-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jagadish K Chhetri, Shanshan Mei, Chaodong Wang, Piu Chan, New horizons in Parkinson’s disease in older populations, Age and Ageing, Volume 52, Issue 10, October 2023, afad186, https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afad186

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder after Alzheimer’s disease. Ageing is considered to be the greatest risk factor for PD, with a complex interplay between genetics and the environment. With population ageing, the prevalence of PD is expected to escalate worldwide; thus, it is of utmost importance to reduce the burden of PD. To date, there are no therapies to cure the disease, and current treatment strategies focus on the management of symptoms. Older adults often have multiple chronic diseases and geriatric syndromes, which further complicates the management of PD. Healthcare systems and care models necessary to address the broad needs of older PD patients are largely unavailable. In this New Horizon article, we discuss various aspects of PD from an ageing perspective, including disease management. We highlight recent advancements in PD therapies and discuss new care models with the potential to improve patient’s quality of life.

Key Points

Ageing is a major risk factor for the development of Parkinson’s disease.

New concepts consider Parkinson’s disease as a multisystem disorder and ageing as the primary cause of clinical heterogeneity.

Patient-centred, individualised integrated care models are needed to meet the diverse care needs of older Parkinson’s disease patients.

Emerging therapies show great potential for symptomatic treatment of Parkinson’s disease.

Research on Parkinson’s disease should prioritise older adults, including inclusion in clinical trials.

Background

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is one of the most common neurodegenerative diseases, particularly affecting older adults [1]. The prevalence of PD is known to increase with age [2], and as such, old age is now recognised as a major risk factor for PD [3]. Ageing is considered a principal cause of heterogeneity in the clinical manifestations of PD, particularly for non-motor symptoms [3]. PD imposes a great burden on the healthcare system, patients and families. In particular, already vulnerable older adults are largely affected by a myriad of negative consequences of this disease. In this article,we discuss the various aspects of PD with a focus on ageing and older populations.

Ageing and PD

The global burden of PD has more than doubled from 2.5 million in 1990 to over 6 million in 2016, mainly as a result of population ageing, with the potential contribution from a few other factors [4]. Globally, the largest number of PD patients are aged over 65 years (prevalence approximately 1%) with prevalence increasing with age (4–5% by the age of 85 years) [5]. PD caused over 3 million disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) and 200 000 deaths in 2016 [4]. A recent study estimated the overall cost of managing PD in the USA to be over $79 billion by 2037 [6].

The association between ageing, neurodegeneration and PD has been well-established [3]. The combined effects of ageing such as cellular damage, failure of compensatory mechanisms and reduced physiological reserve, may lead to multisystem involvement and the rapid clinical progression of PD [3]. Geriatric syndromes, multimorbidity and polypharmacy are common in older adults, which complicates the management of PD. The lack of suitable drugs with minimal adverse effects in older patients is another challenge in the management of PD. Furthermore, healthcare systems and care models necessary to address the broad needs of older PD patients are largely unavailable.

Clinical presentation and diagnosis of PD in older adults

Clinical presentation

In general, the classical cardinal motor features of idiopathic PD are bradykinesia, rest tremor, rigidity, and postural and gait instability [7], which tend to worsen along with the progression of PD. Non-tremor (rigid-akinetic) dominant PD may be largely seen in late-onset PD (>70 years), featuring more complex motor deficits, postural and gait disturbance, and less susceptibility to levodopa-induced dyskinesias [8]. Clinicians face vast challenges in managing the complex issues that arise in older PD patients, such as treatment-resistant motor symptoms, freezing of gait, severe postural instability, falls, speech impairment and dysphagia [7].

Non-motor symptoms, including olfactory dysfunction, psychiatric symptoms, cognitive impairment and autonomic dysfunctions such as chronic constipation, incontinence and symptomatic orthostatic hypotension also exacerbate with the progression of PD. Severe autonomic and cognitive dysfunctions, including dementia, are more common in older patients with PD [9–11]. Patients experiencing these symptoms are often care-dependent, may need to be institutionalised, and are at high risk of mortality. Treatment-resistant non-motor features are major causes of functional decline and poor quality of life (QoL) in older PD patients [12].

Diagnostic considerations

In general clinical practice, the diagnosis of PD is based on neurological examinations and a comprehensive medical history of the patient. The diagnostic criteria of the Movement Disorder Society [13] and the UK Parkinson’s Disease Society Brain Bank clinical diagnostic criteria for PD [14] are widely used. Strategies to identify novel markers, such as from neuroimaging, pathology and genetics are being explored for early diagnosis of PD [15]. Considering the majority of PD patients are older individuals, with conditions such as cervical and lumbar disc diseases, frailty, arthritis, essential tremor, dementia or cardiovascular diseases, misdiagnosis is frequent [16]. While diagnosing older patients, it is crucial to obtain a detailed history of medications, as many common medications in this age group have extrapyramidal side effects (e.g. neuroleptics) and may also cause orthostatic hypotension (e.g. antidepressants). Suspected cases should be evaluated by movement disorder specialists to prevent misdiagnosis.

New ways of thinking about the phenotype of the disease

Considering the widespread deposition of α-synuclein and clinical heterogeneity, PD is no longer viewed as a disease solely affecting motor functions but rather as a chronic multisystem disorder [17]. The profound effect of levodopa or deep brain stimulation (DBS) therapy on motor symptoms has shifted the focus to non-motor symptoms, which significantly impact QoL in PD patients, particularly those who are older [9]. As a result, new concepts of non-motor phenotype with multiple subtypes (cognitive, apathy, depression/anxiety, sleep, pain, fatigue and autonomic) have been proposed [18]. This approach could be useful in designing targeted intervention trials or genetic studies for certain non-motor subtypes. Outcomes of such trials would add great value in understanding the natural history of PD and more importantly, play a vital role in reducing the burden of disability associated with non-motor symptoms. Correlating with the clinical subtyping concept in PD, it is argued that PD should be considered a dysfunctional multineurotransmitter pathway-driven syndrome rather than a mere dopaminergic motor disease [19]. These new concepts acknowledge the complexity and heterogeneity of PD.

Adverse events associated with PD in older patients

Older adults with PD may present with several adverse events such as falls and fractures, frailty, and cognitive impairment including delirium and dementia [20]. Late-stage PD patients with motor deficits (e.g. freezing of gait, motor fluctuations) and cognitive decline are at increased risk of falls and related fractures, while fractures from falls were found to be associated with increased mortality [21], making it important to assess falls in PD patients. Frailty, a state of increased vulnerability to stressors, is common among older adults [22], with almost 38% of individuals with PD found to be frail in a recent meta-analysis [23]. Given the higher rate of adverse events associated with frailty, including dependency, hospitalisation and mortality [22, 24], great care should be given to managing frail individuals with PD.

Bladder symptoms and constipation are also common in older PD patients. For bladder symptoms, patients are typically advised on fluid intake and habit training, while bladder training therapy was found to be useful to some extent [25]. Interestingly, a recent randomized controlled trial (RCT) showed transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation therapy to have some beneficial effects in treating bladder dysfunction in PD [26]. Similarly, constipation is a major factor associated with poor QoL in PD patients, which worsens with age. Patients are generally advised to follow a high-fibre diet and adequate fluid intake. Dietary interventions with probiotics and prebiotics have been found to significantly alleviate constipation symptoms in PD patients [27–29].

