-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Mario Ulises Pérez-Zepeda, Judith Godin, Joshua J Armstrong, Melissa K Andrew, Arnold Mitnitski, Susan Kirkland, Kenneth Rockwood, Olga Theou, Frailty among middle-aged and older Canadians: population norms for the frailty index using the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging, Age and Ageing, Volume 50, Issue 2, March 2021, Pages 447–456, https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afaa144

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

frailty is a public health priority now that the global population is ageing at a rapid rate. A scientifically sound tool to measure frailty and generate population-based reference values is a starting point.

in this report, our objectives were to operationalize frailty as deficit accumulation using a standard frailty index (FI), describe levels of frailty in Canadians ≥45 years old and provide national normative data.

this is a secondary analysis of the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA) baseline data.

about 51,338 individuals (weighted to represent 13,232,651 Canadians), aged 45–85 years, from the tracking and comprehensive cohorts of CLSA.

after screening all available variables in the pooled dataset, 52 items were selected to construct an FI. Descriptive statistics for the FI and normative data derived from quantile regressions were developed.

the average age of the participants was 60.3 years (95% confidence interval [CI]: 60.2–60.5), and 51.5% were female (95% CI: 50.8–52.2). The mean FI score was 0.07 (95% CI: 0.07–0.08) with a standard deviation of 0.06. Frailty was higher among females and with increasing age, and scores >0.2 were present in 4.2% of the sample. National normative data were identified for each year of age for males and females.

the standardized frailty tool and the population-based normative frailty values can help inform discussions about frailty, setting a new bar in the field. Such information can be used by clinicians, researchers, stakeholders and the general public to understand frailty, especially its relationship with age and sex.

Key points

Frailty was higher among female Canadians and with increasing age.

Frailty index scores >0.2 were present in 4.2% of the CLSA sample.

We identified national normative frailty values for Canadians 45–85 years old.

Introduction

In 2016, the number of older adults (aged 65 and over) in the Canadian population surpassed the number of those aged 14 and under [1]. Moreover, it is expected that by year 2030, the proportion of older Canadians will grow from 17.2% (2018) up to 29.5%. This shift in age distribution will have profound implications for population health and, as a consequence, for health-care planning. Frailty is a complex challenge associated with population ageing that threatens those health care systems which focus on overspecialisation. The complexity of frailty—and multiplicity of needs—can be quantified in a way that embraces the multifactorial nature of ageing [2], since it is understood that the problems of ageing come as a package [3].

Frailty is a condition usually related to adverse outcomes [4] and is considered to be a public health challenge [5] due to the increasing number of frail older adults. Moreover, it is a common condition; approximately 10.9% of individuals ≥65 years are frail [6]. Frailty develops as a result of age-related decline across physiological systems, which collectively translates into increased vulnerability [7]. Consequently, frailty impacts the quality of life of older adults and their ability to function independently, which leads to costly hospitalization, institutionalization and mortality [2,8–9]. Although many commentators rightly decry warnings of a ‘silver tsunami’ or ‘demographic time bomb’, there is no doubt that the contemporary Canadian health care system is finding it difficult to cope with the complex needs of older people whose health challenges are defined by multiple, interacting medical and social problems [10].

Measuring frailty is a key to understanding its nature, including opportunities for amelioration, and attenuation of its progression. Of the many instruments available to measure frailty [2], most commentators recognize two types: frailty as a specific physical syndrome (frailty phenotype) [11] and frailty as deficit accumulation (frailty index [FI]) [8,9]. The FI is widely used in research and clinical settings, including in routine primary care in England [12], and has consistently shown to predict mortality and other adverse outcomes, even among people of the same age [2]. The FI was designed to be a state variable that integrates multiple sources of health information to reflect the extent of vulnerability, illness and thereby proximity to a range of adverse health outcomes [13,14]. Using the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA), we can extend the understanding of frailty by examining frailty in middle-aged and older adults. The objectives of this study were: (i) to provide a standardized FI using the CLSA data; (ii) to describe frailty levels of Canadians over the age of 45 years and (iii) to provide national normative data for frailty.

Methods

The Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging

We conducted secondary analysis of the cross-sectional CLSA baseline data collected between 2011 and 2015. The overall aim of the CLSA is to find ways to improve the health of Canadians by increasing our understanding of the ageing process and the factors that influence it. The sample of 51,338 community-dwelling Canadians between the ages of 45–85 will be followed for 20 years, gathering biological, medical, psychological, social, lifestyle and economic data at 3-year intervals. Exclusion criteria for the baseline assessment were: residents of the three Canadian territories; persons living on federal First Nations reserves; full-time members of the Canadian Armed Forces; people unable to respond in English or French; the presence of cognitive impairment at the time of recruitment and institutionalized individuals (e.g. living in long-term care facilities).

The CLSA has two arms: tracking and comprehensive. The tracking cohort consists of 21,241 Canadians randomly selected from across the 10 provinces. Data for this cohort were collected through a 60-minutes telephone interview. The comprehensive cohort consists of 30,097 participants who were randomly selected from within 25–50 km of 11 data collection sites (DCS) across seven Canadian provinces (Prince Edward Island, Saskatchewan and New Brunswick were not included). Data were collected at a home visit, while clinical, biological and physical assessments (including the collection and processing of blood and urine samples) were collected at the DCS. Researchers can learn more about the CLSA and submit a data access request through clsa-elcv.ca. The CLSA protocol is available at https://clsa-elcv.ca/doc/511 and more details on the objectives, procedures and sampling are available elsewhere [15–18]. Here, we used the pooled dataset, which combines the two study arms.

Frailty

We constructed an FI based on standard procedures [19].

