-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jiong Tu, Haiyan Li, Bei Ye, Jing Liao, The trajectory of family caregiving for older adults with dementia: difficulties and challenges, Age and Ageing, Volume 51, Issue 12, December 2022, afac254, https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afac254

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

As the main source of informal care in China, family members bear a tremendous caregiving burden, particularly in relation to older people with dementia (PwDs). However, the continuous caregiving trajectory of family caregivers was unclear.

To investigate the trajectory of PwDs’ family caregivers’ struggles from home care to institutional care, and identify the common tipping points leading to institutional care from their perspectives.

An ethnographic study was conducted in a long-term care institution in Chengdu, China, from 2019 to 2020. Face-to-face, semi-structured interviews were carried out with 13 family members (i.e. 5 spouses and 8 adult children) of older PwDs during family caregivers’ visits. The interviews were recorded and transcribed, after which the transcripts were analysed using thematic analysis.

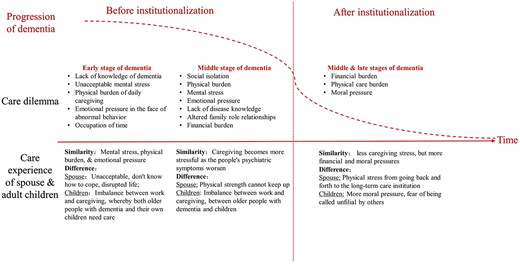

The family caregivers’ experiences before and after the PwDs’ institutionalization fell into two distinctive parts, and three subthemes about their caregiving experiences in each period were identified: the mental stress, the physical care burden, and the social and emotional pressure connected to home-based care; the moral pressure and emotional torment, the financial burden, and new worries after institutionalization. The tipping points in between the two stages were major changes or incidents related to the PwDs’ status. Variations in the spouse and older children’s care experiences also emerged.

Our study provides a nuanced analysis of the trajectory of family caregiving for PwDs. The plight of family caregivers at all stages should be recognized and supported with adequate medical and social resources, with a further consideration of the caregivers’ relationships with the older PwDs.

Key Points

Family caregivers of dementia people bear a tremendous caregiving burden, but the continuous caregiving trajectory is unclear.

Mental stress, physical care burden and social and emotional pressure are the main struggles at the home care stage.

Moral pressure and emotional torment, financial burden and new worries are the main struggles after institutionalization.

The tipping points in between the two stages are major changes or incidents related to the people’s status.

Adequate medical and social resources are vital to support family caregivers of people with dementia.

Introduction

It is estimated that there are 15.07 million people with dementia (PwDs) in China, accounting for 6% of all older adults aged 60+ [1]. The total annual socioeconomic cost of PwDs was estimated to be $167.74 billion in 2015, 1.3-fold than the world average [2]. Over half of these total socioeconomic costs were indirect costs associated with informal caregiving [2]. Informal caregiving can cause monetary losses due to a reduction in caregivers’ income, an imbalance between work and caregiving, and unexpected injuries [3].

Family is the main source of informal caregiving in China [4]. Previous studies revealed that over 96% of PwDs were cared for at home by their spouse and/or adult children [5]. Limited by their knowledge and skills about dementia care and a lack of external help, family caregivers struggle to fulfil their daily care responsibilities, which increase exponentially as the dementia condition progresses [6]. A nationwide online survey on the Alzheimer’s disease (AD) family caregiving burden showed that 68% of caregivers suffered from insufficient sleep, and over 74% complained about psychosocial problems due to their never-ending care duties [7]. Moreover, previous studies noted that the majority of these caregivers were older adults, with several chronic health conditions themselves [5, 8]. The dual role of caregiving and self-care may burden the caregivers physically and mentally, to the extent that they have to resort to professional care.

Less is known about the continuous caregiving experience of family caregivers of PwDs from home-based care to institutional care. One recent Chinese study reported stressors and the coping strategies of the adult children of PwDs in long-term care facilities, while the care experiences of the PwDs’ spouses need further investigation [9]. Although long-term care insurance (LTCI) has been piloted in China since 2016, the health workforce shortage, poor quality assurance and disengagement between health and social care services remain of concern [10]. In a collectivistic culture endorsing filial duty and family-centredness, the transition from family-based to institutional care may further involve conflicts between the family and the care recipients, as well as moral questions within the caregivers themselves [11–13].

Considering the Chinese government’s ‘9073’ or ‘9064’ older adults care framework (i.e. 90% of older adults depend on family care, 6–7% on community care and 3–4% on institutional care), it is necessary to understand families’ care trajectories over the transition process and the barriers they encountered in different care settings. Using a retrospective design, this ethnographic study investigated the trajectory of family caregivers’ struggles from family-based care to institutional care and identified the common tipping points leading to the transition to institutional care from the caregivers’ perspectives.

