elderly physician | 3 (10.3) |

| Long-term care home physician | 4 (13.8) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 10 (34.5) |

| Female | 17 (58.6) |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 (6.9) |

| Age | |

| 20–30 years | 2 (6.9) |

| 31–40 years | 12 (41.4) |

| 41–50 years | 6 (20.7) |

| 51–60 years | 4 (13.8) |

| 61–70 years | 5 (17.2) |

| Ontario Health Region | |

| West | 12 (41.4) |

| Central | 3 (10.3) |

| Toronto | 5 (17.2) |

| North | 2 (6.9) |

| East | 6 (20.7) |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (3.4) |

| Type of practice | |

| Community | 17 (58.6) |

| Academic | 12 (41.4) |

| Years in practice | |

| 0–10 years | 14 (48.3) |

| 11–20 years | 6 (20.7) |

| 21–30 years | 3 (10.3) |

| >30 years | 6 (20.7) |

| Baseline characteristic . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Scope of practice | |

| Geriatrician | 22 (75.9) |

| Care of the elderly physician | 3 (10.3) |

| Long-term care home physician | 4 (13.8) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 10 (34.5) |

| Female | 17 (58.6) |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 (6.9) |

| Age | |

| 20–30 years | 2 (6.9) |

| 31–40 years | 12 (41.4) |

| 41–50 years | 6 (20.7) |

| 51–60 years | 4 (13.8) |

| 61–70 years | 5 (17.2) |

| Ontario Health Region | |

| West | 12 (41.4) |

| Central | 3 (10.3) |

| Toronto | 5 (17.2) |

| North | 2 (6.9) |

| East | 6 (20.7) |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (3.4) |

| Type of practice | |

| Community | 17 (58.6) |

| Academic | 12 (41.4) |

| Years in practice | |

| 0–10 years | 14 (48.3) |

| 11–20 years | 6 (20.7) |

| 21–30 years | 3 (10.3) |

| >30 years | 6 (20.7) |

LTC = long-term care; NH = nursing home

| Baseline characteristic . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Scope of practice | |

| Geriatrician | 22 (75.9) |

| Care of the elderly physician | 3 (10.3) |

| Long-term care home physician | 4 (13.8) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 10 (34.5) |

| Female | 17 (58.6) |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 (6.9) |

| Age | |

| 20–30 years | 2 (6.9) |

| 31–40 years | 12 (41.4) |

| 41–50 years | 6 (20.7) |

| 51–60 years | 4 (13.8) |

| 61–70 years | 5 (17.2) |

| Ontario Health Region | |

| West | 12 (41.4) |

| Central | 3 (10.3) |

| Toronto | 5 (17.2) |

| North | 2 (6.9) |

| East | 6 (20.7) |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (3.4) |

| Type of practice | |

| Community | 17 (58.6) |

| Academic | 12 (41.4) |

| Years in practice | |

| 0–10 years | 14 (48.3) |

| 11–20 years | 6 (20.7) |

| 21–30 years | 3 (10.3) |

| >30 years | 6 (20.7) |

| Baseline characteristic . | n (%) . |

|---|---|

| Scope of practice | |

| Geriatrician | 22 (75.9) |

| Care of the elderly physician | 3 (10.3) |

| Long-term care home physician | 4 (13.8) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 10 (34.5) |

| Female | 17 (58.6) |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 (6.9) |

| Age | |

| 20–30 years | 2 (6.9) |

| 31–40 years | 12 (41.4) |

| 41–50 years | 6 (20.7) |

| 51–60 years | 4 (13.8) |

| 61–70 years | 5 (17.2) |

| Ontario Health Region | |

| West | 12 (41.4) |

| Central | 3 (10.3) |

| Toronto | 5 (17.2) |

| North | 2 (6.9) |

| East | 6 (20.7) |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (3.4) |

| Type of practice | |

| Community | 17 (58.6) |

| Academic | 12 (41.4) |

| Years in practice | |

| 0–10 years | 14 (48.3) |

| 11–20 years | 6 (20.7) |

| 21–30 years | 3 (10.3) |

| >30 years | 6 (20.7) |

LTC = long-term care; NH = nursing home

Barriers to using telemedicine tools

Survey respondents identified challenges at the technological, patient and structural level, which may prohibit or deter the use of telemedicine in geriatric care.