Selection of health-related items

We first selected variables that were available in both CLSA arms and could identify deficits in health, typically defined as symptoms, signs, diseases, disability and mental health problems [20].

Coding

Selected items were transformed into a 0 (no deficit) to 1 (deficit) scale. Interval or ordinal variables with more than two responses were coded as a fraction of the complete deficit. For instance, the self-rated health question’s five response options were coded: Excellent—0, Very good—0.25, Good—0.5, Fair—0.75 and Poor—1.

Screening of coded items

Coded variables were screened in terms of the prevalence of deficits, correlation with age and missing values. Typically, items with very low prevalence of a deficit (<1%), which cannot be combined with other items, are excluded from the FI as uninformative. Here, as the CLSA includes middle-aged adults (i.e. ≤65 years) who will have at least 20 years of follow-up, we expect that the prevalence of many such deficits will become informative during follow-up and therefore are counted in the FI. Similarly, items with >5% missing values are typically excluded from the FI, but in order to include information on cognition, we increased this criterion to 12% (since cognitive tests had high missing values); sensitivity analyses were done to examine the impact of these changes in the performance of the FI (Appendix 3). Correlation with age was assessed by plotting the mean of the item against age as well as testing the Spearman correlation coefficients.

FI calculation

Possible FI scores range from zero to one with those individuals scoring zero having the lowest level of frailty. For instance, if an individual had 15 deficits of 52 considered, the FI score would be 15/52 = 0.29. We did not calculate FI scores for participants with missing values for ≥20% of the deficits.

Statistical analysis

We used the trimmed inflation weights, following CLSA procedures, to report population-representative estimates [21]. The FI was described using the mean and corresponding 95% CIs. Histograms graphically depict the distribution of the FI for the whole sample, for males and females, and by 5-year interval age groups. To assess the relationship of the FI with age for the whole sample and for males and females, the FI was transformed into its natural logarithm (log-FI, leaving zeros) and regressed as the dependent variable, with age as the independent variable. Predicted values of these regressions were further transformed into its exponentials, and the mean of these transformed values was plotted for each year of age. Frequencies of 0.1 intervals groups (≤0.1, 0.11–0.2, 0.21–0.3 and ≥0.31) were explored for age and sex groups.

Norms were derived from quantile regressions of the log-FI values (5th percentile intervals, in addition to the 1st and 99th percentiles). Quantile regression models fit the quantiles of the conditional distribution as linear functions of the independent variables. Predictive values from the log-FI quantile regressions were transformed into their exponentials and tabulated for each year of age and sex. Furthermore, these predictive values were plotted in colors against each year of age: ranging from green (less frail) to red (frailer), for males and females separately. In addition, the median for the 45-year-old individuals was included in the plots as a reference. We conducted all analyses using STATA 16.0 (StataCorp LLC).

Our protocol was approved by the CLSA Data and Sample Access Committee (ID #160610). As a matter of policy, our local Research Ethics Committee (Nova Scotia Health Authority Research Ethics Board) does not review research involving secondary analyses of datasets that contain deidentified individual-level data.

Results

FI construction

After screening 75 health-related items available in the pooled dataset, 52 items were included in the FI (Table 1 and Supplementary Figure 1, Appendix 1). See Appendix 2 for the detailed findings of the screening. A complete protocol of the FI along with Supplementary Material (scored questionnaires, syntax, etc.) will be available upon request or in the following webpage: www.geriatricmedicineresearch.ca. Only 87 (0.1%) individuals were missing ≥10 items (≥20% of the 52 items included) and were excluded from analysis.

| Domain . | Item . | Question/description . |

|---|---|---|

| Self-rated health, vision, hearing | Health | In general, would you say your health is excellent, very good, good, fair or poor? |

| Vision | Is your eyesight, using glasses or corrective lens if you use them: excellent, very good, good, fair or poor? | |

| Hearing | Is your hearing, using a hearing aid if you use one: excellent, very good, good, fair or poor? | |

| Chronic conditions | Osteoarthritis | Has a doctor ever told you that you have osteoarthritis in the knee, hip or hands? |

| Arthritis | Has a doctor ever told you that you have rheumatoid arthritis or any other type of arthritis? | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Has a doctor told you that you have/had any of the following: emphysema, chronic bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or chronic changes in lungs due to smoking? | |

| High-blood pressure | Has a doctor ever told you that you have high-blood pressure or hypertension? | |

| Diabetes mellitus | Has a doctor ever told you that you have diabetes, borderline diabetes or that your blood sugar is high? | |

| Chronic heart failure | Has a doctor ever told you that you have heart disease (including congestive heart failure, or CHF)? | |

| Angina | Has a doctor ever told you that you have angina (or chest pain due to heart disease)? | |

| Acute myocardial infarction | Has a doctor ever told you that you have had a heart attack or myocardial infarction? | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | Has a doctor ever told you that you have peripheral vascular disease or poor circulation in your limbs? | |

| Stroke | Has a doctor ever told you that you have experienced a stroke or CVA (cerebrovascular accident)? | |

| Transient ischemic attack | Has a doctor ever told you that you have experienced a mini-stroke or TIA? (Transient Ischemic Attack)? | |

| Memory problem | Has a doctor ever told you that you have a memory problem? | |

| Alzheimer’s disease | Has a doctor ever told you that you have Alzheimer’s disease? | |

| Parkinson’s disease | Has a doctor ever told you that you have Parkinson’s disease? | |

| Peptic ulcer diseae | Has a doctor ever told you that you have intestinal or stomach ulcers? | |

| Colitis | Has a doctor ever told you that you have a bowel disorder such as Crohn’s Disease, ulcerative colitis, or Irritable Bowel Syndrome? | |

