-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Hongting Ning, Dian Jiang, Yan Du, Xiaoyang Li, Hongyu Zhang, Linan Wu, Xi Chen, Weihong Wang, Jundan Huang, Hui Feng, Older adults’ experiences of implementing exergaming programs: a systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis, Age and Ageing, Volume 51, Issue 12, December 2022, afac251, https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afac251

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

this study sought to systematically review and synthesize qualitative data to explore older adult exergame experiences and perceptions.

a comprehensive search was conducted in seven databases from the earliest available date to May 2022. All qualitative and mixed-method studies available in English and explored exergame experiences in older adults were included. Tools from the Joanna Briggs Institute were used for data extraction and synthesis. Data were extracted using the Capability, Opportunity and Motivation Model of Behaviour (COM-B model) as a guide, and a pragmatic meta-aggregative approach was applied to synthesize the findings.

this systematic review identified 128 findings and aggregated 9 categories from the 10 qualitative research articles included, and three synthesized findings were: older adult capability, opportunities in the exergaming program and motivation in the exergaming program. Capability consisted of attitude toward exergames, age- or health-related impairments and exergame knowledge and skills. Opportunities included older adult-friendly exergame design and social influence. Motivation included self-efficacy, support, instruction and feedback, health benefits, as well as unpleasant exergaming experiences.

it is crucial to tailor the exergaming program to suit the older population. We identified barriers and facilitators of implementing exergaming in older adults and found most barriers are surmountable. The results of the current systematic review could provide evidence for the design and implementation of exergaming programs among older adults. The ConQual score of the synthesized findings was assessed as low. Dependability and credibility should be accounted for in future studies to increase confidence.

Key Points

Three themes identified in the systematic review are as follows: older adult capability, opportunities and motivation.

These themes might help identify factors for implementing effective exergaming programs.

We identified barriers and facilitators of implementing exergaming in older adults and found most barriers are surmountable

Introduction

Society is rapidly aging, and the percentage of older adults worldwide is estimated to double from 12 to 22% between 2015 and 2050 [1]. This trend will pose significant challenges to families, policymakers and the health care system [2]. Engaging in physical activity and exercise substantially and positively impact older adults’ physical and mental health, such as a reduced risk of chronic diseases, lower likelihood of cognitive decline and improved mental health [3, 4]. However, insufficient physical activity is widely acknowledged as a global public health concern, especially in the older adult population [3, 5]. Older adults are often physically inactive or have a sedentary lifestyle; common complaints associated with physical inactivity include but not limited to physical and cognitive function decline, perceived feelings of exhaustion, lack of social support and environmental barriers (e.g. poor access to transport, unsuitable weather and unavailability of exercise programs) [6, 7].

An increasing number of studies are focusing on harnessing the power of technology to promote physical activity engagement in older adults. These efforts contributed to the emergence of exergames that enable users to play interactive video games using physical exercise. Exergames, which combines exercise and videogames [8] and can make physical activity a more positive experience. Exergames can offer a safe, attractive and interactive environment to motivate the older adult population to participate in physical activity by combining motor and cognitive skills focusing on the outcome of movements and not the movement itself [9, 10]. Furthermore, exergaming offers both physical and cognitive training concurrently and promotes the interplay of physical and cognitive functions [11, 12].

Promoting older adult health and well-being through engagement in exergaming is a topic that has attracted increased attention [13, 14]. One of our previous systematic reviews confirmed that exergaming is an innovative tool for improving physical and cognitive function [15]. Findings from several empirical studies also indicated exergames provide health promotion opportunities among the older population (e.g. improve physical and cognitive functions, increase social interaction, and reduce loneliness and depression) [16, 17]. These aspects contribute to health, which is defined not only as the absence of disease but a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being [18].

The literature highlights that qualitative research is necessary to increase knowledge of health intervention components and the active mechanisms influencing implementation [19]. In addition, qualitative research is a desirable research design to gain in-depth insight into older adult perceptions of the facilitators and barriers relevant to their context [20]. Synthesis of published qualitative studies have been regarded as integrating research evidence to achieve new understandings of a chosen topic [21]. Due to the emergence of exergame use in older adults, synthesizing previous research to guide future practice is warranted. While studies examining the implementation of exergaming programs for older adults have been abundant, few systematic reviews synthesized the findings of older adult exergaming experiences and perceptions. To the best of our knowledge, there were only two systematic reviews in this field [22, 23]. One is a conference paper that includes qualitative and quantitative data [23], and the other is a protocol for a systematic review and thematic synthesis [22]. Furthermore, these two reviews only focus on virtual reality (VR), which can be defined as a fully computer-generated environment displayed through a head-mounted display [21]. The latest exergaming classification includes VR and Wii, hand-held controllers, physical movements captured by video cameras or weight-sensing platforms [15]. Accordingly, the purpose of the current review was to explore the existing qualitative research that investigated experiences and perspectives in exergaming programs, and the perceptions of the facilitators and barriers to implementing exergaming programs in older adults around the world. Synthesized study findings might play a vital role in informing the design, development and implementation of exergame interventions for older adults.

Methods

Research design

This systematic review of qualitative research was based on the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) meta-synthesis approach [24]. Findings from the included studies were categorized based on similarity of meaning. These categories were subjected to a meta-synthesis to produce a series of synthesis findings that can be used as a basis for evidence-based practice [25]. This method aims to create a new, integrative interpretation of qualitative research findings, which is more substantive and meaningful than individual investigations [26]. The systematic review protocol is registered with PROSPERO: CRD42021284073. The Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research (ENTREQ) was used to guide the report of this synthesis [20].

