-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Kennedy M Blevins, Nicole D Fields, Sarah D Pressman, Christy L Erving, Zachary T Martin, Reneé H Moore, Raphiel J Murden, Rachel Parker, Shivika Udaipuria, Bianca Booker, LaKeia Culler, Viola Vaccarino, Arshed Quyyumi, Tené T Lewis, Superwoman schema and arterial stiffness in Black American women: assessing the role of environmental mastery, Annals of Behavioral Medicine, Volume 59, Issue 1, 2025, kaaf035, https://doi.org/10.1093/abm/kaaf035

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Lay Summary

Black women who highly identified as “Superwomen” or felt the need to be strong, invulnerable, and self-sacrificing had stiffer arteries when they felt like they had less mastery or control over their environments.

Background

Emerging evidence suggests that the Superwoman Schema (SWS)—the sociocultural representation of Black women as naturally strong, independent, and nurturing—may play an important role in Black women’s cardiovascular health; but findings have been relatively mixed. One interesting possibility is that environmental mastery, a sense of control over one’s environment, may mitigate negative aspects of SWS.

Purpose

We investigated whether mastery moderated the association between SWS and pulse wave velocity (PWV), the gold standard measure of arterial stiffness linked to cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

Methods

Participants were N = 368 early middle-aged (30-45 years old) Black women from the southeastern USA who completed the 35-item Giscombé Superwoman Schema Questionnaire and Ryff’s 14-item environmental mastery scale. Carotid-femoral PWV was assessed using the SphygmoCor device. Linear regression models examined the main and interactive associations of SWS and mastery on PWV, adjusting for age, education, income, body mass index, smoking status, blood pressure, and antihypertensive medication use.

Results

Analyses revealed a significant overall SWS endorsement by mastery interaction [β = −.11, P = .02], such that SWS was positively associated with higher PWV only when mastery was low. Three SWS dimensions drove this association: SWS strength, SWS suppress emotions, and SWS resistance to vulnerability (all P-values < .05) showing similar patterns to the overall SWS interaction with mastery.

Conclusions

In Black women, high endorsement of SWS is associated with greater arterial stiffness when environmental mastery is low. Thus, SWS may be more physiologically taxing when one senses less control over their environment.

Introduction

Black women are 32% more likely to die from cardiovascular disease (CVD) compared to their White counterparts and these disparities are most pronounced in middle age.1,2 While traditional risk factors (eg, blood pressure, body mass index [BMI]) remain important, markers of arterial stiffening are increasingly used to assess incremental, early markers of CVD risk.3–5 Arterial stiffening predicts both cardiovascular incidence and mortality.5–7 It is especially important to assess arterial stiffness among Black women before middle age (middle age being 40-60 years old), as changes in arterial stiffening prior to cardiovascular events often occur earlier in Black individuals compared to White individuals.4 However, these changes do not exist in a vacuum, as psychosocial factors are known to relate to disparities in arterial stiffness,8 although there is limited work exploring these links. Given the disparities in arterial stiffening specifically for middle-aged Black women,9 psychosocial factors unique to Black women’s experiences may be linked with arterial stiffness in this population.

The Superwoman Schema (SWS), a culturally based schema relevant to African American women, offers a sociocultural framework through which to analyze and interpret how Black women’s gendered-racial identity is linked with their disparate health outcomes.10 Historically, enslaved Black women were subjected to heavy labor alongside enslaved Black men, yet were also sexually victimized due to their gender.11 These disparate expectations of Black women (ie, working like a man, but experiencing sexual assault and other mistreatment due to gender) persisted in the decades following slavery, arguably through the Jim Crow/Civil Rights era. Sociological literature has shown that these historical juxtapositions, among other differences, have influenced ongoing societal expectations of Black women, with Black women being expected to maintain gendered social roles expected of all women (eg, caregiving) while also being viewed as dominant (eg, strong, independent).11–14 Settles et al.15 highlight these differences, finding that while both Black Women and White women expressed caretaking as an essential component of womanhood only Black women expressed strength as a necessary trait of womanhood. Together, these findings suggest the experience of the Superwoman role exist at the intersection of Black women’s race (ie, being Black) and gender (ie, being women).

To assess the gendered-racial role of Black women using a psychological lens, Woods-Giscombé16 identified 5 dimensions that make up the Superwoman role from Black American women’s narratives: (1) an obligation to present an image of strength (SWS strength; characterized by being expected and perceived to be “the strong one” for their children, family, and friends at home, work, and life more generally); (2) an obligation to suppress emotions (SWS suppress emotions; characterized by difficulty expressing emotions and reluctance to display emotions publicly); (3) resistance to vulnerability and dependence (SWS resistance to vulnerability; characterized by not knowing how to accept help or trust others and needing to be in control or take the lead); (4) motivation to succeed despite limited resources (SWS motivation to succeed; characterized by ambition to be the best even if they did not have everything needed to do so, at times due to pressure from others and even at the expense of one’s health); and (5) obligation to help others for others (SWS obligation to help others; characterized by a felt responsibility to make sure other’s needs were met, having multiple roles and responsibilities, and difficulty saying no). These characteristics are theorized to foster perceived benefits of self-, family-, and community-preservation.10 Though seemingly positive, SWS perpetuates the embodiment of hyper independence, determination for success despite limited resources, and presentation of strength, even if one does not feel strong. Consequently, Black women who more strongly endorse the Superwoman role may suffer health costs.

Although the majority of emerging work on SWS has focused on mental health, with greater SWS being linked with more depression and anxiety, greater emotional suppression, and lower self-esteem,17 there is reason to believe that SWS would be connected to arterial stiffness based on a few studies that have cardiovascular health-relevance.10,18–21 For example, greater endorsement of all SWS dimensions has been linked with worse sleep quality and lower self-reported physical activity.10 Additionally, a recent study by Martin et al.19 found that greater endorsement of 2 SWS subdimensions (SWS motivation to succeed and SWS resistance to vulnerability) was linked with worse brachial artery flow-mediated dilation—a measure of vascular function—in a small sample of 21 Black women. Further, in a cohort of 208 Black women, Perez et al.21 found SWS associations between greater SWS strength and SWS obligation to help others with increased hypertension, while SWS motivation to succeed was linked lower odds of hypertension; however, this study did not assess overall SWS. Finally, another analysis of this same cohort of 208 Black women led by Allen and colleagues18 found some associations between SWS subscales and allostatic load in the context of discrimination, but findings were mixed.

To date, however, the majority of the existing work on SWS and physical health has focused on the negative impact of SWS on health outcomes. To our knowledge no studies have examined the extent to which individual differences in psychosocial resource factors might buffer the association between SWS and physical health outcomes. This is important because psychosocial resources could ultimately be leveraged to inform culturally tailored interventions that might prove critical for protecting cardiovascular health in Black women high in SWS. The current analysis is designed to examine the role that environmental mastery, a psychosocial resource, might play in the SWS-arterial stiffness link.