Methods

Study site and sample

The study was conducted in a long-term care institution in Chengdu, China, from 2019 to 2020. Chengdu city has 16.9% of its population aged over 65, 1.25 times than the national average [14]. Responding to its fast aging population, Chengdu is among one of the first-round 15 piloting cities of LTCI and has been enhancing its healthcare systems, including integrated medical and social care services. The studied institution was one such integrated healthcare facility, affiliated to a local public hospital specializing in geriatrics.

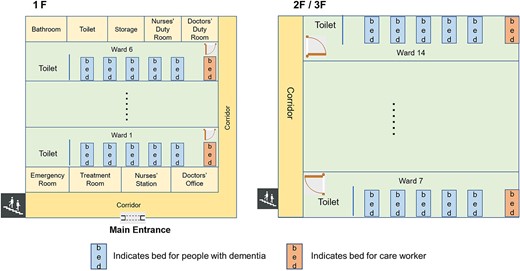

The long-term care institution is a three-floor building (Figure 1 for the floor map). There were 108 residents including 79 PwDs, cared for by 6 doctors, 21 nurses and 22 care workers. The PwDs’ family caregivers constituted our study sample. They were approached when visiting the PwDs at the institution. The family caregivers were recruited if they (i) had a relative diagnosed with dementia before entering the institution; (ii) were the main caregivers of PwDs during home care (often continually participating in PwD’s care after institutionalization) and (iii) agreed to participate in this study. Ethical approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board of Sun Yat-sen University (IRB Approval no. 2019-124), and informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Data collection

The researcher (H.L.) stayed in the institution full time as other staff for over 14 months, interviewed family caregivers and staff members, and observed and recorded all aspects of the institution’s work and the interaction among staff, PwDs, and their families. For this research, we specifically interviewed the family members when they came to visit. Altogether, we conducted semi-structured interviews with 13 family caregivers of PwDs. The retrospective interviews ranged from 30 min to one and a half hours, focusing on the family caregivers’ long-term experiences of caring for older PwDs at home and in institutions. Specifically, the interviews focused on: (i) how the family took care of the PwD at home and the difficulties encountered; (ii) why they chose institutional care and in what circumstances the PwD were sent to the care institution and (iii) how the family caregivers felt and what they did after sending the PwDs into institutional care. The regular family visits were interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. For updates regarding the family’s care practice over this period, the researcher spoke to the doctors, nurses and care workers who provided care to the PwDs of the 13 families. Reflective field notes were taken to supplement the formal interviews.

Data analysis

The interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were analysed using thematic analysis [15]. The first two authors (J.T. and H.L.) analysed the data to identify the themes. They read and re-read all of the transcripts to familiarize themselves with the data, then coded the data independently to generate the initial codes and searched for themes based on these. The two authors then reviewed the themes identified. When differences arose, the research team discussed these to achieve consensus. Verbatim quotations were presented to provide support for the findings. Besides the interview data, the study benefited from the long-term fieldwork, which enriched our understanding of the institutional context and supplemented the interviews. The observation notes taken during the fieldwork served as a ‘triangulation’ [16] to increase the credibility and validity of the findings.

Results

The characteristics of the family caregivers and PwDs

Table 1 shows the main characteristics of the family caregivers and PwDs. The family caregivers were mainly the PwDs’ spouses (38%) and adult children (62%), with 10 out of 13 being female (4 wives, 6 daughters), an average age of 62.6 and a duration of providing care from <1 month to 5 years. The PwDs had an average age of 81, all had multimorbidity and nearly half were female and widowed. They all had medical insurance and six were further supported by LTCI.

The characteristics of family caregivers and people with dementia in this study

| Number . | Family caregivers . | Home care length (year) . | People with dementia . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Interviewee . | Gender . | Age (year) . | Work status . | Gender . | Age (year) . | Marital status . | Disease status . | Medical insurance . | LTCI . | |

| 1 | Wife | F | 70 | Retired | 0.58 | M | 70 | Married | AD and multimorbidity | UEBMI* | NO |

| 2 | Wife | F | 82 | Retired | 2 | M | 84 | Married | AD and multimorbidity | UEBMI | YES |

| 3 | Daughter | F | 55 | Unemployed | 3 | M | 80 | Married | AD and multimorbidity | UEBMI | NO |

| 4 | Daughter | F | 70 | Retired | 0.5 | F | 88 | Widowed | MCI and multimorbidity | UEBMI | NO |

| 5 | Daughter | F | 44 | Housewife | 2 | M | 79 | Widowed | Mixed dementia and multimorbidity | UEBMI | YES |

| 6 | Wife | F | 62 | Retired | 0.5 | M | 75 | Married | MCI and multimorbidity | URBMI | YES |

| 7 | Daughter | F | 53 | Employee | 0.16 | F | 93 | Widowed | AD and multimorbidity | UEBMI | NO |

| 8 | Husband | M | 80 | Retired | 5 | F | 79 | Married | ad and multimorbidity | UEBMI | YES |