There is a high risk of dementia in patients with PD [10, 11]. PD patients with dementia and prolonged hospitalisation (due to severe aspiration pneumonia or fall-related fractures) are also more likely to present with neuropsychiatric symptoms such as delirium. Delirium in PD patients is associated with greater negative outcomes than in non-PD patients, is often less documented and is complex to manage [30]. Overall, these neurological symptoms pose a great risk of disability, care dependency and institutionalisation in older PD patients. Management of these complications and adverse events in PD patients requires an experienced multidisciplinary team.

Pharmacological management of PD in older patients

Motor symptoms management

It is necessary to select drugs with better efficacy and fewer adverse reactions for treating older patients. Levodopa is considered to be the drug of choice for monotherapy in older PD patients, as it has more positive effects on motor symptoms and milder adverse effects. Non-ergot dopamine agonists (DAs) are well-tolerated and without prohibitive adverse effects in less than half of older PD patients [31]. However, it is recommended that DAs use be approached with caution in patients with cognitive impairment, orthostatic hypotension, hallucinations and excessive daytime sleepiness [32]. Catechol-o-methyl-transferase (COMT) inhibitors and monoamine oxidase-B (MAO-B) inhibitors are good alternatives when adjunctive therapy is needed, but evidence in older populations is limited. Anticholinergic agents and amantadine have a high risk of adverse effects such as delirium, hallucinations and falls, which usually outweigh their benefits, so their use is limited in older patients [33, 34]. Since older patients have reduced renal and hepatic clearances and increased susceptibility to adverse effects, lower initial doses and slow titration of dopaminergic medicine guided by clinical response is generally needed [31].

Additionally, a wide range of comorbidities in older patients, as well as neurological and non-neurological symptoms, may result in the overuse of medications (including potentially inappropriate medication). Conversely, concerns of side effects may lead to the underuse of anti-Parkinsonian medication in older patients, exacerbating motor symptoms and disabilities, leading to worse QoL and short life expectancy. Hence, clinicians involved in the treatment of older patients should prioritise simplifying drug regimens, reducing adverse/toxic drug interactions and improving treatment adherence among older PD patients. In Table 1 we outline the best pharmacological approaches for managing older PD patients.

Therapies for the management of motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease older patients [33–39]

| . | Levodopa . | DAs . | MAO-B inhibitors . | Amantadine . | Anticholinergic agents . | COMT inhibitors . | Apomorphine infusion . | LCIG . | DBS . | Ablation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Options | Levodopa, carbidopa/levodopa, levodopa/benserazide | Bromocriptine mesylate, piribedil*, pramipexole, ropinirole, rotigotine | Rasagiline, safinaminde | Amantadine | Benztropine, trihexyphenidyl | Entacapone, opicapone | Apomorphine prn injection, apomorphine continuous infusion | Levodopa carbidopa intestinal gel | STN-DBS GPi-DBS Vim-DBS | Pallidotomy, thalamotomy, subthalamotomy, MRgFUS |

| Invasive | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| Efficacy | +++ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ (for tremor) | + (prolongs levodopa half-life) | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++ (for unilateral symptoms) |

| Motor fluctuations | +++ (monotherapy, increase dose or frequency) | ++ (adjunct) | + (adjunct) | + (adjunct) | − | ++ (adjunct) | +++ (adjunct when oral therapies fail) | +++ (monotherapy when oral therapies fail) | +++ (adjunct when oral therapies fail) | ++ (resistant tremor) |

| Dyskinesia | − (reduce dose) | − (reduce dose) | − (reduce dose) | ++ | − | − (reduce dose) | + (may be useful as CDD) | + (may be useful as CDD) | +++ | + |

| Drawbacks OH Cognitive impairment Psychosis Others | + − + Motor complication | ++ ++ ++ ICD, EDS, DAWS, sleep attacks, pedal oedema, dyskinesia | − + + Hypertension, caution required with SSRIs and SNRIs, dietary tyramine | − + ++ Pedal oedema, livedo reticularis | − +++ +++ Glaucoma | − − + Exacerbates levodopa side effects | ++ − ++ Nausea, skin nodules, skin discolouration | + − + PEG-J tube insertion, maintenance, set up by carer | − + ++ Patient selection (<75 years, exclude: psychosis, dementia, psychiatric disease) | − − − − |

| . | Levodopa . | DAs . | MAO-B inhibitors . | Amantadine . | Anticholinergic agents . | COMT inhibitors . | Apomorphine infusion . | LCIG . | DBS . | Ablation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Options | Levodopa, carbidopa/levodopa, levodopa/benserazide | Bromocriptine mesylate, piribedil*, pramipexole, ropinirole, rotigotine | Rasagiline, safinaminde | Amantadine | Benztropine, trihexyphenidyl | Entacapone, opicapone | Apomorphine prn injection, apomorphine continuous infusion | Levodopa carbidopa intestinal gel | STN-DBS GPi-DBS Vim-DBS | Pallidotomy, thalamotomy, subthalamotomy, MRgFUS |

| Invasive | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| Efficacy | +++ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ (for tremor) | + (prolongs levodopa half-life) | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++ (for unilateral symptoms) |

| Motor fluctuations | +++ (monotherapy, increase dose or frequency) | ++ (adjunct) | + (adjunct) | + (adjunct) | − | ++ (adjunct) | +++ (adjunct when oral therapies fail) | +++ (monotherapy when oral therapies fail) | +++ (adjunct when oral therapies fail) | ++ (resistant tremor) |

| Dyskinesia | − (reduce dose) | − (reduce dose) | − (reduce dose) | ++ | − | − (reduce dose) | + (may be useful as CDD) | + (may be useful as CDD) | +++ | + |

| Drawbacks OH Cognitive impairment Psychosis Others | + − + Motor complication | ++ ++ ++ ICD, EDS, DAWS, sleep attacks, pedal oedema, dyskinesia | − + + Hypertension, caution required with SSRIs and SNRIs, dietary tyramine | − + ++ Pedal oedema, livedo reticularis | − +++ +++ Glaucoma | − − + Exacerbates levodopa side effects | ++ − ++ Nausea, skin nodules, skin discolouration | + − + PEG-J tube insertion, maintenance, set up by carer | − + ++ Patient selection (<75 years, exclude: psychosis, dementia, psychiatric disease) | − − − − |

DAs, dopamine agonists; MAO-B, monoamine oxidase type B; COMT, catechol-O-methyl transferase; LCIG, levodopa carbidopa intestinal gel; DBS, deep brain stimulation; MRgFUS, magnetic resonance guided focused ultrasound; STN, subthalamic nucleus; GPi, globus pallidus interna; Vim, ventral intermedius; CDD, continuous drug delivery; DAWS, dopamine agonist withdrawal syndrome; EDS, excessive daytime sleepiness; OH, orthostatic hypotension; PEG-J, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy with jejunal extension; SNRI, serotonin noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Efficacy: +++ definitely good candidate, ++ probable good candidate, + possible candidate, − not a candidate.