Environmental mastery is an individual’s appraisal of their ability to effectively manage and control their life and environment,22 which has been linked with better cardiovascular health.23,24 Environmental mastery may be key for Black women in the context of SWS because the felt need to be strong and invulnerable, among other SWS characteristics, emerged in the context of Black women’s historical oppression and powerlessness (eg, slavery and subsequent subjugation due to race and gender).14,25 In other words, situations in which the ability to manage and/or control the external environment was low or nonexistent. Thus, when environmental mastery is low, SWS may operate as expected, with Black women potentially suffering the negative health costs of trying to maintain the Superwoman role in a low-resource context. However, in the context of high environmental mastery, Black women may feel they are able to match the demands of the Superwoman role (eg, expectations to be strong, care for others, etc.) to their ability (ie, the perception that they have high control over their ability to sufficiently meet the expectations of the Superwoman role). This conceptualization is similar to that proposed in the study of John Henryism, which argued that hard-driving, high-effort coping was adaptive with respect to cardiovascular health among Black men in the context of high resources, but maladaptive in the context of low resources.26 However, in the John Henryism literature “resources” have been primarily defined as socioeconomic in nature. Environmental mastery, on the other hand, refers to the individual’s perception about the overall controllability of their external world, not necessarily limited to their economic circumstances.

The current study was designed to examine associations among SWS, environmental mastery, and arterial stiffness (assessed via pulse wave velocity [PWV]) in a cohort of over 400 early middle-aged Black women (30-45 years old). A prior analysis of this cohort by Martin and colleagues,20 found that SWS was associated with higher central systolic blood pressure and augmentation index, but not aortic PWV. However, this analysis only examined the primary association between SWS and PWV, without accounting for environmental mastery as an important psychosocial resource that might moderate any potential associations. Nevertheless, aortic PWV is the gold standard measurement of arterial stiffness.6,7 PWV has also been differentially associated with psychosocial resources (albeit not mastery) in Black individuals when compared to White individuals, whereby inadequate emotional support was linked with worse PWV for Black but not White older adults.8 Therefore, we extended Martin et al.’s20 findings by testing the hypothesis that environmental mastery would temper the link between SWS and PWV. We also examined the dimensions of SWS in secondary analyses to understand which aspects of SWS might be protective versus deleterious.

Methods

Participants

Potential participants for the Mechanisms Underlying Stress and Emotions (MUSE) in African American Women’s health study were identified via National Opinion Research Center services via residential and voter registration lists and were sent a flier introducing the study followed by a telephone call to screen for eligibility.27 Inclusion criteria included identifying as a Black woman, being 30-45 years of age, and being premenopausal with at least one ovary. Individuals were excluded if they had previous clinical cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or chronic illnesses known to influence atherosclerosis (eg, HIV/AIDS, autoimmune diseases); were pregnant or lactating; were currently being treated for psychiatric disorders, illicit drug use, alcohol abuse; or were overnight shift workers (due to the known impact on cardiovascular health).28 A total of 422 respondents completed the 3-h in-person interview and physical assessment. Interviews were conducted in English by interviewers who identified as Black women. All procedures were approved by an Institutional Review Board, and all participants provided written informed consent. Of the 422 participants in the study, N = 368 had PWV data, as some participants had a thigh circumference that exceeded the size of the thigh cuff used to measure PWV. Women with and without data on PWV significantly differed in terms of BMI (M = 31.21, SD = 7.06 for those with PWV data versus M = 43.28, SD = 8.84 for those without PWV data; P = .04); clinic measurements of systolic blood pressure (M = 118.51, SD = 14.03 for those with PWV data versus M = 122.50, SD = 17.66 for those without PWV data; P = .01); and household size (M = 3.47, SD = 1.65 for those with PWV data versus M = 4.26, SD = 2.50 for those without PWV data; P = .003) but did not differ on any of the main study variables or other covariates. The analytic sample of the current study consisted of those women who had observed PWV data.

Measures

Superwoman schema

The 35-item Giscombé Superwoman Schema Questionnaire (G-SWS-Q) was administered to assess the Superwoman Schema role in African American women.10 The scale measured 5 dimensions of the Superwoman Schema: (1) SWS strength (eg, “The struggles of my ancestors require me to be strong”; α = .81), (2) SWS suppress emotions (eg, “My tears are a sign of weakness”; α = .85), (3) SWS resistance to vulnerability (eg, “It’s hard for me to accept help from others”; α = .86), (4) SWS motivation to succeed (eg, “I accomplish my goals with limited resources”; α = .74), (5) SWS obligation to help others (eg, “I take on roles and responsibilities when I am already overwhelmed”; α = .88). All items of the G-SWS-Q were statements which were rated 0 (this is not true for me), 1 (this is true for me rarely), 2 (this is true for me sometimes), or 3 (this is true for me all the time). Responses were summed across items resulting in a summary score for the overall 35-item SWS scale (α = .93). The overall SWS and each SWS dimension were then averaged by the number of items in the overall scale and each dimension, respectively. Higher scores indicate greater endorsement of SWS or each SWS dimension.

Environmental mastery

The environmental mastery subscale of the Psychological Well-being Scale assessed self-rated environmental mastery.22,29 Items such as “I am quite good at managing the many responsibilities of my daily life” and “I often feel overwhelmed by my responsibilities” (reversed) were rated on a 6-point scale (0 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Negatively worded items were re-coded so that higher scores reflected having a sense of mastery and competence in managing the environment; having control of a complex array of external activities; effectively using surrounding opportunities; and choosing or creating contexts suitable to one’s personal needs and values. Items were summed and then averaged by the total number items in the scale with higher scores indicating higher mastery (α = .86).

Pulse wave velocity

Pulse wave velocity was used to measure arterial stiffness noninvasively via the SphygmoCor XCEL PWV system in line with best practices for quantifying arterial stiffness (AtCore). Prior to measurement, participants rested supine for approximately 15 min. All measurements were completed on the right side of the body with femoral artery pulsations detected via thigh cuff and simultaneous common carotid artery pulsations detected via applanation tonometry. Pulse wave velocity was calculated by the SphygmoCor XCEL unit from the distance measurements from the common carotid artery pulsation to the suprasternal notch; suprasternal notch to the top of a blood pressure cuff placed on the upper thigh; and the palpated common femoral artery pulsation to the top of the thigh cuff. Each participant’s PWV measurement was completed once, unless repeat measurements were necessary to meet quality control standards.