| Bowel incontinence | Has a doctor ever told you that you experience bowel incontinence? | |

| Urinary incontinence | How often do you wet or soil yourself (either day or night)? | |

| Cataract | Has a doctor ever told you that you have cataracts? | |

| Glaucoma | Has a doctor ever told you that you have glaucoma? | |

| Macular degeneration | Has a doctor ever told you that you have macular degeneration? | |

| Cancer | Has a doctor ever told you that you have cancer? | |

| Osteoporosis | Has a doctor ever told you that you have osteoporosis, sometimes called low bone mineral density, or thin, brittle, or weak bones? | |

| Back pain | Has a doctor ever told you that you have back problems, excluding fibromyalgia and arthritis? | |

| Hypothyroidism | Has a doctor ever told you that you have an UNDER-active thyroid gland (sometimes calles hypothyroidism or myxedema)? | |

| Hyperthyroidism | Has a doctor ever told you that you have an OVER-active thyroid gland (sometimes called hyperthyroidism or Graves’ disease)? | |

| Kidney failure | Has a doctor ever told you that you have kidney disease or kidney failure? | |

| Pneumonia | In the past year, have you seen a doctor for pneumonia? | |

| Urinary tract infection | In the past year, have you seen a doctor for urinary tract infection? | |

| Falls | How many times have you fallen in the past 12 months? | |

| Activities of daily living | Dressing | Can you dress and undress yourself without help (including picking out clothes and putting on socks & shoes)? |

| Grooming | Can you take care of your own appearance without help, for example, combing your hair, shaving (if male)? | |

| Walking | Can you walk without help? | |

| Getting in/out of bed | Can you get in and out of bed without any help or aids? | |

| Bathing | Can you take a bath or shower without help? | |

| Instrumental activities of daily living | Using the phone | Can you use the telephone without help, including looking up numbers and dialing? |

| Using transport | Can you get to places out of walking distance without help (i.e. you drive your own car, or travel alone on buses, or taxis)? | |

| Shopping | Can you go shopping for groceries or clothes without help (taking care of all shopping needs yourself)? | |

| Cooking | Can you prepare your own meals without help (i.e. you plan and cook full meals yourself? | |

| Doing housework | Can you do your housework without help (i.e. you can clean floors, etc.)? | |

| Taking medicine | Can you take your own medicine without help (in the right doses at the right time)? | |

| Managing money | Can you handle your own money without help (i.e. you write cheques, pay bills, etc.)? | |

| Cognitive function | Mental alternation test | Count and tell the alphabet backwards alternating numbers and letters |

| Verbal fluency | As many names of animals, the participant recalls in 1 minute | |

| Immediate recall | Number of words recalled immediately from a list | |

| Delayed recall | Number of words recalled from a list minutes later | |

| Mental health | Effort | How often did you feel that everything you did was an effort |

| Felt lonely | How often did you feel lonely? | |

| Could not get going | How often did you feel that you could not ‘get going’? |

| Domain . | Item . | Question/description . |

|---|---|---|

| Self-rated health, vision, hearing | Health | In general, would you say your health is excellent, very good, good, fair or poor? |

| Vision | Is your eyesight, using glasses or corrective lens if you use them: excellent, very good, good, fair or poor? | |

| Hearing | Is your hearing, using a hearing aid if you use one: excellent, very good, good, fair or poor? | |

| Chronic conditions | Osteoarthritis | Has a doctor ever told you that you have osteoarthritis in the knee, hip or hands? |

| Arthritis | Has a doctor ever told you that you have rheumatoid arthritis or any other type of arthritis? | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Has a doctor told you that you have/had any of the following: emphysema, chronic bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or chronic changes in lungs due to smoking? | |

| High-blood pressure | Has a doctor ever told you that you have high-blood pressure or hypertension? | |

| Diabetes mellitus | Has a doctor ever told you that you have diabetes, borderline diabetes or that your blood sugar is high? | |

| Chronic heart failure | Has a doctor ever told you that you have heart disease (including congestive heart failure, or CHF)? | |

| Angina | Has a doctor ever told you that you have angina (or chest pain due to heart disease)? | |

| Acute myocardial infarction | Has a doctor ever told you that you have had a heart attack or myocardial infarction? | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | Has a doctor ever told you that you have peripheral vascular disease or poor circulation in your limbs? | |

| Stroke | Has a doctor ever told you that you have experienced a stroke or CVA (cerebrovascular accident)? | |

| Transient ischemic attack | Has a doctor ever told you that you have experienced a mini-stroke or TIA? (Transient Ischemic Attack)? | |

| Memory problem | Has a doctor ever told you that you have a memory problem? | |

| Alzheimer’s disease | Has a doctor ever told you that you have Alzheimer’s disease? | |

| Parkinson’s disease | Has a doctor ever told you that you have Parkinson’s disease? | |

| Peptic ulcer diseae | Has a doctor ever told you that you have intestinal or stomach ulcers? | |

| Colitis | Has a doctor ever told you that you have a bowel disorder such as Crohn’s Disease, ulcerative colitis, or Irritable Bowel Syndrome? | |

| Bowel incontinence | Has a doctor ever told you that you experience bowel incontinence? | |

| Urinary incontinence | How often do you wet or soil yourself (either day or night)? | |

| Cataract | Has a doctor ever told you that you have cataracts? | |

| Glaucoma | Has a doctor ever told you that you have glaucoma? | |

| Macular degeneration | Has a doctor ever told you that you have macular degeneration? | |

| Cancer | Has a doctor ever told you that you have cancer? | |

| Osteoporosis | Has a doctor ever told you that you have osteoporosis, sometimes called low bone mineral density, or thin, brittle, or weak bones? | |