Search strategy

A systematic search strategy was developed in consultation with a medical librarian. Seven databases were searched: Medline, Embase, Cochrane Database, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Scopus and Web of Science. A three-step search strategy was adopted in this study. An initial limited search of Medline has been undertaken, followed by an analysis of the text words in the title and abstract, and the index terms used to describe the article. A second extensive search was conducted using all identified keywords and index terms. Lastly, the reference lists of retrieved articles were hand-searched to locate any additional studies not included in the database search results. Key initial terms included: old*, elder*, aging, aging, ‘60 years*’, senior*, exergam*, video games, active video gam*, virtual reality, serious gam*, qualitative research, qualitative methodology and interviews. The World Health Organization believes most countries characterize old age starting at 60 years and above, thus, the definition of the older adults in the current study are those aged 60 years or more [27]. Only studies published in the English language were included. Year of publication was not restricted. A preliminary search was performed in October 2021, and the final search was conducted in May 2022. The full search strategy is detailed in Appendix 1, available in Age and Ageing online.

Eligibility criteria and study selection

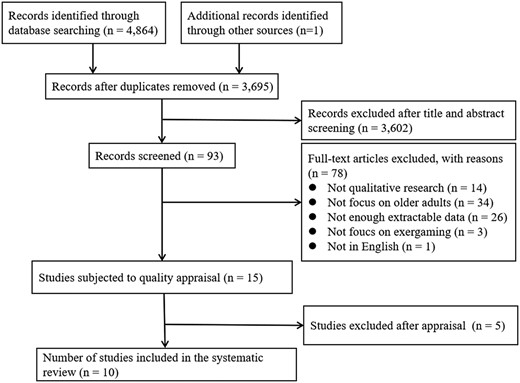

We focused on the experiences of older adults with exergame programs. Table 1 lists the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The search located 4,864 publications that were imported into Endnote X9 software. Endnote X9 and hand searching identified 1,170 duplicates, leaving 3,695 papers assessed by title and abstract relevance. The screening resulted in 93 articles meeting the selection criteria, and the full text of these articles was retrieved for further assessment. After reading the full text, 15 articles were eligible for quality appraisal. Search outcomes are presented in the PRISMA diagram (Figure 1). Two authors (HTN and DJ) independently undertook the screening process, and any disagreements about inclusion were resolved through recourse to a third author.

| Study aspect . | Inclusion criteria . | Exclusion criteria . |

|---|---|---|

| Design | Qualitative methodology or mixed methods | Quantitative studies and mixed-method studies with predominantly quantitative results |

| Aim/focus | Explored older adults’ experiences and perspectives regarding the implementation of exergaming programs. | Focused the experience and perspectives regarding the implementation of exergaming programs among family members, caregivers and physiotherapists |

| Article type | Peer-reviewed journal articles and conference papers with complete information. | Reviews, commentaries, editorials, theses, protocol, conference abstract and book chapters |

| Language | English | All other languages |

| Participants | Older adults (≥60 y). | Children, adolescents, middle-aged adults, or if unable to obtain age range |

| Evidence | Subjective accounts with at least one direct quote supporting the findings | Accounts based on recordings or researcher observations of consultations, or no direct quotes |

| Country | All countries |

| Study aspect . | Inclusion criteria . | Exclusion criteria . |

|---|---|---|

| Design | Qualitative methodology or mixed methods | Quantitative studies and mixed-method studies with predominantly quantitative results |

| Aim/focus | Explored older adults’ experiences and perspectives regarding the implementation of exergaming programs. | Focused the experience and perspectives regarding the implementation of exergaming programs among family members, caregivers and physiotherapists |

| Article type | Peer-reviewed journal articles and conference papers with complete information. | Reviews, commentaries, editorials, theses, protocol, conference abstract and book chapters |

| Language | English | All other languages |

| Participants | Older adults (≥60 y). | Children, adolescents, middle-aged adults, or if unable to obtain age range |

| Evidence | Subjective accounts with at least one direct quote supporting the findings | Accounts based on recordings or researcher observations of consultations, or no direct quotes |

| Country | All countries |

| Study aspect . | Inclusion criteria . | Exclusion criteria . |

|---|---|---|

| Design | Qualitative methodology or mixed methods | Quantitative studies and mixed-method studies with predominantly quantitative results |

| Aim/focus | Explored older adults’ experiences and perspectives regarding the implementation of exergaming programs. | Focused the experience and perspectives regarding the implementation of exergaming programs among family members, caregivers and physiotherapists |

| Article type | Peer-reviewed journal articles and conference papers with complete information. | Reviews, commentaries, editorials, theses, protocol, conference abstract and book chapters |

| Language | English | All other languages |

| Participants | Older adults (≥60 y). | Children, adolescents, middle-aged adults, or if unable to obtain age range |

| Evidence | Subjective accounts with at least one direct quote supporting the findings | Accounts based on recordings or researcher observations of consultations, or no direct quotes |

| Country | All countries |

| Study aspect . | Inclusion criteria . | Exclusion criteria . |

|---|---|---|

| Design | Qualitative methodology or mixed methods | Quantitative studies and mixed-method studies with predominantly quantitative results |

