-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Adele Pacini, Annabel Stickland, Nuriye Kupeli, Connecting in place: older adults’ experience of online mindfulness therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic, Age and Ageing, Volume 51, Issue 12, December 2022, afac270, https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afac270

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

the negative consequences of COVID-19 distancing measures on older adults’ mental health and ability to access services have been well documented. Online cognitive behavioural therapy and mindfulness interventions for older adults, carried out during the COVID-19 pandemic, have shown that these interventions are feasible and have potential mental health benefits. However, little research has been carried out on older adults’ experiences of engaging with online psychological therapy, and specifically mindfulness therapy.

to understand the experience of older adults engaging with online mindfulness therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic.

a qualitative analysis of four community-based focus groups.

thirty-six community dwelling older adults aged between 65 and 85 years were recruited via older adult organisations, charities and the local press. Nineteen percent had long-term physical health conditions, 25% had severe and enduring mental health difficulties and 19% had mild to moderate mental health difficulties.

there was a strong sense of group cohesion and community from the participants.

Three main themes were identified: reasons for applying, experience of the mindfulness therapy and connecting at home.

the majority of participants were positive about attending a mindfulness group online. This extended to the perceived psychological and social benefits as well as practical considerations. While some participants noted technological hurdles at the beginning of the course, the findings challenge previous studies that suggest older adults are reluctant to engage in online psychological therapies and has important implications for the future provision of psychological therapies to this population.

Key Points

Older adults perceive online mindfulness therapy as beneficial.

Online mindfulness therapy was perceived as supporting older adults’ mental health during COVID-19 lockdown.

Older adults spoke of preferring online therapy to face-to-face groups.

Introduction

Older adults face a steeper recovery curve from COVID-19 than the general population [1] in what has been described as a ‘perfect storm’ for older adult’s mental health [2]. The proportion of over 70s with depression increased from 5% in July 2019 to March 2020 to 10% in June 2020 following 3 months of COVID-19 restrictions [3], and it will be important to consider the accessibility of psychological therapies in the recovery from the pandemic, particularly where anxiety or depression levels are preventing older adults from leaving home [4]. Where older adults’ reluctance to attend face-to-face mental health services is compounded by already stretched mental health services after the pandemic [1], the risk is that a group which is already disproportionately affected by COVID-19 may find it difficult to access appropriate services.

Mobile Health (mHealth), synchronous and asynchronous online therapy groups are a rapidly expanding field which have the potential to improve the accessibility of psychological interventions for older adults. For low intensity intervention, there is some evidence that self-directed online and asynchronous psychological intervention is experienced positively by older adults. Vailati Riboni et al. [5] found that a mindfulness app designed for older adults was reported as beneficial, and improved participants opinions of technology. Hudson et al. [6] reported that older adult caregivers found online mindfulness a positive experience, and that it helped them to develop strategies to support them in their caregiving. This study used optional synchronous web sessions alongside pre-recorded sessions. During the 1-h sessions, participants were able to interact via the web chat function.

Where psychological therapies are directly translated to a synchronous online intervention, studies have reported outcomes of online psychological therapy to support mental health for older adults in Israel [7, 8] and China [9]. These studies all used an intervention based on cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) in combination with mindfulness skills. The interventions were between five and seven sessions long and delivered to either community dwelling older adults [7, 8] or care home residents [9]. The Ying et al. [9] intervention was self-guided with support from clinicians via webchat, and the Shapira et al. [7, 8] sessions were delivered synchronously via zoom. All studies reported significant reductions in loneliness and depression, with Ying et al. [9] additionally reporting reductions in anxiety, functional disability and general psychological distress. Shapira et al. [7] and Ying [9] also found significant reductions on follow-up, 1 month later.

However, there is limited evidence on the acceptability of these interventions, and how they are experienced by participants. Ying et al. [9] reported that 80% of participants would recommend their programme to others, and 88% felt that it was worth doing. However, no acceptability data was provided by the 23% of participants who dropped out of the study, nor was acceptability data provided by Shapira et al. [7, 8]. Thus, there is a clear need to explore the experience of synchronous online psychological therapies for older adults, particularly where they may support psychological recovery from COVID-19.

Thus, the current study looks to understand the experience of older adults engaging with an online mindfulness course during the COVID-19 pandemic. This course was delivered in a fully synchronous format via zoom, with the format and content of the group being directly translated to the online environment as much as possible. The aim of this study is to understand how both the mindfulness therapy and online environment was experienced by participants.

Method

Design

This study is a qualitative descriptive service evaluation of a community-based online 6 week mindfulness for later life (MLL) course.

Participants

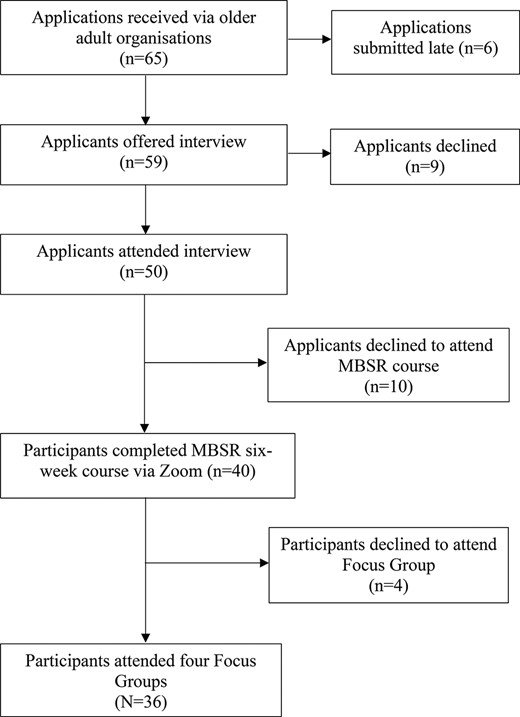

Thirty-six participants attended a focus group following the MLL, and were recruited through adult organisations and charities such as the University of the Third Age and Age UK, and via adverts in the local press. Eligibility was given to those over 65 years who lived in Suffolk or Norfolk, and who could attend at least 4 weeks of the 6-week course. No application received by the cut-off date was rejected. Figure 1 shows the recruitment and intervention procedure.