Covariates

Covariates were selected based on their established association with cardiovascular disease outcomes. Sociodemographic covariates were self-reported and included age, education in years, and household income (<$35 000; $35 000-$49 999; $50 000-$74 999; and >$75 000) and size. Clinical covariates included BMI (kg/m2), clinic systolic and diastolic blood pressure (mmHg), smoking status (yes/no), and antihypertension use (yes/no). BMI was calculated as weight/height and was measured by the study team and modeled as a continuous variable. Blood pressure was collected during 2 seated clinical sessions by the study team and averaged to get an overall clinic blood pressure measure. Smoking status and antihypertension use were self-reported.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using SPSS Version 29. Descriptive statistics were conducted to characterize the study sample. Bivariate associations among SWS, SWS dimensions, mastery, and PWV were examined using Pearson’s correlation coefficients with pairwise deletion. All psychosocial variables were approximately normally distributed, with the exception of the SWS strength dimension which was left skewed. All main predictor variables were centered at the mean to correct for multicollinearity. Linear regression analyses were conducted to assess the main effect of SWS and interaction between SWS and environmental mastery on PWV. Model 1 adjusted for age, followed by SWS, environmental mastery, and the SWS by environmental mastery interaction term. Model 2 added covariate terms for education in years, household income and size, BMI, systolic, and diastolic blood pressure, smoking status, and antihypertension use. Simple slopes for probing the interaction between SWS and environmental mastery were obtained using the Johnson Neyman technique via PROCESS for SPSS.30 The fully adjusted Model 2 was repeated in exploratory analyses, with each dimension of SWS modeled separately.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. Participants were early middle-aged (M = 37.74 years, SD = 4.22) and socioeconomically diverse, with education ranging from 8-20 years and incomes ranging from <$35k to >$75k. Participants had high BMI (M = 32.76 kg/m2, SD = 8.35), with the majority being nonsmoking (n = 329) and not using antihypertensive mediation (n = 315).

| Variable . | M (SD) . | Observed range . | n (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 37.74 (4.22) | 30.10-46.67 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.21 (7.06) | 17.16-57.43 | |

| Clinic systolic BP (mmHg) | 118.50 (14.03) | 80.00-166.50 | |

| Clinic diastolic BP (mmHg) | 80.01 (11.54) | 55.00-123.00 | |

| Household size | 3.47 (1.65) | 1.00-10.00 | |

| Current smoking | |||

| No | 329 (89.4) | ||

| Antihypertensive use | |||

| No | 315 (85.6) | ||

| Education (years) | |||

| 8 | 1 (.3) | ||

| 9 | 3 (.3) | ||

| 10 | 3 (.8) | ||

| 11 | 6 (1.6) | ||

| 12 | 52 (14.1) | ||

| 13 | 24 (6.5) | ||

| 14 | 82 (22.3) | ||

| 15 | 14 (3.8) | ||

| 16 | 76 (20.7) | ||

| 17 | 10 (2.7) | ||

| 18 | 63 (17.1) | ||

| 19 | 8 (2.2) | ||

| 20 | 22 (6.0) | ||

| Income (USD) | |||

| <35 000k | 87 (23.6) | ||

| 35 000-49 999k | 76 (20.7) | ||

| 50 000-74 999k | 86 (23.4) | ||

| >75k | 110 (29.9) | ||

| Refused | 2 (0.5) | ||

| Don’t know | 5 (1.4) |

| Variable . | M (SD) . | Observed range . | n (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 37.74 (4.22) | 30.10-46.67 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.21 (7.06) | 17.16-57.43 | |

| Clinic systolic BP (mmHg) | 118.50 (14.03) | 80.00-166.50 | |

| Clinic diastolic BP (mmHg) | 80.01 (11.54) | 55.00-123.00 | |

| Household size | 3.47 (1.65) | 1.00-10.00 | |

| Current smoking | |||

| No | 329 (89.4) | ||

| Antihypertensive use | |||

| No | 315 (85.6) | ||

| Education (years) | |||

| 8 | 1 (.3) | ||

| 9 | 3 (.3) | ||

| 10 | 3 (.8) | ||

| 11 | 6 (1.6) | ||

| 12 | 52 (14.1) | ||

| 13 | 24 (6.5) | ||

| 14 | 82 (22.3) | ||

| 15 | 14 (3.8) | ||

| 16 | 76 (20.7) | ||

| 17 | 10 (2.7) | ||

| 18 | 63 (17.1) | ||

| 19 | 8 (2.2) | ||

| 20 | 22 (6.0) | ||

| Income (USD) | |||

| <35 000k | 87 (23.6) | ||

| 35 000-49 999k | 76 (20.7) | ||

| 50 000-74 999k | 86 (23.4) | ||

| >75k | 110 (29.9) | ||

| Refused | 2 (0.5) | ||

| Don’t know | 5 (1.4) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; USD, United States Dollars; Percentages represent percentages from sample n of 368 women with complete PWV data; Smoking Status missing 1 case; Education missing 6 cases; Income missing 2 cases.

| Variable . | M (SD) . | Observed range . | n (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 37.74 (4.22) | 30.10-46.67 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.21 (7.06) | 17.16-57.43 | |

| Clinic systolic BP (mmHg) | 118.50 (14.03) | 80.00-166.50 | |

| Clinic diastolic BP (mmHg) | 80.01 (11.54) | 55.00-123.00 | |

| Household size | 3.47 (1.65) | 1.00-10.00 | |

| Current smoking | |||

| No | 329 (89.4) | ||

| Antihypertensive use | |||

| No | 315 (85.6) | ||

| Education (years) | |||

| 8 | 1 (.3) | ||

| 9 | 3 (.3) | ||

| 10 | 3 (.8) | ||

| 11 | 6 (1.6) | ||

| 12 | 52 (14.1) | ||

| 13 | 24 (6.5) | ||

| 14 | 82 (22.3) | ||

| 15 | 14 (3.8) | ||

| 16 | 76 (20.7) | ||

| 17 | 10 (2.7) | ||

| 18 | 63 (17.1) | ||

| 19 | 8 (2.2) | ||

| 20 | 22 (6.0) | ||

| Income (USD) | |||

| <35 000k | 87 (23.6) | ||

| 35 000-49 999k | 76 (20.7) | ||

| 50 000-74 999k | 86 (23.4) | ||

| >75k | 110 (29.9) | ||

| Refused | 2 (0.5) | ||

| Don’t know | 5 (1.4) |

| Variable . | M (SD) . | Observed range . | n (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 37.74 (4.22) | 30.10-46.67 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.21 (7.06) | 17.16-57.43 | |

| Clinic systolic BP (mmHg) | 118.50 (14.03) | 80.00-166.50 | |

| Clinic diastolic BP (mmHg) | 80.01 (11.54) | 55.00-123.00 | |

| Household size | 3.47 (1.65) | 1.00-10.00 | |

| Current smoking | |||

| No | 329 (89.4) | ||

| Antihypertensive use | |||

| No | 315 (85.6) | ||

| Education (years) | |||

| 8 | 1 (.3) | ||

| 9 | 3 (.3) | ||

| 10 | 3 (.8) | ||

| 11 | 6 (1.6) | ||

| 12 | 52 (14.1) | ||

| 13 | 24 (6.5) | ||

| 14 | 82 (22.3) | ||

| 15 | 14 (3.8) | ||

| 16 | 76 (20.7) | ||

| 17 | 10 (2.7) | ||

| 18 | 63 (17.1) | ||

| 19 | 8 (2.2) | ||

| 20 | 22 (6.0) | ||

| Income (USD) | |||

| <35 000k | 87 (23.6) | ||

| 35 000-49 999k | 76 (20.7) | ||

| 50 000-74 999k | 86 (23.4) | ||

| >75k | 110 (29.9) | ||

| Refused | 2 (0.5) | ||

| Don’t know | 5 (1.4) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; USD, United States Dollars; Percentages represent percentages from sample n of 368 women with complete PWV data; Smoking Status missing 1 case; Education missing 6 cases; Income missing 2 cases.