| Aim/focus | Explored older adults’ experiences and perspectives regarding the implementation of exergaming programs. | Focused the experience and perspectives regarding the implementation of exergaming programs among family members, caregivers and physiotherapists |

| Article type | Peer-reviewed journal articles and conference papers with complete information. | Reviews, commentaries, editorials, theses, protocol, conference abstract and book chapters |

| Language | English | All other languages |

| Participants | Older adults (≥60 y). | Children, adolescents, middle-aged adults, or if unable to obtain age range |

| Evidence | Subjective accounts with at least one direct quote supporting the findings | Accounts based on recordings or researcher observations of consultations, or no direct quotes |

| Country | All countries |

Quality assessment

The Joanna Briggs Institute Qualitative Assessment and Review Instrument (JBI-QARI) was used to critically appraise the research methodology rigour for each publication [28]. Questions answered as ‘yes’ scored 1, and those total scores of 5 or lower were considered low quality and excluded from the synthesis as similarly performed on previous studies [28, 29]. As a result of the quality appraisal process, five studies were excluded due to a lack of detail for the assessment of eligibility (Appendix 2 is available in Age and Ageing online), and ten papers were chosen for inclusion in the systematic review. Two reviewers (HTN and DJ) independently conducted the critical appraisal of each research synthesis selected. A lack of consensus was resolved through discussions between reviewers or assistance from a third reviewer on the team. Table 2 provides a quality assessment of the studies included in this review.

| Citation . | Q1 . | Q2 . | Q3 . | Q4 . | Q5 . | Q6 . | Q7 . | Q8 . | Q9 . | Q10 . | Score . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nawaz, A. et al. (2014) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | N | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Mol et al. [30] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Glännfjord F. et al. (2016) | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | N | Y | U | Y | 6 |

| Swinnen et al. [31] | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Meekes et al. [32] | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | 6 |

| Wollersheim et al. [33] | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Cruz et al. [34] | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Chao et al. (2015) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Jeremic et al. [35] | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | U | Y | U | Y | 6 |

| Rogers et al. (2021) | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Q1. Is there congruity between the stated philosophical perspective and the research methodology? | |||||||||||

| Q2. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the research question or objectives? | |||||||||||

| Q3. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the methods used to collect data? | |||||||||||

| Q4. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the representation and analysis of data? | |||||||||||

| Q5. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the interpretation of results? | |||||||||||

| Q6. Is there a statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically? | |||||||||||

| Q7. Is the influence of the researcher on the research, and vice-versa, addressed? | |||||||||||

| Q8. Are participants, and their voices, adequately represented? | |||||||||||

| Q9. Is the research ethical according to current criteria or, for recent studies, and is there evidence of ethical approval by an appropriate body? | |||||||||||

| Q10. Do the conclusions drawn in the research report flow from the analysis, or interpretation, of the data? | |||||||||||

| Citation . | Q1 . | Q2 . | Q3 . | Q4 . | Q5 . | Q6 . | Q7 . | Q8 . | Q9 . | Q10 . | Score . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nawaz, A. et al. (2014) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | N | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Mol et al. [30] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Glännfjord F. et al. (2016) | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | N | Y | U | Y | 6 |

| Swinnen et al. [31] | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Meekes et al. [32] | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | 6 |

| Wollersheim et al. [33] | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Cruz et al. [34] | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Chao et al. (2015) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Jeremic et al. [35] | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | U | Y | U | Y | 6 |

| Rogers et al. (2021) | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Q1. Is there congruity between the stated philosophical perspective and the research methodology? | |||||||||||

| Q2. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the research question or objectives? | |||||||||||

| Q3. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the methods used to collect data? | |||||||||||

| Q4. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the representation and analysis of data? | |||||||||||

| Q5. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the interpretation of results? | |||||||||||

| Q6. Is there a statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically? | |||||||||||

| Q7. Is the influence of the researcher on the research, and vice-versa, addressed? | |||||||||||

| Q8. Are participants, and their voices, adequately represented? | |||||||||||

| Q9. Is the research ethical according to current criteria or, for recent studies, and is there evidence of ethical approval by an appropriate body? | |||||||||||

| Q10. Do the conclusions drawn in the research report flow from the analysis, or interpretation, of the data? | |||||||||||

Y—Yes, N—No, U—Unclear.

| Citation . | Q1 . | Q2 . | Q3 . | Q4 . | Q5 . | Q6 . | Q7 . | Q8 . | Q9 . | Q10 . | Score . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nawaz, A. et al. (2014) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | N | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Mol et al. [30] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Glännfjord F. et al. (2016) | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | N | Y | U | Y | 6 |

| Swinnen et al. [31] | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Meekes et al. [32] | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | 6 |

| Wollersheim et al. [33] | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Cruz et al. [34] | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Chao et al. (2015) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Jeremic et al. [35] | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | U | Y | U | Y | 6 |

| Rogers et al. (2021) | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Q1. Is there congruity between the stated philosophical perspective and the research methodology? | |||||||||||

| Q2. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the research question or objectives? | |||||||||||

| Q3. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the methods used to collect data? | |||||||||||

| Q4. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the representation and analysis of data? | |||||||||||

| Q5. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the interpretation of results? | |||||||||||

| Q6. Is there a statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically? | |||||||||||

| Q7. Is the influence of the researcher on the research, and vice-versa, addressed? | |||||||||||