Flowchart for the number of participants who completed each phase of the study and attrition.

Mindfulness programme

Three MLL courses started on 21 May 2020, 29 September 2020 and 2 February 2021. The assessment interview and course was delivered by the first author (A.P.) who is a chartered Clinical Psychologist and registered mindfulness teacher with the British Association of Mindfulness Based Approaches. The course was based on the mindfulness-based stress reduction programme [10] and ran weekly, for 6 weeks. Each 2-h session comprised two guided practices from the following five options: body scan, mindfulness of breathing, mindfulness of sounds and thoughts, mindful movement and three-step breathing space. In addition, participants were split into smaller ‘breakout’ rooms to discuss a mindfulness topic. Between the sessions, participants were encouraged to listen to the guided mindfulness practices they had been given once a day (formal practice) and had the option to choose everyday tasks to carry out mindfully (informal practice). Participant numbers on each course varied between 8 and 14.

Setting

The focus groups were held online 1 week after completing the MLL course, on 2 July 2020, 17 and 18 November 2020 and 16 March 2021. All participants resided in East Anglia. The first national lockdown due to the coronavirus pandemic began on 26 March 2020 when those who were particularly vulnerable due to underlying medical problems typical to older adults such as cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, diabetes and cancer were advised to ‘shield’ from face to face contact with other people. Aside from these medical issues, older people in general were found to be more vulnerable to COVID-19. Restrictions were eased over the summer of 2020, but the second and third national lockdown began in November 2020 and January 2021, respectively. At the time the final focus group was held, restrictions prevented indoor gatherings, and outdoor meetings were limited to two people from different households. The ‘stay at home’ order remained in place.

Ethical consideration

The data were collected as part of a service development and evaluation programme for the Gatehouse Charity in East Anglia in response to COVID-19, and thus exempt from research ethics approval [11, 12]. Participants provided written informed consent via an online form to participate in the focus group, and for the session to be recorded, and transcribed anonymously. Additional written informed consent was obtained for focus group data to be published in reports and peer-reviewed publications. Information about the structure of the focus group was emailed to each participant. Participants were informed that participation in the focus group, and dissemination of the findings was optional and would not impact on their ability to attend the mindfulness course.

Data collection—focus groups

The four focus groups were held via zoom video conferencing software and facilitated by the second author. Focus groups were organised for each MLL group separately, so participants took part in a discussion with participants from their course. Each group comprised between 7 and 12 participants and ran for 1–1½ h. A semi-structured topic guide (Supplementary Appendix A) was used to explore their experiences of completing the intervention online and their experiences of completing the practices as part of a group and from their own home.

Data analysis

Focus group data was audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. For accuracy, transcripts were checked against audio recordings by the second author (A.S.). To achieve familiarisation with the data, A.S. and the third author (N,K.) read each transcript several times before coding independently using reflexive thematic analysis [13, 14]. Codes were iteratively generated to capture key experiences and feelings expressed by the participants, alongside what prompted them to sign up for the online course or continue with it once it had commenced. The collaborative approach was used to achieve a more nuanced interpretivist perspective and developing themes were critically reviewed by the first author (A.P.) to verify ‘patterns of shared meaning’ [14].

Results

The participants were predominantly female (72%) and all were white European. Most participants (86%) held, or had held, professional or intermediate occupations. Based on self-report data and assessment interview, 19% had long-term physical health conditions, 25% had severe and enduring mental health difficulties, and 19% had mild to moderate mental health difficulties (Table 1). We used the definition of severe mental illness as one which is ‘prolonged and recurrent, impair[s] activities of daily living, and require[s] long-term treatment. Common diagnoses include schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression’ [15]. Conversely, mild to moderate mental health difficulties were those which were not recurrent, did not require long-term treatment or impair activities of daily living. These data were collected as part of the online application process, before the MLL groups began. Most participants (83%) attended all six of the course sessions, 14% attended five and 3% attended four.

| . | No (%) . | Age range (years) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | 65–70 . | 71–75 . | 76–80 . | 81–85 . |

| All participants Gender | 36 (100%) | 17 (47%) | 8 (23%) | 6 (17%) | 5 (13%) |

| 10 (28%) | 4 (11%) | 2 (6%) | 1 (3%) | 3 (8%) |

| 26 (72%) | 13 (36%) | 6 (17%) | 5 (14%) | 2 (5%) |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| 36 (100%) | 17 (47%) | 8 (23%) | 6 (17%) | 5 (13%) |

| Residency | |||||

| 13 (36%) | 4 (11%) | 3 (8%) | 2 (6%) | 4 (11%) |

| 23 (64%) | 13 (36%) | 5 (14%) | 4 (11%) | 1 (3%) |

| Occupation | |||||

| 18 (50%) | 11 (31%) | 1 (3%) | 2 (6%) | 4 (11%) |

| 13 (36%) | 5 (14%) | 5 (14%) | 3 (8%) | 0 (0%) |

| 5 (14%) | 1 (3%) | 2 (6%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) |

| Health | |||||

| 7 (19%) | 3 (8%) | 2 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (6%) |

| 9 (25%) | 4 (14%) | 3 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (5%) |

| 7 (19%) | 3 (8%) | 3 (8%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Course Attendance | |||||

| 6 sessions | 30 (83%) | 15 (42%) | 6 (17%) | 5 (13%) | 4 (11%) |

| 5 sessions | 5 (14%) | 2 (5%) | 2 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) |

| 4 sessions | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) |

| . | No (%) . | Age range (years) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | 65–70 . | 71–75 . | 76–80 . | 81–85 . |

| All participants Gender | 36 (100%) | 17 (47%) | 8 (23%) | 6 (17%) | 5 (13%) |

| 10 (28%) | 4 (11%) | 2 (6%) | 1 (3%) | 3 (8%) |

| 26 (72%) | 13 (36%) | 6 (17%) | 5 (14%) | 2 (5%) |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| 36 (100%) | 17 (47%) | 8 (23%) | 6 (17%) | 5 (13%) |