Drawbacks: +++ considered as an absolute contraindication; ++ considered as sufficient contraindication; + considered as potential contraindication; − not a contraindication.

*Not licensed in the UK

Therapies for the management of motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease older patients [33–39]

| . | Levodopa . | DAs . | MAO-B inhibitors . | Amantadine . | Anticholinergic agents . | COMT inhibitors . | Apomorphine infusion . | LCIG . | DBS . | Ablation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Options | Levodopa, carbidopa/levodopa, levodopa/benserazide | Bromocriptine mesylate, piribedil*, pramipexole, ropinirole, rotigotine | Rasagiline, safinaminde | Amantadine | Benztropine, trihexyphenidyl | Entacapone, opicapone | Apomorphine prn injection, apomorphine continuous infusion | Levodopa carbidopa intestinal gel | STN-DBS GPi-DBS Vim-DBS | Pallidotomy, thalamotomy, subthalamotomy, MRgFUS |

| Invasive | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| Efficacy | +++ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ (for tremor) | + (prolongs levodopa half-life) | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++ (for unilateral symptoms) |

| Motor fluctuations | +++ (monotherapy, increase dose or frequency) | ++ (adjunct) | + (adjunct) | + (adjunct) | − | ++ (adjunct) | +++ (adjunct when oral therapies fail) | +++ (monotherapy when oral therapies fail) | +++ (adjunct when oral therapies fail) | ++ (resistant tremor) |

| Dyskinesia | − (reduce dose) | − (reduce dose) | − (reduce dose) | ++ | − | − (reduce dose) | + (may be useful as CDD) | + (may be useful as CDD) | +++ | + |

| Drawbacks OH Cognitive impairment Psychosis Others | + − + Motor complication | ++ ++ ++ ICD, EDS, DAWS, sleep attacks, pedal oedema, dyskinesia | − + + Hypertension, caution required with SSRIs and SNRIs, dietary tyramine | − + ++ Pedal oedema, livedo reticularis | − +++ +++ Glaucoma | − − + Exacerbates levodopa side effects | ++ − ++ Nausea, skin nodules, skin discolouration | + − + PEG-J tube insertion, maintenance, set up by carer | − + ++ Patient selection (<75 years, exclude: psychosis, dementia, psychiatric disease) | − − − − |

| . | Levodopa . | DAs . | MAO-B inhibitors . | Amantadine . | Anticholinergic agents . | COMT inhibitors . | Apomorphine infusion . | LCIG . | DBS . | Ablation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Options | Levodopa, carbidopa/levodopa, levodopa/benserazide | Bromocriptine mesylate, piribedil*, pramipexole, ropinirole, rotigotine | Rasagiline, safinaminde | Amantadine | Benztropine, trihexyphenidyl | Entacapone, opicapone | Apomorphine prn injection, apomorphine continuous infusion | Levodopa carbidopa intestinal gel | STN-DBS GPi-DBS Vim-DBS | Pallidotomy, thalamotomy, subthalamotomy, MRgFUS |

| Invasive | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| Efficacy | +++ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ (for tremor) | + (prolongs levodopa half-life) | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++ (for unilateral symptoms) |

| Motor fluctuations | +++ (monotherapy, increase dose or frequency) | ++ (adjunct) | + (adjunct) | + (adjunct) | − | ++ (adjunct) | +++ (adjunct when oral therapies fail) | +++ (monotherapy when oral therapies fail) | +++ (adjunct when oral therapies fail) | ++ (resistant tremor) |

| Dyskinesia | − (reduce dose) | − (reduce dose) | − (reduce dose) | ++ | − | − (reduce dose) | + (may be useful as CDD) | + (may be useful as CDD) | +++ | + |

| Drawbacks OH Cognitive impairment Psychosis Others | + − + Motor complication | ++ ++ ++ ICD, EDS, DAWS, sleep attacks, pedal oedema, dyskinesia | − + + Hypertension, caution required with SSRIs and SNRIs, dietary tyramine | − + ++ Pedal oedema, livedo reticularis | − +++ +++ Glaucoma | − − + Exacerbates levodopa side effects | ++ − ++ Nausea, skin nodules, skin discolouration | + − + PEG-J tube insertion, maintenance, set up by carer | − + ++ Patient selection (<75 years, exclude: psychosis, dementia, psychiatric disease) | − − − − |

DAs, dopamine agonists; MAO-B, monoamine oxidase type B; COMT, catechol-O-methyl transferase; LCIG, levodopa carbidopa intestinal gel; DBS, deep brain stimulation; MRgFUS, magnetic resonance guided focused ultrasound; STN, subthalamic nucleus; GPi, globus pallidus interna; Vim, ventral intermedius; CDD, continuous drug delivery; DAWS, dopamine agonist withdrawal syndrome; EDS, excessive daytime sleepiness; OH, orthostatic hypotension; PEG-J, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy with jejunal extension; SNRI, serotonin noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Efficacy: +++ definitely good candidate, ++ probable good candidate, + possible candidate, − not a candidate.

Drawbacks: +++ considered as an absolute contraindication; ++ considered as sufficient contraindication; + considered as potential contraindication; − not a contraindication.

*Not licensed in the UK

Non-motor symptoms management

All PD patients should have postural blood pressure measurements before initiating any new treatments. In treating sleep disturbances, benzodiazepines should generally be avoided in older patients [39]; melatonin may be preferable due to milder adverse effects [40]. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are most commonly used in clinical practice to manage depression [41]. Drugs such as tricyclic antidepressants and paroxetine, which are high-potency anticholinergic drugs [42], may cause some adverse behavioural effects such as confusion, memory problems, hallucinations and restlessness [39, 43].

Cognitive decline and eventual dementia have been reported to occur in approximately 40% (at 10 years) to 80% (at 20 years) of PD patients [10, 11]. Certain PD medications can aggravate cognitive impairment and when there are problematic neuropsychiatric symptoms, it is recommended to reduce or withdraw dopaminergic medications, beginning with the least effective agents. Anticholinergics should be reduced first, followed by amantadine, MAO-B inhibitors, dopamine agonists, COMT inhibitors and lastly, levodopa [44].