| Q8. Are participants, and their voices, adequately represented? | |||||||||||

| Q9. Is the research ethical according to current criteria or, for recent studies, and is there evidence of ethical approval by an appropriate body? | |||||||||||

| Q10. Do the conclusions drawn in the research report flow from the analysis, or interpretation, of the data? | |||||||||||

| Citation . | Q1 . | Q2 . | Q3 . | Q4 . | Q5 . | Q6 . | Q7 . | Q8 . | Q9 . | Q10 . | Score . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nawaz, A. et al. (2014) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | N | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Mol et al. [30] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Glännfjord F. et al. (2016) | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | N | Y | U | Y | 6 |

| Swinnen et al. [31] | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Meekes et al. [32] | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | 6 |

| Wollersheim et al. [33] | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Cruz et al. [34] | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Chao et al. (2015) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y | 8 |

| Jeremic et al. [35] | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | U | Y | U | Y | 6 |

| Rogers et al. (2021) | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | Y | 7 |

| Q1. Is there congruity between the stated philosophical perspective and the research methodology? | |||||||||||

| Q2. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the research question or objectives? | |||||||||||

| Q3. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the methods used to collect data? | |||||||||||

| Q4. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the representation and analysis of data? | |||||||||||

| Q5. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the interpretation of results? | |||||||||||

| Q6. Is there a statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically? | |||||||||||

| Q7. Is the influence of the researcher on the research, and vice-versa, addressed? | |||||||||||

| Q8. Are participants, and their voices, adequately represented? | |||||||||||

| Q9. Is the research ethical according to current criteria or, for recent studies, and is there evidence of ethical approval by an appropriate body? | |||||||||||

| Q10. Do the conclusions drawn in the research report flow from the analysis, or interpretation, of the data? | |||||||||||

Y—Yes, N—No, U—Unclear.

Data extraction and synthesis

The JBI-QARI standardized data extraction tool was used to extract data from the articles included in this review [36]. The first author extracted data from the 10 studies, including author and year, methodology, method, phenomena of interest, setting, geographical, cultural, participants, data analysis and author’s conclusion.

In addition, the reviewers carefully read the included articles and identified and extracted relevant study findings, including direct quotes, observations or statements that illustrate or support the findings from the primary studies. After all findings and illustrative data were extracted, two reviewers (HTN and DJ) independently appraised each finding and attributed a level of credibility to each finding. The levels of credibility were: unequivocal (U)—relates to findings beyond a reasonable doubt; credible (C)—relates to those findings that are interpretations, plausible in light of the data and theoretical framework and unsupported (Un)—the data do not support the findings. There were no disagreements regarding the credibility levels.

Data were extracted using the capability, opportunity and motivation model of Behaviour (COM-B model) as a guide. The COM-B model is one theory of behaviour that can contribute insights into exergame play behaviour [37]. COM-B posits behaviour as the result of three components: capability, opportunity and motivation. Capability comprises psychological (knowledge) or physical (skills); opportunity refers to social (societal influences) or physical (environmental resources); motivation can be reflective (beliefs, intentions) or automatic (emotion) [38]. In this ‘behaviour system’, capability, opportunity and motivation interact to generate behaviour as shown in Figure 2. This review utilized this model to understand the factors of capability, motivation and opportunity for older adult exergame program participation.

We aggregated the findings into different categories based on similarity of meanings; the categories were subjected to a meta-synthesis to generate synthesized findings by meta-aggregation [39]. The first author led the meta-synthesis process. The process was repeated when reviewing findings/categories/synthesized findings. In the presence of doubt, we consulted the original literature and conducted a group discussion to reach an agreement. We used the ConQual tool to evaluate confidence in the synthesized findings [40].

Findings

Characteristics of the studies

A total of 10 research studies were included in the review [30–35,41–44]. Of the papers, five were qualitative studies, and five were mixed-method studies with an analysis of qualitative data. All included articles were published between 2010 and 2021. Several methods were used in data collection, including semi-structured interviews, observations and focus group discussions. The sample size ranged from 8 to 31. Among the 10 studies, two were from the USA, and the other eight were from the UK, Australia, Canada, Belgium, Swedish, Brazil, Norway and South Africa, respectively. Detailed information about these studies is presented in Appendix 3, available in Age and Ageing online.

Meta-synthesis of qualitative data

A total of 128 findings were extracted from the ten included articles (Appendix 4 is available in Age and Ageing online): 102 unequivocal and 26 credible. These findings were aggregated into nine categories based on the similarity of meanings; these categories were meta-aggregated into three synthesized findings (Table 3). The results of the meta-synthesis are shown in Appendix 5, available in Age and Ageing online.