| Residency | |||||

| 13 (36%) | 4 (11%) | 3 (8%) | 2 (6%) | 4 (11%) |

| 23 (64%) | 13 (36%) | 5 (14%) | 4 (11%) | 1 (3%) |

| Occupation | |||||

| 18 (50%) | 11 (31%) | 1 (3%) | 2 (6%) | 4 (11%) |

| 13 (36%) | 5 (14%) | 5 (14%) | 3 (8%) | 0 (0%) |

| 5 (14%) | 1 (3%) | 2 (6%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) |

| Health | |||||

| 7 (19%) | 3 (8%) | 2 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (6%) |

| 9 (25%) | 4 (14%) | 3 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (5%) |

| 7 (19%) | 3 (8%) | 3 (8%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Course Attendance | |||||

| 6 sessions | 30 (83%) | 15 (42%) | 6 (17%) | 5 (13%) | 4 (11%) |

| 5 sessions | 5 (14%) | 2 (5%) | 2 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) |

| 4 sessions | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) |

| . | No (%) . | Age range (years) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | 65–70 . | 71–75 . | 76–80 . | 81–85 . |

| All participants Gender | 36 (100%) | 17 (47%) | 8 (23%) | 6 (17%) | 5 (13%) |

| 10 (28%) | 4 (11%) | 2 (6%) | 1 (3%) | 3 (8%) |

| 26 (72%) | 13 (36%) | 6 (17%) | 5 (14%) | 2 (5%) |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| 36 (100%) | 17 (47%) | 8 (23%) | 6 (17%) | 5 (13%) |

| Residency | |||||

| 13 (36%) | 4 (11%) | 3 (8%) | 2 (6%) | 4 (11%) |

| 23 (64%) | 13 (36%) | 5 (14%) | 4 (11%) | 1 (3%) |

| Occupation | |||||

| 18 (50%) | 11 (31%) | 1 (3%) | 2 (6%) | 4 (11%) |

| 13 (36%) | 5 (14%) | 5 (14%) | 3 (8%) | 0 (0%) |

| 5 (14%) | 1 (3%) | 2 (6%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) |

| Health | |||||

| 7 (19%) | 3 (8%) | 2 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (6%) |

| 9 (25%) | 4 (14%) | 3 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (5%) |

| 7 (19%) | 3 (8%) | 3 (8%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Course Attendance | |||||

| 6 sessions | 30 (83%) | 15 (42%) | 6 (17%) | 5 (13%) | 4 (11%) |

| 5 sessions | 5 (14%) | 2 (5%) | 2 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) |

| 4 sessions | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) |

| . | No (%) . | Age range (years) . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | 65–70 . | 71–75 . | 76–80 . | 81–85 . |

| All participants Gender | 36 (100%) | 17 (47%) | 8 (23%) | 6 (17%) | 5 (13%) |

| 10 (28%) | 4 (11%) | 2 (6%) | 1 (3%) | 3 (8%) |

| 26 (72%) | 13 (36%) | 6 (17%) | 5 (14%) | 2 (5%) |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| 36 (100%) | 17 (47%) | 8 (23%) | 6 (17%) | 5 (13%) |

| Residency | |||||

| 13 (36%) | 4 (11%) | 3 (8%) | 2 (6%) | 4 (11%) |

| 23 (64%) | 13 (36%) | 5 (14%) | 4 (11%) | 1 (3%) |

| Occupation | |||||

| 18 (50%) | 11 (31%) | 1 (3%) | 2 (6%) | 4 (11%) |

| 13 (36%) | 5 (14%) | 5 (14%) | 3 (8%) | 0 (0%) |

| 5 (14%) | 1 (3%) | 2 (6%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) |

| Health | |||||

| 7 (19%) | 3 (8%) | 2 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (6%) |

| 9 (25%) | 4 (14%) | 3 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (5%) |

| 7 (19%) | 3 (8%) | 3 (8%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Course Attendance | |||||

| 6 sessions | 30 (83%) | 15 (42%) | 6 (17%) | 5 (13%) | 4 (11%) |

| 5 sessions | 5 (14%) | 2 (5%) | 2 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) |

| 4 sessions | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) |

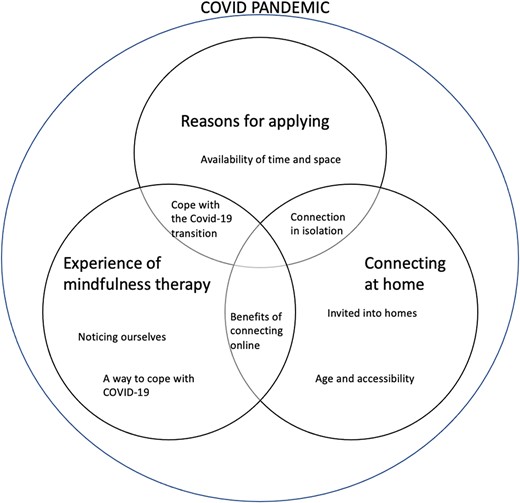

Three main themes were developed from the focus group data: reasons for applying, experience of mindfulness therapy and connecting at home (Figure 2). We discuss these themes below in relation to older adults’ experience of engaging with online therapy during COVID-19.

Themes and subthemes and the relationship between them in the context of COVID-19.