| 9 | Daughter | F | 54 | Employee | 1 | M | 79 | Widowed | AD and multimorbidity | UEBMI | NO |

| 10 | Wife | F | 75 | Retired | 0.5 | M | 79 | Married | Vascular dementia and multimorbidity | UEBMI | YES |

| 11 | Son | M | 55 | Employee | 0.08 | F | 85 | Married | AD and multimorbidity | UEBMI | NO |

| 12 | Son | M | 61 | Retired | 0.5 | F | 87 | Widowed | AD and multimorbidity | UEBMI | NO |

| 13 | Daughter | F | 53 | Employee | 0.5 | F | 81 | Widowed | Mixed dementia and multimorbidity | UEBMI | YES |

| Number . | Family caregivers . | Home care length (year) . | People with dementia . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Interviewee . | Gender . | Age (year) . | Work status . | Gender . | Age (year) . | Marital status . | Disease status . | Medical insurance . | LTCI . | |

| 1 | Wife | F | 70 | Retired | 0.58 | M | 70 | Married | AD and multimorbidity | UEBMI* | NO |

| 2 | Wife | F | 82 | Retired | 2 | M | 84 | Married | AD and multimorbidity | UEBMI | YES |

| 3 | Daughter | F | 55 | Unemployed | 3 | M | 80 | Married | AD and multimorbidity | UEBMI | NO |

| 4 | Daughter | F | 70 | Retired | 0.5 | F | 88 | Widowed | MCI and multimorbidity | UEBMI | NO |

| 5 | Daughter | F | 44 | Housewife | 2 | M | 79 | Widowed | Mixed dementia and multimorbidity | UEBMI | YES |

| 6 | Wife | F | 62 | Retired | 0.5 | M | 75 | Married | MCI and multimorbidity | URBMI | YES |

| 7 | Daughter | F | 53 | Employee | 0.16 | F | 93 | Widowed | AD and multimorbidity | UEBMI | NO |

| 8 | Husband | M | 80 | Retired | 5 | F | 79 | Married | ad and multimorbidity | UEBMI | YES |

| 9 | Daughter | F | 54 | Employee | 1 | M | 79 | Widowed | AD and multimorbidity | UEBMI | NO |

| 10 | Wife | F | 75 | Retired | 0.5 | M | 79 | Married | Vascular dementia and multimorbidity | UEBMI | YES |

| 11 | Son | M | 55 | Employee | 0.08 | F | 85 | Married | AD and multimorbidity | UEBMI | NO |

| 12 | Son | M | 61 | Retired | 0.5 | F | 87 | Widowed | AD and multimorbidity | UEBMI | NO |

| 13 | Daughter | F | 53 | Employee | 0.5 | F | 81 | Widowed | Mixed dementia and multimorbidity | UEBMI | YES |

F, female; M, male; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; MCI, moderate cognitive impairment; UEBMI, urban employee basic medical insurance; URBMI, urban resident basic medical insurance.

*indicates not local.

The characteristics of family caregivers and people with dementia in this study

| Number . | Family caregivers . | Home care length (year) . | People with dementia . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Interviewee . | Gender . | Age (year) . | Work status . | Gender . | Age (year) . | Marital status . | Disease status . | Medical insurance . | LTCI . | |

| 1 | Wife | F | 70 | Retired | 0.58 | M | 70 | Married | AD and multimorbidity | UEBMI* | NO |

| 2 | Wife | F | 82 | Retired | 2 | M | 84 | Married | AD and multimorbidity | UEBMI | YES |

| 3 | Daughter | F | 55 | Unemployed | 3 | M | 80 | Married | AD and multimorbidity | UEBMI | NO |

| 4 | Daughter | F | 70 | Retired | 0.5 | F | 88 | Widowed | MCI and multimorbidity | UEBMI | NO |

| 5 | Daughter | F | 44 | Housewife | 2 | M | 79 | Widowed | Mixed dementia and multimorbidity | UEBMI | YES |

| 6 | Wife | F | 62 | Retired | 0.5 | M | 75 | Married | MCI and multimorbidity | URBMI | YES |

| 7 | Daughter | F | 53 | Employee | 0.16 | F | 93 | Widowed | AD and multimorbidity | UEBMI | NO |

| 8 | Husband | M | 80 | Retired | 5 | F | 79 | Married | ad and multimorbidity | UEBMI | YES |

| 9 | Daughter | F | 54 | Employee | 1 | M | 79 | Widowed | AD and multimorbidity | UEBMI | NO |

| 10 | Wife | F | 75 | Retired | 0.5 | M | 79 | Married | Vascular dementia and multimorbidity | UEBMI | YES |

| 11 | Son | M | 55 | Employee | 0.08 | F | 85 | Married | AD and multimorbidity | UEBMI | NO |