Technology use

Participants identified access to technology as a barrier to telemedicine since the use of virtual care tools and internet connection are necessary by both the geriatric care physicians and patients. Even when technology is available, participants perceived their patients found videoconferencing difficult to use. The presence of a support person was often necessary to help overcome this barrier which was noted to be a challenge for patients without caregivers, or who resides in long-term care.

“Many patients are not familiar with their use and may not even own a computer. This would necessitate the presence of a caregiver or a family member.”— Respondent #32, Geriatrician

“Not a very useful application for [long-term care]. Lack of availability of equipment and staff to facilitate visits.”— Respondent #14, Physician in long-term care

Participants identified a preference towards virtual platforms that were user-friendly and familiar, such as Zoom© and Facetime©.

“I see that it can be useful- but only now that the technology has improved (to be honest, OTN was cumbersome before and new methods, included Zoom integrated into [electronic medical records] has made the interface easier)”— Respondent #20, Geriatrician

However, even if the appropriate set-up was facilitated for the video encounter, technological problems could still arise during the video visit thereby limiting the success of the patient encounter.

“Sometimes hard to get family to connect, or there are Wi-Fi issues at patient’s home.” – Respondent #20, Geriatrician

Patient-specific barriers

Geriatric care physicians found challenges with using telephone and video visits in patients with sensory impairments.

“Even with assistance, there are challenges due to hearing impairment, vision impairment, lack of familiarity with communicating over a virtual medium.”— Respondent #3, Geriatrician

Structural barriers

Participants noted hospital policies might also prevent implementation of telemedicine tools into geriatric practice.

“Practice variability is related to whether there has been any corresponding promotion of virtual care amongst hospital clinical support.” – Respondent #17, Geriatrician

Not all survey respondents were using eConsults in their geriatric practice. A major barrier was that physicians felt they already had a sufficient volume of other clinical responsibilities, which did not allow for additional time to providing eConsults.

“It’s hard to keep up with regular referrals volume – did not want to add on something else.”— Respondent #17, Geriatrician

Facilitators towards using telemedicine

Related to the identified barriers, survey respondents identified in contrary, the factors that enable use of telemedicine in geriatric care.

Access to technology and support

The access to technology and having assistance offered by their practice location to overcome the initial challenges with setting up video visits helped to facilitate its implementation.

“Facilitated access to technology at my practice site made it easy.” – Respondent #17, Geriatrician

Patient and caregiver preference

Additionally patient or caregiver-expressed preference encouraged physicians to choose telemedicine over another format.

“Some patients and their families will in fact demand their [telemedicine] use due to convenience factors” and so “if a patient prefers this modality, I am happy to offer” – Respondent #11, Geriatrician

Efficiency of eConsults

Participants who did use eConsults, specifically identified the efficiency related to its use enabled their use in their geriatric practice.

“I thought they [eConsults] were efficient and helpful” and “find they are on the whole very good questions which can be responded to via email”.— Respondent #11, Geriatrician

Benefits of telemedicine tools

Efficiency of telephone visits

Following use of telemedicine, the main perceived advantage of telephone visits was related to time. Participants identified improved time efficiency from their practice standpoint, which thereby was interpreted to help facilitate timely access of care to patients.

[Implemented telephone visits] “for convenience for my patients, and efficiency for myself and my office.” – Respondent #13, Care of Elderly Physician

[Implemented telephone visits] “for shorter visits, more focused care, and for challenging circumstances. Also to manage my own caseload because I couldn’t always fit people in into clinic slots/days but needed brief contact and to reduce burden to frail seniors when not necessary.” – Respondent #27, Geriatrician

Video visits reduce travel

A perceived benefit of video visits was the ability to eliminate the need for patients to travel to their appointments and for geriatric specialists to travel to rural areas.

[Implemented video visits] “mainly due to the distance. It was hard to drive 2 hours up north in the winter and I wanted to continue providing consults to under serviced areas.”— Respondent #15, Geriatrician.

[Video visits are] “very useful as an alternative to home visits and clinic visits. Should be offered to most patients if they have limited access to clinic.”— Respondent #26, Geriatrician

Video visits offer additional visual information

Participants also felt that the visual aspect of videoconferencing allowed for specific benefits, such as allowing for some physical exam components to be completed, as well as visualising the patient’s home environment.