A subtheme was mapped as overlapping where it merged across two or more themes: the subthemes are discussed under the theme in which most of the participant’s discussion took place. As indicated by Figure 2, the experiences of the participants were framed within the unique context of the COVID pandemic. Whilst participants contextualised each of the themes within the COVID pandemic to varying degrees, subthemes also overlapped in important ways. For example, the experience of video conferencing was in some ways inseparable from the necessity of using this technology at home, of the type of therapy delivered via it, and the reason for engaging with it in the first place. Table 2 outlines the themes and subthemes against their illustrative data extracts.

| Themes . | Subthemes . | Illustrative data extracts . |

|---|---|---|

| Reasons for applying | To cope with the COVID-19 transition | ‘… from going from a really busy life to a houseful, always cooking for people to nothing. . . [the mindfulness course] did bring me through a really, really dark tunnel’ (AC70f) ‘. . . I was looking for something that I could reach out to other people. . . something that stopped the loneliness’ (AC70f) ‘I came on the course because I wasn’t coping very well’ (PM74f) |

| Availability of time and space | ‘I wouldn’t have done it [if there was no lockdown] as I would have been doing other things . . . COVID has given me a Thursday for another opportunity’(KS66m) ‘. . . it’s been a time to try new things really’ (ZD68f) ‘I think if it hadn’t been for Covid, we probably wouldn’t have done because life is busy, busy and you know you don’t, we have sort of had very little other things, or a few other things to do during the epidemic’ (DH78f) | |

| Experience of the mindfulness therapy | A way to cope with COVID-19 | ‘. . . three minutes to calm myself down if I feel anxious. I haven’t been able to see my family for a long time and it was starting to get to me, so it did help me enormously’ (GW69f) ‘. . . having been shielding. . . for the last three months. . . it’s been relaxing. . . I’ve thoroughly enjoyed it and I’m grateful for it’ (JB71f) ‘Because I find it difficult to not plan ahead and the whole uncertainty of the current situation where we don’t know, whether we’ll be able to go back to work, whether we’ll be able to visit family, all those things. I found it [mindfulness course] really helpful in living in the present and not planning ahead all of the time’ (MD67f) ‘And it’s so nice to for somebody to say it’s okay. You know, um, I think that came up for me. And all that nourishment, to sort of nourish one’s soul’ (GS84f) |

| Noticing ourselves | ‘I now can recognise that I’m not being patient with her’ (SD71m) ‘. . . it’s made me switch off from other things. . . take stock. . .’ (DC69m) ‘I’m no longer ashamed of being this way anymore. I’m no longer hiding it’ (AC70f) ‘It’s such a joy to be able to see something good in cases where things aren’t good. And things happening to be able to find that happiness, that loveliness, and that peace from it just coming into your body. And you just feel it’ (JD76f) | |

| Connecting at home | Benefits of connecting online | ‘…it’s worked really well, and so much more relaxed with Zoom, it’s been nice meeting everyone in this way’ (DC69m) ‘Having the Zoom meeting. . . for me, was better than. . . taking the time to go somewhere. . . It was nice to be able to just pop up, here we are’ (LR71f) ‘I couldn’t have done that course if it had taken place somewhere because physically, I wouldn’t have been in a position to take myself there and back and the walking involved and so on. . .whereas being at home. . .yes, it made it very easy for me’ (BU66f) |

| Invited into homes | ‘. . . it’s a strange dichotomy. . . we were less together because we were not face to face, but on the other hand, we’re in everyone else’s home. So, we’re kind of, in a sense, more connected, because. . . of that instead of . . . office building or something’(DC69m) ‘. . . it’s been a lot more cosy experience, almost a one to one experience, although I can see everyone along the top rail there which makes it a group experience’(KS66m) | |

| Connection in isolation | ‘I think a word that’s come out of this is community, and we’ve probably made our own community in this group’(GS84) ‘[I got out of the course] far more than I was expecting. . . getting to know so many people and I was really surprised. . . when people opened up to how they were feeling and what effect this. . .Coronavirus had on them’(BU66f) ‘Seeing all your faces has meant a lot to me. . . I haven’t seen anybody’(GH80f) ‘I realise that there is a community out there that has the same problems and the same issues’(AC70f) | |

| Age and Accessibility | ‘For so many people our age, technology is an obstacle rather than an aid’(SD71f) ‘I’m on an iPad. So I have to flick over when somebody on the second page. But then I think it’s been a learning experience. And part of it has been that we’ve had to concentrate on that, and it actually has helped. And because we concentrate on what I’ve got to do next you forget you’re anxious. You forget you’re struggling. That in itself has actually been a useful tool’ (AC70f) |

| Themes . | Subthemes . | Illustrative data extracts . |

|---|---|---|

| Reasons for applying | To cope with the COVID-19 transition | ‘… from going from a really busy life to a houseful, always cooking for people to nothing. . . [the mindfulness course] did bring me through a really, really dark tunnel’ (AC70f) ‘. . . I was looking for something that I could reach out to other people. . . something that stopped the loneliness’ (AC70f) ‘I came on the course because I wasn’t coping very well’ (PM74f) |

| Availability of time and space | ‘I wouldn’t have done it [if there was no lockdown] as I would have been doing other things . . . COVID has given me a Thursday for another opportunity’(KS66m) ‘. . . it’s been a time to try new things really’ (ZD68f) ‘I think if it hadn’t been for Covid, we probably wouldn’t have done because life is busy, busy and you know you don’t, we have sort of had very little other things, or a few other things to do during the epidemic’ (DH78f) | |

| Experience of the mindfulness therapy | A way to cope with COVID-19 | ‘. . . three minutes to calm myself down if I feel anxious. I haven’t been able to see my family for a long time and it was starting to get to me, so it did help me enormously’ (GW69f) ‘. . . having been shielding. . . for the last three months. . . it’s been relaxing. . . I’ve thoroughly enjoyed it and I’m grateful for it’ (JB71f) ‘Because I find it difficult to not plan ahead and the whole uncertainty of the current situation where we don’t know, whether we’ll be able to go back to work, whether we’ll be able to visit family, all those things. I found it [mindfulness course] really helpful in living in the present and not planning ahead all of the time’ (MD67f) ‘And it’s so nice to for somebody to say it’s okay. You know, um, I think that came up for me. And all that nourishment, to sort of nourish one’s soul’ (GS84f) |