| 12 | Son | M | 61 | Retired | 0.5 | F | 87 | Widowed | AD and multimorbidity | UEBMI | NO |

| 13 | Daughter | F | 53 | Employee | 0.5 | F | 81 | Widowed | Mixed dementia and multimorbidity | UEBMI | YES |

| Number . | Family caregivers . | Home care length (year) . | People with dementia . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Interviewee . | Gender . | Age (year) . | Work status . | Gender . | Age (year) . | Marital status . | Disease status . | Medical insurance . | LTCI . | |

| 1 | Wife | F | 70 | Retired | 0.58 | M | 70 | Married | AD and multimorbidity | UEBMI* | NO |

| 2 | Wife | F | 82 | Retired | 2 | M | 84 | Married | AD and multimorbidity | UEBMI | YES |

| 3 | Daughter | F | 55 | Unemployed | 3 | M | 80 | Married | AD and multimorbidity | UEBMI | NO |

| 4 | Daughter | F | 70 | Retired | 0.5 | F | 88 | Widowed | MCI and multimorbidity | UEBMI | NO |

| 5 | Daughter | F | 44 | Housewife | 2 | M | 79 | Widowed | Mixed dementia and multimorbidity | UEBMI | YES |

| 6 | Wife | F | 62 | Retired | 0.5 | M | 75 | Married | MCI and multimorbidity | URBMI | YES |

| 7 | Daughter | F | 53 | Employee | 0.16 | F | 93 | Widowed | AD and multimorbidity | UEBMI | NO |

| 8 | Husband | M | 80 | Retired | 5 | F | 79 | Married | ad and multimorbidity | UEBMI | YES |

| 9 | Daughter | F | 54 | Employee | 1 | M | 79 | Widowed | AD and multimorbidity | UEBMI | NO |

| 10 | Wife | F | 75 | Retired | 0.5 | M | 79 | Married | Vascular dementia and multimorbidity | UEBMI | YES |

| 11 | Son | M | 55 | Employee | 0.08 | F | 85 | Married | AD and multimorbidity | UEBMI | NO |

| 12 | Son | M | 61 | Retired | 0.5 | F | 87 | Widowed | AD and multimorbidity | UEBMI | NO |

| 13 | Daughter | F | 53 | Employee | 0.5 | F | 81 | Widowed | Mixed dementia and multimorbidity | UEBMI | YES |

F, female; M, male; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; MCI, moderate cognitive impairment; UEBMI, urban employee basic medical insurance; URBMI, urban resident basic medical insurance.

*indicates not local.

Difficulties associated with home-based care

Our interviewees reflected that they cared for their relatives at the early stage of their dementia. As the dementia progressed, they started to face an increasing number of challenges, which can be grouped into mental stress, physical burden and social and emotional pressure.

Mental stress: lacking knowledge, feeling guilty and uncertain

Many of the interviewees indicated that they lacked knowledge about dementia. They would accept the early symptoms of dementia, such as becoming forgetful or emotional, as part of the natural aging process or due to the change in lifestyle after retirement. Later, when these symptoms become more frequent, they might be mistaken for ‘poor memory’, ‘emotions’ or ‘anxiety’. Largely being ignored, leading to a delayed diagnosis, many of the family caregivers felt a sense of guilt and self-blame for not seeking treatment for their loved ones sooner.

At the beginning, he often got lost on his way home, I ignored this, thinking it was due to the poor memory many old people have. . . For years, we didn’t try any medication and it deteriorated fast. By 2018, we felt it was really serious and visited the hospital. The doctor gave him many drugs, but he did not take them regularly. I thought too many drugs would hurt his body, so didn’t push him. . . Now, I regret this often, always wondering if I did anything wrong that led to his rapid deterioration. (P2’s wife, 82 years old)

They were also unaware of how to take care of their relatives with dementia, particularly how to handle the neuropsychiatric and behavioural symptoms that arose as the dementia progressed. They had to be on the alert all the time, as PwDs may become delirious unpredictably, wander off and get lost at any time. The PwDs’ increasing neuropsychiatric and behavioural symptoms made the family caregivers feel frustrated.

There was one time I had to go shopping, and told her to stay at home but, later, she went out by herself, and became disoriented on the way, getting lost. The whole family went out, searching for her. It scared us. Even if I took her with me when I went shopping, she might get lost while I made the payment. Later, we hired a carer to attend to her 24 hours, but there were other incidents. She suffered several falls when walking with the carer, and we had to send her to hospital repeatedly. . .Exhausted! (P13’s daughter, 53 years old)

Physical burden: an unbearable care burden over time

The respondents reflected that, during the early stage of dementia care, they were still able to handle the caregiving responsibility and try to seek a balance with their family life. The care work mainly involved assisting with household tasks, self-care tasks and mobility but, as the illness progressed, the PwDs’ ability to perform their daily life activities reduced significantly, leading to them needing more help and even 24-hour assistance. The disturbed sleep associated with dementia further changed the lives of the caregivers. The care burden was especially heavy when there was only one helper available, who might need support themselves.