Psychosis is a well-established feature of late PD, and the first step in managing psychosis is to eliminate the causes or triggers, such as infection, dehydration or electrolyte imbalance, and reduce exacerbating medications [45]. Non-pharmacological strategies should be implemented initially; however, if symptoms persist and there is a risk of harm, an atypical antipsychotic may be used [44, 45] (Table 2).

| Symptoms . | Options . | Efficacy . | Adverse events . |

|---|---|---|---|

| EDS | Adjust anti-Parkinsonism medicine regime Modafinil Methylphenidate | + ++ ++ | – Headache, nausea, nervousness, insomnia Headache, nausea, insomnia |

| Caffeine | + | Insomnia | |

| RBD | Clonazepam Melatonin | ++ ++ | Falls – |

| OH | Midodrine Droxidopa* Fludrocortisone | ++ + +++ | SH, paresthesia, dysurea Neuroleptic malignant syndrome, agranulocytosis, supine hypertension SH, oedema |

| Pyridostigmine | + | SH, dizziness, headache, nausea | |

| Depression | SSRIs SNRIs TCAs DAs | +++ +++ ++ +++ | Motor symptom aggravation Motor symptom aggravation Anticholinergic reactions, arrhythmia OH, cognitive impairment, psychosis |

| Apathy | DAs | ++ | OH, cognitive impairment, psychosis |

| Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors | +++ | Worsening of tremor | |

| Memantine | + | Drowsiness,dizziness, constipation | |

| Psychosis | Quetiapine | ++ | Sedation, OH and falls |

| Clozapine | +++ | Agranulocytosis, sedation, OH and falls | |

| Pimavanserin | +++ | QT prolongation, paradoxical worsening of PD symptoms | |

| Dementia | Reduce anti-Parkinsonism medicine | ++ | Motor symptom aggravation |

| Acteylcholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil/rivastigmine) | ++ | Tremor, nausea, vomiting, syncope, bradycardia, fall | |

| Memantine (second line) | + | Drowsiness,dizziness, constipation | |

| Drooling | Glycopyrronium bromide Botulinum toxin A | ++ ++ | Glaucoma, urinary retention, psychosis Dysphagia |

| Botulinum toxin B | ++ | Dysphagia | |

| Atropine eye drop | + | Tachycardia, anaphylaxis | |

| Ipratropium inhaler | + | Nausea, diarrhoea, cough | |

| Constipation | Lubiproston* | ++ | Nausea, diarrhoea, dyspnea |

| Probiotics and prebiotic fibre | +++ | – | |

| Macrogol | ++ | Nausea, diarrhoea | |

| Urinary incontinence | Solifenacin | + | Constipation, dyspepsia, dizziness, headache |

| Mirabegron | + | Tachycardia,urinary tract infection | |

| Trospium | ++ | Constipation, nausea | |

| Erectile dysfunction | Sildenafil | +++ | OH |

| Symptoms . | Options . | Efficacy . | Adverse events . |

|---|---|---|---|

| EDS | Adjust anti-Parkinsonism medicine regime Modafinil Methylphenidate | + ++ ++ | – Headache, nausea, nervousness, insomnia Headache, nausea, insomnia |

| Caffeine | + | Insomnia | |

| RBD | Clonazepam Melatonin | ++ ++ | Falls – |

| OH | Midodrine Droxidopa* Fludrocortisone | ++ + +++ | SH, paresthesia, dysurea Neuroleptic malignant syndrome, agranulocytosis, supine hypertension SH, oedema |

| Pyridostigmine | + | SH, dizziness, headache, nausea | |

| Depression | SSRIs SNRIs TCAs DAs | +++ +++ ++ +++ | Motor symptom aggravation Motor symptom aggravation Anticholinergic reactions, arrhythmia OH, cognitive impairment, psychosis |

| Apathy | DAs | ++ | OH, cognitive impairment, psychosis |

| Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors | +++ | Worsening of tremor | |

| Memantine | + | Drowsiness,dizziness, constipation | |

| Psychosis | Quetiapine | ++ | Sedation, OH and falls |

| Clozapine | +++ | Agranulocytosis, sedation, OH and falls | |

| Pimavanserin | +++ | QT prolongation, paradoxical worsening of PD symptoms | |

| Dementia | Reduce anti-Parkinsonism medicine | ++ | Motor symptom aggravation |

| Acteylcholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil/rivastigmine) | ++ | Tremor, nausea, vomiting, syncope, bradycardia, fall | |

| Memantine (second line) | + | Drowsiness,dizziness, constipation | |

| Drooling | Glycopyrronium bromide Botulinum toxin A | ++ ++ | Glaucoma, urinary retention, psychosis Dysphagia |

| Botulinum toxin B | ++ | Dysphagia | |

| Atropine eye drop | + | Tachycardia, anaphylaxis | |

| Ipratropium inhaler | + | Nausea, diarrhoea, cough | |

| Constipation | Lubiproston* | ++ | Nausea, diarrhoea, dyspnea |

| Probiotics and prebiotic fibre | +++ | – | |

| Macrogol | ++ | Nausea, diarrhoea | |

| Urinary incontinence | Solifenacin | + | Constipation, dyspepsia, dizziness, headache |

| Mirabegron | + | Tachycardia,urinary tract infection | |

| Trospium | ++ | Constipation, nausea | |

| Erectile dysfunction | Sildenafil | +++ | OH |

EDS, excessive daytime sleepiness; RBD, rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder; OH, orthostatic hypotension; SH, supine hypertension; SNRI, serotonin noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant; DAs, dopamine agonists; PD, Parkinson's disease.

Efficacy: +++ definitely good candidate, ++ probable good candidate, + possible candidate, − not a candidate.

*Not licensed in the UK

| Symptoms . | Options . | Efficacy . | Adverse events . |

|---|---|---|---|

| EDS | Adjust anti-Parkinsonism medicine regime Modafinil Methylphenidate | + ++ ++ | – Headache, nausea, nervousness, insomnia Headache, nausea, insomnia |

| Caffeine | + | Insomnia | |

| RBD | Clonazepam Melatonin | ++ ++ | Falls – |

| OH | Midodrine Droxidopa* Fludrocortisone | ++ + +++ | SH, paresthesia, dysurea Neuroleptic malignant syndrome, agranulocytosis, supine hypertension SH, oedema |

| Pyridostigmine | + | SH, dizziness, headache, nausea | |

| Depression | SSRIs SNRIs TCAs DAs | +++ +++ ++ +++ | Motor symptom aggravation Motor symptom aggravation Anticholinergic reactions, arrhythmia OH, cognitive impairment, psychosis |

| Apathy | DAs | ++ | OH, cognitive impairment, psychosis |

| Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors | +++ | Worsening of tremor | |

| Memantine | + | Drowsiness,dizziness, constipation | |

| Psychosis | Quetiapine | ++ | Sedation, OH and falls |

| Clozapine | +++ | Agranulocytosis, sedation, OH and falls | |

| Pimavanserin | +++ | QT prolongation, paradoxical worsening of PD symptoms | |

| Dementia | Reduce anti-Parkinsonism medicine | ++ | Motor symptom aggravation |

| Acteylcholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil/rivastigmine) | ++ | Tremor, nausea, vomiting, syncope, bradycardia, fall | |

| Memantine (second line) | + | Drowsiness,dizziness, constipation | |

| Drooling | Glycopyrronium bromide Botulinum toxin A | ++ ++ | Glaucoma, urinary retention, psychosis Dysphagia |

| Botulinum toxin B | ++ | Dysphagia | |

| Atropine eye drop | + | Tachycardia, anaphylaxis | |

| Ipratropium inhaler | + | Nausea, diarrhoea, cough | |

| Constipation | Lubiproston* | ++ | Nausea, diarrhoea, dyspnea |

| Probiotics and prebiotic fibre | +++ | – | |

| Macrogol | ++ | Nausea, diarrhoea | |

| Urinary incontinence | Solifenacin | + | Constipation, dyspepsia, dizziness, headache |