Correlations, means, and standard deviations for each of the primary study variables are listed in Table 2. Overall SWS was correlated with lower mastery (r = −.39, P < .001). Only SWS motivation to succeed was significantly weakly correlated with PWV (r = .12, P = .02).

| Means, standard deviations, and correlations with confidence intervals of primary study variables.

| Variable . | M (SD) . | Range . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SWS | 1.92 (0.50) | 0-2.86 | |||||||

| 2. SWS Strength | 2.24 (0.63) | 0.57-5.00 | .72** [.67, .77] | ||||||

| 3. SWS Suppress | 1.65 (0.68) | 0-3.00 | .77** [.72, .81] | .46** [.38, .54] | |||||

| 4. SWS Vulnerability | 1.92 (0.69) | 0-3.00 | .83** [.79, .86] | .44** [.36, .52] | .65** [.59, .70] | ||||

| 5. SWS Motivation | 2.25 (0.51) | 0-3.00 | .71** [.65, .75] | .59** [.51, .65] | .35** [.25, .44] | .50** [.42, .57] | |||

| 6. SWS Help | 1.70 (0.68) | 0-3.00 | .81** [.77, .84] | .44** [.36, .52] | .45** [.36, .53] | .55** [.47, .61] | .49** [.41, .57] | ||

| 7. Mastery | 3.56 (0.80) | 0-3.00 | −.38** [−.47, −.29] | −.13* [−.23, −.03] | −.35** [−.44, −.26] | −.32** [−.41, −.23] | −.11* [−.21, −.01] | −.43** [−.51, −.34] | |

| 8. PWV | 6.21 (1.53) | 3.20-16.60 | .09 [−.01, .19] | .03 [−.07, .14] | .06 [−.04, .16] | .09 [−.01, .19] | .12* [.02, .22] | .05 [−.06, .15] | −.05 [−.15, .05] |

| Variable . | M (SD) . | Range . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SWS | 1.92 (0.50) | 0-2.86 | |||||||

| 2. SWS Strength | 2.24 (0.63) | 0.57-5.00 | .72** [.67, .77] | ||||||

| 3. SWS Suppress | 1.65 (0.68) | 0-3.00 | .77** [.72, .81] | .46** [.38, .54] | |||||

| 4. SWS Vulnerability | 1.92 (0.69) | 0-3.00 | .83** [.79, .86] | .44** [.36, .52] | .65** [.59, .70] | ||||

| 5. SWS Motivation | 2.25 (0.51) | 0-3.00 | .71** [.65, .75] | .59** [.51, .65] | .35** [.25, .44] | .50** [.42, .57] | |||

| 6. SWS Help | 1.70 (0.68) | 0-3.00 | .81** [.77, .84] | .44** [.36, .52] | .45** [.36, .53] | .55** [.47, .61] | .49** [.41, .57] | ||

| 7. Mastery | 3.56 (0.80) | 0-3.00 | −.38** [−.47, −.29] | −.13* [−.23, −.03] | −.35** [−.44, −.26] | −.32** [−.41, −.23] | −.11* [−.21, −.01] | −.43** [−.51, −.34] | |

| 8. PWV | 6.21 (1.53) | 3.20-16.60 | .09 [−.01, .19] | .03 [−.07, .14] | .06 [−.04, .16] | .09 [−.01, .19] | .12* [.02, .22] | .05 [−.06, .15] | −.05 [−.15, .05] |

M and SD are used to represent mean and standard deviation, respectively. Values in square brackets indicate the 95% confidence interval for each correlation. SWS = Overall Superwoman Schema; SWS Strength = obligation to present an image of strength; SWS Suppress = obligation to suppress emotions; SWS Vulnerability = resistance to vulnerability and dependence; SWS Motivation = motivation to succeed despite limited resources; SWS Help = obligation to help others for others,

*P < .05.

**P < .01.

| Means, standard deviations, and correlations with confidence intervals of primary study variables.

| Variable . | M (SD) . | Range . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SWS | 1.92 (0.50) | 0-2.86 | |||||||

| 2. SWS Strength | 2.24 (0.63) | 0.57-5.00 | .72** [.67, .77] | ||||||

| 3. SWS Suppress | 1.65 (0.68) | 0-3.00 | .77** [.72, .81] | .46** [.38, .54] | |||||

| 4. SWS Vulnerability | 1.92 (0.69) | 0-3.00 | .83** [.79, .86] | .44** [.36, .52] | .65** [.59, .70] | ||||

| 5. SWS Motivation | 2.25 (0.51) | 0-3.00 | .71** [.65, .75] | .59** [.51, .65] | .35** [.25, .44] | .50** [.42, .57] | |||

| 6. SWS Help | 1.70 (0.68) | 0-3.00 | .81** [.77, .84] | .44** [.36, .52] | .45** [.36, .53] | .55** [.47, .61] | .49** [.41, .57] | ||

| 7. Mastery | 3.56 (0.80) | 0-3.00 | −.38** [−.47, −.29] | −.13* [−.23, −.03] | −.35** [−.44, −.26] | −.32** [−.41, −.23] | −.11* [−.21, −.01] | −.43** [−.51, −.34] | |

| 8. PWV | 6.21 (1.53) | 3.20-16.60 | .09 [−.01, .19] | .03 [−.07, .14] | .06 [−.04, .16] | .09 [−.01, .19] | .12* [.02, .22] | .05 [−.06, .15] | −.05 [−.15, .05] |

| Variable . | M (SD) . | Range . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | 5 . | 6 . | 7 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SWS | 1.92 (0.50) | 0-2.86 | |||||||

| 2. SWS Strength | 2.24 (0.63) | 0.57-5.00 | .72** [.67, .77] | ||||||

| 3. SWS Suppress | 1.65 (0.68) | 0-3.00 | .77** [.72, .81] | .46** [.38, .54] | |||||

| 4. SWS Vulnerability | 1.92 (0.69) | 0-3.00 | .83** [.79, .86] | .44** [.36, .52] | .65** [.59, .70] | ||||

| 5. SWS Motivation | 2.25 (0.51) | 0-3.00 | .71** [.65, .75] | .59** [.51, .65] | .35** [.25, .44] | .50** [.42, .57] | |||

| 6. SWS Help | 1.70 (0.68) | 0-3.00 | .81** [.77, .84] | .44** [.36, .52] | .45** [.36, .53] | .55** [.47, .61] | .49** [.41, .57] | ||

| 7. Mastery | 3.56 (0.80) | 0-3.00 | −.38** [−.47, −.29] | −.13* [−.23, −.03] | −.35** [−.44, −.26] | −.32** [−.41, −.23] | −.11* [−.21, −.01] | −.43** [−.51, −.34] | |

| 8. PWV | 6.21 (1.53) | 3.20-16.60 | .09 [−.01, .19] | .03 [−.07, .14] | .06 [−.04, .16] | .09 [−.01, .19] | .12* [.02, .22] | .05 [−.06, .15] | −.05 [−.15, .05] |

M and SD are used to represent mean and standard deviation, respectively. Values in square brackets indicate the 95% confidence interval for each correlation. SWS = Overall Superwoman Schema; SWS Strength = obligation to present an image of strength; SWS Suppress = obligation to suppress emotions; SWS Vulnerability = resistance to vulnerability and dependence; SWS Motivation = motivation to succeed despite limited resources; SWS Help = obligation to help others for others,

*P < .05.