When my mum had symptoms, she didn’t sleep at night, tore the quilt apart. . . At the beginning, I stayed by her side, not sleeping either but, after a few nights, I felt dizzy and weak, unable to control my moods. . . I never got a good night’s sleep since her illness began, had to get up at night several times to help her. Now my hands have tenosynovitis. My mum gave birth to me when she was 18. Now, I am over 70 years old. If it continued like this, I would go to hospital too. . . (PwD 4′ daughter, 70 years old).

Furthermore, all 13 of the PwDs had multi-morbidities, which led to the necessity for regular hospital visits. The caregivers had to take them to visit the hospital regularly for physical checkups, medication and various symptom control. This created a further physical and financial burden for the family caregivers, particularly the spouses.

Ever since she fell sick, I took care of her. At the beginning, it was OK. Later, she had much sputum and needed suction. We couldn’t do suction at home, we had to send her to hospital. Suction would make her feel better for a few days, but gradually we visited hospital more and more frequently. It was exhausting to visit hospital one day or another. I began to look for an institution to take care of her. (P8’s husband, 80 years old)

Social and emotional pressure: social isolation, changed life and family relationships

In addition to the mental and physical care burden, the behavioural and psychological symptoms associated with dementia, such as agitation and aggression, further strained the family relationships. Aggressive behaviours, whether verbal or physical, emotionally harmed the family caregivers, who felt that their loved one had turned into a stranger.

When he became agitated, he’d beat me with his fist. One day, I asked him who I was, and he suddenly slapped my face. It was painful and my face was bruised. We always had a very good relationship. I never thought he’d hit me one day (crying). . . (P2’s wife, 82 years old)

Sometimes, my father didn’t recognize me. I knew he must feel puzzled about not knowing the people around him. He couldn’t even tell what was edible. He’d put all kinds of stuff in his mouth. Watching him, I felt terrible. I had to treat him like a child, teaching him what was edible and inedible anew but his symptoms were unstable. Sometimes, he got angry if I treated him like a small kid, and would even hit me. (P3’s daughter, 55 years old)

The family caregivers reported becoming the ‘parent’ of the PwDs and treating them like a child. In a culture that values family harmony, the changed family roles and relationships posed a great emotional burden on the caregiver and sparked conflicts. The long hours required to fulfil the caring role also made the family caregivers socially isolated, particularly when they were the sole caregiver, who had to devote all of their energy and time to caregiving and were bound within the domestic space. For the older spouses, caregiving proved an unbearable physical burden and disrupted their social life while, for the adult offspring, caregiving created difficulties related to balancing caregiving, work and other family obligations.

Since he fell sick, I have to be around 24 hours. Once he left the house, when I was cooking, I couldn’t find him anywhere and called the police. From then on, I always kept an eye on him. . . I used to enjoy my life after retiring, went out with my friends often but, because of his illness, I couldn’t go anywhere. (P2’s wife, 82 years old)

In the first two years since my father’s diagnosis, I had to run from here to there every day: my father’s home, the hospital, my home. . . I was too busy to handle all this. I cooked food, fed him, cleaned the house, finished all this and was about to return to my own home to take care of my son, and he made everything a mess again. . . I was desperate, and sometimes couldn’t help scolding him (crying). My father was unhappy too and deteriorated fast. Later, I simply quit my job. (P5’s daughter, 44 years old)

Tipping points: major incidents or changes in the older adults’ status

The duration from home-based care to institutionalization ranged from a month to 5 years for the 13 PwDs, with an average time of less than a year. Most of the family would do their best to take care of the PwD at home for as long as possible. In the process, they might engage in long deliberations about institutional placement when encountering care difficulties at home, but major incidents or changes in the PwDs’ status finally triggered the decision to transfer the individual to an institution. Among the family caregivers interviewed, the tipping points included: a deterioration in mental and cognitive status (n = 8, 61.5%), a diagnosis of compound diseases in addition to dementia (n = 4, 30.8%), one or more falls (n = 3, 23.1%) and an overall physical deterioration (n = 1, 7.7%).

She had falls, lying on her bed but with emotional disturbance, and would attack people. Later, she didn’t eat anything, was delirious, said bad words, hit the carer. . . (P7’s daughter, 53 years old)

These major changes in the PwDs’ physical and mental status led to increased medical and care needs that were beyond the family’s capacity to provide. Without sufficient support from the community, the family caregivers could only resort to institutional care, yet it was hard to find a suitable institution that could both provide quality care and meet the medical needs of the PwDs. For some families, institution placement was a repeated process. They tried to choose the best care institution for their relatives and might switch repeatedly between home and different institutions, before making their final choice.