| Back pain | Has a doctor ever told you that you have back problems, excluding fibromyalgia and arthritis? | |

| Hypothyroidism | Has a doctor ever told you that you have an UNDER-active thyroid gland (sometimes calles hypothyroidism or myxedema)? | |

| Hyperthyroidism | Has a doctor ever told you that you have an OVER-active thyroid gland (sometimes called hyperthyroidism or Graves’ disease)? | |

| Kidney failure | Has a doctor ever told you that you have kidney disease or kidney failure? | |

| Pneumonia | In the past year, have you seen a doctor for pneumonia? | |

| Urinary tract infection | In the past year, have you seen a doctor for urinary tract infection? | |

| Falls | How many times have you fallen in the past 12 months? | |

| Activities of daily living | Dressing | Can you dress and undress yourself without help (including picking out clothes and putting on socks & shoes)? |

| Grooming | Can you take care of your own appearance without help, for example, combing your hair, shaving (if male)? | |

| Walking | Can you walk without help? | |

| Getting in/out of bed | Can you get in and out of bed without any help or aids? | |

| Bathing | Can you take a bath or shower without help? | |

| Instrumental activities of daily living | Using the phone | Can you use the telephone without help, including looking up numbers and dialing? |

| Using transport | Can you get to places out of walking distance without help (i.e. you drive your own car, or travel alone on buses, or taxis)? | |

| Shopping | Can you go shopping for groceries or clothes without help (taking care of all shopping needs yourself)? | |

| Cooking | Can you prepare your own meals without help (i.e. you plan and cook full meals yourself? | |

| Doing housework | Can you do your housework without help (i.e. you can clean floors, etc.)? | |

| Taking medicine | Can you take your own medicine without help (in the right doses at the right time)? | |

| Managing money | Can you handle your own money without help (i.e. you write cheques, pay bills, etc.)? | |

| Cognitive function | Mental alternation test | Count and tell the alphabet backwards alternating numbers and letters |

| Verbal fluency | As many names of animals, the participant recalls in 1 minute | |

| Immediate recall | Number of words recalled immediately from a list | |

| Delayed recall | Number of words recalled from a list minutes later | |

| Mental health | Effort | How often did you feel that everything you did was an effort |

| Felt lonely | How often did you feel lonely? | |

| Could not get going | How often did you feel that you could not ‘get going’? |

| Domain . | Item . | Question/description . |

|---|---|---|

| Self-rated health, vision, hearing | Health | In general, would you say your health is excellent, very good, good, fair or poor? |

| Vision | Is your eyesight, using glasses or corrective lens if you use them: excellent, very good, good, fair or poor? | |

| Hearing | Is your hearing, using a hearing aid if you use one: excellent, very good, good, fair or poor? | |

| Chronic conditions | Osteoarthritis | Has a doctor ever told you that you have osteoarthritis in the knee, hip or hands? |

| Arthritis | Has a doctor ever told you that you have rheumatoid arthritis or any other type of arthritis? | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Has a doctor told you that you have/had any of the following: emphysema, chronic bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or chronic changes in lungs due to smoking? | |

| High-blood pressure | Has a doctor ever told you that you have high-blood pressure or hypertension? | |

| Diabetes mellitus | Has a doctor ever told you that you have diabetes, borderline diabetes or that your blood sugar is high? | |

| Chronic heart failure | Has a doctor ever told you that you have heart disease (including congestive heart failure, or CHF)? | |

| Angina | Has a doctor ever told you that you have angina (or chest pain due to heart disease)? | |

| Acute myocardial infarction | Has a doctor ever told you that you have had a heart attack or myocardial infarction? | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | Has a doctor ever told you that you have peripheral vascular disease or poor circulation in your limbs? | |

| Stroke | Has a doctor ever told you that you have experienced a stroke or CVA (cerebrovascular accident)? | |

| Transient ischemic attack | Has a doctor ever told you that you have experienced a mini-stroke or TIA? (Transient Ischemic Attack)? | |

| Memory problem | Has a doctor ever told you that you have a memory problem? | |

| Alzheimer’s disease | Has a doctor ever told you that you have Alzheimer’s disease? | |

| Parkinson’s disease | Has a doctor ever told you that you have Parkinson’s disease? | |

| Peptic ulcer diseae | Has a doctor ever told you that you have intestinal or stomach ulcers? | |

| Colitis | Has a doctor ever told you that you have a bowel disorder such as Crohn’s Disease, ulcerative colitis, or Irritable Bowel Syndrome? | |

| Bowel incontinence | Has a doctor ever told you that you experience bowel incontinence? | |

| Urinary incontinence | How often do you wet or soil yourself (either day or night)? | |

| Cataract | Has a doctor ever told you that you have cataracts? | |

| Glaucoma | Has a doctor ever told you that you have glaucoma? | |

| Macular degeneration | Has a doctor ever told you that you have macular degeneration? | |

| Cancer | Has a doctor ever told you that you have cancer? | |

| Osteoporosis | Has a doctor ever told you that you have osteoporosis, sometimes called low bone mineral density, or thin, brittle, or weak bones? | |

| Back pain | Has a doctor ever told you that you have back problems, excluding fibromyalgia and arthritis? | |

| Hypothyroidism | Has a doctor ever told you that you have an UNDER-active thyroid gland (sometimes calles hypothyroidism or myxedema)? | |

| Hyperthyroidism | Has a doctor ever told you that you have an OVER-active thyroid gland (sometimes called hyperthyroidism or Graves’ disease)? | |

| Kidney failure | Has a doctor ever told you that you have kidney disease or kidney failure? | |