**P < .01.

Test of main effects and moderation

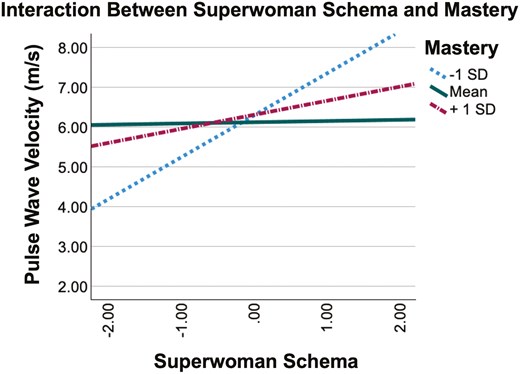

There were no significant main associations between overall SWS or environmental mastery and PWV in the age-adjusted or fully adjusted models (Table 3). However, there was an overall SWS by environmental mastery interaction on PWV that was P = .07 in the age-adjusted model and P = .02 in the fully adjusted model (β = −.11; Table 3). Figure 1 demonstrates this association and reveals that overall SWS was significantly associated with PWV only when environmental mastery was low, β = .61, SE = 0.26, t = 2.39, P = .02. There was not a significant effect of SWS on PWV at the sample average of environmental mastery, β = .30, SE = 0.17, t = 1.73, P = .08, or high environmental mastery, β = −.01, SE = 0.22, t = −0.05, P = .96.

| Results of hierarchical linear regressions predicting PWV from Superwoman Schema and Environmental Mastery.

| Variable . | Age-adjusted . | Fully adjusted . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β* . | β (SE) . | CI (LL, UL) . | P . | Partial correlation . | β* . | β (SE) . | CI (LL, UL) . | P . | Partial correlation . | |

| SWS | .09 | .28 (.17) | [−.05,.62] | .10 | .09 | .08 | .23 (.15) | [−.07,.53] | .133 | .07 |

| Mastery | −.002 | −.005 (.11) | [−.22,.21] | .97 | −.06 | −.03 | −.05 (.10) | [−.14,.24] | .588 | −.023 |

| SWS × Mastery | −.10 | −.36 (.20) | [−.76,.03] | .07 | −.09 | −.11 | −.41 (.18) | [−.75, −.06] | .021 | −.117 |

| Variable . | Age-adjusted . | Fully adjusted . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β* . | β (SE) . | CI (LL, UL) . | P . | Partial correlation . | β* . | β (SE) . | CI (LL, UL) . | P . | Partial correlation . | |

| SWS | .09 | .28 (.17) | [−.05,.62] | .10 | .09 | .08 | .23 (.15) | [−.07,.53] | .133 | .07 |

| Mastery | −.002 | −.005 (.11) | [−.22,.21] | .97 | −.06 | −.03 | −.05 (.10) | [−.14,.24] | .588 | −.023 |

| SWS × Mastery | −.10 | −.36 (.20) | [−.76,.03] | .07 | −.09 | −.11 | −.41 (.18) | [−.75, −.06] | .021 | −.117 |

SWS = Overall Superwoman Schema. β* = Standardized Beta. β = Unstandardized Beta. Values in square brackets indicate the 95% confidence interval for each unstandardized beta. Abbreviations: LL, lower limit; UL, upper limit. Significant effects denoted in bold. SWS × Mastery = Superwoman Schema and environmental mastery Interaction.

| Results of hierarchical linear regressions predicting PWV from Superwoman Schema and Environmental Mastery.

| Variable . | Age-adjusted . | Fully adjusted . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β* . | β (SE) . | CI (LL, UL) . | P . | Partial correlation . | β* . | β (SE) . | CI (LL, UL) . | P . | Partial correlation . | |

| SWS | .09 | .28 (.17) | [−.05,.62] | .10 | .09 | .08 | .23 (.15) | [−.07,.53] | .133 | .07 |

| Mastery | −.002 | −.005 (.11) | [−.22,.21] | .97 | −.06 | −.03 | −.05 (.10) | [−.14,.24] | .588 | −.023 |

| SWS × Mastery | −.10 | −.36 (.20) | [−.76,.03] | .07 | −.09 | −.11 | −.41 (.18) | [−.75, −.06] | .021 | −.117 |

| Variable . | Age-adjusted . | Fully adjusted . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β* . | β (SE) . | CI (LL, UL) . | P . | Partial correlation . | β* . | β (SE) . | CI (LL, UL) . | P . | Partial correlation . | |

| SWS | .09 | .28 (.17) | [−.05,.62] | .10 | .09 | .08 | .23 (.15) | [−.07,.53] | .133 | .07 |

| Mastery | −.002 | −.005 (.11) | [−.22,.21] | .97 | −.06 | −.03 | −.05 (.10) | [−.14,.24] | .588 | −.023 |

| SWS × Mastery | −.10 | −.36 (.20) | [−.76,.03] | .07 | −.09 | −.11 | −.41 (.18) | [−.75, −.06] | .021 | −.117 |

SWS = Overall Superwoman Schema. β* = Standardized Beta. β = Unstandardized Beta. Values in square brackets indicate the 95% confidence interval for each unstandardized beta. Abbreviations: LL, lower limit; UL, upper limit. Significant effects denoted in bold. SWS × Mastery = Superwoman Schema and environmental mastery Interaction.

The association between Superwoman Schema (SWS) and PWV is moderated by environmental mastery. SWS units represent standard deviations from the average of SWS scores (ie, SWS units are centered at the mean). Plot shows the association between SWS centered at the mean and PWV at conditional values of the moderator (ie, one standard deviation above and below mean centered values of environmental mastery).