| Noticing ourselves | ‘I now can recognise that I’m not being patient with her’ (SD71m) ‘. . . it’s made me switch off from other things. . . take stock. . .’ (DC69m) ‘I’m no longer ashamed of being this way anymore. I’m no longer hiding it’ (AC70f) ‘It’s such a joy to be able to see something good in cases where things aren’t good. And things happening to be able to find that happiness, that loveliness, and that peace from it just coming into your body. And you just feel it’ (JD76f) | |

| Connecting at home | Benefits of connecting online | ‘…it’s worked really well, and so much more relaxed with Zoom, it’s been nice meeting everyone in this way’ (DC69m) ‘Having the Zoom meeting. . . for me, was better than. . . taking the time to go somewhere. . . It was nice to be able to just pop up, here we are’ (LR71f) ‘I couldn’t have done that course if it had taken place somewhere because physically, I wouldn’t have been in a position to take myself there and back and the walking involved and so on. . .whereas being at home. . .yes, it made it very easy for me’ (BU66f) |

| Invited into homes | ‘. . . it’s a strange dichotomy. . . we were less together because we were not face to face, but on the other hand, we’re in everyone else’s home. So, we’re kind of, in a sense, more connected, because. . . of that instead of . . . office building or something’(DC69m) ‘. . . it’s been a lot more cosy experience, almost a one to one experience, although I can see everyone along the top rail there which makes it a group experience’(KS66m) | |

| Connection in isolation | ‘I think a word that’s come out of this is community, and we’ve probably made our own community in this group’(GS84) ‘[I got out of the course] far more than I was expecting. . . getting to know so many people and I was really surprised. . . when people opened up to how they were feeling and what effect this. . .Coronavirus had on them’(BU66f) ‘Seeing all your faces has meant a lot to me. . . I haven’t seen anybody’(GH80f) ‘I realise that there is a community out there that has the same problems and the same issues’(AC70f) | |

| Age and Accessibility | ‘For so many people our age, technology is an obstacle rather than an aid’(SD71f) ‘I’m on an iPad. So I have to flick over when somebody on the second page. But then I think it’s been a learning experience. And part of it has been that we’ve had to concentrate on that, and it actually has helped. And because we concentrate on what I’ve got to do next you forget you’re anxious. You forget you’re struggling. That in itself has actually been a useful tool’ (AC70f) |

| Themes . | Subthemes . | Illustrative data extracts . |

|---|---|---|

| Reasons for applying | To cope with the COVID-19 transition | ‘… from going from a really busy life to a houseful, always cooking for people to nothing. . . [the mindfulness course] did bring me through a really, really dark tunnel’ (AC70f) ‘. . . I was looking for something that I could reach out to other people. . . something that stopped the loneliness’ (AC70f) ‘I came on the course because I wasn’t coping very well’ (PM74f) |

| Availability of time and space | ‘I wouldn’t have done it [if there was no lockdown] as I would have been doing other things . . . COVID has given me a Thursday for another opportunity’(KS66m) ‘. . . it’s been a time to try new things really’ (ZD68f) ‘I think if it hadn’t been for Covid, we probably wouldn’t have done because life is busy, busy and you know you don’t, we have sort of had very little other things, or a few other things to do during the epidemic’ (DH78f) | |

| Experience of the mindfulness therapy | A way to cope with COVID-19 | ‘. . . three minutes to calm myself down if I feel anxious. I haven’t been able to see my family for a long time and it was starting to get to me, so it did help me enormously’ (GW69f) ‘. . . having been shielding. . . for the last three months. . . it’s been relaxing. . . I’ve thoroughly enjoyed it and I’m grateful for it’ (JB71f) ‘Because I find it difficult to not plan ahead and the whole uncertainty of the current situation where we don’t know, whether we’ll be able to go back to work, whether we’ll be able to visit family, all those things. I found it [mindfulness course] really helpful in living in the present and not planning ahead all of the time’ (MD67f) ‘And it’s so nice to for somebody to say it’s okay. You know, um, I think that came up for me. And all that nourishment, to sort of nourish one’s soul’ (GS84f) |

| Noticing ourselves | ‘I now can recognise that I’m not being patient with her’ (SD71m) ‘. . . it’s made me switch off from other things. . . take stock. . .’ (DC69m) ‘I’m no longer ashamed of being this way anymore. I’m no longer hiding it’ (AC70f) ‘It’s such a joy to be able to see something good in cases where things aren’t good. And things happening to be able to find that happiness, that loveliness, and that peace from it just coming into your body. And you just feel it’ (JD76f) | |

| Connecting at home | Benefits of connecting online | ‘…it’s worked really well, and so much more relaxed with Zoom, it’s been nice meeting everyone in this way’ (DC69m) ‘Having the Zoom meeting. . . for me, was better than. . . taking the time to go somewhere. . . It was nice to be able to just pop up, here we are’ (LR71f) ‘I couldn’t have done that course if it had taken place somewhere because physically, I wouldn’t have been in a position to take myself there and back and the walking involved and so on. . .whereas being at home. . .yes, it made it very easy for me’ (BU66f) |

| Invited into homes | ‘. . . it’s a strange dichotomy. . . we were less together because we were not face to face, but on the other hand, we’re in everyone else’s home. So, we’re kind of, in a sense, more connected, because. . . of that instead of . . . office building or something’(DC69m) ‘. . . it’s been a lot more cosy experience, almost a one to one experience, although I can see everyone along the top rail there which makes it a group experience’(KS66m) | |

| Connection in isolation | ‘I think a word that’s come out of this is community, and we’ve probably made our own community in this group’(GS84) ‘[I got out of the course] far more than I was expecting. . . getting to know so many people and I was really surprised. . . when people opened up to how they were feeling and what effect this. . .Coronavirus had on them’(BU66f) ‘Seeing all your faces has meant a lot to me. . . I haven’t seen anybody’(GH80f) ‘I realise that there is a community out there that has the same problems and the same issues’(AC70f) | |