| Pneumonia | In the past year, have you seen a doctor for pneumonia? | |

| Urinary tract infection | In the past year, have you seen a doctor for urinary tract infection? | |

| Falls | How many times have you fallen in the past 12 months? | |

| Activities of daily living | Dressing | Can you dress and undress yourself without help (including picking out clothes and putting on socks & shoes)? |

| Grooming | Can you take care of your own appearance without help, for example, combing your hair, shaving (if male)? | |

| Walking | Can you walk without help? | |

| Getting in/out of bed | Can you get in and out of bed without any help or aids? | |

| Bathing | Can you take a bath or shower without help? | |

| Instrumental activities of daily living | Using the phone | Can you use the telephone without help, including looking up numbers and dialing? |

| Using transport | Can you get to places out of walking distance without help (i.e. you drive your own car, or travel alone on buses, or taxis)? | |

| Shopping | Can you go shopping for groceries or clothes without help (taking care of all shopping needs yourself)? | |

| Cooking | Can you prepare your own meals without help (i.e. you plan and cook full meals yourself? | |

| Doing housework | Can you do your housework without help (i.e. you can clean floors, etc.)? | |

| Taking medicine | Can you take your own medicine without help (in the right doses at the right time)? | |

| Managing money | Can you handle your own money without help (i.e. you write cheques, pay bills, etc.)? | |

| Cognitive function | Mental alternation test | Count and tell the alphabet backwards alternating numbers and letters |

| Verbal fluency | As many names of animals, the participant recalls in 1 minute | |

| Immediate recall | Number of words recalled immediately from a list | |

| Delayed recall | Number of words recalled from a list minutes later | |

| Mental health | Effort | How often did you feel that everything you did was an effort |

| Felt lonely | How often did you feel lonely? | |

| Could not get going | How often did you feel that you could not ‘get going’? |

| Domain . | Item . | Question/description . |

|---|---|---|

| Self-rated health, vision, hearing | Health | In general, would you say your health is excellent, very good, good, fair or poor? |

| Vision | Is your eyesight, using glasses or corrective lens if you use them: excellent, very good, good, fair or poor? | |

| Hearing | Is your hearing, using a hearing aid if you use one: excellent, very good, good, fair or poor? | |

| Chronic conditions | Osteoarthritis | Has a doctor ever told you that you have osteoarthritis in the knee, hip or hands? |

| Arthritis | Has a doctor ever told you that you have rheumatoid arthritis or any other type of arthritis? | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Has a doctor told you that you have/had any of the following: emphysema, chronic bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or chronic changes in lungs due to smoking? | |

| High-blood pressure | Has a doctor ever told you that you have high-blood pressure or hypertension? | |

| Diabetes mellitus | Has a doctor ever told you that you have diabetes, borderline diabetes or that your blood sugar is high? | |

| Chronic heart failure | Has a doctor ever told you that you have heart disease (including congestive heart failure, or CHF)? | |

| Angina | Has a doctor ever told you that you have angina (or chest pain due to heart disease)? | |

| Acute myocardial infarction | Has a doctor ever told you that you have had a heart attack or myocardial infarction? | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | Has a doctor ever told you that you have peripheral vascular disease or poor circulation in your limbs? | |

| Stroke | Has a doctor ever told you that you have experienced a stroke or CVA (cerebrovascular accident)? | |

| Transient ischemic attack | Has a doctor ever told you that you have experienced a mini-stroke or TIA? (Transient Ischemic Attack)? | |

| Memory problem | Has a doctor ever told you that you have a memory problem? | |

| Alzheimer’s disease | Has a doctor ever told you that you have Alzheimer’s disease? | |

| Parkinson’s disease | Has a doctor ever told you that you have Parkinson’s disease? | |

| Peptic ulcer diseae | Has a doctor ever told you that you have intestinal or stomach ulcers? | |

| Colitis | Has a doctor ever told you that you have a bowel disorder such as Crohn’s Disease, ulcerative colitis, or Irritable Bowel Syndrome? | |

| Bowel incontinence | Has a doctor ever told you that you experience bowel incontinence? | |

| Urinary incontinence | How often do you wet or soil yourself (either day or night)? | |

| Cataract | Has a doctor ever told you that you have cataracts? | |

| Glaucoma | Has a doctor ever told you that you have glaucoma? | |

| Macular degeneration | Has a doctor ever told you that you have macular degeneration? | |

| Cancer | Has a doctor ever told you that you have cancer? | |

| Osteoporosis | Has a doctor ever told you that you have osteoporosis, sometimes called low bone mineral density, or thin, brittle, or weak bones? | |

| Back pain | Has a doctor ever told you that you have back problems, excluding fibromyalgia and arthritis? | |

| Hypothyroidism | Has a doctor ever told you that you have an UNDER-active thyroid gland (sometimes calles hypothyroidism or myxedema)? | |

| Hyperthyroidism | Has a doctor ever told you that you have an OVER-active thyroid gland (sometimes called hyperthyroidism or Graves’ disease)? | |

| Kidney failure | Has a doctor ever told you that you have kidney disease or kidney failure? | |

| Pneumonia | In the past year, have you seen a doctor for pneumonia? | |

| Urinary tract infection | In the past year, have you seen a doctor for urinary tract infection? | |

| Falls | How many times have you fallen in the past 12 months? | |

| Activities of daily living | Dressing | Can you dress and undress yourself without help (including picking out clothes and putting on socks & shoes)? |

| Grooming | Can you take care of your own appearance without help, for example, combing your hair, shaving (if male)? | |

| Walking | Can you walk without help? | |

| Getting in/out of bed | Can you get in and out of bed without any help or aids? | |