| Synthesized findings . | Category . | Nawaz et al. (2014) . | Mol et al. [30] . | Glännfjord et al. (2016) . | Swinnen et al. [31] . | Meekes et al. [32] . | Wollersheim et al. (2015) . | Cruz et al. [34] . | Chao et al. (2015) . | Jeremic et al. [35] . | Rogers et al. (2021) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Older adult capability | Attitudes toward exergaming | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Age- or health-related impairments to exergaming | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Exergame knowledge and skills | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Opportunities in the exergaming program | Older adult-friendly exergame design | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Social influence | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Motivation in the Exergaming program | Self-efficacy | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Support, instruction and feedback | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Health benefits | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Unpleasant experiences related to exergaming | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Synthesized findings . | Category . | Nawaz et al. (2014) . | Mol et al. [30] . | Glännfjord et al. (2016) . | Swinnen et al. [31] . | Meekes et al. [32] . | Wollersheim et al. (2015) . | Cruz et al. [34] . | Chao et al. (2015) . | Jeremic et al. [35] . | Rogers et al. (2021) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Older adult capability | Attitudes toward exergaming | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Age- or health-related impairments to exergaming | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Exergame knowledge and skills | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Opportunities in the exergaming program | Older adult-friendly exergame design | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Social influence | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Motivation in the Exergaming program | Self-efficacy | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Support, instruction and feedback | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Health benefits | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Unpleasant experiences related to exergaming | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Synthesized findings . | Category . | Nawaz et al. (2014) . | Mol et al. [30] . | Glännfjord et al. (2016) . | Swinnen et al. [31] . | Meekes et al. [32] . | Wollersheim et al. (2015) . | Cruz et al. [34] . | Chao et al. (2015) . | Jeremic et al. [35] . | Rogers et al. (2021) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Older adult capability | Attitudes toward exergaming | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Age- or health-related impairments to exergaming | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Exergame knowledge and skills | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Opportunities in the exergaming program | Older adult-friendly exergame design | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Social influence | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Motivation in the Exergaming program | Self-efficacy | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Support, instruction and feedback | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Health benefits | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Unpleasant experiences related to exergaming | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Synthesized findings . | Category . | Nawaz et al. (2014) . | Mol et al. [30] . | Glännfjord et al. (2016) . | Swinnen et al. [31] . | Meekes et al. [32] . | Wollersheim et al. (2015) . | Cruz et al. [34] . | Chao et al. (2015) . | Jeremic et al. [35] . | Rogers et al. (2021) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Older adult capability | Attitudes toward exergaming | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Age- or health-related impairments to exergaming | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Exergame knowledge and skills | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Opportunities in the exergaming program | Older adult-friendly exergame design | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Social influence | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Motivation in the Exergaming program | Self-efficacy | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Support, instruction and feedback | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Health benefits | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Unpleasant experiences related to exergaming | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Synthesized finding 1: older adult capability

It is important to recognize that older adult capability has a profound impact on implementing exergaming programs and participant experiences. Attitudes toward exergaming, age- or health-related impairments to exergaming participation, and exergame knowledge and skills are important factors of older adult capability.

Attitudes toward exergaming

Most older adults reported a positive attitude toward exergaming, but a small group of older adults were not interested in exergaming.

“I liked that it was a game. And you had to pay attention. Afterward, I felt better. It’s like sport to me. I feel the same after I do sports.”(Swinnen et al. [31] Belgium, p. 5).

“I don’t think I’ll play. (Why?) Well, it just doesn’t interest me. There’s no real interest.” (Jeremic et al. [35] Canada, p. 194).

Age- or health-related impairments to exergaming

Many older adults stated age- or health-related impairments limited their engagement in exergaming.

“At my age, it doesn’t function so well anymore.” (Swinnen et al. [31] Belgium, p. 6).

“I have arthritis ... have difficulty changing position.” (Chao, Y. Y. et al. US, 2015, p. 6).

“There are difficulties sometimes for me to exergaming, like tiredness, pain.” (Chao, Y. Y. et al. US, 2015, p. 6).

Exergame knowledge and skills

Older adults also expressed a lack of exergame knowledge and skills, indicating enough time to train and become familiarized is necessary.

“It (exergaming) annoyed me that I didn’t know it better.” (Cruz et al. [34] US, p. 6).

Some of the participants thought they might need more practicing time to improve their gaming skills: ‘No, because I didn’t do them that much, although they did improve while I was doing them. But if I had access to the machines all the time they would definitely go way up to what I did there for the first time. You just bring in the game and spend a… your real reaction to things’. (Jeremic et al. [35] Canada, p. 193).

Many older adults did not know how to perform the required stepping movements correctly. (Nawaz, A. et al. Norway, 2014, p. 583).

Older adults considered the exergames technology advanced and were concerned whether they could set-up and start the game on their own. (Nawaz, A. et al. Norway, 2014, p. 584).

Synthesized finding 2: opportunities in the exergaming program

It is crucial to identify relevant opportunities to participate in the exergaming programs. The impact of favourable opportunities can be related to older adult-friendly exergame design and social influence.

Older adult-friendly exergame design

Most existing exergames were initially designed for children or young adults, not many are specifically designed for older adults that takes potential barriers under consideration. Barriers include poor vision, physical function limitations and other health conditions that might hinder their abilities. Older adult-friendly exergame designs focused on a simplistic design and are suitable, usable, and acceptable for older adults would increase the exergame play opportunities for the older adult population.

“Well, my problem is my poor vision. Those things are presented on a flat surface and I don’t know if they’re there or here … and I get disgusted when I’m not able to retrieve one when I’ve been too far forward with it.” (Cruz et al. [34] US, p. 6).

“Participants believe that some adjustments of exergames should be made to match older adults’ physical function, e.g., appropriate difficulty and challenge.” (Jeremic et al. [35] Canada, p. 193).

“Reasons that made seniors dislike a game are usually difficulties they experience playing, such as a game being too complex or fast.” (Jeremic et al. [35] Canada, p. 189).