| Age and Accessibility | ‘For so many people our age, technology is an obstacle rather than an aid’(SD71f) ‘I’m on an iPad. So I have to flick over when somebody on the second page. But then I think it’s been a learning experience. And part of it has been that we’ve had to concentrate on that, and it actually has helped. And because we concentrate on what I’ve got to do next you forget you’re anxious. You forget you’re struggling. That in itself has actually been a useful tool’ (AC70f) |

| Themes . | Subthemes . | Illustrative data extracts . |

|---|---|---|

| Reasons for applying | To cope with the COVID-19 transition | ‘… from going from a really busy life to a houseful, always cooking for people to nothing. . . [the mindfulness course] did bring me through a really, really dark tunnel’ (AC70f) ‘. . . I was looking for something that I could reach out to other people. . . something that stopped the loneliness’ (AC70f) ‘I came on the course because I wasn’t coping very well’ (PM74f) |

| Availability of time and space | ‘I wouldn’t have done it [if there was no lockdown] as I would have been doing other things . . . COVID has given me a Thursday for another opportunity’(KS66m) ‘. . . it’s been a time to try new things really’ (ZD68f) ‘I think if it hadn’t been for Covid, we probably wouldn’t have done because life is busy, busy and you know you don’t, we have sort of had very little other things, or a few other things to do during the epidemic’ (DH78f) | |

| Experience of the mindfulness therapy | A way to cope with COVID-19 | ‘. . . three minutes to calm myself down if I feel anxious. I haven’t been able to see my family for a long time and it was starting to get to me, so it did help me enormously’ (GW69f) ‘. . . having been shielding. . . for the last three months. . . it’s been relaxing. . . I’ve thoroughly enjoyed it and I’m grateful for it’ (JB71f) ‘Because I find it difficult to not plan ahead and the whole uncertainty of the current situation where we don’t know, whether we’ll be able to go back to work, whether we’ll be able to visit family, all those things. I found it [mindfulness course] really helpful in living in the present and not planning ahead all of the time’ (MD67f) ‘And it’s so nice to for somebody to say it’s okay. You know, um, I think that came up for me. And all that nourishment, to sort of nourish one’s soul’ (GS84f) |

| Noticing ourselves | ‘I now can recognise that I’m not being patient with her’ (SD71m) ‘. . . it’s made me switch off from other things. . . take stock. . .’ (DC69m) ‘I’m no longer ashamed of being this way anymore. I’m no longer hiding it’ (AC70f) ‘It’s such a joy to be able to see something good in cases where things aren’t good. And things happening to be able to find that happiness, that loveliness, and that peace from it just coming into your body. And you just feel it’ (JD76f) | |

| Connecting at home | Benefits of connecting online | ‘…it’s worked really well, and so much more relaxed with Zoom, it’s been nice meeting everyone in this way’ (DC69m) ‘Having the Zoom meeting. . . for me, was better than. . . taking the time to go somewhere. . . It was nice to be able to just pop up, here we are’ (LR71f) ‘I couldn’t have done that course if it had taken place somewhere because physically, I wouldn’t have been in a position to take myself there and back and the walking involved and so on. . .whereas being at home. . .yes, it made it very easy for me’ (BU66f) |

| Invited into homes | ‘. . . it’s a strange dichotomy. . . we were less together because we were not face to face, but on the other hand, we’re in everyone else’s home. So, we’re kind of, in a sense, more connected, because. . . of that instead of . . . office building or something’(DC69m) ‘. . . it’s been a lot more cosy experience, almost a one to one experience, although I can see everyone along the top rail there which makes it a group experience’(KS66m) | |

| Connection in isolation | ‘I think a word that’s come out of this is community, and we’ve probably made our own community in this group’(GS84) ‘[I got out of the course] far more than I was expecting. . . getting to know so many people and I was really surprised. . . when people opened up to how they were feeling and what effect this. . .Coronavirus had on them’(BU66f) ‘Seeing all your faces has meant a lot to me. . . I haven’t seen anybody’(GH80f) ‘I realise that there is a community out there that has the same problems and the same issues’(AC70f) | |

| Age and Accessibility | ‘For so many people our age, technology is an obstacle rather than an aid’(SD71f) ‘I’m on an iPad. So I have to flick over when somebody on the second page. But then I think it’s been a learning experience. And part of it has been that we’ve had to concentrate on that, and it actually has helped. And because we concentrate on what I’ve got to do next you forget you’re anxious. You forget you’re struggling. That in itself has actually been a useful tool’ (AC70f) |

Reasons for applying

To cope with the COVID-19 transition

The transition brought about by COVID-19 came through strongly in participants’ reasons for attending the course; however, this manifested in different ways. For some, the experience of COVID-19 restrictions was a transition ‘to nothing’, which one participant experienced as ‘a really, really dark tunnel’ (AC70f). For others, it led to feelings of loneliness either in a general sense ‘… I was looking for something that I could reach out to other people… something that stopped the loneliness’ (GH83f) or specifically in relation to family ‘I haven’t been able to see my family for a long time and it was starting to get to me’ (GH68f). For others, it was a transition that meant feeling like ‘everything was sort of upon us’ from the pressures of practical tasks ‘planning meals… finding new ways of shopping and getting supplies in’ (GS84). Others spoke of feeling part of a societal transition that was reacting against being ‘bombarded…24 hours a day, if you want, by everything that’s going wrong with the world’ (SD71m). For them, mindfulness was a tool that ‘allows you to just sit back, breathe…’ (SD71m).

Availability of time and space

Some participants found that the restrictions placed on them during the pandemic freed up the time or mental space that they sought to make the most of by applying to the group. A 66-year-old male reported that he was only able to take part in the course because the pandemic restrictions meant he could no longer do the things he would normally have done:

I wouldn’t have done it [if there was no lockdown] as I would have been doing other things … COVID has given me a Thursday for another opportunity. (KS66m)

Although participants reported that it had been difficult not being able to do the things they would normally do, they described that the period of lockdown restrictions gave them the space to concentrate on learning new skills:

Well, it’s been a time to try new things really, hasn’t it, to learn new skills, … I’d try to teach myself to do some patchwork quilting from YouTube so I managed to do that, so I’ve finished that now so I’m looking for the next project … overall, it’s been good for me in that respect, obviously not being able to go out has been difficult but I’ve found different things to fill my time and learning throughout the time really, different, different things I never knew before. (ZD68f)

Other participants found the increased time and space a source of increased anxiety and low mood. Partially overlapping with the theme above, they applied for the mindfulness course to help them cope with these changes ‘I thought that’s just what I need, because I was suffering from a racing mind. And it got worse, I think with the advent of COVID and we were at home all the time’ (GS84f).