| Mirabegron | + | Tachycardia,urinary tract infection | |

| Trospium | ++ | Constipation, nausea | |

| Erectile dysfunction | Sildenafil | +++ | OH |

| Symptoms . | Options . | Efficacy . | Adverse events . |

|---|---|---|---|

| EDS | Adjust anti-Parkinsonism medicine regime Modafinil Methylphenidate | + ++ ++ | – Headache, nausea, nervousness, insomnia Headache, nausea, insomnia |

| Caffeine | + | Insomnia | |

| RBD | Clonazepam Melatonin | ++ ++ | Falls – |

| OH | Midodrine Droxidopa* Fludrocortisone | ++ + +++ | SH, paresthesia, dysurea Neuroleptic malignant syndrome, agranulocytosis, supine hypertension SH, oedema |

| Pyridostigmine | + | SH, dizziness, headache, nausea | |

| Depression | SSRIs SNRIs TCAs DAs | +++ +++ ++ +++ | Motor symptom aggravation Motor symptom aggravation Anticholinergic reactions, arrhythmia OH, cognitive impairment, psychosis |

| Apathy | DAs | ++ | OH, cognitive impairment, psychosis |

| Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors | +++ | Worsening of tremor | |

| Memantine | + | Drowsiness,dizziness, constipation | |

| Psychosis | Quetiapine | ++ | Sedation, OH and falls |

| Clozapine | +++ | Agranulocytosis, sedation, OH and falls | |

| Pimavanserin | +++ | QT prolongation, paradoxical worsening of PD symptoms | |

| Dementia | Reduce anti-Parkinsonism medicine | ++ | Motor symptom aggravation |

| Acteylcholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil/rivastigmine) | ++ | Tremor, nausea, vomiting, syncope, bradycardia, fall | |

| Memantine (second line) | + | Drowsiness,dizziness, constipation | |

| Drooling | Glycopyrronium bromide Botulinum toxin A | ++ ++ | Glaucoma, urinary retention, psychosis Dysphagia |

| Botulinum toxin B | ++ | Dysphagia | |

| Atropine eye drop | + | Tachycardia, anaphylaxis | |

| Ipratropium inhaler | + | Nausea, diarrhoea, cough | |

| Constipation | Lubiproston* | ++ | Nausea, diarrhoea, dyspnea |

| Probiotics and prebiotic fibre | +++ | – | |

| Macrogol | ++ | Nausea, diarrhoea | |

| Urinary incontinence | Solifenacin | + | Constipation, dyspepsia, dizziness, headache |

| Mirabegron | + | Tachycardia,urinary tract infection | |

| Trospium | ++ | Constipation, nausea | |

| Erectile dysfunction | Sildenafil | +++ | OH |

EDS, excessive daytime sleepiness; RBD, rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder; OH, orthostatic hypotension; SH, supine hypertension; SNRI, serotonin noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant; DAs, dopamine agonists; PD, Parkinson's disease.

Efficacy: +++ definitely good candidate, ++ probable good candidate, + possible candidate, − not a candidate.

*Not licensed in the UK

Advanced therapies

As PD progresses, most patients develop motor fluctuations, dyskinesia and ‘off’ time, which are difficult to manage with oral pharmacological therapy. These patients may benefit from one of the more advanced available treatments, including deep brain stimulation (DBS), continuous subcutaneous apomorphine infusion (CSAI) and levodopa-carbidopa intestinal gel (LCIG) infusion [37]. In general, patients who have a good levodopa response, are younger than 75 years and with good cognitive function are considered good candidates for all three device-aided therapies [37] (Table 1). However, the reason for the choice of age limit is unclear, given the lack of evidence. Brain ageing associated neuronal loss and brain atrophy in older patients may influence the outcome of DBS. There is a limited treatment timeframe for DBS due to specific motor and cognitive eligibility considerations, while CSAI and LCIG treatments may have a longer timeframe. Lesioning or ablative surgeries (LS) are other alternatives for older PD patients and have been considered reasonable solutions for patients with severe tremor or dyskinesia who are contraindicated for DBS [46]. Ablation can be performed using radiofrequency (RF), stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound (MRgFUS) and laser interstitial thermal therapy (LITT). The European Academy of Neurology and the European section of the Movement Disorder Society have recently published a guideline on initiating invasive therapies for PD [47].

Emerging therapies

Emerging therapies for PD are largely aimed at disease modification, targeting α-synuclein and its pathways, or genes and proteins, such as leucine-rich repeat kinase 2, parkin and glucocerebrosidase [48]. Despite considerable effort, there are currently no disease-modifying agents that have been shown to halt disease progression. Several agents targeting specific neuronal rescue pathways are also being tested. In addition, various emerging therapies have shown promising results for the symptomatic management of PD. We have listed some of the emerging pharmacological therapies (recently completed or ongoing clinical trials phase 2 and above) in Table 3.

| Treatment . | Mechanism . | Phase/clinical trial number . | Patients . | Outcomes/aims . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deferiprone | DMT, an iron-chelating agent | II/ NCT02655315 | Early-onset PD | No beneficial effects according to change in UPDRS |

| Exenatide | DMT, a glucagon-like peptide 1 agonist | III/ NCT04232969 | Preclinical modes of PD | Neuroprotective effects, improving off-medication motor scores |

| Tavadapon | DMT, a selective partial agonist of the dopamine D1 and D5 receptors | III, IV/ NCT04542499/ NCT04223193/ NCT04760769 | Early-onset PD, Late-stage PD | Activate the direct motor pathway and improve motor symptoms |

| Cinpanemab | DMT, a human-derived monoclonal antibody that binds to α-synuclein | III/ NCT03318523 | Early PD | No changes on clinical measures of disease progression and DaT-SPECT imaging |

| Prasinezumab | DMT, a human-derived monoclonal antibody that binds to α-synuclein | II/ NCT03100149 | Early PD | No meaningful effect on global or imaging measures of PD progression |

| UCB0599 | DMT, small-molecule inhibitor of α-synuclein misfolding | II/ NCT04658186 | Early PD | Aimed at slowing PD progression |

| Ambroxol | DMT, a metabolite of bromhexine | II/ NCT05287503 | PD with mutations of the glucocerebrosidase gene | Aimed at slowing PD progression by changing glucocerebrosidase enzyme activity and α-synuclein levels |

| BIIB122 | DMT, small-molecule kinase inhibitor | III/ NCT05418673 | Early PD with a specific genetic variant in their LRRK2 gene | Aimed at slowing PD progression |

| Pimavanserin | A selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor or serotonin/noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor | II, IV/ NCT03482882, NCT04292223 | Depressive symptoms in PD patients | Improvement of depressive symptoms |

| LY03003 | Cholinesterase inhibitor | III/ NCT04226248 | PD patients with a history of falls | Effective in preventing falls in PD |

| ABBV-951 | Continuous subcutaneous infusion of foslevodopa-foscarbidopa | III/ NCT04380142 | Advanced PD | Improved motor fluctuations |