Exploratory analyses with SWS dimensions

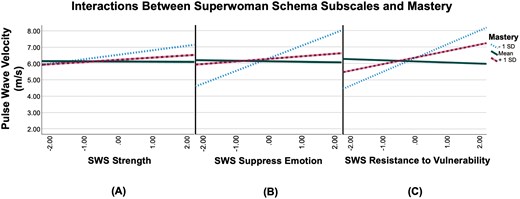

Interestingly, the dimension SWS motivation to succeed was not associated with PWV in age-adjusted models but was significant in the fully adjusted model (Table 4). There was no main effect of SWS obligation to help others and no significant interaction between SWS motivation to succeed or SWS obligation to help others and environmental mastery (Table 4). Three SWS dimensions drove the interaction between SWS by environmental mastery on PWV, showing similar patterns to the overall scale: SWS strength (β = −.10; Figure 2), SWS suppress emotions (β = −.14; Figure 2), and SWS resistance to vulnerability (β = −.12; Figure 2).

| Exploratory analyses examining dimensions of Superwoman Schema with environmental mastery on PWV (m/s).

| Predictor . | Moderator/Interaction . | Standardized Beta . | Unstandardized Beta (SE) . | CI (LL, UL) . | P . | Partial correlation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWS Strength | .05 | .13(.11) | [−.10,.35] | .266 | .044 | |

| Mastery | −.003 | −.006(.09) | [−.18,.17] | .942 | −.023 | |

| SWS Strength × Mastery | −.10 | −.30(.15) | [−.59, −.02] | .039 | −.104 | |

| SWS Suppress | .07 | .14(.11) | [−.08,.37] | .206 | .06 | |

| Mastery | .03 | .05(.10) | [−.21,.16] | .624 | −.023 | |

| SWS Suppress × Mastery | −.14 | −.39(.13) | [−.63, −.10] | .003 | −.153 | |

| SWS Vulnerability | .09 | .19(.11) | [−.03,.40] | .088 | .079 | |

| Mastery | .02 | .04(.09) | [−.14,.23] | .657 | −.023 | |

| SWS Vulnerability × Mastery | −.12 | −.31(.13) | [−.55, −.06] | .014 | −.122 | |

| SWS Motivation | .12 | .35(.14) | [.08,.62] | .012 | .13 | |

| Mastery | −.007 | −.01(.09) | [−.19,.16] | .882 | −.023 | |

| SWS Motivation × Mastery | −.06 | −.22(.17) | [−.56,.11] | .19 | −.06 | |

| SWS Help | −.007 | −.02(.12) | [−.25,.22] | .892 | .000 | |

| Mastery | −.02 | −.04(.10) | [−.24,.17] | .731 | −.023 | |

| SWS Help × Mastery | −.02 | −.06(.13) | [−.33,.20] | .631 | −.031 |

| Predictor . | Moderator/Interaction . | Standardized Beta . | Unstandardized Beta (SE) . | CI (LL, UL) . | P . | Partial correlation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWS Strength | .05 | .13(.11) | [−.10,.35] | .266 | .044 | |

| Mastery | −.003 | −.006(.09) | [−.18,.17] | .942 | −.023 | |

| SWS Strength × Mastery | −.10 | −.30(.15) | [−.59, −.02] | .039 | −.104 | |

| SWS Suppress | .07 | .14(.11) | [−.08,.37] | .206 | .06 | |

| Mastery | .03 | .05(.10) | [−.21,.16] | .624 | −.023 | |

| SWS Suppress × Mastery | −.14 | −.39(.13) | [−.63, −.10] | .003 | −.153 | |

| SWS Vulnerability | .09 | .19(.11) | [−.03,.40] | .088 | .079 | |

| Mastery | .02 | .04(.09) | [−.14,.23] | .657 | −.023 | |

| SWS Vulnerability × Mastery | −.12 | −.31(.13) | [−.55, −.06] | .014 | −.122 | |

| SWS Motivation | .12 | .35(.14) | [.08,.62] | .012 | .13 | |

| Mastery | −.007 | −.01(.09) | [−.19,.16] | .882 | −.023 | |

| SWS Motivation × Mastery | −.06 | −.22(.17) | [−.56,.11] | .19 | −.06 | |

| SWS Help | −.007 | −.02(.12) | [−.25,.22] | .892 | .000 | |

| Mastery | −.02 | −.04(.10) | [−.24,.17] | .731 | −.023 | |

| SWS Help × Mastery | −.02 | −.06(.13) | [−.33,.20] | .631 | −.031 |

Values in square brackets indicate the 95% confidence interval for each unstandardized beta. Abbreviations: LL, lower limit; UL, upper limit. Significant effects denoted in bold. SWS Strength × Mastery = obligation to present an image of strength and environmental mastery Interaction, SWS Suppress × Mastery = obligation to suppress emotions and environmental mastery Interaction, SWS Vulnerability × Mastery = resistance to vulnerability and dependence and environmental mastery interaction, SWS Motivation × Mastery = motivation to succeed despite limited resources and environmental mastery Interaction, SWS Help × Mastery = obligation to help others for others and environmental mastery interaction.

| Exploratory analyses examining dimensions of Superwoman Schema with environmental mastery on PWV (m/s).

| Predictor . | Moderator/Interaction . | Standardized Beta . | Unstandardized Beta (SE) . | CI (LL, UL) . | P . | Partial correlation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWS Strength | .05 | .13(.11) | [−.10,.35] | .266 | .044 | |

| Mastery | −.003 | −.006(.09) | [−.18,.17] | .942 | −.023 | |

| SWS Strength × Mastery | −.10 | −.30(.15) | [−.59, −.02] | .039 | −.104 | |

| SWS Suppress | .07 | .14(.11) | [−.08,.37] | .206 | .06 | |

| Mastery | .03 | .05(.10) | [−.21,.16] | .624 | −.023 | |

| SWS Suppress × Mastery | −.14 | −.39(.13) | [−.63, −.10] | .003 | −.153 | |

| SWS Vulnerability | .09 | .19(.11) | [−.03,.40] | .088 | .079 | |

| Mastery | .02 | .04(.09) | [−.14,.23] | .657 | −.023 | |

| SWS Vulnerability × Mastery | −.12 | −.31(.13) | [−.55, −.06] | .014 | −.122 | |

| SWS Motivation | .12 | .35(.14) | [.08,.62] | .012 | .13 | |

| Mastery | −.007 | −.01(.09) | [−.19,.16] | .882 | −.023 | |

| SWS Motivation × Mastery | −.06 | −.22(.17) | [−.56,.11] | .19 | −.06 | |

| SWS Help | −.007 | −.02(.12) | [−.25,.22] | .892 | .000 | |

| Mastery | −.02 | −.04(.10) | [−.24,.17] | .731 | −.023 | |

| SWS Help × Mastery | −.02 | −.06(.13) | [−.33,.20] | .631 | −.031 |

| Predictor . | Moderator/Interaction . | Standardized Beta . | Unstandardized Beta (SE) . | CI (LL, UL) . | P . | Partial correlation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWS Strength | .05 | .13(.11) | [−.10,.35] | .266 | .044 | |