“Participants felt safe while exergaming because they were guided, and the pace and intensity of the exercises were adapted to older adults’ own abilities.” (Swinnen et al. [31] Belgium, p. 6).

“The tailored exergaming program was always adapted to the performance level of the older individual, you can adjust the speed yourself, by going faster or slower.” (Swinnen et al. [31] Belgium, p. 6).

Social influence

Social influence is concerned with the influence other people may have on older adult exergame participation [45]. Generally, participants viewed exergaming as a way to increase social connection opportunities through group play, thus making exercise more engaging and enjoyable. Some participants did not feel uncomfortable telling other people in their life about playing exergames, and some felt uncomfortable watched or judged by others while playing exergames.

“It would be fun to play with my grandchildren.” (Nawaz, A. et al. Norway, 2014, p. 583).

“If someone got a strike this often resulted in a lot of positive remarks from the group, and if many strikes were made in a row an even greater amount of cheers was given. If one participant played a poor series, the group would show their support. But they could still joke about the poor series with each other and have a good time.” (Glännfjord F. et al. Swedish, 2016, p. 5).

“Everything I do to move my body using exergame I’m not afraid to share.” (Nawaz, A. et al. Norway, 2014, p. 583).

“(When I participated in exergame play) I felt uncomfortable watched or judged by other people who were also in the room.” (Meekes et al. [32] UK, p. 5).

Synthesized finding 3: motivation in the exergaming program

Motivation is defined as the brain processes responsible for energizing and directing behaviour [46]. We found that older adult motivation for exergame engagement was mainly influenced by self-efficacy, support, instruction, and feedback, and health benefits, as well as unpleasant experiences related to exergaming.

Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy refers to an individual’s confidence in their ability to successfully perform a recommended health action [47]. Self-efficacy in relation to exergaming is based on the premise that exergame engagement may help participants gain confidence and induce feelings of pride and a sense of achievement, which may increase the motivation for exergame participation. Skills development was previously identified as a necessity for exergame participation. In addition, skills development might indirectly improve exergame performance by enhancing self-efficacy, as some participants reported an increase in confidence because they were able to develop new skills.

“To start undertaking the exergames was also experienced as a challenge that resulted in the participant feeling proud and a sense of achievement.” (Meekes et al. [32] UK, p. 5).

“Older people could also be assumed to have gained confidence in their cognition because they were able to do something new and develop new skills.” (Meekes et al. [32] UK, p. 6).

Support, instruction and feedback

Support, instruction and feedback may also increase older adult motivation to participate in exergames.

“Six older participants were also doubtful if they would be able to play the exergames on their own without the support of the physiotherapist.” (Meekes et al. [32] UK, p. 5).

“Seniors easily understood the concepts of exergames after the short demonstration by the test leader.” (Nawaz, A. et al. Norway, 2014, p. 583).

“I wonder, why did I miss it? Was I too slow, or was it that I miss-stepped on the squares?” (Nawaz, A. et al. Norway, 2014, p. 583).

Health benefits

Health benefits are facilitators to implementing exergaming programs. Many participants stated that exergaming improved their health status, which served as motivation to engage in the programs.

“My body felt much better, it (exergames) has made my arm stronger, and it gave me chance to exercise.” (Wollersheim et al. [33] Australia, p. 91).

“My memory has improved. I can remember things better than before.” (Swinnen et al. [31] Belgium, p. 4).

“It (exergames) gives me hope, it gives me cheer and it helps me to have a wonderful life, physically, health wise physically.” (Chao, Y. Y. et al. US, 2015, p. 5).

“If you get very interesting things like that (exergames), when you're in a lot of pain, you forget about the pain while you do it.” (Wollersheim et al. [33] Australia, p. 91).

Unpleasant experiences related to exergaming

Unpleasant experiences (e.g. tiredness, pain, fear of falling) related to exergaming were common barriers affecting participant motivation to engage with exergaming programs.

“My legs are not used to it, they get a little bit tired … more like itching a little, haha, they have to relax again.” (Swinnen et al. [31] Belgium, p. 5).

“There are difficulties sometimes for me to exercise, like tiredness, pain.” (Chao, Y. Y. et al. US, 2015, p. 6).

“My leg does not always support me. I am afraid to lose my balance.” (Chao et al. [43] US, p. 6).

To establish confidence in the evidence produced, the ConQual approach [40] was used to assess confidence in the synthesized findings. The ConQual summary of findings is shown in Appendix 6, available in Age and Ageing online.

Discussion

This is the first systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis to explore the experiences of older adults with exergaming programs. Ten qualitative studies on exergaming programs among older adults globally were included. This review systematically synthesized qualitative studies and contributed to new knowledge via the three themes: older adult capability, opportunities in the exergaming program and motivation in the exergaming programs. These themes indicate relevant factors that promote or hinder the implementation of exergaming programs among the older adult population and most of the barriers are surmountable. Synthesized findings are rarely reported in individual studies. This systematic review is timely, considering that exergaming is an innovative, fun and relatively safe way to exercise [48] and successful exergaming programs might become a promising approach for health promotion among older adults.

Older adult capability is one of the most critical factors affecting the successful implementation of an exergaming program

Most participants reflected a positive attitude toward exergames and reported the experience as new, challenging, fun and enjoyable. Previous qualitative studies also demonstrated an enjoyable experience for exergame participants [32,49]. These previous studies and this study confirm exergaming may be a promising tool to create enjoyment with physical exercise. However, it should be considered not everyone may be interested.