| Bathing | Can you take a bath or shower without help? | |

| Instrumental activities of daily living | Using the phone | Can you use the telephone without help, including looking up numbers and dialing? |

| Using transport | Can you get to places out of walking distance without help (i.e. you drive your own car, or travel alone on buses, or taxis)? | |

| Shopping | Can you go shopping for groceries or clothes without help (taking care of all shopping needs yourself)? | |

| Cooking | Can you prepare your own meals without help (i.e. you plan and cook full meals yourself? | |

| Doing housework | Can you do your housework without help (i.e. you can clean floors, etc.)? | |

| Taking medicine | Can you take your own medicine without help (in the right doses at the right time)? | |

| Managing money | Can you handle your own money without help (i.e. you write cheques, pay bills, etc.)? | |

| Cognitive function | Mental alternation test | Count and tell the alphabet backwards alternating numbers and letters |

| Verbal fluency | As many names of animals, the participant recalls in 1 minute | |

| Immediate recall | Number of words recalled immediately from a list | |

| Delayed recall | Number of words recalled from a list minutes later | |

| Mental health | Effort | How often did you feel that everything you did was an effort |

| Felt lonely | How often did you feel lonely? | |

| Could not get going | How often did you feel that you could not ‘get going’? |

Descriptive statistics

Of 51,338 individuals weighted to represent 13,232,651 Canadians aged 45–85 years, 51.5% were female (95% CI: 50.8–52.2). The average age was 60.3 years (95% CI: 60.2–60.5). The mean FI score was 0.07 (95% CI: 0.07–0.08; standard deviation = 0.06). The FI was higher for females and for those in the oldest age groups (Table 2). The minimum FI score was zero (n = 341 [0.6%] scoring 0) and the maximum was 0.47. The median was 0.06 and the 99th percentile was 0.26.

| Variable . | Weighted frequency . | Weighted mean FI (95% CI) . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | Absolute N . | Relative, % (95% CI) . | . |

| Overall | 13,232,651 | 100 | 0.08 (0.07–0.08) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 6,417,836 | 48.5 (47.8–49.2) | 0.07 (0.07–0.08) |

| Female | 6,814,815 | 51.5 (50.8–52.2) | 0.08 (0.08–0.09) |

| Age group, year | |||

| 45–49 | 1,857,626 | 14.1 (13.6–14.4) | 0.05 (0.05–0.06) |

| 50–54 | 3,113,019 | 23.5 (22.8–24.1) | 0.06 (0.05–0.06) |

| 55–59 | 1,922,850 | 14.5 (14–15) | 0.07 (0.07–0.08) |

| 60–64 | 2,163,171 | 16.4 (15.8–16.8) | 0.08 (0.07–0.08) |

| 65–69 | 1,500,274 | 11.3 (10.9–11.7) | 0.09 (0.09–0.1) |

| 70–74 | 1,036,039 | 7.8 (7.5–8.2) | 0.1 (0.1–0.11) |

| 75–79 | 987,351 | 7.5 (7.1–7.7) | 0.12 (0.12–0.13) |

| 80–85 | 652,313 | 4.9 (4.6–5.1) | 0.13 (0.13–0.14) |

| Variable . | Weighted frequency . | Weighted mean FI (95% CI) . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | Absolute N . | Relative, % (95% CI) . | . |

| Overall | 13,232,651 | 100 | 0.08 (0.07–0.08) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 6,417,836 | 48.5 (47.8–49.2) | 0.07 (0.07–0.08) |

| Female | 6,814,815 | 51.5 (50.8–52.2) | 0.08 (0.08–0.09) |

| Age group, year | |||

| 45–49 | 1,857,626 | 14.1 (13.6–14.4) | 0.05 (0.05–0.06) |

| 50–54 | 3,113,019 | 23.5 (22.8–24.1) | 0.06 (0.05–0.06) |

| 55–59 | 1,922,850 | 14.5 (14–15) | 0.07 (0.07–0.08) |

| 60–64 | 2,163,171 | 16.4 (15.8–16.8) | 0.08 (0.07–0.08) |

| 65–69 | 1,500,274 | 11.3 (10.9–11.7) | 0.09 (0.09–0.1) |

| 70–74 | 1,036,039 | 7.8 (7.5–8.2) | 0.1 (0.1–0.11) |

| 75–79 | 987,351 | 7.5 (7.1–7.7) | 0.12 (0.12–0.13) |

| 80–85 | 652,313 | 4.9 (4.6–5.1) | 0.13 (0.13–0.14) |

aA total of 51,338 Canadians were included in the CLSA baseline assessment.

| Variable . | Weighted frequency . | Weighted mean FI (95% CI) . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | Absolute N . | Relative, % (95% CI) . | . |

| Overall | 13,232,651 | 100 | 0.08 (0.07–0.08) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 6,417,836 | 48.5 (47.8–49.2) | 0.07 (0.07–0.08) |

| Female | 6,814,815 | 51.5 (50.8–52.2) | 0.08 (0.08–0.09) |

| Age group, year | |||

| 45–49 | 1,857,626 | 14.1 (13.6–14.4) | 0.05 (0.05–0.06) |

| 50–54 | 3,113,019 | 23.5 (22.8–24.1) | 0.06 (0.05–0.06) |

| 55–59 | 1,922,850 | 14.5 (14–15) | 0.07 (0.07–0.08) |

| 60–64 | 2,163,171 | 16.4 (15.8–16.8) | 0.08 (0.07–0.08) |

| 65–69 | 1,500,274 | 11.3 (10.9–11.7) | 0.09 (0.09–0.1) |

| 70–74 | 1,036,039 | 7.8 (7.5–8.2) | 0.1 (0.1–0.11) |

| 75–79 | 987,351 | 7.5 (7.1–7.7) | 0.12 (0.12–0.13) |

| 80–85 | 652,313 | 4.9 (4.6–5.1) | 0.13 (0.13–0.14) |

| Variable . | Weighted frequency . | Weighted mean FI (95% CI) . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | Absolute N . | Relative, % (95% CI) . | . |