Experience of the mindfulness therapy

A way to cope with COVID-19

Meeting the hopes of participants in applying to the course, many spoke about how mindfulness helped them to cope with COVID-19. Participants reported how anxious the pandemic had made them and, as one individual stated, the mindfulness course had given her the tools to ‘relax and reduce anxiety’ (GW69f) when she needed it. These tools helped the participants deal with the uncertainty of the pandemic and life’s challenges, and the structure of the course itself was appreciated at a time of change and instability ‘there was always an introduction to a new technique, and it was good that it was introduced within the group obviously and the learning process took place within the group’ (BU66f).

Living in the present became valuable to many participants as plans had to change due to factors outside of their control and being encouraged to focus on the present helped with anxiety around an uncertain future ‘just live in the moment, realise that thoughts of the future, and worry and so on are best left there. Just, just concentrate on the moment. That’s what I tried to do with it and that has helped me’ (PH70m).

Moving beyond simply ‘coping’, for some participants the practice of mindfulness brought a sense of gratitude. ‘We’re having to live through this virus, this awful time. But there’s still room for us to find good and niceness and everything else’ (JD76), or of noticing the small things in life that previously went unnoticed. ‘The one thing that I look at from where I’m sitting here at the moment and looking out of my window. I’ve got a lovely view’ (AH84m).

Noticing ourselves

Several participants valued the time to switch attention away from external events and on to themselves and some participants mentioned that the lockdown and the mindfulness combined contributed to more self-reflection, a time to step back and become more aware of themselves and how they relate to others. For some people, this was an uncomfortable but helpful process whether noticing that they had little interaction with others ‘I have found it really helpful in recognising and facing up to the fact that I’ve been very insular. And very late in life. I’m sorry, it didn’t happen earlier. But timing is all, it seems to me’ (PD80f) or that their interactions do not always reflect how they are feeling ‘I think a big thing that I learned through this, having a big family and, and talking to them, they’ll say you alright, Nan? Are you alright, Mum? Yes, I’m fine. Thanks. How are you? In this group it’s been okay for me to be not okay’ (AC70f).

For other participants a stronger connection to themselves was a source of joy ‘It’s such a joy to be able to see something good in cases where things aren’t good. And things happening to be able to find that happiness, that loveliness, and that peace from it just coming into your body. And you just feel it’ (JD76f).

Connecting at home

Benefits of connecting online

The benefits of connecting online were experienced both emotionally and practically, with these two aspects overlapping at times, and seen as enhancing the practice of mindfulness in the group. Participants reported arriving at the session calmer than they would have been if they had to travel and find parking/transport environment ‘… for me, the stress of having to go somewhere, finding somewhere to park etc, and getting there on time, would really have added a lot of stress. And this was just wonderful because you started the session 95% of the time… in already a more relaxed state than you would have done if you’d had to drive somewhere’ (RT69f). Many said they felt more relaxed meeting new people ‘… the beauty of zoom is that you bring it into your home, to your own environment... so yeah, you become relaxed and meeting other people at the same time’ (RC71m). Practicing in the familiarity of their own home and remaining relaxed after the session with no need to abruptly change pace was beneficial ‘… it meant no transport… we can just do it from home… because it’s a very good time to feel completely relaxed afterwards’ (LR71f).

Running the group online was also considered to be accessible to a wider reach of older people, particularly those who would have found travel difficult due to distance, or physical pain/illness ‘I couldn’t have done that course if it had taken place somewhere because physically, I wouldn’t have been in a position to take myself there and back and the walking involved and so on…whereas being at home…yes, it made it very easy for me’ (BU66f).

There was apprehension around travelling and ‘being forgotten’ if services resume face-to-face interactions ‘I’m mainly housebound, so I wouldn’t be able to get anywhere to do this sort of thing and I do hope that when we go back to normal, whatever that is, people won’t forget the housebound’ (PM74f).

One participant commented that video conferencing enabled them to attend the course during adverse weather conditions, especially as she lived in a more rural area ‘… it opens up the opportunities for more people in more places whereas otherwise you’d have… to go somewhere that was more local to you. And you might be living in a place like where I live which is semi-rural … I would be limited in what I could do…’ (SR69f) and some participants described how the online delivery meant they could meet people who they would otherwise never have met as geographically they lived a distance apart ‘…getting to and from a group such as ours who live over quite a wide area, maybe we wouldn’t have got together’ (PD80m).

Invited into homes

Many of the participants reported that being ‘invited’ (PH70m) into each other’s homes led to a feeling of intimacy and cosiness ‘… the impact on me is that it’s been a lot more cosy experience, almost a one to one experience, although I can see everyone along the top rail there which makes it a group experience’ (KS66m).

Seeing people in their home environment helped build relationships ‘It’s far easier to get to know people in this environment…when you’re seeing them warts and all’ (SD71f) and although one individual found the online format meant he found it harder to connect with others initially, this improved over time ‘I think the fact we haven’t seen each other face to face… maybe would have been nice to have just one, one session where we can see each other in the flesh and then continue online… It’s just that it takes me longer to connect with the rest really, but I think you get used to it after seven weeks’ (SS80m).