| APL-130277 | Apomorphine sublingual film | III/ NCT02469090 | PD | Effective for off episodes in PD patients |

| Istradefylline | A selective adenosine A2A receptor antagonist | III/ NCT01968031 | Idiopathic PD | Effective for off episodes in PD patients |

| Nabilone | An analogue of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), partial agonist on both Cannabinoid 1 (CB1) and Cannabinoid 2 (CB2) receptors | II/ III/ NCT03769896, NCT03773796 | PD non-motor symptoms | Improvement in mood and sleep |

| SEP-363856 | Psychotropic agent with a unique, non-D2 receptor mechanism of action | IIb/ NCT02969369 | PD psychosis | Effective in phencyclidine (PCP)-induced hyperactivity, prepulse inhibition and PCP-induced deficits in social interaction |

| SAGE-718 | NMDA receptor modulator | II/ NCT04476017 | Cognitive impairment associated with PD | Aimed to improve cognitive, neuropsychiatric and motor symptoms |

| ANAVEX2–73 | Activates SIGMAR1 | II/ NCT03774459 | Cognitive impairment associated with PD | Cognitive improvement, reduce motor and non-motor symptoms |

| ENT-01 | Prevents the accumulation of α-synuclein in the nerves that line the gastrointestinal tract | II/ NCT03781791 | PD patients with constipation | Improve PD associated constipation |

| Ampreloxetine | A novel, selective, long-acting norepinephrine reuptake (NET) inhibitor | III/ NCT03750552 | Symptomatic neurogenic orthostatic hypotension | Aimed for improvement in Orthostatic Hypotension Symptom Assessment (OHSA) |

| Treatment . | Mechanism . | Phase/clinical trial number . | Patients . | Outcomes/aims . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deferiprone | DMT, an iron-chelating agent | II/ NCT02655315 | Early-onset PD | No beneficial effects according to change in UPDRS |

| Exenatide | DMT, a glucagon-like peptide 1 agonist | III/ NCT04232969 | Preclinical modes of PD | Neuroprotective effects, improving off-medication motor scores |

| Tavadapon | DMT, a selective partial agonist of the dopamine D1 and D5 receptors | III, IV/ NCT04542499/ NCT04223193/ NCT04760769 | Early-onset PD, Late-stage PD | Activate the direct motor pathway and improve motor symptoms |

| Cinpanemab | DMT, a human-derived monoclonal antibody that binds to α-synuclein | III/ NCT03318523 | Early PD | No changes on clinical measures of disease progression and DaT-SPECT imaging |

| Prasinezumab | DMT, a human-derived monoclonal antibody that binds to α-synuclein | II/ NCT03100149 | Early PD | No meaningful effect on global or imaging measures of PD progression |

| UCB0599 | DMT, small-molecule inhibitor of α-synuclein misfolding | II/ NCT04658186 | Early PD | Aimed at slowing PD progression |

| Ambroxol | DMT, a metabolite of bromhexine | II/ NCT05287503 | PD with mutations of the glucocerebrosidase gene | Aimed at slowing PD progression by changing glucocerebrosidase enzyme activity and α-synuclein levels |

| BIIB122 | DMT, small-molecule kinase inhibitor | III/ NCT05418673 | Early PD with a specific genetic variant in their LRRK2 gene | Aimed at slowing PD progression |

| Pimavanserin | A selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor or serotonin/noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor | II, IV/ NCT03482882, NCT04292223 | Depressive symptoms in PD patients | Improvement of depressive symptoms |

| LY03003 | Cholinesterase inhibitor | III/ NCT04226248 | PD patients with a history of falls | Effective in preventing falls in PD |

| ABBV-951 | Continuous subcutaneous infusion of foslevodopa-foscarbidopa | III/ NCT04380142 | Advanced PD | Improved motor fluctuations |

| APL-130277 | Apomorphine sublingual film | III/ NCT02469090 | PD | Effective for off episodes in PD patients |

| Istradefylline | A selective adenosine A2A receptor antagonist | III/ NCT01968031 | Idiopathic PD | Effective for off episodes in PD patients |

| Nabilone | An analogue of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), partial agonist on both Cannabinoid 1 (CB1) and Cannabinoid 2 (CB2) receptors | II/ III/ NCT03769896, NCT03773796 | PD non-motor symptoms | Improvement in mood and sleep |

| SEP-363856 | Psychotropic agent with a unique, non-D2 receptor mechanism of action | IIb/ NCT02969369 | PD psychosis | Effective in phencyclidine (PCP)-induced hyperactivity, prepulse inhibition and PCP-induced deficits in social interaction |

| SAGE-718 | NMDA receptor modulator | II/ NCT04476017 | Cognitive impairment associated with PD | Aimed to improve cognitive, neuropsychiatric and motor symptoms |

| ANAVEX2–73 | Activates SIGMAR1 | II/ NCT03774459 | Cognitive impairment associated with PD | Cognitive improvement, reduce motor and non-motor symptoms |

| ENT-01 | Prevents the accumulation of α-synuclein in the nerves that line the gastrointestinal tract | II/ NCT03781791 | PD patients with constipation | Improve PD associated constipation |

| Ampreloxetine | A novel, selective, long-acting norepinephrine reuptake (NET) inhibitor | III/ NCT03750552 | Symptomatic neurogenic orthostatic hypotension | Aimed for improvement in Orthostatic Hypotension Symptom Assessment (OHSA) |

PD, Parkinson’s disease; DMT, disease-modifying therapy; NMDA, N-methyl-d-aspartate; SIGMAR1, sigma-1 receptor; UPDRS, unified Parkinson's disease rating scale; DaT-SPECT, dopamine transporter single-photon emission computed tomography.

| Treatment . | Mechanism . | Phase/clinical trial number . | Patients . | Outcomes/aims . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deferiprone | DMT, an iron-chelating agent | II/ NCT02655315 | Early-onset PD | No beneficial effects according to change in UPDRS |

| Exenatide | DMT, a glucagon-like peptide 1 agonist | III/ NCT04232969 | Preclinical modes of PD | Neuroprotective effects, improving off-medication motor scores |

| Tavadapon | DMT, a selective partial agonist of the dopamine D1 and D5 receptors | III, IV/ NCT04542499/ NCT04223193/ NCT04760769 | Early-onset PD, Late-stage PD | Activate the direct motor pathway and improve motor symptoms |

| Cinpanemab | DMT, a human-derived monoclonal antibody that binds to α-synuclein | III/ NCT03318523 | Early PD | No changes on clinical measures of disease progression and DaT-SPECT imaging |

| Prasinezumab | DMT, a human-derived monoclonal antibody that binds to α-synuclein | II/ NCT03100149 | Early PD | No meaningful effect on global or imaging measures of PD progression |

| UCB0599 | DMT, small-molecule inhibitor of α-synuclein misfolding | II/ NCT04658186 | Early PD | Aimed at slowing PD progression |

| Ambroxol | DMT, a metabolite of bromhexine | II/ NCT05287503 | PD with mutations of the glucocerebrosidase gene | Aimed at slowing PD progression by changing glucocerebrosidase enzyme activity and α-synuclein levels |