| Overall | 13,232,651 | 100 | 0.08 (0.07–0.08) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 6,417,836 | 48.5 (47.8–49.2) | 0.07 (0.07–0.08) |

| Female | 6,814,815 | 51.5 (50.8–52.2) | 0.08 (0.08–0.09) |

| Age group, year | |||

| 45–49 | 1,857,626 | 14.1 (13.6–14.4) | 0.05 (0.05–0.06) |

| 50–54 | 3,113,019 | 23.5 (22.8–24.1) | 0.06 (0.05–0.06) |

| 55–59 | 1,922,850 | 14.5 (14–15) | 0.07 (0.07–0.08) |

| 60–64 | 2,163,171 | 16.4 (15.8–16.8) | 0.08 (0.07–0.08) |

| 65–69 | 1,500,274 | 11.3 (10.9–11.7) | 0.09 (0.09–0.1) |

| 70–74 | 1,036,039 | 7.8 (7.5–8.2) | 0.1 (0.1–0.11) |

| 75–79 | 987,351 | 7.5 (7.1–7.7) | 0.12 (0.12–0.13) |

| 80–85 | 652,313 | 4.9 (4.6–5.1) | 0.13 (0.13–0.14) |

aA total of 51,338 Canadians were included in the CLSA baseline assessment.

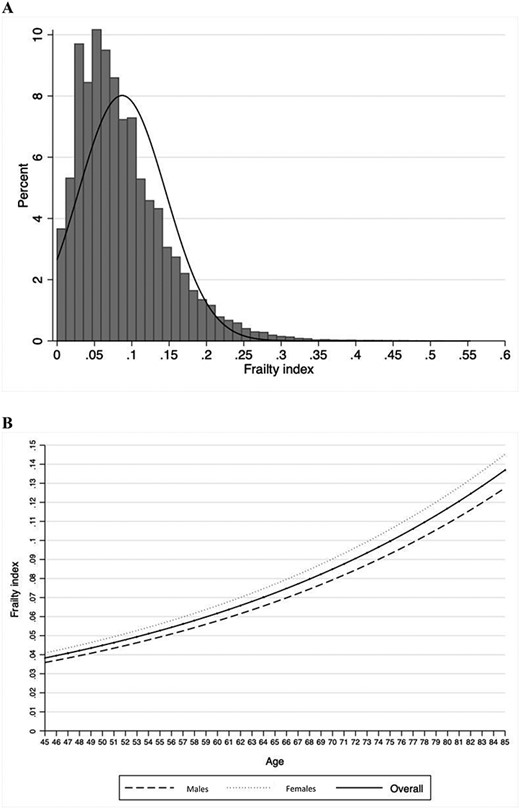

The FI distribution was skewed to the right (Figure 1a). The distribution broadens with age, becoming less skewed (Supplementary Figures 2 and 3, Appendix 1). The FI increased exponentially with age; the log-FI slope increased at an annual rate of 0.03 (95% CI: 0.03–0.03). Across all ages, females had higher FI scores than males (Figure 1b).

Distribution of the FI (a) and association of the FI with age (b).

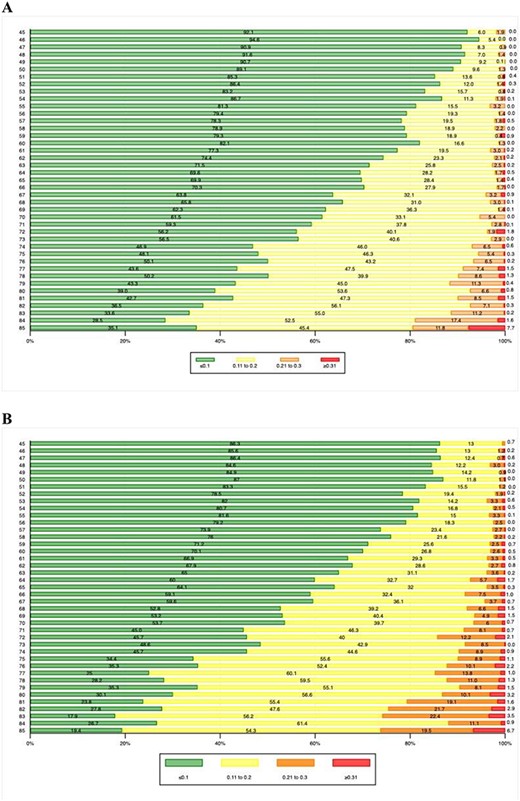

The proportion of males with FI ≤0.1, 0.11–0.2, 0.21–0.3 and ≥0.31 was 75.5, 21.5, 2.4 and 0.6%, respectively. The proportion of females with FI ≤0.1, 0.11–0.2, 0.21–0.3 and ≥0.31 was 67.7, 27.2, 4.4 and 0.7%, respectively. Detailed prevalence estimates of these frailty levels by sex and age groups can be found in Figure 2.

Proportion of FI groups, at each year of age for males (a) and females (b).

FI norms

Figure 3 shows the normative FI scores for males and females, according to the fitted 5th percentile intervals (except for the 1st and 99th percentiles) for each year of age. See Supplemental Tables 1 and 2 in Appendix 1 for specific normative data values.

FI norms by age for males (a) and females (b). Note: Increasing percentiles are represented with heat map colors. The black line represents the median FI score for 45 year olds.