I wanted to continue taking care of him but couldn’t handle it. He had several falls, but I couldn’t move him. After several falls, we finally decided to put him (in an institution). Other nursing homes do not provide good (medical) treatment. This institution (affiliated to a hospital) provides (medical) treatment, so we don’t need to worry. Care and treatment—both solved. (P2’s wife, 82 years old)

Family caregiving for PwDs after institutionalization

After being institutionalized, the family caregivers’ physical burden was reduced, but they continued to assist with PwD’s care. The moral pressure and emotional torment, financial burden, plus the new worries after institutionalization emerged as the main struggles at this stage.

Moral pressure and emotional torment

The family caregivers spoke of moral pressure after sending the PwD to an institution. The adult offspring feared being criticized as unfilial by those around them. Many reported experiencing a sense of guilt, especially at the beginning of the institution placement, when the PwDs had not yet adapted to their new environment and asked to return home. They had to persuade themselves that their decision was correct.

My sister and I had deliberated for a long time and overcame the social pressure to send my mum here (the long-term care institution). We’re afraid of being labelled unfilial, but couldn’t take good care of her back home. . . Here, the doctors, nurses, and care workers are all professional, and give her better care. What we do is to provide her with the best possible care. (P13’s daughter, 53 years old)

Institution placement was a stressful transition not only for the PwDs but also for their caregivers, especially for spouses. The family members mentioned feeling like they had lost their loved one after the institutional placement and paid regular visits to relieve their sense of loss and provide company.

When he was at home, I had something to do every day: cooking, taking care of him. . . I was busy with things to do. . . Then, he was sent to the institution, and I felt very uncomfortable and lonely. The hardest thing was accepting it emotionally. We had a very good relationships, had never quarrelled in all these years, but he was suddenly absent from my life. . . So, whenever I had time, I came to visit, and he was thrilled when I visited. (P6’s wife, 62 years old)

Financial burden: increased expenditure and insufficient insurance

One of the biggest pressures following institutionalization was the financial burden. While their physical burden was relieved, family had to spend more money to pay for the institution’s accommodation, medical bills and care workers. For most of the PwDs, the accommodation and medical bills were partially covered by their medical insurance, with the proportion varying based on the insurance type. For those with insurance outside the local city, the proportion covered was much lower compared to that for the PwDs with local insurance. The cost of care workers (2,000 to over 5,000 yuan/month, depending on the PwD’s care needs) could also be compensated by LTCI, but only local residents who had medical insurance in Chengdu were entitled to LTCI. Among the 13 PwDs, only 6 were supported by LTCI.

The expenses here are partly reimbursed by the insurance, but only the medical expenses (are covered). Others still have to be paid out of our own pocket. Besides, after coming here, my mother has to spend more on other items: nutrition supplements, incontinence pads, a blender (to make food easier to digest), etc. Also, it takes time, energy and money for me to go back and forth between my home and the institution. (P11’s son, 55 years old)

Our insurance is not based in Chengdu, so we have to send the bills back to our hometown for reimbursement (at a lower rate), and pay all of the care worker fees ourselves. . . Every month, he needs 6,000 to 7,000 yuan (out-of-pocket expenses). We don’t have a large pension. He gets just over 4,000 yuan a month, which is nowhere near enough. It adds to my mental stress. (P1’s wife, 70 years old)

Among our interviewees, for those PwDs with a stable condition, the monthly overall out-of-pocket payment was 5,000 to 6,000 yuan while, for those with various symptoms and worse conditions, the monthly out-of-pocket payment could rise to 10,000 yuan. On the other hand, these PwDs only had a pension ranging from 2,000 yuan to less than 8,000 yuan, which could hardly meet their overall expenses.

Worries: the quality of care and the challenges related to distance

Another reason for the family’s frequent visits was their concern about the quality of the care provided by the institution. During their visits, the family members made sure that the care workers understood the preferences and life habits of the PwDs. They brought various supplements and all personal necessities. They also brought food that the PwDs liked or desired, or home-cooked food that they believed to be more nutritious. They hoped that, through their efforts to assist with or supplement the institutional care, they could improve their loved one’s quality of life.

She (the care worker) said she had fed my father, but how could I tell? She took care of five PwDs at the same time, so how could she feed my father patiently? When I have time, I come to feed my father myself. (P3’s daughter, 55 years old)

The food at the institution isn’t nutritious enough. He (her father) can’t eat it, I have to send food (that he likes) myself. . . Sometimes, I buy fruit and milk to supplement his regular meals. (P9’s daughter, 54 years old)

Observation note sample

Family members often bring their own food to the institution, sometimes feeding the older adults in person. For family members, feeding the PwD a meal takes a long time, whereas they wait the PwD to chew and swallow the food then feeding another spoon. In contrast, care workers try to finish the feeding as soon as possible, often the PwD still has food within the month, while another spoon would be filled in. In each room, there are five PwDs and one allocated care worker, the care worker often runs from one bed to another to feed the PwDs, sometimes feeding two or three PwDs at the same time. Most care workers like tube feeding the most because they can finish a feeding within a few minutes.