| BIIB122 | DMT, small-molecule kinase inhibitor | III/ NCT05418673 | Early PD with a specific genetic variant in their LRRK2 gene | Aimed at slowing PD progression |

| Pimavanserin | A selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor or serotonin/noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor | II, IV/ NCT03482882, NCT04292223 | Depressive symptoms in PD patients | Improvement of depressive symptoms |

| LY03003 | Cholinesterase inhibitor | III/ NCT04226248 | PD patients with a history of falls | Effective in preventing falls in PD |

| ABBV-951 | Continuous subcutaneous infusion of foslevodopa-foscarbidopa | III/ NCT04380142 | Advanced PD | Improved motor fluctuations |

| APL-130277 | Apomorphine sublingual film | III/ NCT02469090 | PD | Effective for off episodes in PD patients |

| Istradefylline | A selective adenosine A2A receptor antagonist | III/ NCT01968031 | Idiopathic PD | Effective for off episodes in PD patients |

| Nabilone | An analogue of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), partial agonist on both Cannabinoid 1 (CB1) and Cannabinoid 2 (CB2) receptors | II/ III/ NCT03769896, NCT03773796 | PD non-motor symptoms | Improvement in mood and sleep |

| SEP-363856 | Psychotropic agent with a unique, non-D2 receptor mechanism of action | IIb/ NCT02969369 | PD psychosis | Effective in phencyclidine (PCP)-induced hyperactivity, prepulse inhibition and PCP-induced deficits in social interaction |

| SAGE-718 | NMDA receptor modulator | II/ NCT04476017 | Cognitive impairment associated with PD | Aimed to improve cognitive, neuropsychiatric and motor symptoms |

| ANAVEX2–73 | Activates SIGMAR1 | II/ NCT03774459 | Cognitive impairment associated with PD | Cognitive improvement, reduce motor and non-motor symptoms |

| ENT-01 | Prevents the accumulation of α-synuclein in the nerves that line the gastrointestinal tract | II/ NCT03781791 | PD patients with constipation | Improve PD associated constipation |

| Ampreloxetine | A novel, selective, long-acting norepinephrine reuptake (NET) inhibitor | III/ NCT03750552 | Symptomatic neurogenic orthostatic hypotension | Aimed for improvement in Orthostatic Hypotension Symptom Assessment (OHSA) |

| Treatment . | Mechanism . | Phase/clinical trial number . | Patients . | Outcomes/aims . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deferiprone | DMT, an iron-chelating agent | II/ NCT02655315 | Early-onset PD | No beneficial effects according to change in UPDRS |

| Exenatide | DMT, a glucagon-like peptide 1 agonist | III/ NCT04232969 | Preclinical modes of PD | Neuroprotective effects, improving off-medication motor scores |

| Tavadapon | DMT, a selective partial agonist of the dopamine D1 and D5 receptors | III, IV/ NCT04542499/ NCT04223193/ NCT04760769 | Early-onset PD, Late-stage PD | Activate the direct motor pathway and improve motor symptoms |

| Cinpanemab | DMT, a human-derived monoclonal antibody that binds to α-synuclein | III/ NCT03318523 | Early PD | No changes on clinical measures of disease progression and DaT-SPECT imaging |

| Prasinezumab | DMT, a human-derived monoclonal antibody that binds to α-synuclein | II/ NCT03100149 | Early PD | No meaningful effect on global or imaging measures of PD progression |

| UCB0599 | DMT, small-molecule inhibitor of α-synuclein misfolding | II/ NCT04658186 | Early PD | Aimed at slowing PD progression |

| Ambroxol | DMT, a metabolite of bromhexine | II/ NCT05287503 | PD with mutations of the glucocerebrosidase gene | Aimed at slowing PD progression by changing glucocerebrosidase enzyme activity and α-synuclein levels |

| BIIB122 | DMT, small-molecule kinase inhibitor | III/ NCT05418673 | Early PD with a specific genetic variant in their LRRK2 gene | Aimed at slowing PD progression |

| Pimavanserin | A selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor or serotonin/noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor | II, IV/ NCT03482882, NCT04292223 | Depressive symptoms in PD patients | Improvement of depressive symptoms |

| LY03003 | Cholinesterase inhibitor | III/ NCT04226248 | PD patients with a history of falls | Effective in preventing falls in PD |

| ABBV-951 | Continuous subcutaneous infusion of foslevodopa-foscarbidopa | III/ NCT04380142 | Advanced PD | Improved motor fluctuations |

| APL-130277 | Apomorphine sublingual film | III/ NCT02469090 | PD | Effective for off episodes in PD patients |

| Istradefylline | A selective adenosine A2A receptor antagonist | III/ NCT01968031 | Idiopathic PD | Effective for off episodes in PD patients |

| Nabilone | An analogue of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), partial agonist on both Cannabinoid 1 (CB1) and Cannabinoid 2 (CB2) receptors | II/ III/ NCT03769896, NCT03773796 | PD non-motor symptoms | Improvement in mood and sleep |

| SEP-363856 | Psychotropic agent with a unique, non-D2 receptor mechanism of action | IIb/ NCT02969369 | PD psychosis | Effective in phencyclidine (PCP)-induced hyperactivity, prepulse inhibition and PCP-induced deficits in social interaction |

| SAGE-718 | NMDA receptor modulator | II/ NCT04476017 | Cognitive impairment associated with PD | Aimed to improve cognitive, neuropsychiatric and motor symptoms |

| ANAVEX2–73 | Activates SIGMAR1 | II/ NCT03774459 | Cognitive impairment associated with PD | Cognitive improvement, reduce motor and non-motor symptoms |

| ENT-01 | Prevents the accumulation of α-synuclein in the nerves that line the gastrointestinal tract | II/ NCT03781791 | PD patients with constipation | Improve PD associated constipation |

| Ampreloxetine | A novel, selective, long-acting norepinephrine reuptake (NET) inhibitor | III/ NCT03750552 | Symptomatic neurogenic orthostatic hypotension | Aimed for improvement in Orthostatic Hypotension Symptom Assessment (OHSA) |

PD, Parkinson’s disease; DMT, disease-modifying therapy; NMDA, N-methyl-d-aspartate; SIGMAR1, sigma-1 receptor; UPDRS, unified Parkinson's disease rating scale; DaT-SPECT, dopamine transporter single-photon emission computed tomography.

Cell therapies or gene therapy are still experimental and are far from immediate clinical use. Adaptive DBS is an emerging invasive therapy that is able to auto-adjust stimulation using feedback from the brain itself [49]. This technique has greater clinical benefits for patients and reduces the neurostimulation battery costs. Recently, non-invasive and optogenetically inspired DBS methods have also been emerging [50, 51], which will drastically reduce the risk associated with traditional DBS surgery. Several other candidate therapies are being investigated, which have been well-described elsewhere [48, 52].