Connection in isolation

Many participants described how connections made within the group made them feel less alone during the pandemic and lockdown ‘I’ve found that most helpful, that I’m not alone in the struggle through this’ (AC70f). They looked forward to meeting everybody each week and the group became a supportive and valued community ‘I realise that there is a community out there that has the same problems and the same issues’ (AC70f). The ability to move between the whole group and smaller ‘breakout room’ groups was seen as supporting individual relationships ‘We went in the rooms and somebody was talking directly to me…it’s a shared experience… and I began to open my mind’ (GH80f) and ‘It just made me feel more relaxed… that I’d actually chatted to somebody…so I’d have almost liked to have met everybody in a breakout room… because I found that helpful’ (GH80f). This in turn led to more openness to the therapy ‘… if you are feeling really, really poor you can say what you’re feeling at the time and then maybe everybody else is feeling, you know, empathising with you and it makes you feel more relaxed going on further in the session’ (AP69f).

Age and accessibility

Of course, using the online platform was not without its difficulties. Participants tended to frame difficulties in relation to their age, rather than connectivity or hardware limitations ‘… if you’re not used to handling the technology, just getting it there on your computer, so you can actually use it day in and day out, is quite hard to do’ (SD71f). Other participants noted that there were emotional or cognitive benefits to developing computer skills ‘I like being as knowledgeable as I can. So, I get quite stubborn about finding out how to do it’ (PD80f). Participants were also aware that the online format would make the course inaccessible for some older adults ‘It wouldn’t be open to some people for that reason’ (PH70m).

Discussion

This paper explored older adults experience of engaging with an online mindfulness course for later life course during the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants were largely positive about their experience of attending a mindfulness therapy group online. This extended to the psychological and social benefits as well as practical considerations. There was a strong sense of group cohesion and community, as well as a gratitude for being able to engage with mindfulness as a support through COVID-19. Whilst some participants noted challenges to using technology, particularly at the beginning of the course, the findings support the Ying et al. study [9] showing that older adults felt that it was worth engaging with an online psychological therapy.

Of course, we need to consider the social context of the pandemic in shaping the extent to which videoconferencing has been used, and the impetus for people to find tools to help them navigate the challenges of the pandemic. National lockdowns left participants feeling isolated, lonely and missing usual social interactions, as is well documented in current literature [2], and the intervention gave them the opportunity to connect socially online. Some participants found aspects of the technology challenging, but all participants were able to access and engage with the course.

With time freed up from cancelled social engagements, participants reported being more able to commit to the course timetable and apply themselves to the content. This is also evident by the high course attendance. Participation in the online course provided structure and stability in an uncertain world. Participants reported they were able to use what they had learned to manage feelings of anxiety, remain calmer in stressful situations brought on by the pandemic such as inability to see their family, and acceptance of situations outside of their control, for example absence of usual valued National Health Service (NHS) services [1]. Consistent with the findings from Hudson et al. [6] they were also able to develop their self-reflection by learning to turn their attention away from external events and find calm by looking inwards, both during the online sessions and afterwards.

Consistent with previous research on online healthcare with older adults [1], we heard that most participants found attending the group at home was more convenient than travelling to a venue. Some participants were housebound or suffered physical disabilities where sitting for a period of time was uncomfortable. Similarly, many of our participants lived in rural areas which were considered to be too remote from the towns where face-to-face groups would normally be held.

Beyond the practicalities, participants reported feeling more relaxed in their own home environment which contributed to an openness to both the therapy and relationships within the group. Most participants felt more confident meeting strangers in an already familiar environment. Overall, meeting the other group members over video conferencing as opposed to face to face did not seem to inhibit group cohesiveness. In fact, it tended to enhance the level of intimacy experienced, participants felt that they had been invited into each other’s homes. They were able to see, for example, photographs, décor and pets and this familiarity with others home environment may have contributed positively to sharing feelings and vulnerabilities in the group. Despite not sharing the same physical space as other group members, most participants reported experiencing a sense of fellowship during group mindfulness practices.

Strengths and limitations

There are some limitations of our research. Most participants were female and all lived with family members or independently, and our research did not cover adults in later life who lived in a care home.

Most participants had held higher managerial or professional roles and were white British, and so further work may benefit from engaging with other socioeconomic and ethnic groups and those that may have had minimal use of computers in their working career. Indeed, some participants thought that the technology involved with the online course would put some people off applying.

Notwithstanding the limitations, this study has some notable strengths. Firstly, as an online intervention, participants could have been anywhere in the country allowing those who may not participate in interventions or research to do so. This is the first study to explore older adults’ experiences of attending an online mindfulness intervention and provides useful insights into what works and how interventions can be designed to overcome any barriers to implementing psychological therapies online for this population.

Implications for research, clinical practice and policy

Going forward it will be important to have a more nuanced discussion of the appropriateness and acceptability of online psychological therapy. We need to consider the types of online therapy more closely, for example, the level of social interaction with an app is quite different from a synchronous zoom session. However, our findings challenge the idea that ‘ageing in place’ reflects a passive process of older adults receiving care in their homes and of adaptations being made to limit reductions in independence [16]. For inclusivity, future research could focus on assessing the acceptability and feasibility of using a hybrid model to provide psychological therapies to enable both those who prefer to join face to face and online to participate.

These findings also have important implications for clinical practice and policy when providing and commissioning psychological therapies for this population. In contrast to the dominant narrative of older adults being unwilling or unable to engage in online psychological therapy, our findings reflect that older adult participants in the mindfulness for later life group experienced connection both to the facilitator and to other group members. This fostered a sense of community, offered a safe haven during COVID-19 and allowed participants to not only age in place [17, 18] but also ‘connect in place’. Importantly, this reduced the impact of living in a rural location, difficulties attending face-to-face settings due to COVID-19 and built on the sense of safety that attending from home provided.

Conclusion

Our findings are characterised by participants’ impetus and willingness to engage online, utilising technology to overcome practical and societal barriers, and importantly, ‘connecting in place’ and experiencing an improvement in their mental well-being and social connections despite the COVID-19 pandemic.

Declaration of Conflicts of Interest

None.

Declaration of Funding

A.P. and A.S. were supported by an East and West Suffolk Clinical Commissioning Group Equity in Mind project grant. N.K. was supported by Alzheimer’s Society Junior Fellowship grant funding (Grant Award number: 399 AS-JF- 17b-016).

Comments