| Mastery | −.003 | −.006(.09) | [−.18,.17] | .942 | −.023 | |

| SWS Strength × Mastery | −.10 | −.30(.15) | [−.59, −.02] | .039 | −.104 | |

| SWS Suppress | .07 | .14(.11) | [−.08,.37] | .206 | .06 | |

| Mastery | .03 | .05(.10) | [−.21,.16] | .624 | −.023 | |

| SWS Suppress × Mastery | −.14 | −.39(.13) | [−.63, −.10] | .003 | −.153 | |

| SWS Vulnerability | .09 | .19(.11) | [−.03,.40] | .088 | .079 | |

| Mastery | .02 | .04(.09) | [−.14,.23] | .657 | −.023 | |

| SWS Vulnerability × Mastery | −.12 | −.31(.13) | [−.55, −.06] | .014 | −.122 | |

| SWS Motivation | .12 | .35(.14) | [.08,.62] | .012 | .13 | |

| Mastery | −.007 | −.01(.09) | [−.19,.16] | .882 | −.023 | |

| SWS Motivation × Mastery | −.06 | −.22(.17) | [−.56,.11] | .19 | −.06 | |

| SWS Help | −.007 | −.02(.12) | [−.25,.22] | .892 | .000 | |

| Mastery | −.02 | −.04(.10) | [−.24,.17] | .731 | −.023 | |

| SWS Help × Mastery | −.02 | −.06(.13) | [−.33,.20] | .631 | −.031 |

Values in square brackets indicate the 95% confidence interval for each unstandardized beta. Abbreviations: LL, lower limit; UL, upper limit. Significant effects denoted in bold. SWS Strength × Mastery = obligation to present an image of strength and environmental mastery Interaction, SWS Suppress × Mastery = obligation to suppress emotions and environmental mastery Interaction, SWS Vulnerability × Mastery = resistance to vulnerability and dependence and environmental mastery interaction, SWS Motivation × Mastery = motivation to succeed despite limited resources and environmental mastery Interaction, SWS Help × Mastery = obligation to help others for others and environmental mastery interaction.

(A) The main effect of Superwoman Schema (SWS) obligation to present an image of strength on PWV is moderated by environmental mastery. The plot shows the association between SWS obligation to present an image of strength centered at the mean (measured in standard deviation units) and PWV at conditional values of the moderator (ie, one standard deviation above and below mean centered values of environmental mastery). (B) The main effect of SWS obligation to suppress emotions on PWV is moderated by environmental mastery. The plot shows the association between SWS obligation to suppress emotions centered at the mean (measured in standard deviation units) and PWV at conditional values of environmental mastery. (C) The main effect of SWS resistance to vulnerability and dependence on PWV is moderated by environmental mastery. The plot shows the association between SWS resistance to vulnerability and dependence centered at the mean (measured in standard deviation units) and PWV at conditional values of environmental mastery.

Discussion

The primary goal of this study was to assess whether overall SWS was associated with PWV and whether the potential link between overall SWS and PWV was tempered by levels of environmental mastery in a cohort of early middle-aged (ages 30-45) Black women. While SWS was not linked with PWV alone, there was an interaction between SWS and mastery, such that Black women with greater SWS endorsement had higher PWV, but only when mastery was low. These findings suggest that upholding the Superwoman role when one feels less control over their environment may be deleterious to Black women’s cardiovascular health. This is particularly important as Black women suffer disproportionate cardiovascular outcomes compared to women of other racial/ethnic groups that are not explained by traditional risk factors alone (eg, high blood pressure, diabetes).31,32 Our findings suggest environmental mastery as a potential mutable factor in subclinical cardiovascular disease in Black women.

Although the primary objective of this study was to examine the role of environmental mastery as a potential moderator of the overall SWS and PWV association, we did not observe a main effect of overall SWS on PWV in the current analysis. The lack of an association between SWS and PWV was previously reported in this cohort,20 but associations have been documented between SWS and other markers of cardiovascular health, where overall SWS endorsement in Black women was linked with worse sleep,10 less physical activity,10 higher central systolic blood pressure and augmentation index (in the current cohort),20 and lower brachial artery flow-mediated dilation.19 Still, Kyalwazi et al.33 found no association between SWS and common cardiovascular risk factors of obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, or diabetes—though that sample was small, with only N = 38 Black women. We focused on PWV, given its demonstrated relevance for later clinical outcomes; however, our null main effects could potentially be due to the age and relative health of our cohort, as prior studies observing associations between psychosocial factors and PWV have been in older,8 or chronically ill cohorts.34 However, associations have also been observed between psychosocial resources and PWV in adolescents,35 thus age may not be the only factor underlying our lack of significant association between SWS and PWV.

Nonetheless, when considered in the context of environmental mastery, each standard deviation unit increase in Superwoman role endorsement was linked with a 61 m/s increase in PWV only when mastery was low. Vlachopoulos and colleagues7 found a 1 m/s increase in PWV reflected a 14% increase in cardiovascular events and a 15% increase in cardiovascular mortality. When scaled based on these values, the findings from our study could reflect a 6.5%-7% increase in clinical events for Black women in our sample with low reports of mastery who also endorse the Superwoman Schema. The Superwoman role posits presentation of and obligation to the ideals of being a Superwoman (eg, strong, emotionally contained, invulnerable); however, this identity ideal does not require that one actually be able to meet the demands of the role. Thus, with high mastery, ie, when Black women feel they have control of their environment, those high in SWS may feel they have the resources to meet the demands of the Superwoman role—rather than merely presenting strength or independence out of obligation. Thus, in the context of high environmental mastery, the effort matches the demand, and greater SWS endorsement is not linked with higher (ie, worse) PWV. However, when Black women highly endorse SWS, yet continually attempt to master stressors, even if they are uncontrollable (ie, when mastery is low), cardiovascular health risks may arise. This parallels findings from the broader psychosocial cardiovascular health literature, which has consistently found that compared to controllable stressors, uncontrollable stressors are linked with greater cardiovascular disease risk.36

Given the main finding of an interaction between overall SWS and environmental mastery, we further conducted exploratory examinations of each SWS dimension with environmental mastery on PWV. Three of the 5 SWS dimensions (eg, SWS strength, SWS suppress emotions, and SWS resistance to vulnerability) showed a similar pattern to the overall scale (ie, they were linked with greater PWV only when mastery was low). This suggests that different dimensions of the SWS may be more deleterious to arterial health than others in the context of low environmental mastery.

In parallel to the findings for the overall SWS scale, our findings demonstrate that an obligation to present an image of strength is associated with worse arterial stiffness only among Black women reporting low levels of mastery. Thus, perhaps strength in and of itself is not negative; however, when Black women do not have a sense of mastery or control over their environment (ie, when they potentially feel powerless), it may be linked with adverse health outcomes. This idea coincides with other work showing cultural pressures on Black populations to self-present in specific positive ways, especially in low-control situations. For example, Black individuals report greater levels of social desirability,37 show more positive and less negative expressions to emotional stimuli,38 and underreport negative emotions.39 In the case of the SWS strength dimension, Black women may report an obligation to present this image of strength, even when they do not feel strong (ie, when mastery is low), thus posing a risk to Black women’s health.