However, sometimes it was challenging for the family members to continue to participate in the care of their relatives. Most of these care institutions were located in the suburbs so it was a long trip for the family members to visit, and especially challenging for the older spouses who were frail physically and relied on public transportation to get there. Many of the adult offspring could only visit at the weekends or during vacations. Some of the family members lived in another city, and so could not visit in person. When not visiting, the family continued to monitor the care at a distance through making regular video calls to their relatives and maintaining contact with the institution’s staff.

My physical condition is poor. I live in Hainan (another province) most of the time. Our (adult) kids are not in Chengdu, and she (his wife) resides here. The family (members) are separated, unable to visit her. Luckily, her care worker is responsible. (With the care worker’s aid), I call her (his wife) through a video (chat) every day. (P8’s husband, 80 years old)

I’ve visited him for five years. In the past, I came quite often. Now, with the pandemic, it’s too complex for me (to confirm a negative Covid test) to enter (the institution). . . (P10’s wife, 75 years old)

In the later stage of this research, due to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the care institution was closed to visitors for a long period. Even when it reopened to family visitors, the visiting procedure was more complex, with proof of a negative COVID test required, which reduced the frequency of the family visits. The recent visitor restrictions caused some families’ worries to increase substantially and again forced some PwDs with a stable condition to move back home. Among the 13 families whom we followed, one family transferred their relative out of the institution during the pandemic.

Findings above are summarized in Figure 2.

Discussion

Our study revealed that family caregiving for the PwDs is a continuous process, associated with the deterioration of dementia, with the caregiving experiences before and after institutionalization falling into two distinctive parts. The struggles during the early stage of dementia care are mainly due to a lack of knowledge and psychological stress. Then, the main burden during the middle stage of dementia care becomes the heavy physical stress, social isolation and strained family relationships, as the condition of the PwD worsens while the formal care support in the community is insufficient. Due to the unbearable physical and mental burden or incidents such as the PwDs’ falls, the family caregivers finally resorted to institutional care, whereby the struggles were mainly related to moral pressure and the financial burden. The challenges encountered further varied by the family caregivers’ relationship to the PwDs. Our findings well reflected the three stages of making the PwDs’ long-term institutional placement decisions, namely recognizing need, grappling with decision and evaluating outcomes, identified in a recent review [13]. We further enrich the literature by illustrating the continuum of dementia care struggles experienced by the same group of caregivers in the Chinese context.

The trajectory of family caregiving for older adults with dementia before and after institutionalization.

Our interviews indicated that home-based care for the PwDs was associated with a substantial mental and physical burden, mainly due to a lack of knowledge and the insufficient formal care support. The lack of knowledge leads to a low awareness and delayed detection of dementia. A nationwide survey showed that 38% of the PwDs and 42% of the family members believed that memory loss is a natural aging process and that there is no need for treatment. What’s worse, once diagnosed, the PwDs are more likely to be in the late stage of dementia [17] with increased neuropsychiatric and behavioural symptoms. Faced with the PwDs’ unstable and unpredictable status, the family caregivers often felt frustrated and in need of professional support, but the home and community-based formal care support are limited in China [18]. The day care centre or respite services at the community level do not function well [19,20], and the community healthcare centres rarely provide home visits [21]. Without formal care services or sufficient medical support at home, the family caregivers had to watch over the PwDs constantly, even 24 hours a day, with disrupted sleep. Caregiving thus significantly impacts the adult children’s work and life [22], while challenging for the older spouse to cope physically.

Despite being in a collectivistic culture valuing family obligations and filial piety, the long-term, intensive caregiving tore family relationships apart. Our respondents described the emotional pressure and frequent conflicts with the PwDs. Similarly, it was reported that 74% of the caregivers wanted to change their current state of life [7]. The spouse and adult children are the two main sources of informal care in China [23] yet, as clearly indicated by our study, adult children can also be considered ‘older adults’, who were in their 60s and need support themselves, let alone the PwDs’ spouses, who were the contemporaries of those for whom they cared. The situation becomes even more salient when the care burden cannot be shared between family members. Due to the prior family planning policy, most current Chinese families have a 4 + 2 + 1 structure, namely, a middle-aged couple with four older parents and at least one child, which places a care burden on the middle generation from both sides. Aging and no alternatives for the family caregivers made home-based care hard to sustain.

In addition to these struggles, major incidents or changes in the PwDs’ status triggered the institutionalization. Our results show that the first two reasons for the institutional placement of the PwDs are a deterioration in mental and/or cognitive status, and multimorbidity, in line with previous studies [24]. Furthermore, fall incidences count for another 23% of the institutionalizations, similar as a Hong Kong-based study that found nearly 1/5 of the PwDs were institutionalized after falls [25]. All of these conditions led to increased medical care needs of the PwDs that were beyond the family’s care capacity. The length of home care revealed here was shorter than that found in the previous literature [26], which may result from aforementioned delayed diagnosis of dementia, heavy caregiver burden and insufficient formal care support for the family caregivers.