“Some patients more at ease in home, and definitely more convenient for many families. Seeing patient in their own home gives a lot of valuable info.”— Respondent #17, Geriatrician.

Telemedicine serves various purposes in geriatric care

Accessibility to care

Geriatric care physicians identified telemedicine could be used to improve access to geriatric care, as related to the perceived benefits noted earlier of improved efficiency and the reduction of travel. Telemedicine can reduce physical barriers for patients living in geographically under-serviced areas or with limited mobility, who might be unable to attend an in-person appointment.

“Patients feel they have access to their physician and can get their questions answered in a timely manner.” [Regarding telephone visits]— Respondent #9, Care of the Elderly physician.

“Allowed patients to be seen without having to travel to Barrie or even further to see a Geriatrician.”— Respondent #15, Geriatrician.

Participants felt eConsults specifically serve a purpose to provide timely advice to primary care physicians on questions with a narrow scope irrespective of location.

“For a quick answer eConsults serves a purpose without the patient waiting several months.”— Respondent #15, Geriatrician.

Follow-up care

Participants identified both telephone and video visits were useful for providing follow-up care.

“They [telephone visits] are very useful for follow-ups.”— Respondent #18, Geriatrician.

[Telephone visits are] “good for quick follow ups, like checking on medication tolerance”— Respondent #29, Geriatrician.

[Video visits] “allow for … follow-up of chronic issues.”— Respondent #13, Care of Elderly physician.

Obtaining collateral history

Telephone visits were felt to be useful in obtaining collateral history from multiple caregivers, or to complete pre-assessments.

“It is easy because I can contact the caregiver or caregiver is also on the line to provide collateral. Sometimes spouse would be there in person and not as helpful in providing collateral as children and now I can have everyone on the line to provide more insight.”— Respondent #15, Geriatrician.

Shortcomings of using telemedicine in geriatric care

Although telemedicine serves a purpose in geriatric care, participants also identified an overarching concern regarding the comprehensiveness of assessments being incomplete, which can then limit the scope of the geriatric assessment.

Specifically, participants felt the absence of physical exam and traditional cognitive testing resulted in incomplete assessments compared to in-person assessments. Participants felt this limited the use of telephone visits in providing a wide scope of geriatric care, such as new consultations.

“Telephone consults are possible, but limit diagnostic certainty with consultations.”— Respondent #18, Geriatrician.

[Virtual care] “has met a need and has a place in the future but will never completely replace the need for in person medicine.”— Respondent #7, Geriatrician.

Despite allowing for partial physical exams, participants stated that video visits remain inadequate. As a tool, many identified specific circumstances where video visits would be inappropriate, such as patients requiring in depth physical exams or cognitive testing and new consultations. It was also not felt to be appropriate for patients in long-term care.

“Ultimately, I felt uncomfortable leaving some residents – older cardiac in particular – 'unseen’. Presentations are atypical and physical assessment in person subsequently confirmed that we were missing subtle signs of decompensation” . . . and “it is not sufficient, especially for conditions that benefit from physical assessment.” . . . “such as heart failure and movement disorders.”— Respondent #5, Geriatrician.

“Not useful for routine rounds for attending physicians with staff.” [Regarding care delivered in long-term care]. – Respondent #14, Physician in long-term care.

Many also felt the absence of direct patient contact was a limitation of eConsults. This results in incomplete information gathered about the patient and clinical scenario, which in certain circumstances, some deemed limited or not suitable for geriatric care.

“Questions in geriatrics are often hard to answer without seeing a patient and doing a complete assessment. However, I think there is still a lot of potential, for example regarding medication management”— Respondent #29, Geriatrician.

“Without seeing and talking to a patient, they are ultimately inappropriate.”— Respondent #5, Geriatrician.

Discussion

The pandemic necessitated a shift towards virtual care, providing many geriatric care physicians with an opportunity to use various telemedicine tools in their practice. This is the first qualitative study to explore the experiences and perspective of geriatric care physicians across both rural and urban settings on using the different telemedicine tools available in Ontario, Canada. In our study, geriatric care physicians identified difficulties with technology, patient sensory impairment, inadequate hospital support and pre-existing high patient volumes as barriers against using telemedicine. Conversely, the presence of a caregiver, patient expressed preferences for using telemedicine, and efficiency of eConsults were identified as facilitators that enabled its use. The perceived benefits of telemedicine included improved efficiency, reducing the need for travel and obtaining additional visual information through video visits. Ultimately, survey respondents felt that telemedicine serves a purpose in geriatric care in providing older adults with timely and accessible care, for follow-up appointments and to obtain collateral history. However, a main limitation is the incompleteness of assessments due to the absence of, or incomplete, physical exams and cognitive tests. We hope our study can provide information to guide the use of telemedicine in geriatrics moving forward and identify strengths of virtual care and areas requiring improvement.