Participant capability to engage in exergaming was hindered by age- or health-related impairments, such as vision, hearing, motor skill and cognitive ability impairments. Previous studies support our finding that perceived poor health and impairments are frequently mentioned as barriers for older adult performance in physical activities [50, 51]. Therefore, we recommend taking participant impairments under consideration when designing and selecting an exergame (e.g. large font, simple menu, using a large screen, slow-moving images). In other words, successful implementation of an exergame intervention for the older adult population must be designed and developed specifically for this target group and must provide appropriate accommodations for impairments. [52]. This is supported by Schättin et al. [53], who highlighted that exergame design should consider participant physical, cognitive and mental conditions.

The findings of this review also suggest attention should be paid to participant knowledge and skills to improve capability. It should be noted most of the older adult population do not have exergaming experience and participants often considered the technology advanced, and concerns were raised regarding whether they could understand the rules and play correctly. Older adults need to be trained to improve exergame knowledge and skills, interventionists (exergame supervisors) should also be fully trained to provide sufficient support, instruction and feedback, thus increasing motivation. Training to improve knowledge and skills may improve direct or indirect exergame participation by increasing motivation.

Another synthesized finding identified in this review was the opportunities in the exergaming program

The findings in this review indicated that an older adult-friendly exergame design would increase the opportunity to participate. Most studies included using commercially available exergame systems, which were originally designed for teenagers and younger populations for entertainment [54]. Therefore, most of the existing exergames did not appear entirely suitable for older adults because of the lack of flexibility and adaptability to the requirements of this group. Older adults tend to have poor balance, visual impairments, muscle weakness and decreased confidence; therefore, exergames targeting this population may require special development [54]. To develop an older adult -friendly exergame, the following elements need to be considered: safe, implementation of familiar elements, great immersion, adaptation for individual difficulty levels, appropriate complexity, progressive increase of game intensity, better sound and image perception and content presentation in the local languages. The following elements should be avoided: negative auditory and visual feedback, content suitable only for younger populations, slow system response time and excessive complexity (‘fast and hard’).

This study also acknowledges the importance of social influence during exergame participation. It was clear that the social connection not only created opportunities to learn and interact with one another, but opened more opportunities for connection with peers and family members, especially grandchildren. These findings are consistent with the results in previous studies indicating social connection was a significant factor for increasing physical activity opportunities [55, 56]. Nevertheless, social influence might vary depending on cultural diversity and demographic background. For instance, studies conducted in Western culture countries (North American and Western European countries) [57] reflect an individualistic society, where individuals are less concerned about the opinions of others and are less likely to experience embarrassment for using exergames for physical activity [41]. However, older adults in Eastern cultures (East Asian countries such as China, Japan and Korea) tend to be more shy compared to their Western counterparts [58], and more likely to experience embarrassment for using exergames [59]. The feelings of being watched or judged by other people resulted in feelings of discomfort and may decrease opportunities for exergame participation.

A further synthesized finding identified in this review was the motivation in exergaming programs

Motivation can be defined as the driving force behind individual actions [60]. Research shows motivation is the most critical force for determining a desire for action [61], and in the context of exergame participation, self-efficacy is significant for maintaining motivation over time. Our findings suggest that participant self-efficacy increased after exergame activity. Schutzer and Graves [62] investigated the barriers and motivations to exercise in the older adult population and noted ‘self-efficacy is consistently identified as a crucial determinant of exercise behaviour in various populations and in many types of behavioural learning throughout the scientific literature’. Schutzer and Graves [63] also mentioned ‘the stronger one’s self-efficacy is, the more likely they will adopt and maintain the specific behaviour. Thus, self-efficacy exerts a powerful influence on the exercise behaviour of older populations’. The findings of Schutzer and Graves and this current review affirm the influence and importance of self-efficacy in older adult motivation to use exergames. Hence, it is vital to help older adults develop self-efficacy in exergame engagement.

Our study found older adults were motivated if health benefits could be achieved by playing exergames. Participants mentioned exergames would result in benefits of physical health, cognitive function and psychosocial well-being, as well as help them feel healthier, stronger and more energetic. Other empirical studies reported similar health benefits associated with exergame play [43,63]. Furthermore, some participants reported exergaming distracted away from feelings of pain. This is consistent with a previous study that found gaming time distracted participants from their daily-life problems and health-related impairments [53].

Sufficient support, instruction and feedback were other motivators to facilitate older adults to use exergames. Older adults use technologies with caution, and many do not know how to correctly perform the required movements, especially during the initial period. This finding corresponds with recent exergame studies among older adults that emphasized the importance of support and instruction to increase training motivation [53]. Therefore, providing sufficient support, instruction, and feedback is highly recommended when implementing exergames in older adults. In addition, studies are needed to explore how to effectively provide sufficient support, instruction and feedback to help older adults overcome relevant barriers.

Unpleasant experiences related to exergaming, such as fatigue and physical injury were found to decrease the motivation to participate. Safety measures should be taken to avoid excessive strain (e.g. warm-up before exergame playing and cool down after playing). Besides, exergame modifications that account for the specific needs of older adults may provide a more positive experience.