Nonetheless, sending the PwDs to an institution does not mean the end of caregiving but another phase of moral and financial struggle. All of our interviewees described great moral pressure and emotional torment after the PwDs were institutionalized, similar to prior findings [13,27]. Influenced by Chinese culture, which emphasizes family obligations and filial piety, the family members are expected to care for their sick relatives at home, and institutional care is stigmatized [9, 11]. Accordingly, the caregivers who were the adult offspring of the PwDs feared social criticism, while the PwDs’ spouses felt uncomfortable about the absence of their loved ones [28]. With the moral and emotional attachment, the family members felt responsible for monitoring and evaluating the quality of care provided for the PwDs, participating in the care and making themselves useful after the institution placement.

Additionally, the financial burden became more prominent after institutionalization. As suggested by a prior study, the cost of weekly care increased by 115% after institutionalization compared to home-based care [29]. Besides the food and daily necessities required during home-based care, the family had to pay extra fees, such as for the institution’s accommodation. Previous studies have shown that PwDs who are placed in a care institution are often unable to perform activities of daily living independently or easily became disoriented, requiring a higher level of care and, therefore, a higher cost of care [9]. For most of the PwDs, the accommodation and medical bills are covered by the medical insurance but varied by its type, and only local residents are entitled to apply for LTCI [30,31]. Those expenses amounted to monthly out-of-pocket expenses ranging from 5,000 to 10,000 yuan for our interviewees, which can hardly be covered by the PwDs’ pension alone. Hence, the financial burden is particularly salient for those PwDs with small pensions and those coming from areas outside Chengdu, who had a lower medical insurance reimbursement and no entitlement to local LTCI.

Implications for practice and policy

The family caregiving trajectory is a long process, which continues even after the PwDs are institutionalized. Family caregivers play a pivotal role in the PwDs’ care, and the substantial physical, mental and financial care burden they endure should be properly addressed. Across the 24 LTCI piloting cities in China, only four, namely Qingdao, Shanghai, Chengdu and Guangzhou, addressed the care needs of PwDs [32]. These cities upgraded the LTCI level of these with dementia, provide service support or early intervention [33,34] and directly subsidy the family caregivers [35]. To assist these informal caregivers, Guangzhou additionally runs free caregiving training sessions and certifies those who qualify [36]. Given the shortage of formal caregivers, financial and training support may be particularly important to keep family caregivers actively and meaningfully engaged. Moreover, the design of a holistic, family-centred care program for both the PwDs and their family members is urgently needed, to strengthen the family ties and fulfil the psychological care needs of these caregivers [37].

Strength and limitations

The strength of the study is its nuanced analysis of the caregiving experience of family caregivers of PwDs from home-based care to institutional care, supplied by in-depth interview data and observation notes from the long-term field study. The interviewees include both spouses and adult children of the PwDs, to obtain a comprehensive picture of family caregivers’ dilemmas. Nevertheless, several limitations should be noted. First, our study used purposive sampling in a single institution in Chengdu. The interviewees are likely to represent families who successfully sent their relatives to the institution, who might be relatively better-off than those who cannot afford institutional care. Second, our sample consists of individuals who continued to visit the PwDs after institutionalization, while the attitude of family members who rarely visited their relatives is unknown. Third, when it proved impossible to continue interviewing the family caregivers due to COVID-19, we updated the information about family caregivers by talking to the staff. Despite the different sources of information used, all of the interviews were conducted by the same researcher, which ensured the comparability of the information obtained.

Conclusions

Our ethnographic study, using a retrospective design provides a detailed description of the trajectory of family caregiving for the PwDs. Over the trajectory, the mental stress, physical burden and social isolation are the main barriers encountered during home-based care, while the financial burden and moral pressure increase significantly once the PwD got institutionalized. The plight of the family caregivers of PwDs at all stages should be recognized and supported with adequate medical and social resources.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all of the healthcare workers who helped to recruit the participants and organize the interviews.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board of Sun Yat-sen University (IRB Approval no. 2019-124), and informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Declaration of Conflicts of Interest

None.

Declaration of Sources of Funding

This study was supported by the National Science Foundation of China: Understanding and Addressing Health and Social Challenges for Ageing in the UK and China. UK-China Health and Social Challenges Ageing Project (UKCHASCAP): present and future burden of dementia, and policy responses (grant number 72061137003, ES/T014377/1). The funders had no role in the design of the study; collection, analysis and interpretation of the data; or writing of the manuscript. The interview information has been anonymized and can be applied to the author team if there is any research need.

Reference

Author notes

The first two authors are co-first authors of the article.

Comments