Non-pharmacological management of PD

Despite regular use of medication or surgery, a significant proportion of PD patients continue to experience several refractory motor or non-motor symptoms. These symptoms are even more prominent in the late stage of PD when the patients themselves are old and frail, and certain medications may not be suitable due to severe side effects. Older patients are generally not considered ideal candidates for surgical procedures, and many of these advanced treatments are extremely costly. At this stage, several non-pharmacological therapies may be implemented, including physiotherapy (sports and exercise), occupational and speech therapy, patient and family education, cognitive training, nutritional management and psychological support [46, 53]. It should be noted that much of the evidence for these therapies comes from studies that excluded relatively older patients. Nevertheless, physical activity and exercise have been found to improve gait difficulties and balance, and reduce the risk of falls in PD patients irrespective of age [41, 54]. The neuroprotective effect of exercise in PD is widely accepted [55, 56], but individual-tailored exercise may be needed to address the needs of each PD patient, as symptoms are heterogeneous, and many older patients are unable to perform the recommended exercises. A recent phase 2 RCT of high-intensity treadmill exercise showed slowing of motor impairment in new-onset PD [57]. Concomitantly, exercise therapy prescribed remotely was also found to attenuate off-state motor signs [58].

Occupational therapy may help PD patients maintain their activities of daily livings (ADLs) and adapt to their environment, thereby developing independence and a sense of empowerment in old age [54]. PD patients with speech impairment and dysphagia may benefit from speech and language therapy [54], reducing the risk of aspiration pneumonia. Cognitive therapies may also be beneficial for patients at risk of cognitive decline, although there is a lack of robust evidence on this topic [39]. A recent RCT has shown cognitive training to improve cognitive and affective functions in PD patients [59].

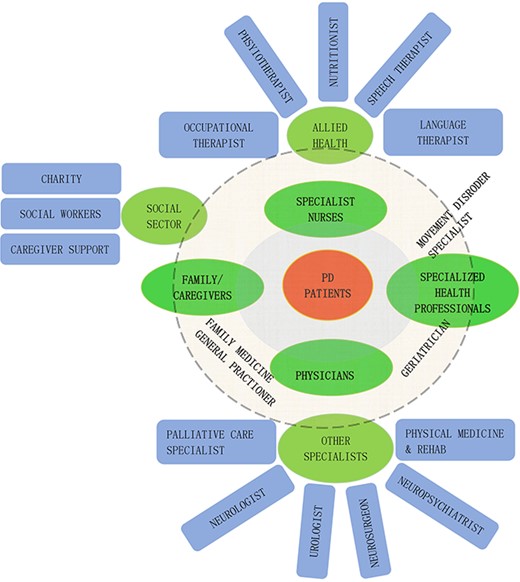

Special nutritional guidance may help older patients in maintaining protein redistribution to improve the efficacy of medications. Specialist advice on preventing weight loss or taking nutritional supplementation, such as vitamin D supplementation (potentially for preventing falls or osteoporosis) [53] or protein intake may be needed for older PD patients. PD is a complex disease with a myriad of symptoms, providing education and psychological support to the patients, their families and caregivers may help improve their understanding of the disease and its progression, and reduce mental stress. Managing PD in older adults is a complex process requiring multispecialty and multisector involvement (Figure 1).

A multi-disciplinary/multi-sector team involvement is needed to manage Parkinson’s disease in older adults.

New models of care for PD

PD patients have multifaceted care needs and delivering a person-centred comprehensive care requires a multispecialty (multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, integrated) approach. However, it has been argued that a hospital-based multispecialty care model is largely unsustainable [60]. A one-stop comprehensive health team is difficult to maintain in many parts of the world, because of the disparity in available resources. Concomitantly, studies have shown multidisciplinary care models to have a relatively small beneficial effect on QoL and economic sustainability [61, 62].

In line with the notion of ‘ageing in place’ [63], a home-based, community-centred integrated care model is being proposed as a more effective option [60]. The model focuses on empowering patients through self-management support and using technology such as teleconsultation, telerehabilitation, use of wearables, cellphone applications, etc. to provide integrated care. The iCARE-PD consortium envisions this approach using a technology-based toolkit bringing together all stakeholders [64]. Similarly, a ‘home-hub-and-spoke’ model has been recently proposed for structuring care services, featuring three components: patient’s home, a hub for expert knowledge and an in-between spoke to connect regional members and care managers with the experts [65]. The Proactive and Integrated Management and Empowerment in Parkinson’s Disease (PRIME Parkinson) care model is another ongoing approach that may have greater implications for older PD patients [66]. The care model prioritises empowering the patients and their caregivers and bringing integrated care closer to the patient’s dwelling.

There is increasing evidence that PD patients benefit from palliative care during the late stage of the disease or even earlier [67, 68]. In recent years, there has been a significant evolution in neuro-palliative care in PD [67, 69]. A care model integrating palliative care with standard interdisciplinary care showed beneficial outcomes for patients and caregivers [69]. Yet, palliative care is often underused in PD patients [70] and less integrated into interdisciplinary care plans. Recent guidance recommends PD patients who exhibit evidence of advanced disease, or rapid progression of the disease, or dementia should be considered for palliative care [71]. The PD_Pal clinical trial is set to validate a new model of palliative care to be integrated with the usual care model of PD in Europe [72]. Nonetheless, new care models for PD should consider the local healthcare systems (economic and technological feasibility), clinical practices (availability of various specialities), and social/cultural aspects (patient and caregiver priorities), while also improving the QoL for all PD patients, irrespective of age.

Future direction for PD research in the context of older populations

Older people, with or without PD, represent a heterogeneous population. Some may remain functionally well even during the late stage of life, while others may be frail in their early 60s. Future clinical trials in PD should recruit older people, who are often excluded. For example, despite evidence suggesting the potential benefits of lifestyle interventions in slowing PD progression [57], there is a lack of studies demonstrating their efficacy in advanced-aged patients. Research involving and describing PD patients in low-income regions is limited, and future studies should prioritise investigating the differences in risk or protective factors, or genetics, enabling us to better understand the aetiology of the disease and design care plans accordingly.

Frequent use of telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic has opened possibilities of adopting it for routine clinical care. The effectiveness of telemedicine programmes targeting older PD patients who struggle to access specialised care, particularly in poor-resource regions should also be investigated. Additionally, studies on biomarkers should explore whether novel biomarkers exist or differ for older patients in predicting the progression of PD. The presence of multiple health conditions in old age demands an integrated, patient-centred management of PD to address their individual needs [65]. Future research should attempt to identify suitable care models for improving the QoL for older PD patients.

Conclusion

PD represents a condition that has major implications for the development of geriatric care models and ageing research. Our understanding of PD has elucidated new ways of thinking about the disease, especially shifting the focus to non-motor symptoms and improving the patient’s QoL. Care plans for PD in older adults can only be effective if they are individualised and bring care closer to the patient’s dwelling. We are optimistic that in the near future, we will be able to develop care models and interventions that will greatly enhance the lives of older adults with PD.

Declaration of Conflicts of Interest

None.

Declaration of Sources of Funding

PC received fundings from the national key R&D program of China (2021YFC2501200, 2018YFC1312001, 2017YFC0840105, 2017YFC1310200) and the key realm R&D program of Guangdong province (2018B030337001).

References

Author notes

Jagadish K. Chhetri and Shanshan Mei authors contributed equally.

Comments