Moving towards a hybrid model of virtual and in-person care

Many sources identified telephone and video visits are likely to be integrated with in-person care moving forward after the pandemic, as a part of a blended model [5, 14, 15]. However, the use of eConsults has not been as widely adopted, despite the circumstances of the pandemic. Our responses suggest this may be related to the inherent process of eConsults. A consultant’s involvement in a patient’s care through eConsults is somewhat removed, as their recommendations are completed through the family doctor, without any direct patient contact. As such, these patients are not adopted into the consultant’s practice or followed-up upon. Although an identified facilitator of eConsults is that they can be completed efficiently, geriatrics care physicians must have adequate time to be able to serve this separate population of patient referrals, when they already have a long waitlist of patients waiting to see them, like many other specialties [16].

Older patients receiving virtual care during the pandemic have also expressed a preference for a blended model of in-person care and telephone or video visits but rely on physicians for guidance on its integration [5], which has also been identified as a professional responsibility for physicians by the Canadian Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario, the regulatory body for physicians in Ontario, Canada [17]. Our results can provide guidance on suitability of care within the scope of providing specialised geriatric services. Given the detailed and involved nature of comprehensive geriatric assessments, a concern towards the adequacy and accuracy of virtual care has previously been raised [5]. Our results specify incomplete assessments due to the absence of a complete physical exam and cognitive testing- traditional components crucial to a physician’s evaluation of a patient, as the main perceived limitations of virtual care. However, our results represent the perspective of physicians who newly implemented virtual care to their geriatric practice. A recent systematic review found videoconferencing cognitive assessments has good reliability and accuracy, when compared to in-person assessments [18]. Additionally, practical guidance on performing a virtual neurological exam now exist [19]. Yet, some physical exam manoeuvres are not feasible in the virtual format, and therefore, geriatric care physicians must recognise when their assessments are limited and identify patients who would benefit from further in-person assessment.

Virtual care serving a purpose in specialised geriatric care

Geriatric care physicians responding to our survey identified various roles for telemedicine in their clinical practice, which extend beyond the pandemic setting. Other studies completed on virtual care during the COVID-19 pandemic emphasised the importance of obtaining collateral information to guide clinical decision making [5, 18, 20], and our study provides clarity that specifically, the telephone best serves this purpose. Both telephone and video conferencing were felt to be suitable for follow-up visits. Additionally, all telemedicine tools can be used to efficiently improve access to geriatric care, as highlighted during the pandemic when in-person care was not permitted or discouraged, and also in relation to specialist wait times, and geographical or physical barriers experienced by patients as supported by previous literature evaluating the use of telemedicine prior to the pandemic [21, 22].

Despite the limitations of telemedicine, our study highlights its benefits within geriatric care. Improved accessibility of care was a main benefit of virtual care, similar to previous reports [22, 23], which was apparent prior to the pandemic, particularly for rural communities. Given the current deficit of geriatricians serving the older adult population in Ontario, Canada [24], the benefits of improved time efficiency offered by telemedicine can potentially help support long wait-times to accessing specialised geriatric services. Other benefits such as video conferencing allowing for some components of a physical examination were made in comparison to telephone visits in the context of the pandemic. Although not explicitly identified as a purpose of virtual care, we interpret that the benefits identified in our survey highlight aspects of virtual care that allow it to be complimentary to a geriatric assessment. For instance, telephone calls preceding an in-person appointment can assist in gathering collateral history, or a videoconferencing visit may allow the geriatrician to observe the home environment, without necessitating a home visit.