This study has several strengths. First, a robust methodological approach was adopted to identify and select articles relevant for inclusion. The process of meta-synthesis facilitated the synthesis of the findings from a range of qualitative studies to integrate the totality of the evidence regarding older adult experiences with exergaming programs. Second, the broad definition of exergaming used in the review [15] resulted in the inclusion and synthesis of a wide variety of qualitative data, further facilitating the generalizability of findings.

The search strategy used in this review is a potential limitation since we did not include methods for identifying grey literature or research published in languages other than English. Valuable information may have been overlooked because these sources were not incorporated. Second, this review only focused on older adult perceptions on exergaming programs; future research should explore other stakeholder perceptions on exergaming, such as family members, caregivers and service providers. The findings gleaned from such studies will inform the development of multi-faceted programs to target barriers to exergame engagement. Thus, future programs can be developed in collaboration with the different stakeholders to ensure optimal outputs. Furthermore, as this field is still relatively new and there were not many studies for each sample to provide sufficient information, we did not differentiate findings based on the different samples of the identified studies. Future studies that define more specific inclusion criteria would be more meaningful. In addition, the ConQual score of the synthesized findings was assessed as low, which may influence finding confidence [64]. Therefore, dependability and credibility should be considered in future studies, specifically, presenting researchers’ culturally or theoretically, acknowledging researchers’ influence on the research, and providing unequivocal findings. Finally, it must be acknowledged that the conclusions drawn from this review may have been influenced by the professional background of the authors.

Conclusion

This meta-synthesis provided synthesized qualitative evidence that can guide the design and implementation of exergame intervention programs for older adults. Three themes identified in the systematic review are as follows: older adult capability, opportunities in the exergaming program, and motivation in the exergaming programs. These themes might help identify factors for implementing effective exergaming programs. This study also provides a platform for future studies investigating how to incorporate COM-B theory into a structured exergaming program to promote physical activity in older adults by increasing capacity, opportunities, and motivation to exercise.

Implications for research

Recommendations for practice arising from the review were provided in Appendix 7, available in Age and Ageing online and, as per guidelines from the Joanna Briggs Institute, have been assigned a Grade of Recommendation [65]. Grade A is a strong recommendation, whereas Grade B is a weaker recommendation. Research recommendations are provided below. To successfully implement exergame intervention programs for older adults, it is essential to increase capability (consider age- or health-related impairments, improve exergame knowledge and skills, and cultivate positive attitudes toward exergaming), opportunities (adopt an older adult-friendly exergame design, and social influence), and motivation (enhance self-efficacy, provide adequate support, instruction and feedback, meet health needs and avoid unpleasant experiences related to exergaming).

Declaration of Conflict of Interest

None.

Declaration of Sources of Funding

This work was supported by the Central South University Innovation-driven project (Grant number CX20220335), the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant number 2020YFC2008500, 2020YFC2008503, 2020YFC2008602); the Special Funding for the Construction of Innovative Provinces in Hunan (Grant number 2020SK2055).

References

Yim J, Graham TC. Using games to increase exercise motivation.

Thach KS, Lederman RM, Waycott J. (2020). How older adults respond to the use of Virtual Reality for enrichment: a systematic review. Proceedings of the 32nd Australian Conferenceon Human-Computer Interaction. https://doi.org/10.1145/3441000.3441003

Aromataris E, Munn Z (Editors). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI, 2020. Available from https://synthesismanual.jbi.global; https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-01 https://doi.org/

Mol AM, Silva RS, Ishitani L. Design recommendations for the development of virtual reality focusing on the elderly, 2019.

Jeremic J, Zhang F, Kaufman D. (2019). Older Adults’ Perceptions About Commercially Available Xbox Kinect Exergames. In: Zhou J, Salvendy G. (eds) Human aspects of IT for the aged population. Design for the elderly and technology acceptance. HCII 2019. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Vol 11592. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-22012-9_14.

The Joanna Briggs Institute. The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual: 2015 edition/Supplement, The Joanna Briggs Institute, The University of Adelaide. https://nursing.lsuhsc.edu/JBI/docs/ReviewersManuals/Diagnostic-test-accuracy.pdf. (20 February 2022, date last accessed).

Michie S, Atkins L, West R. (2014) The Behaviour Change Wheel: A Guide to Designing Interventions. London: Silverback Publishing. www.behaviourchangewheel.com.

Nawaz A, Skjæret N, Ystmark K, Helbostad JL, Vereijken B, Svanæs D. Assessing seniors’ user experience (UX) of exergames for balance training. Proceedings of the 8th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction: Fun, Fast, Foundational. 2014; 10: 578–587.

Nawaz A, Waerstad M, Omholt K, et al. . Designingsimplified exergame for muscle and balance training in seniors: a concept of' out in nature'. Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Pervasive Computing Technologies for Healthcare. 2014; 05: 255269. https://doi.org/10.4108/icst.pervasivehealth.

Li J, Erdt M, Chen L, Cao Y, Lee S-Q, Theng Y-L. (2018). The social effects ofexergames on older adults: systematic review and metric analysis. J Med Internet Res 2018; 20: e10486. https://doi.org/10.2196/10486.

Rabideau ST. Effects of achievement motivation on behavior [EB/OL], 2005. http://www.personalityresearch.org/papers/rabideau.html (20 February 2022, date last accessed)

Stankevicius D, Jady HA, Drachen A, Schønau-Fog H. A factor-based exploration of player's continuation desire in free-to-play mobile games. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Interactive Digital Entertainment. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1609/aiide.v11i5.12848.

Comments