Similarly, the SWS dimension obligation to suppress emotions posits an obligation to display or contain emotions in a certain manner, without regard to how one is truly feeling. Obligation to suppress emotions was also one of the dimensions driving the association between overall SWS and PWV when environmental mastery was low. Emotional suppression has generally been linked with poor health both generally40 and in the context of the SWS.10 This is thought to occur because inhibition of emotion requires physiological work.41 Ample evidence has connected this suppression to physiological changes and negative outcomes, such as dysregulated immune function42 and symptoms of psychological distress.43 Emotional suppression is an aspect of emotion regulation; thus, in the context of low environmental mastery, the emotional suppression dimension of SWS may reflect a lower ability to regulate one’s emotions when individuals feel less sense of control.

Finally, SWS resistance to vulnerability was an additional dimension underlying our observed associations among overall SWS, environmental mastery, and greater PWV. Resistance to vulnerability and dependence includes resisting asking for help in an effort to maintain control and others’ perceptions of one’s self.10,16 As with the other SWS constructs, when mastery is high, being a Superwoman may reflect a genuine ability to maintain control and ability to be self-sufficient and independent. Whereas in situations where mastery is low, not displaying vulnerability may be maladaptive for Black women who actually need help navigating or managing their environments.44

Though core to the conceptualization of the overall SWS construct, the SWS dimension obligation to help others for others was not linked with PWV in any of the models (ie, independently or in conjunction with environmental mastery). This dimension of SWS is similar to the concept of Unmitigated Communion, characterized by an excessive concern for others and placing other’s needs before one’s own. Unmitigated Communion is a well-studied health risk factor found primarily in female populations.45 This research area has shown that feeling obligated to focus on caring for others instead of oneself can lead to a host of problems such as depressive symptoms, increased network stress burden, poor adjustment to disease (including heart disease), and poor health behaviors.45 Critically, enacting this type of support has been tied to elevated cardiovascular reactivity in the lab,46 providing a potential pathway to CVD risk. Other research with this cohort has shown that SWS obligation to help others was also linked with reduced sleep duration and quality47 and elevated systolic blood pressure and augmentation index—a measure of arterial function.20 However, these analyses did not consider moderators of the SWS-health link. Though no link was found between SWS obligation to help others with PWV in conjunction with environmental mastery in the current analysis, this may be because the obligation to help others dimension is more social in nature, rather than being tied to control.

Limitations

Data for PWV in our sample were not missing at random, as data from 54 participants in the study could not be collected due to challenges with the thigh cuff of the SphygmoCor PWV system not being able to accommodate larger thighs.48 The group of Black women most likely to be excluded were those with BMIs > 40. However, given the known differences in body composition for Black women compared to women of other racial/ethnic groups—with Black women having greater amounts of both lean and fat tissue in their thighs—the exclusion of Black women with BMIs > 40 is not believed to be solely due to the body size of Black women, but also their body shapes.48 Due to this, those Black women who might arguably be at the most elevated risk (ie, have the highest BMI but differing body compositions to their White counterparts) are missing from this analysis—although this is arguably a limitation of all studies with PWV as the outcome.

Additionally, our findings are based on the experiences of Black women and may not be generalizable to women from other racial/ethnic backgrounds. This is important because while certain aspects of SWS (eg, caregiving) may be consistent with gender roles for women more broadly, irrespective of race/ethnicity, the “strength” component of SWS was developed in the context of Black women’s experiences specifically. The literature on the expectation, socialization and felt need for Black women to be strong spans several decades and has been detailed in fields as diverse as political science,49 theology,50 anthropology,51,52 sociology,13,14 as well as quantitative analyses of Black women’s magazines.53 Thus, while it is possible that individual women from other racial/ethnic backgrounds might endorse high levels on various dimensions of the SWS scale, it is unclear whether those reports would result from cultural socialization and historical expectations or individual-level processes. Furthermore, because the scale has only been validated in Black women, future research embarking on additional validation with women from other racial/ethnic backgrounds may be warranted prior to widespread use (including qualitative feedback and consideration of the historical legacies and societal pressures of the group(s) in question).

In addition to sociocultural considerations, future studies should assess whether the current findings are observed across other indices of cardiovascular disease (eg, high blood pressure, heart rate variability, cardiac events). Additionally, since the current study was cross-sectional future investigations should assess how environmental mastery may change over time, as mastery has been found to be amenable to intervention,54 thus, may be leveraged to improve cardiovascular outcomes for Black women. Specifically, an intervention to increase a sense of control, especially in the context of specific domains relevant to SWS (eg, strength, independence) might be helpful for this group, as previous studies have shown improving a sense of control over one’s environment has led to improvements in mastery.55 Lastly, this study looked at middle-aged Black women; therefore, these results may differ for women who are older or younger. Despite these limitations, the findings from this study provide important evidence for the role of Black women’s gender-racial identity in their cardiovascular health.

Conclusion

Overall, our findings demonstrate that, among Black women, greater Superwoman Schema endorsement is related to increased arterial stiffness only when environmental mastery is low. Our findings highlight the importance of evaluating psychosocial context (eg, Superwoman Schema) and resources (eg, environmental mastery) when considering targets of intervention for mitigating cardiovascular health disparities in Black women.

Author contributions

Kennedy M. Blevins (Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Nicole D. Fields (Formal analysis, Writing—review & editing), Sarah D. Pressman (Writing—review & editing), Christy L. Erving (Writing—review & editing), Zachary T. Martin (Writing—review & editing), Reneé Moore (Data curation, Writing—review & editing), Raphiel Murden (Data curation, Writing—review & editing), Rachel Parker (Data curation, Writing—review & editing), Shivika Udaipuria (Data curation), Bianca Booker (Project administration, Writing—review & editing), LaKeia Culler (Project administration, Writing—review & editing), Viola Vaccarino (Writing—review & editing), Arshed Quyyumi (Writing—review & editing), and Tené T. Lewis (Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision; Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing)

Funding

The MUSE study is funded by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, grants R01 HL130471 and R01 HL158141 to T.T. Lewis. T.T. Lewis received additional funding from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, grant K24 HL163696. Z. Martin and N. Fields were supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute grant T32 HL130025. The funders were not involved in the conceptualization of the research, the study design or conduct, nor any aspect of data analysis, interpretation, writing, or decision to submit for publication.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Transparency statements

Study Registration. This study is not a clinical trial and was not subject to formal registration requirements. Analytic Plan Registration. The analysis plan for this study was not formally preregistered. Data Availability. Data from this study are not publicly available. De-identified data from this project are subject to institutional IRB allowability/participant consent and can be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author. Analytic Code Availability. Analytic code used to generate the results presented in this manuscript are not publicly available but can be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author. Materials Availability. Materials used to conduct the study are not publicly available.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the study’s Institutional Review Board and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. All participants provided written informed consent.