Identifying areas of improvement to overcome barriers of telemedicine

Importantly, our study identifies barriers of video visits, which highlights key areas requiring further program development and funding to help overcome challenges if a hybrid model of virtual and in-person care is to remain successfully in the future. Many barriers identified by geriatric care physicians, such as difficulty with using technology, sensory impairments and the need for on-demand help, have similarly been identified by older adults using video visits during the COVID-19 pandemic [25–27]. While videoconferencing offers unique benefits, it requires mutual access to and capability to use video-based technology. Currently, the Ontario Telemedicine Network supports communities with clinics equipped with videoconferencing tools to support telemedicine appointments where the specialist is located remotely. However, we encourage the development of programs to help older adults access and gain comfort using videoconferencing technology at home. The implementation of affordable and reliable broadband internet should be made available across hospitals [28] and different geographies, particularly in rural and remote communities, as suggested by others [14, 29]. Given the challenges of accessing videoconferencing visits for older adults who are frail, lack of caregiver support, require interpretation services or are racial and ethnic minorities [26, 30], we propose that ‘telemedicine support’ should be integrated into the scope of services provided by our publicly funded home care services. This is crucial to minimise the risk of exacerbating further health disparities, should a movement towards a hybrid model of in-person and virtual care become the norm. Such programs could allow support persons (e.g. personal support workers, nurses), to enter a patient’s residence with a video and internet-capable device and provide technological support for a medical encounter. Additional assistance could be provided for checking vitals, doing physical examinations, or cognitive testing. A previous study showed congruency between cognitive testing scores evaluated through video conferencing as compared to in person assessment; however, this involved the presence of a clinic nurse assisting the patient in the videoconference [31]. Ultimately, it is important that such a program be publicly funded and accessible to older adults living in both urban and rural areas, due to the multifaceted factors that undermine barriers to accessing healthcare, such as social and physical frailty, financial insecurity, or poor digital literacy.

Institutional barriers against using telemedicine are unique to each clinician’s practice location. Heyworth et al., demonstrated the Veterans Affairs’ compensation to institutions for video visits is three-times more than telephone visits. This may therefore bias institutions to incentivise or support video visits over telephone visits, despite other barriers or patient and provider preferences [32]. Similarly, the availability of telemedicine resources provided by an institution was identified as an important facilitator in another Canadian study evaluating the use of virtual care for older adults [33]. As virtual care becomes a routine aspect of clinical care, funding should reflect evidence-based practices, which are most appropriate, accessible, and safe for our older patients.

Study limitations

We acknowledge the potential limitations of using an online survey to solicit responses, however, strengths of this methodology include participatory advantages in light of increased clinical demands during the pandemic; an online survey was unobtrusive and less burdensome than traditional in-person methods. Additionally, the anonymised nature of online surveys may promote honest disclosure of participant perspectives [34]. The richness of our data may have been limited by our inability to ask follow-up questions, as permitted in open-ended interviews [35]. Additionally, most of our participants were geriatricians, who limits the generalisability of our results to care of the elderly physicians and those providing care in long-term care homes and should be taken into consideration by readers. Due to the unique aspect of clinical care provided in long-term care homes, with patients who are often more medically complex with functional impairment, the use of telemedicine in this setting requires further research. Lastly, we did not explore the perspectives of other key stakeholders, such as patients and caregivers.

Conclusions

In conclusion, virtual care, delivered through the telephone, videoconferencing and eConsults, each serve a specific purpose within geriatric care, such as providing follow-up care or increasing accessibility for those living in remote areas. However, barriers such as limited access to or unfamiliarity with technology can prohibit older adults from receiving virtual care, which can further exacerbate healthcare inequities. This should be a main area of focus in advancing the field of virtual care in geriatrics. Physicians must be cognizant of the limitations of virtual care and determine the appropriateness of when it can be used safely. Further research is required to identify additional strategies to improve the quality of and access to virtual care within geriatrics.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to have received funding for this project, the ‘Dr. Christopher Patterson Resident Research Grant in Senior’s Care Award’, through the Division of Geriatrics, Department of Medicine at McMaster University. We also thank Drs. Sharon Marr, Joye St. Onge, and Barbara Liu, as well as the Canadian Geriatrics Society, for their support in disseminating our survey.

Declaration of Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare regarding any commercial interests or personal interests in competing companies.

Declaration of Sources of Funding

This project was funded by the ‘Dr. Christopher Patterson Resident Research Grant in Senior’s Care Award’, through the Division of Geriatrics, Department of Medicine at McMaster University. The funders did not have a role in the study design, data analysis or interpretation, preparation, review, and approval of the final manuscript.

Comments