Discussion

This study reports a standardized FI and provides normative values for Canadian males and females 45–85 years old using the largest and most recent national ageing study, the CLSA. These data brought to attention that frailty is not just a subject that affects older people; it can be measured from middle age, thus expanding the possibilities of prevention and enhancing the life-course focus on frailty development.

This sets a new bar for frailty discourse, since normative data will be useful for researchers interested in frailty or comparing frailty levels of their sample to the CLSA data. Also, this standardized FI may be useful for clinicians to inform their daily practice, for stakeholders to examine how the population is ageing and for individuals who would like to self-assess their frailty levels and interpret their scores against those of people of their similar age and sex.

The characteristics of this FI were similar to previous studies: there was a non-linear increase of FI scores with age (3.2% increase per year) [13,14]; FI scores were higher for females and the limit was lower when compared with other populations, even in the oldest individuals—a well-described characteristic of higher income countries [2].

Frailty is a complex concept to operationalize, a fact that has created confusion among researchers and clinicians regarding which tools to use. Having norms aids with comparisons of frailty levels not only between individuals but also between populations and can advance the field of ageing research and geriatric care. It gives a solid platform to establish interventions and has the potential to be used in health-care decision-making (i.e. budget allocation) [22,23]. Other FIs could use this new tool as a reference standard for comparison purposes [24].

We did not use socio-demographic factors such as race and marital status to adjust the normative frailty data. This was previously done when normative frailty data were proposed for Dutch people using the Tilburg Frailty Indicator [25]. We believe that the overcorrection could impact the true meaning of comparisons made with a standard; this was also recently expressed by O’Connell and colleagues [26]. Even so, we agree that these are important factors that have a major impact on frailty levels. We are currently working on constructing a social vulnerability index to understand the impact of these variables on the health of the Canadian ageing population [27].

To our knowledge, there are two other FIs published using the CLSA data. However, none of these used the pooled data, and many of the items included were not associated with age, a main criterion for constructing an FI [28,29]. The FI previously constructed in the tracking cohort reported similar mean and median values; however, it reported higher maximum values (0.67), an effect possibly attributed to some of the included deficits [29]. Regarding the other FI previously constructed using the comprehensive data, the FI mean was of 0.1, with a maximum of 0.53, similar to our data. In addition, research regarding frailty in Canadian older adults has also been published in other population-based projects, with similar results [30].

This CLSA FI was constructed by the group who originally developed this methodology. Even though the FIs presented here were based on slightly, and intentionally, different criteria, our sensitivity analyses showed that the modifications we used for the criteria did not impact on the characteristics of the FI. Population-based ageing datasets are available all over the world, allowing the possibility of having norms for countries from all continents.

Limitations

Our normative values were created using only Canadian data and excluding some populations, such as people living in long-term care facilities and those with cognitive impairment. It would be expected that the frailty levels of Canadians 45–85 would be higher if these people were included in our estimates. For instance, a previous study that included people living in long-term care facilities showed that 24% have FI scores higher than 0.2 [10]. Similarly, a meta-analysis reported that 31.9% of people with Alzheimer’s disease is frail [31]. Prevalence estimates could have also been slightly different if other items were used to construct the FI. Even so, we have shown in multiple studies that the main characteristics of the FI are similar even if different items are used to construct it, providing that standard procedures are followed [32]. Moreover, demographic projections show that the proportion of individuals 85 and over is growing fast [1]. Not having these individuals included in CLSA is clearly a limitation of our study. Finally, it is important to stress that applying a 52-item questionnaire certainly is burdensome and may take some time to complete. Future studies should investigate the feasibility and utility of the tool.

Conclusion

Frailty is a condition that closely reflects the overall health status of an individual and FI levels can be estimated in both middle-aged and older adults. In addition, the FI allows to observe the spread and variability of both the ageing and frailty phenomena. The new standardized frailty tool and the population-based normative frailty values developed in this study could benefit ageing research and clinical care in Canada. Finally, our results raise intriguing possibilities about potential application at the clinical level. Presently, this fact is motivating additional inquiry by our group.

Declarations of Conflicts of Interest

M.K.A. reports grant funding from Sanofi Pasteur, GSK and Pfizer. K.R. is the President and a Chief Science Officer of DGI Clinical, which has contracts with pharma on individualised outcome measurement. In July 2015, he gave a lecture at the Alzheimer Association International Conference in a symposium sponsored by Otsuka and Lundbeck. At that time, he presented at an Advisory Board meeting for Nutricia. In 2017, he attended an advisory board meeting for Lundbeck. He is a member of the Research Executive Committee of the Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration in Aging, which is funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, with additional funding from the Alzheimer Society of Canada and several other charities, as well as from Pfizer Canada and Sanofi Canada. He receives career support from the Dalhousie Medical Research Foundation as the Kathryn Allen Weldon Professor of Alzheimer Research and research support from the Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation, the Capital Health Research Fund and the Fountain Family Innovation Fund of the Nova Scotia Health Authority Foundation.

Declaration of Sources of Funding

This work was supported a grant from the Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation: establishment grant MED-EST-2017-1241, PI Olga Theou. The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article.

Acknowledgements

This research was made possible using the data/biospecimens collected by the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA). Funding for the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA) is provided by the Government of Canada through the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) under grant reference: LSA 94473 and the Canada Foundation for Innovation. This research has been conducted using the CLSA dataset, Baseline Tracking Dataset version 3.3 and the Baseline Comprehensive Dataset version 3.2, under Application Number 160610. The CLSA is led by Drs Parminder Raina, Christina Wolfson and Susan Kirkland.

Comments